On 29 May, the paratroopers entered Heraklion at last – accomplishing their mission and bringing to an end the battle in the Heraklion sector. The men who had fought so hard to capture the town were now surrounded by scenes of devastation.

Dr Günther Müller was assigned the task of collecting and evacuating the wounded. He described the route from the airfield to the town and then to Knossos, where a British field hospital full of Allied and German wounded was found:

[...] For the first time I drive towards the city. The road is full of barricades and obstacles constructed from rocks and sandbags. I manoeuvre between the barricades. The town can be seen from on a hill, far off. The road goes over an old bridge which I cross, fearing its probable collapse, then I continue on the dirt road which climbs steeply up the hill; we see water flowing, most probably coming from the town’s broken main water pipe. We see Heraklion very clearly from the hill. High fortress-like walls surround the centre of the town. The gates look as if they were built in the Middle Ages. To the north, the port’s long mole extends out to the sea. Through winding, narrow streets we reach a big square. Everything looks devastated. Blocks of houses have been demolished and the debris is stacked in big piles on the road. It is impossible to drive the truck through it all. I manoeuvre and try to find another passage. The same scenes of devastation prevail here as well. Huge bomb craters, demolished buildings, broken electricity poles, beds and furniture – all these create unbelievable mess and confusion. The town looks deserted. Only dogs and cats are wandering around. Each time a plane passes over, they run to take cover. The bombing must have been terrible. Our doctor sees a policeman and stops him. It takes a long time to try unsuccessfully to explain to the policeman what we want and he finally understood only when a medic showed him the red cross on his armband. The policeman then jumped onto the truck and led us to a field hospital which had been the residence of an English lord.1 It was surrounded by palm and olive trees and other nearby buildings. German, English and Greek wounded are lying in tents and on stretchers.2

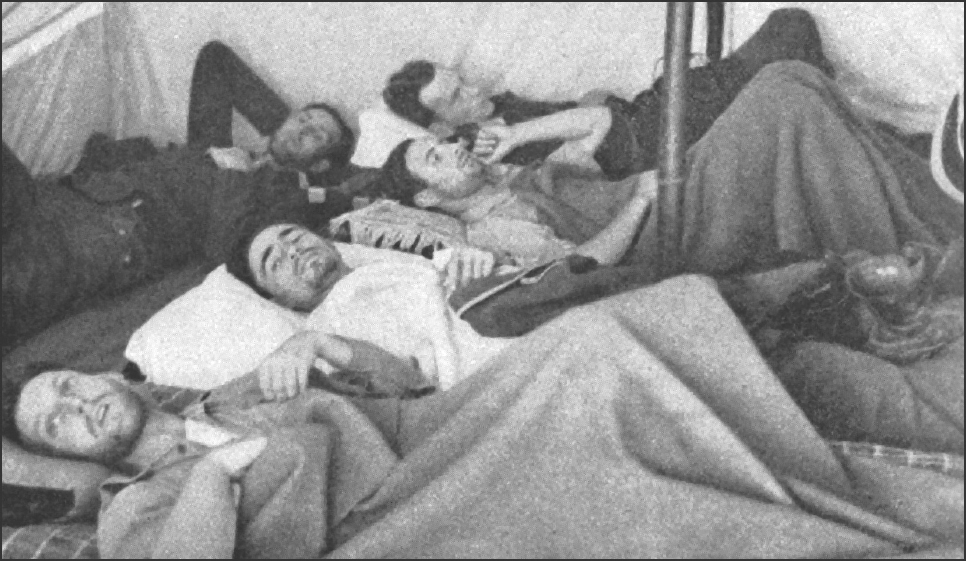

Wounded paratroopers lying in a tent at the British field hospital, situated in the yard of Villa Ariadne in Knossos. (G. Müller & F. Scheuering, Sprung über Kreta)

The residence of Sir Arthur Evans, also known as ‘Villa Ariadne’, as it is today. (Author’s collection)

The building which housed the British field hospital in the yard of Villa Ariadne. (Author’s collection)

More than 70 years after the battle, remains from the field hospital are still discovered in the yard of Villa Ariadne. (Author’s collection)

The condition of the town, as described by Dr Günther Müller, is vividly depicted in the photographs that he took on his journey.

Platia Strata, which was Heraklion’s main street (now called Kalokairinou Street), bombed and devastated. (G. Müller & F. Scheuering, Sprung über Kreta)

The same place in Kalokairinou Street today. (Author’s collection)

Apostolos Zeimbekis, a young resident of Heraklion during the battle, recalled:

During the morning of 29 May, after I left Makasi3 with a soldier from Chania who had taken off his uniform and was in civilian clothes, we went outside the town walls. We walked along the walls and after walking through the fields we entered Heraklion through Kainourgia Porta [South Gate]. There a bomb had hit the side of the wall and a man had been killed. It was the first time in my life that I had seen a dead man. We reached Valide Tzami through Evans Street and then walked down Market Street to Liontaria [Lion] Square.

From the middle of Market Street and beyond, as far as Meintani, 4 German paratroopers were sitting on the pavements on both sides of the street and resting after the battle. One of the paratroopers called to the soldier who was with me and asked for his sunglasses which the paratrooper took and put on.

As soon as we arrived at the end of Market Street, at the opposite corner right in front of the Grifizas Building, we saw a small group of paratroopers sitting on the pavement. They had a small gun with them, its barrel pointing towards Kalokairinou Street.

We moved further to Katehaki Street where just before the corner of Katehaki and Loukareos Streets was a destroyed shoe shop. We got into the shop and each of us took a very nice pair of shoes. I remember that on the shop this sign was written: ‘Saloustros’.5

The devastation in the centre of the town. (Author’s collection)

Paratroopers from the III./FschJgRgt.1 and II./FschJgRgt.2 sitting near the corner of 25th of August and Kalokairinou Streets, exactly as A. Zeimbekis describes. Some of the paratroopers wear hats and sunglasses taken from deserted shops in the town centre. (Courtesy of Shaun Winkler)

Soon after the seizure of Heraklion – and exhausted from the continuous fighting – paratroopers rest at the corner of Kalokairinou and 25th of August Streets in the centre of town. At the far left in the background is ‘Liontaria’ Square, while on the right is an anti-tank gun of the 14./FschJgRgt.1 pointing towards Kalokairinou Street, exactly as described by A. Zeimbekis. (Courtesy of Dimitris Skartsilakis)

The same spot today. (Author’s collection)

The same scene, in a picture taken from a rooftop. (Author’s collection)

Dr Alfred Eiben, a stabsartz from FschJgRgt.1, described his entry into the town on 29 May:

[…] We are heading to the Greek Hospital.6 It is difficult to find because most of the streets are blocked by debris from the bombing. At the hospital we discover about 40 wounded para-troopers and they are really happy to see us. They have spent some terrible days there. The hospital suffered a lot from the bombing. I found once again Oberleutnant Fischer who I was not able to evacuate from the town some days ago.7 The wounded have been treated extremely well by an old Greek doctor8 and his German wife. We now can promise our comrades that they will be transferred to a better hospital on the mainland of Greece where they will have the best treatment.9

Greek doctor Alexandros Stefanidis, who cared for the wounded in Pananion Hospital during the battle, described the last day of the battle:

During the night of 28 to 29 May, surprisingly we didn’t hear any bombing and a strange calm prevailed in the deserted town. Four doctors, Nicolaos Chasapes with his German wife, Frangisk, Stylianos Miliaras who was the Director of the Hospital, Emmanuel Chatzidakis, and I, felt compassion for the badly wounded, among them many Germans, so we stayed in the hospital with them despite being unable to do much to help them since the hospital had been devastated by the bombing.

So we spent a relatively calm night. In the morning Director Stylianos Miliaras was informed that the town had been occupied by the Germans. He called us to his office in order to meet the Germans who were coming to see their wounded. As we looked from the windows of the hospital we soon saw that the German flag had been raised on the highest point of the Agios Minas Cathedral, next to the cross.

You can imagine how moved we were to realise that the occupation of our homeland, Crete, had begun despite the resistance of the Cretan people.

Stabsartz Alfred Eiben. (Author’s collection)

After a while German officers appeared holding flowers in their hands and they immediately asked to see the wounded paratroopers whom they embraced and gave flowers. When the wounded men saw their comrades they cheered up and those who could immediately put on their uniforms. Their attitude changed since they were victorious at last; they lost the miserable expressions they had displayed previously, as defeated prisoners.

A very tall German officer, named Christian, was the senior doctor. He entered the hospital director’s office and asked in a rather arrogant manner for the hospital doctors to be presented to him. He then sat in the director’s chair and immediately asked the German-speaking Doctor Chasapes to assume the hospital director’s duties, as well as the duties of the Medical Director for Heraklion district. He would have [the] German title of Stadt-Artz. At the same time he ordered all Heraklion’s doctors to be presented to him within the next two days. He then said that he was very satisfied with the treatment that the doctors provided to him and to the rest of the wounded Germans. He asked Chasapes to send a letter to the Greek Ministry, reporting that the doctors in the hospital had done much more than their duty dictated. He shook our hands while maintaining the strict expression of a conqueror and then he left.10

It was a miracle that the Agios Minas Cathedral had avoided complete destruction, despite the heavy Luftwaffe bombardment.

E. Malagardis described the scene around the cathedral on 2 June 1941 and relates a strange story – the like of which can only occur during a war:

I crossed Kalokairinou Street and reached the Agios Minas Cathedral. This very big church was standing virtually intact with only a few windows broken. A bomb had exploded in the yard, close to the southwest corner of the church, leaving only a small crater. Another very big bomb, unexploded, was lying next to the northwest corner of the church less than a metre from the wall. This would have been a 250 kg or larger bomb.

The Pananion Hospital before the war. (Author’s collection)

The deserted Pananion Hospital today. (Author’s collection)

I saw the verger and asked him if the church had suffered serious damage. He answered that Agios Minas [Saint Minas] had performed another miracle and that was why there was almost no damage. I asked him again what he meant exactly and he told me to ask the church-warden, who was standing at the entrance. The church-warden explained that straight after the end of the battle, a German Luftwaffe officer had come to the church and was asking about the history of the church and the Saint. When he was asked why he was so interested in such information, he answered that the church was in the sector of the town that he had bombed and that every time he tried to drop his bombs in this area, his hands shook and he couldn’t pull the handle and release the bombs at the right moment. This he considered was due to the intervention of the Saint.11

The area around the cathedral, with buildings devastated by the bombing. (Courtesy of Shaun Winkler)

The north side of the cathedral, next to which the big unexploded bomb had landed. At this exact spot, a model of the bomb has been placed to commemorate the incident and the bombardment of the church. (Author’s collection)

Photographs of the town straight after the battle, as well as German accounts, confirm the magnitude of the devastation. Most of the residents fled to the countryside and the nearby villages, while those who stayed in the town sheltered inside the old tunnels of the Venetian walls and fortifications.

On the morning of 29 May, the Greeks realised that the British had evacuated Heraklion. Consequently, Major General Linardakis – lacking men and supplies – decided to negotiate with the Germans and stop fighting. For this reason, Linardakis sent Major Tsagkarakis to Heraklion in order to contact the Germans and end the bombing of the town and the nearby villages. That evening, Tsagkarakis went to the 43rd Greek Infantry Regiment barracks, next to the airfield, where the German HQ had been established. He proposed a truce under the same conditions imposed on the rest of Greece. Bräuer rejected Tsagkarakis’ proposal and demanded the unconditional surrender of Greek forces – threatening a continuation of the bombing and an attack on Greek units by German forces, which would be reinforced by units from Rethymnon. Tsagkarakis asked for a halt to the bombing at least, and then returned to Major General Linardakis and briefed him on the outcome of the meeting with the Germans. Linardakis – realising that he had no other option – finally accepted the unconditional surrender and, at 2215, issued the relevant orders to all Military and Gendarmerie Commands in Heraklion and Lasithi (West Crete). Only those men guarding Italian prisoners retained their arms and positions until the handover of the Italians to the Germans.

On 31 May, Linardakis signed the surrender document and asked the Germans to assume responsibility for supplying food to the thousand Greek soldiers from mainland Greece who were still on Crete; local troops had already left their units and returned home. In the evening, Oberst Wittman’s force – accompanied by mountain troops (gebirgsjägers) – arrived in Heraklion directly from Rethymnon. They then continued their move towards Ierapetra (west) in order to join the Italians. After being defeated by the Greeks in northern Greece, Italian forces had finally conducted an amphibious landing on Crete, but only after the campaign had been won. They had not been involved in any fighting, but were well prepared for a parade and a celebration.

The end of the fighting now presented the Germans with an unpleasant duty: the collection and identification of their dead comrades, who were scattered all over the drop zones and the battlefield.

Erich Reinhardt from the 7./FschJgRgt.1 described the work:

On 29 May 1941 we saw the full extent of the tragedy that had occurred around the airfield. Hundreds of dead German paratroopers were strewn around. For the first time in my life I saw the shallow provisional graves dug in a hurry by the British, with the small legend ‘Unknown German soldier killed in action.’ Our unforgettable company commander, Oberleutnant Götte, met his end at the edge of the town.12 Perhaps he had attempted to form a pocket of resistance there. There was a disgusting stench of decomposition in the heat and for the first time I was made aware of the insanity of war. What is heroism really?13

The Germans devoted 30 May entirely to the collection and burial of the dead. Dr Günther Müller described what he witnessed:

No one was forgotten. A cross in the shape of the Iron Cross along with the helmet of the dead was placed on each grave, which was marked with stones around the small hump of the grave.

To honour all the dead in the area of the fiercest fighting, a hole was drilled in the rock and a cross, made from a ship’s mast and 12 metres high, was placed. It looks away over the valley and the hills as far as the sea. Everywhere there are dead comrades. When the sun sets the inscription on the cross shines on the Cretan landscape: ‘DEN TOTEN KAMERADEN I FALLSCHIRMJÄGER RGT. 1, 20-29 MAI 1941’. (‘For the Dead Comrades – I Fallschirmjäger Regiment 1, 20-29 May 1941’.)14

The large cross which was placed on the top of Agios Ioannis Hill (East Hill) as a memorial to the dead of the 1st Fallschirmjäger Regiment. (Courtesy of Dimitris Skartsilakis)

The same spot today, with the cross removed. (Author’s collection)

The foundations of the large cross, with the hole still visible on the ground. (Author’s collection)

The initial makeshift grave of Oberleutnant Wolfgang Graf von Blücher at the exact spot where he was killed, as it was in 1941 (left), and one of the stones that was placed around the grave (right), as it was found at the same spot in 2013 (marked on the original picture with a circle). (Author’s collection and archive)

Items found at Wolfgang Graf von Blücher’s first grave on the battlefield (right). Among them are shards of pottery which were placed at the base of the cross, as are visible in the period picture (left). Another interesting discovery from the grave is a screw, which most probably came from the British wooden ammunition crate that was used to construct the first cross placed on the grave. (Author’s collection and archive)

The dead paratroopers remained buried in their makeshift graves on the battlefield for more than a year until the German war cemetery was built in Atsalenios, south of Heraklion. On the southern side of the cemetery, an imposing memorial – decorated with a fallschirmjäger eagle – was erected and wreath-laying ceremonies took place there during the period of the German occupation of the island. On each grave was a cross, on which rested a helmet.

General Bruno Bräuer, then commandant of the island of Crete, during a wreath-laying ceremony at the memorial in the cemetery in 1943. (Courtesy of Adrian Nisbett)

The graves of Wolfgang and Hans Joachim von Blücher at the cemetery. (Courtesy of Shaun Winkler)

A close-up view of some of the graves at the Heraklion War Cemetery. (Courtesy of Shaun Winkler)

The dead were exhumed during 1959-1960 and the remains collected in plastic boxes. These were stored at the Asy Gonia Monastery, near Rethymnon, before finally being transferred to and buried at the Maleme War Cemetery. The location of the Heraklion War Cemetery is now the local Atsalenios club’s football pitch.

Stefanos Kypriotakis, who is a local resident, recalled the old cemetery:

I remember that I used to climb on this huge memorial, which was made of stone, and there was an eagle depicted on it. This memorial disappeared when the dead were exhumed from the cemetery, but I do not know what exactly happened15 to it. During the exhumation of the dead, in 1959-1960, I remember that all the personal belongings [of the dead] like cigarette cases, wallets and other items were collected and gathered by the German authorities, while other items were left in the graves. I remember that we found gravity knifes, bayonets, cartridges and lots of other things. The dead were buried exactly as they were found on the battlefield – wearing their uniforms and their field gear – and in many cases, were buried with their weapons. I remember that my uncle had gathered many helmets and weapons in his backyard, and what was really strange was that live ammunition and even hand grenades were found with the dead when they were exhumed 20 years after the battle. Everything that they had been carrying with them when they were killed was left in their pockets and in their gear. Many Luger pistols were also found in the graves. At the entrance to the cemetery was a gate made of stone and there – in a glass bottle – were stored the plans of the cemetery. Using those plans, the Germans were able to identify each grave, since most of the wooden crosses had been destroyed during 20 years since the battle. It was really a pity for those young men, most of them aged 19 or 20, to meet such an end, but that’s how war is.16

The German war cemetery in the Atsalenios area of Heraklion during the war. (Courtesy of Rolf Marcus: www.kreta-wiki.de/wiki/Photos_von_Rolf_Marcus)

The cemetery in Atsalenios in 1960, during the exhumation and transfer of the remains. In the years after the war, the cemetery was not maintained and the wooden crosses gradually disintegrated. Even the stones paving the main avenue were used by the locals for building the surrounding roads. The helmets that were left on the graves were later collected and scrapped or buried. (BDF e.v. Archiv, Freiburg/Breisgau)

Gravity knives (kappmesser), cartridges and a K-98 rifle that were found at the cemetery during the exhumation of the remains in 1960. The rocks are also from the cemetery and the memorial. (Author’s collection)

As seen in this picture taken in the 1960s, rocks and other construction materials from the cemetery were used by the locals to build fences and other structures. (Author’s collection)

The same fence today, where identifiable stones from the cemetery are still present. (Author’s collection)

Greek prisoners after the battle, at the barracks of the 43rd Greek Infantry Regiment, next to the airfield. (Courtesy of Shaun Winkler)

On 31 May, the captured Greek units were transferred to Peza, where they remained until 1 July. Two Greek companies were later moved to Heraklion, while the remaining Greek units were transferred to Messara (in the middle of the island). Most of the Greek officers stayed in Peza, from where on 9 June they were transferred by car to POW camps (formerly children’s summer camps) in Maleme and Chania. Between June and November, Greek officers and soldiers were gradually discharged and transported to the Greek mainland.

Lieutenant Colonel Antonios Beteinakis wrote in his diary:

29/5–8/6/1941: Throughout these days after the armistice we remained in captivity in Archanes, where I had the opportunity to look after my farm and my fields. Two German companies occupied Archanes and settled in at the primary school building and in the nearby houses.

9/6/41: All 41 officers were transferred by car to Chania. We marched for three hours all the way from Souda to Galatas carrying our belongings on our shoulders, as did the General17 himself. At around 23:00 on 9-6-41 we arrived at the Children’s Summer Camp at the beach near Galatas where we passed the night in a field. Our condition was pitiable.

10/6/41: We were transferred to the Greek POW camp where we settled into tents. Seven officers were accommodated in the General’s tent: General Linardakis, Lt. Colonel Beteinakis, Major Tsagkarakis, Major Doulbiotis, Major Kountakis, Captain Kindylakis, Captain Kisonas. The food was very limited. We received a very small amount of bread and food, just enough to stay alive and survive in this hell-hole of captivity. It would not have been possible to survive had I not brought some bread and cheese with me from my home in Archanes [...]

13-6-41: [...] The German authorities are really angry with the Cretan soldiers and officers, suggesting that we had not acted according to convention in fighting against our country’s enemy. Some incidents of mistreatment of Germans by Greeks, had nothing to do with regular army personnel. I know this for sure since no such incident committed by soldiers came to my knowledge. I’m very proud to say that despite the fact that many of my friends and relatives were killed during the battle, both officers and soldiers, and despite incidents of mistreatment of civilians by German soldiers that I saw, I provided medical treatment to the enemy wounded and prisoners. I am confident that I fought with bravery and loyalty for my country, behaving as a civilised human being towards my enemies. Fighting with bravery and respecting the rights of enemy prisoners is characteristic of brave souls [...]

27-9-41: Today we arrived at Piraeus after a three day trip by ship from Souda. We were transferred to the POW camp at Kokkinia where we were released from captivity. I went to Athens where I received also my salary for September.18

Among the prisoners who were transferred to the former summer camps in Chania was Lieutenant Theodoros Kallinos:

[…] When I arrived at the camp, my main goal was to find a way to escape. I became friendly with a Greek doctor who was going to Chania twice a week and he began taking me with him as an assistant.

In Chania I tried to link up with people who could help me flee from the island, but my efforts were in vain. One day the Germans asked the prisoners to state if they were students. Thinking that fortune aids those who dare, I decided to state that I was a student. Along with my friends, Diamantidis and Giannoudis, we left Souda by ship and after a two-day journey we arrived in Piraeus [Athens] on 16 August 1941. I then went to my family in Tyrnavos and later I was accepted into the Mechanical Engineering Department of the Polytechnic University of Athens. There I was able to join the national Resistance and I abandoned my studies and left for the mountains to fight against the Germans.19

The paratroopers also returned to their camps in Germany, where they were welcomed as heroes with parades and celebrations. Most of them took leave in order to rest and visit their families, but the return was not pleasant for all of them.

Gerhard Broder describes:

We fly back to Greece where Hauptfeldwebel Vogler is again in command and we continue to Salonika. After a seven day trip by train we arrive in Stendal. On 25 June 1941 I write to my mother: “We have just arrived a few hours ago by train from Salonika. Unfortunately I couldn’t find a post office until now. I will not be at all happy until I have news of Heini (my younger brother who jumped in the Maleme sector). Tonight we will sleep on a bed for the first time in eight weeks. If you find an opportunity to send a letter, write to the following address: R. Jacob, Stendal, Priesterstr. 9.”

My worries are confirmed. My only brother jumped over Maleme on the morning of 20 May. Dr. Weitzel informs me that he is dead. He has personally written a letter to inform us but the news doesn’t end with the usual greetings. Besides my great sadness, the fact that my brother was killed right after the jump on 20 May depresses me terribly. I do not believe a word about his death having occurred during an attack on enemy trenches. No, the unit was shot at during landing and never had a chance to fight. They could not even retrieve their weapons. The men were buried exactly where they were killed. On the picture of his grave I see no evidence of digging but only a loose stone cover. He must have bled to death along with many of his comrades. The doctor begins his letter with the words: “Since all officers are dead...” I understand that their participation in the battle was no more than a defenceless parachute descent into an orgy of gunfire. Was that necessary? I’m critical. An analytical and sceptical train of thought runs deep in me.

The makeshift grave of Oberjäger H. Broder on the battlefield. (Courtesy of Gerhard Broder)

At home I find my mother in unspeakable misery and abysmal grief. This grief is deepened even more by her son’s farewell letter. Full of forebodings of death, he speaks with enthusiasm and devotion for the motherland: “I write this letter with the hope that it will never reach you. If it does then try to be strong and calm because in that way you will honour the dead appropriately…We know that death stands behind us. Be proud of us. I thank you for my wonderful childhood. I had a beautiful life and I had a beautiful death also…”

Only at his signature did I see expressed all the sadness of a young man: “Dear, dear mother! Your Heini.”20

Paratrooper Ernst H. Simon from the 13./FschJgRgt.1 told of his experiences after the fighting:

The next few days after the battle pass with the digging of graves for fallen comrades of our company and with normal service routine at the airfield, where the Ju-52s bring in supplies and evacuate the wounded. We have the opportunity to post a letter for the first time in two months. General Löhr and General Jeschonnek come and visit us in their white He-111.

The regiment is fully dressed in English tropical uniforms, a decision dictated by the daytime heat. In the areas vacated by the British and in often hastily destroyed catering stores we find large amounts of pristine supplies. In the ruins of the town we also find thousands of boxes of raisins. However, nobody has the appetite to eat since our stomachs have suffered quite a lot from the poor quality of the water that we drank during the days of the battle. Many cases of dysentery have already occurred.

Oberjäger Heinrich Broder (27 November 1917, Köln-20 May 1941, Maleme, Crete). (Courtesy of Gerhard Broder)

The return to Germany and the paratroopers’ parade. (Courtesy of Jose Ramon Artaza Ivañez)

On 10 June, the FjR 1 flies back to the mainland of Greece and the 13./1 Company moves to Tanagra. Almost all of us sleep during the flight. At Tanagra airfield our trucks wait, laden with sacks of mail and parcels [...]

[...] The journey via Vienna, Ostrava, Breslau and Berlin finally ends in Stendal where we arrive at dawn. We are all awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class but we also begin rehearsals for the big victory parade in the city. Since my shoulder wound is not healed yet, I do not have to participate. Our regimental commander, Oberst Bräuer makes his famous address to the regiment: “You are now going on leave. You have recovered from the battle and you should not discuss the operation too fully, which was really shit. I know that myself.”

After all this, it is now July and we go home on leave every fortnight. I visit my parents and relatives again in Polaun, Morebenstern and Reichenberg. After returning from leave I’m posted as an instructor under the command of Leutnant von Bülow and Oberfeldwebel Waide.21

Other paratroopers had to spend a long time in hospital recovering from their wounds.

Bernd Bosshammer wrote in his diary:

On 4 June 1941, at the hospital in Vienna, I found myself in a corridor waiting to be transferred to a room. I saw a nurse helping an Oberleutnant with bandages on his head and over his eyes, move towards the stairs. I recognized my company commander, Harry Herrmann. I called him and he answered: “My dear boy, Bosshammer, what has happened to you?” I told him about my condition and he promised to help me. A doctor came and took me to a room right below the room where Oberleutnant Herrmann, Leutnant Freiherr von Berlepsch and Leutnant Fischer were. They gave me a wooden pole with which to hit the ceiling in case I needed something. They put me in a new splint with special bandages. They also put over my left knee a cable hanging on a hook, the other end of which was attached to a weight to pull my leg in the right position. I stayed like that for six and a half months [...]

[…] At the hospital in Vienna Marga Baroness von Suttner visited me. She was the mother of Gefreiter von Suttner who jumped from the plane right in front of me but he was found later shot straight through the heart, probably while he was still at the door of the plane […]

Stabsartz Dr Schmidt took a lot of care with my treatment. Just before Christmas I was freed from the splint and received a leg-pelvic plaster covering my body from the foot to the breast. Harry Herrmann, Fischer and von Berlepsch had since been released from the hospital and had returned to service.22

Almost 70 years after the battle, David Hutton still had some unfinished business from his wartime service. In 1941, Corporal Hutton’s stepmother, Daisy, posted a letter which was dispatched via the Field Post Office in Egypt. Daisy was unaware that David had been wounded and captured by the Germans, and was in hospital with shrapnel peppering his body. He was held as a prisoner of war for four years, in camps in Poland and Czechoslovakia.

I was wounded and was in a hospital in Crete, then I was flown to Piraeus where the Germans removed the shrapnel, apart from the biggest piece in my arm. They took me to Germany to a military hospital. They could not have been better to me and the nurses were really nice. We then transferred to Stalag 8B and later we ended up in Czechoslovakia. I was a prisoner for four years before the Russians liberated us.23

The letter was returned to Daisy – marked ‘missing’. She put it, unopened, in a box and forgot about it. It lay there until 2011, when Mr Hutton’s sister-in-law found it while rummaging through belongings in the loft of her house in Liff, Angus.

David Hutton continues:

My brother told me he had a letter for me. It was still sealed, it had a 5d (about 2p) stamp and was initialled by my captain, Jim Ewan. Daisy used to write to me with all the family news and the letter went to Egypt, then was sent back from the Field Post Office there by Captain Ewan. When I made it back home, in 1945, it was never mentioned so I didn’t know anything about it. Daisy had all the family news in it and it was good reading it.24

When the official capitulation of the town was signed on 30 May, the battle was finally over. Heraklion had surrendered only one other time in its long history, and that was after 21 years of siege; this time, it took a mere 11 days. Once again, the town had not been taken by assault, but had surrendered, just as it had almost 300 years earlier. The fighting spirit of the defenders of the town and its surrounding areas had not been wasted, as they had achieved a military victory which was left unexploited due to the situation that evolved elsewhere on the island.

All sides fought with bravery – a fact confirmed by the high casualty rates. Now, the people of Heraklion were left to resume their lives and rebuild their town under the onus of the occupation.

1 Villa Ariadne, next to Knossos, was the residence of Sir Arthur Evans – a British archaeologist. Evans discovered and excavated the Minoan Palace of Knossos at the beginning of the 20th century. He built his residence near the site of Knossos. Later, this building was associated with other British archaeologists such as John Pendlebury and Tom Dunbabin, who during the war, became officers of the SOE and saw action in Crete. This same building was also the residence of the German commander of Crete during the German occupation of the island. It was nearby to the spot where General Kreipe was kidnapped by the Cretan Resistance (under Patrick Leigh Fermor).

2 G. Müller & F. Scheuering, Sprung über Kreta, pp.116”120.

3 ‘Makasi’ is the term for a gallery in Heraklion’s Venetian walls.

4 The centre of the town.

5 C.E. Mamalakis’ archive.

6 Pananion Hospital, near Chanioporta.

7 Oberleutnant Fischer had been left wounded in the town when the paratroopers were forced to withdraw on the evening of 21 May. Fischer was killed two years later on the Eastern Front.

8 Dr Nicolaos Chasapes.

9 C. Hatjipateras & M. Fafalios, Kriti 1941 Martyries, p.365.

10 A.G. Stefanidis, ‘Memoirs of my Life’, Athens, 1992.

11 C.E. Mamalakis’ archive.

12 The area of Katsabas - Nea Alikarnassos.

13 E. Reinhardt, ‘Memoirs of a Former German Paratrooper’, David Lenk Archive.

14 Müller & Scheuering, p.144.

15 According to accounts from other residents of the area, the memorial was demolished with explosives one night.

16 Interview with the author in Heraklion, 2014.

17 General Linardakis.

18 A. Beteinakis, Diary of Antonios Beteinakis in Captivity, Hellenic Army General Staff, Army History Directorate.

19 Interview with the author, April 2012.

20 G. Broder, Guerre Mondiale Contre Moi, p.100.

21 E.H. Simon, BDF e.v. Archiv, Freiburg/Breisgau.

22 B. Bosshammer’s war diary – BDF e.v. Archiv, Freiburg/Breisgau.

23 Interview with – and letter to – the author, November 2013.

24 Ibid.