This material was taken from Making Homemade Cheeses & Butter by Phyllis Hobson, Garden Way Publishing.

If you have a couple of goats or a cow on your homestead (and if you do not you are missing one of the most satisfying aspects of country life), you are sure to find yourself with several gallons of surplus milk on hand. Few families, even those with several milk drinkers, can keep up with the output of a good cow on green pasture, and most goats will average a gallon of milk a day during the summer months.

You can make butter and buttermilk, of course, or you can make yogurt; you can freeze packages of butter or cartons of whole milk for the less bountiful winter months; you may even want to can the milk.

But the best solution to a surplus of milk is cheese — the most delicious, nutritious method of preserving milk yet devised.

Even if you do not have a cow or goats of your own, chances are good that you can find a source of fresh milk from a farmer or at a dairy where you can buy raw milk that is free from chemicals. During the summer months, when the animals are eating lush pasture and the milk is plentiful, you often can buy milk at a lower price.

The instructions for making cheese sound complicated, but the process is really much simpler than baking a cake. For each recipe read the Basic Directions through first, then read the specific recipe. Read each step carefully as you go. With only a little practice you can become an expert at making cheese.

As you gain confidence, you will learn the variables of cheese making — the degree of ripening of the milk and its effect on the flavor, the length of time the curd is heated and how that affects the texture, the amount of salt, the number of bricks used in pressing and the effect on moisture content, and how long the cheese is cured for sharpness of taste. All of these variables affect the finished product and produce the many varieties of flavor and texture. The more you learn about it, the more fascinating cheese making will become.

There are basically three kinds of cheese: hard, soft, and cottage. Hard cheese is the curd of milk (the white, solid portion) separated from the whey (the watery, clear liquid). Once separated, the curd is pressed into a solid cake and aged for flavor. Well-pressed, well-aged cheese, will keep for months. Most hard cheeses can be eaten immediately but are better flavored if they are aged. The longer the aging period, the sharper the flavor. The heavier the pressing weight, the harder the texture. Hard cheese is best when made of whole milk.

Soft cheese is made the same way as hard cheese, but it is pressed just briefly. It is not paraffined and is aged a short time or not at all. Most soft cheeses can be eaten immediately and are best eaten within a few weeks. Cheeses such as Camembert, Gorgonzola, and Roquefort are soft cheese which have been put aside to cure. They do not keep as long as hard cheese because of their higher moisture content. Soft cheese may be made of whole or skim milk.

Cottage cheese is a soft cheese prepared from a high-moisture curd that is not allowed to cure. Commercially it usually is made of skim milk, but it can be made of whole milk. Cottage cheese is the simplest of all cheese to make.

The list of equipment needed to make cheese is long; but do not let that scare you off. Improvise with your equipment. Most of the necessary utensils are already in your kitchen. A strainer can be made by punching holes in a restaurant-size can, but a colander or large sieve works best. A floating dairy thermometer works fine for cheese making, but almost any thermometer that can be immersed will do. A coffee can, a few boards, and a broomstick can be transformed into a cheese press.

Equipment

cheese form

follower

cheese press

2 large pots

strainer

thermometer

long-handled spoon

large knife

2 pieces of cheescloth, 1 square yard each

6 to 8 bricks

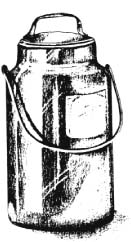

1 pound paraffin

You can make your own cheese form from a 2-pound coffee can by punching nail holes in the bottom of the can. Be sure to punch the holes from the inside out so the rough edges are on the outside of the can and will not tear the cheese. The cheese form is lined with cheesecloth and filled with the wet curd, which then is covered with another piece of cheesecloth before the follower is inserted for pressing. The excess whey drains from the curd through the nail holes in the can. You can also buy cheese forms.

A follower is a circle of ½-inch plywood or a 1-inch board cut just enough smaller in diameter than the coffee can so that it can be inserted inside the can and moved up and down easily. The follower forces the wet curd down, forming a solid cake in the bottom of the can and squeezing out the whey.

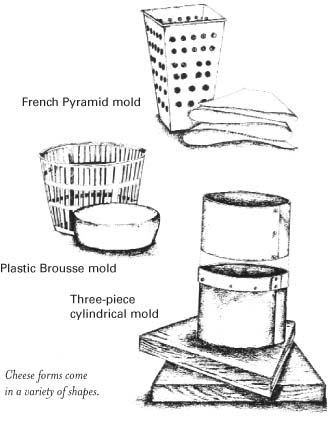

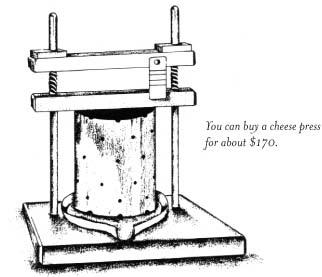

Cheese presses can be bought, substituted for by an old-fashioned lard press, or you can make your own in an afternoon with some scrap wood and a broomstick. (See illustration.)

To make your own cheese press, take a piece of I-inch plywood or a 1-inch by 12-inch board and cut the wood to make 2 pieces about 11 ½ inches by 18 inches each. Drill a hole about 1 inch in diameter in the center of one of the boards; whey will drain through this hole. In the other board, drill 2 holes, 1 inch in diameter each, 2 inches from each end. These holes should be just big enough so that the broomstick can move through them easily.

A cheese press can be made from scrap wood, a broomstick, bricks, and a 2-pound coffee can.

You can buy a cheese press for about $170.

Cut the broomstick into 3 lengths: 2 pieces 18 inches long and 1 piece 15 inches long. Nail each 18-inch length of broomstick 2 inches from the ends of the bottom board, matching the holes in the top board. Nail the other length to the center of the top board, and nail the round follower to the broomstick at the other end. Nail 2 blocks of wood to the bottom or set the press on 2 bricks or blocks so that you can slide a container under the drainage hole to catch the whey (an ice cube tray works great).

The curd is poured into the cheesecloth-lined cheese form (coffee can) which is set on the press. The ends of the cheesecloth are folded over the curd. The follower is set in place, and the top board is weighed down with 1 or 2 bricks. The weighted follower exerts slow pressure on the cheese, forcing the whey out. Up to 4 bricks may be added later to make a firmer cheese.

For a container, I set a 24-quart hot-water canner inside a 36-quart canner, double-boiler style. I recommend them because they are lightweight (4 gallons of milk can get heavy), and they are porcelain enamel covered (aluminum is affected by the acid in the curd). The 24-quart canner holds 4 or more gallons of milk, is not too deep to cut the curd with a long-bladed knife (such as a bread knife), and is easily handled. These pots can be sued at canning time to process tomatoes, peaches, and other acid fruits and vegetables.

To make cheese you need raw goats’ or cows’ milk, a starter, rennet, and salt. You can add color if you like your cheese bright orange color, but I prefer cheese in its natural, creamy white color.

Raw whole milk from goats or cows makes the richest cheese, but partially skimmed milk can be used. Preservatives are often added to milk that is labeled “pasteurized,” so only raw milk can be used; otherwise, your milk may not form curds. Neither can you use powdered milk. For one thing, it has been over-processed; for another, skim milk makes a poor quality cheese.

Use fresh, high-quality milk from animals free from disease or udder infections. It is very important not to use milk from any animal that has been treated with an antibiotic for at least 3 days after the last treatment. A very small quantity of antibiotic in the milk will keep the acid from developing during the cheese making process.

The milk may be raw or pasteurized, held in the refrigerator for several days or used fresh from the animal. It must be warmed to room temperature, then held until it has developed some lactic acid (ripened) before you start to make the cheese. It should be only slightly acid tasting; more acid develops as the cheese is made.

It is best to use a mixture of evening and morning milk. Cool the evening milk to a temperature of 60°F and hold it at that temperature overnight. Otherwise it may develop too much acid. Cool the morning milk to 60°F before mixing with the evening milk.

If you use only morning milk, cool it to 60 or 70°F and ripen it 3 or 4 hours. Otherwise it may not develop enough acid to produce the desired flavor and may have a weak body.

If you are milking 1 cow or only a few goats, you will have to save a mixture of morning and evening milk in the refrigerator until you have a surplus of 3 or 4 gallons.

When you are ready to make the cheese, select 10 or 12 quarts of your very best milk. Remember that poor quality milk makes poor quality cheese. Plan that 4 quarts of milk will make about 1 pound of hard cheese, slightly more soft cheese, or about 1 quart of cottage cheese.

Some type of starter is necessary to develop the proper amount of acid for good cheese flavor. Different starters will produce different tastes. You can buy buttermilk, yogurt, or a commercial powdered cheese starter, or you can make a tart homemade starter by holding 2 cups of fresh milk at room temperature for 12 to 24 hours, until it curdles, or clabbers.

Rennet is a commercial product made from the stomach lining of young animals. The enzyme action of rennet causes the milk to coagulate (curdle) in less than an hour, making the curd formation more predictable for cheese making. Rennet is available in extract or tablet form from drug, grocery, or dairy supply stores. You can buy it in health food stores or in the special cheese making sections of gourmet food shops. Or you can order it by mail.

Because natural rennet is of animal origin, many vegetarians prefer not to use it in making cheese. For that reason, a new, all-vegetable rennet is available in health food stores.

After you have made cheese a few times, you will learn the exact amount of salt that suits your taste, but some salt is needed for flavor. Our recipes call for a minimum amount. You can use ordinary table salt, but flake salt is absorbed faster. Morton flake salt is available in some stores.

1. Ripen the Milk. Warm the milk to 86°F and add 2 cups starter; stir thoroughly for 2 minutes to be sure it is well incorporated into the milk. Cover and let it set in a warm place, perhaps overnight. In the morning, taste the milk. If it has a slightly acid taste it is ready for the next step.

2. Add the Rennet. With the milk at room temperature, add ½ teaspoon rennet liquid or 1 rennet tablet dissolved in ½ cup cool water. Stir for 2 minutes to mix the rennet in thoroughly. Cover the container and let it remain undisturbed until the milk has coagulated — about 30 to 45 minutes.

3. Cut the Curd. When the curd is firm and a small amount of whey appears on the surface, the curd is ready to be cut. With a clean knife, slice the curd into half-inch cubes. First slice through every half-inch lengthwise. Then slant the knife as much as possible and cut crosswise in the opposite direction. Rotate the pan a quarter turn and repeat. Stir the curd carefully with a wooden spoon or paddle and cut any cubes that do not conform to size. Stir carefully to prevent breaking the pieces of curd.

To cut the curd, use a clean, long knife and slice the curd at half-inch intervals. Then slant the knife as much as possible and cut through the curd at a slant. Rotate the pan a quarter turn and repeat the pattern at right angles to the first cut.

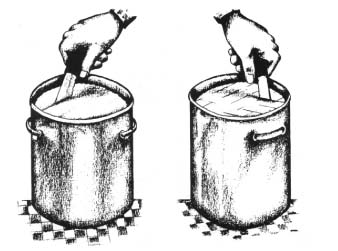

4. Heat the Curd. Place a small container into a larger one filled with warm water, double-boiler style, and heat the curds and whey slowly at the rate of 2 degrees every 5 minutes. Heat to a temperature of 100°F in 30 to 40 minutes, then hold at this temperature until the curd has developed the desired firmness. Keep stirring gently to prevent the cubes of curd from sticking together and forming lumps. As it becomes firmer, the curd will need less stirring to keep it from lumping.

Test the curd for firmness by squeezing a small handful gently, then releasing it quickly. If it breaks apart easily and shows very little tendency to stick together, it is ready. The curd should reach this stage 1 ½ to 2 ½ hours after you added the rennet to the milk.

It is very important that the curd be firm enough when you remove the whey. If it is not, the cheese may have a weak, pasty body and may develop a sour or undesirable flavor. If it is too firm, the cheese will be dry and weak-flavored.

When the curd is firm, remove the container from the warm water.

5. Remove the Whey. Pour the curd and whey into a large container which you have lined with cheesecloth. Then lift the cheesecloth with the curd inside and let it drain in a colander or large strainer. A 1-gallon can with drain holes is convenient for this step.

When most of the whey has drained off, remove the curd from the cheesecloth, put it in a container, and tilt it several times to remove any whey that drains from the curd. Stir occasionally to keep the curd as free from lumps as possible.

Stir the curd or work it with your hands to keep the curds separated. When it has cooled to 90°F, and has a rubbery texture that squeaks when you chew a small piece, it is ready to be salted.

Be sure to save the whey. It is very nutritious and is relished by livestock and household pets. We save the whey for our chickens and pigs, but many people enjoy drinking it or cooking with it.

6. Salt the Curd. Sprinkle 1 to 2 tablespoons of flake salt evenly throughout the curd and mix it in well. As soon as the salt has dissolved and you are sure the curd has cooled to 85°F, spoon the curd into the cheese form which has been lined, sides and bottom, with cheesecloth. Be sure the curd has cooled to 85°F.

7. Press the Curd. After you have filled the cheese form with curd, place a circle of cheesecloth on top. Then insert the wooden follower and put the cheese form in the cheese press.

Start with a weight of 3 or 4 bricks or 10 minutes, remove the follower, and drain off any whey that has collected inside the can. Then replace the follower and add a brick at a time until you have 6 to 8 bricks pressing the cheese. When it has been under this much pressure for an hour, the cheese should be ready to dress.

Pressing is extremely important. If you want a hard, dry cheese, you will need 30 or more pounds of pressure for a 2 ½ to 3 pound cheese.

8. Dress the Cheese. Remove the weights and follower and turn the cheese form upside down so the cheese will drop. You may have to tug at the cheesecloth to get it started. Remove the cheesecloth from the cheese and dip cheese in warm water to remove any fat from the surface. With your fingers, smooth over any small holes or tears to make a smooth surface. Wipe dry.

Now cut a piece of cheesecloth 2 inches wider than the cheese is thick and long enough to wrap around it with a slight overlap. Roll the cheese tightly using 2 round circles of cheesecloth to cover the ends.

Replace the cheese in the cheese form, insert the follower, and press with the 6 to 8 bricks another 18 to 24 hours.

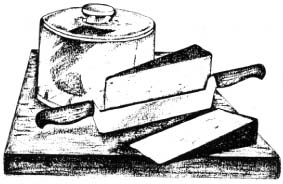

9. Dry the Cheese. At the end of the pressing time, remove the cheese, take off the bandage, wipe the cheese with a clean, dry cloth, and check for any openings or cracks. Wash the cheese in hot water or whey for a firm rind. Seal the holes by dipping the cheese in warm water and smoothing with your fingers or a table knife.

Then put the cheese on a shelf in a cool, dry place. Turn and wipe it daily until the surface feels dry and the rind has started to form. This takes from 3 to 5 days.

10. Paraffin the Cheese. Heat ½ pound of paraffin to 210°F in a pie pan or disposable aluminum pan deep enough to immerse half the cheese at one time. Be sure to heat the paraffin over hot water — never over direct heat.

Hold the cheese in the hot paraffin for about 10 seconds. Remove and let harden a minute or so, then immerse the other half. Check to be sure the surface is covered completely.

11. Cure the Cheese. Now put the cheese back on the shelf to cure. Turn it daily. Wash and sun the shelf once a week. After about 6 weeks of curing at a temperature of 40 to 60°F, the cheese will have a firm body and a mild flavor. Cheese with a sharp flavor requires 3 to 5 months or longer curing. The lower the temperature the longer the time required. It’s a good idea to test your first cheese for flavor from time to time during the curing period. One way is to cut the cheese into 4 equal parts before paraffining and use 1 of the pieces for tasting.

How long to cure depends on individual taste. As a rule Colby is aged 30 to 90 days and Cheddar 6 months or more. Romano is cured at least 5 months. Other cheeses are cured sometimes no more than 2 or 3 weeks. The cooler the temperature in the curing room, the longer it takes to ripen. Once you have the temperature and time to suit your taste, you will know exactly when your cheese will be ready.

Remember, these are general instructions to be used for hard cheese. When you follow the specific recipes, you will find many variations, particularly for processing temperatures and pressing times.

CHEDDAR

There are several ways to make cheddar. To make my version, follow the Basic Directions through Step 5, removing the whey. Then place the dubs of heated curd in a colander and heat to 100°F. This may be done in the oven or in a double-boiler arrangement on top of the stove. It is important to keep the temperature between 95 and 100°F for 1 ½ hours.

After the first 20 to 30 minutes, the curd will form a solid mass. Then it should be sliced into 1-inch strips which must be turned with a wooden spoon every 15 minutes for even drying. Hold these strips at 100°F for 1 hour. Then remove from the heat and continue with the Basic Directions, beginning at Step 6, salting the curd. Cure for 6 months.

COLBY

To make a small colby cheese, add 3 tablespoons of starter to 1 gallon of lukewarm milk. Let it stand overnight to clabber, then proceed with the Basic Directions through Step 4, heating the curd.

When the curd is heated to the point where it no longer shows a tendency to stick together, remove the container from the heat and let it stand 1 hour, stirring every 5 minutes.

Now continue with Step 6, removing the whey. After pressing the curd for 18 hours, the cheese can be dried a day or so and used as a soft cheese spread or ripened for 30 days.

MOZZARELLA

Mozzarella is a delicate, semi-hard Italian cheese which is not cured but is used fresh. It often is used in Italian dishes.

Follow the Basic Directions to Step 3, cutting the curd. Instead of cutting the curd with a knife, break it up with your hands. Heat the curd to as hot as your hands can stand. Then stir and crumble it until the curds are firm enough to squeak.

Proceed with the Basic Directions at Step 5, removing the whey, and continue to Step 8, dressing the cheese. At this point, remove the pressed cheese from the cheese form and discard cheesecloth wrapping. Set the cheese in the whey which has been heated to 180°F. Cover the container and let stand until cool.

When cool, remove the cheese from the whey and let drain for 24 hours. The cheese is now ready to eat or use in recipes.

FETA

Feta is a white, pickled cheese made from goats’ or ewes’ milk. To make this salt-cured cheese, follow the Basic Directions through Step 3, cutting the curd. In the next step the curd is heated to no more than 95°F and drained when less firm than most hard cheeses.

To remove the whey, the curds and whey are poured into a cloth bag which is hung for 48 hours until the cheese is firm. Feta is not pressed in a cheese form. When firm, the curd is sliced and sprinkled with dry salt, which is worked in with the hands. The cheese is then returned to the cloth bag which is twisted and worked to expel most of the whey and firm the cheese. After 24 hours, the cheese is wiped off and placed on a shelf to form a rind. It is ready to eat in 3 to 4 days.

Soft cheeses usually are mild and aged little, if at all. They do not keep as long as hard cheese. Soft cheeses are not paraffined, but are wrapped in wax paper and stored in the refrigerator until used. Except for a few soft cheeses that are aged, they should be eaten within a week or so for best flavor.

The simplest soft cheese is fresh curds, which Grandmother made by setting fresh warm milk in the sun until the curds separated from the whey. The most familiar soft cheese is cream cheese which is made by draining curds for a few minutes in a cloth bag.

If you gather from this that the making of soft cheese is not nearly as complicated as hard cheese, you are right. Here are some of the simplest recipes.

SWEET CHEESE

Bring 1 gallon of whole milk to a boil. Cool to lukewarm and add 1 pint of buttermilk and 3 well-beaten eggs. Stir gently for 1 minute, then let set until a firm clabber forms. Drain in a cloth bag until firm. The cheese will be ready to eat in 12 hours.

CREAM CHEESE

Add 1 cup of starter to 2 cups of warm milk, and let it set 24 hours. Add to 2 quarts of warm milk and let it clabber another 24 hours. Warm over hot water for 30 minutes, then pour into a cloth bag to drain Let it set one hour. Salt to taste and warp in waxed paper. It may be used immediately for sandwiches, on crackers, or in recipes calling for cream cheese. Refrigerate until used.

Another method of making cream cheese is to add 1 tablespoon of salt to 1 quart of thick sour cream. Place in a drain bag and hang in a cool place to drain for 3 days.

CHEESE SPREAD

Let 2 ½ gallons of skimmed milk sour until thick. Heat very slowly until it is hot to the touch; do not allow to boil. Hold the milk at this temperature until the curds and whey separate. Strain through cheesecloth and allow the curds to cool a little, then crumble with your hands. Makes 4 cups crumbled cheese. Let it set at room temperature 2 to 3 days to age.

To the 4 cups crumbled curds, add 2 teaspoons of soda and mix in with your hands Let it set 30 minutes. Add 1 ½ cups of warm milk, 2 teaspoons of salt, and ⅓ cup of butter Set over boiling water and heat to the boiling point, stirring vigorously. Add 1 cup of cream or milk, a little at a time, stirring after each addition. Cook until smooth. Stir occasionally until cold. Makes 1 ½ quarts of cheese spread.

To make a flavored cheese spread, add 3 tablespoons of crumbled bits of crisply fried bacon, or 1 tablespoon of chopped chives, or 4 tablespoons of chopped, drained pineapple.

DUTCH CHEESE

Set a pan of curded milk on the back of a wood-burning stove and heat very slowly until the curd is separated from the whey. Drain off the whey and pour the curd into a drain bag. Hang and let it drain for 24 hours. Chop the ball of curd and pound until smooth with a potato masher or round-end glass. Add cream, butter, salt, and pepper to taste. Make into small balls, or press in a dish and slice to serve.

GERMAN CHEESE

Put 2 gallons of clabbered milk in an iron pot over low heat and bring it to 180°F in 45 minutes. Drain off the whey and put the curds in a colander. When the curds are cool enough to handle, press it with your hands to extract any remaining whey. The warmer you work it the better. Put the drained curd in a dish and add 2 teaspoons of soda and 1 teaspoon of salt, working in well with your hands. Press the curd with your hands to form a loaf. Let it set for 1 hour, when it will have risen and be ready to slice. It will keep several days in a cool place.

If the cheese is dry and crumbly it may have been heated too much or pressed too long. If it is soft and sticky it was not heated enough or not pressed enough.

CHEESE BALLS

To each pint of drained curd, add 2 ounces of melted butter, 1 teaspoon salt, a dash of pepper, and 2 tablespoons thick cream. Work together until smooth and soft. Make into small balls to serve with salad.

Cottage cheese may be eaten as a spoon cheese or strained (or put through a blender) and used as a low calorie dip or in recipes calling for sour cream. It is best eaten as soon as it is chilled, but it will keep up to a week in the refrigerator.

Homemade cottage cheese does not contain preservatives, so it does not keep as long as the commercial variety usually does.

Method 1

Bring 1 gallon of whole or skimmed milk to 75 to 80°F and add 1 cup of starter. Cover and set in a warm place 12 to 24 hours or until a firm clabber forms and a little whey appears on the surface.

When a clabber is formed, cut into half-inch cubes by passing a long knife through it lengthwise and crosswise. Then set the container in a larger pot containing warm water Warm the curd to 110°F, stirring often to keep it from sticking together. Be careful that you do not overheat.

When the curd reaches the proper temperature, taste it from time to time to test for firmness. When it feels firm enough to your liking (some people like their cottage cheese rather soft; others like it quite firm and granular), immediately pour it into a colander lined with cheesecloth, and drain for 2 minutes. Lift the cheesecloth from the colander and hold under tepid water, gradually running it colder, to rinse off the whey. Place the chilled curd in a dish, add salt and cream to taste, and chill thoroughly before serving.

Method 2

Add 1 cup of starter to 1 gallon of freshly drawn milk. Cover and set in a warm place overnight. In the morning, add half a rennet tablet dissolved in ½ cup of water. Stir 1 minute. Cover again and let it stand undisturbed for 45 minutes. Cut the curd into half-inch cubes, set the container in a larger pot of warm water, and warm the curd to 102°F. Proceed as in Method 1, once the curd has reached the desired temperature and firmness.

Add 1 cup of starter to 2 gallons of warm skimmed milk. Stir well and pour into a large roaster pan with a lid. Place in a warm (90°F) oven (heat off) overnight or for about 12 hours. In the morning take out 1 pint of the clabbered milk and refrigerate it to use as a starter for the next batch. Turn on the oven and set at 100°F. Heat the clabber in the oven for 1 hour, then cut into half-inch cubes. Do not stir or move pan unnecessarily. Leave the milk in the oven until the curds and whey are well separated. When the curd rises to the top of the whey, turn the heat off and let it set until cool. Dip off excess whey; then dip out curds and put them into a cheesecloth-lined colander to drain. Pour curds into a dish and add salt and cream to taste.

Method 4

Heat 1 quart of sour milk in the upper part of a double boiler over hot water. Heat until lukewarm, then line a large strainer with cheesecloth dipped in hot water and pour in the milk. Over the milk pour 1 quart warm water. When the water has drained off, pour another quart of warm water over the milk. Repeat. When the water has drained off for the third time, gather the ends of the cheesecloth to form a bag and hang to drain overnight. Add salt to taste.

Method 5

Pour 2 quarts of clabbered milk into a large pan. Into it slowly pour boiling water, continuing until the curds start to form in the milk. Let set until the curds may be skimmed from the top. Mix curds with cream. Salt lightly.

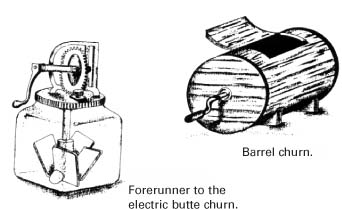

Butter can be made from sweet or sour cream in a variety of equipment ranging from an electric mixer or blender to a plain glass jar with a tight-fitting lid.

If you make butter often, you may want to buy a churn. They vary from the large, old-fashioned, wooden-barrel churns which will accommodate up to 5 gallons of cream to the small, glass-jar, wooden-paddle churns that are still sold by Sears, Roebuck in hand-operated or electric models.

Sweet cream butter takes longer to churn than sour cream butter. If the cream is very fresh it may take several hours to turn to butter. Sour cream churns into butter in 30 to 35 minutes. Both sweet and sour cream churns quicker if they have been aged 2 to 3 days in the refrigerator. Sweet cream butter is sometimes preferred for its mellow, bland flavor. Sour cream butter has a richer taste.

SWEET CREAM BUTTER

If you make butter once a week from the cream accumulated during the week, it will give the cream time to ripen a little, which improves the taste and makes it easier to whip. Or leave the cream a day or so at room temperature until it begins to clabber.

Pour the cold, heavy cream into a chilled mixing bowl. Turn the mixer slowly to high speed and let the cream go through the stages of whipped cream, stiff whipped cream, and finally two separate products — butter and buttermilk. In a churn, turn slowly for 15 to 20 minutes. It is only during the last stage as the butter separates from the buttermilk, that the process needs attention. Then you must turn the speed to low or it will spatter wildly. When the separation has taken place, pour off the buttermilk. (Save the buttermilk. It’s great for making biscuits or pancakes or to drink.)

Now knead the soft butter with a wet wooden spoon or a rubber scraper to force out all the milk, pouring the milk off as you knead. When you have all the milk out, refill the bowl with ice water and continue kneading to wash the remaining milk from the butter. (Any milk left in will cause the butter to spoil.) Pour off the water and repeat until the water is clear.

You now have sweet butter. If you want it salted, add a teaspoon of flake salt. Uncolored butter may be an appetizing cream white color, but if you want it bright yellow, you can add butter color.

One quart of well-separated, heavy cream makes about one pound of butter, and about a half quart of buttermilk.

SOUR CREAM BUTTER

Ripen cream by adding ¼ cup of starter to each quart of heavy cream. Let it set at room temperature for 24 hours, stirring occasionally. Chill the ripened cream 2 to 3 hours before churning.

When it is chilled, pour the cream into a wooden barrel or glass-jar churn. If desired, add butter coloring at this point. Keep the cream and the churn cool and turn the mechanism with a moderately fast, uniform motion. About 30 to 35 minutes of churning usually will bring butter, but the age of the cream, the temperature, and whether the cream is from a morning or a night milking will affect the length of time required.

When the butter is in grains the size of wheat, draw off the buttermilk and add very cold water. Churn slowly for 1 minute, then draw off the water.

Remove the butter to a wooden bowl and sprinkle it with 2 tablespoons of flake salt for each pound of butter. Let stand a few minutes, then work with a wooden paddle to work out any remaining buttermilk or water, and mix in the salt. Taste. If the butter is too salty, wash with cold water. If it needs it, add more salt.

While working, keep the butter cold. If it should become too soft during hot weather, chill the butter until it hardens before finishing.

Making yogurt essentially is the same as making cheese starter. The milk is warmed to 100 to 110°F, the culture is added, and the mixture is kept at the desired temperature for several hours. At about 100°F you can make yogurt in 5 to 6 hours, but you can leave it 10 to 12 hours if like a tarter flavor.

It is important to keep the mixture at the proper temperature for the necessary length of time in order to allow the culture to develop. If you have a yogurt maker, simply follow the manufacturer’s directions. If you don’t use your ingenuity.

Almost fill a thermos (preferably wide mouth) bottle with warm (100°F) milk. Add 2 tablespoons of plain yogurt and mix thoroughly. Put the lid on and warp the thermos in 2 or 3 terry towels. Then set in a warm, draft-free place overnight. (On winter nights, over the furnace register is a good place.)

Pour 1 quart of warm milk in a casserole dish and add 3 tablespoons of plain yogurt. Stir well and cover casserole. Place in warm (100°F) oven with the heat off. Let it set overnight.

Set an electric heating pad at medium temperature and place in the bottom of a cardboard box with a lid. (A large shoe box works well.) Fill small plastic containers with warm milk, add yogurt starter to each, and mix well. Put on lids. Wrap heating pad around containers, then cover with towels to fill box. Put lid on box and let set undisturbed for 5 to 6 hours.

Pour warmed milk into a glass-lidded bowl or casserole. Add yogurt starter and cover with the glass lid or a clear glass pie plate. Place in the sun on a warm (not too hot) summer day and let set 4 to 5 hours. Watch it to make sure it is not shaded as the sun moves.

Grandmother made her clabber by setting a bowl of freshly drawn milk on the back of the stove after supper. She added 1 cup of starter to each 2 quarts of milk and let it set, loosely covered with a dish towel, on the back of the cooling wood range overnight. If you are fortunate enough to have a wood range in your kitchen this method works beautifully.

You can buy cheese making supplies from the following companies. Write for their catalogs.

9015 Maple St.

Milwaukee, WI 53214

P.O. Box 41

Kidron, OH 44636

(330) 857-5757

info@lehmans.com

P.O. Box 85

Ashfield, MA 01330

Simply put, making ice cream and other frozen desserts yourself makes good sense and is a lot of fun. The flavors you can make are literally limitless, and the ingredients are readily available. Your ice cream will cost less than the premium brands and be vastly superior to the cheaper brands. Most importantly, you can control what goes into your ice cream, making it as sinfully rich or as austerely slimming as you want, with no unnecessary ingredients. If you decide to use an ice cream freezer, new ones are available in a wide range of sizes, are relatively inexpensive, and are easier than ever to use.

Homemade ice cream need no longer be a “once-inthe-summer” treat. Why not enjoy it year round?

The basic ingredients of ice cream include a dairy product such as cream or milk, a sweetener, and a flavoring. By making your own ice cream you can interchange ingredients to suit your tastes and resources.

Having your own cow or goat means an abundant supply of fresh milk and is ideal in terms of wholesomeness, availability, and cost. But purchased milk products will also yield a better product than store-bought ice cream, and you’ll still save money. For strict vegetarians, ice cream, sherbet, and frozen yogurt can be made from soy milk.

Whipping Cream. With 36 percent butterfat, this naturally makes the creamiest dessert with that superb cream flavor, but you will pay a price at both the checkout and calorie counters. Most kinds available in grocery stores are ultra-pasteurized and contain emulsifiers and stabilizers.

Light cream. Also called coffee cream, light cream has 20 percent butterfat. It produces a relatively rich ice cream with fewer calories.

Half-and-half. A mixture of milk and cream with 12 percent butterfat, half-and-half makes a satisfactory ice cream with a hint of richness.

Whole Milk. Fresh, whole milk contains 3 ½ percent butterfat. It is the basic ingredient in most ice creams and sherbets.

Low-fat milks. Low-fat (2 percent butterfat), 99 percent fat-free, and skim (less than ½ percent butterfat) milks are useful when you want to limit calories, but you will get a coarser texture in the ice cream.

Nonfat dry milk. An economical choice, nonfat dry milk is handy because it needs no refrigeration prior to reconstituting with water. Mix instant dry milk granules in the proportions recommended on the package. To reconstitute non-instant dry milk powder, combine 1 part powder with 4 parts water, or for a richer ice cream, use 2 parts powder. A blender works well for this, or first mix the powder with a small amount of water to form a paste before adding the remaining water.

Buttermilk. Originally the liquid leftover in the churn after butter was made, today buttermilk is made by adding a bacterial culture to pasteurized skim milk. Its thick, creamy texture, low calories, and tart flavor make it a useful ingredient in many frozen desserts.

Evaporated milk. Evaporated milk is made by removing some of the water from fresh milk, adding various chemical stabilizers; it is then sealed in cans and heat-sterilized. Used undiluted, evaporated milk gives a richer taste and smoother texture to ice cream than plain whole milk.

Yogurt. You can make yogurt with fresh whole, low-fat, skim, or nonfat dry milks and even soy milk. Frozen yogurt made with any of these products will have the characteristic tart, tangy flavor. It is very economical to make your own yogurt. If using purchased yogurt, be sure to buy brands with live bacterial cultures, preferably with no flavoring, or only those with preserves at the bottom and no additives.

Sour cream. Made from light cream and inoculated with a bacterial culture, commercially available sour creams may have texture-enhancing additives. Sour cream helps make ice cream rich and tangy.

Soy milk. As high in protein as cow’s milk, soy milk has only one-third as much fat — and it is unsaturated fat to boot. When making ice cream, add ¼ cup vegetable oil for every 3 cups soy milk to make a richer product. Soy milk powder is available, or soy milk can be made by soaking soybeans overnight, grinding, cooking with water, and straining off the milk.

Much controversy rages over the relative merits of various sweeteners. For simplicity, the recipes here call for the two most readily-used sweeteners, honey and white sugar. Other sweeteners can be easily substituted. A proportion of ¾ cup granulated white sugar or ⅓ cup honey to each 4 cups of dairy product is usual when making ice cream. Syrups and honey tend to give a smoother texture because they control crystal formation.

However, sugar also adds to the overall solids of the mixture in a way that is different from honey and syrups. A high solid content lowers the freezing point for the mixture, causing the ice cream to freeze more solid and be easier to scoop. Honey and syrups often have a higher moisture content than sugar which also affects the product. A little experimenting should give you an idea of the different results to be obtained by using various sweeteners.

Granulated white sugar. Granulated white sugar is the most common sweetener, however, it is totally devoid of nutrients.

Brown sugar. Brown sugar is white sugar with molasses added, which gives it traces of vitamins and minerals. Brown sugar adds a distinctive taste, and should be used in the same proportion as white sugar, though lightly packed.

Honey. Depending on its own taste, honey may add a slight or a strong flavor to your ice cream. Darker honeys are usually stronger and sweeter. Honey that is labeled unfiltered, raw, or uncooked will have traces of vitamins and minerals. Half as much honey is needed to sweeten ice cream as white sugar.

Unsulphured molasses. A by-product of the sugar refining process, molasses contains some iron, calcium, and phosphorus. It has a distinctive flavor that is appropriate only with certain flavors of ice cream. Use ½ cup of molasses for 1 cup of white sugar in recipes.

Maple syrup. This ingredient adds not only sugar, but also its own unique flavor to foods. Be sure to use only pure maple syrup, free of additives, not flavored pancake syrup. Substitute ⅔ cup maple syrup for 1 cup of white sugar.

Light corn syrup. Sometimes used in making fruit ices and sherbets, light corn syrup produces a light, smooth texture with no flavor effect. It is a mixture of refined sugars, partially digested starches, water, salt, and vanilla. A less expensive, homemade sugar syrup or honey may be preferred.

Dark corn syrup. A distinctive flavor, dark corn syrup has the same drawbacks as light corn syrup. Use dark honey or molasses instead.

Fructose. A sugar found naturally in fruit and honey, fructose does not have an adverse affect on a person’s blood sugar level. As it is two-thirds sweeter than white sugar, it can be used in smaller quantities. Substitute ⅓ cup crystalline fructose for 1 cup sugar; liquid fructose varies in concentration, so follow label directions. Although called fruit sugar, the commercially available forms are usually made by extensive refining of corn, sugar beets, or sugar cane.

Maltose. Maltose is most frequently found as barley malt or rice syrup, both the cooked liquid of fermented grain and with a subtle flavor. It does not create blood sugar fluctuations, but maltose is less sweet than other sugars so more must be used. Substitute 1 ½ cups maltose for 1 cup of white sugar.

Sorghum. A molasses-like product, sorghum is made from a plant related to corn. When using sorghum substitute ½ cup sorghum for 1 cup of white sugar.

This is where your creativity really has a chance to flower in ice cream making. Always use pure extracts and the finest ingredients, whether it be vanilla, chocolate, carob, fruits, nuts, coffee, or liqueurs. Using home-grown fruits and nuts is not only a source of pride, but the way to be sure of the best ingredients at a reasonable cost.

These make a smoother frozen product with smaller ice crystals. They also add body and richness, and increase the amount of air that can be incorporated. Since one of the reasons to make your own frozen desserts is to avoid additives, you may choose not to use these. But if you do, it’s best to select ones that add to the nutritional content. Remember, though, these also add extra cost.

Eggs. An excellent inexpensive source of complete protein, eggs also contain certain minerals and vitamins. The egg yolks in custard ice cream help to thicken and add richness. Beaten egg whites also add body and richness as well as making a smoother, fluffier product. Ice creams with eggs also store longer in the freezer.

Cream of tartar. A natural fruit acid made from grapes, cream of tartar can be used to increase volume, to stabilize, and to firm egg whites. Add at the beginning of beating, using ¼ teaspoon to 2–4 whites.

Arrowroot. The powdered starch of several tropical plant roots, arrowroot is an excellent thickener, or filler. Easy to digest, it is clear when diluted and has no chalky taste like cornstarch. As arrowroot is more acid-stable than flour, it works well with fruit. It is effective at lower temperatures and when cooked for a shorter period of time than other thickeners. Use 1 ½ teaspoons arrowroot in place of 1 tablespoon flour or cornstarch.

Cornstarch. A finely milled corn with the germ removed, cornstarch may be used as a thickening agent in cooked custard mixtures to make a smoother ice cream. It has little food value. Use 1 tablespoon in 2 cups cooked liquid when making custard ice cream.

Whole wheat flour. Whole wheat flour can be used as a thickening agent in cooked custard mixtures to make a smoother ice cream. It will contribute a slight amount of food value. Use 1 tablespoon in 2 cups cooked liquid when making custard ice cream.

Unflavored gelatin. Unflavored gelatin is a protein extracted from animal parts, then dried and powdered. It helps to make a smoother ice cream. Dissolve it in water and cook before adding to other ingredients. Use 1 ½ teaspoons in a 1 ½ quart batch of ice cream.

Agar. A sea vegetable high in minerals, agar can be used in place of unflavored gelatin. Agar is available as a concentrated powder, flakes or sticks, and unlike gelatin, it gels without requiring chilling. It is flavorless and highly absorptive. Use 1 ½ tablespoons to 1 quart of liquid.

Salt is frequently used in foods as it heightens and enhances flavors. While an essential element in the body’s health, too much salt can cause problems. It can be omitted from ice cream with little notice.

Ice cream freezers for home use come in sizes ranging from 1 quart to 2 gallons. Some are elaborate and expensive, but most are relatively inexpensive and still very functional. In deciding which ice cream freezer to buy, consider such factors as cost, when and how you want to use it, durability, portability, and storage space needed. A large freezer can be used to make small amounts as well as party-size quantities.

Old-fashioned ice cream churns. These churns are available as either hand-cranked models or as electricity powered units. A large plastic, fiberglass, or wood tub holds a smaller, metal can. The ice cream mixture is placed inside the can along with a dasher or paddle and the assembly is covered. To freeze the ice cream, a brine solution of ice and salt is placed in the tub around the metal can. Turning the crank-and-gear assembly on top of the can rotates the dasher or paddle and mixes the ice cream. The dasher extends the height of the can and scrapes the ice crystals at the edge of the can to the inside. Churning is usually finished in 20 minutes.

Old-fashioned hand-crank model

In-freezer ice cream churn. Such churns include a 1-quart unit with a dasher, metal can, plastic tub, and electrical assembly that uses the frigid air of a deep freezer or refrigerator freezer rather than ice and salt to freeze the mixture inside. Churning is usually completed in 1 ½ hours.

Self-contained ice cream churns. These models come in sizes slightly more and slightly less than 1 quart. Using their own freon freezing unit and powdered electrically, they can make ice cream in 20 minutes. Although expensive, their ease of operation, speed, and lack of mess make them appealing.

With any of these machines, be sure to follow manufacturer’s directions and care instructions. With all machines, it is important to wash, rinse, and thoroughly dry after each use. Wipe around electric motors and gear housings with a dampened, well-squeezed sponge followed by a dry towel.

Ice. Ice is cheapest when made at home. Plan ahead and make plenty, figuring on 8 ice cube trays or 6 pounds of ice to make 1 ½ quarts of ice cream. Ice can be crushed to provide the most surface area for heat exchange, but cubes work reasonably well. Ice can be crushed by putting in a burlap or other heavy sack and hitting with a hammer.

Salt. Salt lowers the freezing temperature of water. Use table salt with ice cubes, and coarser, more slowly dissolving rock salt with crushed ice. For a 1 ½-quart batch of ice cream, you will need 1 ½ cups table salt or 1 cup rock salt. Additional salt will be needed if the ice cream is hardened in the churn.

1. Prepare ice cream or other frozen dessert mixture, pour in bowl, cover, and chill for several hours in the refrigerator. This will give a smoother product with less freezing time.

2. Wash the dasher, lid, and can; rinse and dry. Place in the refrigerator to chill. Keeping the equipment cold will make the process of freezing your mixture go faster.

3. Pour chilled mixture into the can, making sure it is not more than two-thirds full to allow for expansion. Put on the lid.

4. Put the can into the freezer tub and attach the crank-and-gear assembly.

5. Fill the tub one-third full of ice. Sprinkle an even layer of salt on top about ⅛-inch thick. Continue adding ice and salt in the same proportions layer by layer until the tub is filled up to, but not over, the top of the can. The salt-to-ice ratio affects freezing temperature and, therefore, freezing time. Too much salt and the ice cream will freeze too quickly and be coarse; too little salt will keep the mixture from freezing. Many factors influence the ratio, but the best proportion seems to be 8 parts ice to 1 part salt, by weight.

6. If using ice cubes, add 1 cup of cold water to the iceand-salt mixture to help the ice melt and settle. If using crushed ice, let the ice-packed tub set for 5 minutes before beginning to churn. While churning, add more ice and salt, in the same proportions as before, so that it remains up to the top of the can.

7. Start cranking slowly at first — slightly less than 1 revolution per second — until the mixture begins to pull. Then churn as quickly and as steadily as possible for 5 minutes. Finally, churn at a slightly slower rate for a few more minutes, or until the mixture turns reasonably hard.

8. For electrically powdered ice cream churns, fill can with mix and plug in the unit. Allow to churn until it stops in about 15 to 20 minutes. Most kinds have an automatic reset switch that will prevent motor damage by stopping when the ice cream is ready. If the freezer becomes clogged with chunks of ice, the motor may shut off or stall. Restart by turning the can with your hands.

9. When the ice cream is ready, remove the crank-and-gear assembly. Wipe all ice and salt from the top. Remove the lid and lift out the beater. The ice cream should be the texture of mush. Scrape the cream from the beater. Add chopped nuts and fruit or sauce for ripple, if desired. Pack down the cream with a spoon. Cover with several layers of wax paper and replace the lid, putting a cork in the cover hole.

10. Ripen and harden the ice cream by placing in a deep-freezer or refrigerator freezer, or repack in the tub with layers of ice and salt until the can and lid are completely covered. Use more salt than for making the ice cream. Cover the freezer with a blanket or heavy towel and set in a cool place until ready to serve, about an hour.

1. Prepare the ice cream mixture as directed and pour into a shallow tray such as a cake pan or ice-cube tray without the dividers.

2. Place the tray in the freezer compartment of the refrigerator at the coldest setting or a deep freezer for 30 minutes to 1 hour, or until the mixture is mushy but not solid.

3. Scrape the mixture into a chilled bowl and beat it with a rotary beater or electric mixer as rapidly as possible until the mixture is smooth.

4. Return the mixture to the tray and the freezer. When almost frozen solid, repeat the beating process. Add chopped nuts and fruits, liqueur, or ripple sauce, if desired.

5. Return to the tray and cover the cream with plastic wrap to prevent ice crystals from forming on top. Place in the freezer until solid.

Each of these recipes makes 1 ½ quarts or about 6 servings. The recipes can be decreased or increased to accommodate smaller or larger ice cream freezers. If making still-frozen ice cream, these recipes will fill 2 shallow pans.

BASIC VANILLA ICE CREAM

Whether cooked or uncooked, this simple, fast version can be made as rich or as low-calorie as you desire. Variations are infinite.

1 quart heavy or light cream or half-and-half or 2 cups each heavy and light cream

1 cup sugar or ⅓ cup honey

1 tablespoon pure vanilla extract

The above ingredients can be mixed and used as is or the cream can be scalded. Scalding concentrates the milk solids and improves the flavor.

To scald, slowly heat cream in a saucepan until just below the boiling point. Small bubbles will begin to appear around the edges. Stir for several minutes, then remove from heat. Stir in the sweetener. Pour into a bowl, cover, and chill. When completely cooled, add the vanilla. When thoroughly chilled, follow directions for either churned or still-frozen ice cream.

Variations on the Basic Recipe

Super Creamy Vanilla Ice Cream

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe: soften 1 ½ teaspoons unflavored gelatin in ¼ cup water and add with sugar to scalded milk. Continue cooking over low heat until gelatin is dissolved. Or, substitute 1 ½ tablespoons agar.

Ice Milk

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe, substitute whole, low-fat, skim, or reconstituted dry milk for the cream.

Ice Buttermilk

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe, substitute buttermilk for the cream and do not scald.

Ice Sour Cream

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe, substitute sour cream for the cream and do not scald.

Ice Soy Milk

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe, substitute soy milk for the cream, without scalding. Combine soy milk, sweetener, flavoring, and ¼ cup vegetable oil and whirl in a blender.

Once you’re mastered vanilla, you will want to try these quick and easy flavor variations.

BRANDIED CHERRY ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe: add 1 ½ cups pureed fresh dark sweet cherries to the cream mixture just before freezing. Omit the vanilla and add ½ teaspoon almond extract and ½ cup kirschwasser, or cherry, or chocolate cherry liqueur.

BURNT ALMOND ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe: substitute light brown sugar, lightly packed, for white sugar. Toast 1 cup blanched, chopped almonds in a 350°F oven until golden and add when ice cream is mushy.

BUTTER PECAN ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe: add to the mushy ice cream ⅔ cup chopped pecans that have been sautéed in 3 tablespoons butter until golden.

CARAMEL ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe: melt the sugar called for in the recipes in a heavy skillet until golden. Carefully pour in ½ cup boiling water. Stir until dissolved and boil for 10 minutes, or until thick. Add to hot cream mixture.

CAROB CHIP ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe: add 1 cup finely chopped carob nuggets to cream mixture just before freezing.

CHOCOLATE ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe: melt two to six 1-ounce squares of bitter or semi-sweet chocolate (depending on personal preference) in a small pan over low heat and add to scalded milk. Increase sugar to taste, usually doubling the standard quantity.

CHOCOLATE CHIP ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla or Vanilla Custard Ice Cream recipe: add 1 cup finely chopped chocolate chips to cream mixture just before freezing.

COFFEE ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe: add 3 tablespoons instant coffee, espresso, or grain beverage dissolved in 4 tablespoons hot water, or ¾ cup brewed coffee to cream mixture just before freezing.

COFFEE-WALNUT ICE CREAM

To Coffee Ice Cream, add ¾ cup chopped walnuts when the ice cream is mushy.

FRUIT ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe: add just before freezing 1 ½ cups fruit puree stirred with 2 teaspoons fresh lemon juice to heighten flavor and 2 tablespoons sugar or 1 tablespoon honey.

Use fresh or unsweetened frozen fruit such as strawberries, peaches, apricots, cherries, blueberries, raspberries, blackberries, mangoes, or plums. If you use pineapple, be sure to use canned, not fresh, pineapple. Fresh pineapple contains an acid that breaks down proteins, including milk protein, and will keep your ice cream from hardening properly. Fruits with seeds such as raspberries or blackberries should be drained after pureeing.

GRASSHOPPER ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe: add ¼ cup each green crème de menthe and crème de cacao to chilled cream mixture just before freezing.

MAPLE-WALNUT ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe: use ½ cup pure maple syrup for the sweetener and add ¾ cup chopped walnuts when ice cream is mushy.

PECAN PRALINE ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe: lightly coat an 8-inch cake pan with vegetable oil and put in 1 cup chopped pecans. In a heavy skillet, slowly melt ½ cup sugar with 1 tablespoon water, stirring occasionally, until the mixture turns a light brown. Pour over the pecans. When the caramel has hardened, break it into very small pieces. Add to the ice cream when mushy.

PEPPERMINT CANDY ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe: add ¼ cup crushed peppermint stick candy to the milk while it heats, stir until dissolved. Add 1 teaspoon peppermint extract to chilled cream mixture. Stir in ¼ cup crushed peppermint stick candy to ice cream mixture when mushy.

PISTACHIO ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe: add 1 teaspoon almond extract with the vanilla extract. Add 1 cup finely chopped pistachio nuts when the ice cream is mushy. If you want green ice cream, add several drops of green food coloring with the extracts.

ROCKY ROAD ICE CREAM

To any Chocolate or Carob ice cream: add ½ cup chopped nuts and ½ cup marshmallow bits to ice cream when mushy.

RUM-RAISIN ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe: soak ⅔ cup raisins in rum to cover until plump. Drain and dice raisins. Add rum and diced raisins to ice cream when mushy.

SWIRL ICE CREAM

To the Basic Vanilla Ice Cream recipe or another appropriate recipe: remove dasher after freezer stops. With a knife or narrow spatula, stir in 1 cup thick dessert sauce or jam just enough to create a swirl effect. Use dessert sauces such as caramel, butterscotch, blueberry, carob, chocolate, or marshmallow, and jams such as strawberry, blackberry, raspberry, peach, apricot, or apple butter.