Chapter 12

Increasing Emotional Engagement through Storytelling

In This Chapter

Comprehending the superpowers of storytelling

Comprehending the superpowers of storytelling

Creating a purposeful sales story

Creating a purposeful sales story

Selecting the right story for your presentation

Selecting the right story for your presentation

Adding drama for emotional engagement and recall

Adding drama for emotional engagement and recall

Delivering your story with impact and confidence

Delivering your story with impact and confidence

You build a logical case for why your prospect should buy your product or service, but logic alone won’t move your prospect to take action. You need to engage your prospect emotionally, and storytelling is one of the most effective tools available to do that. Telling a story can gain emotional buy-in in a way that presenting countless facts and data simply can’t. Stories have many other super powers as well; they can gain attention, soften a hardened stance, overcome objections, and differentiate you and your product or service in a memorable way.

A smartly crafted, well-delivered story is a powerful vehicle for making a persuasive case. On the other hand, a long, irrelevant, or poorly told story can cost you attention, credibility, and undo any goodwill that you’ve managed to establish. More salespeople are starting to embrace the idea of using stories in their presentations; however, not a lot of them are doing it well because they’re missing one or more of the elements critical to an engaging, purposeful sales story.

In this chapter I examine the science behind why stories work, when and how to use them in your presentation, and what the ingredients are that go into creating a persuasive story. I introduce different types of stories you can use in your presentation and the elements of drama for maximum effect. I also discuss specific tools for crafting an effective story with examples and tips on when and where to use them in your presentation. Even if you don’t consider yourself a natural storyteller, by the end of this chapter you can discover the secrets to delivering a persuasive sales story with confidence.

Understanding Why Stories Work

There’s so much buzz about storytelling in business lately that you may think it was the latest app. In fact, long before the written word, stories were used as a vehicle to pass down information (don’t feed the dinosaurs), interpret events (what did that meteor mean?), instill values (Noah and the ark), and make sense of the world (the stars are the gods frozen in the sky), and of course, entertain.

Stories work for many reasons. Not only are stories a traditional form of communication, but in the following sections you also see how stories actually impact your prospect’s brain. You see how stories can help you do more showing and less telling, as well as create associations that increase understanding and recall of your message.

Impacting the brain with stories

Science has been studying the effect that stories have on people. Overwhelming evidence shows that they can do more in your presentation than just break up bullet points. Stories stimulate different parts of the brain and form a powerful connection between storyteller and listener:

-

Engaging the brain: Brain scans reveal that stories activate certain parts of the brain that don’t get activated by just delivering data or information. Most information goes into the language-processing area of the brain, and it processes language, that’s all. Stories activate the language-processing area as well, but they go a step further and stimulate other areas of the brain, which is why the experience of hearing a story is so much more vivid and memorable than just hearing a bunch of facts.

For example, a story that talks about how something feels stimulates your sensory cortex. A story that talks about how something moves triggers your motor cortex. Most sales presentations focus almost exclusively on the language-processing area of the brain, leaving the rest of the brain disengaged. By using a story, you capture greater mindshare and make a bigger impact on your prospect.

For example, a story that talks about how something feels stimulates your sensory cortex. A story that talks about how something moves triggers your motor cortex. Most sales presentations focus almost exclusively on the language-processing area of the brain, leaving the rest of the brain disengaged. By using a story, you capture greater mindshare and make a bigger impact on your prospect.

- Synching storyteller and listener: Recent research also indicates that during the telling of a story the brains of both the storyteller and the listener can actually synchronize. What it really means is that the part of your brain that is activated when you tell a story will likely be activated in your listener’s brain. A nice way to be more simpatico!

Showing with stories

Just like you, prospects are told things all day long: “We’re the best … . You should do this… . Here’s how this works …” Stories allow you to show your message, solution, or results in action which is much more effective than barraging them with a list of facts.

For example, telling your prospect about all of the amazing things your product can do may create a healthy amount of skepticism. Telling a story about a customer’s positive experience with your product is much more likely to make your prospect a believer or at least intrigue them.

Talking in stories

Storytelling is a natural way for people to communicate. If you really stopped to look at the content of the conversations you’re having with friends, relatives, and co-workers throughout the day, you may be surprised to find that much of it is in the form of stories. In fact, a recent study found that personal stories and gossip account for about 65 percent of people’s conversations. To not include storytelling in your presentation is almost, well, unnatural.

Associating with stories

Through a story you can help your prospect quickly understand and remember your message by associating it with something familiar. Because the human brain is very receptive to stories, people try and understand them. When you hear a story, your brain searches for a similar experience to relate it to. Finding that relationship helps you associate a new story with something familiar; in other words, you find a spot for this new information in your brain. This is especially helpful when you have a product or service that is new.

Leveraging Storytelling Super Powers in Your Presentation

Like a great movie, a great sales story can change the minds and hearts of audiences, differentiate you and your solution, and inspire action. But that’s not all. The following sections explain some of the other super powers that make it a must to include in your presentation.

Engaging emotion

Logic alone is never enough. Engaging your audience emotionally is critical for a persuasive presentation; storytelling is one of the most effective means of doing that. Stories can bring emotion into your presentation by putting a face and a name on a subject or explaining what those numbers mean and why that meaning is important.

Notice in political campaigns how often the candidates use stories of ordinary people to illustrate and drive home their points. (Bob, the auto worker from Detroit who had to take a second job in order to feed his family or Carol, the retired widow from New Hampshire, who had to go back to work in order to make ends meet …) They don’t present only the facts and the statistics because smart pollsters know that facts and figures are cold and unemotional abstracts. People care more about individuals than they do about abstractions. Stories can draw in prospects and get them emotionally involved in a way that just hammering them with numbers won’t.

Creating memories

Because stories can create emotion and emotion plays a critical role in your ability to remember, they’re vital in presentations that have a lengthy buying cycle or involve multiple decision makers. Many salespeople of more complex solutions don’t walk out of a presentation with a signed contract.

Decision makers may not get together for days or weeks to discuss your proposal. In the meantime, they’re likely to see other vendors and be presented with other options and priorities to handle. Using a story to frame a key point in your message is an effective way to make information stick in your prospect’s mind after you walk out the door.

Influencing opinion

An old Navajo expression says, “Those who tell the stories rule the people.” The real secret to the power of stories is that they can influence and change minds by allowing the prospect to draw her own conclusion. Butting heads and telling a prospect what she should believe leads to debate, judgment, or criticism — if not verbally, then certainly mentally. The right story can get a prospect off of a sticking point or shift her perspective by allowing her to weigh the story and form her own opinion.

Disarming an audience

One of the most powerful and proven ways to increase attention and recall is to do something unexpected. Using stories effectively and creatively in your sales presentation — beyond the standard business case or happy customer story — is still relatively uncommon. Take advantage of that fact to differentiate yourself and gain attention by having a few good stories up your sleeve.

Defining Purposeful Storytelling

Storytelling itself is the art of conveying an event, a thought, or an idea to another person by using language, images, or physicality. Much like in any conversation, you have different reasons for telling a story. Stories can be used to entertain, educate, inspire, or warn, but to be effective they must have a purpose. And like any element in a sales presentation, the purpose of a story is to move the sale forward, which means it must be related to why you’re there. Stories that lead nowhere and that are used to grab attention and nothing else can do more harm than good with busy decision makers.

Although telling a story just because it’s interesting or funny is fine for everyday conversations, a sales presentation is no everyday conversation. It’s a purpose-oriented, heightened conversation. Many stories fail in presentations because they don’t incorporate either one or both of these qualities.

The next sections show you how to create a purposeful story that rises above the everyday to engage your prospect. You also recognize when to use stories in your presentation and discover three key questions that can ensure your story is on the right track.

Heightening your story

Whatever story you choose to tell, keep in mind that it must be a heightened event. Stories about an everyday event — shopping for groceries, taking in your dry cleaning — where nothing really unusual happens are going to leave your audience yawning. To rise to a heightened state, something extraordinary must take place. By extraordinary, I don’t mean aliens landing, but rather, something out of the ordinary that gives your story a twist and creates conflict. For example, “I was shopping last minute for groceries for an important dinner party, and they were out of the one thing I knew how to make — salmon.” A heightened story includes the elements of drama, which I discuss more in the later section, “Incorporating the Elements of Drama in Your Story.”

Giving purpose to your story

Whatever story you tell, it should entertain and inform; however, in a presentation, entertainment can’t be its primary purpose. An effective sales story needs to be relevant or tie back to the reason that you’re there or the topic that you’re discussing; otherwise your prospect may well feel like you’re wasting her valuable time.

For example, consider how this story told at the opening of a presentation leads into a subject that’s relevant to the prospect.

“How many people have kids in college? Probably no surprise to you that tuition has doubled in the last decade. Cable? Tripled. Cost to service loans? Quadrupled. Few things have increased as dramatically in cost and from what you told us, it’s keeping you from focusing on your core competencies and limiting your ability to grow. We’re here today because our core competency — providing loan services — can complement what you do and allow you to focus on doing what you do best, providing excellent services to your clients. Let’s get started.”

This example illustrates how you can heighten and weave a story into your presentation in a purposeful way. Certainly the opening is a great place to use a story but I explore some other areas where a story may be just what’s called for in the next section.

Recognizing when to use stories

Stories can be a powerful tool, but like any tool, you need to know when and how to use them to be effective. Before you start putting a story together, first consider why you’re using it.

Here are some conditions where storytelling can be one of your go-to tools:

-

Gaining attention: Using a story to open your presentation is a great way to pull your prospect’s focus away from her phone, laptop, or thoughts and onto you and your message. But because attention isn’t a constant, at other times you also need to regain your prospect’s attention within your presentation. Using a story to frame a new topic or agenda item or highlight a feature or benefit is good way to wake up your prospect’s brain at key moments. See Chapter 5 for ways to use a story as an opening hook.

Your prospect’s attention naturally starts to wane after spending 10 minutes on any particular subject. A story is a great option to consider for those times when you need to reengage your prospect.

Your prospect’s attention naturally starts to wane after spending 10 minutes on any particular subject. A story is a great option to consider for those times when you need to reengage your prospect.

-

Changing a misconception or strongly held belief: Often you may find yourself faced with a prospect who has a well-established — and conflicting — opinion on a subject. For example, she has been using your competitor’s product for years and believes — incorrectly — that it’s superior to yours. To approach this type of resistance head-on is a losing strategy. No one likes to be told she’s wrong or misinformed. Rarely will you hear, “Thank you for correcting me.”

Your prospect is much more likely to get defensive and draw a bigger line in the sand — either through arguing back verbally or in her mind. With the right story you can soften a hardened position and open a prospect’s mind to a different perspective. By telling a story that presents an alternative outlook in a nonconfrontational manner, you allow your prospect to reevaluate and re-form her opinion without feeling like she is having her arm twisted.

Your prospect is much more likely to get defensive and draw a bigger line in the sand — either through arguing back verbally or in her mind. With the right story you can soften a hardened position and open a prospect’s mind to a different perspective. By telling a story that presents an alternative outlook in a nonconfrontational manner, you allow your prospect to reevaluate and re-form her opinion without feeling like she is having her arm twisted.

-

Simplifying complex ideas: People typically don’t want to buy something that sounds complicated or difficult to understand or use. The problem is that many products and services today have complex features or processes, which can make your product sound complicated. Using a story in this situation — particularly a metaphor or analogy — is an effective way to make what your product or service does quickly understandable to your prospect. Here’s an example:

Assume that you’re selling a system that allows your prospect to operate many of her business processes remotely. You could explain how the system collects, sorts, prioritizes, and transfers all the data. Or you could compare what your product does to the instrument panel on an airplane that allows the plane to safely go from point A to point B without manual input. With the second option, your prospect now has something familiar to associate your product with. Much like a good infographic, stories, especially metaphors and analogies (like the previous airplane example) — can give your prospect a quick mental picture of some pretty complicated ideas.

- Addressing an objection: Presentations aren’t always a smooth ride. You want to anticipate objections that may arise as part of your preparation efforts and have a strategy for addressing them. A story is one way to effectively diffuse an objection. Whether it’s a service or feature you don’t provide or a price or value issue, a well-crafted story specific to that objection is a handy tool to have. For more tips on handling objections, see Chapter 15.

- Reinforcing a message: You want to shine a light on some points within your presentation — a competitive advantage, a benefit, a value proposition — so that your prospect doesn’t miss them. Building a story around any key message or point is a powerful way to grab attention and improve recall of your message.

- Inspiring action: Your presentation goes well, everyone is in agreement and then … nothing happens. Time passes, other priorities pop up, and the deal gets stalled. Stories are a great way to create urgency for your prospect to take action — either by highlighting the pain of postponement and/or the benefits of taking quick action.

Planning a purposeful story

The tendency when using a story is to start with the story and then retrofit it into your presentation. Sometimes that strategy works, but often it feels forced or misses on some level. Before you jump in and come up with stories for your presentation; take a few minutes to answer the following three questions. They help to ensure that you’re using the right story at the right time.

- Why are you telling a story? As the previous section explains, a purposeful story must satisfy some need beyond to entertain or inform. Define what your purpose is. Is it to overcome a misconception? Illustrate how a feature works? Shift perspective or create urgency? Starting with your purpose gets you headed in the right direction as you start to consider story options.

- What’s the point or lesson? The lesson in your story is the outcome you want your prospect to connect to your message. For example, if I’m telling a story because my prospect is afraid of change, the lesson in my story would be that change brings good things or that not making a change can be riskier than change itself.

- How do I want my prospect to feel? Stories are about triggering emotions so consider what emotion you want to convey. Is it joy, relief, fear, pride? Defining how you want your prospect to feel at the end of your story influences the tone, the nature, and the type of story that you will tell.

Determining What Type of Story to Tell

Deciding on what kind of story to use is also important. Following are several types of stories that can be effective in a sales presentation. Reading the descriptions can help you decide which type of story is right for your specific situation.

Highlighting happy customers: Business case

The most common type of story used in a presentation, a business case example or a happy customer story as they’re often called, showcases an existing customer’s results from using your product or service. Pointing out a happy customer can be especially helpful when you need to establish credibility, as in the case of new companies or products, or existing companies expanding into new industries or markets.

Select a customer that has some relevance or similarity to your prospect. For example, you can use a customer in the same industry or even a different industry experiencing similar challenges as your prospect. Either way, you want to point out the pain of where your customer was, how you helped her, and where she is today. Because this type of story is so common in sales presentations, it doesn’t have the attention-grabbing power of other types of stories that I discuss in the following sections, so you need to work a little harder to make it interesting.

Select a customer that has some relevance or similarity to your prospect. For example, you can use a customer in the same industry or even a different industry experiencing similar challenges as your prospect. Either way, you want to point out the pain of where your customer was, how you helped her, and where she is today. Because this type of story is so common in sales presentations, it doesn’t have the attention-grabbing power of other types of stories that I discuss in the following sections, so you need to work a little harder to make it interesting.

Here are some tips for using business case stories successfully:

- Pull out relevant quotes. An interesting quote from your customer along with a picture can give a business story some needed personality.

- Use metrics. Metrics are measurable results that companies use to judge performance, like an increase in sales, reduction in turnover, improved ROI. Using a case study allows you to introduce these figures with a little color and context so don’t be shy about showing off those results. Give those figures a memorable boost by having them on a slide or writing them on a whiteboard or flipchart. Figure 12-1 shows an example.

- Add a personal touch. Because a business story typically has less of an emotional aspect to it, consider how you can personalize it in some way to make it real for your prospect. Did you work with the customer? Are there any quick, interesting details or anecdotes you can add to make this story come to life?

- Include dramatic elements. Because these stories are similar in content to the rest of your presentation, make them stand out by including dramatic elements like conflict and raising the stakes. You can see how to do it in the upcoming “Incorporating the Elements of Drama in Your Story” section.

Sharing about a day in the life

This type of story is an effective way to explain the application of a particular feature or capability of your product or service. In a day-in-the-life story you put yourself into the role of a person using your product who needs to accomplish a specific task or solve a problem. By using this type of scenario your prospect is able to more directly see and understand how and when she would use your product in her own job. For example:

“Let’s say I’m Jean a new HR person, and I’m told we need to hire a new engineer. I would first go into the system and find out what the salary range is for that position. Even though I’m unfamiliar with the system, I can easily find what I need by looking at the options on my dashboard. After I get that information, I would look for the job description … ”

Showing with a metaphor or analogy

Metaphors and analogies are popular literal devices used to compare one or more things to something else in an attempt to explain or entertain. People use metaphors all the time — the 800-pound gorilla, the elephant in the room, that’s a slippery slope. They’re like shorthand for communication because they quickly create a visual picture in your listener’s mind. Now you may no longer create a visual picture when someone says the elephant in the room because you’ve heard it so many times, but fresh, new metaphors and analogies can do a good job of communicating something quickly that you want the prospect to visualize. Here’s an example of an analogy:

“How many of you have a smartphone? But think back to before you had a smartphone. If you wanted to make a call, you needed a phone. If you wanted to send an email, you needed a computer. If you wanted to play music or watch a DVD, you needed a device for that, too. When the iPhone first came out, it was ground breaking for many reasons, but primarily because a single device replaced the need for a lot of those additional products. It was faster, easier, and more efficient. This reminded me of your organization because currently you’re using multiple systems to accomplish your job. What I’m going to show you today is how you can create a seamless end-to-end customer experience and achieve that goal more efficiently by using one system.”

A complex idea quickly conveyed in an easy to understand package. That’s the power of metaphors.

Here are some good rules to follow when using a metaphor in your presentation:

- Don’t overuse them. A metaphor about a ship, a volcano, and then a football game will have your prospect busy trying to keep the metaphors straight — and potentially miss your point entirely.

- Be creative. Avoid overused, such as “She was pale as a ghost,” or mixed metaphors, such as “Run it up the flagpole and see if it sticks.”

Finding just the right metaphor is often the trick. Here are some tips for designing your own metaphor:

Finding just the right metaphor is often the trick. Here are some tips for designing your own metaphor:

- Identify the subject that you’re trying to describe. Know whether it’s a feature, a benefit, or a concept — for example, 24/7 service and parts.

- List the characteristics of that subject you have identified. Write down all of the words or phrases you can think to describe your subject, including what it does, how it makes you feel, and what senses does it involve — for example, easy and fast access or worry-free buying.

- Brainstorm ideas of things that also share these same characteristics. Looking at your list, write down all of the different types of things that share those same qualities — for example, gas stations, convenience stores, concierge service, and warehouse stores.

- Write a sentence that compares your topic to the ideas you came up with. Create a comparative sentence connecting the two topics with the word like or as — for example, “Our service center is like having a private concierge for your business 24 hours a day.”

- Run it up the flagpole. Tell your metaphor without explanation to several people to find out if it makes immediate sense. If you have to explain it, it probably isn’t a good metaphor.

Revealing something personal

When done well, telling a personal story — something you’ve experienced, witnessed, or learned — is one of the most powerful elements you can add to your presentation. Personal stories contribute to the success and growth of everything from 12-step groups to religious organizations to political candidates. Telling a story from your perspective or experience allows your prospect to see the person behind the salesperson and helps forge a stronger connection as she steps into your shoes. Here’s an example of a personal story used at the opening of a presentation:

“I recently decided to remodel my bathroom. Because I consider myself a fairly handy person, I decided to save some money by doing it myself. After two weeks and $1,000 to get the right design and find all the materials, I was ready to start. Unfortunately, I realized that I needed some special tools. So back to the hardware store to spend another $200. When I finally started, I accidently cut a pipe and things got worse from there. I didn’t order enough tile, and the fixtures didn’t fit. After the bathroom had been off limits for a month, my wife had had it. What began as a fun little side project quickly turned into a much more costly and time-consuming job because frankly, it wasn’t my specialty. I finally hired a contractor, and he finished it perfectly in two days. The reason I tell you this is I know you’re considering using internal resources to do this project. Like me, I think you’ll find that it’s much less risky in terms of money and time to work with specialists.”

Many salespeople worry that a personal story is inappropriate for a business audience. Although a personal story may indeed be considered out of place in certain cultures, don’t be too quick to assume your audience fits into this small category. Your audience is made up of people — the same people who watch movies, read books, and tell stories to their children. Just because they’re at the office doesn’t mean they don’t appreciate a good story. That being said, telling a personal story isn’t without risk. You must be very cognizant of several things:

Many salespeople worry that a personal story is inappropriate for a business audience. Although a personal story may indeed be considered out of place in certain cultures, don’t be too quick to assume your audience fits into this small category. Your audience is made up of people — the same people who watch movies, read books, and tell stories to their children. Just because they’re at the office doesn’t mean they don’t appreciate a good story. That being said, telling a personal story isn’t without risk. You must be very cognizant of several things:

- Don’t make yourself the hero. If anything, you want to share some lesson you learned or shortcoming you were able to overcome like the previous example.

- Make extra sure that it’s relevant. An irrelevant story will really have your prospect’s head shaking. Be on point and on time.

- Commit to it. To be successful delivering a personal story, you must go all in. If you don’t appear confident (notice I said “appear” — see Chapter 10 for tips on gaining confidence) or come across as uncomfortable or uncertain, your prospect may dismiss your story as untrue or trivial and question your credibility.

Going with an anecdote

Unlike a personal story, an anecdote is a story about someone — or something — else. It’s not the friend-of-a-friend story (that no one believes), but rather something that you have a connection with, whether it’s through interest, knowledge, or experience. Stories about famous people, companies, and events are common subjects for anecdotes. Here’s an example:

“There are many things we now take for granted that at one point were revolutionary. Take the high jump. You’re probably used to seeing athletes jump over on their backs. But it didn’t used to be that way. In fact, up until 1965, high jumpers cleared the bar by using a straddle jump, which meant the big, burlier athletes were better equipped for it. Dick Fosbury was a slender jumper and invented this backward J style to help him clear the bar easier and at a greater height. This style, called the Fosbury Flop, won Fosbury the gold in the 1968 Olympics. It was by looking beyond what had always been done that Fosbury forever changed that sport. In the same way, we’re going to ask you to look beyond what you’ve been doing and consider a new, faster, leaner approach to running your business … ”

When choosing an anecdote for your presentation, keep your eyes open for these potential issues:

When choosing an anecdote for your presentation, keep your eyes open for these potential issues:

- Stay away from heavily trafficked areas. You can bet your prospect has heard the story of Apple or Microsoft’s beginnings, Henry Ford’s invention of the assembly line, and Michael Jordan’s success. If you’re going to visit popular ground, look for a different take on the same old story.

- Avoid controversial subjects. Religion, politics, sex, global warming — any of these could offend someone with a strong opinion. If you’re unsure whether your story crosses the line, total abstinence is your best bet.

Incorporating the Elements of Drama in Your Story

Stories are a form of drama, yet most sales stories I see are uniformly devoid of this quality. In an effort to appear more real or professional, salespeople often cut out anything resembling drama in their stories, which results in some really professional boring stories. Drama is certainly nothing to shy away from, especially in a story, here’s why:

Drama is all about action. It incites emotion and attracts interest. As the movie industry can attest to, drama can keep people in their seats and hold their attention for as much as three hours at a time.

Now aren’t those qualities — the ability to incite emotion and attract and hold attention — qualities you want to have in your presentation? Drama is a powerful magnet. It helps you to identify with and care about the people in the story. Instead of leaving prospects flat with another lifeless and forgettable story, apply the following elements of drama and take your prospect on a dramatic journey that engages them, gets them invested in the outcome, and sticks with them long after your presentation is over.

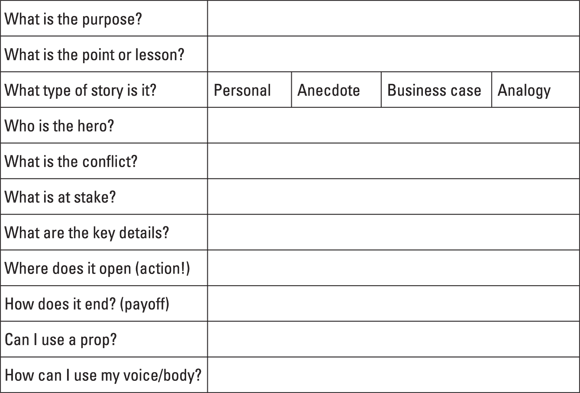

Following are some key elements of drama that can take your story from straight-to-video to box office hit. Use the story planning guide (see Figure 12-2) to make sure you don’t miss any of these critical elements.

Pick a hero

Every story needs a hero also known as a protagonist that an audience can identify with. The hero can be your solution or your prospect, but avoid making yourself or your company the hero as it comes across as arrogant.

Add conflict

Conflict is a vital part of a story and necessary to engage an audience. Thousands of movies and television shows rely on the fact that people are intrigued by conflict and tension and curious to know how things are going to turn out. If your story is just one happy romp from start to finish, you haven’t given your prospect much to hang on to. Stories require conflict and tension before ultimately coming to a resolution, so give your story the “So what?” test. If it doesn’t pass, you may need to escalate the dramatic tension with the next technique.

Raise the stakes

If the hero doesn’t find the bomb by midnight, the city will be destroyed. If the city is destroyed, the country will go to war. If the country goes to war the … You’ve seen this movie, right? The stakes keep getting higher until the audience members are on the edge of their seats! Contrast that with most stories where little is at stake. “I had to choose between a red car and a green car.” Ho hum.

You can’t expect your prospect to care about a story where there are no consequences. If you want to have your prospect on the edge of her seat instead of slumped over the table, raise the stakes in your story. If in your story the consequence of making a wrong decision is only a minor inconvenience, your prospect won’t care. However, if the consequence for a wrong decision were a $10,000 fine versus a $10,000 reward for the right decision, you’d have a better chance of piquing her interest. Stories should be a heightened reality; in other words, something important must be at stake. Make sure you know what is at stake in your story — money, pride, love, security?

You can’t expect your prospect to care about a story where there are no consequences. If you want to have your prospect on the edge of her seat instead of slumped over the table, raise the stakes in your story. If in your story the consequence of making a wrong decision is only a minor inconvenience, your prospect won’t care. However, if the consequence for a wrong decision were a $10,000 fine versus a $10,000 reward for the right decision, you’d have a better chance of piquing her interest. Stories should be a heightened reality; in other words, something important must be at stake. Make sure you know what is at stake in your story — money, pride, love, security?

Make the stakes as high as possible to increase engagement. No, it doesn’t have to be thousands of dollars or certain death, but if you do some digging, you can probably find more is at stake than you first realized. Here’s an example of a sales story with high stakes.

Make the stakes as high as possible to increase engagement. No, it doesn’t have to be thousands of dollars or certain death, but if you do some digging, you can probably find more is at stake than you first realized. Here’s an example of a sales story with high stakes.

“Recent clients of mine also needed to sell their house very quickly. They had twin girls going into their senior year in high school when the city announced they were redrawing boundaries, placing their current home just outside of their school district. After much searching, they found a house within the new boundaries and their offer was accepted, so they quickly put their house up for sale by themselves. After two price reductions their home finally went under contract, but a week before deadline the buyer backed out. My clients were either going to be stuck with paying two mortgage payments — which they couldn’t afford — or telling their girls that they’d be spending their senior year at a new school, leaving their friends of 12 years behind. Working together we were able to price their home right and market it effectively to qualified buyers and had an offer within three days. They were able to move into their new home in time for the girls to start their senior year with their friends.”

You can raise the stakes in the following ways:

- Brainstorm the consequences for your hero. Explore all the various consequences of making a wrong decision or no decision. Don’t limit yourself, and get creative.

- Raise the stakes. Continue to increase the dramatic tension by asking yourself after each consequence, “And then what would happen?”

- Include the stakes in your story. Highlight very clearly in your story what the highest stakes are for your hero so that your prospect stays engaged in the journey.

- Hold the final outcome until the end. Tension and curiosity is what keeps your prospect hooked so don’t give away the results until the end of your story.

Pick your details

Consider which details are necessary to move your story forward. Details are necessary to bring your story to life for your prospect, but providing too many details can make your story too long and quickly overwhelm your listener, creating tune-out. When first crafting a story, get all the elements of the plot down on paper. Read it aloud several times and continue to edit out those details that aren’t necessary or don’t add significant value or interest to your story.

Be specific

Clear and precise language is always more compelling than vague language to your listener. Select a few key elements in your story to describe in detail. Use sensory language when possible — for example, “it smelled like just after a rain” or “it looked like the surface of the moon.” Quantify when you can. For example, “99 percent” rather than “most” or “five” instead of “several” will be more meaningful and clear to your prospect.

Start with the action

Where you begin your story is a key factor in gaining and holding your audience’s attention. The reason most stories are too long is because the salesperson doesn’t recognize where the real story begins, and he errs on the side of including too much backstory before getting to the point. This is the kiss of death with today’s busy decision makers.

To start the story at the right point, think about where the action starts and provide just enough context to give your prospect some bearing. Here’s an example of a story starting with the action:

To start the story at the right point, think about where the action starts and provide just enough context to give your prospect some bearing. Here’s an example of a story starting with the action:

“In 1986 Jack Nicklaus was a long shot to win The Masters. He hadn’t won a title in 10 years, and there were lots of new, younger players on the tour. But he surprised the odds makers by winning his sixth Masters that year. It was his crowning achievement. Why did he win? Because he knew the course better than anybody. He knew what it took to win better than anybody. He had experience. And experience plus professionalism is always the best bet. In the same way, we recognize there are new players in the industry, and it makes sense for you to evaluate them. But in the end, we believe that you’ll realize that experience is the winning bet when it comes to taking your business where you want it to go.”

Now I could have started that story talking about Jack Nicklaus’s esteemed career, his rivalry with Arnold Palmer, or his successful golf course design business — all of which would take up valuable time and keep me from getting to where the story really starts — winning the 1986 Masters — and the real point of the story — experience is a winning bet.

Like well-written TV shows, assume your audience is smart and start where the action is. Certainly use enough detail to get your prospect oriented, but start with that attention-grabbing action scene and you’ll have your prospect hooked.

End with a payoff

Many stories fail because the ending is telegraphed way in advance. If your prospect sees it coming a mile away, there is no reason to stay tuned. Give your prospect clues, build your story to its climax, and when you’ve made the stakes as high as possible, reveal the outcome. Doing so gives your prospect a sense of completeness. The ending is the payoff, and the more tension you create beforehand, the greater the payoff at the end for your prospect.

Sharing Your Story with Skill and Confidence

A story is only as good as the storyteller. When it’s done well, storytelling looks incredible easy, but make no mistake, it requires planning, practice, and keen attention to timing and purpose to get it right. Even if you don’t consider yourself a natural storyteller, you can improve your storytelling skills dramatically by mastering a few of the following techniques from great storytellers for bringing a story to life:

- Just start. Don’t put your audience on notice that you are going to tell them a story. For example, “I’d like to share a story with you …” That sentence alone gets their defenses up: (“I don’t have time for a story! I want to hear how you’re going to help me.”) If your story is interesting, succinct, and relevant to your audience, they won’t have time to think these negative thoughts, so just begin.

-

Keep it short. In a world of increasing demands and expedited communication, your story needs to be short and to the point — think two to three minutes max. If you’ve followed the previous suggestions in this chapter about fleshing out a few key details and starting with the action, your story should be fairly concise. If it’s not, consider whether you’re trying to get too much across and take the time to edit down to the essence of what you’re trying to say.

Aim for keeping your story fewer than two minutes to avoid tune-out or impatience.

Aim for keeping your story fewer than two minutes to avoid tune-out or impatience.

-

Be descriptive. Think in terms of word pictures. In the previous section, “Impacting the brain with stories,” I discuss how your brain interprets stories that use sensory words, which can help your listener experience the story in a more three-dimensional way. Be careful not to go adjective crazy. Pick and choose only those descriptions that help color or advance your story.

By using sensory language you activate those areas in your listener’s brain. More brain activity means a more engaged audience.

By using sensory language you activate those areas in your listener’s brain. More brain activity means a more engaged audience.

- Incorporate your voice and body. A story is an opportunity to use more of your personality and express it through your voice and movement. Consider how you can vary the tone, volume, or pace of your voice as you tell your story. Incorporate dramatic pauses. Use gestures to describe things for your audience. For more tips on using your voice and body, see Chapter 11.

-

Use your stage. Don’t hide behind your laptop when telling a story. Imagine you’re telling a story to a friend rather than a speaker at the pulpit delivering an address. Connect to your prospect as you tell your story by using your stage to move toward her or position imaginary objects in your story on the stage with you and refer to them. See more on how to effectively use your stage in Chapter 11.

If you’re placing imaginary objects on the stage with you, be consistent and clear with your locations when you refer to them so that you don’t confuse your audience.

If you’re placing imaginary objects on the stage with you, be consistent and clear with your locations when you refer to them so that you don’t confuse your audience.

- Consider props. Think about how you can bring your story to life for your prospect. Perhaps there’s a picture you can show or an object, like a book, tool, or piece of clothing you can reveal. Even a small effort in this area goes a long way to making an impact on your audience. Chapter 14 looks into using props.

- Own your story. A half-hearted attempt to tell a story will fail. Be fully committed to sharing this story with your prospect. If it doesn’t come out exactly how you anticipated, keep going as if that’s exactly how you planned it.

- Rehearse well. Telling a story with impact takes a lot of practice, so don’t wait until the night before to start rehearsing your story. Practice saying your story aloud several times a day for at least a week before your presentation to make sure you have it down. If you find new ideas while you’re rehearsing, that’s great. Jot them down and incorporate them into your story, but beware of the length because you may have to eliminate something else. Having a good story ready to go gives you greater confidence and frees you up to really focus on your prospect.

Comprehending the superpowers of storytelling

Comprehending the superpowers of storytelling Creating a purposeful sales story

Creating a purposeful sales story Selecting the right story for your presentation

Selecting the right story for your presentation Adding drama for emotional engagement and recall

Adding drama for emotional engagement and recall Delivering your story with impact and confidence

Delivering your story with impact and confidence For example, a story that talks about how something feels stimulates your sensory cortex. A story that talks about how something moves triggers your motor cortex. Most sales presentations focus almost exclusively on the language-processing area of the brain, leaving the rest of the brain disengaged. By using a story, you capture greater mindshare and make a bigger impact on your prospect.

For example, a story that talks about how something feels stimulates your sensory cortex. A story that talks about how something moves triggers your motor cortex. Most sales presentations focus almost exclusively on the language-processing area of the brain, leaving the rest of the brain disengaged. By using a story, you capture greater mindshare and make a bigger impact on your prospect. Select a customer that has some relevance or similarity to your prospect. For example, you can use a customer in the same industry or even a different industry experiencing similar challenges as your prospect. Either way, you want to point out the pain of where your customer was, how you helped her, and where she is today. Because this type of story is so common in sales presentations, it doesn’t have the attention-grabbing power of other types of stories that I discuss in the following sections, so you need to work a little harder to make it interesting.

Select a customer that has some relevance or similarity to your prospect. For example, you can use a customer in the same industry or even a different industry experiencing similar challenges as your prospect. Either way, you want to point out the pain of where your customer was, how you helped her, and where she is today. Because this type of story is so common in sales presentations, it doesn’t have the attention-grabbing power of other types of stories that I discuss in the following sections, so you need to work a little harder to make it interesting.

When choosing an anecdote for your presentation, keep your eyes open for these potential issues:

When choosing an anecdote for your presentation, keep your eyes open for these potential issues: