When planting seeds, we gardeners operate within countable numbers — say, 25 seeds for a planting of squash, or a few hundred for a nice row of zinnias or beans. But most garden weeds produce so many seeds that it’s a small exaggeration to call their version of seed production a seed rain. In a good year, a healthy crabgrass plant can drop 100,000 seeds, and lambsquarters can beat that number five times over. Along with amazing numbers, weed seeds (and the roots of tenacious perennial weeds) have an almost supernatural gift of longevity. For example, if you were to bury an assortment of weed seeds a foot deep and leave them there for five years, when you finally brought them to the surface you could expect about 25 percent of them to sprout. Try the same experiment with seeds of cultivated onion or lettuce and germination will be zero.

All gardeners can assume that every square inch of their garden soil contains weeds. Some of them may have been there for years, while others dropped or blew in only yesterday. The seeds that exist naturally in any soil are called the soil’s seed bank. And just as with the dollars in your checking account, repeated withdrawals will make the balance go down. If no deposits are made (by allowing weeds to drop seeds or importing weed-seed-bearing manure or topsoil, for example), you can make your balance go lower and lower — maybe by as much as 25 percent a year in the first three years. But you will never completely bankrupt your soil’s weed seed bank, for some seeds will always blow in or perhaps hitch a ride on the feet of a passing bird.

To drive the balance in your soil’s weed seed bank close to bankruptcy, the most important thing to do is to prevent weeds from shedding their seeds. Use mulches, cover crops, smother crops, cutting and mowing, hoeing, and hand weeding to keep weeds from developing and shedding seeds into your garden soil. Where weeds are allowed to grow and reproduce freely, about 95 percent of the weed seeds in the bank come from weeds that shed seeds in previous seasons.

Some gardeners are reluctant to use manure to enrich their soil for fear that it contains many weed seeds. Yet the number of weed seeds in manure depends on what the animals eat and can be very high or close to nothing. As long as the animals that produce the manure you put in your garden do not subsist on weeds, you can use the manure with confidence to improve your soil’s structure and fertility. Also keep in mind that it’s easier to control weeds than it is to grow healthy flowers and vegetables in weak, infertile soil.

Many weed seeds are extremely tiny. All seeds contain food energy that the new sprout uses for its initial growth, and the tinier the seeds, the fewer food reserves the plants have to sustain them during and just after germination. So how do plants that are handicapped by minuscule seed size survive? They take the energy they need from the sun.

Here are several ways to deny weed seeds the light they so desperately need:

1. Resist the temptation to overhoe. Avoid constantly turning up the soil so that new weed seeds (which were previously buried) are close enough to sunlight to take advantage of its energy. Sunshine cannot help seeds that are buried deep, so hoeing or cultivating only the very top of your soil will result in fewer weed seeds germinating than if you were to go deeper, and thereby drag weed seeds up into the “germination zone.”

2. Mulch your soil. Mulching exposed soil also limits the life-giving sunshine small-seeded weeds need, as does maintaining a thick canopy of foliage over the soil. Scientists have found that one of the reasons fewer weeds emerge from soil that is partially shaded by plants is that a foliage canopy changes the type of light that filters through. In other words, it’s not just weed plants that are set back by shade; many weed seeds require bright unfiltered light to trigger germination.

3. Provide shade. The constant shade of nearby plants may also keep some weed seeds from germinating by limiting changes in soil temperature. The daytime warming and nighttime cooling that take place in open soil encourage the germination of some weed seeds. Shade decreases those temperature changes, which also helps reduce the number of weed seeds that come to life.

New annual weeds usually sprout from seeds, but hardy perennial weeds have other ways of making sure they stay alive. True, long-lived perennial weeds like bindweed and johnsongrass produce seeds, but they’re usually small or relatively few in number. Instead, many perennial weeds reproduce vegetatively, without flowers or seeds, or by producing seeds as an afterthought. For example, new quack-grass plants can sprout from bits of root; nutsedge and wild garlic grow from corms left behind in the soil when the mother weed is pulled; and bermuda-grass and john-songrass sprout from pieces of rhizome (a sort of stem-root structure) that become brittle and break off when you try to dig out the plants.

Wild garlic (Allium vineale)

These vegetative plant parts often succeed at reproduction where seeds fail because they contain substantial food reserves to help tide the new plant over until it’s ready to stand on its own. Most weeds capable of multiplying by spreading vegetatively and by making seeds take care of first things first: They develop aboveground runners or underground buds (or rhizomes or corms) before they attempt to flower.

Keep this in mind when managing weeds that spread into colonies. Although you might wait until flower buds form on annual weeds to chop them down, attack spreading perennials early and often to make sure you don’t work any harder than you really need to.

Weeds find much of their strength in numbers, which is the main strategy they use to take over your garden. In addition to the seed-production bonanza that allows them to self-propagate successfully, many weeds have evolved to grow as ferocious competitors or resource-stealing companions to the “good” plants that we often cultivate.

The most successful weeds are closely keyed to the cultural sequence of certain crops, almost as if they are natural partners. For example, the pretty flower called bachelor’s button (Centaurea cyanus) joined the ranks of weeds in Europe 300 years ago (and more recently in the Pacific Northwest) since it became an unwanted companion to winter wheat. Bachelor’s buttons like everything about winter wheat — the time it is planted, the soil in which it grows, and also the way it is harvested.

Scientists call this near perfect fit between weeds and cultivated plants crop mimicry. Perhaps you’ve seen mimicry at work in your garden when you thought you were growing a wonderful tower of pole beans, only to find morning glory vines overpowering your beans one day. Get to know any and all resident weeds that have this trick up their sleeve and focus your control efforts on them before they bamboozle you.

As you become a seasoned gardener, you will gradually become an expert at recognizing the seedlings you want to grow, as well as your weeds. This does not happen overnight. The truth is that some weeds look like cultivated plants, which is part of their self-preservation strategy. Shirley poppies look like dandelions, lambsquarters can look like radishes (at least for a while), and sorrel looks a bit like spinach. If you’re new at this who’s-who-of-weeds game, delay weeding until you see a pattern in the plants, instead weeding around the row you planted. With time, recognizing the true forms of weeds and cultivated plants will be automatic.

Besides great timing, weeds use other strategies to assure themselves of long, prosperous lives. The most successful weeds grow so fast that they have no trouble stealing the space, light, nutrients, and water that we hoped would go to our lettuce. Crabgrass, one of the fastest-growing plants on the planet, is a prime example.

Some weeds are downright detrimental to other plants. They exude chemicals from their roots that act as poison to other plants, or perhaps they “sabotage” the site in other ways. Nutsedge hosts soil-dwelling bacteria that destroy soil-borne nitrogen, the most important nutrient for most growing plants. Bermudagrass roots give off chemicals that slow the growth of other plants, including peach trees. This plant-to-plant chemical warfare is called allelopathy.

Several weeds provide textbook cases of allelopathy in action. When lambsquarters starts flowering, the roots release toxic levels of oxalic acid into the soil. Velvetleaf carries toxic substances to its leaves, which rain then washes into the soil. Scientists are now confident in saying that several weeds — quackgrass, Canada thistle, johnsongrass, giant foxtail, black mustard, and yellow nutsedge, among others — hinder other plants while they are alive through competition for resources and allelopathy, and after they are dead by releasing plant-killing chemical residues.

Smooth crabgrass (Digoitaria ischaemum)

Some weeds go even farther by enlisting the cooperation of soil-dwelling bacteria in an attempt to keep other plants from crowding their space. Ragweed, crabgrass, prostrate spurge, and some prairie grasses may be able to counteract the work of rhizobium bacteria, the soil-dwelling microorganisms that help legumes (like peas and beans) fix nitrogen from the air.

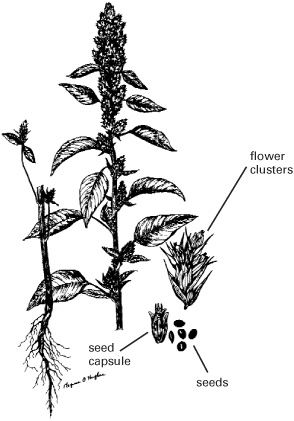

Redroot pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus)

Perhaps you’ve noticed that when gardening conditions take a turn for the worse — during droughts or plagues of grasshoppers, for instance — weeds tend to fare better than cultivated plants. This edge cannot be attributed to allelopathy. Cultivated plants like beans and corn have been selected over hundreds of years to grow in the pampered sites of gardens and cultivated fields, where they are lavished with good soil, generous spacing, and supplemental water. Weeds, on the other hand, growing wild and untended, have developed very large root systems that may be measured in feet rather than inches. While bean roots may reach down a foot or so, the deepest roots of redroot pigweed grow down three times as far!

This is both good and bad. In light of the primary mission of most garden weeds — to heal over and restore open soil — deep-rooted weeds not only survive but also pull nutrients from deep in the subsoil up to the surface. But it’s bad news for gardeners, since weeds constantly interfere with the welfare of our plants. All gardens have weeds, and all good gardeners must find ways to get rid of them.

Getting to know the weeds that inhabit your garden space is crucial to reducing their numbers. First we’ll look at large-scale measures that have a broad impact on all weeds — methods that can shrink the balance in your garden’s weed seed bank in a big way. These methods include cover cropping, using smother plants, and mulching.

Weeds are naturally discouraged when the soil is well covered with healthy plant life. Plants that can be used to temporarily or permanently cover arable ground are called cover crops. Some cover crops are allowed to grow and are then mowed down or turned under, while others can be used as permanent companions for vegetables and fruits. Either way, cover crops discourage weeds and help improve the soil at the same time.

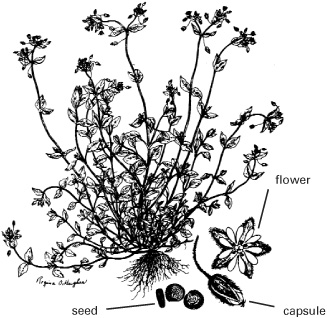

Common lambsquarters (Chenopodium album)

You need to think through how you intend to use cover crops to make them really work for you. Grain-type covers, such as annual rye, cereal rye, and wheat, produce a huge amount of top growth, and the roots tend to be quite extensive, too. For these reasons, it’s impossible to plant a crop into an established stand of uncut grain. However, you can allow the grain to grow from fall to spring and then mow it down and allow the stubble to dry where it falls. To plant in this dry mulch, open up a small space here and there and plant in those open hills. Vine crops such as watermelon, cantaloupe, and sweet potatoes often do very well when grown this way.

Some cover crops grow best during the winter months, flower in spring, and then cease growth through much of the summer, just when you want to use the space to grow vegetables. The best example is the subterranean clover (Trifolium subterraneum), a European legume. Subterranean clover does not grow and spread during the summer months as most other clovers do, so it’s an ideal cover crop for places where you will grow summer crops like corn. In a study done in New Jersey, a cover crop of subterranean clover controlled morning glory and weedy grasses in corn better than herbicides, and slightly increased the corn yield to boot!

You can even use weeds themselves as cover crops, provided you turn them under before they have a chance to develop viable seeds or mow them so often that flowers never have a chance to develop. For example, let’s say that you cleaned out the bed where you grew spring lettuce and three weeks later found a strapping stand of pigweed, lambsquarters, and other weeds in its place. If you let these weeds grow for a few weeks and then turn them under, you can consider that space cover-cropped.

Many people who grow large gardens plant their crops in wide rows and keep the walkways between the rows in mixed cover crops, such as a mixture of white clover, red clover, and buckwheat. The cover-crop rows serve as a habitat for spiders and other beneficial insects, and the clovers help enrich the soil by fixing nitrogen from the air. As long as these between-row stands remain thick, few weeds are able to grow there.

Of course, you don’t get habitat for more than a dozen beneficial insects without putting some work into this plan. Depending on rainfall, you will need to mow the cover-crop rows (usually about once a month). The cover clippings make excellent mulch, however, and if you use a mower that throws the clippings out a chute on the side, you automatically mulch adjoining crop rows as you mow. To make sure your beneficial insects always have a place to go, try to mow only some of the mixed cover-crop rows on a given day, or, better yet, plan your mowing so that alternating rows are mowed in alternating weeks.

You can use cultivated plants to smother out unwanted weeds, too. This method consists of sowing a specially selected companion crop that forms a weed-suppressing ground cover beneath your crop plants. The only trick is to provide enough water for both the primary crop and the smother crop.

Ideally, a smother-crop plant should have these four characteristics:

1. Fast-sprouting, so it will come up at least as fast as the weed it’s supposed to smother.

2. Broad-leaved, so that leaves spread horizontally over the soil’s surface will shade out weed seeds trying to sprout or weed seedlings trying to grow.

3. Short in height, so it won’t get taller than crop plants and shade them out, too.

4. Shallow-rooted, so it won’t seriously compete with the crop plants for space, nutrients, and water.

Agricultural scientists are starting work that may result in a new generation of plants specifically designed to work as smother crops, but for now gardeners can think in terms of lettuce, mustard, and other leafy greens, as well as fast-growing bush beans and field peas. None of these are exactly right for the job. Lettuce often sprouts slowly, most leafy greens grow upward instead of outward, and beans and peas eventually get quite tall. Yet you can help with these shortcomings. For example, you might broadcast turnips a week ahead of summer squash but basically grow the two together. The squash will quickly overtake the turnips, but it will take a while for weeds to do the same — especially under the dark canopy of big squash leaves.

When investigating the use of short-lived smother crops to control weeds in corn, scientists in Minnesota thought yellow mustard might do the trick. However, they found that when the corn and mustard were planted together, the mustard grew so quickly that the corn had to compete with it, and yields suffered. But if the mustard had been planted two weeks after the corn, the corn would have gotten the head start it needed, and the story may have had a happier ending.

The Minnesota scientists did learn that yellow mustard suppressed 66 percent of nasty weeds, which included yellow foxtail, green foxtail, lambsquarters, and redroot pigweed. If you translate this idea into a scaled-down version for a small garden, you might substitute a leafy green that you intend to eat young, such as arugula (also known as rocket), and plant it just after sunflowers or another tall crop. Instant edible smother crop!

In my spring and fall gardens, I routinely use lettuce as a smother crop, interplanting it with broccoli and always alongside peas. If left unsmothered, the open soil in the beds would be overrun with chickweed, henbit, and wild violets. With the help of lettuce (especially fast-growing leafy types), I must weed my spring garden only once or twice, and always get two crops instead of one from a limited amount of space.

In warmer weather, you might use other plants as smother crops. I often sow crowder peas in unoccupied beds in midsummer and thin back the stand (by pulling out individual plants) before sowing late crops of carrots, beets, parsley, and other vegetables that have a hard time sprouting when the days are so hot that the soil heats up and dries out daily. The shade from the legumes helps keep the soil moist enough to facilitate germination. When the carrots or other crops attain the status of sprouts, I pull out the rest of the peas, which all the while have been fixing nitrogen in the soil and suppressing weeds.

Almost all weed seeds need light to germinate and grow. Light functions like a trigger to some weed seeds that wait in the soil for years, deactivated by darkness. Mulches control weeds by depriving them of life-giving light.

The best mulches for suppressing weeds are the ones you already have. In fall, spread chopped leaves over empty beds to keep chickweed and henbit at bay. If you run over the leaves with a lawn mower before you pile them on your soil, they will sufficiently decompose over the winter so you can simply turn them under in spring. Stockpile extra leaves to use around garden plants during the summer months.

Pine tree needles are useful, too, though they are acidic and tend to help naturally acidic soil stay that way. Use them to discourage weeds around plants that like acidic conditions, such as strawberries, azaleas, and rhododendrons.

Environmentally minded lawn-keepers are advised to let grass clippings rot where they fall, but they also make great mulch. I hook the bagger on my mower when I cut my backyard; then the clippings go straight from the bag into flower beds.

You can go for years without buying mulch materials, but in the end weathered wheat straw may be worth its modest price. Unlike hay, which usually contains zillions of weed seeds, wheat and oat straw are normally pretty clean. If you can find some that’s been rained on (so its value as animal food is low), buy it. Besides suppressing weeds by depriving the seeds of light, wheat and oat straw are believed to leach out chemicals that act as natural herbicides. But as long as you use them to mulch plants that are beyond the seedling stage (such as established berries or transplanted tomatoes and peppers), wheat and oat straw both have strong track records of increasing yields.

Leaves, grass clippings, straw, and other materials that rot are called organic mulches, and the material they eventually become — called humus — is nature’s most fundamental soil conditioner. Yet these organic mulches do have a flaw when it comes to weed control. Some weeds can grow through them, a feat that becomes easier as the mulches compact, wear thin, and decompose.

You can enhance the weed-controlling ability of any organic mulch by placing sheets of newspaper or cardboard beneath it. Lay down two to six sheets of newspaper directly on the ground, or cut cardboard boxes to make them flat and spread them over the soil in a single layer. Top off these paper mulches with leaves, grass clippings, or straw. Newspapers can also help stretch your mulch supply, since you’ll need only about a 1-inch-deep blanket of organic mulch instead of a 3-inch one (the usual depth required to keep weed seeds in the dark).

Mulching materials are usually easy to find in gardening centers. Many stores offer several different types, including the following:

Woven black or green polyester fabric mulch (such as the product called WeedBlock) are the most expensive kinds of roll-out mulches to buy, but they are long-lasting and work just great. Water and air pass through them, but the openings are too small for weeds. A good-quality fabric mulch will last several seasons when used in shade or when protected from sunshine with an organic mulch. Gardeners who like their gardens to look extra neat and manicured love these products, and often cover them with bark nuggets or pine straw for a more natural look.

Spunbound black polyester mulches (such as Weed Barrier Mat and Weed Shield) are as easy to use as the woven types, and about as long-lasting when protected from strong sun. Tearing can occur when used in places that get heavy foot traffic. The cost is slightly less than the woven version.

Perforated black plastic is widely available at discount stores. It’s basically heavy black plastic with little holes punched into it for rain to trickle through. Hot sunshine causes the plastic to degrade, so without a topping of organic mulch, the stuff is good for only one season. Relatively inexpensive, this type of mulch heats up the soil below it, so it’s better in cool climates than in hot ones. An extra plus is that little soil moisture evaporates through the plastic, so you have to water less often.

Roll-out paper mulch (such as BioBlock) degrades over the course of a season, so you never have to pick it up — just till it under. When topped with an organic mulch, paper mulches perform beautifully, without the disposal problems of plastic. The cost is modest as well.

Weeds are terribly hardy creatures. Despite all the hard work you may put into preventative measures against them, there will be weeds in your garden. Whether you hoe or weed by hand, you’ll be getting to know the weeds in your garden personally, one by one.

Hoeing can be done standing up, but most hand weeding requires you to squat, kneel, or sit while you get the job done. My preference is to sit, and I do it on a dense foam pad that I’ve had for years. A neighbor uses an old stadium seat, and the garden catalogs sell kneeling pads made especially for this purpose. All weeders need one of these or something equally effective, both to keep their clothes clean and to make weeding easier.

Herbicides are chemicals that kill plants. Conventional farmers rely on them heavily, but gardeners are better off using them only for emergencies. It’s a purity issue, for all chemical herbicides are highly toxic and definitely do not fit into the descriptive category of “earth safe.”

You will not find me recommending so-called natural herbicides, either, for I have been disappointed with how well they work. Spray-on organic herbicides are basically soap sprays, and they do manage to kill the top parts of young seedling weeds. However, they are useless against older plants, and even young treated weeds often manage to grow back from their uninjured roots. Considering the time involved in mixing and applying these products, their short-term benefits, and the ever-present risk of injuring nonweeds, I think they’re a poor substitute for more traditional methods of weed control such as hands-on weeding.

Old-time methods of chemical control involving salt and vinegar aren’t safe, either, for they destroy many soil-dwelling microcritters and may make soil unfit for plants. For weeds, there are no environmentally safe miracle cures that come in bottles.

What are you to do with your weeds once you get them out of the garden? Young weeds often can be laid on the surface of the soil, where they will dry into mulch, or you can chop them into your compost heap when they are succulent and green. But watch out if the weeds are already in flower, even if you don’t think they are carrying mature seeds. Some weeds, like chickweed and purslane, can continue to develop seeds after you pull the plants from the soil.

Some of the toughest weeds have a miraculous talent for surviving the heat and stress of the hottest compost heap. However, these same weeds may be dried to death and then composted after they are thoroughly dead. Here is a drying method that may work for you.

First, pull out the troublesome weeds. Pile them loosely in a wheelbarrow and park it in the sun for a day or two. If rain is expected, move the wheelbarrow to a dry place (such as a garage) so the weeds won’t get wet. Then dump the weeds in a pile that cooks in the sun and never gets watered. In rainy weather, you can stuff the weeds into a black plastic bag.

To make sure the plant parts are thoroughly dead, spread them out and wet them down. If you see no signs of life, chop a mix of these nastiest of nasty weeds into your compost heap.

Common chickweed (Stellaria media)

If not strictly disciplined, some cultivated plants spread so much that they become pesky weeds. You can restrain their exuberant growth in several ways, but you still have to keep a close watch on them.

Some can be kept in place by growing them in containers partially sunk into the ground, with the rim an inch or two above the soil to keep the roots from spreading. Others, like mint, are best grown between a wall (or paved area) and a space that is regularly mowed. Tall spreaders like Jerusalem artichoke and tansy are best handled by planting them far from closely managed beds in areas where they can dominate other weeds rather than cultivated plants.

Here are 14 notorious spreaders and suggestions for handling them — provided you want them badly enough to put up with their invasiveness.

Crown vetch (Coronilla varia)

An excellent ground cover for steep, eroded banks, crown vetch becomes a monster when grown in or near pampered places like gardens. It spreads via seeds and fleshy underground stems, some of which are more than 6 feet long. Avoid planting crown vetch on banks that slope toward your garden. Slopes that end at a street or ditch are more suitable sites.

Honeysuckle (Lonicera spp.)

This plant’s wonderfully fragrant blossoms come at a cost — runaway growth that requires a commitment to trim and prune at least twice a summer. Even well-behaved named cultivars of bush-type honeysuckles bear close watching. The trailing types demand a place of their own. If allowed to mingle with other plants, they insist on strangling their neighbors.

Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus)

Grown for its nutty-tasting edible roots, this perennial sunflower dominates space with its height (up to 9 feet) and by seeds and sprouting roots. Never till over a dormant cache of roots, or you’ll spread them everywhere. Dig all roots from the outside of the colony yearly, in early winter, to keep the colony from getting too huge.

Mint (Mentha spp.)

The mints spread via ropelike creeping underground roots, called rhizomes, which can sneak several feet — even under thick mulch or concrete. Grow them adjacent to mowed areas so you can enjoy the fragrance of the cut leaves where you mow. Or grow them in large containers and cut back the faded flowers to keep the plants from dropping seeds. Some strains are better behaved than others.

Morning glory (Ipomoea hederacea)

In warm climates, the same annual morningglories that are breathtakingly beautiful on a trellis can become very pesky weeds as they twine around any other plant that’s upright. Grow them far from vegetable and flower gardens, preferably surrounded by a large area of mowed grass.

Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris)

This herb is valued in fragrance gardens for its camphorlike aromatic foliage, but it’s a rampant spreader that will quickly overtake other plants. Monitor new seedlings and young plantlets that pop up on the outside of the clump. Promptly pull up the ones you don’t want. Cut back plants as soon as they flower to keep them from dropping seeds.

Oxeye daisy (Chrysanthemum leucanthemum)

This lovely wild (but non-native) daisy can become a nuisance, especially in the Northwest and Midwest. But in most places, you can control oxeyes by mowing or hoeing out unwanted plants. If you like the daisies but not where they’re growing, dig them early in spring and move them to your chosen spot.

Purple loosestrife (Lythrum Salicaria)

A dramatically beautiful perennial, purple loosestrife has become such a problem in the wetlands of the upper Midwest that its cultivation there is now illegal. Until reliable sterile strains become commercially available, choose something else for your garden, like a nice monarda.

Snow-on-the-mountain (Euphorbia marginata)

One of the largest and showiest members of the spurge family, snow-on-the-mountain spreads via seeds and has become a resented weed in parts of the Midwest. The leaves are poisonous to livestock, and the milky sap causes skin irritation, so handle with care. A much smaller Euphorbia, cypress spurge, is often grown as a ground cover and can become invasive if its spread is not controlled by the gardeners who grow it.

Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare)

Although tansy is useful for attracting beneficial insects (and possibly repelling destructive ones), it rapidly gains dominance over other plants with its tall, robust stems, and then produces thousands of seeds. Cut it back after the flowers have hosted their mini wasp party, and promptly dig out plants that pop up where you don’t want them. Better yet, grow tansy in containers so you can move it around and let different plants enjoy its beneficial aura.

Toadflax (Linaria vulgaris)

Also known as butter-and-eggs, this delicate little wildflower sometimes gets carried away with itself, especially in northern areas where cool weather enables it to set seeds very successfully. Plant in impoverished soil where other plants refuse to grow.

Trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans)

When properly managed, this perennial woody vine is a fine addition to a low-maintenance landscape. To limit its spread, clip off all the green seedpods you can reach before they are fully mature. Prune as needed to confine the vine to its allotted space in your garden.

Violet (Viola papillionacea)

There are good violets and bad ones, and the common blue violet of the eastern United States is too naughty for cultivated space. Pretty flowers in early spring are no excuse for the tenacious roots of this native species or the way it reseeds so heavily that it smothers out nearby plants. Have no fear of the better-behaved violets, like Johnny-jump-ups and yellow violas, or the native birds-foot violet.

Yarrow (Achillea millefolium; Achillea Filipendulina)

Both species of yarrow are enthusiastic spreaders, so keep a close eye on them. Cultivated forms of both species are prettier and better behaved than the strains often sold as wild-flowers, but they still need to be monitored. Pull up or dig out unwanted plants. When mowed twice a year, Achillea millefolium can make a nice ground cover.

These days the healthiest gardens are all abuzz. A garden teeming with insect life is a sure sign of a well-balanced miniature ecosystem. Impossible under the rain of pesticides and insecticides often accepted as “conventional” pest controls, a varied population of insect life will benefit the garden as no spray ever could.

Of course, all gardeners have problems with insects at one point or another. The number of garden insect pests staggers the imagination. Flies, moths, and butterflies fill the air; cutworms, nematodes, and others choke the soil; and caterpillars, beetles, and a bevy of bugs try to invade everything in between. What’s a gardener to do?

The answer may be a surprising, nothing. Or at least as little as possible. Certainly don’t resort to toxic chemicals. For while they may kill off a large number of bugs in one fell swoop, you might be surprised at the actual cost of such control measures. Not so much in dollars and cents, but the cost in contamination of food, soil, groundwater, and insect gene pools.

Chemicals are responsible for a great many modern ills, from increased cancer rates to birth defects. These chemicals often are not merely present on the surface of crops. Some are absorbed by the soil and taken up by the plants’ roots, which circulate the toxins throughout the plant, infiltrating the entire system of the plant. Chemicals not immediately absorbed by plants eventually make their way to the water table, into wells and other water supplies.

But contamination of food, soil, and water is not the only evil of toxic pesticide use. Wiping out complete bug populations can wreak more havoc on your plot than doing nothing to control them. Pesticides kill indiscriminately: the good die right along with the bad and the ugly.

There are also the inevitable reactions of resistance and resurgence. There are always a few survivors of a pesticide attack. These few quickly reproduce new generations, at least as well equipped to withstand chemical assault as their parents. Mutations occur through successive generations until invincible “superbugs” evolve.

At the same time, smaller populations of secondary pests find the competition suddenly eliminated. Not only the competition, but all the predators and bug parasites have vanished with them. Uninhibited, these secondary pests can become primary problems.

So what is a gardener to do? If you must resort to pesticides, opt for botanical derivatives, which break down quickly into harmless components, or try the many other organic remedies available, from pheromone traps to soap sprays to bacterial bug “bugs.” Never overlook the importance of sound cultivation practices, such as soil, weed, and water management. Try a “patchwork” garden, arranging plants into mixed beds or rows. This slows many a pest who prefers to munch his way down neat rows of his favorite fare. Handpicking bugs and eggs is a valuable practice—just be sure to familiarize yourself with those you find. You wouldn’t want to squish a friend!

One of the best methods is to take your cue from Nature herself, and employ “good” bugs against those “bad” pests. Encourage predators and parasites, as well as vital pollinators, by including a mix of flowers and herbs among your plantings. You may be in for a treat once beneficial insects come to your rescue. Some will help with pest-control problems, stalking and parasitizing your pests; others will help to improve crop production by pollinating plants; and still others will help to build ever healthier soil by adding organic matter and working the soil to improve fertility and drainage.

To list earthworms among the natural wonders of the earth would only begin to pay them due tribute. A single slimy, squirming worm in the hand may not seem like a living miracle, but the combined forces of trillions perform vital, literally earthshaping tasks every day, everywhere.

Earthworm bodies are virtual humus mills, manufacturing nutrient-rich castings (manure) from nearly anything found in the soil. As they burrow through the earth in their constant search for food, they leave tunnels that improve soil aeration as well as drainage and water retention. All this underworld activity also gives both subsoil and topsoil a thorough mixing.

Actually worms are not insects. They belong to a vast classification of animals called annelids, the ringed or segmented worms. The order Oligochaeta is but a fraction of this diverse group, to which the three thousand or so different kinds of earthworms belong.

The earthworm is a marvel of underground engineering, perfectly designed for his soil-dwelling role. Long, slender, and tapered at either end, the body is made up of many segments. Large night crawlers may have over one hundred fifty segments, while manure worms possess fewer than a hundred. These segments are formed of circular muscles, which make the earthworm incredibly strong for his size. In the course of a day he may shove aside many stones and other bits of debris sixty times his own weight.

The average North American garden-variety worms measure about 4 to 8 inches in length. Most are reddish in color, some with alternating yellowish rings, others are a deep maroon, and some even greenish. All are slimy, the result of a highly efficient kidney system that pumps out fluid wastes through pores located all along the body. This mucus helps them to glide through the soil. Worms have no eyes, though they are sensitive to light, and no ears, though most are unbelievably attuned to vibrations. Though earthworms have a tiny “brain,” it can be removed without any apparent effect. And earthworms have five hearts!

The worm’s existence is primarily one of digestion.

All of his essential organs are located in the front one-third of his anatomy, but his digestive tube runs the entire length of his body. An earthworm has the ability to regenerate a lost or injured tail, but contrary to childhood beliefs, the tail cannot regrow a new head.

Earthworms make their way through the soil by a combination of muscle contractions and by swallowing much of what lies in their path. Digestive fluids neutralize acids, raising the pH levels of acidic soils. The castings also tend to neutralize alkaline soil, which makes earthworms a valuable asset for balancing soils.

The worm’s organically rich castings are made up of essential, water-soluble nutrients, easily accessible by plants. Compared to topsoil they contain five times as much nitrogen, seven times as much phosphorus, eleven times as much potash, and three times as much magnesium. Noting that earthworms convert anything available into fertile manure, the Greek philosopher and naturalist Aristotle dubbed these creatures the “intestines of the earth.”

Each worm can recycle his own body weight daily. The concentration of earthworms varies from region to region, but estimates from one hundred fifty thousand to two million per acre are common. With each producing up to his own one or two ounces of body weight in castings every day, even if they were active only half the year they would still produce from 5 to 50 tons of instant compost per acre, per year!

Besides eating, a worm’s other primary function is reproduction. Any two worms can mate and reproduce because each has both male and female reproductive organs. Both sperm and eggs are released into a thick envelope of mucus, where fertilization occurs. Gradually, as the slime dries, it draws closed at either end into a lemon-shaped capsule.

From two to twenty eggs will hatch within two to three weeks. In two to three months they are mature enough to reproduce, doing so every seven to ten days—up to 1,500 worms each year per individual. A worm’s needs are simple—moisture, moderate temperatures (from 60° to 70° F. is optimal), oxygen (provided by their tunneling), and food (anything small enough to fit into their mouths). They avoid light; direct sunlight for more than a few minutes is fatal. Many come up to feed at the surface at night or after a rain, as the vibrations from falling raindrops alert them to the moist conditions.

Some species, like the common night crawlers, dig deep tunnels, converting and mixing subsoil as well as topsoil, and carrying bits of leaves or other organic debris down into the lower layers. Others work only the top few inches of soil, many rising to the surface to deposit their castings.

Supply plenty of organic matter, even by scattering or lightly burying biodegradable trash, such as kitchen scraps or newsprint; maintaining soil moisture to a depth of at least 2 inches; and avoiding the use of chemical pesticides. Provide protection from natural enemies such as moles, birds, snakes, ants, and centipedes.

Earthworms can be purchased from commercial growers to supplement or to start a population of your own. Buy capsules or just-hatched worms rather than full-grown breeders, as they are much more apt to adapt to new surroundings. Interestingly, when smaller species of worms are raised with larger varieties, the little guys will assume the identity of their neighbors and grow to a larger size, but only if raised with them from the hatching stage.

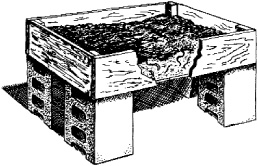

Vermiculture, or the raising of earthworms, is a worthwhile endeavor in its own right. Worms can be raised in anything from a shallow box to massive in-ground pits. All that is required is bedding material, food, moisture, darkness, and worms. A wooden box 1 foot deep, 2 feet wide by 3 feet long, with ½-inch holes drilled into the bottom for drainage and aeration, should serve the needs of a four- to six-person family. Fill the box with shredded cardboard, newspaper, or computer paper, or animal manure, leaf litter, or peat moss. Throw in a handful of soil or powdered limestone to provide grit, mix well, and wet thoroughly. Add two pounds of worms per pound of food (kitchen scraps, etc.) that you plan to have available per day.

Keep your worm box covered with a piece of black plastic, heavy fabric, or old rug to conserve moisture and block light. Bury your peelings, coffee grounds, bread crumbs, pizza crusts, leftovers, and other material every few days, rotating the feeding site each time. The worms will turn your trash into treasure!

Plant pollination is the single most important step in plant production. Without this essential function, no amount of watering, weeding, or feeding will produce a harvest. No matter how carefully you choose your seed or stock, no matter how diligently you cultivate, control pests, or pamper your plants, without pollination your efforts will truly be fruitless.

Pollination is the process by which plants propagate their species. It is the plant’s way of uniting male and female cells to produce the seeds which, in turn, become the next generation of that plant. It is one of the most important types of plant reproduction, though by no means the sole method.

Many plants have evolved other kinds of self-perpetuation, such as sending off runners, and man has devised other ways to duplicate plants he favors, such as root cuttings. Even so, many cultivated crops rely on plant pollination.

Pollinated plants produce both male reproductive cells, pollen, and female reproductive cells, ovules. These develop within an exquisitely specialized apparatus, called a flower. Some flowers are both male and female, while others are either all male or all female. Corn bears male pollen-producing tassels and female silks, on different parts of the plant. Some plants mature pollen and ovules at different parts of the plant. Some plants mature pollen and ovules at different times, making cross-pollination necessary. Other plants can pollinate themselves, transferring pollen among different blossoms, while others require entirely different cultivars (species of a related plant) to get the job done.

Pollination is complete once the male pollen has been transferred to the female ovules, resulting in fertile seeds. Only after the fruit sets can we tell whether or not the faded flower has performed its intended duty. Of course, certain garden crops (lettuce and other greens, broccoli and related cole crops, onions and other alliums, turnips, radishes, and carrots, to name a few) do not reach the flowering stage in many home plots. But pollination is vital if you want to have seeds for next year’s garden. Many gardeners let a few of their choicest plants flower and go to seed, carefully collecting, curing, and saving the seed for the following year.

Many catalysts are credited with helping plants accomplish their reproductive goal. Corn crops depend on the breeze. Certain types of cacti rely on nectar-feeding bats. Man will manipulate the process to his advantage to produce hybrids that excel in those qualities he prefers. Many factors affect whether pollination occurs. We can influence flower formation by adjusting temperature, water availability, and soil fertility, but none of these can assure the completion of this important process.

By far the most important of the pollinators for plants grown and harvested by man are insects. Honeybees are among the most renowned pollinators, but bumblebees, hover flies, wasps, butterflies, and other insects also contribute to this essential cause.

Honeybees (Apis spp.)

Busy bees gather nectar and pollen from more than 250 kinds of plants. As they work inside the blossoms, sticky globs of pollen grains cling to their hairy legs and bodies. When the workers move from one flower to the next, the male pollen is transferred to the female ovules, thereby pollinating the receiving plant. This relationship benefits both the bug and the blossom. For while the plants depend on the insects to complete their life cycle, the insects rely on the plants’ nectar and pollen to feed their colonies.

There are four species of honeybees, the most productive being the domestic Apis mellifera of which there are several races, including the popular German (or European) and Italian, as well as the notorious “killer” African bees. There are no honeybees actually native to the United States, however, only immigrants.

Honeybees are easily identifiable as amber-colored insects buzzing amidst flower blossoms. These are sterile female workers, who grow to about ½ inch in length. The males are larger and stockier, with oversized compound eyes that come together at the top of the head. Longer yet, but more slender than the males, is the queen. She is rarely seen outside the nest. All bees have short antennae, three pairs of legs (the workers bearing pollen baskets on the hind legs), and clear wings.

The population of a colony, or hive, may grow to as many as one hundred thousand bees, each the offspring of a single queen. She begins egg-laying in late winter, depositing her eggs in specially made “brood cells.” A virtual egg-laying machine, she will lay up to two thousand eggs daily during the warmer months.

The vast majority of eggs develop into the sexually undeveloped female workers who are the lifeblood of the colony, performing specialized tasks, intricately designed for the benefit of the hive. Bee colonies are highly organized, perfectly functioning societies. Besides the nurse bees tending the developing larvae, members of the queen’s “court” attend to her every need. Other workers are foragers, collecting pollen and nectar, or carpenters, building the wax combs that house the developing young and store food. Guard bees are posted at the hive entrance to keep away intruders. They are known to fan the entrance with their wings in hot weather.

All workers can sting, but can do so only once as the act results in fatal injury. The queen also stings, but usually only when fighting for her throne, and her life.

The population of the colony rises and falls with the seasons, reaching a peak in late summer and dwindling throughout the winter. Bees do not hibernate, but cold weather finds them clinging together in a ball for warmth.

The farther your garden is from a hive, the fewer bee visitors you may expect. Most foraging occurs within a quarter-mile of the colony, though when pickings are exceptionally poor the workers may venture out several miles. Poor foraging sites will be bypassed for more promising areas, but in general the bees try to keep their commute to a minimum. They have devised an ingenious system of body language, or bee dances, to direct other foraging members of the hive to the best gathering spots.

Some plants provide better bee fare than others, thereby inviting the pollinators to work among and around them. Alfalfa and sweet clover are sought after by bees and also produce good honey. Fireweed, mints, and black and purple sage are also attractive. Orchard blossoms draw thousands of workers as do mixed flower gardens and—possibly most importantly—wild flowers and weeds. Blossoms that hold little appeal to us may well be the mainstay of the colony’s diet when other plants are not in bloom.

Bees also need water, and will make use of an accessible water supply, especially in hot weather. Normally, the droplets of dew collected on plants is sufficient.

The most important consideration in maintaining a healthy working bee population is allowing them a poison-free workplace. Practice organic pest controls. Switch from chemical fertilizers and herbicides to animal manures, compost, leaf mold, and the like. Bees are very susceptible to insecticides. They may become lethargic or erratic, depending on the poison. Workers die out in the field as well as back at the hive. House bees have the sad task of moving the bodies of their fallen sisters out of the hive. As they push them out the hive entrance, piles of the dead will form near the base of the hive. Entire colonies may perish.

Commercial growers often ensure pollination of their crops by renting hives from professional beekeepers. The beekeeper maintains the colony and harvests the honey crop, while the grower benefits from the pollinators’ work.

Beekeeping is a rewarding hobby that can be practiced almost anywhere. A wooden hive, placed in a sheltered area and stocked with a queen and a healthy colony, will provide prolific pollination as well as many pounds of honey. See Starting Right with Bees, for more information on beekeeping.

Bumblebees (Bombus spp.)

Some species of bumblebee is native to almost anywhere on earth, from the cold northern Canadian slopes to tropical rain forests or isles. Dozens of species are found throughout the United States, and most of these are important pollinators of a variety of crops.

Bumblebees are instantly recognized as large, loudly buzzing, flying balls of black and yellow or orange fluff. Their large size, (some are over an inch long) and menacing buzz command respect and often a generous berth. Actually, bumblebees are relatively docile creatures, no more testy than most honeybees, but unlike their sisters whose sting results in fatal self-injury, bumblebees can sting repeatedly.

Social insects, as are other bees, bumblebees follow a less stringent regime. There are still distinct classes of drones, workers, and the specialized queen, but a Bumble queen never surrenders her life to become an egg-laying machine as does the Royal Honeybee. She continues to forage occasionally and is more intimately involved with her progeny than is her counterpart.

Bumblebees do not maintain year-round colonies; instead they vacate their nests each fall and establish new ones every spring. Young queens, hatched the previous autumn, strike out each spring, feeding on pollen and nectar to build up their strength. They carefully hunt for a suitable nest site, such as overgrown ditchbanks, forgotten garden corners, or untended flower boxes. Abandoned mouse runs are a favorite find. There the queen builds a wax egg cell, provisions it with pollen, and seals from eight to fourteen eggs inside. She continues to forage, storing extra nectar in wax honey pots to hold her over during bad weather. She will actually brood the eggs like a mother hen, resting on top and warming them through body heat generated by moving her wings.

The eggs hatch into tiny wormlike larvae within days. They develop rapidly, and soon spin cocoons within their sealed chambers to undergo their metamorphosis into adult bees.

As these larvae undergo their transformation, the Queen Mother prepares new nursery cells atop the pupating cocoons. When this first batch of workers emerges, they will help to care for the next, and so on, until the colony numbers hundreds of bees.

Cold weather signals that the end is near. The queen stops laying eggs. No more workers emerge from the nursery cells, only drones and new queens. After a time the entire hive dies out, except for the new queens who, having mated, carry the seeds of the next generation of colonies. They fly off in search of a sheltered spot in which to hibernate through the winter. Spring days awaken them to start the cycle again.

Bees have many natural enemies as well as diseases. Insect-eating birds and large robber flies attack them on the wing. Badgers, skunks, and other animals will dig them from their inground nests, eating both stored nectar and bees. Mice, shrews, and other small vermin invade the nest and desecrate the contents.

Though some bumblebees do develop the ungrateful habit of cutting away part of the flower to gather nectar, thereby avoiding contact with pollen or ovules and shirking any responsibility of pollinating the plant, the vast majority are indeed important pollinators. They flock to wildflowers and flowering herbs such as oregano and thyme. They will make use of manmade nests such as a 6-inch cube placed just beneath the soil surface. They even adapt well to live in a greenhouse where they will mate, nest, and carry out their normal life cycles.

Hover Flies (Family Syrphidae)

Following bees, the runners-up for Most Important Pollinators are the hover flies, or flower flies as they are also known. The adults feed on nectar and the honeydew secreted by various plant pests. Pollen is transferred among the many blossoms they visit as they make their feeding rounds.

Hover flies are tremendously accomplished fliers. Aptly named, they can hover in place while feeding, appearing to rest in midair, despite any breeze. Suddenly, they dart away, moving forward, backward, or to the side with equal ease and effortless grace.

At a glance many hover flies closely resemble small bees or wasps. Though some are solid dark colors, others sport the same bright, contrasting yellow and black bands as do many bees and wasps. Buzzing while they work, many even sound like bees. But, despite the superficial likenesses, there are many differences. Most common hover flies are smaller and more slender than bees. They have only two wings rather than the bee’s four. Unlike bees or wasps, hover flies do not bite or sting.

Much of the credit for their intricate flying abilities goes to their sensitive vision. Though hover flies are no more able to make out images than most other insects, their oversized eyes instantly recognize and interpret even the slightest movements. By quickly adjusting to any changes in their position relative to stationary objects, they can ride the breeze seemingly oblivious to its effects.

Though all hover flies feed on nectar, there is a weird and wonderful variety of larval feeding habits. Some larvae are scavengers, surviving on debris, plant residues, even liquid rotting animal manures. Some combine their beelike camouflage and scavenger tactics to coexist in beehives as resident housekeepers, feeding off the residues of the hive. Still others are significant insect predators, heartily downing aphids, mealybugs, and other soft-bodied bugs.

These useful flies will flock to flower gardens and can be easily enticed to those that include such favorites as cosmos, coreopsis, gloriosa daisies, dwarf morning glory, marigolds, spearmint, baby blue-eyes, and meadowfoam.

Wasps (Hymenoptera)

The category of wasps includes a diverse array of insects from the buzzing, stinging picnic pests to tiny, barely visible parasitic organisms. One common thread prevalent throughout this varied group, however, is that the adult forms feed on flower nectar. As such, many aid in the cause of flower pollination. Flowering herbs or small single-flowered blossoms are easiest for the smallest wasps to access, and are equally appreciated by even the largest of the bunch.

Like the hover flies, wasps will earn their keep by preying on the pest insect population.

Read more about them in the section on predators.

Butterflies (Lepidoptera)

Butterflies of many species regularly visit a variety of cultivated plants, including lettuce and strawberries. Some are pests, like the white cabbage butterfly, menacing cole crops as they deposit their eggs, which hatch into downy, green, destructive caterpillars. But others are aiding the cause of pollination as they add their own colorful animation to the flowers they grace.

One look at a nectar-feeding butterfly’s mouth reveals an instrument highly specialized for its task. Though there are hundreds of variations, the basic structure is composed of the proboscis, a tubelike adaptation used to literally siphon the sweet nectar from within the flower. Other mouthparts are greatly reduced, except for feelerlike labial palps.

As the butterfly approaches a likely-looking prospect, he may venture near, then abandon several possibilities before alighting on his choice. This is probably due to the fact that his large, bulbous, compound eyes are capable of making out clear images only up close: what looks like a tempting blossom from a distance may turn out to be a bit of litter once it comes into focus. Many butterflies have taste receptors in their feet, so they can further distinguish, upon landing, whether or not they have found their sweet reward.

Ultraviolet reflection, as well as flower color, plays a significant part in drawing the drinker to the nectar he seeks. Once alighted, blossom in sight, he gingerly approaches and inserts his proboscis into the neck of the blossom, all the way down into the nectar reserves of the flower. He may spend only a second or two, or savor a long, leisurely slurp. As he feeds, grains of pollen adhere to his hairy legs or underbody and hitch a ride with him to the next flower. Since butterflies often visit a regular circuit of blooms, they can be very effective in pollinating those they patronize.

To attract these lovely insects to your garden, include a variety of blossoms. See “Planning a Butterfly Garden.”.

Well-pollinated crops in fertile, humus-rich soil definitely have the edge. They are disease-resistant, productive, and a joy to behold. In general, they are even less susceptible to insect damage than less vigorous plants. Unfortunately, outbreaks of plant-eating pests can occur even in well-tended plots. But don’t despair. Help may already be lurking in the shadows.

While greedy garden pests gorge themselves on the fruits and veggies of your labor, just one link up the food chain are carnivorous cousins waiting to come to your rescue. Among the most potent of biological control agents are the natural enemies, the predators, of bugdom. They may be hunters, who consume their victims — eggs, larvae, or adults — on the spot, or they may be parasites, whose hatching larvae do in the various stages of garden villains. In either case, they are upstanding insect citizens and outstanding pest exterminators.

Ladybugs/Ladybird Beetles (Hippotamia convergens)

Most of us recognize the adult form of this gardeners’ darling, but true to insect form, the other stages of development bear no resemblance to the familiar adults. Adult ladybugs may well have inspired the endearment “cute as a bug.” Bright orange-red, rounded little beetles, they average about ⅜ inch long and are nearly as wide. Like all insects, they gad about on six legs, theirs being short, black, and spindly. Their red wing covers are decorated with a sprinkling of black spots, the number, size, and placement of which vary with the species. White markings embellish the shiny black thorax, or center segment. Their heads are also shiny black.

But don’t dare to compare the youngest maidens with the adults. Eggs laid on plants pestered by aphids or other ladybug prey may be mistaken for those of some despicable pest. Learn to spot the clusters of small, oval, bright yellow eggs.

Tiny, yellow, and black, multisegmented larvae hatch from these eggs and go through several stages, or instars, the last being the largest and the hungriest. Each larva may devour several hundred aphids, earning them the nickname “aphid wolf.” Within about twenty days from hatching, these plump, feasting larvae undergo a brief metamorphosis, from which a tender, pale adult beetle emerges. The bright color and markings develop quickly.

Adult egg-laying beetles can put away two hundred aphids per day. Their life expectancy is only a few weeks, but these mature insects produce several generations per season, ensuring a constant supply of hungry ladybugs.

Both larvae and adults are active daylight hunters. They will prowl the garden, especially plants targeted by soft-bodied pests; the adults will even take wing in their search for food. All this activity is one of the prime reasons that ladybugs have such high nutritional demands. Upon spotting their prey, the ladybugs grasp it with powerful jaws and consume it live. The habits of such prey as aphids, scale, etc., are such that large, nearly immobile groups are often found together. The ladybugs will stay in one place, gorging on their fill of pests, continuing on their endless search only after cleaning up the immediate infestation.

In the western United States, ladybugs migrate in the fall to mass hibernating sites high in the mountains. Eastern varieties may congregate under garden litter for the winter. Warming spring temperatures trigger the beetles to migrate and disperse. During most of the year, nearly every North American habitat can claim some native species of ladybug.

Invite the neighborhood ladies to make themselves at home in your garden by incorporating their favorite flowering plants into your landscape. Angelica, buckthorn, euonymus, and yarrow will entice them. Special favorites include marigolds (especially the dainty, single-flowered Lemon Gem variety), butterfly weed, and tansy. By tucking some of these in among crops susceptible to aphids and other ladybug fare, you can lure the beetles to potential trouble spots, effectively curtailing outbreaks before they start. Lemon Gem makes a pretty border plant and can be used to edge the garden plot or beds of vulnerable crops.

In times of sparse food supplies (for instance once the aphid or other pest populations are under control), help our ladybugs along with an occasional garden party. Commercial beneficial bug food supplements are sold under names like Bug Chow and BugPro, or you can whip up your own. Dissolve one part sugar into four parts water for a temporarily sustaining homebrew. These mixtures simulate the sweet honeydew secretions given off by aphids and many of the ladybug’s other prey. Sprinkling a few drops around the lower leaves of target plants may help to keep your gals from going hungry, or from straying. These sugar concoctions may also encourage mold growth on plants, so don’t overdo it.

A special consideration for ladybugs and certain other aphid eaters is ant control. Ants and aphids have a symbiotic relationship, each benefiting from the other. Ants protect and maintain aphid “herds” in return for the precious drops of sweet, sticky honeydew. They will attack any marauding beetles or larvae in defense of their flocks. Boric acid is an effective organic means of ant control. Sprinkle some along their trails. Sticky bands of tacky material, either homemade or commercial preparations such as Tanglefoot, placed around the base of plants, will protect them from climbing ants. Be sure to keep the barriers free from any debris the ants might use as a bridge, including each other!

Ladybugs are widely available through mail order from numerous seed and garden catalogues or from many garden supply centers. A pint contains about 7,000, enough to cover about 5,000 square feet. By taking some precautions, you can improve the odds that a good percentage of the beetles will remain in your garden.

Remember that the first impulse a ladybug has upon waking from her winter’s sleep is to migrate. Instinct tells her she must move on to find food. Spring warmth, rough handling, and hunger will all add to her restlessness.

If you just open the container and scatter them to the breeze, chances are you’ll never see them again. Instead, consider things from the ladybug’s point of view. Hose down the release area thoroughly prior to setting them free. This will create a cool, moist area. Release them in the cool of the evening to further lull them (remember, ladybugs are active during the day). Don’t toss them from the container, but gently place groups of them about the plants most in need of their attention. The less shaken up they are, the less likely they are to make a quick getaway.

Ground Beetles (Family Carabidae)

If you happen to see a large, ugly, black beetle scurrying for cover from the light of day, resist that urge to stomp it. Ground beetles are fierce enemies of the likes of slugs, snails, cabbageworms, cutworms, armyworms, corn earworms, codling moths, gypsy moths, Colorado potato beetles, flea beetles, aphids, mites, thrips, and other garden pests.

Of the twenty-five hundred known species, some exist almost everywhere in North America. Ground beetles are found in a variety of colors from shimmering, metallic purples, blues, greens, and bronzes to flat black. Built like a tank, the average ground beetle comes heavily armored by a hard shell, and many are ominously large.

The basic black Carabus nemoralis is a relentless hunter who grows to well over an inch in length and will grab onto prey many times its own size, including small children’s fingers. They stalk the night for slugs, snails, and other nocturnal pests, hiding out by day under rocks, boards, or in other sheltered spots.

Another common large ground beetle, Calosoma scrutator, has been dubbed the fiery searcher, both for his vivid purple, black, and green iridescence and for his merciless hunting technique.

Some other ground beetles are as tiny as 1/16 inch, but still are fearsome predators of the smaller nightlife.

Females of some species lay their eggs in carefully prepared hollows in the ground and actually stand guard over them while they incubate. As many as fifty eggs may be deposited together, or hundreds may be laid singly in prepared mud cells. The voracious larvae emerge within a few days to a few weeks, and immediately begin chowing down on garden pests. Each grub may devour as many as one hundred caterpillars before pupating into an adult. Feeding habits range from the gruesome to the dainty. Some species, such as the fiery searchers, revel in ripping their victims apart to get at the tender insides, while others merely puncture a small hole into the side of their prey and neatly suck out the contents.

Each year a new generation is produced, but various beetles may live from two to five years, hibernating in the soil or crevices through the winters.

Syrphid Flies (Family Syrphidae)

We already know about these good-guy flies in disguise, many of whom look like wasps or bees but harmlessly provide the vital service of pollination. But there’s more. These useful creatures work double time to make our gardens more abundant and prosperous. For while the adults are busy performing their important task, the larvae provide yet another valuable service.

Syrphid, or hover or flower fly, larvae are a diverse bunch, as previously mentioned. However, a significant group are active predators of small insects such as aphids, mealybugs, thrips, and leafhoppers. During its active juvenile life a single larva can consume up to one thousand aphids or other small prey.

Hatching from small, white, oval eggs throughout the growing season, the larvae are greenish to grey or brown. Like miniature slugs, they are fat little maggots whose bodies taper to the head. However, they have the benefit of short, stumpy legs (called prolegs, common among caterpillar-type larvae) to aid their mobility. Their mouth-parts feature tiny hooks with which they grab their prey and suck out the body fluids.

The larvae grow up to only ½ inch or so, heartily eating their way to full size. At this point, they pupate and undergo the metamorphosis into the adult. As winter approaches, those larvae who have entered the pupal stage remain dormant and hibernate through the winter.

Tachinid Flies (Family Tachinidae)

Found the world over, tachinid flies are important parasites of a variety of pests, including Mexican bean, Japanese, and other beetles; many caterpillars and cutworms; an assortment of bugs; and grasshoppers. Though many of the adults are humble nectar sippers, the larvae are ruthless carnivores, devouring their parasitized victims from the inside out.

Of the nearly thirteen hundred species found throughout North America, many resemble large, bristly houseflies. Shades of brown, grey, or black with faint markings are common. Size ranges from about ¼ inch to ½ inch long. They fly about searching for hosts in an identifiable “seeking” flight. Once alighted on plants, they hustle across leaf surfaces in their quest.

Females deposit eggs in a variety of ways, all designed to get them into a host. Some types scatter thousands of miniscule eggs on foliage where the host routinely feeds, with the hope that they will be consumed along with the pest’s regular meal. Others deposit their eggs right on the host, while still others make dead sure the job is done by puncturing the body of the host and inserting their eggs within. Once inside the host, the eggs hatch and the larvae develop by sucking the body fluids. Small stages even receive their oxygen through the blood of their hosts, while larger parasites resort to drilling air holes through the victim’s body, or similarly accessing its breathing tubes.

Wild buckwheat is a favorite of the adults, and a small planting should draw scores of these pest-control experts to your garden.

Green Lacewigs (Chrysopa carnea, et al.)

Delicate, demure lacewings flittering through the twilight sky, daintily sipping at flower nectar or nibbling pollen for their daily repast, belie the merciless predation of their youth. Lacewing larvae, whose raging appetites have earned them the alias “aphid lions,” relentlessly stalk and devour hundreds of aphids throughout their brief childhood. Other soft-bodied insects, such as small worms, mites, thrips, leafhoppers, scale, immature whiteflies, and insect eggs form part of the larvae’s diet.

Adult lacewings portray the essence of delicate frailty. Barely ¾ inch long, they are slender insects with long, threadlike legs and antennae. Their wings are so fragile and transparent that except for a shimmer of iridescence when seen at certain angles they seem nearly invisible. Only the lacelike pattern of veins is distinguishable, hence their common name. Colored a soft, pale green, with large, coppery colored eyes, they blend well with their surroundings.

Adults are night fliers and can easily be observed apparently struggling towards bright lights. Their flight is labored and oddly clumsy for such a graceful-looking creature.

Female lacewings fly to any suitable plant to lay their eggs. This is generally one infested with prey for her children-to-be. Realizing the voracious appetites her newborns will possess, she ingeniously designs her nursery to prevent cannibalism. Secreting a tiny spot of sticky goo from her abdomen, she quickly draws it up into a fine silken stalk, which dries and hardens instantly. Atop this isolated perch she deposits a single, pale, pearly green egg. Several dozen of these curious one-egg nests may be grouped together or randomly scattered throughout the foliage.

Within days the eggs hatch into miniature larvae resembling tiny dull brown alligators with giant piercing jaws. These little guys immediately set off in search of their first meal. By grasping their prey between powerful jaws, injecting digestive juices into their victims, then slurping up the liquefied innards, each hunting “lion” can put away more than two dozen aphids or similar tidbits daily. After two or three weeks of feasting, the larva spins a cocoon and undergoes the transformation into the elegant adult. During the summer an entire lifetime may take no more than one month, but as winter approaches, larvae and some adults take shelter and hibernate until spring.

Though new generations of egg-laying adults can be produced throughout the summer, lacewing populations may not survive a harsh winter. However, they are readily available through mail-order catalogues or garden supply outlets. When sent through the mail, they are most often shipped in a medium containing supplementary food, such as moth eggs, and a dispersing agent, like rice hulls, both for physical separation of the eggs and as an aid in releasing them. Considering that ten thousand lacewing eggs will fit into the well of a thimble, it is obviously helpful to make them physically manageable.

Place the lacewing eggs out in the garden as soon as they begin to hatch. Suppliers recommend one thousand eggs per 200 square feet of garden if infested, or per 900 square feet as prevention against emerging pests. Simply sprinkle the contents in and around susceptible plants, then monitor to see if the hungry larvae are keeping pests in check. Repeat applications are often advised.

Since the larvae will devour any soft-bodied pest in its path, they rarely go hungry. Adults, however, depend on a ready supply of pollen, nectar, or honeydew. You can entice them to stay in your garden by providing an assortment of blossoms, including angelica, red cosmos, coreopsis, tansy, goldenrod, and Queen Anne’s lace. When these kinds of food are in short supply, the population will dwindle either through migration, death, or reduced reproductive ability. By keeping an eye on their numbers you should be able to spot when a handout is warranted.

Commercial beneficial bug foods are available, or provide your own by sprinkling small amounts of one part sugar to four parts water here and there.

Praying Mantis (Family Mantidae)

Reverently poised upon a beanstalk, forelegs raised as if in prayer, the deadly praying mantis waits for an unsuspecting meal to happen within its reach. Even though aphids, beetles, various bugs, butterflies, caterpillars, leafhoppers, small birds and animals from frogs to shrews — even each other — are all acceptable fare, praying mantises alone will not put much of a dent in their populations. This is because despite their large size and menacing appearance, mantises are actually dainty eaters. They maintain a slow-paced lifestyle that requires less food than you might expect.

Suddenly, a caterpillar lumbers near and the statue-like mantis strikes. Enlarged, spine-covered forearms grasp the struggling insect as it thrashes about. One quick bite from the accomplished killer through the base of the victim’s neck area severs crucial nerves, effectively paralyzing the prey.

Slowly, delicately, as if relishing every morsel, the hunter enjoys her meal, eating it alive.

Mantises, by their sheer size and strange appearance, are fascinating to watch. Unhurried, they generally allow the interested observer a fulfilling view. Their long, slender bodies may grow a full 5 inches or more in length. They have huge, bulging eyes and swiveling heads, the better to see approaching prey; powerful, spiny forearms, the better to grasp and hold it; and strong, chewing jaws, the better to consume it. Most come in shades from off-white to pale brown or green, which serve to blend in against the background. Not only an asset to their passive sit-and-wait hunting style, this camouflage helps to make them less obvious to birds and others eager to prey on so large and slow a meal.

When old enough to mate, the male mantis must question at some point whether it is really worth it. The female simply regards him as nothing more than a potential meal, and he must proceed with extreme caution if he is to accomplish his goal intact.

Upon spying his ladyfair, the suitor freezes in his tracks. Ever so slowly he approaches her from behind, taking over a half hour to move only inches. When finally he is close enough, he hops up and clasps his betrothed in a mating embrace.

If, however, the female sees him or is disturbed in the process, she will turn on him and literally bite his head off! Interestingly, this does nothing to impair the decapitated male’s mating ability, and he continues to engage his mate until the act is completed. At this point, the now fertilized female devours the unlucky fellow, requiring him to satisfy her hunger as well.

Of the eighteen hundred species, many occur throughout the United States, most being relatively coldhardy. Females lay as many as one hundred eggs in foamy, sponge-like egg cases that they create and deposit on branches or suspend from twigs or stems. These egg cases can be collected, refrigerated through the winter, then set out in the garden in the spring. Three egg cases, whether collected locally or purchased through the mail or from your garden center, are usually enough to patrol about 5,000 square feet of garden. You can draw native mantises to your plot by planting cosmos, raspberries, or other brambles, or by allowing a stand of weeds to flourish. Those for sale are usually a large Chinese variety. Though these are said to be more active hunters, they are also less cold-hardy and will not overwinter in many areas.

Predatory Wasps (Family Vespidae)

This family includes various hornets and wasps, perhaps the most familiar of which are the yellow jackets and paper wasps. Aggressive predators, wasps search out a range of garden pests, from fat, plodding caterpillars to quick, darting spiders.

Like bees, wasps form highly ordered societies based around a solitary egg-laying queen. Hundreds to thousands of workers perform the myriad daily tasks, both within the colony and in the field as foragers. Drones fulfill but one function in life, then perish. Just like the beehive, the wasp colony functions as a sterling example of cooperative effort and teamwork. However, there are some remarkable differences.

As intricately organized as the wasp colony is, it is all the more amazing that each colony is but a fleeting civilization. Each year, every individual in the nest dies, with the sole exception of newly hatched queens. These new queens mate soon after emerging and leave the colony forever to search for a sheltered spot in which to hibernate through the winter. With the coming spring they will emerge to establish colonies of their own.