The Secret Journal of Doctor Watson

Author’s Note

Many of the characters in this book are historical personages. In this narrative, as well as in history, all were at their posts as described herein.

- The Romanovs, The Imperial Russian Family

- George V, King of England

- Sidney Reilly, SIS (Secret Intelligence Service) Master Spy

- David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of England

- Vladmir Illyich Lenin, Head of the Bolsheviks

- Arthur Balfour, Foreign Secretary

- Father Storozhev, local priest at Ekaterinburg

- Sir George Buchanan, British Ambassador to Russia

- Admiral Alexander Kolchak, “The Whites” Supreme Leader

- Thomas Preston, British Consul at Ekaterinburg

- Arthur Thomas, British Vice-Consul at Ekaterinburg

- Yakov Yurovsky, Commandant at the Ipatiev House

- Alexander Beleborodev, Bolshevik Commissar of the Urals Soviet

- Count Otto Von Mirbach, German Ambassador to Russia

- Major General Frederick C. Poole, Supreme Commander,

- Allied Invasion Force, Archangel

Preface

My name is Dr. John Watson. The grandson and namesake of the Dr. John H. Watson who wrote the remarkable stories about his adventures with Sherlock Holmes.

My practice is at 43 Dover Street, Kensington. I’m affiliated with St. Bartholomew’s Hospital. I was born on December 28, 1954 in London; my wife, Joan, was born here, as well. We have two sons: Jeffrey, age twenty, and James, age nineteen.

I never knew my grandfather as he died before I was born, but in 1993, he spoke to me. Across seventy-five years of history, his voice came through as clear as if he spoke to me directly.

I came into possession of a journal kept secret as per his instructions. What he wrote will irrevocably change a major piece of world history; that is, if you wish to believe him. I, of course, absolutely do.

My grandfather, from everything my family told me, and from everything I’ve ever heard or read about him, was an extraordinarily decent, loyal, loving and truthful individual. That he cared about people is evident from the fact that he was a physician. And if he wasn’t such a damned good one, my father wouldn’t have followed in his footsteps.

The whole world knows the care and love that my grandfather put into his stories about Holmes. The love he had for that man is palpable in every word, every syllable and every punctuation mark. Everyone knows the pains my grandfather went to in order to make sure that the truth of each adventure was recounted faithfully.

From every bit of evidence available, it seems that my grandfather was incapable of telling a lie. In fact, the one person in the world who knew that better than anyone else, my grandmother Elizabeth, used to laugh as she told me stories of how grandfather would jumble his words, head down, trying not to lie about some horrible new crime to which Holmes had made him privy. She said she’d purposely ask him about the more grisly details just to see how boyish his discomfort would make him; and that she’d finally release the poor man from his torment with what she called “a private laugh heard only by him.”

I still miss her. She’s been gone now over thirty years, but she made my grandfather seem as alive as she was. So even though I never knew him, I knew him better than most.

Therefore, what my grandfather wrote to me is no lie. Yet it’s so absolutely incredible, that even my solicitor advises against its retelling. Which is why I haven’t gone public before today.

However, my grandfather left that decision entirely to me, and I’ve made it. After a brief description of how I came into possession of my grandfather’s secret journal, I’ll simply let the words of his journal speak to you as his words have spoken the truth to unimaginable millions since his first published adventure with Sherlock Holmes.

On the afternoon of August 10, 1993, while I was still in my Kensington office, I received a telephone call from Wyatt & Stevens, the solicitors who had handled my grandfather’s affairs, and who, like a family heirloom, were passed down to my father, and then to me. I’m personally represented by Christopher Wyatt, the grandson of Alistair Wyatt, the man who directly represented my grandfather. And like our fathers before us, Chris and I have been friends since very early childhood.

In this day and age, that two families should share such continuity, and that two grandsons should maintain the same business relationship is probably without equal. Be that as it may, that tight family bond has served me very well.

After the usual pleasantries, Chris told me to be at his offices at five minutes to midnight, August 12. At first I thought he was playing with me.

“Chris, you’re joking. What are you talking about?”

“John, I have a sealed package here from your grandfather. It was sealed in 1920 and my grandfather was told that it was to be opened by Dr. Watson’s eldest surviving descendent at one minute after midnight on August 13, 1993. I haven’t the faintest idea what’s inside because we weren’t made privy to its contents. But my father told me he hoped your father had lived long enough to open the package.”

“Why didn’t my father tell me about this?” I asked.

“Because he didn’t know. Had he lived, I would be contacting him now and not you. In fact, from what I know, not even your grandmother was aware of this package. From the day your grandfather passed it into the possession of my grandfather, no one ever spoke of it again. Since your grandfather wasn’t the cloak-and-dagger type, whatever’s inside must be exceedingly important.”

We both laughed at that one because of my grandfather’s relationship with Sherlock Holmes. But I knew what Chris meant. My grandfather was not a secretive man.

I thanked Chris, hung up, and though I had patients piling up in my waiting room, I sat in my chair for the longest time trying to puzzle this out.

My wife, of course, expected exotic treasure hidden away from some extravagant Holmes sojourn. But I sensed something else. I didn’t know what, but I just didn’t think I was going to uncover the Kohinoor’s equivalent.

Anyway, I awaited the date as anxiously as the birth of both my boys. Here was a mystery of my grandfather’s making. I reported to Chris’ offices an hour before time.

Chris was there alone to greet me, laughing at my early arrival, but refusing to let me open my present before my birthday, so to speak.

What he did do, though, after handing me a much needed whiskey and soda, and I’m not sure if he did this to calm me or to torture me further, was to seat me in his private office, in his personal chair, and set the package down on his desk right in front of me.

It wasn’t a fancy-wrapped package or any of the sort like that, but rather a fairly flat package, wrapped in thick, plain paper with the texture of burlap, and wax-sealed with my grandfather’s personal stamp: a solemn “JHW” in the middle of the Hippocratic insignia. And when I first placed my hands on it to feel it, I knew instantly it was a book or journal of some kind.

Until exactly one minute passed midnight, Chris stood there watching me intently watching my package. Then with a happily taunting, “Good luck, John,” he closed the door behind him.

The second he left, I split the seal and slipped the contents from the wrapping. I was thrilled and disappointed. I guess that some part of me did wish for fabulous wealth, which at a glance wasn’t there.

But from the moment I opened the journal and read the first words, I knew I had something that paled the wealth of the Punjab. For there, in the unmistakable, erratic scrawl of the physician, was easily the most sensational Dr. Watson and Sherlock Holmes adventure of all.

My Secret Journal

My dear descendent, first, please do forgive me for so concise a salutation, but I know not who you are, what you are, or even if you are. For as I write this journal in the midst of a winter less harsh than the Great War it is immediately following, not only are you not as yet born, but my son John is a happy boy of only twelve. Would that the events I shall shortly convey be half so happy.

Secondly, I again beg your forgiveness for the lateness of the hour at which you were asked to appear, but as you read on, you will learn that I desired this information to be yours at the literal moment it could be yours.

What I am about to reveal to you could not be revealed until now. The Official Secrets Act forbids the divulgence of information considered a state secret, or of vital importance to the state, or of detrimental nature to the state for a period of seventy-five years after the fact. And the information I reveal is not only all of those, but considerably more. For what you shall now learn runs contrary to every history book in every country, contradicts everything you have learned as a good subject of the Crown, and would, if made public, bring the wrath and condemnation of the world down upon England’s ears. And since I know that you will be seated safely in my solicitor’s office as you read this, I have no fear that you will fall over from the shock you are about to receive.

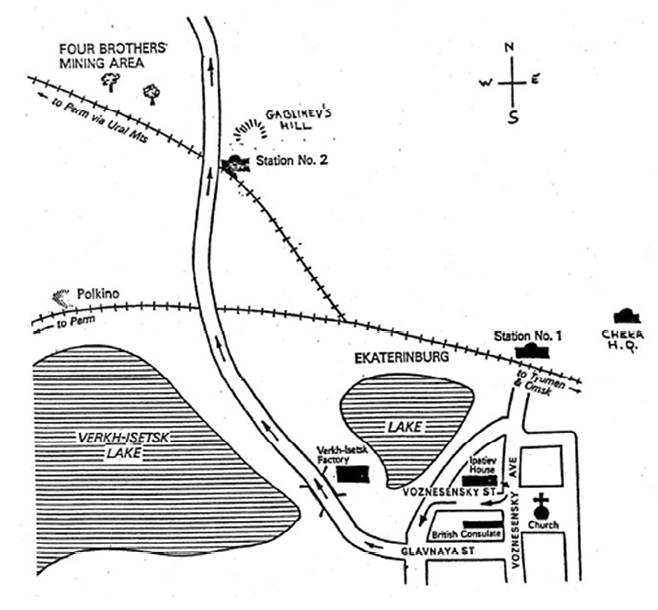

The world has been taught that on the night of July 16, 1918, in the Ipatiev House in Ekaterinburg, Siberian Russia, Tsar Nicholas II, the Tsarina Alexandra, and their children, the Tsarevich Alexei, and the four Grand Duchesses, Olga, Marie, Tatiana and Anastasia, were brutally executed by the local Bolsheviks.

It is a lie. A damnable, perfidious, perversion of the truth. Of paramount importance that it be believed at the time, it became sire to a family of lies so hideous, so twisted, so cynical, that I cursed my heritage as Englishman.

How do I know this? Because it was Mr. Sherlock Holmes, and me, who were sent to effect the Romanovs’ rescue. And you shall learn later from this journal the events as they truly transpired.

And though I wrote of Holmes’ quiet retirement to Sussex in 1903, he lost his life many years later in the midst of rendering the greatest of services to a beloved Sovereign.

Now then, the truth about that searing, Siberian summer, when the Russian world was Red or White, and millions were dying to decide the fate of seven miserable people. The Romanovs.

June 13, 1918

Early this morning, so early the sun had not yet risen, while my wife and I slept quietly at our home in Queen Anne Street, contentedly unaware of the conscious world, someone pounding against our door awakened us, sending my wife into an extremely anxious state and me into a headlong race down the stairs, shouting as I ran, for the pounder to cease.

You can imagine my utter amazement at opening the door and finding none other than Mr. Sherlock Holmes. Somewhat stunned I opened the door wider and he swept passed me and into my home.

“Watson, Watson, Watson...” was all he could manage while his frenzied dance continued unabated.

From upstairs Elizabeth called down, “John, are you all right? Who was it?”

“Holmes, my dear. It is only Holmes.”

“Mr. Holmes? At this hour? What ever is the matter?”

“I don’t know yet, my dear. Holmes is behaving rather peculiarly; even for Holmes.”

“Are you all right, then?”

“Quite, quite. Please return to bed. Everything will be explained presently, I’m sure.”

“All right, John. Give Mr. Holmes my regards.”

I conveyed my wife’s greeting to Holmes and asked him to sit. He did so, taking a seat by the fire while I took the one opposite.

Holmes’ face showed the shared, yet contradictory, emotions of exultation and dread uncertainty. I’d never seen such a look on Holmes, nor on any other human being. It startled and frightened me, and kept me silent until Holmes spoke again.

“Watson, without a word of explanation from me, if I were to ask you to accompany me on a journey so secret that you cannot even confide in Mrs. Watson, and so dangerous that our lives would certainly be imperilled, would you agree?”

I surprised myself at my own answer, for it came like an involuntary reflex, or the at-attention response to the command of a superior officer in the field, “Yes, sir.”

Holmes openly laughed, “Sir?”

Though embarrassed, I was full of curiosity, “Holmes, what is this all about? What is so perilous that it requires that you assault my door?”

“My friend, we are about to begin a task that might even have daunted Hercules.”

“Hercules did not have your brain, Holmes.”

He laughed, “And at my age now, I have not his strength.”

It seemed an odd remark for Holmes to make since he had always held brain in much greater regard than brawn. Nor had he ever confided a question of age; though both he and I were no longer the young men of our early adventures. And since I then intently studied his face for signs of physical strain or ill-being, and found none, it was something else that worried me.

For the first time since I’d known him, Holmes seemed to be struggling with a restless doubt.

Then, so quietly as to be almost a whisper, he said, “Watson, we are going into Russia.”

“Russia?” I shot upright, “Russia?”

Holmes’ eyes widened at my response. But again, and with a small nod, he said resignedly, “Russia.”

“But why Russia? There’s a civil war on that makes our war against Germany look like croquet! They’re slaughtering themselves with such gleeful insouciance as to make Attila envious. They’re barbarous, Holmes, barbarous! I know that I said I’d follow you, but this is suicidal recklessness.”

I was quite agitated now, and Holmes, knowing me as well as I thought I knew him, waited until I calmed down.

“But why, Holmes, why? Why Russia?”

And then, with the most calm, measured and determined of tones, with placid eyes to match, Holmes looked at me and said, “Because that is where we are needed, my friend. That is where we are needed.”

Holmes’ Astonishing Tale

Holmes then set about recounting the unbelievable events of the previous night. Had this tale been told by any other, I would have immediately sought the man a room in an asylum.

Holmes told me that at precisely twenty-two minutes past nine on the previous night, as he pensively fiddled in the study of his quiet villa that he claimed commanded a great view of the channel, he was shaken to see a rather large man with a deathly serious look on his face suddenly appear in the room. This man was in the company of a man even larger than he, and with equally grey a visage.

Holmes realised that he had no immediate fear of the duo since had they been intent on doing him any degree of harm, they would already have done so. Indeed, Holmes was now utterly intrigued.

“Yes, what do you want?”

“You are to dress, Mr. Holmes, and come with us!”

“I am, am I? Just who are you, and to where am I to accompany you?”

The larger of the two took a step towards Holmes.

“Get dressed, sir. We have our orders.”

“I must say, gentlemen, for two such hulking individuals, you caught me quite unawares in my meditations. If I did not suspect your true profession, I might profess the both of you to be involved with ballet, so ginger were your movements.”

Holmes said that the remark quite passed over their heads, which was probably just as well, considering the size and sheer density of the two.

Holmes asked the two if they would wait while he dressed in his bedroom, assuring them that he had no intention of making an escape, so keenly had they piqued his curiosity. But it was to no avail. They followed him upstairs and waited as he dressed himself.

As Holmes proceeded, he asked in half-jest if there was a particular manner in which he should dress; formally, for hunting, morning coat, etc. And he was quite surprised when a serious answer came back.

“Dress so as not to embarrass yourself before your betters.”

As soon as he had dressed, the two took Holmes bodily, each holding an arm, down the stairs and into a large, black motor car with drawn curtains sides and rear.

The motor car was then driven to Eastbourne Station where a train was waiting. Homes noted just a locomotive and one passenger car with all the curtains drawn.

Holmes turned to the smaller of the two and said “Well, well, what a lovely idea; a train ride in the middle of the night. Charming. But you should have told me, so I could have packed. Will this be a long journey?”

The two men said nothing, physically escorted Holmes aboard, sat him down, one on either side, didn’t say a word and stared straight ahead.

“And I don’t suppose you would be so good as to tell me where this train might be taking me?”

The larger one then said “Home, Holmes” and laughed. The other just smirked.

“Very humorous, indeed,” Holmes said.

The length of the journey was approximately one and one-half hours, and, as he had suspected from the moment he saw the train, he was now at Victoria Station. He and his unwanted companions made their way outside where another black motor car was waiting.

From the direction in which they seemed to be going, and the time quickly elapsing, he was convinced that he was heading towards a rather unexpected destination.

After driving for precisely twelve minutes in the middle of the night, in the middle of the capital of a nation at war, the motor car stopped. And as Holmes alighted, held again by “his nannies,” as he later called them, he was happy to find himself in front of perhaps the most celebrated address in all England, save for Buckingham Palace, 10 Downing Street.

Holmes wasn’t precisely sure if he was delighted to be at 10 Downing Street because it confirmed his sense of direction or deduction, or because he now knew for certain that he was in no danger.

The door opened before the trio as if triggered by their movements, and Holmes was brought through the hallway and led into the office of no less a personage than the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, who stood there, obviously awaiting their arrival.

It was now a few minutes past midnight.

The moment Holmes and “his nannies” entered the room, he was released from their grips and the two closed the door behind them.

“Prime Minister.”

Lloyd George, all nervous business, did not return the courtesy, and though Holmes was not overly surprised to find the Prime Minister at the end of his midnight journey, the reasons for it still intrigued him, and what happened next most assuredly did surprise Holmes.

Lloyd George, still without a word, opened a door to an adjoining chamber, and with the greatest conservation of gesture, bade Holmes enter that chamber.

In the darkened room, only two objects made themselves immediately discernible to Holmes. The first, a fireplace with intricately carved mahogany gargoyles framing a fire too large even for this uncommonly cool June night.

The second, and the most arresting, was a rather oversized wing chair facing the fire, hiding almost entirely its occupant; except for a perfectly manicured right hand grasping the arm of the chair so rigidly as to turn the tightened appendages almost white.

Holmes noticed the solitary ring on the hand, but before even his lightning mind could grasp its significance, the figure rose awkwardly.

Sherlock Holmes, the king of consulting detectives, now stood face to face with none other than His Imperial Majesty, George V.

“Mr. Holmes, so very good of you to come.”

“Your Majesty, under the circumstances, I had very little choice.”

“Yes, quite so. I do apologize for any inconvenience or disturbance you have been put through. Please sit down.”

Holmes waited for His Majesty to seat himself, and when he did not, neither did Holmes, a fact not even noticed by the King, so deep was His Majesty’s pondering.

“Mr. Holmes, what I am now about to ask of you must be asked by me and me alone. My government can have no official knowledge of this request, and you should know that it was I personally who asked the Prime Minister to summon you to me. Mr. Holmes, I want you to solve perhaps the greatest riddle of your life, and, quite possibly, prevent the greatest crime in history...”

“I understand perfectly,” said Holmes calmly, “you want me to rescue the Tsar and his family!”

King George stared at Holmes in amazement.

“But Mr. Holmes, how did you, how could you...”

“Your Majesty, it is not a feat of Olympian magic, I assure you, but simple logic.

“To be summoned to 10 Downing Street in the middle of the night, I need not have been of significant intelligence to deduce that whatever the government wanted of me, had to be kept in the strictest confidence. And upon meeting with Mr. Lloyd George personally, I, of course, knew that whatever the matter, it was of utmost national importance.

“Upon seeing your fingers so powerfully dug into your chair, I immediately knew that whoever you were, you were deeply disturbed and desperately groping for a seemingly unreachable solution to the matter aforementioned or you would not be here in this room.

“I would have to be an imbecile to be ignorant of your extremely close, familial and personal relationship with His Imperial Majesty, the Tsar, and an oaf to be unaware of the threat to not only his life, but to that of his family, as well.

“As soon as you mentioned a riddle and the prevention of a monstrous crime, it was not so great a leap to deduce the predicament.”

It was at this point that His Majesty broke his tone to whisper to himself, “Alexei, Alexei, poor little Alexei.” There was a brief and uncomfortable moment before the King again spoke.

“Mr. Holmes, because of who I am and what England stands for, I cannot officially ask my government to aid the Tsar and his family.” Here, the King’s anger began to rise with every reason he set forth to Holmes.

“I am reminded, by the Prime Minister, that I am a constitutional monarch, that we are still in the midst of the worst war our nation has ever endured, that the British people are happy at my cousin’s misfortune, that there is, and will be more, violent social unrest here at home, and that because of these things, the government cannot be placed in the position of being a tyrant’s saviour. That my own first cousin and his family should perish rather than reach safety on English soil. Does my own government not know that I am aware of these things? Do they suspect of me a limited intelligence, happily to limit myself to mere functions of ceremony? By God, Mr. Holmes, no subject ever felt chains as biting as mine at this moment.”

The King had now turned to face Holmes directly, his eyes fixed fiercely on Holmes’, a look, Holmes later said, “of commanding Majesty.”

Perhaps for the only time in his life, Sherlock Holmes was held mesmerized.

“Mr. Holmes, I am fully aware of the great service you rendered unto your country in what your Dr. Watson called ‘The Naval Treaty’; and that alone has given you valuable grounding in the delicate and arcane realm of international diplomacy. But you have remained outside of government, retired, untainted, and there would be no reason to suppose another involvement at this time.

“I shall not appeal to your patriotism. I shall not appeal to your loyalty as my subject. But I shall appeal to your sense of humanity and ask you to believe me when I say that in all the Empire, it is you alone who can accomplish this miracle.”

His Majesty finished speaking and took a small, gentle step towards Holmes, his eyes still holding Holmes as fixed as a fly in a web. Then he upturned both hands towards Holmes.

“Will you help me, Mr. Holmes?”

The question was a command; quiet and calm, yet a command nonetheless.

“I will, sir.”

The Bargain

As Holmes walked back out into Lloyd George’s private office, the Prime Minister seemed as nervous as ever. And this time, he spoke.

“Well, Mr. Holmes, quite a lot for one evening, I surmise.”

“Indeed, Prime Minister.”

“Mr. Holmes, when you helped the government with that nasty naval business, I was not yet Prime Minister, as you know. My philosophy on certain delicate, international matters differs much from that of my predecessor. We’ve been in this damnable war since 1914 and now we have some end in sight. The Americans are hot and heavy in the breach and they’re turning the tide. We need their guns and butter, so to speak, and our people especially need the butter.

“The American President, Mr. Wilson, is still a naif, as far as I’m concerned, and for all his sermonizing, he just doesn’t grasp the realities of geography nor the concept of empire.”

“Perhaps he does; all too well.”

Lloyd George looked at Holmes harshly.

“I don’t need your editorializing at this hour, nor at any other, Mr. Holmes...” Holmes cut him off.

“Then with all respect, Prime Minister, I need not a parochial Sunday school lesson on world politics.”

The Prime Minister’s expression changed to that of one who knows he’s in for a battle of wits, and who now fiercely suspects that he may be the loser.

“Quite. Then, Mr. Holmes, I shall come to the point. My government cannot upend the political or martial boat. Yet I, in all good conscience, cannot refuse my Sovereign his request without going to my end heaping calumny upon my soul. And there are others, invisible others, who share my sentiment entirely.

“However, there are those who would use the knowledge of this night to further some ulterior, republican motive. There are enemies who would use this against us in the arena of world and internal politics. And there are those, simply in opposition to my government, who would use this to try to oust me in the middle of this war.

“Mr. Holmes, we already have men in place in Russia; put there before the hostilities commenced in August 1914, put there before the century was born. These and others have supplied life’s blood information to our intelligence services, and a special, trusted few have matters in the ready.

“I cannot and will not tell you more at this juncture, only that you will be afforded every aid it is possible to provide. All that will become known to you as you need it.

“Now it is imperative that you leave as soon as possible, because you are going into Russia as an infinitesimal portion of a force of invasion.”

“An invasion? Ah, Archangel,” and Holmes waited smugly for the inevitable reaction of the Prime Minister.

“Good God, man! How did you know? Are there lips flapping like sails again in the Admiralty?”

“Calm yourself, Prime Minister. I have not obtained this information from some careless officer. On the contrary, all men in service whom I’ve met have been most circumspect.”

“But how then?”

“Sir, it is no geographical conundrum that once the English held Murmansk...” here Lloyd George instantly interrupted.

“At the Bolsheviks’ request, mind you. At their request.”

“Yes, of course; the logical port large and close enough to hold an invasion force would be Archangel. And since the civil war has been especially heavy in that unfortunate part of Russia, I should naturally suspect that the Allies would want to secure that area for themselves.”

“You mean to ensure neutrality, don’t you?”

Holmes’ eyes narrowed slightly, “Of course, by all means, neutrality.”

For the first time, Lloyd George seemed to actually exhale.

“You know, Mr. Holmes, I have often read of your exploits and unique deductive powers, but until this moment, I had no personal appreciation of them.”

“Ah, yes, well, this was merely one of the more simple paradoxes.”

“Really, well perhaps you might like to predict the outcome of the war, as well. I mean the precise outcome, since it is already evident that we shall win this war at any time now.”

“Prime Minister, the day the war began, I wrote the war’s virtual history, which I then sealed and placed in the care of Dr. Watson, with specific instructions that it not be opened until the war was over.”

“Did you, now? And what had you predicted?”

“Deduced, Prime Minister, deduced. And since I no longer have my history in my possession, and have given such specific instructions to Dr. Watson, I would rather not make mockery of my loyal friend’s diligence by despoiling my own dictum.”

It was clear to Holmes that he and Lloyd George were not getting on, at all. And as Holmes later said to me in the utmost of confidence, he had the distinct feeling that had he not been needed for this particular task so urgently, Lloyd George could easily have dispensed with him.

I asked Holmes what he meant by that remark, and looking straight and intently into my eyes, as if he were trying to physically send his answer to me through the sheer power of his will, he said, “Fair is foul and foul is fair: Hover through the fog and filthy air.”

Based upon the events that were to grimly unfold over the next several months, and furtive hints from Holmes along the way, I could not but help to wonder if Holmes in fact did have some premonition as to an undeserved end. That he had instantly grasped that fact upon speaking with the King: once his necessity was ended, he could, and must, be dispensed with.

The conversation continued between Holmes and Lloyd George.

“Very well, Mr. Holmes, keep your prognostications to yourself. While Rome burns, you fiddle. Have it as you will. But I hope I make myself clear: you and I have never met. You have never been here. The person with whom you spoke in the other room does not exist. Not even this room exists. This all could be nothing more than a cocaine-induced hallucination; something with which, I understand, you are more than familiar.”

Holmes bridled, but chose not to give the Prime Minister the satisfaction of a reaction.

The Prime Minister continued to bore into the wound.

“You will pack what you need and leave immediately. The two gentlemen who fetched you to me will see you safely home and then onto your place of embarkation. You will say nothing to anyone you should encounter until you are with those who will accompany you on this task. Do I make myself absolutely clear, Mr. Holmes?”

“As clear as your explanation during The Marconi Scandal,” said Holmes, referring to the scandal which led to an investigation in the House of Commons in 1913. A shady matter, indeed.

“But you now understand me. From the moment of illumination as to this task from the gentleman who does not exist, I comprehended completely its implications and I accept all save one: I shall need the assistance of one without whom, I fully believe this undertaking shall lead to failure.”

“And who may that be, pray tell?”

“Dr. Watson.”

“Dr. Watson? Your chronicler? Out of the question.”

Holmes smiled.

“To what does Dr. Watson owe this casual dismissal?”

“From what I have been told, your Dr. Watson is a mere tail of the dog,” Holmes’ smile faded slightly, “an errand boy with a minor literary talent for turning your aid to Scotland Yard into stories for the masses.”

“Given the circulation of The Strand Magazine, Prime Minister, I think it is clear that Dr Watson’s literary talent is a little more than that.”

Lloyd George was unmoved.

“Dr. Watson, as shall all of your intimates, remain innocent of this evening’s events.”

“On the contrary, Prime Minister, Dr. Watson shall accompany me or you shall be forced to seek aid elsewhere.”

“How dare you say this to me? How dare you?”

Lloyd George’s voice raised to such levels that Holmes’ two nannies burst into the room. Lloyd George waved them out vigorously.

“Who do you think you are, Mr. Holmes?”

“The man that you need.”

“Arrogance as well as disloyalty?”

“Disloyalty! You call me disloyal! Have I not already agreed to undertake this task knowing more than well the many dangers to my very existence? Disloyal, for demanding the aid of the one man whom I believe with all my being to be indispensable to the success of that task? Retract your words, sir, now, or I swear that I shall re-enter that room so that the gentleman who does not exist shall learn of your words.”

Lloyd George was in absolute, yet silent, fury. Holmes, ever equitable, reported that not only did Lloyd George fight to contain that fury quite admirably, but that as he did so, his boar’s bristle moustache stood so virtually on end that Holmes suspected he had been hiding tusks.

Finally Lloyd George calmed himself, sat in his chair, clasped his hands together on his desk, pointed at Holmes, yet did not look at him, and almost inaudibly asked, “Just why is this Dr. Watson so indispensable to you, Mr. Holmes?”

The smile had returned to Holmes’ face.

“Sir, I am a complex individual and take quite a time to be gotten used to. Not only has Dr. Watson succeeded in that unenviable task, but through the years and countless cases in which he has aided me, we have established a symbiosis of sorts that has become second nature to us both.

He has not only chronicled my cases, as you have stated, but he has been part of the very fabric of each and every one. He has provided succour when it was needed, a firm hand upon my psyche when called for, and unending trust through all. No man could ask for a better friend nor brother, for that is what he has become to me. Even my own blood, Mycroft, has not meant to me what Watson has.

“Further, Dr. Watson, as his title states, is a physician. And if memory serves, a particularly important member in this undertaking of mine has constant need of a physician, has he not? I believe he is a haemophiliac?”

“You have made your point, Mr. Holmes.”

Lloyd George looked at Holmes with all the bitter vengeance of the supplicant. Holmes sat opposite, his very proximity demanding a response from the P.M.

“Mr. Holmes, the more people who are involved in your task, the more opportunity for mistake. We cannot afford mistakes. We have had too many in recent years.”

“There shan’t be any on this occasion.”

“What guarantee have you?”

“Why I should have thought that quite plain, sir. My life.”

“That is no guarantee at all. You can be struck by a hansom cab crossing Piccadilly,” Lloyd George spat.

Was this a threat? A warning of some sort?

“Where I am off to, there are no hansom cabs.”

Lloyd George unclasped his hands, stood, crossed the room to the door and opened it. As Holmes rose and moved to leave, the Prime Minister took hold of his left arm.

“You shall have your Dr. Watson. But remember this: his fate is in your hands. Should you fail, the consequences will not only crush a certain person, but will most certainly, and quite literally, crush those who failed.”

Holmes pulled his arm free.

“And does that not include you, Prime Minister?”

“You forget, Mr. Holmes, this night never happened.”

And with that, Lloyd George shut his door and Holmes went back into the black morning; a reluctant charge still, of his two Neanderthal nannies.

At this point, Holmes was brought straight to my home where he proceeded to rouse the household with his pounding on my unfortunate front door.

I now knew all, or thought I did, and understood completely why we had to go into Russia. But what, I thought to myself, what will I ever tell Elizabeth?

And as if he had read my mind, Holmes said, “Leave Mrs. Watson to me, my friend. You shan’t have to dissemble on my account.”

Holmes suggested that he leave immediately to gather what clothing and equipment he would need from acquaintances in London who could help. This would give me time to begin my own packing. As for my wife, he would attend to her questions upon his return; which he felt, would be no more than a few hours hence.

With that all agreed, I accompanied Holmes to the door, and there, waiting next to the large, black motor car, I saw for the first time, the nannies of whom Holmes spoke. When Holmes walked down the stairs and paused for a moment at the vehicle’s side, I saw precisely how large they were.

Holmes got into the vehicle, with the larger of the two right behind. Although, I was not sure, I thought the smaller gave me a tiny, knowing nod, as if to say, “Don’t worry.” With that, he, too, hopped inside, and the motor car, still with its curtains drawn, sped off into a city receiving its first morning light.

We’re Off

In three hours Holmes was back, and he hadn’t been so excited or happy since his successful solution of the mystery I came to call “The Adventure of the Second Stain.”

Holmes was buoyant, and knowing full well the daunting task that lay ahead, I thought his actions incongruous, to say the least.

“What is it, Holmes,” I asked, “that makes you flit about so?

“I am merely smacking my lips at the challenges ahead and of how I shall overcome them.”

“But Holmes, our burdens are behemoth. They should weigh one down, not buoy one up.”

“No, no, Watson. The burdens, or challenges to which you refer, are quite separate from mine.”

I shook my head in absolute puzzlement at this newest, inscrutable Holmes remark. What challenge ahead could be separate from his? And it is only through time that I dare to suppose that what Holmes had been referring to was linked somehow to David Lloyd George. To some hidden, yet mutually understood, contest of the two. But what was it? Did it pertain to the unseemly words spoken at their clandestine meeting? Or was it something more visceral between the two?

You shall learn of this later; because even though I shall have to reveal to you what all this meant, and must do so in utmost sorrow, I have this compulsion to keep its meaning cryptic at this point in my journal, hoping that you shall unravel the meaning yourself, before it is divulged to you.

And should you wonder why this completely illogical compulsion on my part, perhaps it is some deep, inner longing to find in you, strong traces of me. No, that is not it. I long for you to find in yourself, Holmes. Such irrationality on the part of a physician, no doubt, comes as a shock. But I feel that you may need the test. Tests to which I found myself continually subjected by Holmes.

Holmes suggested that perhaps now was the proper time for him to speak with Mrs. Watson. I wholeheartedly agreed as I had, with tremendous difficulty, remained silent through her questioning, more thorough and sustained than any given by Mr. Sherlock Holmes and the whole of Scotland Yard combined.

Elizabeth and I had married in 1903. Holmes was later to complain that my absence had forced him to record his own account of the case he later entitled “The Blanched Soldier”. He did however admit that it had demonstrated to him that writing up his cases for a literary audience was harder than he had at first supposed.

Mrs. Watson was seated nervously in our solarium, waiting for Holmes, who repeated to me on our journey, verbatim he claimed, the extent of their conversation; although, I learned later that he had lied.

“Well, Mr. Holmes, after all this time, where are you dragging our John now?”

“Dragging, Mrs. Watson? Do you see a rope around Watson’s waist and I pulling maniacally at the other end?”

“Do not play your word games with me, Mr. Holmes, for we both love John, do we not?”

“That is so. And that is why I can tell you, with utmost truth, that I would perish myself rather than cause him even a scratch.”

“I know that, too, Mr. Holmes. There is no finer friend to John than you. Yet I feel that there is something very different about this particular matter. Just my feminine feeling if you will, but I am as certain of this as I am of the sun rising tomorrow morning.”

“Mrs. Watson, because of what your husband and I have been through together, much of which you have read or heard about, you know full well that there are sensitive things of which we may not speak.”

“I am fully aware of that, Mr. Holmes. But this matter, as I have said, seems eerily different and frighteningly dangerous.”

“Has Watson communicated to you any hint of danger?”

“Mr. Holmes, don’t be foolish. You know as well as I that John is as a sphinx where you are concerned. No, it is because of what he has not said that I fear so.”

“Then listen to this, please, madam. It is true, where Watson and I go there is more danger than he has faced since Afghanistan. But his service to his country in that awful place has been one of the shining points of his life. He bears his scars for England nobly. Remember this as well, young John is much to live for. By the way, where is he? I’ve not seen him about.”

“He is away for a visit with my parents in Yorkshire for the blooming of spring, one of my fondest memories of childhood; and something that John and I wish him to experience likewise each year. But please don’t change the subject, Mr. Holmes.”

“Mrs. Watson, your husband loves you and your son above all else in this world. But there are other husbands and fathers who are serving their nation at this time of travail who have not been as fortunate. Watson knows this. At the time when fate has finally chosen to ask a favour of him, he knows that he must grant it. He would not be who he is if he stayed behind. He would not be the man you love so devotedly. He would not be the brother I have taken by choice.”

“Then take him, Mr. Holmes. I place his soul and his safety in your hands. And I know that you will return him to me. And Mr. Holmes, God bless you. For through John, I have come to cherish you, as well.” With that, Elizabeth had embraced Holmes, probably causing him some discomfort, and bidden him send me to her.

I went to her more reluctantly than I had ever done anything before. Facing wild Afghanis seemed infinitely more inviting at the moment, and I approached her with some considerable hesitation.

“You wanted to see me, dear?”

“Yes, John, of course I want to see you. I want to see you every moment of every day. I want to see your eyes laugh when looking at John. I want to see the way they sadden when you cannot help some poor patient. I want to see you sleeping at night, in almost the same repose as your son. I want to see you silently smiling at me when we’re alone in the privacy of our night.

“But for a time, and I don’t know how long, I am resigned to not seeing you at all. I shall tell John that you and Mr. Holmes are off on another one of your famous adventures; I know that will please him as it always does. I shall tell myself that you are off on nothing more eventful than a carriage ride in the country. I shall lie to myself so that you shall not have to.

“I shall go to bed each night knowing for certain that you shall return to us in the morning. And arise each morning knowing for certain that you shall return to us that night.

“I love you, John. And I pray you return swiftly.”

My wife then kissed me more tenderly than I ever remembered, and with tears in our eyes, I turned to join the waiting Holmes, totally unaware that I would not see my wife and son again for over one year.

Harwich

Holmes’ nannies put my baggage into the motor car and we were on our way; the nannies in front with the driver, Holmes and I in the rear.

Since the nannies said nothing, I asked Holmes if they still possessed the power of speech, to which he laughed and nodded. Yet throughout our entire ride, for a period of close to three hours, not one word was exchanged between them and us. Indeed, they did not once turn their heads towards us nor towards each other.

Of course at this juncture I had absolutely no idea where we were headed, and after what I thought a reasonable lapse of time, inquired of Holmes just where he believed we were going.

“A most pertinent question, indeed, Watson; and if my bearings hold true, I believe we are headed for Harwich.”

Harwich, during the Great War, was a most important naval base, and since Holmes’ travel sense was as keen as ever, he gleaned that although Chatham, another naval base, lay closer, it lay southeast. Since we were aimed northeast, the only logical destination was Harwich, a distance of some seventy-nine miles.

I had never been to a naval station during the war, closeted as I was as a civilian in the heart of London, and I was immediately impressed with my first contact, smart sailors in full battle dress barring our entry at the gates.

They reacted sharply to the papers shown by the smaller nanny, and the sailor in charge pointed off towards the right as he and said nanny exchanged words I could not hear.

“It shan’t be long now, Watson. In a few moments we shall meet the intelligence officer who is to guide us to our ship and perhaps even impart some new information.”

Holmes was quite correct. For no more than four minutes evaporated before the motor car stopped in front of a small and evidently temporary building. The smaller nanny went inside, and after a few moments, reappeared and gestured us to join him.

As we went, I noticed sailors already taking charge of our baggage. The larger nanny stayed inside the vehicle, not glancing at us at all. Yet as Holmes and I passed the smaller one who indicated the room we were to enter, he spoke.

“Mr. Holmes, Dr. Watson, I have seen you both safely to your destination; those are the extent of my instructions. But,” and here he hesitated, “good luck, gentlemen, whatever your task.”

And with those unexpected words, he let the door close and joined his compatriot in the black vehicle which cautiously moved away from us, sinister no longer.

I looked at Holmes, “What do you make of that, Holmes?”

“Rather more than I expected, Watson,” said Holmes as he moved down the hallway and I followed hard behind.

As we walked on I was surprised to see a quite young officer, who, in these surroundings, looked wet behind the years. He advanced with an endearing smile to greet us.

“Why, Mr. Holmes,” his hand stiffly outstretched, “this is more than I had hoped for.”

“Ah, you give yourself away, Commander. You were told to expect a V.I.P., but you were not sufficiently entrusted with precisely who to expect.”

“Sir?” the officer was sandwiched between awe and evaluating a Holmesian deduction, and a coherent response appeared beyond him.

“And that, Watson,” Holmes said to me so that only I could hear, “means that we shall be passed between many links on our chain, each link unaware of the strengths or weaknesses of that adjoining; and perhaps not prepared for the chain to break.”

I was about to comment on that, but the officer was now holding out his hand to me.

“And this is Dr. Watson, Commander,” said Holmes.

“An equal pleasure, doctor, I’m sure.”

“Thank you, Commander,” I said. After the handshakes and smiles, our young officer asked us to sit.

“Forgive me, gentlemen, in my excitement it seems that I have omitted to introduce myself. I am Commander William Yardley, and I shall be your liaison at Harwich. I will escort you to your ship just before boarding,” he stared at the clock on his desk, “which should be only a very short time now, indeed.”

The young commander reminded me greatly of someone, and until Holmes and I exchanged that glance it hadn’t come to me. Then, immediately, it did. The commander looked like a young Holmes. I don’t know if Holmes noticed this, although there was not much that Holmes did not notice. But when it came to his own appearance and dress, Holmes seemed to be continually lost, or profoundly disinterested. And because of this resemblance, I felt very at ease with the young commander.

“Tell me, Commander,” said Holmes, “might you happen to know where Dr. Watson and I are going?”

“I’m afraid not, sir. That information, I suspect, is most secret. In any case, and I do not mean this in an ill way, it has nothing to do with me. My orders are to see to your comfort and security while you are at Harwich, and to see you both safely aboard the ship now making ready.”

“Commander, might you at least tell us its name?”

“Uh, I think so, sir. Yes, I do believe that would be within limits. You will be boarding HMS Attentive, a light cruiser. The captain is a splendid fellow; in fact, by coincidence, an old friend of the family. His name is David. Captain Joshua David.”

“Splendid, Commander,” said Holmes, “all those superlative biblical associations reassure me greatly.” We all laughed.

“Gentlemen, may I offer you some lunch, or perhaps a drink?” asked the commander.

I spoke up readily, since I had not eaten since a pre-dawn breakfast brought about by Holmes’ incessant excitement.

“Lunch would be welcome, Commander, very welcome.”

“And you, Mr. Holmes?”

“Don’t put yourself out on our behalf, Commander.”

“Of course he should, Holmes, that is what he is here for, remember?”

“No bother at all, Mr. Holmes. Of course the fare is most assuredly not what you may be used to, but we do nicely here, even with the war on.”

“Whatever is convenient, Commander,” said Holmes, as he lit a cigarette.

The commander stepped out for a moment and then rather unsettled, returned.

“Gentlemen,” said he, most unhappily, “I’ve just been informed that you are to report aboard the Attentive immediately. I’m sorry for the inconvenience and change of plans.”

“Nonsense, Commander, plans change, you know,” I said, remembering my own days on active service.

“Your bags have already been taken aboard, so if you’ll both just follow me.” He held open the door, followed us out into the hallway, and led the way towards our vessel.

Holmes’ eyes seemed to survey each square inch of the station as Commander Yardley escorted us. I chuckled to myself as multitudes of sailors scurried to every discernible compass point; each attending, no doubt, to a mission that would quickly end the war.

Presently we approached our vessel and the commander made it official with an envious sweep of his arms.

“Here she is, gentlemen, HMS Attentive. And I shan’t mislead you at all by confirming her as sweet and swift a vessel as I have ever encountered.”

The Commander then paused at the gangway and again extended his hand to Holmes.

“I know not what adventure you are off to now, Mr. Holmes, but I wish I was going with you. Good luck, sir.”

“Thank you, Commander. I hope we shall meet again when the war is over. But...” Holmes’ words trailed off as he began upwards.

“Watch after him, Dr. Watson. We need men like that in England.”

“Watch after him: Who’ll watch after me? Don’t we need men like me in England, as well?” Of course, I was just having sport of the officer, but by the dark look on his face, I instantly saw that I had truly wounded his sensitivities.

“No, Commander, I was only jesting,” I said.

“Thank you, sir. I meant nothing untoward, I assure you.”

“Nothing of the sort, lad. Good luck, Commander.”

We shook hands, and as I stopped for a moment’s look back in the midst of my climb, I saw the commander standing at attention, looking in our direction, and saluting. It was one of the most touching sights in my long memory.

Holmes and I were piped aboard in very fine style, shown to our quarters, which seemed cramped even for a small ship of war, found our baggage already there, and were then brought to the captain’s cabin where he was waiting to greet us.

“Ah, gentlemen, do come in and sit down. It is a great pleasure, Mr. Holmes,” he said, shaking Holmes’ hand with both of his own, “a singular honour, Dr. Watson,” and he then shook mine; but with only one hand. “I am Captain Joshua David.”

The captain was a man in his mid-fifties, I would say, not wanting more girth at this stage of life, with thick dark hair that I suspected he coloured. He moved about as would one walking on eggshells, with his hands clasped behind his back. Other than this entirely unique gait, I saw nothing extraordinary about him.

“Well,” said Holmes upon sitting, “I see that you were more informed than your young commander. He didn’t know who to expect.”

“Really? I wasn’t aware that you were not brought directly to me. Which young commander are you speaking of? We have a surfeit of young commanders these days, you know. Were you inconvenienced in any way?”

“Not at all,” I said, “it’s just that we were about to partake of a light luncheon when we were summoned.”

“Oh, I do beg your pardon. I shall see to your comfort post haste.” He then ordered his steward to have luncheon brought up to his cabin.

“The Commander’s name is Yardley, Captain. William Yardley.”

The captain took on the typical “rub the chin, scratch the head” gestures of someone trying to appear in the act of taxing his brain.

“Yardley...Yardley, no, not familiar, at all,” said the captain.

“But,” and before I could say one syllable more, Holmes had jumped into the conversation.

“It is of no consequence, Captain. Tell me, if you will though,” Holmes had risen and walked to a large map on the far wall of the cabin, “where are we bound? This map should show our destination.”

“And that it does, Mr. Holmes. But until I receive orders, I’m afraid that I am as much a part of this mystery as are the both of you.”

“You mean that you shall receive your final orders at sea?”

“That is exactly what I mean, Mr. Holmes.”

“Well, then, can you tell us when we are to sail?”

“I can and I shall. We shall be underway presently. If we are not clear of Harwich within the half-hour, I will be very much surprised.”

Lunch was brought to us, tepid in flavour as well as in temperature, but I was happy regardless and ate heartily. Holmes spoke little during the meal, so I regaled our nautical host with tales of the army; perhaps not the most intelligent of subjects to choose while in the power of the navy; but, we were all fighting the same war, were we not?

Once back in our quarters, Holmes checked the corridor to see if there was anyone about. When he was sure there was not, he sat, and I could see his mind adding, subtracting, dividing and sorting information at a furious rate.

“Well, Watson, what make you of all this?”

“Do you mean about David supposedly not knowing Yardley?”

“Or is it Yardley supposedly knowing David? Yes, that’s part of it. But even before that, did you find anything curious about Harwich?”

“How do you mean?”

“Remember that we were supposed to be part of an invasion force? To Archangel?”

“Yes, and it seems that we are, with all these ships. Are we not?”

“Not in the slightest, Watson. First of all, if this were the staging point for an important invasion force, tell me this: how many soldiers did you see?”

“Soldiers? Why, of course,” embarrassment had no greater offspring at that moment.

“Precisely. There weren’t any. It was all naval personnel at Harwich. Not one troop ship. And I don’t seem to recall a successful invasion without an army with which to invade. Furthermore, since when in all of British naval history, has its captains set forth on some great undertaking without specific instructions as to where and when? It knots my mind, Watson, to think them so contemptuous of my powers that I would believe this Captain David!”

“I don’t understand, Holmes. Lloyd George told you himself of this invasion, did he not?”

“No, I told him. He only play-acted; brilliantly, too. Making me believe that I had deduced some deep military secret.”

“I still am not following.”

“Watson, you and I both know what our task is in Russia. But what if we are the only two, besides Lloyd George and his minute, inner circle of invisible others, who know it?”

“You’ve completely lost me now, Holmes.”

“I am saying this: what if each of the links I had mentioned to you onshore, is not only unaware of each other, but unaware of what our goal is, as well? If they have been given only enough instructions, as say, to take us from A to B and no more, then who is to say what we are really about? For all intents and purposes, we could be on a secret mission to gather pollen!

“Watson, it is quite obvious by now that Lloyd George has led me as a trainer leads a reluctant thoroughbred into an unwelcome arena. Is it not then also possible that he has obfuscated completely? And if that is the case, then anything is possible - absolutely anything.”

“But what about His Majesty, Holmes? Did not the King himself say that he had chosen you for this enterprise?”

“Indeed. And that is one part of this puzzle that does not fit.”

“Well, if we are not headed for Russia, Holmes, where are we headed?”

“I still believe that we are being led to attempt the successful completion of our task. And if that is so, then we must still be headed for Russia. Indeed, most certainly then for Kronstadt.”

“Kronstadt?”

“Yes, it is the naval base nearest St. Petersburg, approximately forty miles. It guards the way to the capital. If the Bolsheviks were politically practiced enough to invite such unwelcome guests as the English into Murmansk, to guard the capital from flank assault by the Germans and Finns, I am willing to wager there is another game afoot in Petersburg. A much more intricate game than I was led to believe I would be playing.

“I thought it a simple question of Red or White, rather like which wine to choose for dinner, but this is deep, Watson, deep. As yet I cannot fathom the intent, but whatever it may be, I believe that for our direct entry into Kronstadt, the waters will be made calm. And should the German navy act as spoiler, it makes it the more interesting.”

With that, Holmes lay himself down in his bunk; and for the first time in what appeared to be two days or more, he slept. I, in no shallow attempt at imitation, did likewise.

When next I awakened, some four hours later, I found that we were long into the North Sea, indeed far from Harwich, but only slightly closer to the solution for which Holmes was searching.

Later that evening at dinner in the officers’ mess, we met the ship’s elite. The officers had been briefed that we were special envoys to the new government in St. Petersburg, summoned at their request, to help them recover invaluable Romanov jewellery, which, when sold to rich capitalists, would be used to benefit the Russian people.

Throughout the meal Holmes said little, so intently was he dissecting Captain David. After but one sip of brandy at dinner’s completion, David rose and began his arresting walk around the table.

“I trust you slept well, Dr. Watson?”

“To be perfectly honest, Captain, I would have napped well even perched atop the Great Pyramid.” This brought laughter from all.

“I take it then that you are not fond of our arrangements?”

“Not so. It’s just that I am a landlubber, many generations bred, and my body was greatly confused by an unsuspected turmoil, when it is used to terrain remaining stationary and happy to be so.” More, and heartier laughter ensued.

The captain waited for the laughter to dissipate, and then, with great earnest, he addressed us all.

“Mr. Holmes, Dr. Watson, men, I understand that many of you have taken to guessing about our destination based upon the headings I ordered. Well, you can stop your calculations as I tell you what that destination is.”

With all men, including myself and Holmes, physically bent forward, as you would expect from a crowd at a close horse race, the captain proceeded to pull down a large map of Europe; and then commenced his briefing in the style of a geography tutor.

“Men, as to our direction, Bremerhaven is portside. In about eleven hours time we shall be passing Jutland,” at the mention of which, the men tapped the table, “then up and around Skaggerak, down through Kattegat Channel hard by Laesö Island, then down through Oresund, taking us into close enough proximity to Kiel to perhaps have the Huns salivating in wait. However, should we still be afloat, we then proceed northeast through the Baltic to Kronstadt.”

Subdued comments from the officers indicated that they expected and hoped for some action.

I looked at Holmes as I always did when one of his theories had been proved true, but Holmes was studying the map.

“Pardon me, captain,” I interrupted, “but what, precisely is the importance of Laesö Island?”

“Come Dr. Watson, do you mean that an old military man such as yourself is unfamiliar with that island?”

“Captain,” I retorted, “I should like you to find the position of the Isles of Langerhans on your first autopsy!”

“Enough, sir,” laughed the captain, “show mercy and I shall haul down my flag.”

“Granted, captain,” I said, “but in all seriousness, what truly is the significance of Laesö Island?”

The laughter was gone now as Captain David, with the composure of command, slowly looked around the room till he came again to me.

“It means simply this: that we are forced to penetrate the neutral waters of both Denmark and Sweden in an attempt to evade any confrontation with the enemy. And that in waters so narrow, there is no way of knowing if we shall be successful.”

“Sir,” it was Lt. Leicester, perhaps the youngest of the officers present, “do you think we shall be engaged?”

“Well, Lieutenant, according to Newsome, the enemy should be all over the place. Both on the surface and under. If you ask me, they should be called ‘rat packs’ instead of ‘wolf packs.’”

At this, the men laughed and concurred.

I studied the faces of all the officers, and to a man, they were now sullenly pensive.

Holmes shot up as if propelled by a giant spring.

“Captain, gentlemen, thank you for a meal of such illumination. If we may, I believe that Dr. Watson would like to join me in a stroll around your deck.”

“Well, Mr. Holmes, this is not a pleasure ship with decks for promenade, but on a night as beautiful as this, I believe that the rules of war will not be irreparably broken if you have your stroll.”

“Thank you, Captain, gentlemen”, he gestured for me to rise and do likewise.

“Indeed. Captain, gentlemen.”

The officers wished us good evening, Holmes and I left them there, now gathered at the map, and proceeded down to the deck.

“Well, Holmes, what was it that shot you from an invisible cannon?”

“Newsome, Watson, Newsome.”

“Yes...?”

“A name thrown out so casually suggests frequent and informal conversations. In other words, a long acquaintance or friendship.”

“So what great import does this Newsome hold for us?”

“Not only for us, Watson, but for all of England. For I heavily suspect that the Newsome to whom Captain David so innocently referred, is none other than Sir Randolph Newsome, the Deputy Director of Naval Intelligence.

“And since when does a Deputy Director of Naval Intelligence personally inform a mere captain of a cruiser, and a light one at that, about the chances of hostile encounter; especially when that data is usually laid out by some junior statistical actuary.”

“I see. So you suspect that Newsome is in on it.”

“Perhaps yes, perhaps no. One thing I do know, this ship is, supposedly, assigned to the singular task of delivering us to Kronstadt in one piece. And not even persons high in government, including prime ministers, can play loose with such a prize as this vessel in time of war.

“No, Watson, it seems as if we are being given every opportunity to rescue the Russian family. But I, like a donkey, must perform with a carrot continuously held in front of my eyes.”

With that remark, Holmes turned away from me and disappeared into the black that enveloped the ship’s bow.

I succoured myself with sleep, but was so suddenly and violently awakened that I smashed my head into the rear wall of my bunk. After rubbing vigorously, I noticed that Holmes was absent.

I became aware of a bleating sound and immediately understood its meaning. After jumping into trousers and grabbing my coat and life vest, I opened the door to find sailors running right and left as if bereft of direction.

As I stepped out into this madness, a tow-headed sailor came running up to me.

“Dr. Watson, you are to follow me, sir!”

“Lead on,” I said and he started off. In fact he did so with so much coltish proficiency that he had to stop briefly twice to be sure I was still behind.

Upon reaching our battle stations, I was told that a periscope had been seen and that we were to stand to. Still no Holmes.

As I waited there virtually motionless, with everyone else in perpetual motion around me, I asked myself, for the first time on this journey, just what was I doing here?

Out of the fog, I heard Holmes saying behind me, “Lovely night for a swim, eh, Watson?”

“Very amusing, I’m sure, Holmes. Why didn’t you awaken me when you bolted from our cabin?”

“Come, come, Watson, you should know me better than that. I wasn’t even in our cabin when this ruckus began.”

“I suspected as much. Where were you?”

“Enjoying this beautiful night, Watson. Enjoying this beautiful night.”

“Well, it shan’t stay beautiful if we’re dumped into the sea.”

“I strongly doubt that, my dear fellow. After all, that is what life boats are for. Anyway, all we can do is hold onto this rail and wait.”

And wait we did. After a few moments, all seemed as silent as a sepulchre. The sailors were all at their stations, heads moving in every direction, eyes trying desperately in the dark to make out an enemy movement or shape.

I sweated in spite of the crisp North Sea air, and was happy to see the same dew on the foreheads and faces of those in close proximity.

Suddenly the ship lurched up with an awful roll to starboard that rent me free of my grasp of the rail. It was Holmes who grabbed me as I began to fall past.

“I’ve got you, Watson.”

“Thank you. Were we hit?”

“I don’t think so, there wasn’t any explosion. I think it was just a sharp, evasive move.”

We then waited for what seemed some considerable time, but nothing more happened. Finally, the all-clear was sounded and Holmes and I permitted ourselves to exhale. Nervous laughter followed, mixed with quiet verbal exchanges and the omnipresent gesture of crossing the body.

Holmes and I, while making our way back to our cabin, passed young Lt. Leicester.

“Well,” he said with a big, boyish smile, “you certainly can’t fault us for not providing after-dinner entertainment.”

We bade him good night again, fell into our bunks fully clothed, and this time, slept uninterrupted.

June 14, 1918

Upon waking next morning, mid-morning, in reality, I once again found Holmes missing. It never ceased to amaze me how little sleep Holmes required. As a medical man I had read case histories where people required as little as twenty minutes of sleep a night. I required the usual dose in order to function.

I renewed my practice of dressing and shaving with the seductive sway of a ship, and after a few, literally close shaves, my hand and eye became adjusted to the yaw. I believe I performed admirably; as well, perhaps, as if I had a scalpel in hand during an operation, in the midst of a bitter engagement with some wild Afghani hill tribe.

I made my way back up to the officer’s mess where I partook of a very late breakfast and was informed that the action of the night preceding had been nothing more than a false alarm, and that we would shortly be passing Jutland.

I went topside and saw Holmes at starboard, looking, I surmised, in the direction of that hallowed place of battle. But before I could walk to him, I again chanced upon Lt. Leicester.

“So, Dr. Watson, I hope things are going well for you?”

“Yes, quite. Thank you.”

We had reached Holmes by this time, and after hearty good mornings all around, Lt. Leicester took on a mock, conspiratorial tone.

“Gentlemen, you should feel honoured.”

“Honoured?” Holmes asked. “How so?”

“Well, that was quite a show the old man put on for us last night. I guess he was just trying to impress us, him being new to the ship, and all.”

“New to the ship, you say?”

“Why yes, Mr. Holmes. Capt. David only joined us about five days ago. Our regular skipper, Capt. Stanley, was promoted to a staff job of some sort at the Admiralty. And you won’t blame me for saying that the crew still miss him quite a bit.

“This new captain is an all right sort, I guess, but we can’t seem to find out too much about the man. Only that he was supposed to have been in at Jutland commanding another light cruiser, the HMS Pegasus. And that’s the strange part about this. You see, I have a good friend who was an officer aboard a destroyer there, and he seems to remember that the Pegasus had been commanded by a Capt. Bartholomew.

“Oh, well, I guess it’s all just some misunderstanding. Anyway, I must be off before the crew mutinies. I hope to see you later.”

He saluted smartly and strode briskly away, a young man happy with his calling, proud of his ability, and looking forward to the future.

“Well, Watson, whether or not our good captain commanded the Pegasus, he’s certainly an old sea dog from his ease of command and demeanour around the ship. But I do not think at this stage we shall accomplish an unmasking. Capt. David is now confirmed as merely the second link, although a much more important and formidable link than the first.”

Within the hour, we were passing Jutland, rather larger than I had anticipated, and Holmes and I watched quietly as the officers and men came to a brief attention and then saluted.

Three days later, we were through the Oresund Narrows, and were about to enter decidedly German waters.

Battle

It was exactly eleven-seventeen A.M. when Holmes and I, and the men of Attentive, saw that which we secretly wished never to see: an enemy ship. A very large enemy ship.

Battle positions were sounded and we were told later that the German ship was a prowling destroyer; by no means the most potent warship in the enemy’s arsenal, but potent enough for a peaceable doctor. Holmes and I were sent below.

I think that Holmes and I both shared the same feeling during the brief engagement: impotence. We could not fight back. We could not contribute martially. But I could contribute as a doctor and Holmes, with his knowledge of human anatomy, could certainly help. From what we were told after the battle, this is what happened.

Our crew saw them before they saw us. Our captain immediately called all to battle positions and made ready for a run, knowing that we could not possibly out gun a destroyer. Not only did the Germans have ten-inch guns to our sixes, but the Attentive, like all her sister light cruisers, was built for speed and scouting, for escort and raid. Therefore, she was more lightly armoured and armed than our larger and more predatory ships of the line. So Capt. David was counting on speed and luck. He received both in moderate measure.

We were about ten miles distant when the Germans fired their first shots. They missed and our men gave a loud cheer.

But some of their second salvo found their mark and we were hit amidships. The two-hundred-pound high-explosive shell landed amongst the ready-use lockers of the rockets, causing those already loaded to explode. And from this one direct hit, all our casualties sprung, for there were no more hits. We managed to outrun the Germans who gave up the shelling only after night; though our ship burned and glowed in that night like a beacon.

There was fire and smoke throughout amidships and scalding debris hailing down thick and fast. As misfortune would have it, Holmes and I were below the explosion and saw much horror at first hand.

Sailors turned into torches of pitch. Limbs severed or torn by massive steel splinters shooting about like arrows. Terrible cries for help lost amongst even more terrible cries. And the stench of roasting human flesh everywhere.

After the fires had been brought under control and it seemed as if there were no more wounded for us to treat, Holmes and I began a terrible tour around decks. After a short while, we came across young Lt. Leicester.

He was sitting upright against a wall, waiting for his turn to be treated by the doctors. Only his head was bandaged, and I could make out no other injuries. I looked into his eyes to determine pupil dilation when he recognized me.

“You see, Dr. Watson, we always provide entertainment.”

And with that, he ceased living. I tried to revive him, but Holmes knew it was hopeless; and after a sufficient time, Holmes gently steered me away, back to our cabin, back from the hell we had just shared with five hundred men.

It was now the stillest part of night. But on that ship, we were part of nature no longer. We had just journeyed through a dimension known only to demons, and many of us would not come back easily.

But HMS Atttentive proved, as Commander Yardley had said, sweet and swift, and the crew were British through and through. Damage was controlled and repaired, our speed was maintained, and we sailed quickly on. And as Holmes had said, whoever Capt. David was, he was truly an old sea dog.

Towards evening, all hands turned out for the solemn burial at sea. Sixteen souls sailed downward; and as each released from its Union Jack slipped away, I wondered which was Lt. Leicester.

We were now well into the Baltic, nearer the end of our journey than the beginning, and I pondered mightily on just who and what awaited us in Russia.

June 18, 1918

This day passed, thankfully, with nothing to jar routine. The wounded men rested and healed, but the wounded ship did not rest. It pushed onward.

June 19, 1918 Kronstadt

The captain sent for us this morning and told us to prepare. We would be on the island-base of Kronstadt before the end of day - if all went well.

We made ready, the Attentive arrived late afternoon, and by early evening, the captain came on deck to see us off.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “your trip has not been a happy one. I wish you better fortune here.”

We thanked him and then Holmes said, “Captain David, you have shown us your worth and wits in battle. It is we who wish you good fortune on your journey home.”

“Ah, yes. Well, we shall be here for a while for more permanent repair, then we must be home rather quickly. I greatly suspect that Kaiser Willy will try to make our voyage home even more eventful. There is more to this business, you know.”

He saluted as we went aboard the packet boat, and as we chugged into Kronstadt, Holmes and I saw what was left of the Russian North Fleet; battered so harshly by German guns and seamanship. Searchlights only served to heighten the damp air of death and doom that clung so tenaciously to that melancholy place.

Since March 3rd, when the treaty of Brest-Litovsk had been signed and took the Russians actively out of the war, a kind of limbo had engulfed all here, men and ships alike. They were thrust into a very personal purgatory.

As we neared the dock, Holmes and I focused on a large, black motor car with what looked like a military escort in front and behind. It was flying red flags of revolution.

As we stepped ashore, a Russian soldier opened a rear door for his officer who emerged and then strolled casually towards us. He stopped quite close, looked intently at both of our faces, took a deep breath and then, in a perfect English accent, said, “Welcome, comrades, I am Colonel Relinsky.”

Reilly

Relinsky, as we found out later, was Sidney Reilly, about forty, wiry, with a chiselled face as hard as that of a statue, and eyes of such sharp intelligence, that, as Holmes told me later, he immediately sensed an intellect of the first order.

When Reilly removed his cap in the auto, he revealed coal black hair combed severely straight back; an indication of how this man kept his own persona so rigidly in check. And though, at the time, neither Holmes nor I had any idea of who this man really was, I found out much later how singularly important he was not only to our task and to Britain - but to the entire Allied cause.

In fact, in the complete history of my human contact, Sidney Reilly ranks as the only man who I truly believe was as extraordinary as Sherlock Holmes.

There were, however, many differences: while Holmes was brought up on the inside of society, Reilly was shunted to the outside (he had been born in Russia, the son of an Irish sea captain and a Russian woman of Odessa); Holmes, though born with a superlative mind, cultivated it through learning and books until he had gained more practical experience, while Reilly it seems, almost from the beginning, was thrust into enough practical experiences to last many lifetimes; Holmes used his knowledge and powers solely for good and aid to his fellow man, while Reilly used his, including a startling fluency in seven languages, complete with sub-dialects, not entirely for the betterment of his adopted country of England, but most certainly for the betterment of Sidney Reilly.

Yet he was so important an asset to Britain and the Allies that he could virtually name his price. Permit me to give you just three instances of the powers and incomparable exploits of this man Reilly, as I would learn later.

First, before the war, the Admiralty needed knowledge of Germany’s submarine construction plans. It was Reilly who conceived of the method to obtain these plans completely shunning the usual cloak and dagger. He simply secured the post of naval armaments purchasing agent for a very important Russian boat-building firm. As such, he was feted at the Hamburg shipyards by the company of Bluhm and Voss, who, wanting to secure a rich, Russian contract, willingly gave Reilly all the plans England sought.

The second instance found Reilly entering Germany through Switzerland at the height of the war in 1916, gaining entry to the German Imperial Admiralty by posing as a naval officer, and making off with the entire German Naval Intelligence Code.

The third, and most incredible instance, involved Reilly being put into revolutionary Russia by the British. Reilly became Comrade Relinsky of the Cheka, heirs to the Tsar’s Okhrana, the secret police, and rose so high so quickly, that an organized plot of his almost put him into supreme power. Lenin would have been dispensed with.

Such were the abilities of the man who now stood before us and continued his address.

“We heard of your near miss. I hope you weren’t scathed.”

“Only our souls,” I said.