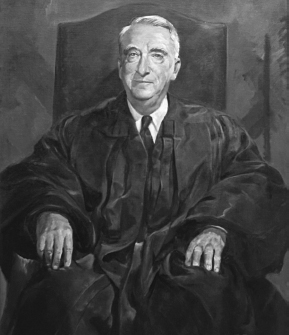

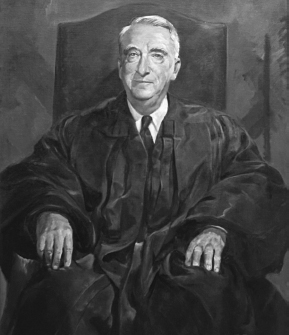

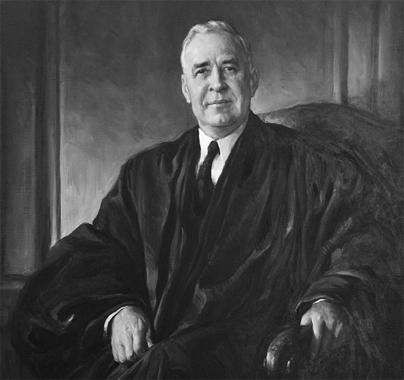

Fred M. Vinson, Chief Justice (1946–1953)

FRED VINSON WAS BORN in 1890 in northeastern Kentucky; he graduated at the top of his class from Centre College, in the city of Danville. After returning to Lawrence County, he embarked on a career of public service. He became a city attorney, then served in the Army during World War I. In 1924, he was elected to Congress, where he remained for fourteen years. While there, he met and befriended Senator Harry Truman, ultimately becoming a confidant of and a participant in card games with the future president. President Roosevelt nominated him as a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in 1937. One of his colleagues on that court was Wiley B. Rutledge, who would later become a justice of the Supreme Court and my first boss after I finished law school.

In 1943 Vinson resigned from the court of appeals to become the second director of the Office of Economic Stabilization—the agency that oversaw the rationing of items in short supply and imposed price and wage regulations on the wartime economy. (The first director of that agency was James F. Byrnes, who had been appointed to the Supreme Court a few months before the outbreak of World War II and had resigned from the Court on October 3, 1942, to accept the newly created position.) Vinson ran that agency during the war, and then President Truman selected him as his secretary of the treasury. In 1946, after Chief Justice Stone suffered his fatal cerebral hemorrhage, Truman nominated and the Senate by voice vote confirmed Vinson to be chief justice of the United States. He served until his death, on September 8, 1953, a few months before Brown v. Board of Education was to be reargued.

Willard Pedrick, a young lawyer who had worked for Vinson as a law clerk on the court of appeals and in an executive capacity during the war, joined the faculty of Northwestern University Law School shortly after I became a student, in the fall of 1945. He was the source of the cordial relationship between Chief Justice Vinson and Northwestern that developed later.

My relationship to Vinson had its roots in the spring of 1947, when I was finishing law school and Congress statutorily increased the funds available for the employment of law clerks. The increase enabled four associate justices—including Justice Rutledge—to hire two law clerks each year, while the chief justice hired three. The chief received the extra law clerk because his chambers reviewed all of the in forma pauperis petitions (cases in which the petitioner is too poor to incur the cost of printing relevant court documents) that indigent prisoners filed to challenge the constitutionality of their convictions. It was the job of the chief’s clerks to prepare memoranda summarizing each such petition and recommending an appropriate disposition. Each of the associate justices received a carbon copy of the original typed document; almost invariably, the chief’s clerk recommended “deny,” explaining that the prisoner had not exhausted his state remedies or that the claim had no merit.

Before Vinson began employing a third clerk, the substantial burden that in forma pauperis petitions imposed might also have been alleviated by relieving the chief’s chambers of the responsibility to make a preliminary review of each in forma pauperis petition. When the same problem arose some years later—after the number of in forma pauperis petitions increased dramatically from 1946 levels—the latter course was followed, and the clerk’s office began making copies of all in forma pauperis filings and distributing them to all nine chambers for individual review. Given the state of copying technology in 1946, however, Congress apparently decided that an extra law clerk’s salary of $5,400 was a bargain in comparison to the cost of making nine copies of each one of those papers.

When that statute was passed, Art Seder and I were coeditors of the law review at Northwestern with grade point averages that placed us at the top of the graduating class. We were then completing a three-year course of study in an accelerated program that consumed just two calendar years. The program was popular because most members of the class were recently discharged veterans of World War II eager to become productive participants in the civilian economy as soon as possible. Art, for example, had flown twenty-five missions over Germany as the pilot of a four-engine B-17 bomber, and I had spent most of the war at Pearl Harbor studying intercepted Japanese radio transmissions. I think there were only three women in the entire law school at that time.

That spring, two of our professors—Willard Pedrick, whom I have already described, and Willard Wirtz, who had been on the faculty at the University of Iowa’s law school when Wiley Rutledge was the dean and who later became the secretary of labor in John F. Kennedy’s and Lyndon Johnson’s administrations—advised us that they had persuaded two Supreme Court justices to hire Northwestern graduates as law clerks. One prospect was for a one-year job beginning at the end of the summer with Justice Wiley Rutledge, and the other was for a two-year job with Chief Justice Vinson beginning a year later. They told us that they considered us equally qualified and that they could not decide which of us to support for which clerkship. They delegated the decision to us. I won the coin flip and reported for duty with Justice Rutledge in September. Art began his work with the chief justice a year later. The other seven justices active during our tenures as clerks were Hugo Black, Stanley Reed, Felix Frankfurter, William Douglas, Frank Murphy, Robert Jackson, and Harold Burton.

Wiley B. Rutledge, Associate Justice (1943–1949). 1947, oil on canvas by Harold Brett. Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

My appraisal of Chief Justice Vinson is based on my own clerkship, what I learned later from Art, and, of course, information in the public domain. Fred Vinson was President Truman’s second appointee to the Court. Truman had previously appointed Harold Burton, who had served with him in the Senate, and he later appointed Sherman Minton, also a former colleague in the Senate, and Tom Clark, who was his attorney general when Art and I were in law school. Burton was the only Republican that Truman named. Because each of Truman’s nominees had previously worked closely with him in the Senate or the executive branch, it is fair to infer that the president’s firsthand knowledge about their characters and qualifications played a more important role in his selection than any recommendations made by lawyers, bar associations, or political sponsors.

In 1948, during the spring of my clerkship, President Truman hosted a reception at the White House for federal judges and their clerks. As a Republican, I was not a special admirer of Truman, but I still vividly remember the favorable impression that he made when he greeted me in the receiving line. He was a genuine, friendly guy whom I liked right away. So, although I voted for Dewey in the election that fall, I found myself pulling for Truman while listening to the returns.

I did so despite my adverse reaction to the timing of his appointment of Rutledge’s successor a few weeks earlier. A year after my clerkship with him ended, Justice Rutledge had a stroke while driving, and he died two weeks later, on September 10, 1949, at the age of fifty-five. Because his excellence as a scholar and a judge was so well established, his premature death was an especially sad occasion for his host of friends and admirers. As I left the church following the funeral services, I was startled to find a newsboy hawking papers with headlines proclaiming that Truman had nominated Sherman Minton to fill Rutledge’s seat. Perhaps my grief at the time has colored my views, but I thought then and have often commented since that Truman’s announcement was an unnecessarily prompt and somewhat disrespectful response to a tragic event.

I recall mentioning this to Tom Clark in the 1970s. After serving as attorney general, Clark was appointed to the Supreme Court by Truman, and he proved to be unquestionably the strongest of the four Supreme Court appointments that Truman made. As I explained, we became good friends while I served on the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals. His response to my comment sheds some light on the process by which Truman nominated Supreme Court justices.

Sherman Minton was a judge on the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals; he had formerly served with Truman in the Senate. Tom told me that Minton was at home in New Albany, Indiana, when he read the newspaper’s report of Rutledge’s death. He immediately bought a railroad ticket, boarded the overnight train to Washington, and, upon his arrival, took a taxi to the White House. Without any advance notice, he arrived at the gate, identified himself, and told the guard that he wanted to see the president. He was promptly admitted and taken to the Oval Office. As Tom Clark related, Minton simply told his friend, former colleague, and the current president that he wanted the job that Rutledge’s death had made available. Truman agreed on the spot, and Minton became his third appointment to the Court soon thereafter. Perhaps I am prejudiced, but I never thought that he had a love or understanding of the law remotely comparable to Rutledge’s.

I know nothing about the process that Truman followed when he selected Fred Vinson to succeed Harlan Stone. In light of Clark’s story, however, it is reasonable to infer that a friendship that included regular poker games and frequent telephone conversations played a role in the decision.

In his first term as chief justice, Vinson selected Byron White as one of his law clerks. Byron was an All-American athlete in football and basketball, a Rhodes Scholar, a World War II Navy intelligence officer who had survived kamikaze attacks in the Pacific, and a top graduate of Yale’s law school. He was also the first former law clerk to become a justice. (Bill Rehnquist was the second, I was the third, and Stephen Breyer—who clerked for Justice Arthur Goldberg—was the fourth.) Byron was appointed to the Court by President Kennedy in 1962 and served for thirty-one years. It was Byron’s conduct as a clerk that gave rise to the Court’s adoption of a strict rule that has remained in place for sixty-five years. Byron regularly shot baskets in the gym on the third floor, which was immediately above the courtroom. On one occasion, he was practicing layups as his boss was presiding over an oral argument in the room below him. Whether the sound of his bouncing ball had an impact on the outcome of that case is not known, but Byron never denied responsibility for Vinson’s promulgation of an unwritten rule that is still in effect today: While the law clerks are allowed regular late-afternoon games—in which, by the way, Byron participated for years after becoming a justice—no basketball is permitted in the gym while the Court is in session.

It is quite clear that President Truman continued to have the greatest respect for Vinson in the years after he became chief justice. For instance, in 1948, when relations with the Soviets were at a particularly low ebb, the president considered sending Vinson to Russia on a diplomatic mission. Vinson mentioned this proposed mission to Moscow to his law clerks so often that Art became excited about the possibility that Vinson might take a law clerk with him. Instead, the State Department torpedoed the idea.

This closeness did not, however, prevent deference in Vinson’s interactions with Truman. Well aware of the men’s warm relationship, Art Seder was surprised to overhear Vinson address his close friend as Mr. President in a telephone conversation.

That deference may have influenced Vinson’s vote in the landmark case of Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952). That case arose during the Korean War, when defense contractors needed massive amounts of steel. Concerned that an impending strike would disrupt the steel supply, Truman seized control of the mills. The steel companies sued, challenging the constitutionality of the seizure, and the Court held, by a vote of six to three, that the executive power vested in the president by Article II of the Constitution did not authorize his seizure of privately owned steel mills, despite the existence of a national emergency. The fact that two Truman appointees—Justices Burton and Clark—joined the Court’s judgment exemplifies the independence of the federal judiciary. Although the three dissenters included the two other Truman appointees—the chief justice and Justice Minton—the fact that Justice Reed joined the chief’s dissent demonstrates that this position, too, was not without arguable merit. (There is a nonfrivolous rumor that the president’s decision to seize the steel mills may have been influenced by something that Vinson said while playing poker with him one evening during the emergency.) The limits on the power of the president imposed by that decision have been respected ever since.

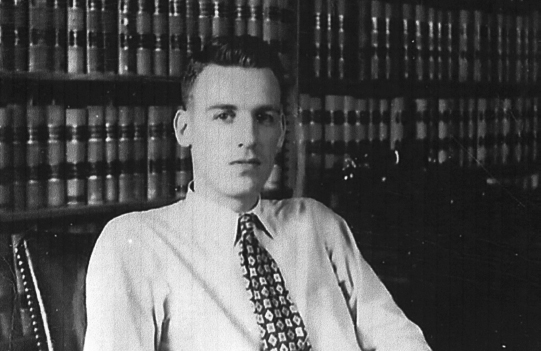

Arthur Seder, law clerk to Chief Justice Vinson (1948–1949 term). Used with permission of Arthur Seder.

Art Seder regarded Vinson as a confident and competent chief. Though a decisive judge, he was by no means the intellectual leader of the Court. Three of his colleagues—Felix Frankfurter, Bill Douglas, and Wiley Rutledge—had exceptional and superior academic credentials. Frankfurter had been among the nation’s leading public intellectuals while a professor at Harvard Law School before joining the Court. Though Douglas’s academic tenure was shorter, it was also distinguished, and it included positions at Columbia and then Yale. Wiley Rutledge’s law school teaching matured in deanships, first at the Washington University School of Law and then at the University of Iowa School of Law. Three members of the Court—Hugo Black, Robert Jackson, and Stanley Reed—had extensive experience in trial and appellate litigation, which Vinson did not. Black worked as a private attorney, prosecutor, and local judge before leading investigations as a United States senator for Alabama. Prior to Jackson’s appointment to the Court, he had been both solicitor general and attorney general in FDR’s administration. And Reed had also served as solicitor general before joining the bench. To quote Art: “One would think Vinson might have been a little overwhelmed—he a country lawyer from a small town in Kentucky—sitting at the head of a table surrounded by law professors and others whose careers had been made in the practice of law. But if so, he never gave any open sign of discomfort.”

Vinson was not a writer either and may have had a little difficulty following some of the more esoteric arguments advanced by counsel. Nonetheless, he had confidence in his ability to identify which outcome of a case would, in his judgment, best serve the public interest. In Art’s words, he “gave his law clerks very few instructions about how they should write drafts of his opinions, but he was very clear about the result he wanted.” In discussing cases with his clerks after the Saturday conferences, Vinson cogently described the positions of each justice and readily answered the clerks’ questions. Those candid and detailed postconference sessions made it clear to his clerks that the chief was well qualified to serve as the equal of every one of his colleagues.

Sharing the views of other law clerks during the 1947 term (and thus not including Art Seder’s), I was not an especial admirer of the chief. My boss was frequently one of four dissenters. In Fourth Amendment cases, he and Frank Murphy shared the views of Frankfurter and Jackson, while in antitrust cases they tended to agree with Black and Douglas. I do not recall any five-to-four decisions in which Vinson and Rutledge agreed, but I do recall one case in which it was Rutledge who wrote for the majority over Vinson’s dissent. Only one other justice—Jackson—dissented from my boss’s narrowly written opinion in that case, Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan (1948).

Bob-Lo presented the Court with an opportunity to overrule its unfortunate precedent in Hall v. DeCuir (1878). In DeCuir, the Louisiana Supreme Court had affirmed an award of damages to a woman of color who had boarded a steamboat in New Orleans, Louisiana, to travel to Hermitage, Louisiana, and then been refused accommodation in a cabin set apart for white persons. The Supreme Court reversed on the ground that because Louisiana’s attempt to protect its citizens from racial discrimination involved an interstate carrier—the steamship continued on to Mississippi, where state law could require separate accommodation for nonwhite passengers—its actions violated the commerce clause of the federal Constitution. Today that Court decision seems patently wrong because the Louisiana court was simply enforcing a state law that was fully consistent with the objectives of the then recently enacted post–Civil War amendments as well as the common-law duties of public carriers. It is also remarkable because the Court thought that its result was compelled by the absence of congressional action—that is, it thought that the Constitution barred Louisiana’s ban on race discrimination when Congress had said no such thing.

In Bob-Lo, the owner of a vessel that made daily round trips between Detroit and a Canadian island in the lower Detroit River argued that the enforcement of its “whites only” policy against an African American high school student enjoyed similar constitutional immunity, in this case from a Michigan antidiscrimination statute, because its vessel was engaged in foreign commerce. In an uncharacteristically short majority opinion, Justice Rutledge distinguished the DeCuir case—which is to say, explained that it was relevantly different from Bob-Lo—on the narrow ground that unlike the potential conflict between the Mississippi and Louisiana laws, in Bob-Lo, Michigan law, Canadian law, and federal law all prohibited discrimination on the basis of race and so presented no risk to carriers of conflicting legal obligations. Justice Douglas, joined by Justice Black, indicated in a concurring opinion that they would have overruled DeCuir. The chief, by contrast, joined Justice Jackson’s dissenting view that the interest in protecting foreign commerce from burdensome state laws was of primary importance. The dissenters’ reliance on DeCuir suggests that they were less concerned about discrimination against a nonwhite passenger than about the modest—indeed, trivial—potential burden on the shipowner. In the end, the Court affirmed the judgment finding the defendant guilty of violating Michigan’s Civil Rights Act and requiring the company to pay a fine of twenty-five dollars.

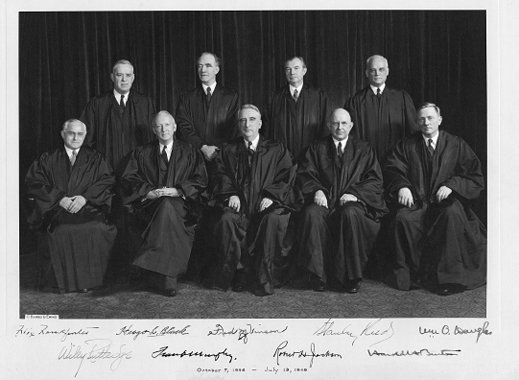

Formal group photograph of the 1946 Vinson Court.

Seated from left: Justices Felix Frankfurter, Hugo L. Black, Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson, and Justices Stanley Reed and William O. Douglas. Standing from left: Justices Wiley Rutledge, Frank Murphy, Robert H. Jackson, and Harold H. Burton. C. 1946. By Harris & Ewing, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

The cases in which Rutledge dissented that troubled me the most were Bute v. Illinois (1948), holding that Illinois did not have to appoint counsel for a defendant charged with a felony carrying a twenty-year sentence, and Ahrens v. Clark (1948), holding that enemy aliens did not have access to the writ of habeas corpus because they were being detained on Ellis Island rather than in the District of Columbia, where their custodian—the attorney general—was located. Happily, both of those cases have since been overruled. Indeed, in a recent narcotic-possession case, the Court held that even an alien’s right to counsel may be violated by a lawyer’s incorrect advice that his guilty plea would not lead to his deportation. And rejection of the narrow reading of the habeas corpus statute played a critical role in the Court’s conclusion that the writ was available to detainees in Guantānamo. Even terrorists allegedly sharing responsibility for the attack on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, may seek judicial review of the basis for their detention.

Despite my misgivings about Vinson’s judgment in some of the cases that the Court decided during my one-year clerkship, he undoubtedly came out on the right side in the two most important cases of the term, both of which he authored. Those opinions came in the restrictive-covenant cases Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) and Hurd v. Hodge (1948), which provided me with an opportunity to see Thurgood Marshall—then chief counsel for the NAACP—argue before the Court (he also argued three other cases that term). Justice Rutledge and two other justices did not participate in those cases, presumably because they owned property burdened with covenants prohibiting their sale to African Americans. If there had been a three-to-three vote among the six justices who were not disqualified, they would merely have entered an order stating that the judgments had been affirmed by an equally divided Court. Fortunately, however, they unanimously held that judicial action enforcing such covenants is prohibited by the Constitution. Their exceptional importance merits brief comment.

The first of the two restrictive-covenant cases arose in Missouri and Michigan. The decision rested on an interpretation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment—a provision that prohibits “any State” from denying to any person within its jurisdiction “the equal protection of the laws.” The decision prohibited a widespread and odious form of racial discrimination in every state of the union. Because the second case arose in the District of Columbia—which, of course, is not a state—the Fourteenth Amendment was inapplicable. In order to reach the same result in that case, it was necessary for the Court to find another source for the government’s duty to govern impartially that was expressly protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. Vinson found two: a federal statute applicable to Washington, D.C., that stated the same policy as the Fourteenth Amendment and a rule announced in earlier cases that federal courts should not enforce private agreements that contravened the public policy of the United States, including the requirement of equal protection expressed in the Fourteenth Amendment. Thus, simple justice rather than constitutional text dictated the result. Together, the two cases protected the right of an African American to purchase property anywhere in the United States despite the existence of a covenant prohibiting the purchase from taking place.

Because of the importance of these holdings, the chief justice appropriately assigned himself the opinions in both cases. I have always believed that they were drafted by his clerk Frank Allen, a brilliant scholar who later became dean of the University of Michigan Law School. Frank was also a graduate of Northwestern; the quality of his work, like that of Art’s, no doubt influenced Vinson’s later decisions to have two Northwestern graduates as law clerks during succeeding terms.

While the chief justice is an equal of the other justices when he votes on a case, he is first among them in shaping many of the internal workings of the Court. It is here that some chiefs have had their greatest influence. Indeed, the procedures that Chief Justice Fred Vinson followed are quite different from those in place today.

While the Court has continued the Vinson-era practice of holding seven two-week oral argument sessions during each term, the number of argument days in each of those weeks has been reduced; whereas there were five a week under Vinson, there are only three a week today. Except for the few cases on what was called, in the Vinson period, the summary docket, each side was allowed a full hour for argument.

What is now a two-hour morning session beginning at 10:00 was, when Vinson was chief, a session that began at noon and lasted until 2:00 p.m. There was then a half-hour luncheon break before the Court reconvened at 2:30, meaning that hungry justices sometimes ate a little too much and found it difficult to remain alert during the afternoon session, which lasted until 4:30. On more than one occasion, Justice Rutledge thought it necessary to give Frank Murphy, his neighbor on the bench, a jab or two to make sure that he was awake.

The questioning of advocates at oral argument during Vinson’s tenure reflected the particular personalities of contemporary members of the Court. On occasion, Justice Rutledge returned to chambers after argument quite obviously pleased with the fact that an experienced lawyer had been unable to make an effective response to his question. I have no memory of any questioning by the chief. I do recall, however, that the justice who was by far the most active in posing questions to counsel during oral arguments was Felix Frankfurter. Sometimes I received the impression that he had not yet read the briefs and was relying on counsel to identify the exact issue in dispute. On other occasions he treated the advocate in a way that reminded me of a law professor dealing with a student who needed to be told what earlier cases had decided. I recall one colloquy with Thurgood Marshall, then an attorney appearing before the Court, in which Felix reiterated his understanding of a precedent several times and Thurgood firmly adhered to his position, respectfully stating more than once: “That is not how I read the case.” Though Thurgood was unlikely to win that point with Felix, he was a remarkably talented advocate. For example, in arguing a challenge to segregated legal education in Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma, Thurgood was so persuasive that his oral arguments ended on a Thursday and on the following Monday the Court ordered the University of Oklahoma to admit his client, Ada Sipuel, to its law school. Years later, while playing golf with an Oklahoma graduate who had been one of Ada Sipuel’s classmates, I was pleased to learn that the students had welcomed her as a friend despite the state’s attempt to enforce its exclusionary policy.

The five-days-a-week oral argument schedule under Vinson made it necessary for the Court to set Saturdays aside for the conferences at which the justices discussed and usually decided the merits of each case. Those conferences differed from those held in recent years in three significant ways—the processing of petitions for review, the determination of what opinions were ready for public announcement, and the discussion of how to decide the cases argued during the preceding week.

The normal procedure in the Saturday conferences in 1947 included a discussion of almost every petition requesting that the Court review a lower court decision; the only exceptions were a relatively small number of cases that the chief considered too frivolous to merit discussion. He would identify those cases on a dead list circulated on Friday, but even cases that the chief had dead-listed would be discussed if any member of the Court so requested.

During the time that Vinson was the chief, however, that strong presumption in favor of discussing almost every case ready for disposition changed. Since 1950, the reverse presumption has maintained. Under the new procedure, before each conference, the chief justice circulates a discuss list, identifying cases ready for disposition that he considers worthy of discussion. Any justice may add cases to that list, but other than those additions, the requests for review that failed to make the discuss list will be denied. This difference in procedure is adequately justified by the fact that only 1,510 cases were filed in Chief Justice Vinson’s first term in 1946 whereas 8,521 filings occurred during Chief Justice Roberts’s first term in 2005.

In the Vinson era, when the print shop returned the first printed draft of an opinion to its author, his messenger delivered one copy of it to each of the eight other justices’ chambers. In the Rutledge chambers—and I assume in the others as well—that copy went directly to the justice, who normally responded without even consulting his law clerk unless the draft presented a question prompting further deliberation. If the responding justice agreed with the draft, he would usually write the words Please join me on the draft itself and return it to the author. The Saturday conference would be the occasion when the author could inform his colleagues about the status of his circulating opinions.

Today, first drafts are circulated in multiple copies, enabling law clerks to provide the justice with comments before the justice joins, suggests changes, or advises the author that he or she intends to write separately. During my years on the Court, I used the traditional “please join me” formula for expressing my unqualified agreement with the author, even though my join was written in a separate letter rather than on the back of a copy of the opinion. And since copies of join letters, as well as letters asking for changes or announcing planned dissents, are now routinely circulated to all chambers, there is seldom any need for an extended discussion of the status of circulating opinions.

The most important business at conference is the decision of the cases that have been argued and submitted since the prior conference. In the 1947 term, the chief justice introduced the discussion of each case, and the other justices then spoke in order of seniority. (Because there was no limit on the time that each might speak, I understand that Justice Frankfurter occasionally provided his colleagues with comments akin to a fifty-minute classroom lecture.) After everyone had had an opportunity to speak, the voting began. The junior justice voted first, followed by the others, in reverse order of seniority.

Sometime between 1947 and 1975, when I joined the Court, it became regular practice for the justices to announce their votes during their initial comments. Bill Rehnquist, before he became the chief, and I sometimes stated that we thought that the practice followed during the years when we had been law clerks was preferable because, as the two most junior justices, we thought our opportunity to persuade our more senior colleagues was lessened once they had announced their votes. When he served as the chief, however, Bill’s views on this issue changed. Mine have not.

The staff of the entire Court, as well as the staff in each justice’s chambers, is larger today than it was in 1947. Instead of one or two law clerks, each associate justice is now authorized to employ four. Notwithstanding this increase in the clerk-to-justice ratio, there is now more interaction between justices and clerks working in other chambers than there was in 1947. The justices now have a joint reception to which all clerks are invited; the clerks in each chamber customarily invite each of the other justices to lunch once a term; and there is both a Christmas party and an end-of-term party to which all justices and clerks are invited. No such routine contact between justices and clerks working in other chambers occurred in 1947. Like all of the other clerks, I did, however, have a number of spontaneous and stimulating conversations with Justice Frankfurter. (A topic to which he returned more than once with me and others was what he regarded as the Court’s mistaken conclusion that tidelands oil belonged to the federal government rather than to the coastal states.) I think all of us had some occasional contact with every other member of the Court. I especially recall one meeting with Justice Black, and another with the chief.

Justice Black, a former United States senator who had excelled in the competitive world of electoral politics before joining the Court, played tennis regularly on a court in the backyard of his home in Alexandria. He once invited me to play singles with him. During the ride to his house, he impressed me as a gentle, soft-spoken man; on the court he turned into a fierce competitor. I easily won the first set, but he was the victor in a long, hard-fought second set. I was really disheartened and surprised that a sixty-two-year-old man was in so much better physical condition than I was.

As chief justice, Fred Vinson was ably assisted by Edith McHugh, an especially competent secretary who might also have been characterized as somewhat officious. Art Seder told me that she kept track of the number of times that the chief disagreed with his clerks’ recommendations on whether to grant or deny petitions for certiorari, and she seemed to enjoy giving the clerks what she regarded as failing grades. My foremost memory of her concerns a morning that she called Justice Rutledge’s secretary, Edna Lindgreen. Edith advised Edna that the chief justice wanted to meet with Justice Rutledge, quite obviously expecting that Justice Rutledge would come to the chief’s chambers to do so. When Edna conveyed this apparent summons to Justice Rutledge, he told her to advise the chief’s secretary that he would be happy to welcome the chief whenever it was convenient for the chief to come to our chambers. My memory of Vinson’s arrival a few minutes later is a continuing reminder of the status of the chief justice as just one of nine equally powerful decision-makers.

In 1947, commuting to and from work was one area in which there was not complete equality among all nine members of the Court. Each justice had a messenger responsible for delivering papers to the chambers of other justices and for serving lunch to his boss. The justices ate (and paid for) the food that was prepared in the public cafeteria, sometimes eating in the justices’ spacious dining room on the second floor and sometimes in their own chambers. The messenger was available to drive for the justice (or his wife) in the justice’s own car. Chief Justice Vinson’s car and driver were, on occasion, put at Mrs. Vinson’s service. When that happened, Vinson’s law clerk might be given a particular nonlegal assignment. As Art Seder described it, “When Mrs. Vinson had commandeered the chief’s car and it was time to go home, he frequently asked me for a ride in my car. I had a beat-up old 1938 Ford at the time, but the chief squeezed himself in and we rattled and bumped our way to the Wardman Park, where they lived. There the doorman was always ready to order me off the premises until he saw the chief justice emerging from the car, when his attitude changed markedly. I always enjoyed that experience.”

Chief Justice Vinson also contributed to one of my earliest and more memorable professional successes in private practice. While still a law clerk in 1947, I helped Justice Rutledge draft his concurring opinion in Marino v. Ragen, a case reviewing a denial by the circuit court of Winnebago County, Illinois, of Marino’s application for a writ of habeas corpus challenging the constitutionality of his conviction. Illinois law did not provide for appellate review of such orders in the state system. As a result, the only Court with jurisdiction to review the state trial judge’s denial of the writ was the Supreme Court of the United States.

Marino had been in prison since 1925 as a result of having pleaded guilty to murder. He had been eighteen years old at the time, in the country for less than two years, and unable to speak English. No lawyer was appointed to represent him; instead, the arresting officer served as his interpreter. After the case arrived in our Court, the Illinois attorney general confessed error, acknowledging both that Marino’s twenty-two-year-old conviction was invalid and that Marino had invoked the proper state remedy. Justice Rutledge joined the judgment setting aside Marino’s conviction but wrote separately to explain why he believed that the three postconviction remedies available to Illinois prisoners—common-law writ of error, habeas corpus, and coram nobis—constituted a procedural labyrinth made up entirely of blind alleys. In his judgment, these arcane procedures were virtually useless, and the possibility that the Illinois attorney general might eventually confess error in flagrant cases was not an adequate state remedy. He noted that during the preceding three terms, about half of all the in forma pauperis petitions alleging violations of constitutional rights had been filed by Illinois prisoners.

Just over a year later, possibly influenced by Rutledge’s opinion, the Illinois General Assembly enacted a new postconviction remedies act that simplified the procedures available to convicted prisoners. In a speech to the American Law Institute in 1949, Vinson commented favorably on the state’s elimination of its “blind alleys,” noting that many, if not most, of the cases in which the Court has spelled out the requirements of a fair trial had come up as in forma pauperis petitions.

Despite the clarity of the text of the new Illinois statute, state judges continued to use boilerplate orders to deny prisoners any hearing in cases asserting constitutional claims. Finally, in 1951, in three cases argued by my former law professor and ongoing role model Nat Nathanson and decided in an opinion written by Chief Justice Vinson, the Court effectively directed the Illinois Supreme Court to decide whether the state statute meant what it seemed to.

When the case was sent back to Illinois for further proceedings in state court, I was practicing law, and Nat asked me to represent two of the three petitioners, Julius Bernard Sherman and Arthur La Frana. I agreed to do so. On my first trip to the state prison in Joliet, I interviewed Sherman, who alleged that the police had forced him to sign his confession. In the text of the confession, he had written something to this effect: “I have signed this confession because I insisted on doing so.” It seemed likely that that comment had been dictated by a threatening police officer rather than composed by Sherman himself, so I expected to meet a client eager to tell his side of the story in open court. Instead, I met a man who could have been a defensive tackle for the Chicago Bears and who showed little interest in discussing his pending case. It was not that he was not happy to see me; he was. But he welcomed me as a lawyer for another reason. As he explained, he needed advice about how to patent the invention that he was perfecting. When I asked him to describe his invention, he identified it as a new method of digging tunnels. While I respected his judgment about the possible utility and demand for such a device in Joliet, I was unable to assist him.

My visit to Joliet to interview Arthur La Frana was more productive. He had been convicted of murdering a theater cashier in 1937. His petition under the new postconviction remedies act alleged that the police had handcuffed his arms behind his back, hoisted him until his feet almost left the floor, and then beat him until he agreed to confess. Unlike Sherman, La Frana did not have a particularly striking physical appearance. He was of average size and did not look like a man who would assault a defenseless victim. He was courteous and articulate. The most memorable moment of our first meeting came when I asked him to describe the most severe pain caused by the handcuffs, expecting him first to refer to his wrists. He instead described excruciating pain in his upper arms and shoulders. I was surprised but also convinced that he was telling the truth. That conviction motivated a more thorough search for corroborating evidence than I might otherwise have undertaken. Among the evidence that we found was a county jail medical record describing the injuries to his wrists, a news photo taken of La Frana when the police announced that they had solved the case, the testimony of his former wife, who was present in the police station at the time, and the information that several days elapsed between the confession and his transfer from police custody to the county jail. Most persuasive, however, was the incredible explanation for his injuries offered by the police captain: La Frana had fallen down the stairs when allowed to use the men’s room. There was simply no possibility that the fall the captain described could have produced the injuries that the record established. There was also no explanation for the delay in transferring custody of La Frana to the county jail other than officers’ hope that the healing process would eliminate the bruises that appeared in the photograph that we made a part of the record.

Ultimately, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled in our favor, and La Frana was released. A critical step in the process that led to the termination of his seventeen years of wrongful incarceration was the opinion that Fred Vinson announced in 1951.