In the case of ostrich feathers in particular, there were feather farms around the world dedicated to supplying the seemingly unending demands of the millinery and fashion industries. In the early 1900s, probably just about the biggest of these farms was to be found in the Oudtshoorn (pronounced ‘Oats–horn’) region of Western Cape Province in South Africa, often referred to as ‘the Jerusalem of South Africa’. Max Rose, who had arrived in South Africa as an immigrant in 1890 was, by around 1900, the undisputed feather baron in the region. Another successful player in the feather market was Isaac Nurick, whose family had also been immigrants, hailing from the Latvian town of Shavel.

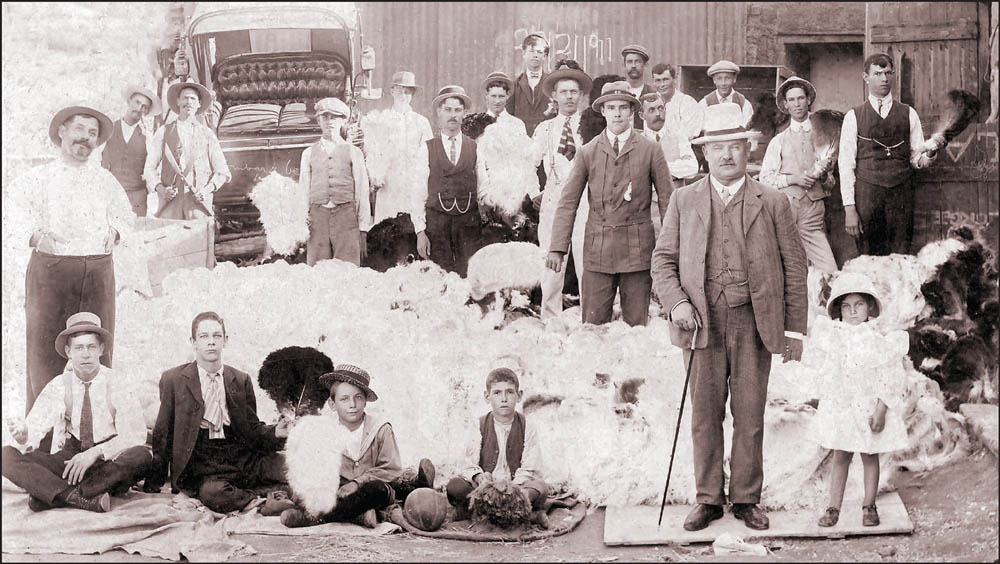

A 1911 picture of the Jewish feather dealer – Mr Isaac Nurick (pictured in the right foreground with the walking stick) and his daughter Ruby, together with around twenty of his staff and a large heap of feathers. Nurick’s story is one of rags to riches and back to rags again as he lost everything in a very short space of time when the world ostrich feather industry collapsed almost overnight. (Image by kind permission of the C.P. Nel Museum, Oudtshoorn, South Africa.)

The producers in this area, with a certain amount of cross breeding with the Barbary ostrich, produced superb ‘double fluff’ feathers – at least in the eyes of the milliners and over the late Victorian and early Edwardian periods, the owners had made immense wealth. Back in 1903 it was said that many feathers were fetching $32 per ounce and during 1912, it is claimed that £175 million worth of South African feathers were imported into Britain alone.

In her book, Plumes: Ostrich Feathers, Jews And A lost World of Global Commerce, Sarah Abrevaya Stein relates the story of how in 1911, in the search for the best ostriches and thus the best feathers, Russell Thornton, a South African government official, travelled to the Barbary area of North Africa (regions known today as Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria and Libya) with the aim of acquiring breeding pairs of birds to take back to his homeland. Things got a little complicated when no birds were located, but the search continued and some were subsequently located in the Sudan. Moving on to Kano in northern Nigeria – a major trading hub, Thornton and his team got back on track by examining the bales of feathers arriving on incoming Arab caravans. Having ascertained the origins of the good quality feathers, they eventually found what they were after in the French territory of Timbuktu. At this point, they were sanctioned by the South African government to purchase some 150 birds at a cost of £7,000. Then, having been banned by the French authorities from exporting said birds, there followed a cat-and-mouse scenario as the South Africans sought to outwit French ‘spies’ – which they eventually did. The ‘illegal’ consignment eventually made its way to the port of Lagos in Nigeria and from there, completed a further 3,000 mile sea journey to Capetown and the ostrich farms of Cape Western Province. Amazingly, some 140 birds survived the trip.

Some of the fortunes made from feathers by the breeders and dealers were translated into very splendid homes, which became known as ‘Ostrich Feather Palaces’ (see the following section). So sought after were feathers from this area that there was a time when just a single, fairly average, pair of these birds could fetch anything up to £1,000 and the feather industry became a significant part of the South African economy, being fourth only in export value behind diamonds, gold and wool.

An interesting 1907 article from Cape Colony To-day Illustrated by A.E.R. Burton (who gives the impression of not having been to an auction before) offers a very vivid account of the comings and goings at a feather auction of the time. In it he writes:

The conduct of a feather auction is very interesting. There are features about it different to ordinary auctions. For instance, a sale we attended was composed entirely of buyers. The feathers had been entrusted to the auctioneer as broker, and he represented most of the owners. Although the audience was most orderly, it was the keenest gathering imaginable. Jewish buyers in force, with a few slim farmers in opposition, and the cutest auctioneer in command. There were probably £8,000 worth of feathers for sale, so it was a fairly big sale. The first regulation read out was that there should be a reserve price on all feathers, and that they should be sold to the highest bidder above that price. The decision of the auctioneer was always to be final in case of a dispute, and all sales were for spot cash (nobody trusts anybody in the feather business). The attendance at a sale can only be secured by the introduction of an auctioneer and broker, a compound avocation, and from a local bank, and any person, other than the owner or the buyer, who wishes to attend must first be properly introduced by the broker or a responsible buyer. There were only three English firms represented.

This massive male ostrich was called Cetshwayo – named after the old Zulu king of that name due to his huge size. The bird became famous during the ‘Feather Boom’ period of 1891 when his owner received an amazing offer of £1,000 for him. This stupendous amount must be compared with the price of a five-seater Ford car in those days, which, according to the Oudtshoorn Courantin 1913 cost a full £200. Some bird! Some feathers! (Image by kind permission of the C.P. Nel Museum, Oudtshoorn, South Africa.)

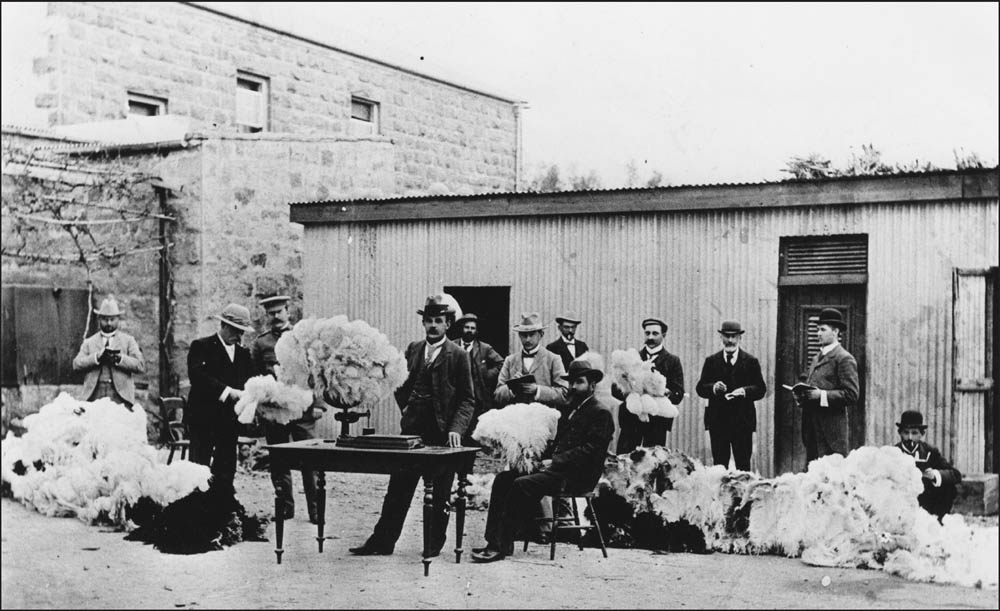

An interesting photograph of feather farmers and dealers busy buying and selling their ‘harvest’. The farmers in question were the three Potgieter brothers (pictured in the foreground) and various feather buyers feature at the rear. The man in the uniform is a security guard! £5,000 was made on that particular day. (Image by kind permission of the C.P. Nel Museum, Oudtshoorn, South Africa.)

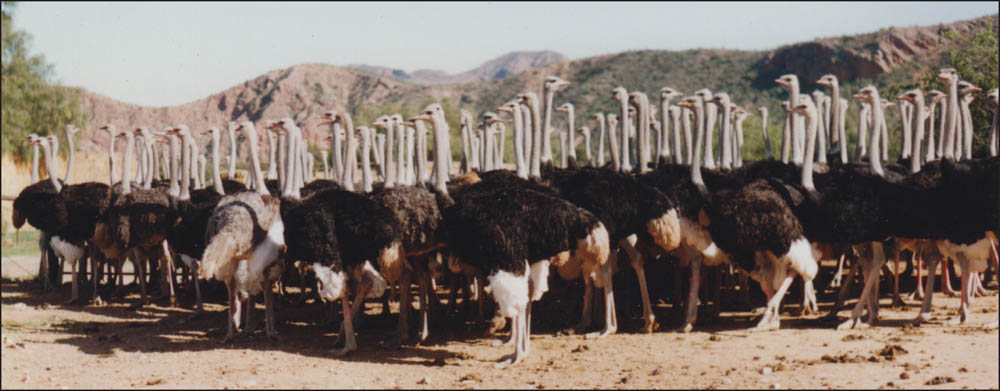

Ostriches on a modern day farm at the village of De Rust where a few farmers still produce beautiful feathers with birds descended from the original bloodline. (Image by kind permission of the C.P. Nel Museum, Oudtshoorn, South Africa.)

Mr Fanie Schoeman on the farm of Die Denne with a display of his prime feathers. Today, this farm is used as an experimental facility. (Image by kind permission of the C.P. Nel Museum, Oudtshoorn, South Africa.)

A happy day on 10 April 1912 at the upper class wedding of Emily Olivier and Dr Mathew Heyns. Emily was the daughter of G.C. Olivier – one of the feather barons in the Oudtshoorn area and owner of the ‘Towers’. The two bridesmaids with the amazing and elegant feathered hats were Muriel and Annie Foster. (Image by kind permission of the C.P. Nel Museum, Oudtshoorn, South Africa.)

Most of the feathers in the district are sold out of hand, while they are on the bird – sometimes three months in advance. The broker whose sale we attended informed us that his sales averaged over £60,000 a year. The profits made by individual farmers are enormous. One farmer lately contracted to sell to a local buyer his whole stock of feathers representing the plucking of 2,000 ostriches, at £6 per bird. This was only one of several interests he had. His tenants pay him £3,000 a year. Besides all this he has a large vineyard and orchard, and makes a lot of money out of dried fruit.

However, all ‘good’ things come to an end as they say and by 1911, with stiff competition from California, the south of France and other locations and the First World War fast approaching, the feather market started to wane. By 1913-14 when, it is estimated, there were around 776,000 ostriches being farmed, and with hostilities about to engulf Europe, the feather market collapsed as hats started to become smaller and less ornate resulting in warehouses around the world being full to the brim with feathers for which there were no buyers. These South African producers, many of whom were either part of, or associated with, the immigrant Russian Lithuanian Jewish community in that neck of the woods and who had been millionaires – or at least very financially well off – one day, suddenly found themselves in much reduced circumstances the next; the bubble, at that time, had just about burst. Isaac Nurick, whom I mentioned previously, lost pretty much everything; leaving his family behind, he ‘escaped’ to London where he reportedly died penniless. Another story records the reduced circumstances of a particular feather merchant who, in relating the speed with which he had been ruined, detailed how in 1914 he had had a cheque for £100,000 honoured by the local bank but only a year later, a cheque for just £1 had been refused. Dire times; but I bet the ostriches were having a quiet smile! Some reports from the period cynically suggest that certain feather warehouses ‘mysteriously’ burnt down and received insurance payments – but heaven forbid anything underhand!

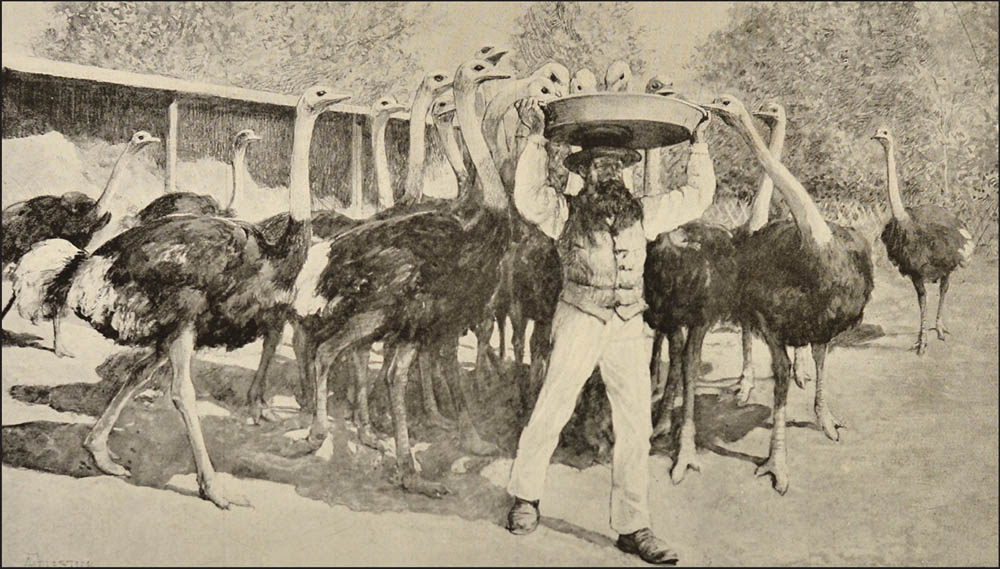

A very novel way to feed ostriches as depicted in this image painted at an ostrich farm at Meknès in Morocco by Anglo French artist – Sir Amédée Forestier 1854 – 1930. Although not originally native to North Africa, one can reasonably assume that, with France’s connections to the region, these birds were being reared for their feathers to supply the French millinery trade.

A century later, with the world’s population having increased many times over, South Africa is still the world’s largest producer of ostrich feathers (along with ostrich meat and skin for up market leather goods) although diseases such as bird flu in particular can wreak havoc in an industry which is once again a major contributor to that country’s economy. Figures from 2012 show that even though there is no longer a craze for large hats, except perhaps at certain race meetings and the like, there are still around 740 ostrich farms employing over 20,000 people which is quite remarkable. Even a cursory search will astonish the reader at the large number of both wholesalers and retailers around the world still offering these ostrich ‘adornments’. But the human race can be very odd and complex and for millennia, certain societies have, for one reason or another, felt the need to decorate themselves with the plumage of assorted colourful birds. For centuries, the traditional ‘sing-sing’ celebrations of the tribes of the general Borneo and Papua New Guinea regions, Amazonia and the North American Indians were great users of amazing feather bedecked headwear in one ceremonial way or another – but more of this later. In their day, the Edwardian’s were not exactly new to the game!

There’s an old English saying – mainly associated with the north of the country which goes – ‘Where there’s muck, there’s brass’ but in the case of the Oudtshoorn area, maybe that should be changed to ‘Where there’s feathers, there’s brass.”’ Crime, it seems, has no limits and in recent times, this part of the world has been plagued by ostrich feather theft. On 10 April 2013, it was announced by the police that five men would appear in court for the alleged theft of ostrich feathers over the previous five months – with an estimated value of R117, 000 (nearly £6,000). The thefts involved the stripping of feathers from numerous live ostriches and in some cases a number of the birds were savagely bludgeoned to death. One of the main targets has been the Western Cape government’s research farm at Oudtshoorn. The crime of feather theft has gone on for at least a hundred years – occasioning at one point, the 1907 introduction in South Africa of ‘The Ostrich Feather Theft Suppression Bill’ but it seems that some things (especially cruelty to our fellow creatures) have not changed that much over the last century.