Butchery of birds for either food or feathers is no new thing as the 1598 image of Dutch explorers killing parrots in Mauritius depicts. By the Edwardian era however, some 400 years or so later, it had become just about as bad as it could get. In 1908, the British government outlawed the commercial hunting of birds of paradise in the parts of New Guinea under their rule but sadly, it took the Dutch authorities another twenty-three years to follow suit in their own Dutch New Guinea.

Dutch explorers on Mauritius featured in this 1598 image, wreaking havoc on the local parrot population.

During the Victorian and Edwardian eras, birds of paradise paid the price for simply being what they were – colourful and attractive. Today, through the media, television and various wildlife programmes, we know them for what they are – beautiful and amazing creatures. But for several hundred years, these birds had been something of a mystery and the only known information about them came from the relatively few dried corpses and skins that made their way back to Europe. They had been spotted in wonderment by Magellan’s men several hundred years earlier in 1522 and although three skins (it is said) came back with them aboard the ship ‘Victoria’, little fact about these birds was known.

That started to change in 1854 when the naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace visited New Guinea to study them followed in 1876 by the Italian Luigi D’Albertis who, in his double volume account of his expeditions, related several brushes with curious natives. Thus, by the end of the nineteenth century, people were starting to become much more aware of these birds, especially those within millinery trade who saw their gorgeous feathers as money-making additions to their hat creations. The chase was on and, before more enlightened views held sway and society came to its senses, there was only going to be one winner with the poor old New Guinea birds of paradise – particularly the Greater Bird of Paradise, with its colourful tail feathers – very much on the losing side. All that carnage, just to satisfy the whims of fashion. The habits, lives, conservation and beauty of these birds were of no consequence to the hunters, and the odd surviving examples of Edwardian feather-covered hats on display in museums around the world today offer mute examples of what was really going on.

Grandiose names for the many varieties of birds of paradise were often the order of the day. Those that ‘christened’ them seemed to have taken the view that they should be named after various dignitaries and Royals of the period and we thus have the likes of Princess Stephanie’s bird of paradise, Count Raggi’s, Victoria’s Rifle bird, Prince Rudolf’s, Emperor and The King of Saxony etc. Between the years of 1905–1920, the export of their skins to the auction houses of London, Amsterdam and Paris was estimated to be between 30,000 and 80,000 per year with hunters from China, Malaya and Australia (to name just three) moving in to make their fortunes.

In New Guinea, described by some as ‘the land that time forgot’, the rain forest territory of the Yonggom people between the rivers OkTedi and Muyu was a popular and prolific hunting ground with the locals often using feathers as currency. In the ensuing years, and having established at least a modicum of rapport with the locals in terms of trading, peoples like the Yonggom would readily supply the birds of paradise in return for such things as axes, knives and other European ‘goodies’. The hunting season usually ran from April until September and the Yonggom knew that, during this period, mature birds would assemble in large numbers to display. Engrossed in their courtship displays, the birds were thus easy prey for the hunters who took full advantage. (For those with an interest in this particular field, there is a very interesting article from the Penn Museum by Stuart Kirsch, which covers the subject in much more detail.)

The Greater Bird of Paradise – a typical example of the amazing plumage to be found on numerous birds of paradise. Easy to see why the Edwardian milliners loved them for their colour and decorative value.

But it was not only in the rainforests of New Guinea that the destruction of birds for their feathers was so savage, and it would take a very perverse point a view to describe it in any other way. For the hunters in Florida’s Everglades in America there were no ‘closed’ seasons. The plumage hunters wrought utter havoc, many often resorting to the use of the almost noiseless rifles or small calibre guns to do their dirty work. As ornithologist William Earle Dodge Scott – curator of the Museum of Biology at Princeton, put it: ‘The almost noiseless Flobert rifle … whose report is hardly louder than the snapping of a twig.’

In another 1887 report by the ornithologist William Earle Dodge Scott, curator of the Princeton museum of biology and made bird collecting forays to Florida, he gives details of a scene of horrific slaughter which to came across.

The trees were full of nests, some of which still contained eggs, and hundreds of broken eggs strewed the ground everywhere. Fish Crows and both kinds of Buzzards were present in great numbers and were rapidly destroying the remaining eggs. I found a huge pile of dead, half decayed birds lying on the ground, which had apparently been killed for a day or two. All of them had the ‘plumes’ taken with a patch of skin from the back, and had the wings cut off; otherwise they were uninjured. I counted over two hundred birds treated in this way … I do not know of a more horrible and brutal exhibition of wanton destruction than that which I witnessed here.

The colourful Carolina Parakeet was just one of numerous breeds to suffer terribly. Apart from obtaining its feathers, it was considered an agricultural pest and was slaughtered in huge numbers. Forest clearance, which had started in earnest in the 1800’s did nothing to help its cause. And so after around 1860 it was little seen or reported and was deemed to be extinct by the 1920s. The plight of the shore birds of that area fared little better being reduced to just five per cent of their original numbers in a relatively short space of time. Egret feathers in particular were also popular, particularly those that were referred to as ‘nuptial plumes’, which were grown by the birds for courtship purposes each year. The fact that, unlike some birds, both the females as well as the males were blessed with beautiful feathers, meant that invariably both adults were killed for their plumes leaving the young both parentless and defenceless to die a lingering death. (One section of the popular Sears catalogue in 1911 even shows a whole page entirely devoted to bird wings which are described as ‘Bargains in Imported Trimming Wings’ – on offer from thirty or forty cents to a dollar or two).

On this subject, ornithologist and conservationist T. Gilbert Pearson recalled:

A few miles north of Waldo, our party came upon a little swamp where we had been told herons bred in numbers. Upon approaching the place the screams of young birds reached our ears. The cause of this soon became apparent by the buzzing of green flies and heaps of dead Herons festering in the sun, with the back of each bird raw and bleeding … Young herons had been left by the scores in the nests to perish from exposure and starvation.

The American Ornithologists Union, founded in 1883 and similar to its British counterpart (founded in 1858) referred to: ‘Women as a Bird Enemy’. On another occasion in 1886, the growing danger to numerous bird species had been overtly illustrated to Frank Chapman of the American Museum of Natural History in New York as he walked through Manhattan on a couple of occasions – spotting the feathers of forty-two different native species on 542 passing ladies’ hats. Although it took a further twenty years or so, the New York State Audubon Plumage Law was enacted in 1910, which banned the sales of feathers from native birds and the importation of ‘aigrettes’ and other feathers. Previous to this, the Lacey Act of 1900 had helped the situation to a degree, as did the Migratory Birds Treaty Act in 1918. Nevertheless, in spite of the objections, and with feathers having risen from $32 per ounce to $80 per ounce by 1903, the trend seemed unstoppable.

The Lacey Act of 1900 had bolstered existing laws in that it prohibited interstate trade in wildlife and wildlife products (in this case feathers) protected by state legislation. Numerous states had protected their own native birds from the feather hunters who, in response, strove to get around the law by transporting their ill-gotten gains to states where the birds were not regarded as native, and sell them there. If they were caught and found guilty, both the seller and receiver would be hit with cripplingly onerous fines.

One of the first and more notable violations of the Act took place in 1909 and was perpetrated on Laysan – a tiny island in the Pacific some 808 nautical miles north-west of Honalulu in Hawaii. A German immigrant and feather merchant cum entrepreneur by the name of Max Schlemmer – often known as the ‘King of Laysan’ (and at other times ‘Schlemmer the Slaughterer’) hired twenty-three Japanese labourers to slaughter over 300,000 slow moving and clumsy Laysan and Blackfooted Albatrosses which were nesting on the island. Absolutely no mercy was shown and many simply had their wings hacked off and were left to die, while numerous others were simply herded into a nearby cistern and left to starve to death. Discovering what was going on, a zoology professor from the College of Honalulu informed the US authorities (Layson being part of US territory) whereupon the Secretary of the Navy immediately dispatched a revenue cutter (the Thetis) to the island, there to find carcasses, bones and three large containers of wings, feathers and skins. Utterly unforgivable.

Fabulous red plumes – a ready target for the feather dealers, fashion houses and milliners of Europe.

The guilty parties were immediately arrested and sent for trial in Honalulu. Later that same year, President Theodore Roosevelt was prompted to issue an Executive order creating the Hawiian Islands an official reservation for birds.

Gradually, at least some feather hunters saw the error of their ways. In his book Everglades Lawman: True Stories of Game Wardens in the Glades published by the Pineapple Press, James Huffstodt relates:

The plume hunters left devastation and the stench of decay in their wake. Even some hardened shooters were soon sickened by the brutal execution. One plume hunter, who would later quit the bloody trade, was consumed by guilt as he surveyed the hideous aftermath of an hour’s work. ‘The heads and necks of the young birds were hanging out of the nests by the hundreds’ he wrote. ‘I am done with bird hunting forever’.

A Damascene conversion if ever there was one!

Not everybody in high places was against the feather trade however, and numerous politicians spoke out against the reduction – citing the loss of jobs and employment. During the course of a debate on the Tariff Bill in 1913, a certain, (seemingly uncaring) American Senator by the name of Reed said:

I really want to know why there should be any sympathy or sentiment about a long-legged, long-beaked, long-necked bird that lives in the swamps and eats tadpoles and fish and crawfish and things of that kind; why we should worry ourselves into a frenzy because some lady adorns herself with one of its feathers, which appears to be the only use it has.

And that has to be just about as callous and unenlightened as anybody can get.

On another occasion, the outcry against the slaughter of birds for millinery purposes by the American public was countered as being ridiculous by the publication Milliner and Dressmaker which, in its wisdom, cautioned that ‘the result of any ban on the use of feathers would be to deprive hundreds of respectable young women of their livelihood in the trade.’ So that makes it OK then?

Although the Edwardian period had passed, this more recent picture shows two members of the South African feather industry in action at the 1924/25 British Empire Wembley Exhibition. The lady on the left is almost certainly Queen Alexandra (who died in that same year) observing the clipping of ostrich wing feathers with the bird secured in a ‘plucking box’. This demonstration was pretty certainly set up in an effort counter anti-feather campaigners such as the RSPB and to show that the process didn’t harm the birds in any way when the feathers were ‘harvested’. Note how the ostrich has a bag over its head. (Image by kind permission of the C.P. Nel Museum, Oudtshoorn, South Africa.)

In the UK, fairly similar sentiments were raised by a certain Lieutenant Colonel Archer-Shee, a London member of Parliament, who, when speaking in the Commons against the Plumage Bill of 1920, noted that many of his fellow MPs had themselves arrived at the chamber clad from head to toe in animal products such as fleeces of sheep, shoes made of cattle hide, rabbit-skin hats and with some even sporting the odd mink coat. What about the cruelty involved in obtaining those particular materials he pondered? Surely, the killing a ‘few’ birds to satisfy female fashion was but a drop in the ocean of cruelty? Other members expressed sentiments along the same lines.

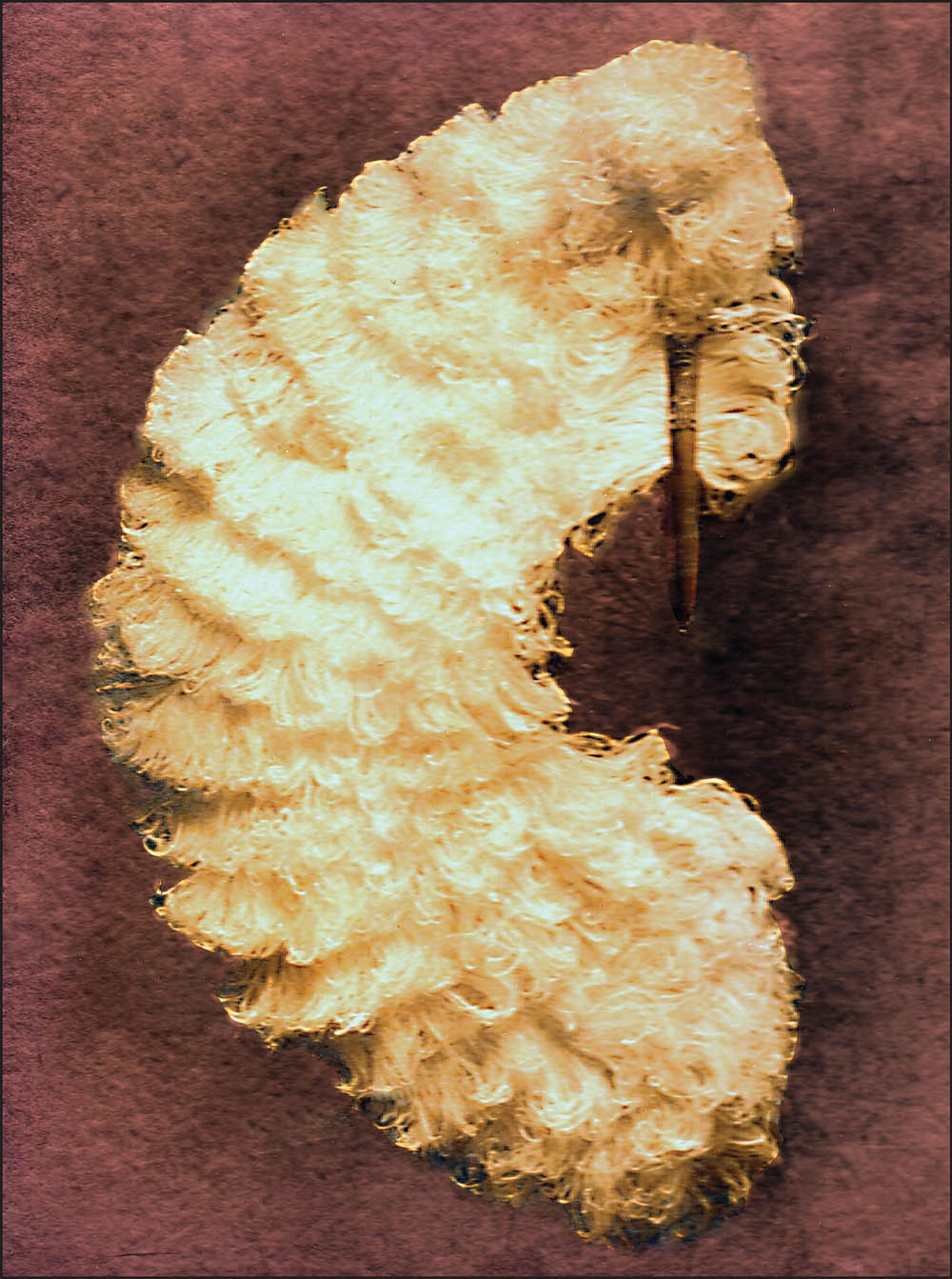

An ostrich feather fan presented to Her Majesty Queen Alexandra at the opening of the Cape Exhibition in London 1907. (Image by kind permission of the C.P. Nel Museum, Oudtshoon, South Africa.)