CHAPTER 2

Calorie Rich, Nutrient Poor

Obesity, Chronic Disease, and the Modern Dietary Dilemma

“It is a hard matter, my fellow citizens, to argue with the belly, since it has no ears.”

—Cato the Elder, Roman senator and historian

For the first time in human history, obesity is a bigger health crisis globally than hunger. More people alive today will suffer disability as a result of consuming excess calories than as a result of consuming too few.1 This stunning fact speaks volumes about the modern dietary dilemma. That’s not to say hunger is no longer an issue in many areas of our planet, but it’s striking that even in the developing world, a growing number of people now suffer the consequences of eating too much of the wrong kinds of food. And this shift has happened within the lifetimes of most people reading this book.

Overfed but undernourished, calorie rich but nutrient poor: this is the deadly paradox that has trapped hundreds of millions of human beings today. In America, where we created many of the eating patterns that are now being exported around the globe, the problem is especially acute. We’ve shared these statistics already, but they bear repeating: 69% of US adults are overweight; 36% are obese.2 17% of children are obese, and 19% have a diet-related chronic condition.3 More than a million Americans die every year from heart disease and cancer, and more than 115 million are diabetic or prediabetic.4

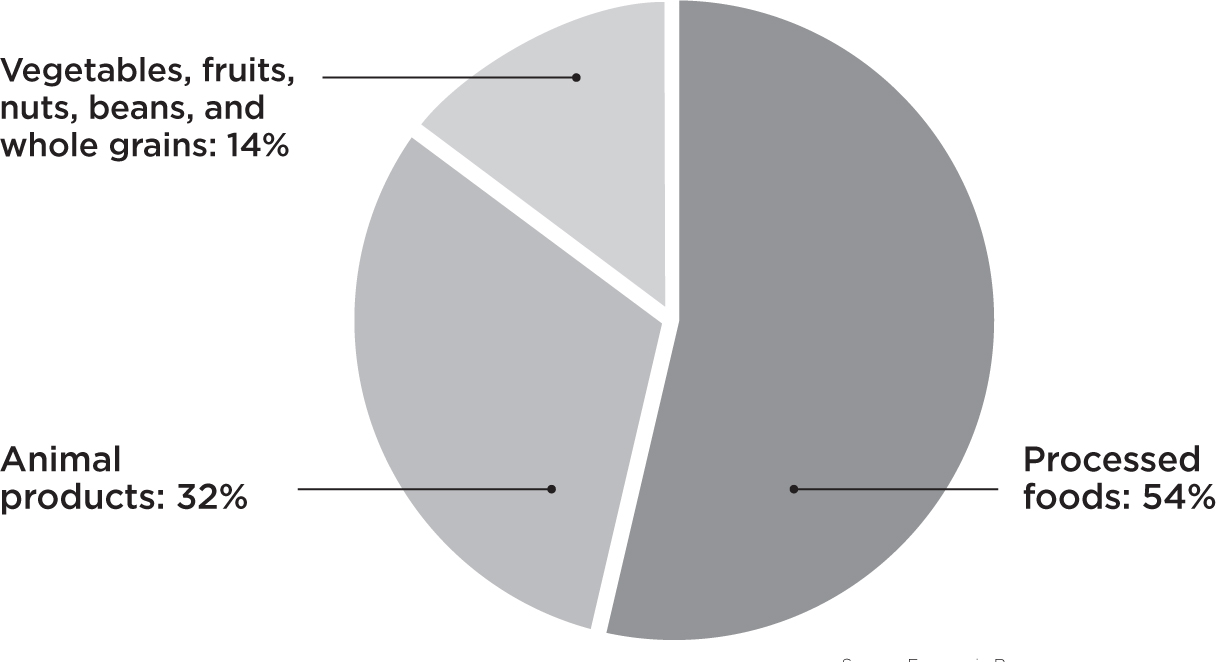

The SAD Truth about American Diets

Since 1970, Americans’ overall daily calorie intake has increased by a shocking 25%.5 Unfortunately, those additional calories haven’t come from healthy vegetables, the consumption of which actually went down by 3% in that time period (and keep in mind that “vegetables” in these surveys include French fries). Instead, the increased calories have come largely from added fats and oils (up 66%), dairy and dairy fats (up 18%), added fruit, largely in the form of fruit juice (up 25%), added sugars (up 10%), and added flour and cereal products (up 42%).6 The Standard American Diet, often referred to by its apt acronym SAD, is not doing us any health favors. The average American gets about 54% of his or her calories from processed foods, 32% from animal products, and a paltry 14% from vegetables, fruits, nuts, beans, and whole grains.7 Those statistics form both a disturbing pie chart and a recipe for chronically poor health.

Source: Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture: Loss-Adjusted Food Availability

As a result of these eating patterns, experts have lamented the fact that the generation being born today will very likely have a lower life expectancy than its parents, a first in American history. And even if life expectancy increases, what will be the quality of those added years? Consider that more people in this country are on prescription drugs than off.8 We live in the age of chronic disease.

All of this bad news runs frustratingly counter to the story that modern medicine once told about its own potential. After all, wasn’t this the institution that cured polio, reduced the infant mortality rate, created vaccines, and saved the lives of millions with antibiotics? Yes, and we all stand on the shoulders of those achievements. But in the last fifty years, the stakes have gone up. Our capacity to grow, process, and distribute food has exploded, while the best nutritional science is still struggling for a foothold in the medical mind. The “take a pill” attitude still dominates the medical and pharmaceutical industries.

Doctors today have little, if any, training in nutrition. “But wait a minute,” the astute reader will say at this point. “Isn’t it true that most deaths in the United States are related to diet and lifestyle?” Yes, and most chronic conditions as well. Surely it would be relevant for doctors to be well informed on that topic. Although medical schools could certainly do more to connect diet and disease, our point here is not to blame them; it is to appreciate the urgency of focusing more on diet and nutrition ourselves. Good information is out there; we just need to seek it out and apply it—in our grocery carts, in our kitchens, and at our dining room tables.

The Problem of Obesity

Human bodies come in all shapes and sizes, and so does beauty. Our intention is not to reinforce any particular social standard of attractiveness—this is a book about health and how what we eat can help us live longer, more vital lives. However, from a health perspective, there is an unavoidable connection between excess weight and a host of chronic conditions that all of us would much rather avoid.

Gaining weight is often the first warning sign that chronic disease is building up under the surface of your body. “Weight sits like a spider at the center of an intricate, tangled web of health and disease,”9 writes Harvard Medical School’s Dr. Willett. Strands in that web include heart disease, strokes, several types of cancer, diabetes, arthritis, and many more unpleasant and sometimes life-threatening conditions.10 Maintaining a healthy body weight is therefore in our best interest if we want to remain vital, active, and glowing with the beauty that good health conveys for decades to come.

This is not to say that a healthy weight is a guarantee of health. If you’re someone who maintains a lean body without much effort, you may think you’re better off, but it’s not necessarily true. You could still have heart disease, diabetes, or cancer developing in your body, even though you don’t yet have a visible warning sign telling you how sick you are. I’m sure you’ve heard stories of the seemingly “thin and healthy” people who are suddenly struck down by diseases for which they didn’t appear to be at risk.

Weight loss is a topic fraught with anxiety for many people. Too many of us have tried to lose weight, succeeded temporarily, and then fallen back. We’ve gone on endless diets, counted calories, controlled our portions, suffered feelings of deprivation, and struggled with the shame and self-hatred that often go with the territory. A whole foods, plant-based diet takes the drama out of downsizing, allowing you to reach and maintain your ideal weight and avoid the negative effects of caloric excess.

Craving Energy: Understanding Calorie Density

Several times a day, we each make the most critical choice we could possibly make for our own health and longevity. We choose to eat certain foods and in so doing we also choose not to eat others. We each have a daily caloric need, based on many factors ranging from our age and activity level to whether we are sick that day or did not eat enough the day before. (Government health recommendations estimate daily caloric needs to be 1,600 to 2,400 for adult women and 2,000 to 3,000 for adult men.) The type of calories we choose to consume to meet this need is up to us in any given moment.

So what is a calorie? A calorie is a measure of the energy contained in food. We all expend a certain amount of energy each day in order for our bodies to perform their functions. If we do any kind of physical exercise, manual labor, or other activity, we expend some more. The food we eat is a fuel source that provides us with that energy. Calories come in three forms: carbohydrates, fat, and protein. If we consume more energy than we expend, the body will store the excess energy in the form of fat and we will gain weight. If we consume less, our bodies will need other sources of fuel, burning stored fat and leading to weight loss.

Different types of food contain vastly different amounts of calories relative to their weights. If you take one pound of lettuce and compare it to one pound of cheese, for example, the lettuce has far fewer calories than the cheese. The cheese, therefore, is more “calorie dense.”

For hundreds of thousands of years, the main problem human beings and their evolutionary predecessors faced was getting enough calories to stay alive. The less time we spent gathering food the better, because that reduced the risk of falling prey to wild animals. Therefore, we evolved to seek out the foods that would give us more calories to less bulk; in other words, the most calorie-dense foods (see chapter 11 for more on why). Cheese wasn’t on the menu back in our hunter-gatherer days, but our ancestors would have been drawn to the more calorie-dense fruits and vegetables—for example, they might have chosen wild nuts over wild greens. And when they could get it, the occasional piece of wild lean meat would have been attractive.

This equation worked fairly well for most of human history. As long as we were choosing between whole plant foods, with the occasional addition of lean meat, our attraction to the most calorie-dense options did not present a problem when it came to maintaining a healthy weight. Indeed, it was essential for staying alive. Of course, the less-calorie-dense foods contain important nutrients, and evolution has ensured that their variety of delicious tastes and textures keeps us coming back for those as well. But there was little chance of our eating too many calories, because the amount of bulk we needed to consume in order to meet our needs would fill us up.

The Feeling of Fullness: Understanding Satiety

Weight loss gurus are fond of reducing the process to a simple formula: calories in < calories out. So long as you consume fewer calories than you expend, you’ll lose weight. Makes sense, in theory. But in order to make this formula work for you in practice, you need to understand that not all calories are created equal when it comes to filling you up. Some come in the form of fiber-rich, nutrient-rich foods that will leave you feeling full and satisfied. Others come in the form of refined, fiber-stripped, highly processed foods that contain few or no nutrients and will leave you hungry, making you more likely to eat more. A chicken nugget is so calorie dense that after eating only two, you’ve consumed a hundred calories, the equivalent of a whole bowl of lentil soup (one and a quarter cups). And who stops at two chicken nuggets? You’ll probably want to eat at least ten, or twelve, taking in five or six hundred calories very quickly. With the lentil soup, by comparison, you’ll probably feel full after just one bowl, or maybe two. To lose weight, or to maintain a healthy weight, the key is to choose foods that give you adequate calories but not too many, while making you feel full so that you’re less likely to overeat.

There’s a term for the feeling of fullness: satiety. It’s a physical sensation that is the opposite of hunger. Just as hunger is the body’s mechanism for telling you to eat, satiety is the body’s mechanism for telling you to stop. Unfortunately, food processing has wreaked havoc with these instincts so that many of us can no longer trust the signals our bodies are giving us. As long as we are eating highly processed, refined foods, we are likely to feel hungry even when we’ve eaten more calories than we need, and we won’t experience satiety until we’ve overeaten.

Here’s what we know about how satiety works. There are “receptors” in the stomach and digestive tract that measure the food we ingest in several ways. One thing they measure is the weight and bulk of the food, or the amount of “stretch” that occurs in the stomach to make room for the food. This is why foods containing a lot of fiber fill us up more—they take up more space and trigger a signal to the brain that says enough has been eaten. Foods that have been refined and processed (with fiber and water removed) take up less space, so even though they contain more calories, the message does not get back to your brain that you’ve had enough.

You also have “receptors” that ensure you are consuming calories and not just getting stretch without caloric content. When you’re eating whole plant foods, these tend to work quite accurately, together with the stretch receptors, to ensure that you get the right amount of food and not too much. Over the last few decades, however, the rise of processed food has fundamentally altered this algorithm. Processing tends to increase the calorie density of any given food by:

As we alter our food in this way, its bulk/weight decreases (because of the removal of fiber and water) and the number of calories increases (due to added fat and/or sugar). Hence the number of calories relative to weight increases dramatically. For example, corn, which contains 500 calories per pound, becomes corn oil, at 4,000 calories per pound. A sweet potato, which weighs in at 389 calories per pound, gets cut up and deep-fried in that oil to become sweet potato chips, at 2,400 calories per pound. Beets, at just 200 calories per pound, become refined sugar, at 1,800 calories per pound.

When you eat these unnaturally concentrated foods, your calorie receptors and stretch receptors no longer correlate. You’re getting a lot of calories, but very little bulk. With its two measurement systems out of sync, your body is confused. The message that goes back to the brain reads something like this: “I think we got enough calories, but maybe I am wrong, because I don’t feel full.” So we eat more to fill our stomachs, and in the process we overconsume calories. The problem gets exaggerated when the calories come in liquid form, as with oils, juices, or sugary drinks, which stretch the stomach barely if at all, but contain a lot of calories. This is why one of the most important pieces of weight-loss advice you’ll ever hear is, Don’t drink your calories!

Those extra calories accumulate over time. Three thousand five hundred additional calories equals one additional pound of fat, so if you overshoot your needs by as little as one hundred calories a meal (two chicken nuggets) and you do this three times a day, you will gain a pound of fat every two weeks, which adds up to more than twenty-five pounds in a year.

It’s not only processed foods that mess with our satiety signals. Animal foods also lack fiber while being calorie dense. Today’s factory-farmed, grain-fed animals bear little resemblance to the lean wild game that our ancestors might have feasted on after an occasional hunt. When we eat their meats, cooked in oil, alongside other calorie-dense, fiber-deficient foods like white bread, fries, ketchup, and so on, it’s a recipe for obesity.

Now that these foods are part of our everyday menu of choices, our evolutionary propensity to choose the most calorie-dense options has become a problem. We are no longer choosing between lettuce and a banana; we are choosing between a banana and a burger, and the evolutionary mechanism that kept our ancestors well fueled is leading us down a dangerous path.

When we choose the burger, and pair it with an order of fries and a soda, we get more than a thousand calories in a single sitting. Fast food is not just ready in minutes—it’s eaten and digested equally quickly because it has already been refined and broken down, requiring astonishingly little effort to consume.

Why Diets Don’t Work

Once you understand the basic principles of calorie density and satiety, you can start to make sense of why so many people find their weight creeping up. It also clarifies why dieting, which relies on portion control and calorie restriction, rarely works. It’s not because you lack self-control or willpower; it’s because the environment in which you live is making foods available to you that subvert your body’s natural instincts and trick you into feeling hungry when you’ve already consumed more calories than you need.

Hunger is a powerful survival mechanism, and it is very hard to defeat it through willpower alone. After all, your brain thinks that the lack of stretch means you are actually calorie deficient and starving, so it continues sending hunger signals in an attempt to keep you alive. Sooner or later you’re likely to respond to it by eating more.

The good news is that by choosing whole foods, mostly plants, you can begin to trust your own body again. You won’t have to obsessively monitor your portion sizes or deny your hunger; in fact, you may have to retrain yourself to eat larger meals than you are accustomed to if you have been in the habit of controlling portions to manage your weight. These are the foods your body thrives on, and they also happen to be the foods that your body can measure accurately, because they correlate calorie density and stretch. Your satiety signals will become more trustworthy as you choose foods that are naturally nutritious and filling.

Eating whole foods, mostly plants, is a great recipe for sustained weight loss because they combine high fiber and water content with low calorie density. However, for it to work, you need to make sure you eat enough. That’s right, eat enough! This is not a diet of portion control or deprivation. If you choose only the foods that are lowest in calorie density, you’ll continue to feel hungry. Therefore, it’s important to also eat highly satiating plant foods like starchy vegetables (yams, squash, corn, potatoes, and so on), whole grains (rice, wheat, oats, and so on), and legumes (beans, peas, lentils, and so on) to ensure that you meet your energy needs without having to consume mountains of food to simply get enough calories. Combining fresh vegetables and fruits with whole grains, legumes, and starchy vegetables is the best mix to ensure that you’ll feel full and lose excess weight.

Studies have confirmed the important relationships between calorie density, satiety, and overconsumption. Subjects in these studies are divided into two groups, one eating a calorie-dense diet and the other eating a less calorie-dense diet. They are allowed to eat when hungry until they are full. The results are clear: those fed high-calorie-density diets tend to take in more calories and gain weight, while those fed lower-calorie-density diets tend to take in fewer calories (even though they consume more bulk) and lose weight. One such study concluded, “Our findings support the hypothesis that a relation exists between the consumption of an energy-dense diet and obesity and provide evidence of the importance of fruit and vegetable consumption for weight management.”11

Choose a whole foods, plant-based diet, and you will quickly be on your way toward reaching and maintaining your ideal weight. However, this is not simply a weight-loss book, and the Whole Foods Diet offers much more than a trim waist. Our goal is to help you learn to eat for optimum health and use diet to prevent or reverse disease. In order to do this, there is another key principle you need to understand.

Nutrient Density: Making Every Calorie Count

The concept of “nutrient density” has been reinvented and popularized by Joel Fuhrman, MD, one of the most important thinkers and practitioners in modern nutrition, and it is at the heart of his popular “Nutritarian” approach to eating (not to be confused with Pollan’s “nutritionism,” discussed here). Dr. Fuhrman explains this idea with a formula:

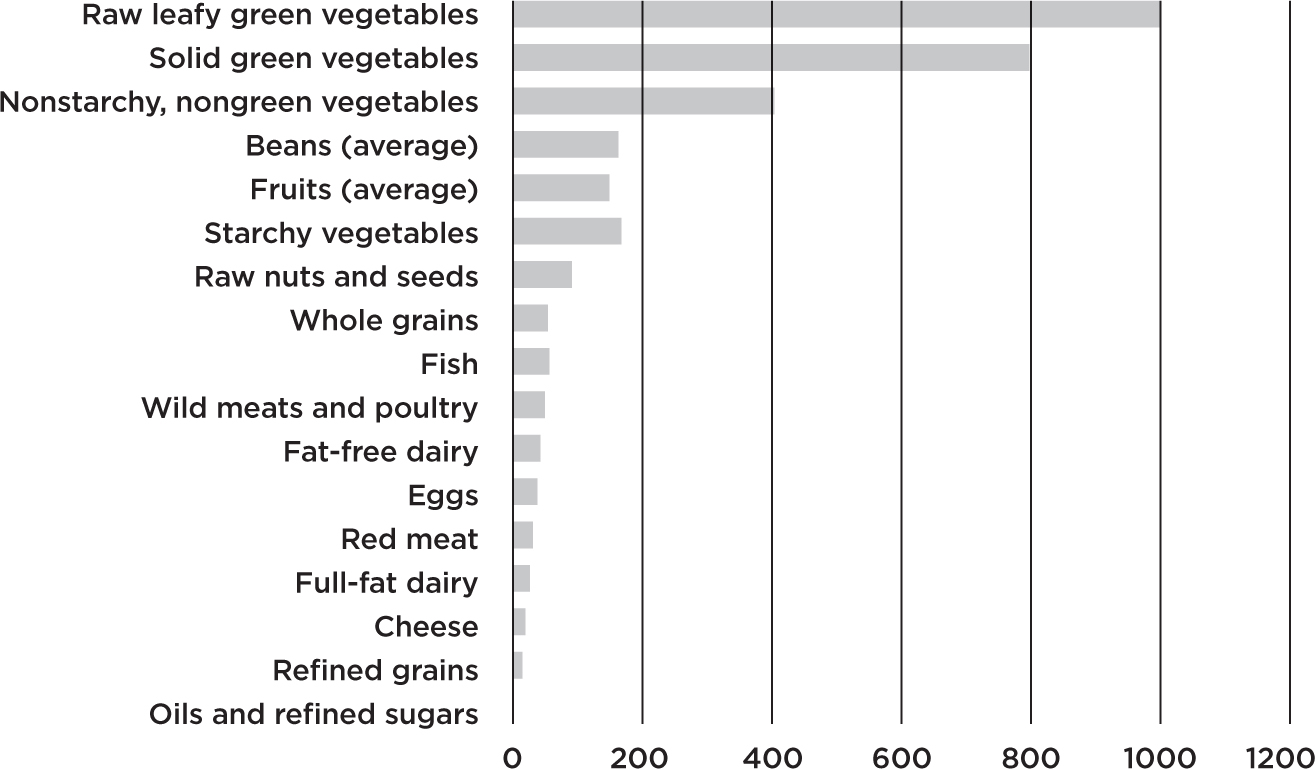

In other words, to be healthy, you need to choose foods that grant you a favorable amount of nutrients per calorie. That’s what nutrient dense means. When Fuhrman talks about nutrients, he’s not referring to the macronutrients—protein, fats, and carbohydrates—the elements in our food that deliver calories. He’s referring to what he calls “noncaloric food factors,” or micronutrients—including vitamins, minerals, fiber, and phytochemicals. Some foods contain a lot of calories but few or even no nutrients, in this sense. Fuhrman’s approach to eating is to “make every calorie count”13 by striving to get an adequate amount and diversity of micronutrients from our food every day.

This may sound like a commonsense idea, but it leads to quite a radical reevaluation of foods. If you were to ask the average American what foods contain the most nutrients, he or she would probably rank meats like beef and chicken pretty high, having been raised to consider “protein” the most important element of nutrition. And yet by Fuhrman’s measure, leafy greens like kale and romaine far outrank meats on the nutrient density scale. Have you ever wondered why kale suddenly became such a popular health food a few years back? It was partly due to Fuhrman, who awarded this rather tough leafy green the top score in his ANDI (Aggregate Nutrient Density Index) system for measuring nutrient density, a perfect 1,000. When Whole Foods Market started using his system in stores, sales of kale skyrocketed. Kale (like other dark green leafy cruciferous vegetables) is packed with phytochemicals and fiber but low in calories; hence it has an extraordinarily high ratio of nutrients to calories. As Fuhrman is fond of pointing out, in his lectures and often on his T-shirt, “Kale is the new beef!”

Dr. Fuhrman is outspoken about the misinformation that runs rampant in the diet world. One topic he’s particularly passionate about is metabolism. “Nutritional scientists the world over recognize that excess calories reduce our life span, while lower caloric intake extends life span,” he declares. “And yet people all over America are trying to use fads and tricks to speed up their metabolic rates so they can eat more calories without getting fat. That doesn’t make any sense! By speeding up your metabolism, you’re aging yourself!”14

Dr. Fuhrman’s Aggregate Nutrient Density Index (ANDI)

Fuhrman’s concept of nutrient density is a powerful tool for shifting your focus away from what you shouldn’t eat and toward all the wonderful foods you should eat in order to maximize your nutrients. But before you rush out armed with an ANDI chart to start measuring one vegetable against another, it’s important to understand that compared to processed foods and animal foods, all natural plant foods are nutrient dense. The most important thing is that you eat plenty of them, and if broccoli doesn’t score quite as high as collard greens, that’s no reason to stop eating it. If you simply eat a whole foods, plant-based diet and include a wide variety of fruits and vegetables, you will naturally be getting a much higher amount of nutrients per calorie than anyone who eats a diet heavy in processed foods and animal foods.

Don’t pass over the plant foods that rank lower on the ANDI scale, like nuts, seeds, starchy vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and fresh fruit. These still contain plenty of beneficial nutrients. Dr. Fuhrman does not recommend a diet of only eating the highest ANDI scoring foods such as leafy greens. These foods are important to include, but he also recommends a diversity of other plant foods for excellent health, protection against cancer, and longevity. In fact, fruits, beans, and seeds are an important part of his healthful program.

Nutrient density. Calorie density. Satiety. These are all critical concepts to understand, enabling you to choose foods that ensure you’ll be well nourished and well satisfied.

WHOLE FOODIE TAKEAWAYS

WHOLE FOODIE TAKEAWAYS

• Understand calorie density—Human beings have an evolutionary predilection to seek out the most calorie-dense foods. Highly processed foods are extremely calorie dense but lack the bulk to stretch the stomach, therefore confusing the body’s natural systems to know when to stop eating. Choose fiber-rich whole plant foods and you can trust your body to tell you when you’ve had enough.

• Eat a variety of fruits and veggies—Plant foods are packed with health-promoting, disease-fighting nutrients. Per calorie, they are far more nutrient dense than animal foods. Eat lots of different fruits and vegetables, as well as legumes and whole grains, to maximize these benefits.