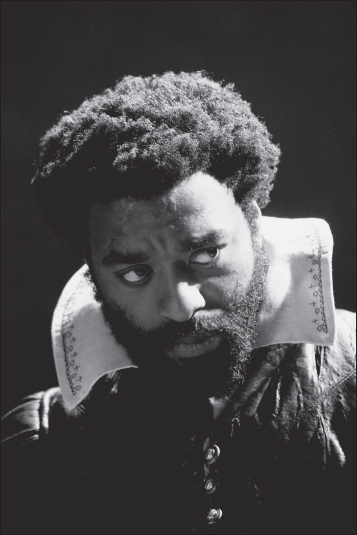

Chiwetel Ejiofor

on

Othello

Opened at the Donmar Warehouse, London on 4 December 2007

Directed by Michael Grandage

Designed by Christopher Oram With Michelle Fairley as Emilia, Tom Hiddleston as Cassio, Ewan McGregor as Iago, and Kelly Reilly as Desdemona

![]()

Othello was first performed in the very early 1600s. For the next 350 years the character was played almost exclusively by white actors who blacked up. When the famous African American actor Ira Aldridge played London’s first ever black Othello in 1825, The Times critic wrote: ‘Owing to the shape of his lips it is utterly impossible for him to pronounce English.’ Another objected to Desdemona being ‘pawed about on the stage by a black man’. Yet another described him as an ‘unseemly nigger’. Imagine those critics’ astonishment if a time machine could have whisked them forward to read the Guardian review of Chiwetel Ejiofor’s performance in 2007: ‘Ejiofor gave us everything we could hope for: the dignity, the rage, the self-delusion, the sublime word-music.’

Shakespeare had previously created two black characters. The Prince of Morocco is a foolish, pompous suitor for Portia in The Merchant of Venice, and Aaron the Moor a caricature of evil in Titus Andronicus. In Othello the playwright performed a remarkable balancing act. By making a black man his protagonist he invited stereotypical racist reactions from contemporary audiences, who might well have seen him as ‘the thick lips’, ‘the devil’ or ‘an old black ram’ – in the words of other characters. He then confounds expectation by establishing Othello as his dignified, multifaceted, tragic hero. It could perhaps be argued that he comes full circle when, at the climax of the play, Othello savagely murders his beautiful white wife in a fit of jealous rage.

Desdemona’s handkerchief is a central motif. It was Othello’s first gift to her, a token of his adoration. It is also a symbol of his mysterious past and exoticism. When she loses it, in Othello’s mind it becomes the proof of her guilt. This was famously ridiculed by Thomas Rymer in 1692. He called the play ‘A Bloody Farce’, whose plot hinged on nothing but a ‘little napkin’, and whose moral amounted merely to ‘a warning to all good Wives, that they look well to their Linnen’. Others would call it a brilliant insight into the hypersensitivity of jealousy, with its capacity to magnify even the most trifling incident into proof of betrayal.

Shakespeare uses a ‘double time’ scheme in Othello. One set of references suggests that a mere day and a half elapse between the arrival in Cyprus and the murder of Desdemona. Another indicates an interim of several weeks. The first enhances the pace and tension of the action, and supports the case of those who argue that the marriage could never have been consummated, while the second allows for greater dramatic plausibility. Considering that Shakespeare wrote for live performance rather than textual analysis, he may well have favoured the first of these. But maybe he intentionally held both in balance. Much has been written about this anomaly.

The play stands alone among Shakespeare’s great tragedies. What it lacks in the philosophical meditation of Hamlet and King Lear, it makes up in dramatic intensity. Audiences have often found the inexorable sweep to its tragic conclusion unbearable to watch. There are many accounts of spectators protesting, screaming or even fainting during the final scenes.

Chiwetel Ejiofor beat off extremely strong competition to win the 2008 Laurence Olivier Award for Best Actor when he played Othello at London’s Donmar Warehouse. It took many attempts to schedule this interview, but eventually succeeding was my reward for persistence. When we got together at Chiwetel’s London flat in September 2014 he turned out to be so relaxed and talkative that we ran out of time, and concluded our discussion with a follow-up session in May 2015.

![]()

Julian Curry: Most directors start rehearsals with a set idea in mind. Others prefer to coax a production into being via exercises and improvisation. Was this more one or the other?

Chiwetel Ejiofor: I’d say that Michael Grandage and Christopher Oram had a very strong idea of what they wanted, and the design was always in place. First of all it was going to be set in period, which for me really released the play. I thought it was a good way to approach Othello because the dynamics of the period are so interesting. Shakespeare clearly wasn’t concerned with modern ideas of race, multiculturalism and so on. The set was quite simple, having a contrast between Venetian streets with cobblestones and paving slabs, and the more airy, sunnier Cyprus.

Much of the play revolves around soldiers and soldiering, so was it a military setting? Did it evoke a barracks?

The council in Venice is brought together with the Duke and senators, and there’s a sense of government. The military aspect would come when they go to Cyprus to fight the Turks. But there was only a suggestion of that because the Turkish fleet gets decimated, so they wouldn’t have to set up a war machine. Othello is given the Governor Montano’s palatial residence and a lot of the action happens there.

I remember an excellent ambient background soundtrack to some scenes, quite discreet but wonderfully effective.

Yeah.

You first played Othello when you were eighteen with the National Youth Theatre. Do you think that performance fed into this one?

I do, yeah, mainly the emotions. I didn’t really understand the play at eighteen. Later on, of course, with a deeper appreciation of Shakespeare I got much more of it, and it became a more personal experience. But it’s always good to check in with yourself at different points in your life. It’s interesting how certain little things change over time.

I believe you were thirty-three when you did it again, which is younger than Othello seems to be in the text.

Something like that. I think I was even younger actually. The only real reference to his age is when he says at one point: ‘I am declin’d / Into the vale of years’ [3.3].

He’s also referred to as ‘an old black ram’ [1.1].

Yeah. ‘An old black ram / Is tupping your white ewe.’ That could mean anything. Thirty-one, or whatever I was, to her sixteen could certainly mean that.

So you never felt you should age up for the part?

No, I didn’t. I felt that Othello’s story could be relevant to any point in his life.

For centuries Othello was monopolised by white actors who blacked up, now the pendulum has swung and it’s a black actor’s part.

Well, that’s not entirely the case. Black actors such as Ira Aldridge and Paul Robeson played Othello centuries ago.

Okay, but in 1930 when Paul Robeson kissed his white Desdemona, Peggy Ashcroft, people were so shocked that they walked out.

Yeah.

Nothing like that happened in your production, I don’t suppose?

No. [Chuckles.]

So things have moved on.

Paul Robeson and Peggy Ashcroft kissing on the West End stage in 1930 may have shocked some with provincial mentalities, but most people stayed, most people didn’t give a shit. Now, I don’t think they could have kissed on the London stage in 1955, for example, without it being shut down. I believe that the war created much more nationalistic spirit than existed before. I did a series [Dancing on the Edge in 2013] by Stephen Poliakoff about a black jazz band arriving in the UK in the 1930s, and their involvement with the aristocracy and other experiences, which are all true and well documented. And how in preparation for war and during the great violent conflicts of 1939 to 1945 there was a galvanising of nationalistic identity, which also evoked a sense of racial hierarchy. What I’m saying is the politics of the time changes the direction of the play. It’s not linear.

How did you prepare for Othello, being a soldier? Did you work out physically, or were you fit enough already?

I was pretty fit, so I didn’t go into a full-on physical preparation. And although he’s spent much of his life fighting, he has become general of the army. Therefore he doesn’t necessarily have to be on the front line any more, he can control operations from further afield. I think his history and his psychological journey are what’s most important.

In his final speech, Othello describes himself as ‘one that lov’d not wisely, but too well’. How well does he know Desdemona? Was she ever perhaps a trophy white wife, with ‘skin… smooth as monumental alabaster’ [5.2], or was it a genuine love match from the start?

That’s a good question. It depends on how you see it.

How do you see it?

I saw it as absolutely that he fell in love with her. What he describes is exactly what happened. Brabantio invited him, they became friends, and Brabantio was thrilled to have this exotic guy in the house, and pleased for him to tell his stories and impress the children. And in the course of doing so, Othello notices that the girl is extraordinarily interested not only in his stories but in him. He realises that she is falling in love with him. He sees, I suppose, a softness in her gaze that he’s quite unused to. Her gentleness and her beauty are intoxicating to him, and because of this adoration he finds himself falling in love with her. And so there probably isn’t a deep knowledge of each other, as much as a powerful awareness of the emotion they’re both feeling. He is also attracted to her willingness to break through societal constraints. I don’t think there’s any evidence in the text that he considered her to be merely a trophy.

I imagine Othello has had plenty of sex at various times in his life. But is this the first time he’s been in love?

Absolutely. Othello’s never been in love before. He’s shell-shocked by the emotion. He had no idea that one could feel anything like that. He’s been through terrible trauma, including being in the Arab slave trade, and has largely shut down the emotional side of himself, and filtered it into conflict. That’s where he has always felt most alive, as he describes, in the ‘Pride, pomp, and circumstance of glorious war’ [3.3]. He’s not looking for anything to replace that emotion, which is why she completely catches him off-guard by falling in love with him. It’s not something that he expected or even necessarily wanted. But it certainly is the first time he’s experienced it.

He married her in secret, quite hurriedly, without her father knowing.

Sure.

Therefore he did deceive Brabantio, who has every right to be furious. But there’s no sign that Othello is bothered by that.

No. Because he knows what Brabantio is about in that context. He knows that Brabantio is essentially a racist, which he proves to be.

So it wouldn’t have worked to ask his permission, or tell him in advance – is that your thinking?

Yeah. He would have banned the marriage. Othello has the measure of Brabantio completely correct, as is proved by his subsequent behaviour. If Brabantio later came out and was like, ‘Why didn’t you just tell me? I was cool with it…’, then that would have been one thing. But clearly Brabantio is a racist, and although he likes Othello in the context of his exoticism, he would not take kindly to him marrying his daughter. So Othello takes the situation out of his hands and says: Well, we can’t do it that way, let’s do it this way.

With Othello what you see is what you get. On the other hand, Iago has a facade that he shows to other characters, and then by contrast what’s really going on inside, which is why therefore he needs lots of soliloquies. They’re also a great way of forging a relationship with the audience, and Othello has very few. Did you miss them? Do you think Shakespeare short-changed Othello in that respect?

He made Othello one of the most lyrically gifted characters in the entire canon. I don’t think there’s anyone in Shakespeare who speaks with more distinct, clear beauty. The account of his meeting with Desdemona is wonderfully exotic, and the way he describes his love for her later on, with ‘Had it pleas’d heaven / To try me with affliction…’ [4.2], is completely heartbreaking. Instead of soliloquies and direct engagement with the audience, Shakespeare gives Othello something very beautiful, with an earnest depth to it. And by keeping him at a slight distance from the audience they can really observe this man go through his experiences and express himself, without having to explain and break the fourth wall. I think this removal gives him an almost angelic status, it’s as if by not engaging with us directly he’s kind of beyond this world.

When you consider what happens to Othello, and the number of times he refers to ‘honest Iago’, there must be a danger of him seeming to be a dupe, a credulous fool – which would diminish both the part and the play. But I suppose the fact that he’s been a soldier since the age of seven, as he says, is very significant. It must condition his whole outlook on life. I imagine that for a soldier, trust in your comrades is paramount, part of your DNA almost. So the idea of Iago betraying him would be less likely to occur to him than it might to a civilian. Is that making sense?

Yeah. It’s a relationship of life and death. Othello is a foreigner, and it isn’t that he’s credulous or a dupe. He has certain criteria in terms of the people he surrounds himself with. One of the most important is how they perform in battle, how they act under pressure and whether they are sturdy and of good heart and spirit. And of those that are, the cream rises to the top in his mind. In that context, Iago is an incredibly good ancient, he is the kind of man that when the flag goes down, picks it up and runs with it. Othello has seen that all over the world, in Rhodes and Cyprus, on grounds Christian and heathen. So it absolutely wouldn’t occur to him for a second that Iago might betray him. He could have done so at any point, but has proven himself to be a valuable ally and an excellent soldier.

In that case, why did Othello make Cassio his lieutenant?

I suppose because he believed that Iago was very specific to the position of ancient, who is his right-hand man in the field. He’s not necessarily capable of making brilliant theoretical decisions, but an extraordinarily loyal soldier who is valuable in the practical whisperings of: Don’t do that, do this. Cassio he probably sees as somebody who knows more of the scholarship of soldiering, would be more capable of running the army at some point, maybe even of taking over from him. So Othello makes a perfectly informed decision to appoint Cassio as his lieutenant, and to keep Iago as his ancient. In some ways it’s a compliment to his appreciation of the guy. But Iago interprets it as thoroughly negative.

When Desdemona refers to ‘Cassio, / That came a-wooing with you’ [3.3], it seems a bit strange to me. That’s odd, isn’t it?

Oh, guys do that all the time. These days it’s called a wingman.

Oh, is it? Okay. I shall bear that in mind next time I go a-wooing. So giving Cassio the post of lieutenant isn’t just nepotism?

No. They developed a friendship, but I don’t believe that was the motivation. Othello is a man of war, a man of violence, and everything boils down to that. That’s why he kills Desdemona in the end, because violence is his way when all other means of negotiation fail. As a man of war is how he makes his decisions. I think he selects Cassio within the context of the wars and what they’ve experienced together and what he sees of him as a soldier. After that he gets to know people, and in times of peace he looks to someone like Cassio to help him figure out certain things he doesn’t know about, so maybe they would go a-wooing together.

In the past, many famous Othellos were extravagantly histrionic. They were acclaimed for their lion-like fury, exotic barbarity, ferocious animality. The advent of film and TV has tended to make the style of acting in general more naturalistic and less flamboyant, therefore more in favour of Iago who is basically down to earth and prosaic. Is that an impediment to playing Othello nowadays?

I think you adapt to where you are. For example, the Donmar where I was playing, being a small and intimate space, is given to a wonderfully focused intensity. It was great to have – for want of a better expression – that kind of leaning-in atmosphere from an audience.

But you couldn’t be extravagant in the way you might in a two-thousand-seater?

I suppose that would be different in the sense that you’d want to hit the back wall and you could let rip. Incidentally, I saw Laurence Olivier’s Othello on a DVD. He was often accused of being too big, but I thought it was brilliant.

Did you?

I did, absolutely.

I was completely knocked out by it on stage. But I never wanted to see the film because so many people said his performance came across as hammy and over-the-top.

I didn’t think that. I thought it was superbly well crafted, with a beautiful sort of undulation. I couldn’t imagine better handling of Shakespearean verse. And in terms of whether I felt he was jumping out of the screen, or was completely over-the-top, no I didn’t. The emotions of Othello are incredibly dramatic. I guess I had reservations about Olivier’s depictions of blackness, but once I put that to the side I thought it was pretty amazing.

Othello is willing to fight the Turks, so presumably he’s not a Muslim. Has he adopted Christianity?

No, he’s a Christian by birth.

He says in his first scene: ‘I fetch my life and being / From men of royal siege’ [1.2]. Is that compatible with being a freed slave?

Well, yeah. His background is perceived as very urbane. When he talks about his mother he gives the impression that she was worldly and elegant. She got this exotic handkerchief as a gift from an Egyptian enchantress, and gave it to Othello on her deathbed. Being sold into slavery was obviously subsequent to that, another part of his life.

You’ve written that you always thought of Othello as a sequel to Romeo and Juliet. Can you explain why?

I did Romeo and Juliet at the National in about 2000, and in approaching Othello I was struck by the similarities between the two plays. When Romeo falls in love with Juliet it creates this kind of blip, like a submarine on the radar, and all guns are trained on it. Love is vulnerable and difficult, and is manipulated by others for their own agendas. And in Othello it’s the same, but instead of the Montagues and the Capulets, the forces of repression are represented by Iago. In both plays you have this beautiful and precious, innocent love which is destroyed by outside pressures that are duplicitous, aggressive, angry and cynical.

You never made a film of the production, did you?

No, we didn’t.

Was that by accident or design?

I think we had plans to make a film at a certain point, but it just didn’t materialise. It’s hard to make Shakespearean films, to get the kind of crossover audience you require. Apart from [Baz Luhrmann’s] Romeo + Juliet with Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes and Pete Postlethwaite, I can’t remember a Shakespearean film that has actually reached a substantial audience. And with Othello you would really need to be in the wars and the travels, and so you’re looking at a larger budget.

Also that Romeo + Juliet was a film of Shakespeare’s text, not of a stage production, which yours would have been, and therefore adapted from one to the other.

Sure. So to translate what happened on stage on to film would have been complicated. I’m sure Michael would have been able to do it, but the budgetary constraints would perhaps have impinged on the overall quality.

In Othello’s first scene Iago asks ‘Are you fast married?’ [1.2], which I believe means ‘Have you consummated the marriage?’ What’s your thought about that?

I didn’t think they’d had sex.

Not ever?

Certainly not at that point, and probably not at all. The night of Cassio’s brawl is the time when they might have been about to consummate the marriage. But the brawl interrupts them, which adds to Othello’s fury on that entrance. Actually he never answers the question ‘Are you fast married?’

No. You just gave a little chuckle, a nice sort of non-committal chuckle.

Exactly. He wouldn’t answer a question like that. He would give a noncommittal chuckle either way.

Act 1, Scene 3. Othello meets the Duke and senators. He opens with ‘Rude am I in my speech’ and then proceeds, like Mark Antony in Julius Caesar, to be hugely eloquent.

And unrude.

Exactly. But given to remarkably pompous and ornate language. He calls his eyes ‘My speculative and offic’d instruments’ – a most outlandish turn of phrase. Is he trying to impress them?

Of course. He’s accused of being a brute and undeserving, by definition because of his race. So he turns it on its head and says not only am I the general of the army, I’m also a perfectly eloquent and intelligent human being who’s lived one hell of a life. So get out of my way!

With one hell of a vocabulary.

Yeah.

But he goes on to talk about ‘The Anthropophagi, and men whose heads / Do grow beneath their shoulders’. Who’s he trying to kid? That’s absolute nonsense, surely!

I don’t think it’s outside the realm of possibility. Look at the cages and the zoos of the Elephant Man era. We don’t know the history of all the different groups of people who have populated the planet, and may have become extinct. What we do know is that people come in all shapes and sizes. We know that there are pygmy tribes, people who are diminutive but perfectly formed, and aggressive. If you imagine them running at you in numbers they could appear to be men whose heads grow beneath their shoulders. We don’t know that he’s lying, and it’s something that Shakespeare could have believed to be factual.

Othello describes the wooing of Desdemona with a long, wonderful speech. It seems to me he was well aware of cutting an exotic and charismatic figure, and used it to beguiling effect. In other words, maybe Brabantio was right, and in his own way Othello was using charms and spells. Was he doing so consciously?

It’s an interesting question. When he’s first invited by Brabantio I don’t believe he’s consciously being beguiling, or duplicitous in any way. He has an open heart and is extremely good at expressing himself. He doesn’t have in mind that he is, at the same time, wooing Desdemona. So he wouldn’t consider it a spell initially. But once she shows special interest, then he takes pleasure in telling her his story in the most romantic and idealised way he can, knowing the effect that it has on her.

On the question of whether Desdemona will go with him to Cyprus, she says if she’s left behind in Venice, ‘The rites for why I love him are bereft me’ – which could refer to sex, but doesn’t necessarily. Othello then urges the Duke to let her accompany him, but adds: ‘not / To please the palate of my appetite, / Nor to comply with heat the young affects / In my defunct and proper satisfaction.’ He seems to be implying he’s past it, and not interested in shagging her. If you were thirty-one at the time, that’s hard to believe.

Indeed. [Chuckles.] Leonard Cohen’s song ‘Hallelujah’ refers to the idea that love changes a man and makes him less capable. But I think he’s trying to convince the court that he’s the same general as he was before. With his new wife he’ll be just as dedicated, if not more, to the cause of fighting. Having her with him will be a help, not a hindrance.

But it doesn’t work out like that.

It certainly doesn’t.

It’s a catastrophic mistake. And for a soldier to take his wife with him on active service is normally out of the question, surely.

It’s interesting. I don’t know whether that is applicable to the elite, to the generalship. Sure, if you’re a grunt, a sergeant, you’re not going to take your wife. But if you are the head of the army, the General Petraeus, maybe you’d be able to do that. I never thought of it as far-fetched that Othello and his ancient would have their wives with them. Cassio has a girl in Cyprus, so he’s fine, and the other soldiers would be the same.

Brabantio has a prophetic exit line: ‘Look to her, Moor, if thou hast eyes to see. / She has deceiv’d her father, and may thee.’ Othello responds with ‘My life upon her faith!’ But was any part of you inwardly disturbed by that, even so early on, and afraid it could come true?

It’s a great line that cuts through the facade of Othello’s reality. It is an absolute dagger, because it suggests a secret knowledge. Othello believes, as the general of the army who has married Desdemona, that he has the knowledge. But Brabantio says to him, Let me give you some of the secret knowledge, the stuff we don’t say: If she lied to me, she can lie to you.

So the seed is sown.

Totally. There may be things he doesn’t know about her, about their relationship. And of course Iago just fertilises that idea.

The scene ends with a soliloquy from Iago. He says ‘I hate the Moor, / And it is thought abroad that ’twixt my sheets / He’s done my office.’ And later [2.1], ‘I do suspect the lusty Moor / Hath leap’d into my seat.’ Is there any chance that Othello has slept with Emilia?

Absolutely not, no. Iago’s mad. He’s insanely jealous and insecure, he is reaching for ways of destroying Othello and he’s going to find them. He has the classic anti-Arab bias described in Edward Said’s Orientalism. That’s just one of the things he comes up with as a reason for this brutal betrayal.

Act 2: they move on to Cyprus. Othello seems relaxed and at the peak of happiness, telling Desdemona ‘I prattle out of fashion’ [2.1], then leading her off to bed with ‘Come, my dear love, / The purchase made, the fruits are to ensue’ [2.3]. But they are interrupted by the brawl. You’ve suggested that his fury is fuelled by coitus interruptus.

It was, yeah, I felt.

But Cassio was well out of order, wasn’t he, so presumably you were also furious for that reason.

Sure. It’s not just the coitus interruptus. Cyprus is still on alert, they’re on watch and Cassio is in charge of the guard. I’ve been in places such as Ngoma and Congo, in my real life, with people unsure whether the rebel army was going to attack, or if the UN soldiers could protect the road into Ngoma. So I’m very aware of what that sort of tension is. If the soldiers start fighting each other, and a brawl spills out involving a high-level person such as a lieutenant, it is obviously a clear sackable offence.

So it was a severe breach of discipline, and he deserved the punishment.

Absolutely.

In the very short Act 3, Scene 2, Othello dispatches some letters. Any idea what they are?

He sends them back to Venice. He has to give a detailed report of the situation on the island, what the provisions are, and the plans. He needs to know if ships are to be sent out, whether any further investigation of the Turkish movements is required.

On to Act 3, Scene 3. The amazing long scene which goes from adoration of Desdemona to a frenzy of jealousy.

I remember it well.

I’m sure you do! Iago seems effortlessly to wind Othello round his little finger. He must know him well, and understand his weaknesses and vulnerabilities.

Yeah. I think the scene works so successfully because Iago’s aware that Othello is very smart, he’s an intelligent man. And so in order for this whole thing to succeed he has to layer it in very delicately. He plays off the fact that Othello doesn’t miss a trick. There are a couple of times he almost doesn’t get away with it. In that sense it becomes an intricate chess game, which Iago plays incredibly well. He doesn’t come out with any strong statement, nothing blunt until much later on. It’s all: Did you catch that? And Iago knows that Othello’s going to respond and ask him, Why are you talking to me? What are you saying? Why would anybody talk to their superior in this way? And through that process he plants the seed of doubt, which eventually unravels Othello.

You said it almost goes wrong a couple of times. Such as?

I think Iago is surprised by the starkness of Othello’s response. He says very simply: Prove it! ‘Villain, be sure thou prove my love a whore’… or I’ll kill you.

Early on in the scene, when Desdemona pleads for Cassio’s pardon, she’s asking Othello to undermine military discipline. In relenting and saying ‘I will deny thee nothing’, he is reneging on the promise he made in the first scene, that he wouldn’t allow her presence to influence him.

I think she’s asking him to have an audience with Cassio, to speak to him, and that’s what he relents to. Is that reneging on his promise? He’s not saying he is going to pardon Cassio, he’s saying: Let him come to dinner, I will speak to him. He’s bound to have a conversation with Cassio at some point. He may be just putting it off because he doesn’t want to fire Cassio.

She exits and he says ‘Perdition catch my soul / But I do love thee!’

‘And when I love thee not / Chaos is come again.’ Even in the declaration of love, you’re looking at the tragically destabilised platform he’s standing on. He understands that there is chaos round the corner if things go bad, if she’s holding back secrets.

Soon afterwards Iago starts parroting Othello. He repeats ‘indeed… indeed; honest… honest; think… think’. Othello says ‘thou echo’st me / As if there were some monster in thy thought / Too hideous to be shown’. Iago has planted the seed; how quickly does it begin to grow?

As soon as Othello catches on to Iago saying ‘Ha? I like not that’, on Cassio’s exit, he’s on the train. In my opinion this scene hasn’t got the arc that some people perceive it to have. It’s not from adoration to jealousy, hatred and fury, it’s from an awareness that he doesn’t truly understand Desdemona, to a conviction that her private thoughts are love for Cassio. Which is a slightly different journey. What Iago is doing is activating the enzyme. He’s using the emotional energy that Othello already has.

So he really doesn’t know her well.

He doesn’t. He’s in an insecure position. These are men of war who go off to Cyprus to fight, and find there’s no war. They are simply stranded on an island with nothing to do. This is the first time he’s really thought about her. He wants to start a family and do all the usual things. He is not given to examining her in that way, wondering: Who is she, what does she think and does she love me? His job is killing Turks, but now all the Turkish ships have sunk and they’re in Cyprus with no councils, no Brabantio, nothing. There’s just her and him and figuring it out.

Halfway through the scene, Iago exits and Othello has a rare, short soliloquy. His assurance seems to be melting away, the poison is taking effect and he’s becoming convinced of Desdemona’s guilt. She returns and he says ‘I have a pain upon my forehead, here.’ Has he actually got a pain, or does he imagine he’s growing cuckold’s horns?

I don’t believe Shakespeare’s writing symbolically about cuckold’s horns. I think Othello literally has a storming headache. He has a fever about this possibility, he’s in torment about the idea that she has betrayed him. He may be about to faint or go into an epileptic fit. So Desdemona offers her handkerchief, saying ‘Let me but bind it hard, within this hour / It will be well.’

She drops the handkerchief, which is essential to the plot, but surprisingly clumsy. How did that come about? It seems an odd thing to do.

No, he drops it.

Oh, he drops it.

Yeah. He drops it and she doesn’t pick it up. He says ‘Your napkin is too little. Let it alone.’ He snatches it away and in the kerfuffle, with Emilia there and everything, she doesn’t notice. He says ‘Come, I’ll go in with you’, and it gets left behind. I think that’s what we did.

He returns soon afterwards with ‘Ha, ha, false to me?… Oh, now forever / Farewell the tranquil mind! Farewell content! / Farewell the plumed troops, and the big wars / That makes ambition virtue – O, farewell! / Farewell the neighing steed and the shrill trump…’ and on he goes at some length. It’s wonderful stuff, but he’s quite a self-dramatist, isn’t he!

It depends on your emotional state. That speech is, to me, one of the most exceptional pieces in the play. It’s heartbreaking and I empathise with it as an actor. If she has been unfaithful to him he feels betrayed of all of his essential qualities, so he can’t be a soldier any more. He can’t go in front of the army, he can’t order people into battle, he can’t do any of it. Therefore he feels in that moment that her betrayal ends him as a person.

I suppose what I’m getting at is that Shakespeare’s characters are to an extent defined by how they express themselves. For instance, Romeo in love talks in one style, Beatrice in love talks in another style, and Bassanio in yet another. Othello’s way of saying what you’ve just described is very much in terms of his own glory and self-regard, which he feels has been trashed, lost.

Okay, but he is talking about it in the context of what has gone. So Shakespeare makes it as glorious and amazing as it is in his own mind. Othello’s nature and his dedication endeared him to me, he’s so passionate and so believes in these things, which I don’t believe in. I don’t believe in war, but he does. He’s imbued with the idea of it, and its historical, poetic context. He really is a warrior. If you read the poem ‘Invictus’ [by William Ernest Henley] you get that sense of personal responsibility: ‘I am the master of my fate, I am the captain of my soul.’ Those ideas are encapsulated by Othello, he absolutely buys the notion that war, violence, self-reliance, independence are the centrepiece of human existence.

‘Villain, be sure thou prove my love a whore! Be sure of it; give me the ocular proof…’ The stage direction says ‘He seizes Iago by the throat.’ Did you do that?

Oh, yeah, we played that. There has to be a major threat of physical violence. I think I grabbed him by the throat.

Would you say that was when Othello starts losing it?

No. I think it’s a perfectly rational response to somebody who tells you this, but offers no hard evidence. That’s fighting talk where I come from. It’s like if you tell a guy his girlfriend’s been sleeping around, but offer no explanation. He turns around and says go fuck yourself. It’s perfectly reasonable. But it encourages Iago, because it shows him that what he’s doing is working.

‘I think my wife be honest, and think she is not. / I think that thou art just, and think thou art not… Would I were satisfied!’ Othello is in an agony of uncertainty. When he says ‘If there be cords or knives, / Poison, or fire, or suffocating streams, / I’ll not endure it’, is he talking about killing himself or Desdemona?

He’s talking about killing them both. He’s talking about killing it, whatever it is. Killing this feeling, killing this emotion. I suppose he starts off thinking about her and ends up thinking about himself. ‘If there be cords or knives, / Poison…’: I think from the moment he mentions poison it starts to turn. He could take the poison as well.

That’s what he ends up doing of course, killing both of them.

Exactly. The only solution was for them both to die.

Iago removes Othello’s uncertainty first by the fabrication of Cassio’s erotic dream, and then the fortuitous handkerchief. Earlier on, Iago subtly manipulated the situation without ever saying anything outright. But at that point…

At that point he says it very clearly. Othello would have no reason to believe Iago is lying, but what he wants is proof. He calls the dream ‘monstrous’, and it is monstrous either way. Even if nothing was happening between Cassio and Desdemona, for him to have dreams that were reflections of his desires in this way is a terrible thing. But Iago then supports it with proof, and the handkerchief represents the final straw. It was a token of marital love and fidelity that his mother passed down to Othello. And in his mind there is absolutely no way Cassio could be in possession of that handkerchief, unless Desdemona had given it to him.

Having got the proof he was asking for, Othello says ‘All my fond love thus do I blow to heaven – / ’Tis gone.’ What did you do?

I think I demonstrated it to Iago, blowing out with a cupped hand. I just love that idea. There was a film about ten years ago called Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind [written by Charlie Kaufman]. Essentially it talks about the same thing, the possibility that you could wipe away a relationship. So if you have a bad break-up, you could just erase the memory of this person from your life. What happens in the film is that Kate Winslet meets Jim Carrey, and they’ve got no recollection of the long relationship they had in the past. If only Othello could do that! ‘All my fond love thus do I blow to heaven…’ [Blows.] And it’s gone. I’ve expelled it, I’m fine. I’m totally fine.

But of course it’s not so simple, and a minute later he’s saying ‘Oh, blood, blood, blood!’ – which sounds like frenzy. Tell me about that: how did you suit the action to the word?

I think I sank to my knees downstage centre. The words represent the anguish of it all, and the fury, and almost a terror of what he was going to do with this knowledge, and the pain, the terrible searing pain of a broken heart, of a man brought to his knees by love and the idea of it being lost or taken away, as all other things have been in terms of family, in terms of his dignity – his dignity regained after slavery but here, again, the worst sort of crippling indignity, to be humiliated by your wife and your lieutenant. ‘Oh, blood, blood, blood!’ is all that comes to his mind.

When Iago suggests he may change his mind, Othello responds with a tidal wave of the most thrilling verse. ‘Like to the Pontic Sea, / Whose icy current and compulsive course / Ne’er feels retiring ebb, but keeps due on / To the Propontic and the Hellespont, / Even so my bloody thoughts, with violent pace, / Shall ne’er look back, ne’er ebb to humble love, / Till that a capable and wide revenge / Swallow them up. Now, by yon marble heaven, / In the due reverence of a sacred vow, / I here engage my words.’ You probably remember in the film that Olivier tore the crucifix from his neck at that point, symbolically renouncing Christianity. Did you do anything similar?

No. To me he would never renounce his Christianity. That could perhaps be a valid choice, depending on how you approach the play. But it would never be my choice. It’s not up for grabs. Christianity is his raison d’être. It is the saving factor in his life, although it led to his enslavement. That was when he might have renounced his faith, and he did not. It was also the reason that he reached his position. The Venetians recognised him to be not just a Christian but a man who has a pathological hatred of Islam, and that’s why they put him at the head of the army to fight the Turks. At the end of the play, in my opinion, he discusses himself as a Christian and kills himself as a Christian. And his justification for killing Desdemona is based on the Christian ethic. But at this point I think he is certainly bringing up the other side of his nature, what he considers to be the buried side of his nature. This is why I think it might have been a valid choice for Olivier to rip off his crucifix. But I don’t think he’s renouncing Christianity. Essentially he’s not saying ‘I’m less than Christian’, he’s saying ‘I am more than Christian.’

As the scene ends, Othello commands Iago to kill Cassio. He exits with ‘I will withdraw / To furnish me with some swift means of death / For the fair devil.’ Notably, it’s he who resolves to kill Desdemona, and the idea doesn’t come from Iago, who actually says ‘let her live’!

That’s right.

Moving on to Act 3, Scene 4. Othello tells Desdemona, ‘That handkerchief / Did an Egyptian to my mother give.’ And later, ‘There’s magic in the web of it’, followed by a wildly exotic account of its creation, which again sounds as if he does believe in spells. But he seems to contradict himself because in the fifth act he calls it ‘an antique token / My father gave my mother’ [5.2]. Does that matter? Is he confused?

Interesting. I think I felt that essentially both things are true. The Egyptian charmer gives his mother the handkerchief, and talks about it in the context of his father. That is to say he tells her – maybe I’m paraphrasing a little – if you keep this handkerchief your husband is always going to be true to you. But if you lose it or you give it to somebody else, then you’re in for chaos. So in Othello’s mind it is essentially a trusted token between his father and mother. Yes, there is magic in the web of it, which he interprets like a wedding ring. So they become one thing in his mind.

There are often implicit stage directions in Shakespeare’s texts. For instance, Desdemona asks ‘Why do you speak so startingly and rash?’ Did you find that helpful?

Oh I love it. Well, it’s Shakespeare. You definitely want to be aware of those things because they map the psychological journey. Of course you can take them out, she could cut her line and you could not act startingly and rash, but you’ll find that Shakespeare is guiding you towards something. That ‘startingly and rash’ is the beginning of the fit, which happens soon after. You need to place in the story the fact that he’s starting to lose a grip of his physical self.

I remember you played the following line – ‘Is’t lost? Is’t gone? Speak, is’t out o’ th’ way?’ – highly agitated.

Sure.

Act 4, Scene 1. Othello and Iago enter in the middle of an animated conversation. What’s the backstory?

Othello has been vacillating, and Iago is pushing for the conclusion – ‘to be naked with her friend in bed / An hour or more, not meaning any harm?’ He is goading Othello, who obviously doesn’t want to kill her. He’s very clearly trying to rationalise himself out of it. And Iago is trying to get him back on track.

Then Othello collapses. How did you interpret what happens to him? Did you look at medical records, did you talk to consultants, did you use your own intuition? What is the fit?

I approached it emotionally. The fit to me was a kind of hysteria that shuts down his body, like fainting. There’s a line that Cassius has to Brutus about Julius Caesar: ‘And when the fit was on him, I did mark / How he did shake.’ And he mocks Caesar for crying out ‘Give me some drink, Titinius’, ‘As a sick girl’. That was the image I had for what Othello was going through, and what Iago would witness so that he could say ‘Work on, / My medicine, work on.’

Tell me more about the fit, which is such an extraordinary moment. It’s noticeably the first time Othello speaks in prose, and you did much of it extremely slowly.

The stagecraft of the fit is very difficult. It’s a great challenge, I think, because you’re deep into the play at this point. It’s after the interval so you’ve had a cup of tea or a half-time orange, and you come back out having declared that you’re going to kill this woman. Just in terms of physical stamina, the part is incredibly challenging due to the way theatre is scheduled these days, often with eight shows a week. Maybe you’ve already had a matinee. You want to commit to a full epileptic fit because it kind of represents a tempest, it represents the absolute fall of man. However, you still have Act 5, with the extraordinary murder.

You’re talking about pacing yourself?

Yeah. And this is where the prose helps. Because if it was in verse then you would have no choice but to thoroughly commit to the poetic rhythms, which would mean that I don’t think you’d have an Act 5. But with those few minutes of prose you can, at that point, pace yourself. You can break it up, you can do something very different, which doesn’t require the same rhythmic pulse. I feel it’s almost as if, when they were doing the play for the very first time, the actor couldn’t commit to that moment entirely, because to give it full poetic intensity would mean there was literally nowhere to go. So Shakespeare recognised he needed to do something different with that beat, and he made it into prose.

After the fit, Othello is up on his feet again quite soon. Was there a hangover, did you feel that you recovered from it completely?

I think the nature of his anger changes. Beforehand he was in a rage that sent him into a kind of chemical and physical imbalance, where he was out cold. Once the fit is over he’s in a fury, and outwardly he seems calmer. He is not going to get into that state again. He’s not going to have another fit, he’s going to get revenge.

That leads into the eavesdropping scene. There was a famous eighteenth-century Italian Othello called Salvini who cut the scene completely. He said it was implausible, because Othello would spring like a tiger on to Cassio and tear him to pieces. Did that thought occur to you?

No. Of course he could, but what’s brilliant is that he doesn’t, although the impulse to kill him is massive. I think it’s so impressive and interesting that even then Othello organises his life around a decorum. After Cassio’s fight, Othello said to him ‘In night?’ If you’re fighting in the daytime around the corner, well, that’s one thing. But you’re fighting ‘In night, and on the court and guard of safety?’ [2.3]. It’s incredulity that you’re doing this outside the rules that we have organised. And so part of Othello’s rationale is always how to do certain things within the context of military rule, which is why he can’t simply rush out and stab Cassio where they are, no matter how much he wants to. He has to furnish it, he has to think about it.

Even when he’s starting to go mad?

Totally. That’s why he kills Desdemona the way he does. He tells her to go to bed, and Emilia to prepare her well. It’s part of his formality. He can’t just kill her, it has to be done by him correctly as a military person and a high-ranking officer.

Desdemona enters with Lodovico and Graziano, and Othello strikes her in their presence. He’s losing self-control. Did you hit her hard, did she fall over?

Obviously it was a stage slap, but yeah she fell and hit the deck. It’s a heartbreaking moment. The scream of ‘Goats and monkeys!’ is horror at himself, at his violence towards Desdemona and insane lack of restraint. There’s also the sense that he’s still fighting with himself, in a way, not to kill her. But he’s so racked with jealousy at this point that he can no longer control his impulses. Striking her is an indication of how far they are taking over.

That’s after ‘I will chop her into messes’. But you’re saying that he still hasn’t really decided?

Every time, he says I’m gonna kill her, I’m gonna kill her, and then we have another scene between them. Maybe something moves forward, but he’s not killing her. He’s at war with himself.

Act 4, Scene 2, which some critics call the brothel scene. Why do you think that is?

Maybe because he pays Emilia at the end. He says ‘We’ve done our course; there’s money for your pains. / I pray you turn the key, and keep our counsel.’ At that point, Othello is imagining Emilia as the keeper of a brothel and Desdemona as a prostitute.

Again the scene starts in mid-conversation, this time with Emilia. Did you externalise symptoms of suspicion? Smell Desdemona’s sheets or anything?

No. In this episode, Othello actually has a moment of clarity. He interrogates Emilia to find out what’s been going on. He realises that if anybody knows, she does. He asks ‘You have seen nothing then?’ and Emilia answers ‘Nor ever heard, nor ever did suspect.’ Othello insists: ‘Yes, you have seen Cassio and she together… Did they never whisper… Nor send you out o’ the way?’ Emilia just says ‘Never, my lord.’ He says ‘That’s strange.’ For the first time there’s a glimmer of hope that it might occur to him that Iago has been lying.

Because it is strange if Emilia hasn’t seen anything. But then he can’t 100 per cent trust Emilia, that’s the problem. He calls her ‘A closet, lock, and key of villainous secrets.’

Desdemona enters and makes desperate pleas of innocence, but Othello seems deaf to them.

I don’t believe he’s deaf to them: he’s in a completely different psychological state. He’s in a universe of regret and remorse. I think if, even at this late stage, she could find some way of really convincing him, he would still love to hear it. But he’s beyond that.

What happened between you? Was there more physical abuse?

No. Kelly [Reilly] was kneeling in a kind of prayer, and I knelt with her. She was crying and I was holding her, and there was a point when I was wiping away tears from her face.

Othello says ‘Ah, Desdemon, away, away, away!’ Presumably she was clinging to you?

Yeah. I think I stood up on ‘Had it pleas’d heaven…’, which, to me, is the most heartbreaking speech in the play, because Othello is saying, Look, I could go with anything else, I could have handled absolutely anything.

Had it pleas’d heaven

To try me with affliction, had they rain’d

All kinds of sores and shames on my bare head,

Steep’d me in poverty to the very lips,

Given to captivity me and my utmost hopes,

I should have found in some place of my soul

A drop of patience; but, alas, to make me

The fixèd figure for the time of scorn

To point his slow and moving finger at!

It is one of the most exquisite pleas to heaven in the English language.

He goes on ‘But there, where I have garner’d up my heart…’ What does he mean by ‘there’? Is he talking about anywhere in particular?

It’s non-specific. He had met this girl and been totally blown away by the new emotion, by this feeling that he’d heard about but had never experienced. As a result, what is happening now is the most painful thing he’s ever suffered. And he cannot understand it. So when he says ‘But there, where I have garner’d up my heart’, he’s a man who is completely flummoxed, he’s knocked for six. He had never dreamed that could happen to him, or that this kind of agony was possible.

Act 4, Scene 3. Desdemona sings the haunting ‘Willow song’. At the beginning of the scene, Othello tells her: ‘Get you to bed / On th’ instant; I will be return’d forthwith. / Dismiss your attendant there – look’t be done.’ And he exits. Once again, it’s in front of Lodovico. If he’s planning the assassination, he doesn’t care about being overheard.

I don’t think he has any intention of getting away with it. There’s no sense of subterfuge.

It seems dead cold.

Yeah. He’s going to kill her, and he has ordered the death of Cassio. So they will both be dead. He will be arrested, and explain that they have been having an affair, and throw himself on the mercy of the court and try to prove his case.

On to Act 5, Scene 2, the final scene. How was it set up? Did you have a bed wheeled on? Was it a four-poster?

I don’t think it was a four-poster, but it was very ornate and regal. It had bold reds – beautiful. I wore a long flowing gown and was holding the lantern with a candle.

Othello’s opening line is ‘It is the cause, it is the cause, my soul.’ What does he mean? What is the cause?

I think that’s all of it. It’s Christianity, it’s military, it’s the reason to be. It’s her. She is it. They are it. It’s a multifaceted cause.

Desdemona is in the bed asleep and Othello says ‘Put out the light, and then put out the light.’ Then he explores a metaphor for doing so.

It’s an interesting metaphor because there are two ways of playing it. Either he’s about to put out the light, and then it occurs to him that he’s also going to put out the light of her. Or he realises beforehand and the whole line is driving towards the metaphor, which would be more lightly stated. I think I found it in the moment. He makes an allusion to the fragility of life, to the difference between a live flower and a dead one.

This final scene is an astonishing cocktail of sex and death. He’s entranced by the sight of her, her smell, her balmy breath and beautiful smooth white skin. He kisses her three times and then he kills her. It’s unbearable to watch. What is it like to perform?

It is one of the most extraordinary scenes ever written. He’s desperate to have sex with her, and she has prepared herself for it. The sexual tension between them is massive. But then in a sense Cassio is also in the room, when Othello tells Desdemona that he knows she has been his lover. Her denials, the passivity of her pleading and his domination only heighten the sexual tension. Finally, as an alternative to consummating their relationship, he kills her – which is also a consummation. The whole thing is deeply fucked up, for want of a better expression.

We were talking earlier about Shakespeare’s implicit stage directions. She says ‘You’re fatal then, / When your eyes roll so’, and later ‘Alas, why gnaw you so your nether lip?’ Shakespeare had a wonderfully acute grasp of human nature, long before Freud. But sometimes he imagined rather caricatured physical reactions.

I don’t think I played either of those.

In the early part of the scene it still feels just possible he might not go through with the murder. But when Desdemona learns that Cassio has been killed, her tears seem to be the catalyst that provokes him. ‘Out, strumpet! Weep’st thou for him to my face?’ After that he just surges into the act of doing it.

I think by then he’s going to kill her anyway. What he imagines is that she will plead her innocence, he will present the evidence, and she will say, I can’t believe you found this out, we were so careful. Then maybe a confession. What he doesn’t envisage is that she would dare to cry for Cassio in front of him. It spins him out. It does bring the moment to fever pitch.

How was the scene physically – how desperately did she react? Did she fight, plead, surrender?

She didn’t fight physically. I think Desdemona always believes there’s a way out, that there’s something she can say that will convince him, that he will see sense. She gets off the bed and moves to a corner of the room, and then I come to that corner and she moves to another, and I come into that corner. She carries on pleading and moving around the space until eventually I catch her and drag her centre-stage and strangle her on ‘It is too late’.

Not on the bed?

Not on the bed, on the floor. And as my fingers close around her throat there’s a kind of sexual possession as well, especially if you go with the theory that they never actually consummated their relationship. Here is the tragic embrace when, in a sense, they finally do it.

A moment after she’s apparently dead he says ‘I would not have thee linger in thy pain. / So, so.’ What happened then?

A pillow.

A pillow over her face?

Yeah.

There’s a description of an eighteenth-century performance in Paris when ‘The killing of Desdemona provoked tears, groans and menaces from all parts of the house. Pretty women fainted and were carried out of the theatre.’ Do you remember anything similar?

Maybe not that extreme!

It must be almost impossible to play the murder of this beautiful woman, whom you adore. As an actor, how on earth do you inhabit it?

It is difficult. Every night you’re doing the worst thing you could ever imagine. And you have all the knowledge, that he has been duped. But I suppose you hang on to what Othello thinks he is killing, which is multilayered. He’s obviously killing the shame and humiliation, but he’s also killing his own insecurities, his sense of failure and worthlessness and of being perceived as second, secondary, or less than. He’s killing racism, he’s killing the Arab slave trade, he’s killing all the things that have interrupted his ability to live. And he is embodying all of those things in this woman who has, in his mind, betrayed him at the deepest level.

What is his mood immediately afterwards? When he says to Emilia ‘’Twas I that kill’d her’, is he defiant, contrite?

It’s extraordinary that the last thing Desdemona says before she dies is that she killed herself. This confuses Othello. Why would she, with her final breath, perjure herself to protect him? I think for the first time he begins to have a modicum of doubt. He suspects something else has happened, and tries to work it out. But what he tells Emilia – ‘She’s like a liar gone to burning hell’ – is barely credible. She’s always been a pious Christian, and in her last moment she tells a lie and is going to be banished to hell.

Montano, Graziano and Iago enter, and Othello hardly speaks a word for seventy lines. When the truth of the handkerchief and Iago’s villainy finally come out, he responds with ‘Are there no stones in heaven / But what serves for the thunder?’ What were you doing during that long beat?

Initially Othello is defiant with Graziano. He’s her uncle and Othello begins, as he planned, to explain the reasons for Desdemona’s death. But then it all falls apart. He realises that Iago has betrayed him, and everything slows down as he processes the information. I think he’s listening intently, trying to take it all in. The moment of shift is when Iago stabs and kills his wife. There is blood and death all around the room. Desdemona is dead on the bed and Emilia’s on the ground, crawling towards her. Iago flees. There’s a sense of his world unravelling, the floodgates opening. It leads into:

Who can control his fate? ’Tis not so now…

Whip me, ye devils,

From the possession of this heavenly sight!

Blow me about in winds! roast me in sulphur!

Wash me in steep-down gulfs of liquid fire.

Then I came back round to hold her on ‘O Desdemon! Dead Desdemona! Dead! O, O!’ It’s almost as if he’s having the five stages of grief right there on stage, in front of us all. He comes through that, and realises what he has done, his life is over and there is an acceptance of death as inevitable.

In his final speech Othello seems calmer, less distraught. He speaks of himself as ‘one that lov’d not wisely, but too well… one not easily jealous, but being wrought, / Perplex’d in the extreme’, which is presumably the way he wants to be remembered after his death. But he’s got a fanciful imagination, and he’s a wonderful storyteller. So is that an accurate summation?

He’s trying to describe truly who he is. He doesn’t want his legacy just to be the guy that killed the girl. He killed her because he loved her, and loved her beyond measure, and therefore became foolish because he had lost his mind to this girl and was able to be manipulated. So he loved her ‘not wisely, but too well’. It’s significant that before he kills himself, Othello evokes the story of Aleppo, and the murder of a Muslim. It is part of his tragedy, I think, that despite all he accomplishes, he is unable to release and let go of his racial hatred. Right up until the end, Othello is haunted by this event, when ‘a turban’d Turk / Beat a Venetian’, and Othello took the Turk by the throat and killed him. And in that moment of trying to release his own demons, and those concerning the Venetian state – that he has given so much to and he feels has completely betrayed him – he evokes this image and kills himself, instead (so to speak) of the Turk. By then in Othello’s rationale the Turk did the right thing to beat a Venetian, because at this point Othello sees the Venetians as completely corrupt. So the irony that he kills himself on that line is profound. And it is what really cements Othello as a play about race, religion, politics. Incredibly well constructed. And I think extraordinarily prescient and relevant to our racial, religious, political understandings in the West. To this day, with bombings in Syria, we are still dealing with the same issues as those in the play. So that last speech is, I think, extraordinary.

How did you kill yourself? Where did the blade come from?

I had a crucifix round my neck. I thought that was in keeping with Othello’s obsession with Christianity. And as a warrior he would have another weapon close by. So I had two weapons, the ‘sword of Spain’ that had been hidden in the bedroom, and a last-resort dagger in the crucifix, which is what I used to stab myself.

Can you summarise Othello’s journey through the play?

I suppose Othello is a kind of beautiful, ornate building, like a palace. It’s extraordinary and fine, and so well looked after. And through the course of the play a gigantic wrecking ball smashes it away until there is absolutely nothing left.

![]()