Our Victorian and Edwardian forebears, especially the former, had a somewhat peculiar and unenlightened passion for taking birds from the wild. In late Victorian times a House of Commons committee was advised regarding the story of one boy who had captured an amazing 480 goldfinches in just one morning! This type of thoughtless activity together with the subsequent burgeoning trend for feathers and whole birds to be worn on ladies’ hats certainly did our avian friends no favours whatsoever. The caged bird trade also continued to be a worrying factor, which persisted on a large scale for many years and this too took its toll on bird populations. Taxidermy was also popular. Look around the contents of any upcoming antique auction and the odds are that you will find a glass case or two filled with an assortment of colourful stuffed birds.

A period of ten years or more – ‘the Age of Extermination’ as it has been referred to by historians – saw the slaughter, carnage and shockingly inhumane actions of the feather hunters, one of whom in the UK was said to have taken over 4,000 birds in just one year, is illustrated by the fact that sometimes the wings of birds, particularly gulls and kittiwakes, were simply ripped off whilst the birds were still alive and what was left of the hapless creature was simply thrown back into the sea.

But this slaughter was not new. In an essay in 2000, R.J. Moore-Colyer, refers back to the situation in the 1860s and details –

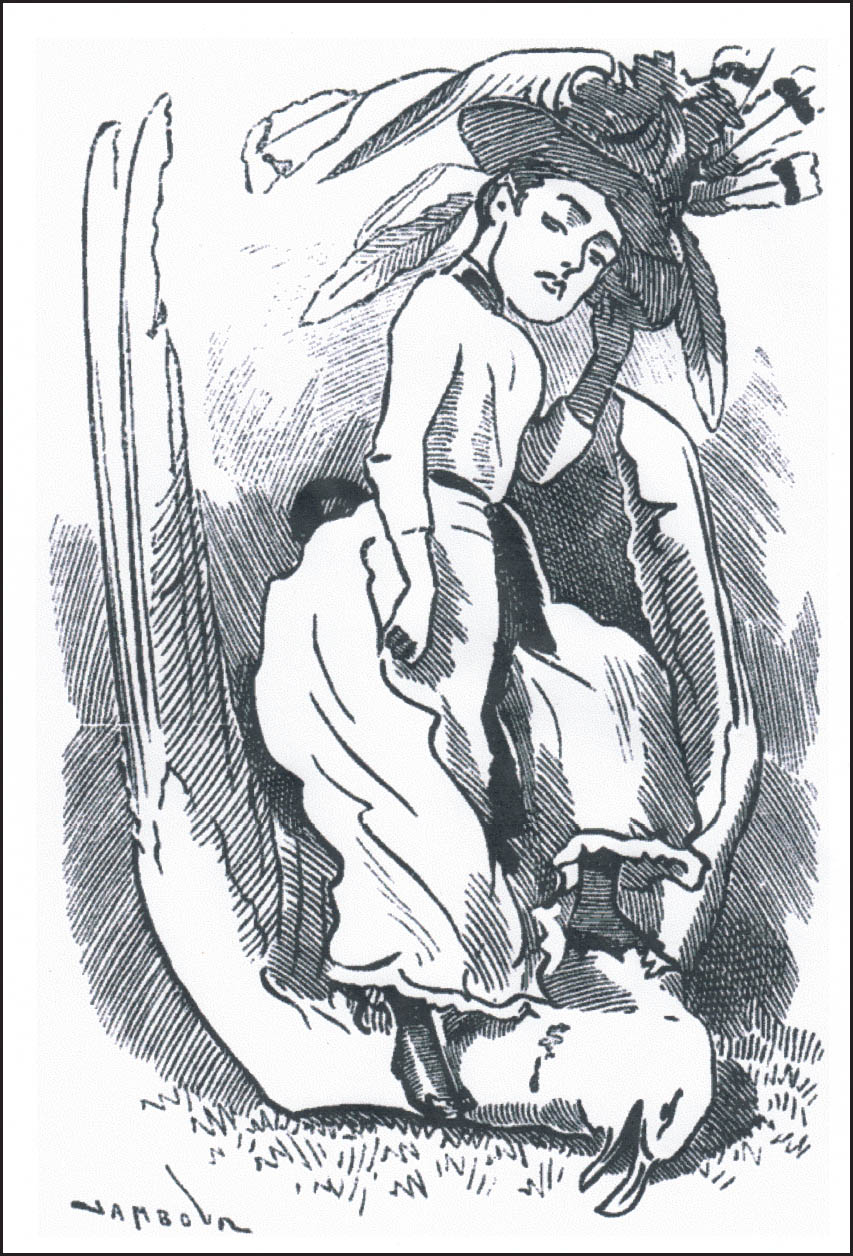

A rather macabre cartoon of the period drawing the association between the use of bird feathers on large hats and the destruction of birds which took place to get them.

As London and provincial dealers offered one shilling each for the wings of “white gulls”. . . excursion trains left London for locations as far apart as Flamborough Head and the Isle of White carrying beer-swilling plumage hunters and their rook rifles towards the killing grounds.

Even back in 1887 in the 17 September edition of the topical magazine Punch, a poem – author unknown, entitled ‘A PLEA FOR THE BIRDS’ (To the Ladies of England) floridly outlined the problem and concern.

It reads:

Lo! the sea-gulls slowly whirling

Over all the silver sea,

Where the white-toothed waves are curling,

And the winds are blowing free.

There’s a sound of wild commotion,

And the surge is stained with red;

Blood incarnadines the ocean,

Sweeping round old Flamborough Head.

For the butchers come unheeding

All the torture as they slay,

Helpless birds left slowly bleeding,

When the wings are reft away.

There the parent bird is dying,

With the crimson on her breast,

While her little ones are lying

Left to starve in yonder nest.

What dooms all these birds to perish,

What sends forth these men to kill,

Who can have the hearts that cherish

Such designs of doing ill?

Sad the answer: English ladies

Send those men, to gain each day

What for matron and for maid is

All the Fashion, so folks say.

Feathers deck the hat and bonnet.

Though the plumage seemeth fair,

Punch, whene’er he looks upon it,

Sees that slaughter in the air.

Many a fashion gives employment

Unto thousands needing bread,

This, to add to your enjoyment,

Means the dying and the dead.

Wear the hat, then, sans the feather,

English women, kind and true;

Birds enjoy the summer weather

And the sea as much as you.

There’s the riband, silk, or jewel,

Fashion’s whims are oft absurd;

This is execrably cruel;

Leave his feathers to the bird!

Seriously nasty stuff this and indeed, such was the rate of ‘kill’ or capture in those days that questions were raised in parliament at one point. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (which was originally founded in Didsbury, Manchester in 1889 by Emily Williamson, wife of the explorer Robert Wood Williamson, and known in its infancy as ‘The Plumage League’) was invariably to the fore in campaigning against the use of feathers, as was Eliza Phillips, one of their most prominent members. Having been awarded its Royal Charter in 1904 the RSPB, as it’s commonly known today, soon gained a number of influential members including the Ranee of Sarawak and the Dutchess of Portland who was to become the Society’s first president. The RSPB initially concerned itself with two basic tenets:

1) That Members shall discourage the wanton destruction of Birds and interest themselves with their protection.

2) That Lady-Members shall refrain from wearing feathers from any bird not killed for the purposes of food – the ostrich only excepted.

In 1908 there was also an attempt to get the Importation of Plumage (Prohibition) Bill through the House of Commons but it failed to get passed first time round and that particular victory was only achieved some thirteen years later in 1921 – some three years after the end of the First World War when the fashion for large hats smothered with feathers had all but waned anyway. Still, better late than never. In reality, the law didn’t actually come into full force until April 1922.

Despite the RSPB’s earlier successes in the late Victorian years, the feather trade, aided and abetted by the Edwardians, continued apace. As an example of the sheer scale, it was reported that in 1911, over 41,000 humming bird skins were sold in London alone. To counter the growing concern, the feather suppliers would often claim that the feathers they were providing were shed naturally by the birds but in almost all cases, this was absurdly untrue.

Even Queen Alexandra banned ladies from Court if they were wearing osprey feathers on their hats, although it seems like the poor old ostrich, receiving no specific protection, had got the Royal ‘thumbs down’ and drawn the short straw (or should I say the short feather) once again. Ostriches it seems were of somewhat less value than ospreys in bird society.

In July 1911, a group of RSPB supporters (in rather strange outfits) with placards/sandwich boards, marching in London in protest against the use of Egret feathers on hats. (Image by kind permission of The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.)

In 1906 at the Annual General Meeting of the RSPB, Royal support was evident in a letter from the queen herself in which she stated that she ‘never wears Egret plumes herself and will certainly do all in her power to discourage the cruelty practiced on these beautiful birds’ further offering the president of the Society – the Duchess of Portland full permission to use her name – ‘in any way you think best to conduce to the protection of birds’.

In their earlier days, the RSPB were more than pleased to have the support of Queen Alexandra in their fight against the use of feathers and the huge destruction of the bird population.

Similarly, in America, partly as the result of the growing unease of enlightened people such as the Boston socialites Harriet Hemenway and her cousin Mina Hall, the Audubon Society was formed in 1905, dedicated to the memory of French/American John James Audubon (1785–1851). A truly talented man and probably best remembered today for his magnificently illustrated book: The Birds of America. Audubon, who led an amazing life one way or another, was a highly respected ornithologist and naturalist, and arguably one of the very best bird illustrators that ever lived. But, some fifty years after his passing, as the war on birds continued apace, the Audubon Society, grew in stature and continually voiced its concern as many colourful birds both in that country and around the world were ‘harvested’ to the brink of extinction or at least very serious depletion.