Raising rabbits is gaining in popularity for many reasons. For example, rabbits can be raised in any type of environment, whether it be country, suburb, or city, and they fit easily into most family settings. A rabbit makes a friendly, low-maintenance family pet and is a good size animal for children as well as adults to care for. In addition, it doesn’t take a lot of money to get started with rabbits — this project will fit into most family budgets. Although proper equipment contributes to the success of raising rabbits, it is more important for equipment to be functional than fancy.

There is an unusually broad range of choices for rabbits. Much depends on whether you want a pet or a wool business. Also influencing your choice may be:

• Availability. Is your chosen breed raised in your area? If you select a breed that is popular locally, you will have a greater choice of quality animals.

• Cost of animal. You will find that some breeds command higher prices than others.

• Cost of care. Other factors, such as breed size, also affect overall costs, since larger breeds need larger housing and consume more feed.

• Amount of care. Angoras, which must be groomed daily, take more time than do other breeds.

• Ease of raising. Some breeds, such as Netherland Dwarfs and Holland Lops, can be difficult to raise.

After you have evaluated your own needs and preferences, you’ll want to select a breed, locate breeders with stock for sale, and then visit a rabbitry to choose your rabbit.

An increasing number of people keep rabbits as pets. As pets, rabbits can be kept indoors or out, they make no noise, they have few veterinary needs (including no vaccination), their initial cost is low, and daily care is not demanding. These features make rabbits ideal pets for busy, modern families. Any breed may be kept as a pet, but if you want to raise rabbits primarily to sell as pets, you are wise to consider some of the smaller breeds. These include: Netherland Dwarf, Dutch, Mini Lop, and Holland Lop.

In recent years, natural fibers and handcrafted items have become very popular. This has brought about a new appreciation for the Angora rabbit breeds. Soft and warm, Angora wool is obtained by pulling the loose hair from the mature coat. Because you are really just helping the natural shedding process, this hand plucking does not hurt the animal. The plucked wool can then be spun into yarn. Although Angora rabbits require some special management (they need to be groomed often), raising them and selling their wool is an excellent business venture.

Whether you are looking for a pet or want to start a small rabbit business, you may want to begin with one rabbit. This allows you to experience both the fun and the work that goes with rabbit ownership. If you enjoy caring for one rabbit, you can get more rabbits as time goes on.

Some new rabbit owners who intend to start a breeding program choose to start with more than one. A reasonable number to begin with is three rabbits, consisting of one buck (male) and two does (female), known as a trio. Ask the breeder to help you select three rabbits that are not too closely related. Look at the animals’ pedigrees. The rabbits in your trio may have some relatives in common, but their pedigrees should show some differences in their family trees as well. Your trio should not be brother and sisters. Three rabbits from the same litter are too closely related to be used for breeding purposes.

Whatever number of rabbits you begin with, remember that each rabbit will need its own cage. Don’t purchase more animals than you are able to care for properly.

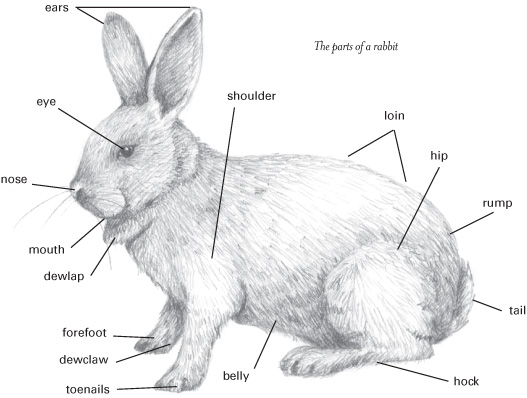

Good health is the most important quality to consider when you select your stock. Look for the following features to determine a healthy rabbit.

• Eyes. The eyes are bright, with no discharge and no spots or cloudiness.

• Ears. The ears look clean inside. A brown, crusty appearance could indicate ear mites.

• Nose. The nose is clean and dry, with no discharge that might indicate a cold.

• Front feet. These are clean. A crusty matting on the inside of the front paws indicates that the rabbit has been wiping a runny nose, and thus may have a cold.

• Hind feet. The bottoms of the hind feet are well furred. Bare or sore-looking spots can indicate the beginning of sore hocks.

• Teeth. The front teeth line up correctly, with the front top two teeth slightly overlapping the bottom ones.

• General condition. The rabbit’s fur is clean. Its body feels smooth and firm, not bony.

• Rear end. The area at the base of the rabbit’s tail should be clean, with no manure sticking to the fur.

A new rabbit has many adjustments to make. Give your rabbit a few days to get used to you and its new surroundings before you handle it a lot.

Get to know your rabbit in a setting where both of you can be comfortable. A good place to get acquainted is at a picnic table covered with a rug, towel, or some other covering that will give the rabbit secure, not slippery, footing. Your rabbit will be able to move around safely on the table, and you can safely visit and pet your rabbit without having to lift it. Rabbits will usually not jump off a table. In spite of this, never leave a rabbit unattended when it is out of its cage.

Once your rabbit seems comfortable on the table, practice picking it up. Because the table offers a handy surface to set the rabbit safely back onto, this setting is much better than risking a possible fall to the ground.

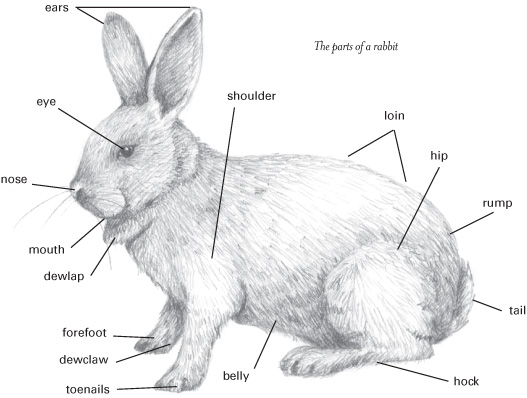

A “football hold” is a secure way to carry your rabbit.

The best way to pick up a rabbit is to place one hand under it, just behind its front legs. Place your other hand under the animal’s rump. Lift with the hand that is by the front legs and support the animal’s weight with your other hand. Place the animal next to your body, with its head directed toward the corner formed by your elbow. Your lifting arm and your body now support the rabbit – just like tucking a football against you. Your other hand is free and can rest on the rabbit’s back for extra security. Place the animal gently back on the table and repeat this lift.

To help your rabbit become comfortable with being carried, practice handling skills often, but for short periods of time — 10 to 15 minutes at a stretch.

Sometimes an overactive or frightened bunny will struggle and get out of control. When this happens, drop to one knee as you work to quiet your animal. Lowering yourself to one knee lessens the distance the rabbit has to fall and provides a more secure base for a frightened rabbit. You can also easily set the animal on the ground from this position, if necessary. After it’s had a short rest on the ground, carefully and securely lift the rabbit again. Even the most mild-mannered rabbit can have a bad day, so be prepared to handle any situation in a calm, controlled manner.

If your rabbit starts to struggle while you are holding it, drop to one knee.

After you master lifting and carrying your rabbit, you will want to learn how to turn it over; you’ll need to get it in this position in order to better observe its teeth, its toenails, and its sex. You can’t see everything about a rabbit just by looking at the top!

Turning a rabbit over puts the animal into a very unnatural position. First, its feet are off the ground so it cannot run away, and second, to make matters worse from its point of view, its underside is now exposed. A wild rabbit in this position is probably one that is about to be eaten by a predator! Your rabbit has good reason to resist this type of handling, so be especially careful and patient.

Practice turning your rabbit over back at the table where you first learned how to lift and carry it. Again, you will want a rug on the table, and wear a long-sleeved shirt.

To turn the rabbit, use one hand to control the head and the other hand to control and support the hindquarters. Place the hand that holds the rabbit’s head so that you are folding its ears down against its back, while you reach around the base of the head. If you prefer, you can place your index finger between the base of the rabbit’s ears and then wrap your other fingers around toward its jaw. With your other hand, cradle the rump. Now that your hands are in place, lift with the hand that is on the head and at the same time roll the animal’s hindquarters toward you. Try to do this movement in a smooth, unhurried manner.

If your rabbit cooperated, you will now be able to let the table support its hindquarters. This will free the hand that was holding the rump to check other things, such as the teeth and toenails. If your rabbit fights against this procedure, it is showing you that this is not its first choice of positions. Keep trying, but be sure to do so in a place where the rabbit hasn’t far to fall, and try to support it securely. Your rabbit can injure itself if it struggles and falls.

If you need to turn your rabbit over for a closer look and no table is handy, let the animal rest on your forearm instead of on the table. When you have the rabbit in this position, you get better control over the hindquarters, because they are tucked between your elbow and your body. This is even easier if you sit in a chair; you can then use your legs instead of the table to support your rabbit. In fact, you may find that when you are seated, you can hold your rabbit more securely for grooming and toenail trimming.

When turning your rabbit over, use one hand to control and support the head and the other hand to control and support the hindquarters.

Rabbit housing – called a hutch – can be the largest single expense in your rabbit project. Whether you buy or build, you must be sure that your housing – and the environment in which you place it – meets the rabbit’s needs. Proper housing contributes greatly to the health and happiness of your animals.

Your rabbit will spend most of its time in its hutch; the hutch should be large enough for the rabbit to move around in, as well as for feeding equipment. When planning how much space you need, the general rule is to allow 1 square foot (0.1 m2) of space for each pound your rabbit weighs. A cage that is 2 feet (60 cm) wide and 3 feet (90 cm) long is 6 square feet (0.6 m2) and would be perfect for a 6-pound (2.7 kg) Mini Lop. Find out how much a mature animal of your rabbit’s breed weighs, and use this as a guide to plan the size of its hutch. Young rabbits and bucks may do fine with slightly less space, but does that will be having litters (baby bunnies) will need the whole amount.

After you have figured the width and length of the cage, you must decide how high it should be. Most cages are 18 inches (45 cm) high, although small breeds, like the Netherland Dwarf, need a height of only 12 to 14 inches (30-35 cm).

Many people who own multiple rabbits keep their rabbitries outdoors. With proper care, rabbits have fewer health problems when raised outdoors and can survive temperatures well below zero. However, you do need to provide protection from winds, rain, and snow. If your cages are inside, you are already providing this protection. If your cages are outside, you will want to add protection as the temperature drops. Most outdoor cages can be enclosed quite easily by stapling plastic sheeting around three sides. If you live where the weather is extremely cold, cover the front with a flap of plastic as well. Do not enclose the whole cage so tightly that the ventilation is poor or that it is difficult to get in to feed and care for your animal.

Take advantage of the winter sun. If your outside cages are movable, place them in a location that receives a lot of direct sun.

Although healthy adult rabbits don’t suffer when it is cold, newborn rabbits can easily die from the cold. If you are expecting a litter during cold weather, be sure the doe has a well-bedded nest box. You may want to move the doe into a warmer location, such as a cellar or garage. After the litter is about 10 days old, the cage, with Mom and her nest box of babies, can be moved back outside.

Rabbits are most comfortable when the temperatures are between 50° and 69°F (10° and 20°C). In hot climates, it is important to locate the cage in the shade, and ensure that the cage has lots of air circulation around it. Also provide plenty of cool, fresh water.

In extreme heat, use empty plastic soda bottles to make rabbit coolers. Fill the bottles two-thirds to three-quarters full with water and keep them in your freezer. In periods of extreme heat, lay a frozen bottle in each cage. The rabbits will beat the heat when they stretch out alongside their rabbit cooler.

Wrap plastic sheeting around three sides of your hutch, and nail a separate flap of plastic over the front.

A sturdy, well-built hutch will contribute to the safety of your rabbits. Most cages are built on legs or hung above the ground – which also makes the cages safer from dogs, cats, rodents, raccoons, and opossums. Keeping your cages in a fenced area or indoors offers even better protection, but this may be impossible when you are just getting started.

Clean cages are important to the health of your rabbits. If your cages are easy to clean, you will be able to do a better job of caring for your rabbits. Cages should have a wire floor that allows droppings to fall through to a tray or to the ground. Choose all-wire cages or wood-framed cages that do not have areas where manure can pile up. Plan your cages so you can easily reach into them and get around them to clean all parts

Providing proper feed for your rabbits is a very important part of successful rabbit raising. A healthy, balanced diet is based on providing commercial rabbit pellets and fresh water. In the past, rabbit owners had to mix different feeds in order to get the proper nutritional balance for their animals. Nowadays, stores carry feed that is already balanced. Commercial pellets are the best and easiest way to provide proper nutrition for your rabbits. However, commercial feeds do vary, and different feeds are available in different locations. Talk with other breeders and with your feed store clerk to learn about the brands available in your area.

You’ll also learn that even under the same brand name there are often several different types of feed. These types of feed are designed to meet the needs of different rabbits at different stages in their lives. The feed ingredient that varies is the protein content. Mature animals usually need a feed that provides 15 to 16 percent protein. Young growing animals and active breeding does are often fed a ration with a higher level of protein, 17 to 18 percent.

The U.S. government requires that all rabbit feed contain at least a certain amount of protein and fat. A feed may contain more than these amounts, but not less. The amount of protein and fat is listed on the feed package. The package also lists the fiber content. A package label may say that the feed has no more than 18 or 20 percent fiber, but this tells you only the maximum amount of fiber. You also need to know the minimum amount it contains. It is very important that rabbits eat feed containing at least 16 percent fiber. If they get less than that, they may have diarrhea.

No matter which type of feed you provide, your rabbits will not eat well unless you provide the most important nutrient of all – water! We often do not think of water as food, but it is essential to your rabbits’ health. Rabbits simply do not thrive without a constant supply of clean water.

Salt is another ingredient that is important to a balanced feed. It is not necessary to provide a salt spool for your rabbit (and they cause your cage to rust, as well). You may see advertisements for inexpensive salt spools that can be hung in each cage, but the commercial pellets you use as feed already include enough salt to meet your rabbit’s needs.

Many owners also feed hay to their rabbits. Feeding hay will add more time to your feeding and cleaning chores, but rabbits enjoy good-quality hay, and it adds extra fiber to their diet. If you feed hay, be sure it smells good, is not dusty, and is not moldy.

If you choose to feed hay on a regular basis, you will want hay mangers in each cage. Hay mangers are easy to construct from scraps of 1” × 2” (2.5 cm × 5 cm) wire. If you make your own cage, you can use the leftover wire. If your cages are indoors and are of all-wire construction, you can just place a handful of hay on the top and the rabbits will reach up and pull it through the wire. Avoid setting hay inside on the floor of the cage, because it will soon become soiled and droppings will collect on it. This can cause disease and parasite problems.

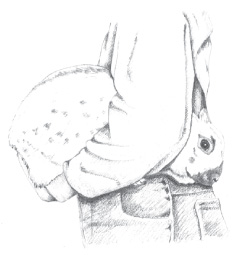

To make a simple hayrack, bend a scrap of wire and attach it to the side of your cage with J-clips.

If we study the feeding habits of wild rabbits, we can apply what we learn to feeding our domestic rabbits. In nature, rabbits have learned to stay in a safe place during the day. In late afternoon, hungry wild rabbits come out of hiding. By this time, they are ready for their big meal of the day. Wild rabbits are nocturnal animals, active throughout the night and into the early-morning hours.

If our tame rabbits could pick a mealtime, they would probably agree with their wild relatives and choose late afternoon. Using this information, most rabbit breeders feed the largest portion of their rabbits’ daily ration in the late afternoon or early evening.

How often should your rabbits be fed? Although different breeders develop a schedule that works for them, two feedings a day – one in the morning and one in the late afternoon – seem to be most common. If you choose to feed twice a day, serve a lesser portion in the morning than in the afternoon.

If you have self-feeders and water bottles, you may feel comfortable feeding only once a day. Feeding time, however, is for more than just feeding. Time spent with your rabbits is an opportunity for discovering situations such as:

• Has a youngster fallen out of the nest box?

• Is an animal sick or not eating well?

• Does a cage need a simple repair before it becomes a major repair?

• Does your rabbit need extra water due to extreme heat or freezing conditions? Remember that the overall health of your rabbit will be better if clean, fresh water is available at all times.

Because a lot can happen to your rabbits in a 24-hour period, you should feed, water, and observe your animals at least twice a day. The serious rabbit breeder will see this as a worthwhile investment in time.

Whatever feeding schedule you choose, remember that it is very important to follow the same schedule every day. Your rabbits depend upon you, and they will settle into the schedule that you set. Avoid variation in feeding times. If you regularly feed at 7 A.M, you should do so even if it’s Saturday and you want to stay in bed a little longer. Plan ahead for times when you cannot be there to feed your rabbits. Be sure other family members are familiar with your feeding program so that they can help out from time to time. If your family includes more than one rabbit raiser, you can take turns with feeding responsibilities.

There is no set amount of feed that is right for all rabbits, but the following chart gives you some average amounts.

In order to use this chart, you need a simple way to measure how much to feed each animal. You can make your own measuring container from empty cans. For example, a 6-ounce tuna fish can filled level to the top holds 4 ounces of pellets. The same can filled so that the pellets form a small mound above the lid gives a 5-ounce serving. You may use a larger can and mark several different levels to indicate the amounts you most commonly feed.

Feed guidelines are exactly what their name says, guidelines only. As you get to know your rabbits better, you will find that some need more feed and some need less. A simple way to judge who need more or less is to feel your rabbits regularly. Just a few pats can give you an idea of their condition. If you stroke each rabbit from the base of its head and follow along the backbone, you will soon learn to tell who is too fat and who is too thin. When you run your hand over the rabbit, you will feel the backbone below the fur and muscles. As you feel the bumps of the individual bones that make up the backbone, they should feel rounded. If the bumps feel sharp or pointed, your rabbit can use an increase in feed. (Note: Extreme thinness may also indicate health problems.) If you don’t feel the individual bumps, it probably means there is too much fat covering them, so that rabbit will do better on less feed.

Stroke your rabbit along its backbone regularly to judge whether it is getting the proper amount of food. The bumps of the individual bones that make up the backbone should feel rounded.

If you need to adjust the feed amount, make the change gradually, not all at once. Unless the rabbit is extremely thin or extremely fat, increase or decrease by about 1 ounce each day. A small plastic scoop that is used to measure ground coffee holds about 1 ounce of pellets. Use this scoop to add or subtract feed, 1 ounce at a time. It will take awhile for the change to show on your rabbit, but you should see and feel a difference in 1 to 2 weeks. It’s good to get in the habit of giving each rabbit a weekly check. It takes only a few seconds to feel down the back of an animal. If you check regularly, you will be able to adjust feed before your rabbit becomes extremely fat or thin.

In general, overfeeding is a more common problem than underfeeding. For one thing, overfeeding means it costs you more to care for your rabbits. In addition, if you are breeding your rabbits, you’ll find that overweight rabbits are generally less productive than animals of the proper weight. In fact, fat rabbits often do not breed, and an overweight doe that does become pregnant can often develop problems.

A good schedule will allow you to use your time effectively to accomplish the many tasks that are part of raising healthy rabbits. The chores that are required can be broken down into daily, weekly, and monthly tasks.

• Feed and water regularly. Establish a daily schedule and stick with it 7 days a week.

• Observe your rabbits and their environment. Daily observation helps you catch small problems before they become large problems.

• Keep things clean. Attend to small cleaning needs so they don’t grow into large cleaning chores.

• Handle your rabbits. Regular handling will make your animals more gentle, and you will become more aware of their individual condition. This may be impractical in a large rabbitry, but you should strive to handle some of your animals each day.

• Clean cages. Solid-bottom cages and cages with pullout trays must be cleaned and re-bedded weekly. On wire-bottom cages, use a wire brush to remove any buildup of manure or fur.

• Clean feeders. Rinse crocks with water-and-chlorine-bleach solution (1 part household bleach to 5 parts water). Check self-feeders for clogs of spoiled feed.

• Check rabbits’ health. If there are animals that you did not have time to handle and check earlier in the week, do so now.

• Check supplies. Do you have enough feed and bedding for the coming week?

• Make necessary repairs. Have you noticed a loose door latch or a small hole in the wire flooring? Take time to do these small repairs before they lead to larger problems.

• Check toenails. You will not have to trim the toenails of every rabbit every month, but you should check each animal and trim those that need it. This is an important management skill to learn, because properly trimmed toenails decrease the chances of your rabbit being injured. Long toenails can get caught in the cage wire and cause broken toes and missing toenails. The time spent trimming toenails will also benefit you; you will be less likely to be scratched when you handle your rabbit.

Trimming toenails is usually a two-person job. With someone holding the rabbit on its back, use one hand to push back the fur so that you can see the nail and the other hand to do the trimming. Trim just the tip of the nail, not the more dense portion, which contains blood vessels.

The equipment you need to build and outfit a rabbitry is quite limited: hutches, feeders, waterers, and nest boxes. Essential hand tools to build the rabbitry are also few; most households have all but one or two. No power tools are required; nor do you need a large outlay of cash or time. You can construct and outfit your rabbitry as both allow. Interruptions to the construction process will present no problem – you can drop the work and resume it at any point. You can build indoors or out; the materials make no dust or dirt and require no loud banging or sawing. Everything is quite clean and quiet. And simple. If you follow the instructions, your very first efforts will produce a product that functions as well and looks as good as any built by experienced professionals.

Successful rabbit raisers consider no other materials for a rabbit hutch than wire and metal. Among other activities, rabbits gnaw and urinate, so you can dismiss wood immediately. If you use wood, they will eat some of it and foul the rest of it. Wire and metal cost less than lumber; no expensive hinges or other hardware are required.

If you need only one or two hutches, perhaps for pet rabbits, buy them from your local farm supply store or send away to a supplier. That’s because the welded wire fabric you need is expensive in small quantities (if it is available at all), and it will be cheaper for you to buy one or two than to build them.

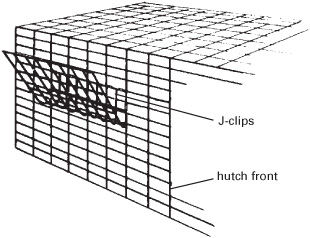

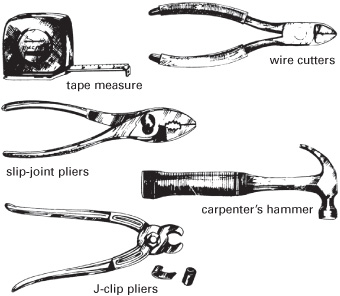

To build your own, here are the tools and materials you will need.

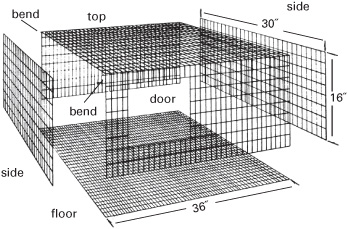

The basic all-wire hutch. Front, top, back, and sides are 1” × 2” wire. Floor is ½” × 1” wire. Door is positioned off center to allow a feeder and waterer at right.

Tools

One pair of heavy-duty, 7” or 8” wire-cutting pliers, preferably with flush-cutting jaws.

One pair of ordinary slip-joint pliers.

One tape measure, preferably retractable steel. A 12’ tape is best but a shorter one will do.

An ordinary carpenter’s hammer.

One pair of special J-clip pliers, available from your farm supply store.

A short length of 2 × 4 lumber; about 3’ long is fine.

Materials

A supply of 1” × 2” welded wire fencing, 14 gauge, sometimes called turkey wire. Dimensions will vary as described below.

A supply of ½” × 1” welded wire, 14 or 16 gauge, with variable dimensions as described below.

A supply of J-clips, available where you obtain the J-clip pliers.

A door latch for each hutch.

A door hanger for each hutch.

Before we actually start hutch construction, let’s discuss the tools and materials for a good understanding of what is involved.

Materials for all-wire hutches: 1” × 2” welded galvanized wire, ½” × 1” wire, and J-clips.

The wire-cutting pliers need to be large enough to give substantial leverage for cutting through 14-gauge wire. A good cutting tool, made of high-quality steel, isn’t cheap. If you plan to make more than a few hutches, spend enough to get a good pair. Ideally, the jaws will be fairly narrow so they can get a good bite on the ½” × 1” wire. Some rabbit raisers buy a second, smaller pair for working with the smaller mesh wire if they can’t find a larger pair with narrow jaws. Unbeveled cutting jaws will make a flush cut; the result will be a smoother hutch with few sharp edges. Less leverage is required with the smaller mesh wire. Plastic handle grips will make your pliers more comfortable, and wearing a leather glove will help prevent blisters.

J-clip pliers are made for use with J-clips. When squeezed tightly around two parallel wires, they produce a clamp unsurpassed for hutch making. It is true that you can use hog rings or C-rings and hog ring pliers; you can even get away with twisting wire stubs or other short pieces of wire around cage sections. These items and techniques will work, but they are time-consuming and usually will not produce as attractive and durable a hutch.

A metal bending brake is probably more efficient than a hammer and 2 × 4 for bending wire, but it is hardly worth the investment unless you build an extremely large rabbitry. If you have access to one, you will save a little time. Power wire-cutting shears are also on the market, but their cost is justified only if you plan to build a great many hutches.

To fasten the pieces together, use J-clips and special pliers. Space clips every 2 or 3 inches apart.

When buildingyour wire cage, form corners by bending the wire pieces around a straight-edged wooden board.

You will need welded wire fencing in both 14-gauge 1” × 2” and ½” × 1”, or 16-gauge ½” × 1”. The 14-gauge wire is heavier, better, and more expensive, but is more difficult to obtain in many areas. Instead of 1” × 2” wire you may substitute 1” × 1” or 1” × ½”. Both of these will make a sturdier cage, but the cage will be overbuilt and not worth the extra expense and extra work (more cutting), unless you plan to raise the giant, extra-heavy breeds of rabbits, or you already have some of this wire available, or are offered some at a bargain price.

Welded wire comes in basically two types – galvanized before welding and galvanized after welding. Buy the latter. It costs more, but is more rigid and will last longer. Welded wire wears out by oxidation, and wire that is galvanized after welding has more material to oxidize. It will appear thicker, especially at the joints, than wire galvanized before welding, which is smoother to the touch. You can build with wire galvanized before welding but the results will not be as satisfactory.

Sometimes it is possible to find “aluminized” welded wire instead of galvanized. This is very good wire. If you can find some, it makes an excellent hutch.

Some rabbit breeders have experimented with vinyl-covered welded wire. Rabbits love to gnaw, however, and easily can strip the vinyl covering from the wire, which is ungalvanized and soon will rust.

Another point: there is both 1” × 2” wire and 2” × 1” wire. The former has wires every inch of the width of the roll. The latter has wires every 2 inches of the width of the roll. The 1” × 2” is better, but 2” × 1” will work. When calculating dimensions keep in mind that you lose an inch or two each time you cut this wire.

As you can see from the picture, the recommended door latches are easy to fabricate from heavy galvanized metal that can be riveted or bolted together. These latches are so inexpensive, however, that buying them seems a better use of time, unless you happen to be adept at metal working and already have a supply of bolts or rivets and a riveter. The same can be said for the door hangers.

Two types of galvanized metal door latches. Tabs at the top bend around door wire; clasp pivots to swing upward to left or right.

All-wire rabbit hutches consist of little more than boxes with 1” × 2” wire on front, back, top, and sides, and ½” × 1” wire on the bottom. How big to make the boxes and how many to make is up to you. Here are a few points for consideration.

Single vs. Multiple Hutches. Making single hutches at a time will give you total flexibility in hutch layout or rabbitry configuration. Rabbits tend to multiply, so your rabbitry is likely to grow and to change shape or design. Single hutches give you the flexibility you might want to get in and out of rabbit raising, to move, or to build totally new facilities. You can move single hutches easily. They appeal more to others who may purchase them from you later and use them in a different arrangement.

Multiple hutch units will save you time overall because you divide them with shared partitions and assemble them faster, with less cutting and fastening. They won’t necessarily save you money on materials, however, because single shared partitions demand more costly ½” × 1” wire instead of 1” × 2”. This additional expense can be debated, however, if you have purchased the ½” × 1” in 50’or 100’ rolls, and have extra left over anyway. A good compromise is building hutches in 2-unit or 3-unit modules for openers, unless you are determined to start big and have firm plans for a great many hutches. You can also use leftover floor wire for nest boxes, as described later.

Double-unit all-wire hutches. These hutches can be hung double-decker style, as shown.

Size Considerations. While overall dimensions of hutches are up to you, as they can be made in just about any size up to maximum widths of available wire, there are three other considerations regarding size.

• How much room the rabbit needs. Provide nearly a square foot of floor space per pound of adult doe. A 2 ½’ × 3’ hutch will accommodate a medium-size (meat breed) doe and her litter to weaning time. It will, of course, be sufficient for smaller breeds as well. Hutches for bucks and young growing stock can be half that size or a 2-compartment, 2-door hutch of the same size.

• How big a hutch is convenient for the rabbit keeper. For example, maximum depth front to back should not exceed 2 ½’. If the hutch is deeper you won’t be able to catch rabbits in the back unless you have the reach of a professional basketball player.

• Their location. If you are going to build hutches to fit inside a specific existing building, such as a garage or shed, you may have to adjust the hutch size accordingly (within the above guidelines).

For ease and speed of construction, the ideal situation is to purchase 3 sizes of welded wire. These include a roll of floor wire (½” × 1”) of the desired width, a roll of top wire (1” × 2”) of the same width as the floor wire, and a roll (or rolls) of side (and front and rear) wire of the desired height (usually 16” or 18” for the medium breeds, but 24” for the giants and as little as 12” or 15” for the dwarf and small breeds). One can even make a case for buying a fourth size of wire for doors. Available widths for welded wire are 12”, 15”, 18”, 24”, 30”, 36”, 48”, 60”, and 72”.

I’m going to describe 2 building schemes – the first if you wish to purchase materials for up to 10 hutches for breeding does of the medium breeds, and the second if you plan to build more than that of the same size. You will be able to decide from these two approaches which will be better for you. Because rolls of less than 100’ will cost you more per foot, the first approach will save you money if you plan to build only 10 hutches.

Purchase 100’ of 1” × 2” wire, 36” wide. Purchase either 26’ of ½” × 1” wire that is 36” wide or 31’ of ½” × 1” wire that is 30” wide. If you plan to build all-wire nest boxes, as described later, you will need more of the ½” × 1” wire, so plan and buy accordingly. Buy 2 pounds of J-clips. There are about 450 to the pound. Each hutch takes about 90 clips, and you will bend a few out of shape as you get used to working with them.

Here’s how to build these hutches one at a time.

Step 1. Cut the Front, Back, and Top. From the roll of 1” × 2” wire, cut a piece 62” long. Cut it flush and, while you’re at it, cut the stubs off flush from the rest of the roll. Lay the piece on the floor so it curls down (humps up). Place your feet on one end and gently bend the other toward you, moving your feet forward as necessary to flatten the wire. Take care not to kink it; simply reverse the curve with enough pressure to take the bend out of the roll. Now turn it over before forming 90° corners. This is important so you don’t bend against the welded joints, but with them. Most rolls of wire come with the 1” wires on top of the 2” wires as you view the roll before unrolling. If your wire is rolled the opposite way, then note it, and do not bend against the welds.

With the wire on the floor, measure 16” and lay your 2 × 4 board across it at that point. Stand on the 2 × 4 and pull the 16” section toward you gently. Hold the 16” end, reach down with your hammer, and gently strike each strand of wire against the 2 × 4 to make a 90° angle. Now turn around, measure 16” from the other end and repeat the bending process. You have just formed the front, the back, and the top. Set it aside.

Cutting plan for the individual all-wire hutch, 30” × 36” × 16”. This hutch will house a medium-size meat-breed doe and her litter.

Step 2. Cut the Sides. next, cut 30” more off the roll and flatten the resulting 30” × 36” piece as above. Cut it flush and cut the stubs flush off the roll. (As you cut, notice that a slight flick of the wrist down and away from the welds will snap the wire off cleanly with little effort.) Measure 16” up (you are splitting the piece) and cut off flush. The remaining piece will be 30” × 18” (plus stubs). Measure 16” down and cut off 2” (plus stubs). The 2” “waste” strip will be from the center. You will use it later, so set it aside. You now have the sides (ends) of your hutch.

Step 3. Cut the floor. If you bought 36” wide, ½” × 1” wire, cut off 30” flush and cut the stubs off the roll. If you bought 30” wire, cut off 36”. Do not flatten this piece of floor wire, which curves or humps with the ½” wires up, unless it has an extreme curl (perhaps if it is cut from the inside of the roll, where it is curled tighter, in a smaller diameter). The idea is to have the floor of the hutch with the ½” wires up to provide a smoother surface for the rabbits, and to keep an upward spring that will eliminate sagging from the weight of the rabbits.

Now you are ready to assemble the hutch. You have cut out all the pieces except for the door and some more 2” strips that you will clip later to the 4 sides near the floor as a “baby saver” feature. More about that later.

Step 4. Fasten the Sides in Place. Place a J-clip in the jaws of the J-clip pliers and fasten the side sections (the 16” × 30” sections) to the front, top, and back sections. After a little practice you will find that squeezing the J-clips on requires a little flip of the wrist or a second squeeze to assure that the clip is tight. Use a J-clip every 4”, starting with the corners. Make sure the vertical 1” wires are on the outside of the hutch. That way you will have horizontal wires on the inside where they will make neat, tight corners when fastened to the front-top-back section.

Step 5. Fasten the Floor. After fastening the ends to the front, back, and top, turn the hutch on its top and lay the floor wire on it with the curve and the ½” wires down (toward the top of the hutch). Remember that the ½” wires provide the smoother floor and that an upward spring will prevent floor sag.

Clip the floor wire on, starting in one corner, again using clips every 4”. If the fit is too tight in a corner (this can happen if the 1” × 2” wire is made by a different manufacturer than the one who made the ½” × 1” wire), notch out the ½” corners of the floor wire.

From what looked like a flimsy beginning, you will find that you now have quite a sturdy hutch. Clipped together, the resulting wire box is extremely rigid.

Now you are ready to cut out the door opening and attach the door.

Step 6. Cutting a Door Opening. Door size and position are very important, so stop and ponder the situation. The door should be located to one side of the front (a 3’ side) because you want to leave space on the front for attachment of a feeder and space to fill a waterer, be it a crock, bottle with tube or valve, or automatic watering fount or valve. The door opening must also be large enough to admit a nest box, which you will be putting in and taking out regularly.

If you use an all-wire nest box (which I recommend and explain how to build), a door opening that is 12” wide and 11” high is large enough yet not too large. Remember that, while the door must be conveniently large, you are cutting into the front of the hutch and weakening it somewhat, so a door that is unnecessarily large doesn’t do the hutch a lot of good. In any event, be sure to consider the dimensions of the nest box and door together.

For this hutch, I recommend a door opening of 12” × 11” with a door that is 14” × 12” and swings up and in.

Stand the hutch on its back, with the front up and the floor closest to you as you approach it with your wire cutters. Measure 4” over from the left and 4” up from the bottom. Cut the bottom strands to the right to make a 12” opening. Cut up 11” on each side and 12” across the top. Very important: Do not cut these strands flush but leave stubs about ½” long all the way around the opening. Once you have the opening cut out, use your slip-joint pliers to bend these stubs inward or outward around the outermost wire to form an opening with no sharp projections. This is important because if you cut the stubs off, even with flush-cutting wire cutters, the opening would be sharp. The result would be scratched hands, arms, and rabbits. There are other ways to do it: You could cut them off flush and file them smooth or cover them with flanges of sheet metal. I find leaving stubs and bending them over to be less time-consuming and more satisfactory.

Door overlaps opening by 1” on sides and bottom and swings inward.

Step 7. Attaching the Door. For the door, cut 12” of 1” × 2” wire from the 36”-wide roll. Measure down 14” and cut with all the cuts flush. While you are at it, measure down another 14”, cut another door for the next hutch, and set it aside. You will have a piece 6” × 12”. Cut the stubs off that and off the end of the roll. Set the small piece aside.

Before you attach the door, attach the latch. Position it up 2” from the bottom of the center of the door. It fits over the strands 2” apart. If you lay it on a bench or the floor you can flatten it easily over the wire with your hammer. If you wait until it’s on the door to do this, you will have a difficult time. With the latch on, fit the door inside the door opening and clip it with J-clips to the top of the opening.

Use a J-clip on each end and 3 across the middle. Do not give them such a tight squeeze and the door will swing freely. Your door will overlap the sides and bottom by an inch, and the latch should work easily. Give it a drop of oil if it doesn’t.

Now swing the door to the top of the cage (the ceiling) and, 5” over from the left edge of the top, squeeze the door hanger onto the top of the cage with your slip-joint pliers. When the cage is upright, the hanger will hold the door up while you reach into the cage. Give the door a push and it will swing loose and shut. The beauty of this door is that it is always inside the cage, not out in the aisle to snag your sleeve. Even if you forget to latch it, your rabbits cannot escape; it will stay shut no matter how hard they push it.

Step 8. Add a “Baby Saver.” The hutch now looks finished, and in fact it is usable, but it needs some finishing touches. To prevent baby rabbits from falling out of the hutch if they fall out of the nest box, a “baby saver” is needed.

Take the 2”-wide strip you set aside when you split the 36” wire for front and back sections. “Stagger” it over one end at the bottom and fasten it with J-clips every 6”. This will close the openings at the bottom to ½” × 1”, up 2 ½” and will prevent the babies from falling through. Cut a 2” strip for the front and another for the back and fasten them on. When you split another front and back section for the next hutch, clip that one on the other end. When you get to the end of the roll, you will find that you will be able to build 10 hutches in this manner and have enough material for the baby saver feature. In the meantime, save the pieces from the door openings and doors for later use as hay racks. We’ll discuss them later.

If you plan to build more hutches – even if you don’t plan to build them all now – the following is a better plan. It will build up to 36 hutches.

Addingthe “baby saver” feature –½” × 1” wire fastened around the bottom of the sides of the hutch.

Buy a roll of 1” × 2” “side” wire, 100’ long, either 18” or 15” wide (depending upon whether you raise medium or small rabbits), for every 9 hutches you plan to build (4 rolls for 36 hutches). Also buy a 100’ roll of 30” -wide 1” × 2” “top” wire, a 100’ roll of 36”-wide ½” × 1” floor wire, and a 50’ roll of 12”-wide 1” × 2” “door” wire.

Building Plan. Measure and cut off 11’ of the side wire. Form three 90° corners at 30” and 36” intervals around your 2 × 4 and fasten the remaining corner with J-clips. Cut off 3’ of the 30” top wire and fasten it on. Cut off 42” of the 36” floor wire. With your 2 × 4 and hammer, bend up 3” at 90° on all 4 sides, cutting out the corners, to form a box. You have now built the baby saver feature right into the floor. Because it is all one piece, the hutch will be considerably stronger this way. Fasten the floor as described earlier, but also fasten the baby saver sides to the front, back, and ends of the hutch. Make the doors as described earlier.

Cutting plan for an all-wire hutch when you build 10 or more.

If you decide to build multiple-hutch units with shared partitions, use the ½” × 1” wire to divide them. Otherwise, the rabbits may fight through the partitions. Order your wire supply accordingly.

To equip this hutch completely, you will want to attach a self-feeding hopper. Farm stores and rabbitry supply houses have them in various sizes. The trough should be positioned about 4” above the floor for small and medium breeds. The hopper portion remains outside the hutch for easy filling by the rabbit keeper. The trough is inside. It takes up no floor space, and it is high enough and narrow enough to keep the rabbits from fouling it.

Successful rabbit raisers have abandoned crockery feeders (which cost as much or more anyway, and often break) for these self-feeders, which attach with 2 spring wire hooks on each side and, of course, detach easily for periodic cleaning. Tin cans have also gone the way of the crock – they are out. Self-feeders have a lip that prevents the rabbits from scratching pellets out, leaving them hungry and the keeper poor from buying more feed to be wasted. Hopper self-feeders are worth the money and in the long run would save you cash over tin cans even if they were made of sterling silver.

A typical self-feeder — hopper variety. This feeder clips to the outside of the hutch and can be filled from outside.

You can make 2 kinds of hay racks easily with the small scraps of 1 × 2 wire that remain from door openings. Both are simple to make, so you have no need to purchase manufactured hay racks.

For the first type, simply take a 6-8” square scrap and bend 2” of it to an acute angle of about 30°. With a couple of J-clips, fasten the 2” side to the front of the hutch wherever it is convenient, even on the door. Fill the rack with a handful of hay and the rabbits will pull it through.

Another type of hay rack is especially useful for feeding alfalfa hay, which has leaves that tend to fall from the stems when pulled by the rabbits. Build it about 6-8” over the trough of the feeder on the inside of the hutch. You simply form a box of 1” × 2” wire and J-clips that projects 2” into the hutch up to the roof and as wide as the feeder trough. Cut a slot in the front of the cage the width of the rack minus a couple of inches, and about 3” high. Any hay leaves that the rabbits don’t eat on the first attempt will fall into the feed trough for a second chance.

Two types of hay racks: simple all-purpose rack, and alfalfa hay rack.

Rabbits require a constant supply of fresh water to grow and maintain health. Rabbit raisers say water is the best food, because without it a rabbit will not eat properly.

Supplying that water can be the most laborious task in rabbit raising – or you can make it so simple that it practically takes care of itself. Let’s review the ways you can supply water to rabbits.

A Tin Can or Other Open Dish. Very poor, as the rabbit will tip it over and go thirsty until you refill it. Difficult to clean, it invites disease. And there is a lot of work involved in refilling if you have many rabbits.

A Crock. Better, because it can’t be tipped. If you use crocks, get the kind with a smaller inside diameter at the bottom than at the top. During freezing weather, the water will expand into ice and slide up. Otherwise it will expand out and break the crock. The problem with crocks is that they are, like the tin can, open and susceptible to fouling by the rabbits. They are also labor-intensive, with lots of refilling and washing.

A Tube Bottle Waterer. The plastic bottle with the drinker tube is a big improvement over the can or crock. The enclosed water supply stays clean. No space is taken from the cage floor. They require less washing than crocks. They will not work in freezing weather, but ice doesn’t break them.

A Plastic Bottle With Drinker Valve. You make this one yourself because, amazingly, nobody manufacturers one. All it takes is a large heavy plastic bottle, such as one for bleach or soda pop, and a drinker valve designed for automatic watering systems. The bottles are free (unless they are returnable for a deposit); the valves cost a dollar or so and are available at farm supply or rabbitry supply houses.

Manual rabbit-watering devices.

With a knife or drill bit, make a hole in the bottle near the bottom, as shown in the drawing. Coat the threads of the valve with epoxy cement and screw or push it in. Use wire as shown to hold the bottle onto the cage. A quart or half gallon bottle works well and supplies plenty of water, although you can use more than one per hutch if necessary. The plastic bottle has all the advantages and disadvantages of the tube bottle except that it is cheaper and more durable, can supply more water, and, if large enough, can cut filling time considerably.

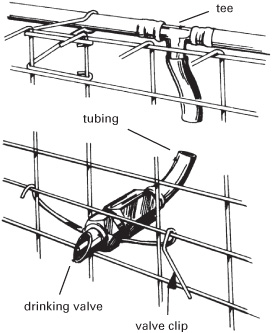

A Semiautomatic Watering System. This is a fine way to water a small rabbitry. You need a tank, which need be no more than a 5-gallon jerry can or pail, leading via flexible or rigid plastic pipe to drinker valves at each hutch. You can buy almost everything locally, with the possible exception of the valves, which were developed for use by poultry.

Semiautomatic watering system with detail of drinking valve.

A very simple setup utilizes flexible black plastic pipe that can be fitted out with various adapters, couplings, elbows, and tees. The pipe runs along the outside of the cage, where it cannot be gnawed, about a foot or so above the hutch floor. Using a simple handtapping tool, you make the holes for the valves, which screw in and protrude into the wire case. The rabbits quickly learn to drink from these valves: their licking dislodges a brass tip, letting the water spill into the rabbits’ mouths. Another type of valve has a spring-activated stem that opens when bitten and closes when released. The latter are better because they rarely leak.

At least one manufacturer, Borak Manufacturing Ltd., produces semiautomatic watering systems as kits, but you can put your own together from various components in farm supply, hardware, or plumbing supply stores.

The beauty of the semiautomatic watering system is that you merely fill the holding tank (ideally with a garden hose) and the rabbits drink a constant supply of fresh water that remains clean and takes up no floor space in the hutch. In addition, you can keep this water flowing in the coldest weather by inserting electric heating cables inside the pipes. You can buy these cables in various lengths, depending on how many cages you have, and they can be operated manually or with a simple air-temperature-activated thermostat. Most of them deliver 2 ½ watts per foot but some produce more heat. Because they are inside the pipe, they need to produce very little heat to keep the water flowing. In severe climates you should use two such cables inside the pipe, activating one with a thermostat and the other manually when the temperature really drops. Without heating cables, you can keep the pipes from freezing by draining them at night. The Borak system is engineered so that you can conveniently disconnect the whole system, if you have a small rabbitry, and take it indoors during freezing nights. All rabbit raisers should consider the semiautomatic system.

An Automatic Watering System. This ultimate system is simply the semiautomatic system with a piped water supply from a well or city water system. It requires the equipment of a semiautomatic system as well as a means of reducing the pressure before water enters the plastic supply pipe to the valves. One way to reduce pressure is a float valve in the tank (like a toilet tank). As the rabbits drink, the float valve allows more water to enter the tank, keeping it constantly full. Pressure-reducing valves are also available. You can keep your float valve and tank system functioning in cold weather by coiling a length of heating cable inside the tank.

Automatic watering system with detail of pressure-reducing and filtering equipment.

Rabbitry supply houses will provide all the materials you require for your watering system if you send them a simple dimensional diagram of your hutch layout.

While some rabbit raisers may be put off by the plumbing and electrical aspects of such a system, you can put one together quite easily. Once installed it takes all the hard work – the hauling and pouring of water – out of caring for rabbits.

To sum up the watering situation, while it is common to begin with crocks or bottles, a piped system can actually cost you less per hutch if you have a large number of hutches and under any circumstances costs very little more. It is important, however, to have all your hutches in place before installing the system, particularly if you will need heating cables, which cannot be shortened or lengthened.

Place a nest box in an all-wire hutch on the 27th day after you mate the doe. The littler will be born in it on the 31st day, ordinarily. You must use one because of the open nature of the all-wire hutch. There are basically 3 kinds of nest boxes to choose from.

You can make your own nest box from wood. Be sure to cover all the edges with metal; if you do not, they will be gnawed to nothing. For the medium breeds, make the dimensions 10” × 11” of floor space and 8” high. Cut the front down to about 4” for easy use by very young rabbits. Be sure to drill 6 or 7 drainage holes in the floor. Don’t put a cover on it as it will become damp. After each use a wooden nest box must be washed, disinfected, and left to dry in the sun.

You can buy ready-made galvanized metal nest boxes. They have removable hardboard floors, but because the tops are partially enclosed, these boxes often become damp. Dampness endangers rabbit health. It’s also difficult to see into these boxes for daily inspection of the litter.

You can buy or build all-wire nest boxes with removable corrugated cardboard liners. This is the type of nest box I have used exclusively for many years and strongly recommend. The box is made with ½” × 1” floor wire and J-clips, and it has metal flanges covering the top edges to protect the rabbits from injury as they hop in and out.

In very cold weather, use it with the corrugated cardboard liner, perhaps with an extra layer of corrugated cardboard or foam plastic to insulate the floor. Use a new liner, free of any possible germs, for each litter and destroy the liner later. You can cut these corrugated liners from boxes, usually obtainable free.

In warm weather, cut cardboard for only the floor and use a shallower bedding of shavings and straw. Leaving the wire mesh sides open gives plenty of ventilation, which is very important to guard against dampness and extreme heat, two rabbit killers. The open mesh provides you a fine view of the litter’s daily progress.