Periodization refers to the manipulation of training variables over specific periods of time for the purpose of promoting maximal performance at the appropriate time and decreasing the risk of overtraining (8). Periodization, although sometimes misunderstood and not always applied effectively, is not a new concept. It has been around since the ancient Greeks. Flavius Philostratus (AD 170-245), a Greek philosopher and sporting enthusiast, wrote extensively about these periodized methods used by the ancient Greek athletes (2). Periodization should not be thought of as a set model that can be applied in the same manner to all tennis players. The beauty of periodization is that it is a dynamic concept which can be individualized to each athlete’s strengths and weaknesses and can be aimed at helping them perform at their highest levels when it counts the most. Organized and planned programs that have been periodized have been shown to lead to greater performance improvements than nonperiodized programs (6). These periodized programs are not just for professional players; rather, every competitive tennis player should be on some form of a periodized program.

Individuality – A 10-year old female tennis player is not going to respond to the same stimulus as Andy Roddick. This is where a solid understanding of physiological changes throughout development is helpful, as is a consistent testing and monitoring program to understand each athlete’s individual capabilities so he/she can train accordingly. Every tennis player should be on a specific program based on his or her own strengths and weaknesses. A group program where every athlete does the same routine is not going to be the best way to optimize each individual athlete. Some athletes can handle greater physical stress and recover sooner than others. Without solid records it is difficult, if not impossible, to accurately monitor athletes and to optimize their programs.

Specificity – How close are the activities to what will be experienced during competition? The closer the athlete can experience movements, feelings, and situations that will be experienced during competition, the better prepared the athlete will be. Also, a periodized program allows for certain periods throughout the year to focus on more general areas and other times that will focus on more specific areas to tennis performance. A balance is needed between good general physiological development (i.e., increased muscle mass and decreased 10 m sprint times) as well as tennis-specific movement patterns (i.e., medicine ball service throw or movement in the volley and overhead drill).

It is important for the coach or trainer who works with tennis athletes to understand the physiological, biomechanical, and psychological reasons behind each exercise as well as how different exercises can positively or negatively influence other exercises in the program. A good example of how many coaches do not apply the rule of specificity is seen when training for tennis endurance. Many coaches still have athletes run at a slow continuous pace for 30-45 minutes in a hope of building aerobic endurance. This slow, continuous exercise will build aerobic endurance, but it will not simulate the typical movements and work to rest ratios seen during tennis play. Therefore, this type of training does not result in a strong carryover to on-court performance and could actually hinder speed development due to the development of slow twitch (IIa) muscle fibers.

Adaptation – The number one goal of any training program is to create positive adaptations. Increasing muscle mass, decreasing fat mass, increasing ball velocity, and decreasing the time it takes to recover from hard-fought matches are all positive adaptations to training. While attempting to speed adaptation time, many athletes train and perform in a state of overload. This overload is positive adaptation for a short period of time, but many athletes are in this state for too long, and it graduates into a state known as overtraining. Overtraining results in negative consequences and reduced performance. This overtraining can cause problems such as reduced performance, poor sleep, increased injury, slower recovery, minor colds and if training is not reduced can lead to longer term problems such as chronic fatigue (3). A major purpose of periodized programs is to avoid this overtraining problem by cycling work volumes, intensities and sufficient rest periods (5).

Recovery – Recovery or regeneration is sometimes a forgotten part of training. To make continual improvements, adequate recovery is required to allow the body to adjust to the increases in workload and to help avoid long-term fatigue and chronic injuries (5). Recovery is an area that has received more research focus in the last decade, yet it is an area that could provide the biggest area for performance improvement in the future. Understanding workto-rest ratios, hormonal changes, endocrine function, blood chemistry, and circadian rhythms can influence the individual differences in how tennis athletes recover from exercise.

Recovery techniques:

Periodization involves the manipulation of volume and intensity of training through specific periods or seasons of the year. A periodized program can be as short as one week or as long as an athlete’s entire career. As would be expected, the short-term planning focuses on much more detail, including reps, sets, and rest periods, whereas the long-term planning is more focused on the overall purpose of certain periods in a long-term plan.

As we will see later in this chapter, periodized program can be created for the seven major aspects involved in optimizing tennis performance:

All seven aspects should be designed to work together in a well-rounded program to help create the optimum outcome for each area by manipulating the frequency, intensity, volume, recovery, and time of year.

Before a structured periodized program can be put together, a needs analysis is performed to determine the most beneficial type of training for the athlete. The needs analysis involves testing for strengths and weaknesses in as many aspects of the performance as feasible. The amount of testing and the time spent on the periodized program is dependent somewhat on the level of player. A high-level national or international junior player will have a much more detailed periodized program than a 3.5 league doubles player. However, both these players would benefit greatly from having a structured, well-thought-out program. Another important aspect of the needs analysis is to determine the major times of the year the player wants to be competing at his or her highest level. For a college player it might be at the conference tournament, while a professional player might point to the four grand slam tournaments. Areas to be tested in a needs analysis are:

The periodized conditioning program is divided into cycles. In most cases the term macrocycle is used to describe a yearly general plan. For junior and professional tennis players, using macrocycle to describe a yearly plan is the most appropriate; in some circumstances it may be appropriate to have two macrocycles in one calendar year. However, for the majority of instances it is just as effective to follow the calendar year for a macrocycle.

Each macrocycle contains a period of months (typically a season) called a mesocycle. A macrocycle could contain anywhere from 2-10 mesocycles, depending on the focus of the periodized program. Here is an example of mesocycles on the professional circuit: first mesocycle—hardcourts (Jan-April), second mesocycle—claycourts (April-June), third mesocycle—grasscourts (June-July), fourth mesocycle—US hardcourts (July-September), fifth mesocycle—Indoor (September-November), sixth mesocycle—offseason/preseason (November-December). Each mesocycle can be of different durations. The above mesocycles would be different for a clay court specialist who would prefer to play a larger part of his or her schedule on the clay courts, from March to August.

A microcycle is the term used to describe planning for several days. This is typically a 7-day calendar week; however, it is not uncommon to have 10-14-or 21-day microcycles. Each cycle has a specific training goal, and the training variables are manipulated in order to achieve that goal. The following are some common training phases that can be employed when designing a periodized program.

The General Preparatory Phase (GPP) is usually an introductory phase of training, either for a beginning athlete or an athlete who has taken some time away from training and needs to build back a base level of training. The GPP typically uses parameters of training that are characteristic of the strength endurance format of training—low-intensity/high-volume resistance training. The GPP has less emphasis on the development of speed, agility, and power and more emphasis on developing an overall solid base of tennis-specific aerobic endurance and strength training to prepare the body/mind for the tennis-specific training that will follow in later phases. From a technical and tactical standpoint this phase is used to correct any major flaws in a player’s game, such as grips, game plans, and/or stroke mechanics. Depending on the needs, it may be coupled with interval training or other forms of training to initiate the individual to the training program. This type of phase may be employed with the novice or may be used as a reintroduction to a long-term training program for a high-performance athlete. It represents a reasonable method of introducing or reintroducing resistance training to an athlete. This phase usually will last 5-8 weeks. In the collegiate environment this is typically the first month or two of the fall season and is designed to acclimate the athletes back to heavy training and the volume and intensity are manipulated to accomplish this.

The following are situations where the GPP might be most appropriate for training:

The traditional periodization models would suggest that the athlete train in a general sense, not focusing on tennis-specific movements. However, these days with no true offseason, the GPP needs to incorporate more tennis related movements while still building a great general overall fitness base.

The Specific Preparatory Phase (SPP) of training defines more specific goals with respect to the training program and the tournament schedule. Usually the intensity of the training increases, with moderate to high volumes of training. Exercises must become more goal-specific with a focusing on tennis-specific strength, speed, power, and agility training. Solidifying major changes made during the GPP is also a focus of the SPP. This phase should last between 6 and 8 weeks but may be somewhat longer or shorter as necessary. This period is not where major changes are made to a player’s game. It is more appropriate for this stage to constitute the deliberate practice phase of a new skill.

The Precompetition Phase (PP) is marked by an increase in intensity and a decrease in the volume of resistance training. The skill component of training will increase with more matchplay-specific drills and training. Off-court work in the weight room and speed/agility movements will be more tennis-and competition-specific. The length of each phase varies due to several factors, especially the competitive schedule. The phase should be long enough for the athlete to adapt to the training program prescribed and not so long as to allow staleness.

Unlike many sports that have rather short competitive seasons, tennis in the junior and professional ranks involves year-round competition. The collegiate tennis schedule allows for more traditional periodization plans because of the competition phase between February-May. During a competitive phase, sometimes referred to as a maintenance phase, it is important to maintain as much strength as possible. The use of moderate intensities and moderate to low volumes of training usually occur during this time.

The major competitions for peaking are typically evident. In a collegiate environment it would be the conference and national tournaments. In juniors (depending on the level of player) it would be the regional, state, or national tournament. In the professional ranks it would be the four grand slams and possibly Davis/Fed Cup. In USTA league play it would be the end of season regional, state, or national tournament. Prior to a major competition, the athlete who desires to peak physiologically should further decrease the volume of training to promote full rest and recovery for competition.

Staired progression is a method of manipulating training intensity by systematically increasing intensities over a predetermined time-period. Staired progression attempts to initiate a physiological state known as supercompensation within the muscle tissue of the body. When a tennis player receives a training stimulus at the beginning of a microcycle that is higher than the previous load, fatigue will occur. If the same load is maintained over the period of this same microcycle during following training sessions, the body will begin to adapt to this new training intensity. This new level is referred to as a new ceiling of adaptation (1).

The unloading period should not return to initial levels of intensities; rather, it should be reduced to the level of intensity reached at the midpoint of the staired progression phase. Scheduling an unloading period allows for tissue regeneration and protein synthesis as well as the replenishment of energy stores that will have been depleted over the period of staired progression. This replenishment of energy stores during the unloading phase may exceed the previous levels attained before the training stimulus was initiated. The energy replenishment above the initial levels is commonly referred to as supercompensation, and it should leave the athlete in a heightened state of of training preparedness for another successive series of increasing training intensities (9).

A player’s technique is at the base of all development. Without a solid foundation future development will be limited. Therefore, technical work focused on stroke development and movement mechanics needs to be at the core of all good programs. Technical work is typically at its peak during non-tournament times throughout the training cycle, where competition is removed so that the learning of the skill can be the major focus. This usually takes place during the GPP and SPP. It is very difficult to make technical corrections, especially major corrections, such as a grip change, when the stress of winning or losing is also in the equation. Therefore, the coach’s role is to set up times throughout the year where technique training will be a major focus of the player’s program.

The more experienced a player, the less time is focused on technique. In younger players (6-12 year old), technique training should be a major portion of the training cycle as the next 5-10 years of the athlete’s tennis life will be directly building on the solid foundation. As the players get older, the technique aspect of training is reduced and hopefully only minor adjustments need to be made. As athletes age from 12-16 it is a time to solidify the technique and implement the concept of deliberate practice. Deliberate practice, unlike play, requires effort, and it does not offer the social and financial rewards of work (4). Five key areas of deliberate practice include (4):

Timing of technique training throughout a periodized program is essential. The athlete must not be in either a physically or psychologically fatigued state when attempting to learn a new skill (e.g., slice backhand down the line). It is important to teach new skills early in a specific period, ideally in the late stages of a recovery period or the onset of the GPP. If the coach waits until midway through the GPP, the workload (volume and intensity) in other areas (especially physical) could negatively affect the learning process of the new skill.

Tactical training is less of a priority in younger individuals (<12 years of age), as this time can be better spent developing physical and technical skills. However, once the athletes start competing at regional, state, national, and international tournaments, tactical proficiency is vitally important. Developing a player’s strategy is one area that some coaches do not spend enough time training. It is important to determine the player’s style of play and how to structure points to play into the player’s strengths and hide weaknesses. It is important to know whether the player is an aggressive baseliner who likes to dominate with the forehand or is a fast, athletic, and well-trained retriever focusing on running down every ball and physically wearing out his/her opponents. Although individual strategy is not a major focus of this chapter, it is important for coaches and athletes to have a player’s style and strategy instilled from a young age, and all physical and mental training should be aimed at optimizing this style of play. A serve and volley player should have a very different speed and agility program than a claycourt baseliner. The serve and volley player will focus on linear speed with explosive split step movements followed by short explosive lateral moves. These movements simulate what is experienced when an athlete moves from the baseline to the net and then attacks volleys. A claycourt baseliner will spend more time on lateral movement and recovery from strokes. Training of all components must fit with the performance goals and tactical style of the individual player.

The physical components of training have had the greatest amount of scientific research and practical implementation of periodization principles. The major physical components that should be periodized include linear, lateral and multidirectional speed, absolute strength, strength endurance, maximal power, power endurance, muscle hypertrophy, flexibility, and agility. The art of coaching is applying science into a cohesive program that develops all variables throughout an entire macrocycle. The problem arises when coaches try to develop too many of these variables at once. This may reduce the athlete’s development by overtraining, using inappropriate volume and intensity for the different variables. Developing different performance variables requires an understanding of how these variables improve. Training for explosive speed is a predominantly neural process, meaning that the goal of training is increasing the speed of the signal from the brain to the muscle and increasing muscle firing rates. As opposed to training for speed, training for muscular endurance is predominantly a cellular process where overloading the muscle cells is the way to improve performance. Training both of these at the same time can be accomplished, but understanding the fatigue process and how these opposing processes might negatively affect each other is important.

When and where in a program to develop specific physical variables will depend on the focus of the training cycle. It is important to have a priority list for each exercise, day, week, month, and year. This list states the major and minor focus as well as the supplemental focus areas. For example, during the general preparation period the priority might be to add 3 kg of muscle mass while simultaneously develop an athlete’s linear, lateral, and multidirectional speed as measured by the 20 m sprint and the Spider Agility test. To accomplish this, an understanding of how speed impacts strength and vice versa will influence how training and recovery sessions should be organized. It will be necessary to train speed when the athlete is freshest and the neuromuscular system is not fatigued. Unlike gaining muscle (which is predominantly a cellular adaptation), speed training is aimed at causing a positive adaptation to the neuromuscular system. Therefore, to gain greatest effect, the athlete needs to perform the speed exercises at the onset of practice sessions and the strength and hypertrophy focused exercises afterward when the athlete is in a more fatigued state. As tennis requires high levels of all the physical variables, it is difficult to completely focus on one area. If an athlete was to follow a traditional linear strength training periodized program, the athlete would spend 4-6 week blocks focused on one specific emphasis, such as muscle size (hypertrophy). Tennis players do not have the luxury of this form of training, and all physical variables need to be trained somewhat simultaneously. However, a program can be devised to optimize overall gains in all areas without development in one area causing a negative consequence in another area.

Designing a periodized program for psychological development is an area that has not received much attention in the scientific literature. As with physical training, psychological training variables, such as visualization, relaxation training, goal setting, ritual development, and arousal training, cannot all be periodized and trained at once. Different times of the macrocycle require more focus on different areas. The age of the athlete also plays a major role in the psychological training of the athlete. Some skills such as on-court rituals (e.g., bouncing the ball three times before each serve) are easy to implement, but it is not so easy to consistently perform on every single serve, especially during high-pressure match situations. This type of routine requires continual practice and monitoring by both player and coach.

Nutrition, like other training variables, should be periodized depending on the psychological and physical stress endured by the athlete. During times of harder physical training, energy requirements will be higher, and as a result, a structured nutrition plan should be developed to ensure adequate calories to sustain hard training and appropriate recovery (see Chapter 4 for more in-depth information). Proper nutrition can improve immune system function, increase energy, improve speed of muscle mass development, and reduce body fat. During periods of heavy training, tennis players are susceptible to colds, viruses, and respiratory infections. Periodizing calories and types of higher calorie food during periods of harder training may assist in keeping the athlete healthy as well as improving speed of recovery following hard training sessions. This quicker recovery will allow the athlete to train harder and longer allowing for quicker improvement. Also during periods of hard training, it is recommended that athletes supplement with products such as glutamine and leucine to help in protecting immune function and reduce the possible negative consequences of hard training. Nutritional periodization before and during tournaments is also important. The athlete’s nutritional program must be structured to provide adequate nutrients in the days before, during, and after tournament play. Refer back to Chapter 4 to apply the nutrition principles in a periodized method.

Recovery has just begun to be a focus of scientific investigation. Our knowledge of recovery techniques and the affect on performance is becoming clearer. Structuring recovery sessions in a periodized program is very individualized. All tennis players require proper recovery so as not to overtrain, but what is equally important is structuring recovery to speed performance improvement. Skill development such as technique cannot be developed as quickly in a fatigued state. Also, physical training cannot continually be increased with an infinite increase in performance. Monitoring an athlete’s performance with objective markers is important in order to catch any performance decreases. Unless the tennis athlete has access to trained physiologists or a full service sports medicine laboratory that continually measures variables such as lactate levels, blood chemistry, and respiration values, more rudimentary measures must be taken. These include waking heart rate and subjective measures of perceived exertion, though these techniques may not catch that an athlete is overtraining until it is too late and performance has decreased and the likelihood of injury and illnesses has increased.

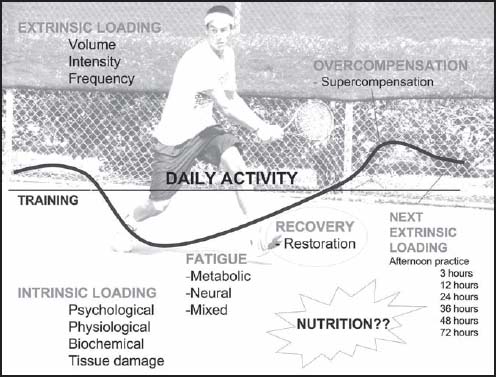

Figure 15.1: Daily recovery pattern following a training session.

One area that has not yet received appropriate attention is how a junior or collegiate athlete’s academic responsibilities and priorities play into his or her tennis career. Exam schedule, projects, and presentations take up a lot of time and do increase an athlete’s stress level. These events must be taken into account when devising programs. The challenges are vastly different for coaches who work with junior competitive players compared to collegiate coaches. When designing periodized training and competition schedules, academic landmarks such as exams, presentations, spring-break, and vacation time need to be planned into an effective program. It is important to schedule reduced training volume around exam periods or other academically time-consuming and stressful periods. To be able to get the most from the student-athletes, it is important to plan their yearly schedule with a full understanding of all the academic stressors that are likely to play a role in their development. It is more beneficial to overall development to schedule hard training weeks during light academic weeks, as the athlete will have more time and be in a less stressful mental state during these periods.

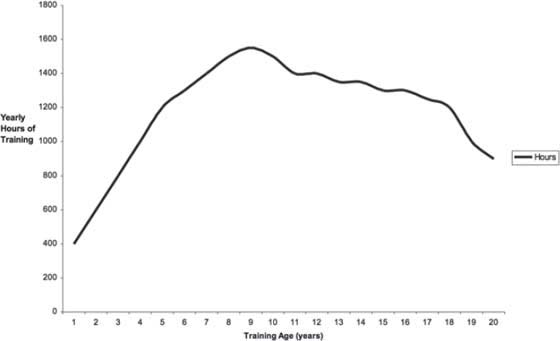

Age plays a major role in devising a periodized program. However, two different classifications of age must be defined. An athlete’s chronological age is the birth age, whereas a player’s training age is how many years an athlete has been training for tennis at a competitive level. An example would be a 16-year old male player who has been training competitively for tennis since he was 13-years old. The player’s chronological age is 16 but the training age is only 3 years. As it takes at least 10 years of training before any person can be classified as expert in a skill (4, 7), such as tennis, it requires a training age of at least 10 before a tennis player can expect to be at peak abilities and performance level. Understanding this is important for determining the number of training hours per day, week, month, and year (Figure 15.2). As each individual is different, no two programs will be the same. However, basic principles should be followed when designing and implementing the program.

Figure 15.2: Yearly hours of training over the course of a tennis career.

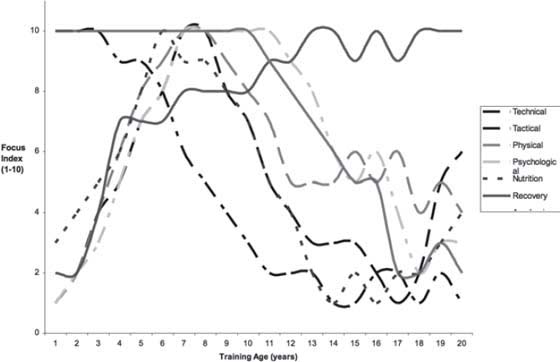

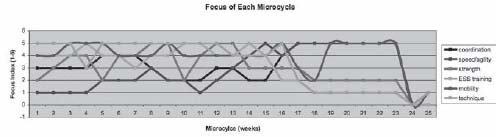

The focus Index is a term that is used to describe the amount of emphasis a certain training variable has in a cycle period. Figure 15.3 shows a long term (20 year) plan with the focus index of each of the seven periodized areas. This is an example of how you can set up a long-term periodized program with certain parts focusing on specific variables.

Figure 15.3: Career focus index for tennis.

This focus index describes a hypothetical plan for a young child who is attempting to become a professional tennis player. Creating a focus index as part of the periodized program is a big advantage as it provides a graphical representation of how the different training aspects influence each other and whether you are focusing on too many areas at one time. A focus index can be applied to single training session, training weeks, months, seasons, or years.

| CAREER LONG PERIODIZATION FOR THE TENNIS ATHLETE | |

| BEGINNING PHASE | This period is when the athlete is just learning the basics and is not focused on tournament play. |

| SKILL PHASE | The basics have been learned, and this phase is focused on developing consistency in the skills and being able to perform the skills under normal pressure situations. |

| COMPETITION PHASE | The skills are developed and now the athlete is ready to perform the skills under stressful tournament situations. Although tournaments are being played, the major focus should still be on development, with little emphasis on tournament results. |

| TOURNAMENT PHASE | This is the time for the athletes to be at their best. The years of hard practice should be paying off at this stage and results are a major focus of this phase. |

| PEAKING/MAINTENANCE PHASE | The first part of this stage is still focused on results and performing at a very high level. The second part of this phase is aimed at staying at a high level even though the athlete might be losing some of the physical gifts (i.e., speed, power, recovery abilities) or priorities have changed (family, etc.). |

Table 15.1: Career long periodization for the tennis athlete.

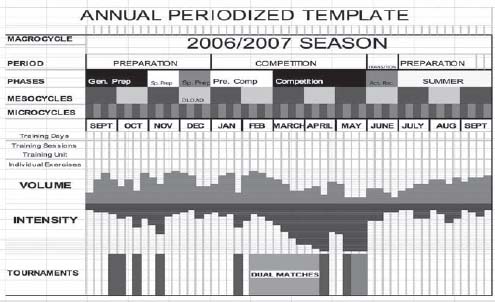

Figure 15.4: Annual sample periodized program template.

Figure 15.5: 25-week tournament focused periodized program.

Figure 15.6: 25-Week Macrocycle for an international level junior competitor focused on the physical aspects of training

Figure 15.7: 4 week competition mesocycle.

1. Bompa, T. O. Periodization of Strength. Don Mills, Ontario, Canada: Veritas Publishing, 1993

2. Bompa, T. O. Primer on Periodization. Olympic Coach. 16:4-7, 2004.

3. Derman, W., M. P. Schwellnus, M. I. Lambert, M. Emms, C. Sinclair-Smith, P. Kirby, and N. T.D. The ‘worn-out’: A clinical approach to chronic fatigue in athletes. J Sport Sci. 15:341-351, 1997.

4. Ericsson, K. A., R. T. Krampe, and C. Tesch-Romer. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol Rev. 100:363-406, 1993.

5. Fry, R. W., A. R. Morton, and D. Keast. Periodisation and the prevention of overtraining. Can J Sport Sci. 17:241-248, 1992.

6. Kraemer, W. J., K. Haekkinen, N. T. Triplett McBride, A. C. Fry, L. P. Koziris, N. A. Ratamess, J. E. Bauer, J. S. Volek, T. McConnell, R. U. Newton, S. E. Gordon, D. Cummings, J. Hauth, F. Pullo, J. M. Lynch, S. A. Mazzetti, H. G. Knuttgen, and S. J. Fleck. Physiological changes with periodized resistance training in women tennis players. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 35:157-168, 2003.

7. Simon, H. A. and W. G. Chase. Skill in chess. Am Sci. 61:394-403, 1973.

8. Stone, M. H. and H. S. O’Bryant. Weight training, a scientific approach. Minneapolis, MN: Burgess, 1987

9. Zatsiorsky, V. Science and practice of strength training. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1995