1

The ‘Alabama Insert’

A Study in Ignorance and Dishonesty

Richard Dawkins was invited in 1996 to present one of the lectures in the annual series now known as the Littleton-Franklin Lectures in Science & Humanities at Auburn University. During his visit, Professor Dawkins learned of the “Alabama Insert” and put aside his prepared text, choosing instead to deconstruct the statement by the Alabama State Board of Education. He gave permission for a transcript of his remarks and accompanying illustrations (by Lalla Ward) to be used to further evolution education in Alabama, and the lecture was published in 1997 in the Journal of the Alabama Academy of Science 68(1): 1–19. The “Alabama Insert” underwent slight revision in 2001, but because Professor Dawkins’s critique of the 1995 version of the “Insert” addresses so many current misconceptions about the theory of evolution, it is republished here with permission of the journal’s editor.

As a former prime minister of my country, Neville Chamberlain once said: “I have here a piece of paper.” It says “A message from the Alabama State Board of Education.” This is a flier that is designed to be—ordered to be—stuck into the front of every textbook of biology used in the public schools. What I thought I would do, with your permission, is to depart from the prepared text I brought with me. Instead I should like to go through every sentence of this document, one by one.

“This textbook discusses evolution, a controversial theory that some scientists present as a scientific explanation for the origin of living things such as plants, animals and humans.”

This is dishonest. The use of “some scientists” suggests the existence of a substantial number of respectable scientists who do not accept evolution. In fact, the proportion of qualified scientists who do not accept evolution is tiny. A few so-called “creation scientists” are much touted as possessing PhDs, but it does not do to look too carefully where they got their PhDs from nor the subjects they got them in. They are, I think, never in relevant subjects. They are in subjects perfectly respectable in themselves, like marine engineering or chemical engineering, which have nothing to do with the matter at hand.

“No one was present when life first appeared on Earth.”

Well, that is true.

“Therefore, any statement about life’s origins should be considered as theory, not fact.”

That’s also true but the word theory is being used in a misleading way. Philosophers of science use the word theory for pieces of knowledge that anybody else would call fact, as well as for ideas that are little more than a hunch. It is strictly only a theory that the Earth goes around the sun. It is a theory but it’s a theory supported by all the evidence. A fact is a theory that is supported by all the evidence. What this is playing upon is the ordinary language meaning of theory which implies something really pretty dubious or which at least will need a lot more evidence one way or another.

For example, nobody knows why the dinosaurs went extinct and there are various theories of it which are interesting and for which we hope to get evidence in the future. There’s a theory that a meteorite or comet hit the Earth and indirectly caused the death of the dinosaurs. There’s a theory that the dinosaurs were killed by competition from mammals. There’s a theory that they were killed by viruses. There are various other theories and it is a genuinely open question which (at the time of speaking) we need more evidence to decide. That is also true of the origin of life, but it is not the case with the theory of evolution itself. Evolution is as true as the theory that the world goes around the sun.

While talking about the theories of the dinosaurs I want to make a little aside. You will sometimes see maps of the world in which the places where people speak different languages are shaded. So, you’ll say, “English is spoken here,” “Russian is spoken there,” “French is spoken here,” etc. And that’s fine; that’s exactly what you would expect because people speak the language of their parents.

But imagine how ridiculous it would be if you could construct a similar map for theories of, say, how the dinosaurs went extinct. Over here they all believe in the meteorite theory. Over on that continent they all believe the virus theory, down here they all believe the dinosaurs were driven extinct by the mammals. But if you think about it that’s more or less exactly the situation with the world’s religions.

We are all brought up with the religion of our parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents and by golly that just happens to be the one true religion. Isn’t that remarkable! Creation myths themselves are numerous and varied. The creation myth that happens to be being taught to the children of Alabama is the Jewish creation myth which in turn was taken over from Babylonian creation myths and was first written down not very long ago when the Jews were in captivity. There’s a tribe in West Africa that believes that the world was created from the excrement of ants. The Hindus, I am told, believe that the world was created in a cosmic butter churn. No doubt every tribe and every valley of New Guinea has its own origin myth. There is absolutely nothing special about the Jewish origin myth, which is the one we happen to have in the Christian world.

Moving on in the “Alabama Insert,” as I shall call it:

“The word ‘evolution’ may refer to many types of changes. Evolution describes changes that occur within a species (white moths, for example, may “evolve” into gray moths). This process is called microevolution which can be observed and described as fact. Evolution may also refer to changes of one living thing into another such as reptiles changing into birds. This process called macroevolution has never been observed and should be considered a theory.”

The distinction between microevolution and macroevolution is becoming a favorite one for creationists. Actually, it’s no big deal. Macroevolution is nothing more than microevolution stretched out over a much greater time span.

The moth being referred to, I presume, is the famous peppered moth, Biston betularia, studied in England by my late colleague Bernard Kettlewell. There is a famous story about how, in the Industrial Revolution when the trees went black from pollution, the peppered pale-colored version of this moth was eaten by birds because it was conspicuous against the black tree trunks. After the Industrial Revolution years, the black moths became by far the majority in industrial areas of England. But if you go into country areas where there is no pollution, the original peppered variety is still in a majority. I presume that’s what the document is referring to.

The point about that story is that it’s one of the few examples we know of genuine natural selection in action. We are not normally privileged to see natural selection in action because we don’t live long enough. The Industrial Revolution, however unfortunate it may have been in other respects, did have the fortunate byproduct of changing the environment in such a way that you could study natural selection.

To study other examples of natural selection I recommend the book The Beak of the Finch by J. Weiner. He is describing the work of Peter and Rosemary Grant on the Galapagos finches. Those finches, perhaps more than any other animal, inspired Charles Darwin himself. What the Grants have done studying Galapagos Island finches is actually to sample populations from year to year and show that climatic changes have immediate and dramatic effects on the population ratios of various physical structures such as beak sizes.

Darwin was inspired by the example of the Galapagos finches; he was also inspired by the examples of domestication.

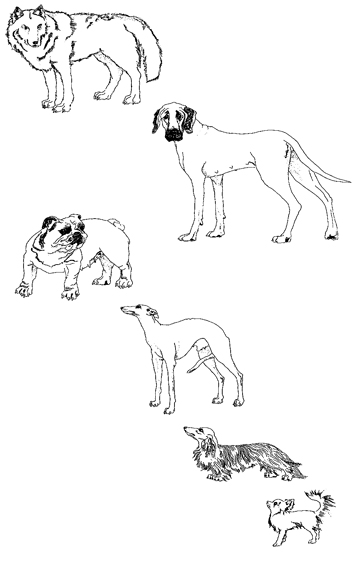

Figure 1.1 - The power of artificial selection to shape animals. All these domestic dogs have been bred by humans from the same wild ancestor, a wolf (top): Great Dane, English bulldog, whippet, long-haired dachshund and long-haired chihuahua.

These are all domestic dogs [see Figure 1.1] except the top one which is a wolf. The point of it is, as observed by Darwin, how remarkable that we could go by human artificial selection from a wolf ancestor to all these breeds—a Great Dane, a bulldog, a whippet, etc. They were all produced by a process analogous to natural selection—artificial selection. Humans did the choosing, whereas in natural selection, as you know, it is nature that does the choosing. Nature selects the ones that survive and are good at reproducing, to leave their genes behind. With artificial selection, humans do the choosing of which dogs should breed and with whom they should mate.

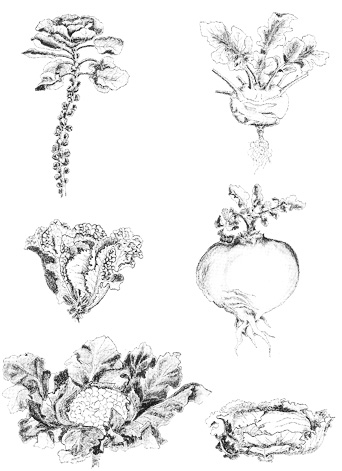

Figure 1.2 - All these vegetables have been bred from the same ancestor, the wild cabbage, Brassica olearacea: (clockwise from top left) Brussels sprout, kohlrabi, Swedish turnip, drumhead cabbage, cauliflower and golden savoy.

These plants [see Figure 1.2] are all members of the same species. They are all descended quite recently from the wild cabbage Brassica olearacea and they are very different—cauliflower, brussels sprouts, kale, broccoli, etc. This great variety of vegetables, which look completely different, has been shaped—they have been sculpted—by the process of artificial selection from the same common ancestor.

That’s an example of what can be achieved in a few centuries when the selection is powerful enough. When the selection goes on for thousands of centuries the change is going to be correspondingly greater—that’s macroevolution. It’s just microevolution going on for a long time.

It’s difficult for the human mind to grasp how much time geology allows us, so various picturesque metaphors have been developed. The one I like is as follows: I stand with my arm outstretched and the distance from the center of my tie to my fingers represents the total time available since life began. That’s about 4,000 million years. Out to about my shoulder we still get nothing but bacteria. At my elbow you might be starting to get slightly more complicated cells—eukaryotic cells—but still single cells. About mid-forearm you start getting multicellular organisms, animals you can see without a microscope. At my palm you would get the dinosaurs. Somewhere toward the end of my finger you would get the mammals. At the beginning of my nail you would get early humans. And the whole of history—all of documented written human history, all the Babylonians, Biblical history, Egyptians, the Chinese, the whole of recorded history would fall as the dust from a nail file across the tip of my furthest finger.

This is hard for the human brain to grasp, time spans of that order. Remember that the time represented by the dust from the nail includes the time it took these cabbage varieties to evolve by artificial selection (human selection) and dogs to evolve from wolves. Just think how much change could be achieved by natural selection during the thousands of millions of years before recorded history.

To reinforce that point there was a theoretical calculation made by the great American botanical evolutionist, Ledyard Stebbins. He wanted to calculate theoretically how long it would take to evolve from a tiny mouse-sized animal (ancestor) to a descendant animal the size of an elephant. So what we are talking about is a selection pressure for increased size. Selection pressure means that in any generation slightly larger than average individuals have a slight advantage. They are slightly more likely to survive for whatever reason, slightly more likely to reproduce. Stebbins needed a number to represent that selection pressure, a way to show how strong to assume it to be. He decided to assume it (the pressure) to be so weak that you couldn’t actually detect it if you were doing a field study out there trapping mice.

So Stebbins assumed his theoretical selection pressure to be so weak that it is undetectable; it vanishes in the sampling error of an ordinary research study. Nevertheless it’s there. How long would it take under this small but relentless pressure for these mouse-like animals to grow and grow over the generations until they became the size of an elephant? He concluded that it would take about 20,000 generations. Well, mouse generations would be several in a year, elephant generations would take several years. Let’s compromise and assume one year per generation. Even at five years per generation, that’s not many years, say 100,000 years at the most. Well, 100,000 years is too short to be detected on the geological time scale for most of geologic history.

For most characteristics a selection pressure as weak as that, so weak that you couldn’t even measure it, is sufficiently strong as to propel evolution so fast that it appears to be instantaneous on the geological time scale. In practice it probably isn’t even as fast as that, but geological time is so vast that there is plenty of time for the evolution of all of life to have happened.

Another theoretical calculation was made by the Swedish biologist, Dan Nilsson. He took up the question which Darwin himself was interested in—the eye, the famous eye, the darling of creationist literature. Darwin himself recognized the eye as a difficult case because it is very complicated. Many people have thought, wrongly, that the eye is a difficult problem for evolutionists because—“Doesn’t it have to be all there with all the bits working for the thing to work?”

No. Of course they don’t all have to be there. An animal that has half an eye can see half as well as an animal with a whole eye. An animal with a quarter eye has a quarter vision. An animal with 1⁄100 eye has 1⁄100 quality vision. It’s not quite as simple as that. The point 1 am making is that you can be aided in your survival by every little tiny increment in quality of eyesight. If you have 1⁄100 quality eyesight, you can’t see an image but you can see light and that might be useful. The animal might be able to tell which direction the light is coming from or which direction a shadow is coming from which could portend a predator. There are all sorts of things you could do that help you to survive if you have a small fraction of an eye, to survive better than an animal which has no eye at all. With 1⁄100 of an eye you can just about survive. With 2⁄100 of an eye you can survive a little better. There is a slow, gradual ramp of increasing probability of surviving as the eye gradually gets better.

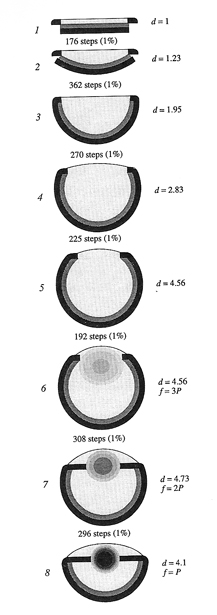

Figure 1.3 - Nilsson and Pelger’s theoretical evolutionary series leading to a ‘fish’ eye. The number of steps between stages assumes, arbitrarily, that each step represents a 1 percent change in magnitude of something. See text for translation from these arbitrary units into numbers of generations of evolution.

Going back to the question of the rate at which all this happens, Nilsson did a computer modeling exercise of the evolution of the eye [see Figure 1.3]. He starts from a computer model which is not really eye shaped at all but is just a flat sheet of light sensitive cells. You’ve got to start somewhere. You could start before that if you wanted to, but that’s where he started. He made the computer gradually change the shapes of this model eye. The only rule was that the changes had to be small and each change had to result in an improvement in vision. The beautiful thing about the eye is that by using the actual rules of physics, the ordinary rules of optics, you can calculate how good each of the hypothetical intermediates would be at forming an image.

These intermediates all formed spontaneously in the computer as a result of gradual improvement in what the computer could measure as the optical quality of the model eye, and it goes all the way from a flat sheet of cells to a proper camera eye with a lens such as you might see in a fish. It is even better than that. The exact focusing of the lens is precisely as it should be. The details of this are written down in Nilsson’s paper. By feeding in assumptions which are based upon field work in population genetics he was able to make calculations as to how long it would plausibly take under realistic conditions of natural selection. This is similar to the Stebbins calculation of how long it would take to go from the start of the series to the end.

Once again it was startlingly fast. Nilsson calculated that it would take fewer than half a million generations. The sort of small animals we are talking about, in which the eye originally evolved, would probably have had about 1 generation/year. Half a million years is a very short time on the geologic time scale.

Therefore, it’s not surprising that when you look around the animal kingdom you find all the intermediates you could wish for in the evolution of the eye, in various groups of worms, etc. The eye has evolved no less than 40 times independently around the animal kingdom, and possibly as many as 60 times. So, “the” eye is really some 40 to 60 different eyes and it evolves very rapidly and exceedingly easily. There are 9 different optical principles that have been used in the design of eyes and all 9 are represented more than once in the animal kingdom.

“Evolution also refers to the unproven belief that random, undirected forces produced a world of living things.”

Where did this ridiculous idea come from that evolution has something to do with randomness? The theory of evolution by natural selection has a random element—mutation—but by far the most important part of the theory of evolution is non-random: natural selection. Mutation is random. Mutation is the process whereby parent genes are changed, at random. Random in the sense of not directed toward improvement. Improvement comes about through natural selection, through the survival of that minority of genes which are good at helping bodies survive and reproduce. It is the non-random natural selection we are talking about when we talk about the directing force which propels evolution in the direction of increasing complexity, increasing elegance, and increasing apparent design.

The statement that “evolution refers to the unproven belief that random undirected forces . . .” is not only unproven itself, it is stupid. No rational person could believe that random forces could produce a world of living things.

Fred Hoyle, the eminent British astronomer who is less eminent in the field of biology, has likened the theory of evolution to the following metaphor: “It’s like a tornado blowing through a junkyard and having the luck to assemble a Boeing 747.” His statement is a classic example of the erroneous belief that natural selection is nothing but a theory of chance. A “Boeing 747” is the end product that any theory of life must explain. The riddle for any theory to answer is, “How do you get complicated, statistically improbable apparent design?” Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection is the only known theory that can answer this riddle. It is also supported by a great deal of evidence. With his explanation Darwin, in effect, smears out the chance or “luck” factor. There is luck in the theory, but the luck is found in small steps. Each generational step in the evolutionary process is only a little bit different from the step before. These little bits of difference are not too great to come about by chance, by mutation. However if, after the accumulation of a sufficient number of these small steps (perhaps 100), one after the other, you’ve got something like an eye at the end of this process, it could not have come all of a sudden by chance. Each individual step could occur by chance, but all 100 steps together could not. All 100 steps are pieced together cumulatively by natural selection.

Another metaphor along these lines is of a bank robber who went into a bank and started fiddling with the combination lock on the safe. Theoretically the thief could fiddle with the lock and have the luck to open the safe. Of course you know in practice he couldn’t do that. That’s why your money is safe in the bank. But just suppose that every time you twiddled that knob and got a little bit closer to the correct number, a dollar bill fell out of the safe. Then when you twiddled it another way and got a little closer still, another dollar fell out. You would very rapidly open the safe. It’s like that with natural selection. Each step has a little bit of luck but when the steps are put together you end up with something that looks like a Boeing 747.

“There are many unanswered questions about the origin of life which are not mentioned in your textbook including: why did the major groups of animals suddenly appear in the fossil record known as the “cambrian explosion.”

We are very lucky to have fossils at all. After an animal dies many conditions have to be met if it is to become a fossil, and one or another of those conditions usually is not met. Personally, I would consider it an honor to be fossilized but I don’t have much hope of it. If all the creatures which had ever lived had in fact been fossilized we would be wading knee deep in fossils. The world would be filled with fossils. Perhaps it is just as well that it hasn’t happened that way.

Because it is particularly difficult for an animal without a hard skeleton to be fossilized, most of the fossils we find are of animals with hard skeletons—vertebrates with bones, mollusks with their shells, arthropods with their external skeleton. If the ancestors of these were all soft and then some offspring evolved a hard skeleton, the only fossilized animals would be those more recent varieties. Therefore, we expect fossils to appear suddenly in the geologic record and that’s one reason groups of animals suddenly appear in the Cambrian Explosion.

There are rare instances in which the soft parts of animals are preserved as fossils. One case is the famous Burgess Shale which is one of the best beds from the Cambrian Era (between 500 million and 600 million years ago) mentioned in this quotation. What must have happened is that the ancestors of these creatures were evolving by the ordinary slow processes of evolution, but they were evolving before the Cambrian when fossilizing conditions were not very good and many of them did not have skeletons anyway. It is probably genuinely true that in the Cambrian there was a very rapid flowering of multicellular life and this may have been when a large number of the great animal phyla did evolve. If they did, their essential divergence during a period of about 10 million years is very fast. However, bearing in mind the Stebbins calculation and the Nilsson calculation, it is actually not all that fast. There is some recent evidence from molecular comparisons among modern animals which suggests that there may not have been a Cambrian Explosion at all, anyway. Modern phyla may well have their most recent common ancestors way back in the Precambrian.

As I said, we’re actually lucky to have fossils at all. In any case, it is misleading to think that fossils are the most important evidence for evolution. Even if there were not a single fossil anywhere in the earth, the evidence for evolution would still be utterly overwhelming. We would be in the position of a detective who comes upon a crime after the fact. You can’t see the crime being committed because it has already happened. But there is evidence lying all around. To pursue any case, most detectives and most courts of law are happy with two to three clues that point in the right direction.

Even discounting fossils, the clues that are left for us to see that prove the truth of evolution are numbered in the tens of millions. The number of clues, the sheer weight of evidence, totally and utterly, sledgehammeringly, overwhelmingly strongly supports the conclusion that evolution is true—unless you are prepared to believe the Almighty deliberately faked the evidence in order to make it look as though evolution is true. (And there are people who believe that.)

The evidence comes from comparative studies of modern animals. If you look at the millions of modern species and compare them with each other—looking at the comparative evidence of biochemistry, especially molecular evidence—you get a pattern, an exceedingly significant pattern, whereby some pairs of animals like rats and mice are very similar to each other. Other pairs of animals like rats and squirrels are a bit more different. Pairs like rats and porcupines are a bit more different still in all their characteristics. Others like rats and humans are a bit more different still, and so forth. The pattern that you see is a pattern of cousinship; that is the only way to interpret it. Some are close cousins like rats and mice; others are slightly more distant cousins (rats and porcupines) which means they have a common ancestor that lived a bit longer ago. More distinctly different cousins like rats and humans had a common ancestor who lived a bit longer ago still. Every single fact that you can find about animals is compatible with that pattern.

Similarly you can look at the geographical distribution of an animal species. Why do animals in the Galapagos Islands more closely resemble animals on neighboring islands and resemble less the animals on the mainland? It’s all exactly what you would expect if evolution goes on in isolation on islands with occasional island-hopping. New foci for evolution start with migration from mainland to island and then progress from there to other islands.

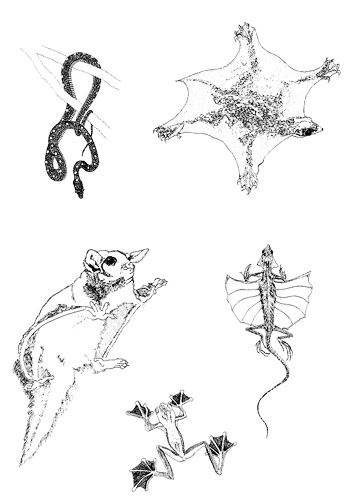

Figure 1.4 - Vertebrates that glide down from trees but do not truly fly: (clockwise from top right) colugo, Cynocephalus volans; flying lizard, Draco volans; Wallaces flying frog, Rhacophorus nigropalmatus; marsupial sugar glider, Petaurus breviceps; and flying snake, Chrysopelea paradisi.

If you look at the imperfections of nature you see evidence for evolution. Figure 1.4 shows animals that don’t necessarily fly but are at plausible intermediate stages on the way to flight. These stages are relevant to the discussion of what’s the use of half an eye or what’s the use of half a wing. These animals all glide and by gliding save themselves from falling out of trees.

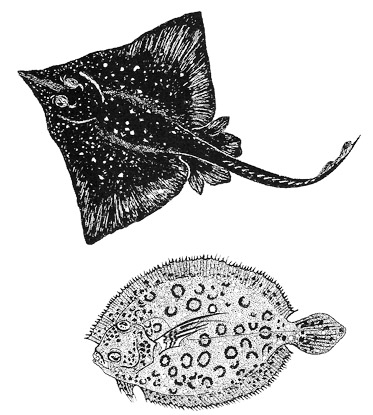

Figure 1.5 - Two ways of being a flat-fish: the skate, Raja batis (top), lies on its belly, while the flounder, Bothus lunatus, lies on its side.

There are two different ways of being a flat fish. The top fish in Figure 1.5 is a skate; the bottom one is a flounder. The skate is flat the way a designer might have designed—flattened out on its belly as symmetrically as it can be. The flounder is not symmetrical because when its ancestors went flat they lay on their side, their right side. That meant that the right eye was looking down into the bottom of the sea (not good). Over many generations, natural selection favored the migration of the right eye from the underside to the top. The whole skull became distorted in an interesting way—no designer would ever have built a fish like that. The flounder has its history written all over it. Its ancestors were once free-swimming in the normal way, like a trout or a salmon, and then over many generations changed into a flat fish.

“Why have no new major groups of living things appeared in the fossil record for a long time?”

We are moving well down the list of the Alabama State Board of Education. In zoology, “major groups” would be called phyla—a phylum being a category such as mollusks, which includes snails and shellfish; echinoderms, which are starfish, sea urchins, and so on; chordates, which are animals with spinal cords, including ourselves; arthropods which include insects and crustaceans. The question is, “Why have no major ones appeared in a long time?”

Well, major groups don’t and shouldn’t, according to the Darwinian Theory, just appear. They evolve gradually. Major phyla are different from each other, though ancestrally they were like brothers. They diverged and became separate species, then separate families, then separate orders. It takes time to do that.

Think of this analogy. Suppose you have a great oak tree with huge limbs at the base and smaller and smaller branches toward the outer layers where finally there are just lots and lots of little twigs. Obviously the little tiny twigs appeared most recently. The larger boughs appeared a long time ago and when they did appear, they were little twigs. What would you think if a gardener said, “Isn’t it funny that no major boughs have appeared on this tree in recent years, only small twigs?” You’d say he is stupid.

“Why do major new groups of plants and animals have no transitional forms in the fossil record?”

It’s amazing how often this is stated in the creationist literature. It’s amazing because it simply isn’t true. There are plenty of transitional forms. There are gaps, of course, for reasons I have stated—not all animals fossilize. But what is significant is that not a single fossil has turned up in the wrong place. Fossils are all in the right order. Creationists know that fossils all appear in the right order and it is quite an embarrassment for them. The best explanation they have come up with so far is based on Noah’s flood. They say that when the great flood came the animals all rushed for the hills. The clever ones all got to the top of the hill while the stupid ones were stuck at the bottom and that’s why the fossils are all neatly laid out in just the right order!

Part of the error about transitional forms may come from a misreading of a theory by my colleagues Niles Eldredge and Stephen J. Gould. Their theory is called “punctuated equilibrium.” It is really about rapid gradualism or, to say it another way, gradual change that occurs rapidly separated by periods of stasis when nothing changes at all. Eldredge and Gould are rightly annoyed about the misuse of their idea by creationists, who in my terminology think punctuated equilibrium is about huge Boeing 747 type mutations. I quote Stephen Gould, “We proposed punctuated equilibrium to explain trends; it is infuriating to be quoted again and again, whether through design or stupidity I do not know, as admitting ‘the fossil record includes no transition forms’. Transitional forms are generally lacking at the species level but they are abundant between larger group forms.” Dr. Gould goes on, “I am both angry at and amused by the creationists and mostly I am deeply sad.”

Finally, there is a semantic point about transitional forms. Zoologists, when they classify, are forced by the rules of the game to put each specimen in one species or another. In the classification business we are not allowed to say, “Well this is halfway between Homo sapiens and Homo erectus.” People who dig up human fossils will always be forced to choose between one or the other. Is it Homo erectus or archaic Homo sapiens? It is forced to be one or the other. Given this definition, it is almost a legalistic point that fossils have got to be classified as one or the other. The analogy I’d offer is this. When you reach the age of majority—legal age—of 18 in Alabama you can vote. So, at the stroke of midnight on your 18th birthday you become an adult. Suppose somebody were to say, “Isn’t it remarkable, there are no intermediates between children and adults?” That would be ridiculous.

“How did you and all living things come to possess such a complete and complex set of instructions for building a living body.”

The set of instructions is our DNA. We got it from our parents and they got it from their parents. We can all look back through the generations, through 4,000 million years to a tiny bacterium who lived in the sea and was the ancestor of us all. We are all cousins.

We can all look back at our ancestors and claim (it’s a proud claim)we are all descended from the elite. Not a single one of my ancestors died in infancy; they all reached adulthood. Not one of my ancestors failed to achieve at least one heterosexual copulation. All our ancestors were good at surviving and reproducing. We are descended from an elite.

Thousands of our ancestors’ contemporaries failed. None of our ancestors did. Our DNA is DNA that has come down through thousands of millions of successful ancestors. We have inherited DNA that is pretty good at the job of surviving and, when DNA survives, it programs bodies to be good at surviving and reproducing. The world is bound to become filled with DNA that is good at surviving and reproducing. The DNA that is alive today has survived thousands of filters. Millions of generations of ancestors that survived, as a consequence of the efficient programming of their DNA, have produced an unbroken lineage. There is more to it than that. Evolution is progressive—not all the time, not uniformly—but generally it is progressive. Lineages become progressively better at what they do. Predators get better at catching prey. They have to because prey become better at getting away from predators. Just as in the human arms race there must be advances on one side to counterbalance advances on the other side.

Just a few examples of animals I would consider to be at the end of an arms race are butterflies and leaf insects (related to stick insects) that look exactly like leaves, and bugs that look like rose thorns and sit on rose stems. All of these are the result of generations of natural selection in which predators have been put off eating the ancestors of these insects. The ancestors that look most like leaves or rose thorns were the least likely to end up in predators’ bellies.

The leafy sea dragon is a fish, related to sea horses. It has “fronds” that look exactly like seaweed for camouflage. This constitutes the end of an arms race in which fish that did not look like seaweed were eaten, whereas fish that did look like seaweed swam on to reproduce another day.

It’s not all just survival, it’s also winning mates. Birds of paradise are brightly colored because that’s what females like. Genes that make pretty males are more likely to get mates and have children. This is an arms race between the salesmanship of males and the sales resistance of females.

Finally, one of the most rapid and dramatic stories of evolution—the evolution of the human brain from the brain of ape-like ancestors. The human brain constitutes the major difference between us and our close cousins, the great apes. Fossil evidence shows that our brain has blown up like a balloon during the last two or three million years as our evolution passed through the ancestral stage Australopithecus, Homo erectus, and finally Homo sapiens. No one knows why the human brain blew up in this way. I suspect again it was like some kind of arms race—some kind of positive feedback.

“Study hard and keep an open mind. Someday you may contribute to the theories of how living things appeared on earth.”

Well, at last we have found something we can agree with. This seems to me to be an admirable sentiment. I really have less trouble than some of my colleagues with so-called creation science being taught in the public schools as long as evolution is taught as well. By all means let creation science be taught in the schools. It should take all of about 10 minutes to teach it and then children can be allowed to make up their own minds in the face of evidence. For children who study hard and keep an open mind, it seems to me utterly inconceivable that they could conclude anything other than that evolution is true.