A Legend of Knockmany

HAT Irish man, woman, or child has not heard of our renowned Hibernian Hercules, the great and glorious Fin M’Coul? Not one, from Cape Clear to the Giant’s Cause way, nor from that back again to Cape Clear. And, by-the-way, speaking of the Giant’s Causeway brings me at once to the beginning of my story. Well, it So happened that Fin and his men were all working at the Causeway, in order to make a bridge across to Scotland; when Fin, who was very fond of his wife Oonagh, took it into his head that he would go home and see how the poor woman got on in his absence. So, accordingly, he pulled up a fir-tree, and, after lopping off the roots and branches, made a walking-stick of it, and set out on his way to Oonagh.

HAT Irish man, woman, or child has not heard of our renowned Hibernian Hercules, the great and glorious Fin M’Coul? Not one, from Cape Clear to the Giant’s Cause way, nor from that back again to Cape Clear. And, by-the-way, speaking of the Giant’s Causeway brings me at once to the beginning of my story. Well, it So happened that Fin and his men were all working at the Causeway, in order to make a bridge across to Scotland; when Fin, who was very fond of his wife Oonagh, took it into his head that he would go home and see how the poor woman got on in his absence. So, accordingly, he pulled up a fir-tree, and, after lopping off the roots and branches, made a walking-stick of it, and set out on his way to Oonagh.

Oonagh, or rather Fin, lived at this time on the very tip-top of Knockmany Hill, which faces a cousin of its own called Cullamore, that rises up, half-hill, half-mountain, on the opposite side.

There was at that time another giant, named Cucullin—some say he was Irish, and some say he was Scotch—but whether Scotch or Irish, sorrow doubt of it but he was a targer. No other giant of the day could stand before him; and such was his strength, that, when well vexed, he could give a stamp that shook the country about him. The fame and name of him went far and near; and nothing in the shape of a man, it was said, had any chance with him in a fight. By one blow of his fists he flattened a thunderbolt and kept it in his pocket, in the shape of a pancake, to show to all his enemies, when they were about to fight him. Undoubtedly he had given every giant in Ireland a considerable beating, barring Fin M’Coul himself; and he swore that he would never rest, night or day, winter or summer, till he would serve Fin with the same sauce, if he could catch him. However, the short and long of it was, with reverence be it spoken, that Fin heard Cucullin was coming to the Causeway to have a trial of strength with him; and he was seized with a very warm and sudden fit of affection for his wife, poor woman, leading a very lonely, uncomfortable life of it in his absence. He accordingly pulled up the fir-tree, as I said before, and having snedded it into a walking-stick, set out on his travels to see his darling Oonagh on the top of Knockmany, by the way.

In truth, the people wondered very much why it was that Fin selected such a windy spot for his dwelling-house, and they even went so far as to tell him as much.

“What can you mane, Mr. M’Coul,” said they, “by pitching your tent upon the top of Knockmany, where you never are without a breeze, day or night, winter or summer, and where you’re often forced to take your nightcap without either going to bed or turning up your little finger; ay, an’ where, besides this, there’s the sorrow’s own want of water?”

“Why,” said Fin, “ever since I was the height of a round tower, I was known to be fond of having a good prospect of my own; and where the dickens, neighbours, could I find a better spot for a good prospect than the top of Knockmany? As for water, I am sinking a pump, and, plase goodness, as soon as the Causeway’s made, I intend to finish it.”

Now, this was more of Fin’s philosophy; for the real state of the case was, that he pitched upon the top of Knockmany in order that he might be able to see Cucullin coming towards the house. All we have to say is, that if he wanted a spot from which to keep a sharp look-out—and, between ourselves, he did want it grievously—barring Slieve Croob, or Slieve Donard, or its own cousin, Culla-more, he could not find a neater or more convenient situation for it in the sweet and sagacious province of Ulster.

“God save all here!” said Fin, good-humouredly, on putting his honest face into his own door.

“Musha, Fin, avick, an’ you’re welcome home to your own Oonagh, you darlin’ bully.” Here followed a smack that is said to have made the waters of the lake at the bottom of the hill curl, as it were, with kindness and sympathy.

Fin spent two or three happy days with Oonagh, and felt himself very comfortable, considering the dread he had of Cucullin. This, however, grew upon him so much that his wife could not but perceive something lay on his mind which he kept altogether to himself. Let a woman alone, in the meantime, for ferreting or wheedling a secret out of her good man, when she wishes. Fin was a proof of this.

“It’s this Cucullin,” said he, “that’s troubling me. When the fellow gets angry, and begins to stamp, he’ll shake you a whole townland; and it’s well known that he can stop a thunderbolt, for he always carries one about him in the shape of a pancake, to show to any one that might misdoubt it.”

As he spoke, he clapped his thumb in his mouth, which he always did when he wanted to prophesy, or to know anything that happened in his absence; and the wife asked him what he did it for.

“He’s coming,” said Fin; “I see him below Dungannon.”

“Thank goodness, dear! An’ who is it, avick? Glory be to God!”

“That baste, Cucullin,” replied Fin; “and how to manage I don’t know. If I run away, I am disgraced; and I know that sooner or later I must meet him, for my thumb tells me so.”

“When will he be here?” said she.

“To-morrow, about two o’clock,” replied Fin, with a groan.

“Well, my bully, don’t be cast down,” said Oonagh; “depend on me, and maybe I’ll bring you better out of this scrape than ever you could bring yourself, by your rule o’ thumb.”

She then made a high smoke on the top of the hill, after which she put her finger in her mouth, and gave three whistles, and by that Cucullin knew he was invited to Culla-more—for this was the way that the Irish long ago gave a sign to all strangers and travellers, to let them know they were welcome to come and take share of whatever was going.

In the meantime, Fin was very melancholy, and did not know what to do, or how to act at all. Cucullin was an ugly customer to meet with; and, the idea of the “cake” aforesaid flattened the very heart within him. What chance could he have, strong and brave though he was, with a man who could, when put in a passion, walk the country into earthquakes and knock thunderbolts into pancakes? Fin knew not on what hand to turn him. Right or left—backward or forward—where to go he could form no guess whatsoever.

“Oonagh,” said he, “can you do nothing for me? Where’s all your invention? Am I to be skivered like a rabbit before your eyes, and to have my name disgraced for ever in the sight of all my tribe, and me the best man among them? How am I to fight this man-mountain—this huge cross between an earthquake and a thunderbolt?—with a pancake in his pocket that was once—”

“Be easy, Fin,” replied Oonagh; “troth, I’m ashamed of you. Keep your toe in your pump, will you? Talking of pancakes, maybe, we’ll give him as good as any he brings with him—thunderbolt or otherwise. If I don’t treat him to as smart feeding as he’s got this many a day, never trust Oonagh again. Leave him to me, and do just as I bid you.”

This relieved Fin very much; for, after all, he had great confidence in his wife, knowing, as he did, that she had got him out of many a quandary before. Oonagh then drew the nine woollen threads of different colours, which she always did to find out the best way of succeeding in any thing of importance she went about. She then platted them into three plats with three colours in each, putting one on her right arm, one round her heart, and the third round her right ankle, for then she knew that nothing could fail with her that she undertook.

Having everything now prepared, she sent round to the neighbours and borrowed one-and-twenty iron griddles, which she took and kneaded into the hearts of one-and-twenty cakes of bread, and these she baked on the fire in the usual way, setting them aside in the cupboard according as they were done. She then put down a large pot of new milk, which she made into curds and whey. Having done all this, she sat down quite contented, waiting for his arrival on the next day about two o’clock, that being the hour at which he was expected—for Fin knew as much by the sucking of his thumb. Now this was a curious property that Fin’s thumb had. In this very thing, moreover, he was very much resembled by his great foe, Cucullin; for it was well known that the huge strength he possessed all lay in the middle finger of his right hand, and that, if he happened by any mischance to lose it, he was no more, for all his bulk, than a common man.

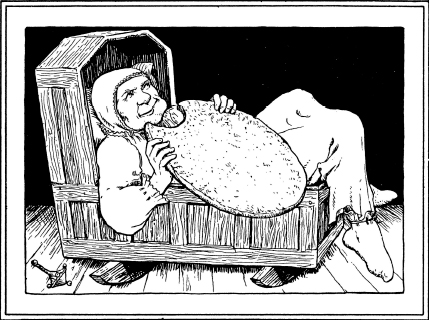

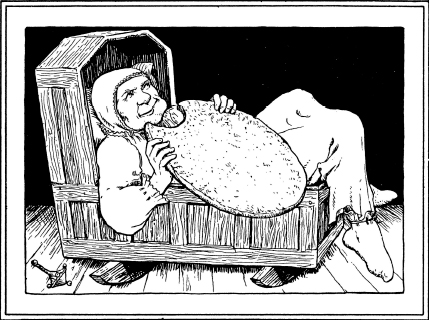

At length, the next day, Cucullin was seen coming across the valley, and Oonagh knew that it was time to commence operations. She immediately brought the cradle, and made Fin to lie down in it, and cover himself up with the clothes.

“You must pass for your own child,” said she; “so just lie there snug, and say nothing, but be guided by me.”

About two o’clock, as he had been expected, Cucullin came in. “God save all here!” said he; “is this where the great Fin M’Coul lives?”

“Indeed it is, honest man,” replied Oonagh; “God save you kindly—won’t you be sitting?”

“Thank you, ma’am,” says he, sitting down; “you’re Mrs. M’Coul, I suppose?”

“I am,” said she; “and I have no reason, I hope, to be ashamed of my husband.”

“No,” said the other, “he has the name of being the strongest and bravest man in Ireland; but for all that, there’s a man not far from you that’s very desirous of taking a shake with him. Is he at home?”

“Why, then, no,” she replied; “and if ever a man left his house in a fury, he did. It appears that some one told him of a big basthoon of a giant called Cucullin being down at the Causeway to look for him, and so he set out there to try if he could catch him. Troth, I hope, for the poor giant’s sake, he won’t meet with him, for if he does, Fin will make paste of him at once.”

“Well,” said the other, “I am Cucullin, and I have been seeking him these twelve months, but he always kept clear of me; and I will never rest night or day till I lay my hands on him.”

At this Oonagh set up a loud laugh, of great contempt, by-the-way, and looked at him as if he was only a mere handful of a man.

“Did you ever see Fin?” said she, changing her manner all at once.

“How could I?” said he; “he always took care to keep his distance.”

“I thought so,” she replied; “I judged as much; and if you take my advice, you poor-looking creature, you’ll pray night and day that you may never see him, for I tell you it will be a black day for you when you do. But, in the meantime, you perceive that the wind’s on the door, and as Fin himself is from home, maybe you’d be civil enough to turn the house, for it’s always what Fin does when he’s here.”

This was a startler even to Cucullin; but he got up, however, and after pulling the middle finger of his right hand until it cracked three times, he went outside, and getting his arms about the house, turned it as she had wished. When Fin saw this, he felt the sweat of fear oozing out through every pore of his skin; but Oonagh, depending upon her woman’s wit, felt not a whit daunted.

“Arrah, then,” said she, “as you are so civil, maybe you’d do another obliging turn for us, as Fin’s not here to do it himself. You see, after this long stretch of dry weather we’ve had, we feel very badly off for want of water. Now, Fin says there’s a fine spring-well somewhere under the rocks behind the hill here below, and it was his intention to pull them asunder; but having heard of you, he left the place in such a fury, that he never thought of it. Now, if you try to find it, troth I’d feel it a kindness.”

She then brought Cucullin down to see the place, which was then all one solid rock; and, after looking at it for some time, he cracked his right middle finger nine times, and, stooping down, tore a cleft about four hundred feet deep, and a quarter of a mile in length, which has since been christened by the name of Lumford’s Glen.

“You’ll now come in,” said she, “and eat a bit of such humble fare as we can give you. Fin, even although he and you are enemies, would scorn not to treat you kindly in his own house; and, indeed, if I didn’t do it even in his absence, he would not be pleased with me.”

She accordingly brought him in, and placing half-a-dozen of the cakes we spoke of before him, together with a can or two of butter, a side of boiled bacon, and a stack of cabbage, she desired him to help himself—for this, be it known, was long before the invention of potatoes. Cucullin put one of the cakes in his mouth to take a huge whack out of it, when he made a thundering noise, something between a growl and a yell. “Blood and fury!” he shouted; “how is this? Here are two of my teeth out! What kind of bread this is you gave me.”

“What’s the matter?” said Oonagh coolly.

“Matter!” shouted the other again; “why, here are the two best teeth in my head gone.”

“Why,” said she, “that’s Fin’s bread—the only bread he ever eats when at home; but, indeed, I forgot to tell you that nobody can eat it but himself, and that child in the cradle there. I thought, however, that, as you were reported to be rather a stout little fellow of your size, you might be able to manage it, and I did not wish to affront a man that thinks himself able to fight Fin. Here’s another cake—maybe it’s not so hard as that.”

Cucullin at the moment was not only hungry, but ravenous, so he accordingly made a fresh set at the second cake, and immediately another yell was heard twice as loud as the first. “Thunder and gibbets!” he roared, “take your bread out of this, or I will not have a tooth in my head; there’s another pair of them gone!”

“Well, honest man,” replied Oonagh, “if you’re not able to eat the bread, say so quietly, and don’t be wakening the child in the cradle there. There, now, he’s awake upon me.”

Fin now gave a skirl that startled the giant, as coming from such a youngster as he was supposed to be. “Mother” said he, “I’m hungry—get me something to eat.” Oonagh went over, and putting into his hand a cake that had no griddle in it, Fin, whose appetite in the meantime had been sharpened by seeing eating going forward, soon swallowed it. Cucullin was thunderstruck, and secretly thanked his stars that he had the good fortune to miss meeting Fin, for, as he said to himself, “I’d have no chance with a man who could eat such bread as that, which even his son that’s but in his cradle can munch before my eyes.”

“I’d like to take a glimpse at the lad in the cradle,” said he to Oonagh; “for I can tell you that the infant who can manage that nutriment is no joke to look at, or to feed of a scarce summer.”

“With all the veins of my heart,” replied Oonagh; “get up, acushla, and show this decent little man something that won’t be unworthy of your father, Fin M’Coul.”

Fin, who was dressed for the occasion as much like a boy as possible, got up, and bringing Cucullin out, “Are you strong?” said he.

“Thunder an’ ounds!” exclaimed the other, “what a voice in so small a chap!”

“Are you strong?” said Fin again; “are you able to squeeze water out of that white stone?” he asked, putting one into Cucullin’s hand. The latter squeezed and squeezed the stone, but in vain.

“Ah, you’re a poor creature!” said Fin. “You a giant! Give me the stone here, and when I’ll show what Fin’s little son can do, you may then judge of what my daddy himself is.”

Fin then took the stone, and exchanging it for the curds, he squeezed the latter until the whey, as clear as water, oozed out in a little shower from his hand.

“I’ll now go in,” said he, “to my cradle; for I scorn to lose my time with any one that’s not able to eat my daddy’s bread, or squeeze water out of a stone. Bedad, you had better be off out of this before he comes back; for if he catches you, it’s in flummery he’d have you in two minutes.”

Cucullin, seeing what he had seen, was of the same opinion himself; his knees knocked together with the terror of Fin’s return, and he accordingly hastened to bid Oonagh farewell, and to assure her, that from that day out, he never wished to hear of, much less to see, her husband. “I admit fairly that I’m not a match for him,” said he, “strong as I am; tell him I will avoid him as I would the plague, and that I will make myself scarce in this part of the country while I live.”

Fin, in the meantime, had gone into the cradle, where he lay very quietly, his heart at his mouth with delight that Cucullin was about to take his departure, without discovering the tricks that had been played off on him.

“It’s well for you,” said Oonagh, “that he doesn’t happen to be here, for it’s nothing but hawk’s meat he’d make of you.”

“I know that,” says Cucullin; “divil a thing else he’d make of me; but before I go, will you let me feel what kind of teeth Fin’s lad has got that can eat griddle-bread like that?”

“With all pleasure in life,” said she; “only, as they’re far back in his head, you must put your finger a good way in.”

Cucullin was surprised to find such a powerful set of grinders in one so young; but he was still much more so on finding, when he took his hand from Fin’s mouth, that he had left the very finger upon which his whole strength depended, behind him. He gave one loud groan, and fell down at once with terror and weakness. This was all Fin wanted, who now knew that his most powerful and bitterest enemy was at his mercy. He started out of the cradle, and in a few minutes the great Cucullin, that was for such a length of time the terror of him and all his followers, lay a corpse before him. Thus did Fin, through the wit and invention of Oonagh, his wife, succeed in overcoming his enemy by cunning, which he never could have done by force.

HAT Irish man, woman, or child has not heard of our renowned Hibernian Hercules, the great and glorious Fin M’Coul? Not one, from Cape Clear to the Giant’s Cause way, nor from that back again to Cape Clear. And, by-the-way, speaking of the Giant’s Causeway brings me at once to the beginning of my story. Well, it So happened that Fin and his men were all working at the Causeway, in order to make a bridge across to Scotland; when Fin, who was very fond of his wife Oonagh, took it into his head that he would go home and see how the poor woman got on in his absence. So, accordingly, he pulled up a fir-tree, and, after lopping off the roots and branches, made a walking-stick of it, and set out on his way to Oonagh.

HAT Irish man, woman, or child has not heard of our renowned Hibernian Hercules, the great and glorious Fin M’Coul? Not one, from Cape Clear to the Giant’s Cause way, nor from that back again to Cape Clear. And, by-the-way, speaking of the Giant’s Causeway brings me at once to the beginning of my story. Well, it So happened that Fin and his men were all working at the Causeway, in order to make a bridge across to Scotland; when Fin, who was very fond of his wife Oonagh, took it into his head that he would go home and see how the poor woman got on in his absence. So, accordingly, he pulled up a fir-tree, and, after lopping off the roots and branches, made a walking-stick of it, and set out on his way to Oonagh.