A DICTIONARY

OF SOURCES

AA

Alfirin. To the Elves, the Alfirin flowers were like the great gold bell of Valinor in miniature.

AEGIR A Norse nature spirit, or jötunn, comparable to the Greco-Roman sea-god Pontus and Tolkien’s Ossë, the Maia of the Waves. Aegir was subservient to Njörd, the Norse god of the sea, just as Ossë is to Tolkien’s Ulmo, the Lord of Waters. Like Ossë and Pontus, Aegir was known for his wildly shifting moods and his tempestuous nature, and was much feared by mariners.

AEGLOS (“SNOW POINT” OR “ICICLE”) The Elf-forged spear of Gil-galad, the High King of the Noldor of Middle-earth in the Second Age. Aeglos’s inspiration was likely Gungnir—meaning “swaying one”—the magical Dwarf-forged spear of Odin, the Norse god. Like Aeglos, Gungnir was a weapon before which “none could stand” and that would always strike its mark. Aeglos is broken when Gil-galad falls in his duel with Sauron at the close of the War of the Last Alliance. Gungnir was broken when Odin carried it into the final battle of Ragnarök.

AENEAS The mythical prince of the ancient city of Troy and Tolkien’s Prince Eärendil the Mariner have parallel lives, both being founders of nations. According to the Roman poet Virgil in his epic poem the Aeneid (completed 19 BC), the progenitor of the Romans was Aeneas, the son of the mortal Prince Anchises and the immortal goddess Venus. According to Tolkien, the progenitor of the Númenóreans is Prince Eärendil, the son of the mortal nobleman Tuor and Idril, the immortal Elven princess. Aeneas survived the destruction of the royal city of Troy and then sailed for many years lost in the paths of many enchanted isles, while Eärendil survived the destruction of the royal city of Gondolin and then sailed for many years lost in the paths of the Enchanted Isles. With the help of the goddess Venus, Aeneas traveled to Elysium, the Land of the Blessed, then returned to guide his people into a western sea and their promised land in Italy. Similarly, with the help of Elwing, the Elvish princess, Eärendil travels to Aman, the Blessed Realm, then returns to guide his people into the Western Sea and the promised land of Númenor.

In Italy, descendants of Aeneas, the brothers Romulus and Remus, founded Rome, a city and civilization that was destined to develop into an empire that would conquer and rule the world. In Middle-earth, descendants of Eärendil, the brothers Isildur and Anárion, founded Gondor, a city and civilization that was destined to create an empire that would likewise conquer and rule the world.

AESIR One of the two groups of Norse gods (the other being the Vanir) who united to form a single pantheon. In many respects, the Aesir are comparable to the Vanir, one of the two groups of “angelic powers” in Tolkien’s legendarium (the other being the Maiar). Although in terms of their hierarchical structure, Tolkien’s Valarian pantheon clearly shows the influence of the Greco-Roman gods of Olympus, in appearance and temperament the Valar and Maiar have far more in common with the gods of the Norsemen and other Germanic peoples. The home of the Aesir was Asgard, one of the Nine Worlds of the Norse cosmos, located at one end of Bifröst, the rainbow bridge, and on the highest branch of the Yggdrasil, the world tree. Tolkien’s Manwë, king of the Valar, is enthroned on Taniquetil, the highest mountain in Arda, while Odin, king of the Aesir, was enthroned in Hildskjalf, the highest hall in Asgard. Among the other Aesir gods were Thor, Frigg, Tyr, Loki, Baldur, Heimdall, Idunn, and Bragi. The Vanir gods, including Freya, Freyr, Njörd, and Nerthus, lived in the nearby world of Vanaheim, on another branch of Yggdrasil.

AGLAROND Meaning “Caves of Glory” in Sindarin (Grey Elvish), Aglarond is the name given to the spectacular caverns in the White Mountains, close to Helm’s Deep. Aglarond, as translated from the common tongue of Westron, is known as the “Glittering Caves.” There, in the wake of the War of the Ring, Gimli the Dwarf founds a new colony of Durin’s Folk. Tolkien acknowledged that the caves were inspired by the vast real-world caves of Cheddar Gorge in the Mendip Hills of Somerset, in southwestern England. One of the greatest “natural wonders” of Britain, this vast limestone gorge and cave complex is the site of some of the island’s earliest Paleolithic human remains. Aglarond and the Cheddar Gorge and Caves both appear to have been formed by underground rivers, and their vast galleries contain deep reflecting pools with remarkable stalactite and stalagmite formations. Tolkien was known to have visited Cheddar Gorge and its caves on at least two occasions: in 1916, while on his honeymoon, and again in 1940.

See also: GIMLI

AINUR The “Holy Ones” are the angelic powers serving Tolkien’s supreme being, Eru, “The One.” The Ainur are comparable to the angels in the service of the one God, the biblical Jehovah or Yahweh, in the Judaeo-Christian tradition. In Tolkien’s cosmology, it is the Ainur as a celestial choir who, at the bidding of Eru, sing the world into existence. The contribution of the Judeo-Christian tradition to Tolkien’s imaginative writing is profound in its moral implications. However, in most respects, the ancient Judeo-Christian world is very unlike Tolkien’s.

As Tolkien informs us, the Ainur, many of whom subsequently enter the created world of Arda, are “beings of the same order of beauty, power, and majesty as the gods of higher mythology.” Indeed, those Ainur who enter Arda become known as the Valar and the Maiar, taking physical forms comparable to the gods of ancient Greek, Roman, and Germanic mythology. And although the inhabitants of Tolkien’s world do not quite worship these “gods,” the beliefs they hold surrounding these angelic powers are much closer to those of the ancient Greeks, Romans, and Germanic peoples than they are to the fierce monotheism of the ancient Israelites.

See also: ANGELS; MAIAR; “MUSIC OF THE AINUR”; VALAR

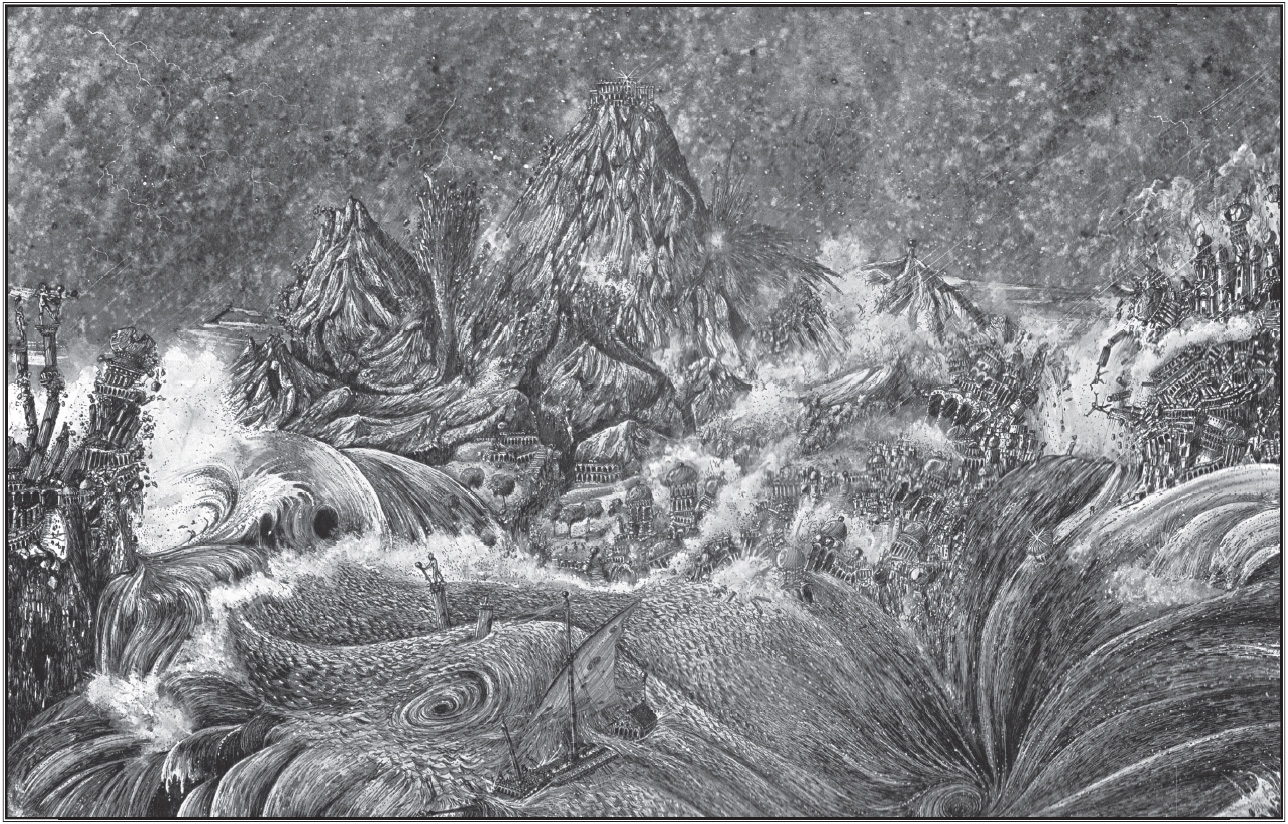

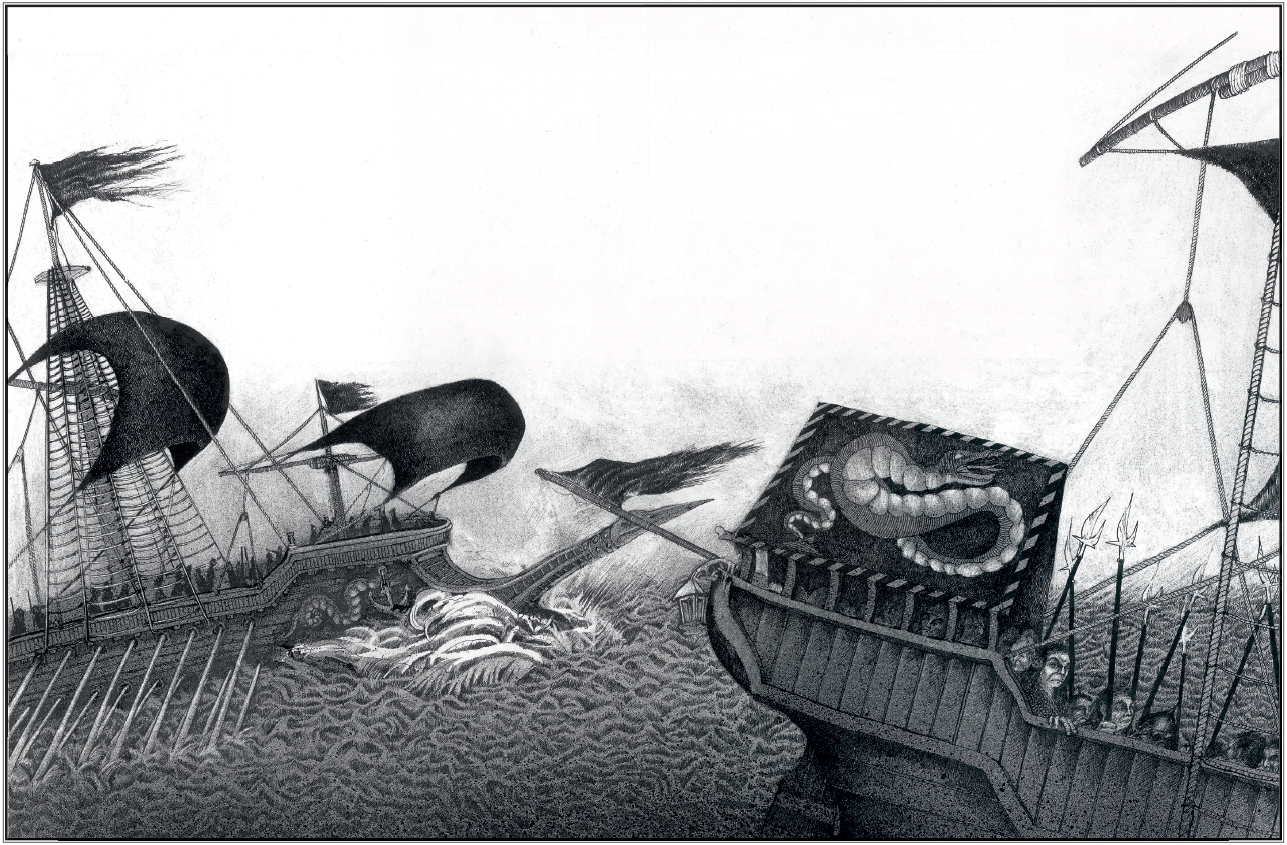

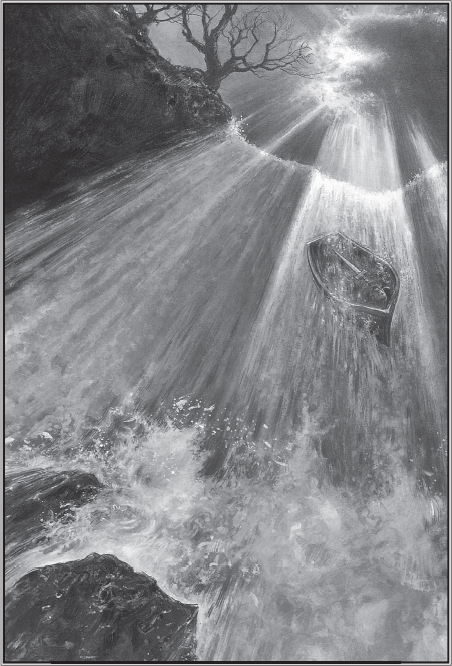

AKALLABÊTH “The Downfall of Númenor” is Tolkien’s reinvention of the ancient Greek Atlantis legend. Tolkien often mentioned that he had “an Atlantis complex,” which took the form of a “terrible recurrent dream of the Great Wave, towering up, and coming in ineluctably over the trees and green fields.” He appears to have believed that this was some kind of racial memory of the ancient catastrophe of the sinking of Atlantis, and stated on more than one occasion that he had inherited this dream from his parents and had passed it on to his son Michael. In the writing of Akallabêth, however, Tolkien found that he had managed to exorcise this disturbing dream. Evidently, the dream did not reoccur after he dramatized the event in his own tale of the catastrophe. The original legend of Atlantis comes from Plato’s dialogues, Timaeus and Critias (both c. 360 BC), which include the story of an island kingdom that some nine thousand years before had been home to the mightiest civilization the world had ever known. Atlantis was an island about the size of Spain in the western sea beyond the Pillars of Heracles. Its power extended over all the nations of Europe and the Mediterranean, but the overwhelming pride of these powerful people brought them into conflict with the immortals. Finally, a great cataclysm in the form of a volcanic eruption and a tidal wave resulted in Atlantis sinking beneath the sea. Tolkien used Plato’s legend as an outline for Akallabêth. However, Tolkien seems to have been incapable of doing what most authors would have done—writing a straightforward dramatic narrative based on the legend. Typically, he just couldn’t help adding little personal touches such as the compilation of three thousand years of detailed history, sociology, geography, linguistics, and genealogy.

See also: ATLANTIS

Akallabêth

ALCUIN OF YORK (c.735-804)

The Christian tutor and adviser to Charlemagne, King of the Franks and Holy Roman Emperor. His role is comparable to that of Gandalf as Aragorn’s mentor, counselor, and spiritual guide. Just as the Wizard Gandalf inspired Aragorn’s revival of the Reunited Kingdom of Arnor and Gondor, so the English churchman Alcuin was the driving force behind Charlemagne’s revival of the Roman Empire. There is a deeper, theological connection between the two figures, however. Alcuin dared to remind Charlemagne that an emperor’s authority was only borrowed from God, advising him: “Do not think of yourself as a lord of the world, but as a steward.” Alcuin’s words may remind us of those of Gandalf to Denethor the Ruling Steward of Gondor: “For I am also a steward. Did you not know?” Both Alcuin the churchman and Gandalf the Wizard had obligations far beyond the rise and fall of the petty kingdoms of mortal humans. Gandalf the Wizard is the embodied form of the immortal Maia Olórin and his allegiance is to the Guardians of Arda, whose authority is only borrowed from Eru Ilúvatar. Ultimately, Gandalf is steward to Eru the One, as Alcuin was steward to his Christian God.

See also: CHARLEMAGNE

ALFIRIN An often white, bell-like flower of Middle-earth known for blooming profusely about the tombs of Men. To the Men of Rohan it is Simbelmynë (“evermind”), while its Elvish name, Alfirin, means “immortal”—both names suggesting its association with commemoration of the dead. As a flower, Tolkien himself compared it to the anemone, which the ancient Greeks associated with mourning: when the goddess of love Aphrodite wept over the grave of her lover Adonis, her tears turned into anemones.

ALI BABA In the famous Middle Eastern folktale, Ali Baba is the unassuming hero who discovers that the secret to opening the stone door of the Forty Thieves’ treasure cave is uttering the words: “Open Sesame!” The “door in the mountain” theme is a common one in fairy tales and legends, found, for example, not only in “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves” but also in “Aladdin” and “The Pied Piper of Hamelin.” Tolkien, too, drew on the motif. Entry into the treasure cave of the Dwarves in The Hobbit is by way of a secret door in the Lonely Mountain of Erebor, and he repeats the motif in The Lord of the Rings. When the Fellowship of the Ring arrives at the West Door of Moria, the entrance is sealed shut, though, as Gandalf states: “these doors are probably governed by words.” In this case, the West Door of Moria is unlocked and opened by uttering the Elvish word mellon, meaning “friend.” For Tolkien, however, the motif—and Gandalf’s statement—had a deeper, creative meaning. Words were the keys to all of Tolkien’s kingdoms of Middle-earth: a world he explored and discovered through language, runes, gnomic script, and riddles. Words unlocked the doors of Tolkien’s imagination as a writer.

ALFHEIM One of the Nine Worlds of the Norse world and comparable to Tolkien’s land of Eldamar in the Undying Lands. As the name Alfheim implies, this was the “home of the elves,” or, more specifically, of the light elves. There was a second Norse elf-world called Swartalfheim, “home of the dark elves.” These divisions reappear in Tolkien’s division of his race of Elves: the Caliquendi, the Light-Elves who came, at least for a while, to the immortal lands of Eldamar (“Elvenhome”), and the Moriquendi, or Dark-Elves, who remained in the mortal lands of Middle-earth.

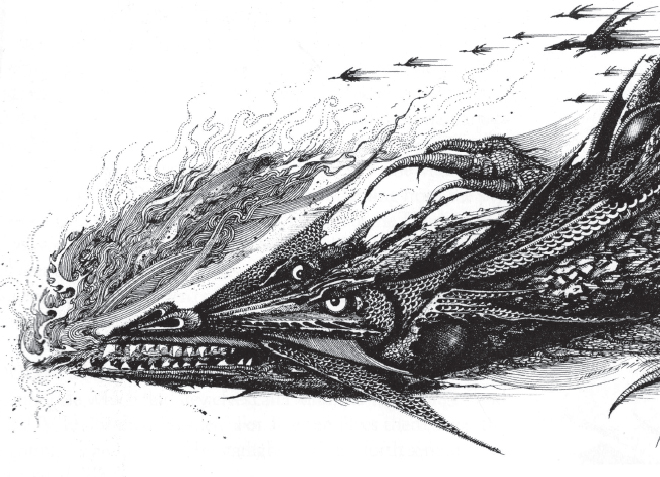

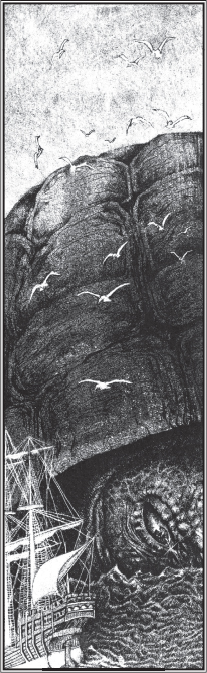

ANCALAGON THE BLACK The first and greatest of the vast legion of Winged Fire Drakes that Morgoth releases from the deep dungeons of Angband in the last battle of the War of Wrath at the end of the First Age. The attack of Ancalagon (meaning “rushing jaws”) in that last Great Battle has a precedent in the account of the great Norse battle of Ragnarök found in the Old Norse poem Völuspá (part of the Poetic Edda) where “the flying dragon, glowing serpent” known as Nidhogg (meaning “malice striker”) emerges from the underworld, Niflheim. Like Nidhogg, the ravening majesty that is Ancalagon unleashes a terrible withering fire down from the heavens. In the Prose Edda’s account of Ragnarök, we have another dragonlike monster, Jörmungandr, the World-Serpent, who rises up with the giants to do battle with the gods, and bring about the destruction of the Nine Worlds. In this version of Ragnarök, the god Thor appears in his flying chariot and, armed with the thunderbolt hammer Mjölnir, slays Jörmungandr. In Tolkien’s Great Battle, the hero Eärendil, appears in his flying ship Vingilótë and, armed with a Silmaril, slays Ancalagon.

ANDÚRIL The reforged ancestral sword of the kings of Arnor whose name means “flame of the west.” Originally known as Narsil (“red and white flame”), it is first forged by Telchar, the Dwarf-smith of Nogrod and wielded by King Elendil. The weapon largely has its inspiration in the thirteenth-century Icelandic poem Völsunga Saga, where the dynastic sword of the Völsung clan, known as Gram (“wrath”), is forged by the elves of Alfheim and first wielded by King Sigmund, until the blade was broken in his duel with Odin, the Lord of Battles. This is comparable to the fate of Narsil, which is wielded by Elendil until the blade is broken in his duel with Sauron, the Dark Lord.

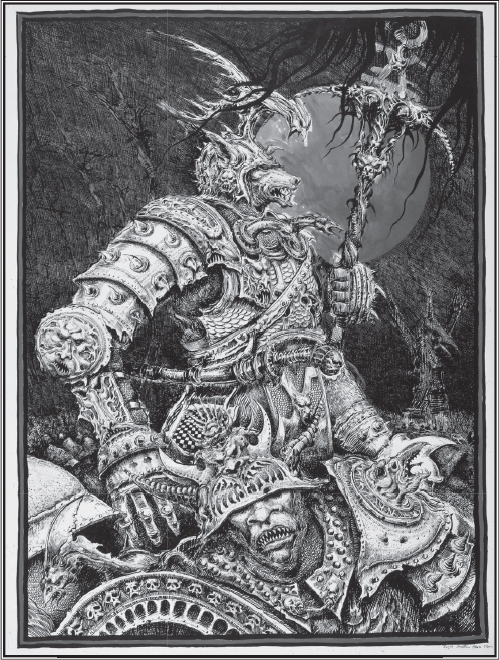

Ancalagon the Black

The shards of Narsil are reforged by the Elves of Rivendell for Aragorn, the rightful heir to the kings of Arnor, and renamed Andúril. Its unbreakable blade flickers with a living red flame in sunlight and a white flame in moonlight. Similarly, the Völsung sword Gram is reforged by Regin the Dwarf-smith for Sigurd, the rightful heir to the kings of the Völsungs. Its unbreakable blade is distinguished by the blue flames that play along its razor-sharp edge.

See also: TELCHAR

ANDVARI In Norse mythology, a dwarf who lives under a waterfall and possesses a magical ring called the Andvarinaut, or “Gift of Andvari.” In some respects, Andvari’s tale resembles that of Gollum. Both are solitary hoarders of magic rings but lose them through trickery: Andvari is tricked by the god Loki, and Gollum by the Hobbit Bilbo Baggins. Both lust after its return, and both curse ever after all those who take possession of the ring. In the Norse tradition, the ring was also known as “Andvari’s loom” because of its power “to weave gold” and was believed to be the ultimate source of the cursed gold of the Nibelung and Völsung treasure hoards. This ring is comparable in its powers to that of the Seven Dwarf Rings of Middle-earth: the ultimate source of the cursed gold of the Seven Dwarf treasure hoards. As Tolkien would also have been aware, these ancient ring legends were the source of the riddling story “Rumpelstiltskin,” where the ring is substituted with a spinning wheel that has the power “to spin gold”—a fairy-tale version of “Andvari’s loom.” In Richard Wagner’s opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen (first performed 1876), Andvari appears as the dwarf Alberich the Nibelung.

ANGBAND (“IRON PRISON”) A subterranean fortress and armory inhabited by Morgoth, the Dark Enemy, and his army of fallen Maiar spirits. In many respects, Angband is comparable to the subterranean fortress and armory of Tartarus or Hell in John Milton’s Paradise Lost (first edition, 1667), inhabited by the biblical Satan, the Prince of Darkness, and his army of fallen angels. A major difference, however, is that the pits of Angband are created by Morgoth and his allies because of their love of evil and hellish darkness, while Tartarus is created as a place of punishment for Satan and the other fallen angels. Both Angband and Tartarus serve as mighty fortresses and armories out of which lords of darkness launch their wars against the forces of light.

See also: STRONGHOLDS

ANGELS The mighty spirits who serve the god Jehovah/Yahweh in Judeo-Christian tradition provide some of the inspiration for the Ainur, or “Holy Ones,” in Tolkien’s cosmology. The Ainur are brought into being as thoughts from the mind of Eru Ilúvatar. Drawing on the ancient classical tradition of the Music of the Spheres (attributed to Pythagoras), Tolkien’s creation myth, told in Ainulindalë, has these angelic powers form a heavenly choir and sing the cosmos into existence. Thereafter, many of the angelic spirits choose to enter the newly created world of Arda in the form of the Valar and Maiar, supernatural beings of the same order and power as the gods of the Germanic and Greco-Roman pantheons.

See also: RELIGION: CHRISTIANITY

ANGMAR (“IRON HOME”) One of the domains of the Hill-men, lying on the northern borders of Eriador in the foothills of the Misty Mountains. By the year 1300 TA the area is ruled by the Lord of the Nazgûl, who subsequently becomes known as the fearful “Witch-king of Angmar.”

In the context of European history, the Hill-men of Angmar most resemble the Basques, the indigenous mountain people of the western Pyrenees bordering modern France and Spain. For centuries the Basques fought against Roman, French, and Spanish incursions into their lands, and constantly rebelled against those powers. The Basques were long resentful of the powerful Roman Empire and its later successor states, just as the Hill-men, too, resent the kings of Arnor. Consequently, the Hill-men were easily corrupted by the Witch-king and persuaded to enter into a disastrous war of attrition. After seven centuries, the Witch-king’s long war ended with the Battle of Fornost (1975 TA) and the mutual destruction of both Arnor and Angmar.

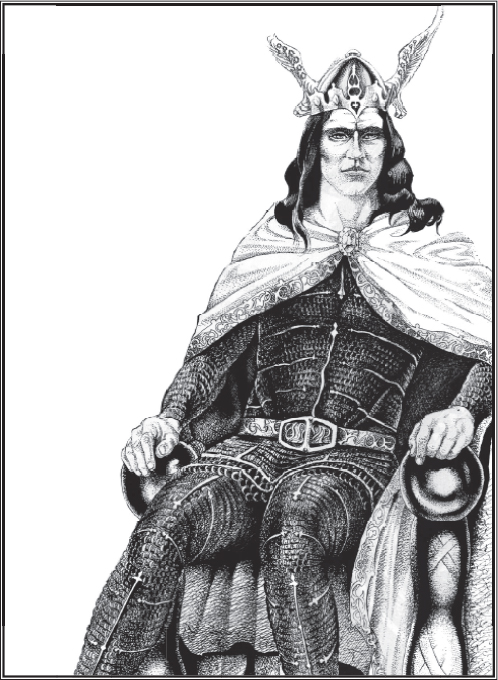

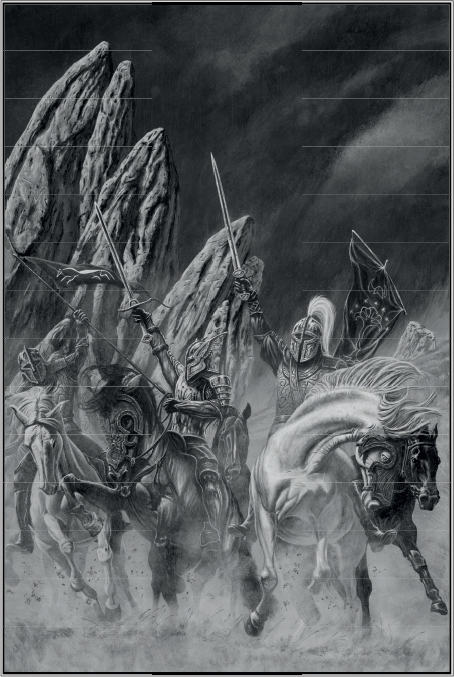

Aragorn II. The last Chieftain of the Dúnedain of the North after he was crowned King Elessar of the Reunited Kingdom of Gondor and Arnor after the War of the Ring.

ANNATAR

See: PROMETHEUS

ARAGORN Tolkien’s archetypal hero and future king of the Reunited Kingdom of Arnor and Gondor. English-language readers of The Lord of the Rings frequently register a connection between the legendary King Arthur and Aragorn. What is not often apparent, however, is that twelfth-to fourteenth-century Arthurian romances are often based on fifth-century AD Germanic–Gothic oral epics—epics that now only survive in the myths of their Norse and Icelandic descendants. Tolkien was far more interested in the early Germanic elements of his tales, which link Aragorn with Sigurd the Völsung, the archetypal hero of the Teutonic ring legend.

Although all three heroic warrior kings—Sigurd, Arthur, and Aragorn—are clearly similar, the context out of which each arises—in pagan saga, medieval romance, and modern fantasy—is very different. The creation of the essentially medieval King Arthur and his court of Camelot, with its Christian ethos, naturally resulted in some reshaping of many of the fiercer aspects of the early pagan tradition. Sigurd the Völsung is a wild warrior who would have been out of place at Arthur’s polite, courtly Round Table. Curiously, although Tolkien’s Aragorn is an essentially a pagan hero, he is often even more upright and ethically driven than the Christian King Arthur.

ARAWN A Celtic otherworld deity and the likely inspiration for Tolkien’s Oromë, the Huntsman of the Valar. Arawn provides an imaginative link between the fictional history of the Elves and the mythological world of the ancient Britons. The Welsh knew this god as Arawn the Huntsman, while Oromë (meaning “horn blower”) was known to the Sindar (Grey Elves) as Araw the Huntsman. The Welsh Arawn was an immortal huntsman who like Araw/Oromë rode like the wind with horse and hounds through the forests of the mortal world. In the First Branch of the Mabinogi, Arawn the Huntsman befriends the mortal Welsh king, Pwyll, who travels into the immortal Otherworld of Annwn. In the mortal lands of Middle-earth, Araw/Oromë the Huntsman befriends three Elven kings (Ingwë, Finwë, and Elwë), who travel to the immortal Undying Lands of Aman.

ARDA The High Elven (Quenya) name for Tolkien’s fictional world, encompassing the mortal lands of Middle-earth and the immortal Undying Lands of Aman. Arda, Tolkien insisted, is not another planet, but our world: the planet Earth. As the author himself explained: “The theatre of my tale is this earth, the one in which we now live, but the historical period is imaginary.” The connection is made clear in the name: Arda is connected to the Old High German Erda and Gothic airþa, both of which translate as “Earth.”

See also: MIDDLE-EARTH

ARIEN Maia maiden spirit of fire who each day carries the Sun aloft, illuminating Tolkien’s world of Arda. She is very much like the Norse goddess Sunna, who was the guardian and fiery personification of the Sun.

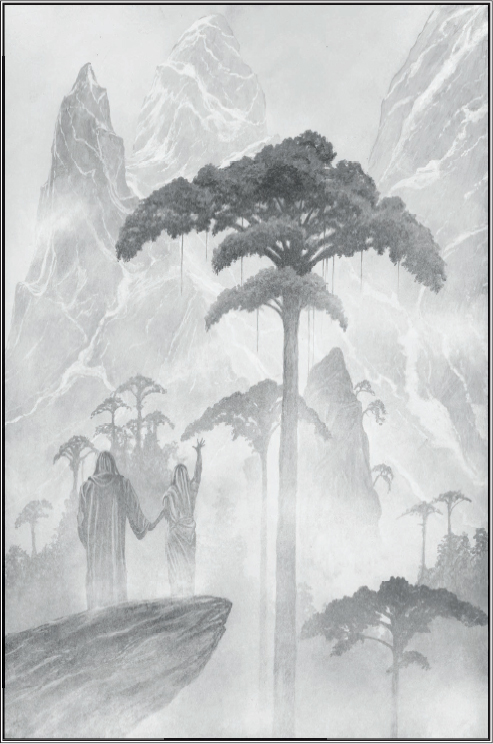

In the ages following the destruction of the Trees of Light in Arda, the angelic Arien rises into the air and carries aloft the crystal vessel that contains the last glowing fruit of the Golden Tree of the Valar into the firmament. Similarly, it was the Norse goddess Sunna who drove the chariot of the Sun across the sky each day to light the Nine Worlds. Sunna’s brother was Mani, the Norse god and personification of the moon, who in turn is comparable to Tolkien’s Maia moon spirit, Tilion of the Silver Bow. Both Tolkien’s and Norse mythology reverse the more commonly found gender of the deities of the Sun and Moon. The Greek and Roman deities of the Sun, for example, were respectively the male gods Helios and Sol while the Greek and Roman deities of the Moon were respectively the female goddesses Selene and Luna.

ARMAGEDDON The location of the prophesied great battle fought between the forces of good and evil at the “end of time” (and by extension the name of the cataclysm itself), as revealed in the Book of Revelation in the New Testament. Tolkien’s Great Battle in the War of Wrath at the end of the First Age owes some of its inspiration to the biblical Armageddon. However, instead of an ultimate duel between Tolkien’s Eärendil the Mariner and Ancalagon the Black Dragon, we have a duel between the Archangel Michael and the “Red Dragon,” as described in the Book of Revelation (12:7–10): “Then war broke out in heaven. Michael and his angels fought against the dragon, and the dragon and his angels fought back. But he was not strong enough, and they lost their place in heaven. The great dragon was hurled down—that ancient serpent called the devil, or Satan, who leads the whole world astray. He was hurled to the earth, and his angels with him.” Just as the Red Dragon’s downfall marks Satan’s defeat, so the Black Dragon’s downfall marks the defeat of Morgoth in Middle-earth. The Host of the West, like the Host of Heaven, prevails, and, as with Satan, no mercy or forgiveness is granted: Morgoth the Dark Enemy is cast forever after into the darkness of the Eternal Void.

AR-PHARAZÔN The twenty-fifth and last king of Númenor. His seduction and downfall through the deceit of Sauron the Ring Lord is comparable to the biblical legend of that other Ring Lord, King Solomon. In the tale of Solomon’s Ring (or Seal) found in Jewish tradition, we find a mighty demon, Asmodeus, who resembles Sauron at his most guileful. In the Hebrew story, Asmodeus—as the king of earthly demons—acts as a subtle agent of evil who corrupts the all-powerful but fatally proud King Solomon of Israel. In Sauron the Dark Lord, similarly, we see a subtle agent of evil who corrupts the all-powerful but fatally proud King Ar-Pharazôn of Númenor.

Just as Sauron surrenders to Ar-Pharazon and begs to be his trusted royal servant, so the demon Asmodeus, in his guise as a trusted royal servant, becomes Solomon’s evil tempter. Solomon is given visions of power and grandeur and begins sacrificing to the gods his various wives, going so far as to build a great temple to the goddess Ashtaroth on the slopes of Mount Moriah. As a consequence, he falls from the grace of Yahweh, the One God of the Israelites. This is comparable to Sauron’s temptation of Ar-Pharazôn through visions of conquest and immortality and to the building of a great temple to Morgoth on the slopes of Mount Meneltarma, where sacrifices were made to this evil god. Like Soloman, Ar-Pharazôn falls from the grace of Eru the One. Upon King Solomon’s death, it is prophesied, Solomon’s kingdom would be divided, his temple and books destroyed, and the demons of disease and war released again upon the world. The fate of Tolkien’s Númenor is even more disastrous: earthquakes and tidal waves destroy both nation and people as the island-continent sinks beneath the waters of the Western Sea.

ARTEMIS As well as goddess of the Moon, Artemis was the Greek goddess of the hunt and the protector of wild animals and wild places. Forest groves, meadows, and deer were sacred to this goddess, whom the Romans equated with the goddess Diana. Tolkien’s Nessa the Swift, the Vala sister of Oromë the Huntsman and the spouse of Tulkas the Strong, has some similarities with Artemis. Although Nessa is not a virgin huntress like Artemis, both are “swift as an arrow” with the ability to outrun the deer of the forest. Nessa cultivates all forms of animal and vegetable life in the Woods of Oromë in the Undying Lands. And, like Artemis, she also takes great delight in gatherings with other maids in its glades and meadows (both deities are closely associated with dancing). Another interesting comparison lies in the sibling kinship between Nessa and Oromë and Artemis and Apollo, although Tolkien does not elaborate on this.

ARTHUR The legendary British king is on many levels similar to Aragorn the Dúnedain, Tolkien’s most prominent hero in The Lord of the Rings. Aragorn is destined to become Elessar, the king of the Reunited Kingdom of Gondor and Arnor.

The comparison of Arthur and Aragorn demonstrates the power of archetypes, especially in dictating aspects of character in the heroes of legend and myth. If we look at their lives, we see certain identical patterns: Arthur and Aragorn are orphaned sons and rightful heirs to kings slain in battle; both are deprived of their inherited kingdoms and are in danger of assassination. Both are all apparently the last of their dynasty, their lineage ending if they were slain; and both are raised secretly in foster homes under the protection of a foreign noble who is a distant relative (Arthur is raised in the castle of Sir Ector and Aragorn in Rivendell in the house of Elrond). During their fostering—in childhood and as youths—each hero achieves feats of strength and skill that mark them for future greatness. Both fall in love with beautiful maidens, but must overcome several seemingly impossible obstacles before they can marry: Arthur to Guinevere and Aragorn to Arwen. And, ultimately, by overcoming these obstacles they win both love and their kingdoms.

See also: MORTE D’ARTHUR

ARWEN EVENSTAR The Elven princess also known as Arwen Undómiel, meaning “evening maid” or “nightingale.” Arwen has many links with the fairy-tale heroine Snow White, whose story was first written down by the Brothers Grimm in 1812. Both are raven-haired beauties with luminous white skin. Both have associations with supernaturally powerful queens who possess magic mirrors (although, unlike Snow White’s stepmother, Arwen’s grandmother Galadriel is a benign figure). And Arwen, like Snow White, has a “Prince Charming” lover: the future king of the Reunited Kingdom of Arnor and Gondor, Aragorn. Tolkien also pointedly links Arwen Evenstar to Varda Elentári, the Valarian “Queen of the Stars” who is also known by the epithet “Fanuilos,” meaning “Ever-White.”

ASGARD One of the Nine Worlds of the Norse cosmos, home to the all-powerful and immortal Aesir, ruled by Odin and Frigg, the king and queen of the gods. It has similarities with Tolkien’s Valinor, home to the Valar, ruled by Manwë and Varda. Asgard is divided into several regions, each of which has a great hall belonging to one of the gods. The greatest of the halls is Hildskjalf, which contains the high seat of Odin the Allfather. Valinor is similarly divided into several regions, each of which has a great hall belonging to one of the Valar. The greatest stands on Taniquetil, the highest mountain in Arda, where Manwë, Lord of the Winds, is enthroned.

ASMODEUS The powerful demon in the ancient Hebrew legend of Solomon’s Ring. As the king of earthly demons, Asmodeus’s role in the seduction of King Solomon is comparable to that of Sauron the Dark Lord in the seduction of Ar-Pharazôn, the twenty-fifth and last king of Númenor. Both Asmodeus and Sauron surrender to powerful human kings, but through guile, flattery, and promises of unfettered earthly power rise from captivity and virtual slavery to become the most trusted of royal advisers. Both subsequently corrupt their masters, leading them to war, false worship, and destruction. Both are aided in their usurping of power by all-powerful magical rings.

See also: AR-PHARAZÔN

ASTERIA The Titan goddess of falling stars and night oracles whose name means “of the stars” in Greek. She is comparable to Tolkien’s Ilmarë, handmaid of Varda, Lady of the Stars. Ilmarë is among the greatest of the Maiar spirits and her name, which may mean “starlight” in Quenya, appears to have been inspired by Ilmarinen, the Finnic smith-god who appears in the epic Kalevala.

ATHELAS A sweet-smelling herb with healing powers found in Middle-earth, which may have been inspired by basil. In Middle-earth, athelas is also known as kingsfoil or asëa aranion, meaning “leaf of kings,” in Quenya. The word “basil,” too, derives from the Greek for “king,” and in German the plant is sometimes known as Königskraut, or “king’s herb.” In Tolkien’s legendarium, the healing powers of the herb are believed to be greatly enhanced when royal hands apply it. In this, Tolkien was drawing on the ancient English and French tradition of “the healing hands of the king,” which dates at least to the reign of Edward the Confessor (1042–66). In the War of the Ring, Aragorn’s use of athelas to combat the deadly magic of the Black Breath after the Battle of the Pelennor Fields is seen by Gondorians as evidence that the king has returned to Gondor.

Athelas. The herbal lore attached to this herb relates to the European tradition of the “healing hands of the king.”

ATHENS The ancient Greek city-state—and its best-known mythical king, Theseus—are imaginatively linked to the city-state of Middle-earth’s Gondor. Both the citadel of Gondor and the Acropolis of Athens have comparable traditions of sacred fountains and sacred trees. In Athens, there was the Fountain of Poseidon and the Olive Tree of Athena, while in Gondor there is the Fountain of Minas Tirith and the White Tree of Gondor. Furthermore, the citadel of Gondor is similar in its basic structure to the Acropolis, including the ship-prow ridge that is a feature of both. From the heights of the Acropolis, the Athenians could look down on the Long Walls that linked Athens to its ports at Piraeus and Phalerum on the Aegean Sea, just as, from the heights of citadel, the citizens of Gondor can look down on the Great Wall that links the citadel to its ports on the Anduin River. In the siege of Gondor, toward the close of the War of the Ring, the appearance of black-sailed ships sailing upstream from the port-city of Umbar results in the suicide of Denethor, the Ruling Steward of Gondor. This was undoubtedly inspired by the ancient myth of Theseus, where the appearance of black-sailed ships from Crete results in the suicide of Aegeus, Theseus’ father and king of Athens. Both rulers mistake the black sail as signals of death and defeat when in fact their rescuers and heirs, Aragorn and Theseus, command the ships.

See also: BLACK SAILS

The Downfall of Númenor. The Downfall of Númenor was in large part inspired by Plato’s account of the ancient legend of the rise and fall of the mythical utopian island continent of Atlantis.

ATLANTIS The legendary island kingdom that inspired Tolkien’s tale Akallabêth, or “The Downfall of Númenor.” This was one very distinct case of Tolkien taking an ancient legend and rewriting it in such a way as to suggest that his tale is the real history on which the ancient myth was based. So that we do not miss the point, Tolkien tells us that the Quenya name for Númenor is Atalantë. Plato’s dialogues Timaeus and Critias are the primary sources for the Atlantis legend. In the Timaeus, Critias tells how the Athenian statesman Solon travels to Egypt where he learns the history of Atlantis. According to Plato, Atlantis lay in the ocean beyond the Pillars of Heracles (i.e., in the Atlantic Ocean) and that on “this island of Atlantis there existed a confederation of kings, of great and marvelous power, which held sway over all the island, and over many other islands also and parts of the continent.” In Tolkien’s retelling of the Atlantis story, the island continent of Númenor is located in the middle of the Western Sea between Middle-earth and the Undying Lands. Like Atlantis, Númenor is a fabulously rich and blessed realm whose kings wield great power and hold sway not only over all the island but, by dint of their fleets of mighty ships, over many parts of Middle-earth as well. The fate of Númenor is all but identical to that of Atlantis, as described by the first-century AD Hellenistic Jewish philosopher Philo, who wrote: “… in one day and one night [Atlantis] was overwhelmed by the sea in consequence of an extraordinary earthquake and inundation and suddenly disappeared, becoming sea, not indeed navigable, but full of gulfs and eddies.”

AULË In Tolkien’s Valarian god Aulë the Smith, the Maker of Mountains, we have the counterpart of the Greek god Hephaestus (the Roman Vulcan). Both are capable of forging untold wonders from the metals and elements of the Earth. Both are smiths, armorers, and jewelers. Like Hephaestus, Aulë is depicted as a true craftsman and artisan, someone who creates for the joy of making, not for the sake of possession or gaining power and dominion over others.

Aulë is also the maker of Tolkien’s race of Dwarves. These in their origins are very like the race of automatons created by Hephaestus, who appeared to be living creatures, but in fact were machines similar to robots designed to help in the smithy with the beating of metal and the working of the forges. In Tolkien, Aulë creates the Dwarves because he is impatient for pupils who can carry out his knowledge and craft. However, they are given true life and independent minds only at the command of Eru Ilúvatar. Among the Norsemen, Aulë’s counterpart as the smith to the gods and heroes is Völundr. Among the Anglo-Saxons, he is Wayland.

Aulë the Smith. His spouse is Yavanna the Fruitful.

AVALLÓNË A port and city on the “Lonely Isle” of Tol Eressëa, originally home to those of the Teleri Elves (the so-called Sea Elves), who came to Aman. Its name is reminiscent of Avalon, the “Isle of Apples,” to which the mortally wounded King Arthur is taken to be healed and given immortality. In a letter to a publisher, Tolkien acknowledged that this allusion was deliberately planned so as to give his Hobbit heroes, Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, an “Arthurian ending.” That is, like King Arthur, these Hobbit heroes sail off over the Western Sea to Avalon/Avallónë where they too find healing and are given immortality.

See also: AVALON

AVALON The isle to which the mortally wounded King Arthur is taken after the Battle of Camlann. In Tolkien we have its counterpart in Avallónë on Tol Eressëa, the “Lonely Isle” of the Teleri Sea Elves. Avalon means “Isle of Apples” and is comparable to the classical Garden of the Hesperides where the beautiful daughters of Atlas and Hesperis (“Evening”) tend the tree (or whole grove of trees) that bears the golden apples of immortality. A similar story can be found in Norse mythology, where Idunn, the goddess of youth, keeps golden apples that protect the Aesir from the ravages of time. The bittersweet ending of The Lord of the Rings—the departure of the Ring-bearers from the Grey Havens—is consciously modeled on the myths and legends surrounding King Arthur’s departure to the isle of Avalon. It is an ending that is derived from the Celtic aspects of the Arthurian tradition, rather than the Teutonic ones. After his final battle, the mortally wounded Arthur is carried onto a mysterious boat by a beautiful queen (or sometimes three queens) and taken westward across the water to the faerie land of Avalon, where he is healed and given immortality. This end to Arthur’s mortal life is very like the end of Tolkien’s novel. However, it is important to point out that this is not the end of Aragorn, the figure most like Arthur in The Lord of the Rings. Aragorn dies within the mortal world. The supreme reward of this voyage into the land of immortals is reserved for another. The “wounded king” who sails on the Elf-queen Galadriel’s ship across the Western Sea to the Elven towers of Avallónë is Frodo the Ring-bearer, the real hero of The Lord of the Rings.

AVARI The “Dark-elves,” or Avari, of Middle-earth were very likely inspired by the categorization of the two races of elves in Norse mythology who inhabited two distinct worlds: Alfheim and Swartalfheim. Alfheim was the “Elf home” of the light elves, while Swartalfheim was the home of the dark elves. These divisions are similar to those Tolkien imposed on his own race of Elves: the Calaquendi, or Light-elves, who live for the most part in the immortal lands of Eldamar; and the Moriquendi, or Dark-elves, who live in the mortal lands of Middle-earth.

See also: ALFHEIM

BB

Bats. Of the many creatures that Melkor the Dark Enemy bred in darkness, the blood-sucking bat was one. Sauron himself changed into a bat when he fled after the fall of Tol-in-Gaurhoth.

BAG END The Hobbit hole (smial) and ancestral home of the Baggins family of Hobbiton in the Shire. Bag End was the original name for Tolkien’s aunt Jane Neave’s Dormston Manor Farm, just a few miles from the author’s childhood home in the hamlet of Sarehole in what was then rural Worcestershire. The manor’s origins stretch back to Anglo-Saxon times, and it undoubtedly fired Tolkien’s imagination in his construction of the fictional world of Middle-earth. However, it was perhaps more than just his childhood memories that Tolkien drew on in his creation of Bag End. “I came from the end of a bag, but no bag went over me,” riddles Bilbo Baggins of Bag End in his contest of wits with the Dragon of Erebor. Just like the Hobbit, his creator was fascinated with puns, word games, and riddles, and by literary sleights of hand. Furthermore, there are elements of social satire in the name of Bag End. As the eminent Tolkien scholar Tom Shipley has observed, Bag End is a literal translation of the French cul de sac, a term employed by snobbish British real estate agents in the early twentieth century who felt the English term “dead-end road” was just too vulgar. Naturally, Tolkien’s very English Baggins family would have no truck with this kind of Frenchified silliness, and so decided upon this suitably authentic local English name of Bag End. As a rule, Tolkien despised the pretensions and snobbery that looked down on all things English. He preferred plain English in language, food, and culture. Calling the Hobbit home of Bilbo Baggins “Bag End” is the epitome of everything that is honest, plain, and thoroughly English. Through the Hobbits of Bag End, Tolkien both extols and gently parodies the Englishman’s love of simple home comforts, seen as both delightful and absurd. Overall, the only thing that seems surprising is that he didn’t write a parody aphorism along the lines of “The Hobbit’s hole is his castle.”

BAGGINS The family name of Tolkien’s principal Hobbit heroes in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. It derives from a double source—the English Somerset surname Bagg, meaning “money-bag” or “wealthy,” and the term “baggins,” meaning “afternoon tea or snack between meals”—and is certainly appropriate for a prosperous and well-fed Hobbit.

Initially, the “original Hobbit,” Bilbo Baggins, is presented as a mildly comic, home-loving, rustic, middle-class “gentle-Hobbit.” He seems harmless and placid enough, if given to a little irritability, and full of gossip, homespun wisdom, wordy euphemisms, and elaborate family histories. He is largely concerned with domestic comforts, village fetes, dinner parties, flower gardens, vegetable gardens, and grain harvests. However, once recruited by Thorin and his Dwarf Company, the respectable Bilbo Baggins is revealed—much to his own astonishment—to be a highly skilled master burglar.

Tolkien always maintained that his tales were often inspired by names and words, and indeed, in the jargon of the nineteenth-and early twentieth-century criminal underworld there is a cluster of terms around “bag” and “baggage” that link up with one or other of the various highly specialized forms of larceny. Three are especially noteworthy: “to bag” means to capture, to acquire, or to steal; a “baggage man” is the outlaw who carries off the loot or booty; and a “bagman” is the man who collects and distributes money on behalf of others by dishonest means or for dishonest purposes.

It appears, then, that the name Baggins not only helped to create the character of Tolkien’s Hobbit hero, but also went a long way toward plotting the adventure his hero embarks on. For, in The Hobbit, we discover a Baggins who is hired by Dwarves to bag the Dragon’s treasure. He then becomes a baggage man who carries off the loot. However, after the death of the Dragon and because of a dispute after the Battle of Five Armies, the Baggins Hobbit becomes the bagman who collects the whole treasure together and distributes it among the victors.

Along with the Baggins name, further “baggage” is passed on to Bilbo’s heir, Frodo Baggins. In the context of the One Ring, there is a link between the name Baggins and another specialized underworld occupation: the bagger or bag thief. This bagger or bag thief has nothing to do with baggage, but was derived from the French bague, meaning “ring.” A bagger, then, is a thief who specializes in stealing rings by seizing a victim’s hand and stripping it of its rings. It appears to have been in common usage in Britain’s criminal underworld between about 1890 and 1940.

Consequently, one might speculate that from the beginning the Baggins name contained the seeds of the plot of both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. For one step beyond Bilbo’s skill as a burglar, one might also conclude that—from the perspective of the Ring Lord (or indeed Gollum)—the Baggins baggers of Bag End, Bilbo and his heir, Frodo, are also natural-born Ring thieves.

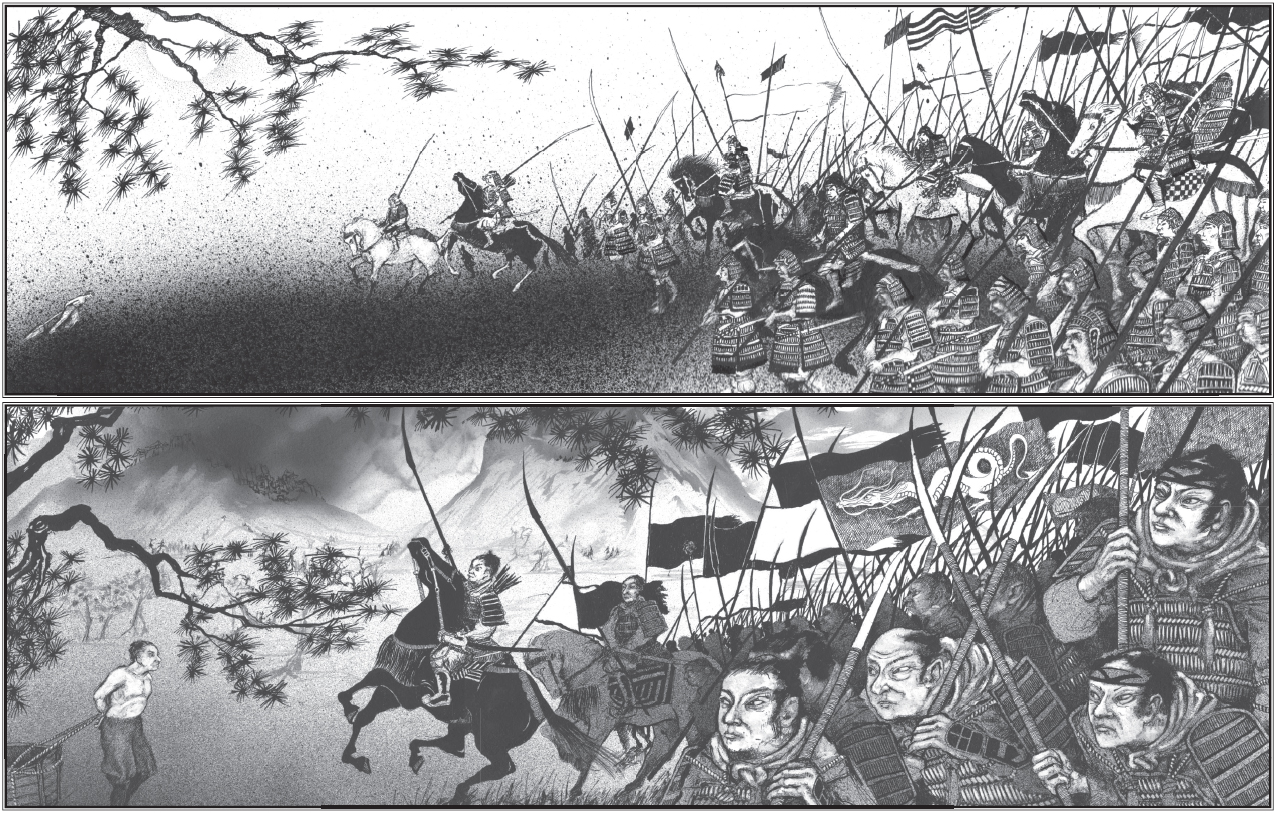

BALCHOTH A barbarian horde of Easterlings from Rhovanion which, in 2510 TA, invade Gondor and engage with the Gondorian forces in the critical Battle of the Field of Celebrant. The tide of battle turns against the Balchoth when, unexpectedly, the cavalry of the Éothéod (ancestors of the Horsemen of Rohan) join forces with the Men of Gondor.

This has an historic precedent in the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields in AD 451 when the Roman army formed an alliance with the Visigoths (West Goths) and Lombard cavalry and defeated the barbarian horde of Attila the Hun. This is considered one of the most critical battles in the history of Europe as it turned back what seemed an unstoppable wave of Asiatic conquest of the West. In Middle-earth, in the wake of the Battle of the Field of Celebrant, the Balchoth confederacies rapidly disintegrated, as did the Hunnish confederacies after the Battle of Catalaunian Fields.

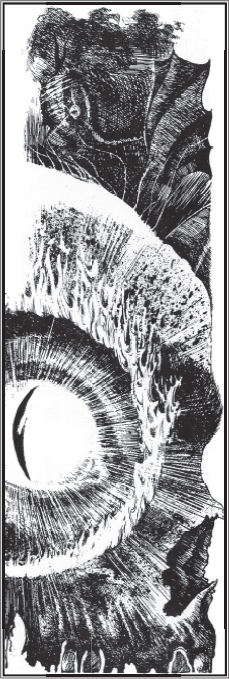

BALOR OF THE EVIL EYE King of a race of deformed Irish giants known as the Formorians. Balor’s name derives from the Celtic Baleros, meaning “the deadly one” suggestive of a spirit or god of drought and plague. He was also known as Balor Béimnech, meaning “Balor the Smiter,” and Balor Birugderc, meaning “Balor of the Piercing Eye.”

One of Balor’s eyes was normal, but the other was an evil eye that was so deadly that he opened it only when he was called into battle whereupon its searing glance would wreak terrible destruction on the opposing army. There are obvious affinities with the Eye of Sauron here, which is variously described as the “Evil Eye,” the “Red Eye,” the “Lidless Eye,” and the “Great Eye.” Unlike Balor’s Eye, however, it does not serve as a kind of supernatural artillery but has a psychic power and will that could overwhelm and conquer the minds and souls of servants and foes alike. As related in The Silmarillion, “the Eye of Sauron the Terrible few could endure.” Certainly, Christopher Tolkien concluded that, in the War of the Ring, his “father had come to identify the Eye of Barad-dûr with the mind and will of Sauron.”

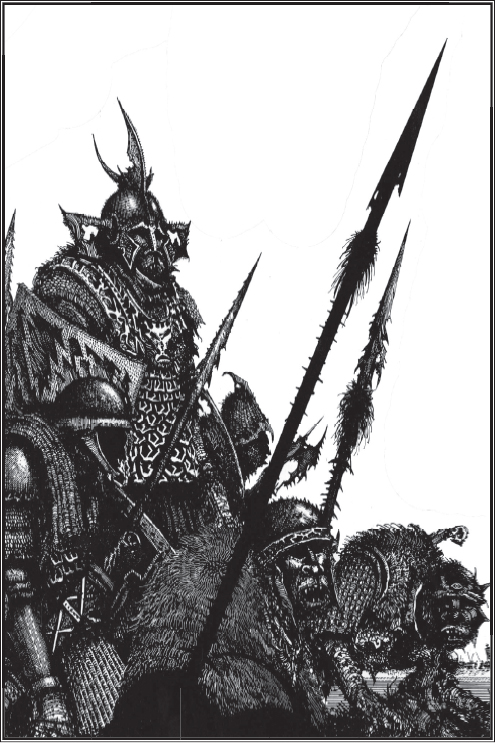

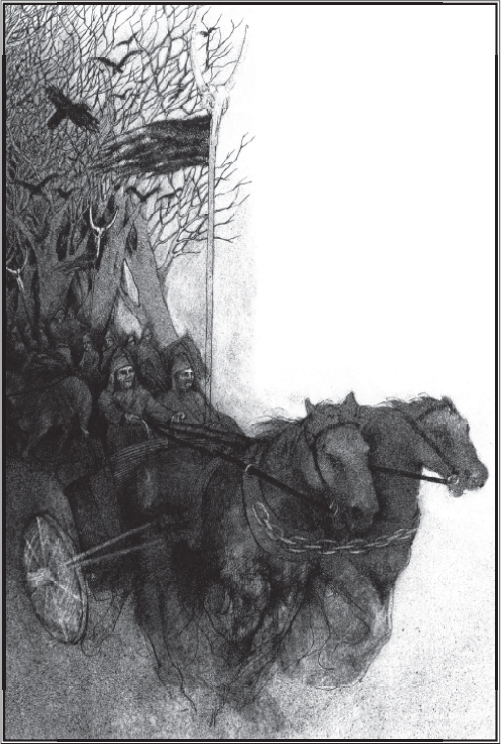

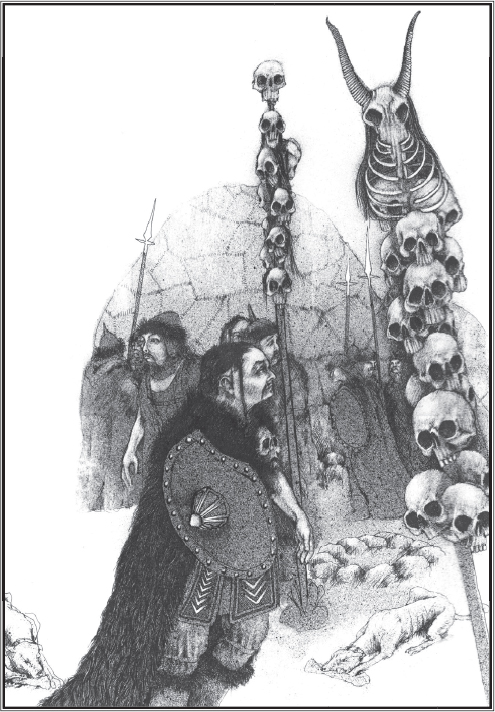

Balchoth. One of the many great Easterling peoples who harry and assail Gondor during the Third Age.

In all cultures, eyes are believed to have special powers and are said to be windows of the soul. So Tolkien’s description of the evil Eye of Sauron gives us considerable insight into the Dark Lord himself: “The Eye was rimmed with fire, but was itself glazed, yellow as a cat’s, watchful and intent, and the black slit of its pupil opened on a pit, a window into nothing.”

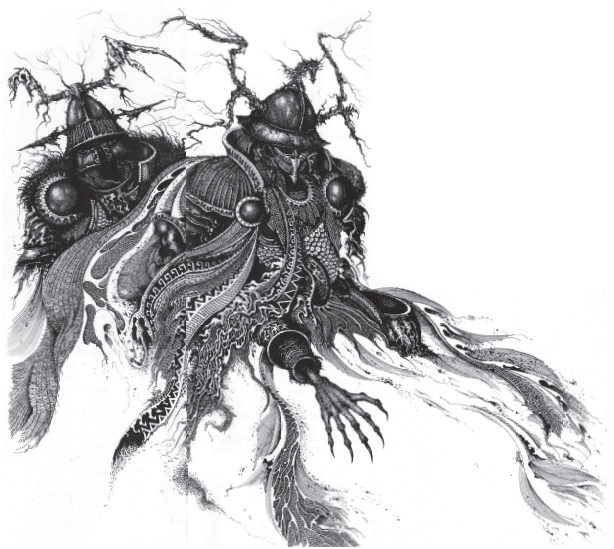

BALROGS OF ANGBAND Known as the Valaraukar or “Cruel Demons” in Quenya, these mighty Maiar fire spirits are among the most terrifying of Morgoth’s servants in the War of the Jewels. More commonly known to the Sindar of Beleriand as Balrogs, or “Demons of Might,” they take the form of man-shaped giants shrouded in darkness, with manes of fire, eyes that glow like burning coals, and nostrils that breathe flame. Balrogs wield many-thonged whips of fire in battle, in combination with a mace, ax, or flaming sword.

Visually, the Balrogs, while male, are comparable to the demonic Erinyes (Furies) of Greek mythology, female chthonic deities and avenging spirits—called Alecto, Tisiphone, and Megaera—who emerged from the pits of the Underworld to pursue those guilty of crime. Furies were variously described as having snakes for hair, coal-black bodies, bats’ wings, and blood-red eyes. They attacked their victims with blazing torches and many-thonged brass-studded whips. There can be little doubt, however, that Tolkien’s primary source for the Balrogs was the fire giants of Muspelheim, the mythical Norse “region of fire.” The giant inhabitants of Muspelheim were demonic fire spirits who—once released—were as unstoppable as the volcanic lava floes that were so familiar to the Norsemen of Iceland.

There is also a link with Tolkien’s Anglo-Saxon studies. Since Joan Turville-Petre’s publication of Tolkien’s notes on the Old English poem Exodus, several scholars have linked this text with his invention of the Balrogs. In these notes, Tolkien took issue with the usual modern translation of the Exodus’s “Sigelwara land” as the land of the Ethiopians. Tolkien believed that Sigelwara was a scribal error for sigel-hearwa, the land of “sun-soot,” and was instead a reference to Muspelheim. The Sigelwara therefore were the fire giants—in Tolkien’s own words, “rather the sons of Músspel … than of Ham [the biblical ancestor of the Ethiopians], the ancestors of the Silhearwan with red-hot eyes that emitted sparks, with faces as black as soot.”

Tolkien changed his concept of Balrogs over time, the fire demons becoming fewer, larger, and more powerful. Through multiple drafts, Balrogs dwindled from “a host” of hundreds or even thousands, down to “at most seven,” as noted by Tolkien in a curious marginal note. Whatever their number, by the end of the First Age, Tolkien informs us, the Balrogs were entirely destroyed in the War of Wrath “save a few that fled and hid themselves in caverns inaccessible at the roots of the earth.”

BALROG OF MORIA A nameless terror known only as “Durin Bane.” For over a thousand years of the Third Age, the menace of the Balrog keeps the Dwarves from their ancient kingdom of Khazaddûm, named during that time Moria (“black pit”). It is not until Gandalf’s encounter with the creature during the Quest of the Ring that its identity is revealed as one of the Balrogs, the monstrous Maiar fire spirits inspired by the fire giants of Muspelheim in Norse mythology. This particular Balrog is a survivor of the War of Wrath in the First Age, having hidden itself for millennia deep beneath the Misty Mountains. It is only by chance, or perhaps fate, that it is awakened by the deep-delving Dwarves of Khazad-dûm.

The monster’s tenure in Moria ends with the fateful Battle on the Bridge of Khazad-dûm. This battle between Gandalf the Wizard and the Balrog of Moria actually has a very specific precedent in the Norse mythological battle between the god Freyr and the fire giant Surt on the last day of Ragnarök. Both battles begin with a blast of a battle horn. In Tolkien’s tale, Boromir blows the Horn of Gondor, while in the Norse myth the god Heimdall blows the Gjallarhorn, the horn of Asgard. Like the Balrog of Moria who fights Gandalf on the Bridge of Khazad-dûm, Surt, the Lord of Muspelheim, fought Freyr, the god of the sun and rain, on the Rainbow Bridge that links Middle-earth to Asgard. Tolkien’s Bridge of Khazad-dûm and the Norse Rainbow Bridge both collapse in the conflict and the combatants in both battles topple into the abyss below. Surt and Freyr are entirely destroyed in this battle, while the Balrog and Wizard continue their struggle until the Balrog is slain, though at the cost of Gandalf’s bodily form as the Grey Wizard.

BARD THE BOWMAN In The Hobbit, the slayer of Smaug the Dragon of Mount Erebor, liberator of the Men of Esgaroth and first king of the new kingdom of Dale. Bard is an archetypal dragon-slayer in the tradition of the Greek god Apollo, patron of archers, who slew the great serpent Python, which lived beside a spring at Delphi and terrorized the people of the locality. Just as Bard the Bowman slays Smaug with his bow and arrow, so Apollo the Archer arrow slew Python and liberated the people of Delphi, enabling the god to take possession of its oracle.

See also: DELPHI

BARROW-DOWNS Low hills in Eriador crowned with megaliths, tumuli, and long barrows that are the ancient burial grounds of Men dating back to the First Age of Middle-earth. In the Third Age they become the Great Barrows of the kings of Arnor but in the wake of Arnor’s destruction, they are invaded and haunted by evil spirits.

Tolkien took his inspiration for the Barrow-downs from Britain’s monumental Neolithic earthworks and later Anglo-Saxon barrow graves, which in later times often became the focus of folktales and legends. The Neolithic long barrows and Bronze Age round barrows of Normanton Down, on a ridge just south of Stonehenge in Wiltshire, southwestern England, is one possible real-world source for Tolkien’s Barrow-downs. Another candidate is an impressive Neolithic site just 20 miles from Oxford, locally known as Wayland’s Smithy. Tolkien had visited the site in outings with his family and knew well the many myths relating to Wayland the Smith (the Old Norse Völundr), a Germanic figure who was inspirational in the creation of the Elven Telchar the Smith. Both were master sword smiths who forged weapons with charmed blades like those discovered by the Hobbits in the Barrow-downs.

In 1939, at about the time Tolkien was writing the opening chapters of The Lord of the Rings, archeologists made an extraordinary discovery in Suffolk of three Anglo-Saxon long barrow graves at a site called Sutton Hoo. Covering about 16 acres, the site had been occupied for more than three and a half millennia before becoming an Anglo-Saxon burial site. The excavation also revealed the richest treasure trove of Anglo-Saxon artifacts ever found. The discoveries at Sutton Hoo were as revelatory of the Anglo-Saxon world as the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb was of the ancient Egyptian world.

While Tolkien makes no mention of Sutton Hoo in his letters, it is hard to resist the idea that the Hobbits’ imprisonment by a Barrow-wight in one of the barrows and their discovery of ancient swords were in part inspired by the great discoveries at Sutton Hoo.

See also: BARROW-WIGHTS

Barrow-wights. The wraiths and spirits who haunt the graves and tombs of the dead are a fixture of many cultures.

BARROW-WIGHTS Evil undead spirits that animate the bones of entombed Men in the Barrow-downs of Eriador. Early in The Lord of the Rings, one of the Barrow-wights briefly imprisons Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin in a barrow until Tom Bombadil frees them.

The Barrow-wights are not an original Tolkien creation since they already had a long history, especially in the sagas of the Norsemen. These Norse tales tell of encounters similar to those experienced by the Hobbits in which evil spirits with terrifying luminous eyes and hypnotic voices hold unwary travelers captive. Having paralyzed a victim with its skeletal grip, the wight performed rituals around the body before finally dispatching him using a sword, as a kind of bloody sacrifice.

A belief in haunted tombs and the cursed treasures of the dead is among the oldest of superstitions and also one of the most widespread. Truly bloodcurdling curses (meant as a deterrent to grave robbers) have been discovered written on the walls of Egyptian tombs. Other examples can be found in ancient cultures as different and mutually remote as China and Mexico. The Anglo-Saxons, too, had similar beliefs: after all, it is the disturbance of a barrow grave that leads directly to the death of Beowulf, the greatest hero in Anglo-Saxon literature. It was just Beowulf’s bad luck that the guardian of this particular barrow happened to be a fire-breathing dragon.

BATS

See: VAMPIRES

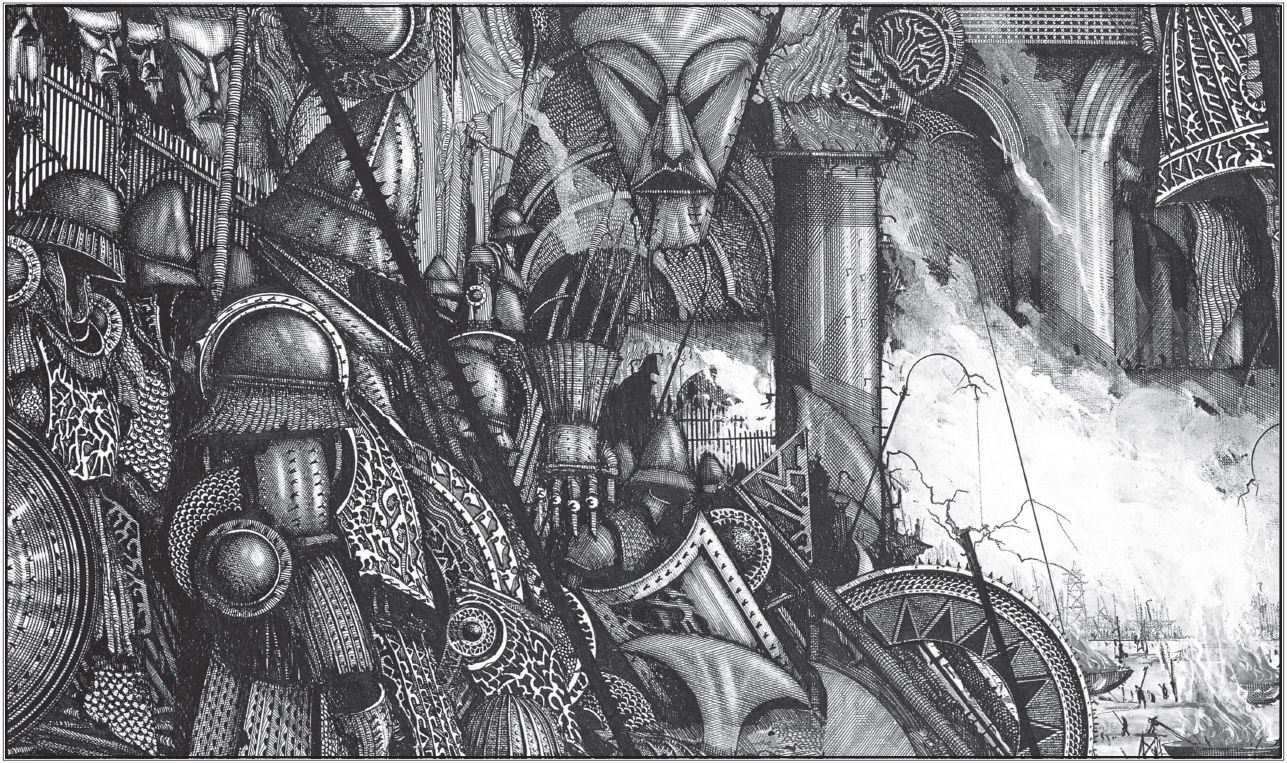

BATTLES Tolkien’s tales of Middle-earth abound in battles—from skirmishes and frays to cataclysmic conflicts of end-of-days proportions—and many have parallels with historic real-world battles as well as with those found in mythology and literature. The Battle of Dagorlad is comparable, in the utter destruction it wreaks and its massive body count, to the Battle of the Somme that Tolkien witnessed in 1916 during World War I. The Battle of the Field of Celebrant (between the invading Balchoth and the Men of Gondor and the Éothéod) has similarities to the Battle of Catalaunian Fields in which the Romans and the Visigoth cavalry allied against the Huns of Attila in AD 451. The Great Battle in the War of Wrath at the end of the First Age was, as Tolkien acknowledged, primarily inspired by the Norse myth of the final battle-to-be, known as Ragnarök. The Battle of Pelennor Fields, in The Lord of the Rings, is certainly the most spectacular and richly observed of all Tolkien’s battles and consequently has multiple parallels in, and allusions to, history, myth, and literature.

See also: CATALAUNIAN FIELDS; DAGORLAD; PELENNOR FIELDS

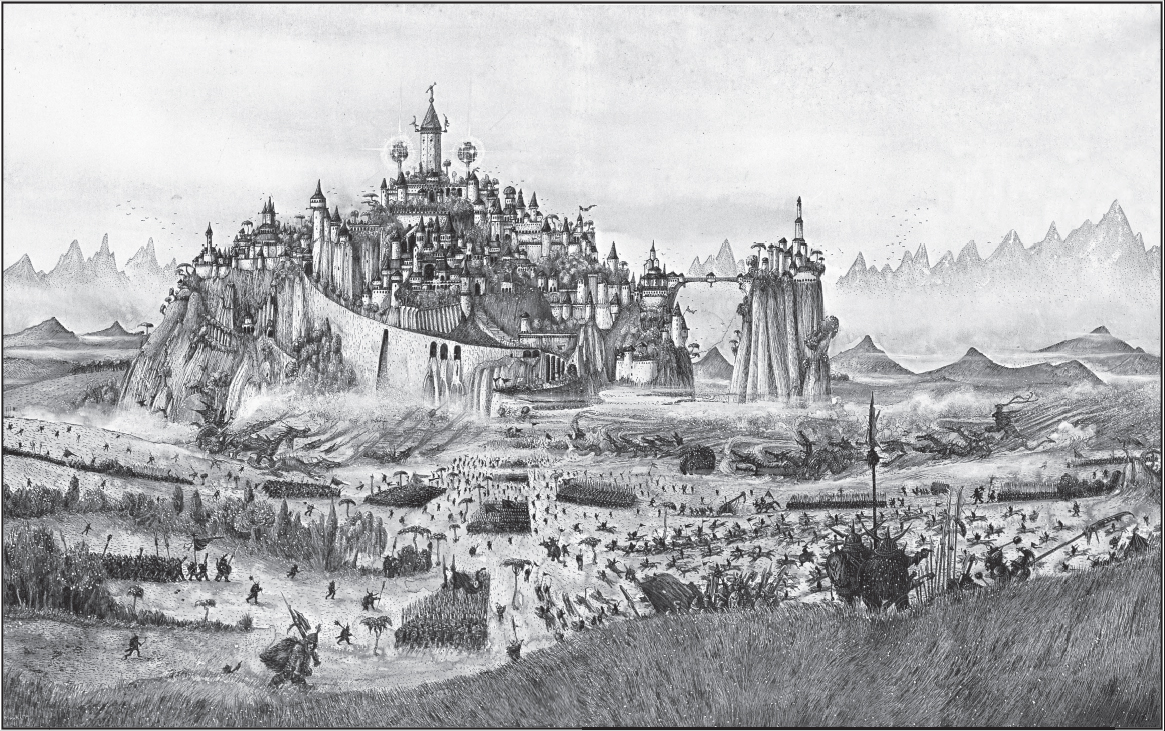

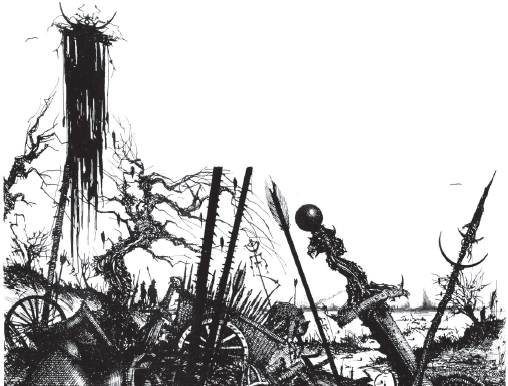

Battlefield. The carnage of the battlefield haunted Tolkien’s imagination.

BELEGAER The “Great Sea” that separates the mortal lands of Middle-earth from the immortal lands of Aman. This Western Sea was essentially inspired by the Atlantic Ocean, though as it was known or imagined in the mythology and legends of the ancient Greeks and Celts. The drowned island of Atlantis, the paradisical Fortunate Isles, inhabited by the Greek heroes after their deaths, and the Irish phantom-island of Hy-Brasil were all considered to lie somewhere in the Atlantic. All were inspirations for the islands of Númenor and Tol Eressëa.

BELERIAND In the First Age, a region in the northwest of Middle-earth that was home to several Elven kingdoms and cities, including Doriath, Gondolin, and Nargothrond. Toward the end of the First Age, during the War of Wrath, Belariand is largely destroyed and lost beneath the waves.

In Tolkien’s earliest drafts of The Silmarillion, his original name for Beleriand was Broceliand, obviously inspired by Brocéliande, the magical forest in Brittany, which features in many Arthurian tales. Tolkien’s conception of Beleriand—and especially the forested region of Doriath—owes a great deal to Brocéliande, which was closely associated with enchantments and perilous quests.

As a drowned land, Beleriand has parallels with the Welsh Cantref y Gwaelod in Cardigan Bay or the Cornish Lyonesse in the waters about the Isles of Scilly, two of the many “lost and drowned kingdoms” that abound in the Celtic legends of Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany.

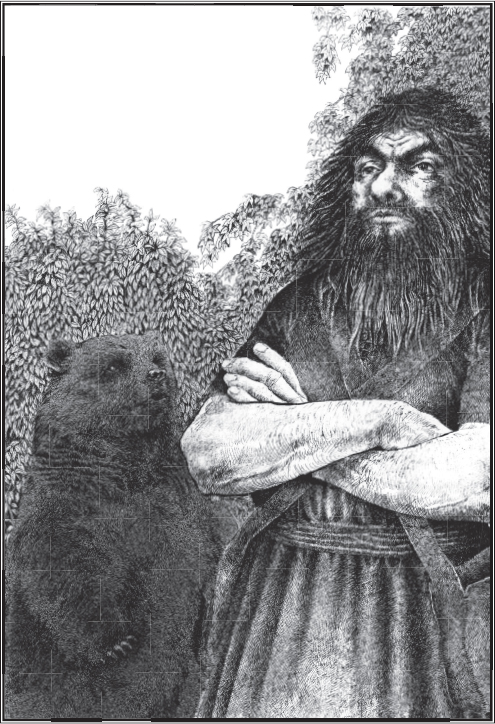

BEORN Eponymous chieftain of the Beornings who can take the form of a bear. In human guise, he is a huge, black-bearded man garbed in a coarse wool tunic and armed with a woodsman’s ax.

Beorn’s appearance in latter half of the The Hobbit establishes the fact that we are now firmly in the heroic world of the Anglo-Saxons, for he appears to be something approaching a twin brother of the epic hero Beowulf. With his pride in his strength, his code of honor, his terrible wrath, and his hospitality, Beorn is Beowulf transposed and brought down in scale. Even his home seems a smaller version of Heorot, the mead hall of King Hrothgar in the Anglo-Saxon epic poem.

Indeed, Tolkien gives his character a name that, while it sounds and looks a little different from Beowulf’s, ends up having much the same meaning, via one of the author’s typically convoluted philological puns. Beorn’s name means “man” in Old English. However, in its Norse form, it means “bear.” Meanwhile, if we look at the Old English name Beowulf, we discover that it literally means “bee-wolf.” What, we may wonder, is a bee-wolf? This is typical of the sort of riddle-names that the Anglo-Saxons liked to construct. “What wolf hunts bees—and steals their honey?” The answer is obvious enough: “bee-wolf” is a kenning for a bear: Beowulf and Beorn, then, both mean “bear.” Beorn, moreover, is a keeper of bees and a lover of honey. One might say that Beowulf and Beorn are the same man with different names. Or, in their symbolic guise as bee-wolf and bear, they are the same animal in different skins.

Furthermore, Beorn is a “skin-changer,” whose people are the likewise shape-shifting Beornings (the “man-bear” people)—Tolkien’s fairy-tale version of the historic berserkers (from bear-sark, or “bear-shirt”) of the Germanic and Norse peoples. When the berserkers went into battle, they performed rituals and acts of wild frenzy in an attempt to transform into the bears that they believed possessed them. Likewise, in the Battle of Five Armies, Beorn transforms from fierce warrior to enraged Were-bear, a miraculous event that turns the tide of this critical battle.

BEOWULF The most famous epic poem of the Anglo-Saxons, composed as early as the eighth century AD and surviving in manuscript form until the turn of the tenth and eleventh centuries. It was a touchstone for Tolkien’s writing both as an academic scholar and as a creative author. Tolkien acknowledged that the circumstances of Bilbo’s first encounter with the Dragon of Erebor were—at least subconsciously—inspired by a passage in Beowulf. In a letter to the English newspaper the Observer in 1938, Tolkien wrote: “Beowulf is among my most valued sources; though it was not consciously present to the mind in the process of writing, in which the episode of the theft arose naturally (and almost inevitably) from the circumstances.” While the two tales are not overtly similar, there are strong plot parallels between the dragon episode in Beowulf and the slaying of Smaug in The Hobbit. Beowulf’s dragon wakes when a thief finds his way into the creature’s cave and steals a jeweled cup from the treasure hoard. This scenario is duplicated when Bilbo finds his way into Smaug the Dragon’s cavern and steals a jeweled cup from the treasure hoard. Both thieves avoid immediate detection of their crime and the danger of the dragons themselves. However, nearby human settlements in the tales suffer terribly from the dragons’ wrath. Beyond this specific narrative parallel in The Hobbit, the influence of Beowulf is evident throughout Tolkien’s Middle-earth, in its landscapes, peoples, cultures, and languages, as well as in his use of language itself—the high epic tone of especially the last two books of The Lord of the Rings and Tolkien’s love of richly alliterative language and kennings.

See also: BEORN; DRAGONS; GOLLUM; ROHIRRIM

Beorn. One of the many characters for which Tolkien took his inspiration from Anglo-Saxon literature.

BEOWULF: THE MONSTERS AND THE CRITICS Tolkien’s most important and influential analysis of Anglo-Saxon literature, published in 1936. It was the first work by an Anglo-Saxon scholar to look at Beowulf’s literary value rather than its historic or linguistic aspects. Tolkien focused on the strong storytelling found in the epic and foregrounded the roles of Grendel and the Dragon, in which “the evil spirits took visible shape.” Even earlier than this study, between 1920 and 1926, Tolkien wrote his own rough translation of the epic, entitled Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary together with a Sellic Spell. This was posthumously edited by his son Christopher Tolkien, and published in 2017. Tolkien’s emphasis on the narrative power of Beowulf undoubtedly influenced his own storytelling craft.

BEREN One of the greatest heroes of the First Age of Middle-earth, and the character whose story (along with that of Beren’s beloved, Lúthien) was most meaningful to Tolkien himself. So great was the author’s identification with the hero that he had the names Lúthien and Beren included beneath his wife Edith’s and his own on their shared gravestone in Wolvercote Cemetery in Oxford.

Beren Erchamion and Lúthien Tinúviel are the central protagonists in the Quest for the Silmaril, the story of a mortal man’s quest for the hand of an immortal Elf-maid. As in many myths, legends, and fairy tales, the hero must prove his worthiness by achieving an impossible task, often set by the heroine’s father, who believes that the hero will die in the attempt. Here it is King Thingol who sets Beren the task of retrieving a Silmaril, set into the crown of Morhoth, who dwells in the evil fortress of Angband. To Thingol’s horror, Lúthien sets out on the quest alongside her beloved Beren.

As Tolkien freely acknowledged, the subsequent development of the tale was closely patterned on the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, only with the male and female roles reversed. In the myth, the musician Orpheus attempts to bring Eurydice back from the dead. Making his descent into the underworld, Orpheus plays his harp and sings to make the three-headed hound Cerberus, who guards the gates of hell, fall asleep. Brought before Hades, king of the underworld, Orpheus again plays and sings so beautifully that the god is moved to grant him the life of Eurydice, on condition that he does not look back at her as they make their way back into the land of the living. At the last moment, at the mouth of the tunnel, Orpheus cannot resist looking back at his beloved and she is taken from him and returned to Hades forever.

In Tolkien, it is Lúthien who, when the lovers reach the gates of the underworld-like fortress of Angband, lulls its unsleeping guardian, the gigantic wolf Carcharoth. It is she, too, who lulls Morgoth—the king of this underworld—to sleep (rather than moving him), enabling Beren to prize one of the Silmarils from Morgoth’s crown. Like Orpheus and Eurydice, Tolkien’s lovers fail at the last hurdle when Carcharoth wakes before the lovers can make their escape. At this point in the narrative, Tolkien departs from the Greek tale and introduces an allusion to the Norse legend of Fenrir, the Great Wolf of Midgard, who bites off the hand of the god Tyr when the gods bind him. Carcharoth, too, bites off Beren’s hand and swallows both the hand and the Silmaril he is holding. It is from this episode that Beren gains the epithet Erchamion, meaning “One Handed.”

To underscore the connection between the Greek myth and his tale, Tolkien duplicates the descent into the underworld motif by having Lúthien pursue Beren’s soul after his death. This time, in the House of the Dead in the Undying Lands, Lúthien exactly repeats Orpheus’ journey by singing to Mandos, the Doomsman of the Valar (a figure comparable to the Greek Hades), and winning from him a second life for her lover. Unlike Orpheus and Eurydice, however, Lúthien and Beren are allowed to live out their newly won mortal lives quietly. Thus, in the Quest for the Silmaril, Tolkien not only reversed the roles of Orpheus and Eurydice, but also overturned that story’s tragic end. In so doing, for a time at least, Tolkien allowed love to conquer death.

BERSERKERS The frenzied bear-cult warriors found in Icelandic, Norse, and Germanic cultures whose name derives from bear-sark, meaning “bear-shirt.” The berserkers inspired Tolkien’s depiction of the Were-bear Beorn in The Hobbit.

In their “holy battle rage,” the historical berserkers felt themselves to be possessed by the spirits of enraged bears. As Odin’s holy warriors, wearing only bearskins, they sometimes charged into battle unarmed, but in such a rage that they tore the enemy limb from limb with their bare hands and teeth. Such states, however, were essentially in imitation of what was the core miracle of the bear cult: the incarnate transformation of man into bear. Once again, Tolkien uses a name to inspire his imagination. Beorn’s name in Norse means “bear,” and in The Hobbit we soon discover that Beorn is a “skin-changer” with the power of transformation from man to beast and beast to man. It is a supernatural power that eventually makes Beorn a critical factor in the outcome of the Battle of the Five Armies.

BIFROST (THE RAINBOW BRIDGE) In Norse mythology the bridge that links Asgard, the immortal world of the gods, to Midgard, the mortal world of human. In the great final battle of Ragnarök, it is there that Surt, the fire giant of Muspelheim, takes up his sword of flame and duels with Freyr, the god of sun and rain. The battle seems to be the inspiration for the Battle on the Bridge of Khazad-dûm between Gandalf the Grey and the Balrog of Moria in The Lord of the Rings.

See also: BALROG OF MORIA

BILBO BAGGINS The first and original Hobbit created by Tolkien, the comic antihero of the eponymous The Hobbit who goes off on a journey into a heroic world. It is a world where the commonplace collides with the heroic, where the corresponding values clash to entertaining effect. In Bilbo Baggins, we have a character with whose everyday sensibilities the reader may identify, while vicariously having an adventure in a heroic world.

As Tolkien often observed, “names often generate a story”; they also nearly always contributed and suggested something of the nature or character of the person, place, or thing named. (We look at the influence of the character’s family name in the entry “Baggins.”) Another aspect of Bilbo Baggins’s character may be revealed by an analysis of his first name. The word “bilbo” entered into the English language in the late sixteenth century as the name for a short but deadly piercing sword of the kind once made in the northern Spanish port-city of Bilbao, from whence the name.

This is an excellent description of Bilbo’s sword, the charmed Elf knife called Sting. Found in a Troll hoard, Bilbo’s “Bilbo” can pierce through armor or animal hide that would break any other sword. In The Hobbit, however, it is our hero’s sharp wit rather than his sharp sword that gives Bilbo the edge. In his bids to escape Orcs, Elves, Gollum, or the Dragon, Bilbo’s well-honed wits allow him to solve riddles, trick villains, and generally get himself out of sticky situations.

When we put the two names together as Bilbo Baggins, we have two aspects of our hero’s character and to some degree the character of Hobbits in general. On the face of it, the name Baggins suggests a harmless, well-to-do, contented character (though with criminal undertones!), while the name Bilbo suggests an individual who is sharp, intelligent, and even a little dangerous.

BLACK GATE Morannon (“Black Gate” in Sindarin Elvish) is the great fortified iron gate in the stone rampart that bars the way into Mordor at the pass of Cirith Gorgor. There is a possible inspiration for the Morannon in the legendary Gates of Alexander, built by Alexander the Great in the Caucasus to keep out the barbarians of the north. However, the Morannon, which keeps out the civilized forces of Gondor and its allies, inverts this idea.

The Black Gate is the site of the terrible battle that closes the War of the Ring and sees the final overthrow of Sauron the Ring Lord and all his minions. In medieval German romance, this battle has a precedent in the famous battle between Dietrich von Bern and the forces of Janibas the Necromancer, who shares characteristics with both Sauron the Necromancer and the Witch-king of Angmar. Janibas appears in the form of a phantom Black Rider but commands massive armies of giants, evil men, monsters, and demons by the power of a sorcerer’s black tablet. This is comparable to the power and fate of Sauron’s One Ring in the Battle of the Black Gate. The ultimate contest comes when Janibas’s forces are about to overwhelm those of Dietrich’s at the gates to the mountain kingdom of Jeruspunt. In that moment the Black Tablet (like the One Ring) is destroyed and the mountains split and shatter and come thundering down in massive avalanches that bury the whole evil host of giants, demons, and undead phantoms forever.

BLACK NÚMENÓREANS Descendants of the King’s Men—supporters of Ar-Pharazôn, last king of the lost island-continent of Númenor—and sworn enemies of the Númenórean Men of Gondor and Arnor. After their settlement in the Númenórean colonies of Middle-earth, the Black Númenóreans—long corrupted by Sauron—continued to worship Morgoth and to flourish even after the downfall of Númenor. Their main center of power was the city, port, fortress, and empire of Umbar.

The portrayal of the Black Númenóreans of Umbar has clear similarities with the Punic inhabitants of the city, port, fortress, and empire of Carthage in North Africa. The Carthaginians had a rich, sophisticated culture, but their image in posterity has been largely formed by accounts written by their main rivals for dominance in the western Mediterranean, the Romans, who eventually destroyed Carthage in 146 BC. For the Romans, the Carthaginians were the barbarian “other,” whose practices —the worship of demonic gods and, most notoriously, the institution of child sacrifice—contrasted with and validated their own civilized values.

Black Númenórean

Similarly, in Tolkien’s works we typically see the Black Númenóreans through the eyes of the civilized Gondorians: they are lawless, being little better than pirates; they are worshippers of the Lord of the Dark, Morgoth/Melkor (whose name recalls that of Moloch, who is often identified with the Carthaginian chief god Baal Hammon); and they practice human sacrifice to Morgoth using fire, just as the Carthaginians were said to have burned children alive as an offering to Baal.

BLACK RIDERS Name given to the Nazgûl when Sauron sends them out on horseback to track down the Ring and its keeper, “Baggins.” They are the first truly evil entities to appear in The Lord of the Rings, in the green and pleasant Hobbit land of the Shire. The identity of these cloaked and hooded horsemen is not immediately revealed, but eventually they are proved to be the Ringwraiths. It is only later, through the eyes of the Ring-bearer Frodo Baggins, that the reader is given a glance of the Nazgûl as they appear to the Necromancer and those who inhabit the wraith-world. After slipping the One Ring on his finger, the Hobbit is suddenly able to see in the phantom shapes of the Ringwraiths their terrible white faces, gray hair, long gray robes, and “helms of silver.”

In some ways, the Black Riders are not unlike the phantom horsemen in the English poet John Keats’s ballad “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” (1819): a ghostly host of men seduced and enslaved by the “beautiful lady without mercy” of the title, and described as “Pale kings and princes, too, / Pale warriors, death-pale were they all.” The “palely loitering” kings and sorcerers who make up the Nazgûl have been similarly seduced, though not by the charms of a beautiful enchantress, but by Sauron and their overweening desire for power and a near-eternal life.

See also: HORSEMEN OF THE APOCALYPSE

BLACK SAILS At a critical moment during the Battle of Pelennor Fields in the siege of Gondor, black sails appear upon the Anduin River. It is an episode that mirrors the climax of the ancient myth of the Greek hero Theseus. In the Greek tale, the hero is revealed as the heir to the throne of Athens. His father, King Atreus, welcomes him back despite prophecies of regicide and patricide. When Theseus discovers that Athens must pay an annual tribute to the Minoans of seven youths and seven maidens as sacrificial victims, he decides to end this bloody payment. Theseus sets out in a black-sailed tribute ship to Crete where, along with 13 other young Athenians, he is to be sacrificed to the monstrous Minotaur in the palace of King Minos. With the help of Ariadne, the Minoan princess, he is able to slay the Minotaur, save his companions, and flee Crete.

On leaving Athens, Theseus promised his father that if he slays the Minotaur and releases his people from bondage, he would change the sails to white for his return voyage as a signal of victory. In the rush of his triumph, however, Theseus forgets his promise. Tragically, his father, the old king, sees the tribute ship returning with its great black sail still set. Believing his son Theseus to be dead, and his nation still enslaved, the old king throws himself from the high lookout prow of the Acropolis onto the rocks far below.

In The Lord of the Rings, Denethor, the Ruling Steward of Gondor, sees a mighty fleet of the black-sailed ships of the Corsairs of Umbar sailing up the Anduin River at a critical moment in the Battle of the Pelennor Fields. Believing that his son Faramir is dying of a poison wound, and that all his forces upon the battlefield are being overwhelmed and slaughtered, the Steward assumes that the black-sailed ships, and the reinforcements they carry, would make the defense of Gondor impossible. Mad with despair, Denethor commits suicide. However, like Theseus’ father, the Steward of Gondor is tragically mistaken.

In reality, Aragorn has been victorious: he has captured the black-sailed ships of the Corsairs, using them to transport fighting men from the coastal fiefs of Gondor and bring them to the Battle of the Pelennor Fields. It proves to be a decisive blow and turning point in the battle and the war. Just as Athens is freed from the threat of the tyrant Minos and Theseus succeeds his father as king, so Gondor is freed from the threat of the Witch-king, and Aragorn is restored as king.

Black Riders. The imagery of the Black Riders draws on popular representations of the figure of Death in Christian Europe.

BOROMIR Son and heir of Denethor II, Ruling Steward of Gondor. As a member of the Fellowship of the Ring, he survives many perils until the party reaches the foot of Amon Hen near the Rauros Falls. There, his desire to seize the One Ring from Frodo Baggins overcomes him. Although Boromir immediately repents, his actions result in the breaking and scattering of the Fellowship. Boromir sets off to look for Merry and Pippin and finds them surrounded by Orcs. He rescues them, but soon after an even bigger party of Orcs ambushes them. He fights valiantly to save them, but dies overwhelmed by the arrows of his enemies.

Tolkien’s account of Boromir’s heroic death is redolent of La Chanson de Roland. This, the best known of the medieval chansons de geste (songs of heroic deeds), is about Charlemagne’s most famous paladin, Roland, who makes his heroic last stand in the Roncevaux Pass in the Pyrenees while under attack from the Saracens. Ambushed and vastly outnumbered, Roland fights valiantly on until his sword breaks, and he is overwhelmed by the infidel hordes. As he dies, Roland blows his olifant (ivory hunting horn) to warn Charlemagne of the proximity of his foes. As Charlemagne hastens toward the pass, the Saracens flee, but the king is too late to save his liegeman.

Roland’s last stand is comparable to that of Boromir, Gondor’s greatest warrior, on the cliff pass above the Ramos Falls. Ambushed by a troop of Orcs and heavily armed Uruks, Boromir blows the Great Horn of Gondor. Aragorn, like Charlemagne, rushes to the site of the battle. The Dúnadan is too late to help Boromir, but is able to hear him utter a few last words of confession and to offer him hope and consolation. What marks out both scenes is a sense of ultimate victory despite the defeat of death.

“BRAVE LITTLE TAILOR, THE” A German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm, but found in many versions. The story tells of how a poor young man, alone and armed only with his wits, is able to overcome all obstacles and slay powerful but slow-witted giants or trolls. In The Hobbit the three Trolls encountered by Bilbo Baggins and Thorin and Company are very like the Grimm Brothers’ trolls. Although immensely stupid by human and hobbit standards, these Trolls—Bert, Tom, and William Huggins—are capable of understanding and speaking Westron (though they have very poor grammar!). This makes them geniuses among the Trolls of Middle-earth, and almost smart enough to put an end to the Hobbit’s adventure. In the Grimm version of the tale, the Tailor hides from sight and throws a stone at each of the dim-witted trolls, who then accuse one another of the deed. This results in a fight that ends with the death of all the trolls. This scenario is largely repeated in The Hobbit. Here, however, it is the Wizard Gandalf who throws the stones that keep the Trolls quarreling until the Sun rises and they are turned to stone. As an aside, Tolkien as narrator adds: “Trolls, as you probably know, must be underground before dawn.” Here he is alluding to a folk belief likely dating back long before the twelfth century when it was first recorded in the Icelandic poem “Alvíssmál” in the Poetic Edda. In The Hobbit, it is through this particular episode that Gandalf provides Bilbo Baggins with his first lesson in using his wits to outsmart larger and more powerful foes. As is typical in such fairy tales, the reward is a treasure hoard and the acquisition of weapons that prove essential in the adventures ahead. In this instance, there are three Elven blades: one lethal sword each for Gandalf and Thorin, and one dagger that serves well enough as a Hobbit’s sword.