CHAPTER 3

Age of Sharing

It is our nature to share. It is as much a part of our survival as a species as it is a central part of our self-actualization as human beings. We share because we have the enabling tools and motivation to share. When we don’t share, either we don’t have the tools or we lack sufficient motivation or safety to share. The following points are the essence of why and how we share:

- Given the right motivation (e.g., make my life easier, save me money, make me feel good as a person)

- Sense of safety (if I share information with you, nothing negative/no harm will come from it)

- Sharing enablers (with mobile phones, tablets, the Internet, wearable technology, and sensors, we have the propensity to share virtually any information with anyone)

Historical Sharing Tools

Sharing personal information is what people do as human beings. It has been the nature of human beings since the beginning of time. Until recent history, sharing was confined to physical one-to-one communication and its content was determined by the level of trust and intimacy. Communication tools evolved because human beings wanted to share more information beyond just words. Human beings’ need to share has driven prolific inventions and has historically shaped our behavior:

- 1814: First photograph

- 1829: Braille (system of reading for the blind)

- 1831: Electric telegraph

- 1835: Morse code

- 1843: First long-distance telegraph line

- 1843: First fax machine

- 1861: Pony Express established

- 1867: Typewriter invented

- 1876: Mimeograph patented

- 1876: Telephone invented

- 1876: Dewey Decimal System invented (system for classifying books in the library)

- 1876: Phonograph invented

- 1884: Fountain pen invented

- 1888: Roll film camera invented

- 1895: First radio promoted

- 1915: Mechanical pencil invented

- 1925: First television invented

- 1935: Ballpoint pen invented

- 1938: Xerography invented (process of copying paper without ink)

- 1956: Liquid Paper invented

- 1960: First cell phone invented

- 1963: Zip codes created

- 1969: First form of Internet created1

The age of sharing is driven by the ease of sharing. When contrasting the effort and competency required to use some of the predecessors of today’s communication devices (smartphones, tablets, netbooks, and laptops), we see that the ease of sharing is driving much of this new sharing age. Consider just a few years ago, when fax machines where still fairly prevalent, the time and effort required to fax a 30-page document to 200 people. Hours of time to complete this task are now measured in seconds. Other communication tools such as speech recognition are also enabling sharing to be much more natural while still being very efficient. It is not only the ease of sharing a simple item but the ability to share massive amounts of information to a broad number of entities that is transforming our world. Sharing is truly the new behavioral norm. This comes with all of the pluses and minuses of the new etiquette of sharing.

Sharing Statistics

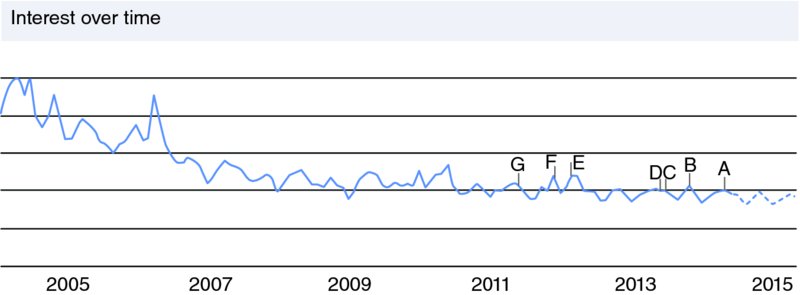

One of the most telling sharing statistics is how often individuals are searching for words related to sharing. Over the past 10 years, the word privacy as a search word has slowly declined, and it is predicted to decline even further. This is indicative of the new digital pragmatism of today’s consumer. On the surface, this may indicate that individuals are caring less about privacy issues. Individuals continue to be aware of privacy issues but are more pragmatic about their privacy awareness.

The amount of global digital information that was created and shared (e.g., documents, pictures, tweets) grew nine times in five years in 2011.2

Demographically, global averages indicated that individuals under the age of 35 (81 percent) are most likely to share any type of content on social media sites compared with individuals aged 35 to 49 (69 percent) and 50 to 64 (55 percent). Women (74 percent) edge out men (69 percent) in having shared content in the past month. Those with a high level of education (74 percent) are more likely than those with low and medium levels of education and income to share content.3

In the beginning of 2014, there was no sign that how much individuals were sharing was going to slow down. This is not to say that they do not value privacy—they do. Events such as Edward Snowden’s global surveillance disclosures and other notable organizational data breaches will help keep their new digital pragmatism in check. Here are some of the latest sharing statistics, primarily on Facebook:

- Instagram alone has 200 million users as of the beginning of 2014, with 200 billion photos shared total and 60 million photos shared daily.

- The number of Facebook users grew to 1.28 billion, with monthly active users registering at 1.23 billion. This is not a youth phenomenon.

- Forty-five percent of Internet users who are 65 years or older use Facebook.

- Sixty-two percent of Facebook users post about what they are doing, where they are, and who they are with.

- The total number of location-tagged Facebook posts is 17 billion.

- The total number of uploaded Facebook photos is 250 billion.

- The average number of photos uploaded per Facebook user is 217 photos.

- The average number of items shared by Facebook users daily is 4.75 billion items.

- The average time spent on Facebook totaled per day is 20 billion minutes.

- The average number of minutes users spent on Facebook mobile is 914 minutes compared to Facebook.com, which is 351 minutes.

- Thirty percent of Americans get their news on Facebook.4

On the surface, the declining frequency of searches on the word privacy seems to indicate a declining interest or concern with privacy. Taking this trend in the context of other privacy research, though, the exponential increase in shared personal information does not necessarily indicate that the concern for privacy is lessening. The concern for privacy is being melded into a new digital pragmatism coupled with some level of digital naïveté (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Trend of Google Searches on the Word Privacy

Source: Google Trends.

According to Intel’s “Mobile Etiquette” survey, 85 percent of U.S. adults share information online with 25 percent of U.S. adults sharing information at least once a day; 23 percent of U.S. adults experience fear of missing out (FoMo) if they are unable to share their consumer information online.

Twenty-seven percent of the respondents stated they are an “open book” both online and offline, with very little in their lives they would not share; 51 percent of U.S. adults said they would be comfortable if all of their online activity were made public tomorrow. This reflects the new digital pragmatism as well as a level of digital naïveté; that is, they do not fully understand the full life cycle of personal information.

The fact that only about half of U.S. adults would feel comfortable if all of their online activity were made public might be because 27 percent of U.S. adults admit to having a different personality online than in person, and one in five U.S. adults (19 percent) report that they have shared false information online.

Most U.S. adults (81 percent) believe that mobile manners are becoming worse (compared to 75 percent of U.S. adults surveyed a year ago), and 92 percent of U.S. adults wish people practiced better mobile etiquette in public. As a follow-up to Intel’s “Mobile Etiquette” surveys in 2009 and 2011, U.S. adults continue to report that the top three pet peeves are texting or typing while driving a car (77 percent), talking on a device loudly in a public place (64 percent), and having the volume too loud in a public place (55 percent).5

The age of sharing is across the globe, with compelling statistics on most generations’ transformation into a sharing norm. The following are sharing statistics from around the world.

Brazil

- Twenty-three percent of teens constantly share throughout the day.

- Forty-three percent of adults share sports-related information via mobile Internet-enabled devices.

- Sixty-five percent of adults say the top reason to share is to express opinions or make statements.

- Fifty-four percent share online to make new friends.

- Eighty percent of teens constantly check to see what friends are sharing.

China

- Seventy-seven percent of adults regard themselves as an “open book” online; there is little they would not share online.

- Fifty-one percent admit they share too much personal information online (i.e., sharing compulsion versus rational decision).

- Eighty-two percent of adults post or share online once a week or more.

- Thirty-one percent share throughout the day.

- Sixty-five percent of adults feel more comfortable sharing online than in person.

- Sixty-two percent of adults report that the top reason for sharing is to express opinions or make statements.

- Sixty-two percent of adults feel they are missing out if they are unable to share or consume information online (i.e., fear of missing out [FoMo]).

France

- Eighty percent of teens share online at least once a week.

- Forty-seven percent of adults share as frequently as teens.

- Forty-one percent of teens are more comfortable sharing online than in public settings.

India

- Eighty-one percent of adults share information online once a week or more.

- Forty-eight percent of adults share once a day or more.

- Sixty-four percent of adults are more comfortable sharing online than in person.

- Sixty-nine percent of teens feel they’re missing out if they are unable to share their consumer information online.

- Forty-three percent of teens try to make sure that every moment of life is captured online.

- Fifty-six percent of teens communicate with their family more online than in person.

- Sixty-seven percent of teens communicate with their friends more online than in person.

Indonesia

- Ninety-one percent of adults always feel connected with family and friends because they share online.

- Seventy-nine percent of teens always feel connected with family and friends because they share online.

- Forty-six percent of adults share online because they cannot share openly in other offline settings.

- Fifty-two percent of adults feel they are missing out if they are not able to share or consume information online.

- Sixty-eight percent of adults share information online about the moment they are currently in.

- Forty-nine percent of teens admit they share too much personal information online.

Japan

- Thirty-seven percent of adults say they feel connected to family and friends anywhere because they can connect online.

- Fifty-five percent of adults who share report they have different personalities online and in person.

- Thirty-eight percent of adults share product and service reviews and recommendations online via mobile Internet-enabled devices.

United States

- Ninety percent of adults believe they share too much personal information online (i.e., sharing compulsion versus rational decision).

- Eighty-five percent of adults share information online.

- Twenty-six percent of adults share once or more a day.

- Nineteen percent of adults admit to sharing false information online.

- Forty-two percent of teens feel they are missing out if they are unable to share or consume information online.

- Forty-two percent of teens are more comfortable sharing personal information online than in offline public environments.6

Intentional versus Incidental

Intentionally shared information is becoming increasingly more common and holds the richest and most valuable dimensions of shared information—for example, “I (consumer) feel motivated and secure about directly communicating to you (business) highly relevant information about me relative to your product or service.” Intentionally shared information is still less than 10 percent of what businesses operate on. An example would be a consumer agreeing to install an insurance company’s monitoring device into the vehicle for a potentially better insurance rate. Intentionally shared information is typically a more overt and explicit win-win proposition for both the business and the consumer. Another example would be the proliferation of mobile apps where information is exchanged for utility or reward (e.g., “I’ll reveal my location if you help me navigate to my favorite restaurant and give me a coupon”). In a perfect world, if businesses could sufficiently motivate consumers to share 100 percent of their personal knowledge, business operational effectiveness and marketing conversion rates would approach 90 percent, with cost infrastructures being reduced by as much as 70 percent.7 As enablers of sharing continue to proliferate (smarter phones, Internet of Things, smarter homes and vehicles, wearable technology, and mobile health), it will become easier to intentionally share information with businesses.

Incidentally shared information is over 95 percent of our “big data” universe and is the most available and lowest-value form of shared information—for example, “We (business) see that a ‘device’ purchased X item and also searched on three Y items on Thursday, so we think you (consumer) may also purchase Z item related to Y item sometime in the future.” Currently, 90 percent of information businesses use to predict what consumers will buy is this type of incidentally shared information.

The reality is that businesses will need both intentionally and incidentally shared information to predict accurately what and why consumers will purchase in the future. The race to the highest level of consumer relevancy will be determined by the businesses that (more quickly than their competitors) create the competencies required to motivate consumers to increase their level of intentionally volunteered information from the business’s existing mix of 90 percent incidental/10 percent intentional.

This age of sharing will accelerate this migration to balance between intentionally and incidentally shared information. Tapping into intentionally shared information is tapping into our very nature as human beings to share. The rapid proliferation of communication tools (e.g., Internet, mobile devices) will proliferate sharing further. This digital environment enables us to share almost any information with almost any audience for almost any purpose. This same digital world creates exponentially more incidentally shared information from our intentional sharing or just everyday activities that capture our lives. A major distinction between intentionally and incidentally shared information is that intentionally shared information has an intended audience and purpose whereas incidentally shared information is typically not the result of a premeditated act of intentional sharing. Understanding the difference between intentional and incidental sharing requires understanding the chain of sharing.

The chain of sharing has three dimensions:

- The “what”—what information I shared

- The “who”—the intended audience

- The “why”—the purpose for sharing

The chain of intention can be broken in any one of the three dimensions. An individual could intentionally share specific personal information with one audience and have it migrate to an unintended audience. An individual can also intentionally share specific personal information with an intended audience and the intended audience could use information for an unintended purpose. The following are example iterations of the chain of intentional sharing:

- Intentional information → Intentional audience → Intended purpose

- Example: Facebook post meant for Facebook friends who read post.

- Intentional information → Intentional audience → Unintended purpose

- Example: Facebook post meant for Facebook friends is sold to business.

- Example: Vehicle registration for local government is sold to business.

- Intentional information → Unintended audience → Unintended purpose

- Example: TripAdvisor hotel review meant for fellow travelers is leveraged by competitive hotels for cross-selling.

- Unintentional information → Unintended audience → Unintended purpose

- Example: Google product search is purchased/accessed by a business or other public organization for product marketing or organizational intelligence.

The key will be for businesses to offer an explicit and overt motivating value proposition in an environment where the consumer feels safe regarding the exchange for volunteering more revealing information.

Businesses will need to engage the consumer early and directly in the sharing intention chain with an explicit and overt motivating value proposition in exchange for more direct and relevant information. The motivating value proposition will need to be offered in an environment where the consumer feels safe about sharing increasingly revealing dimensions of buying intention and context.

Value of Intent and Context

The value of intent for a business is knowing what is inside the consumer’s head in terms of what, where, when, and how he or she will buy something in the next minute, hour, day, week, month, and year.

The value of context for a business is knowing every variable that is influencing the purchase intent both emotionally and rationally, down to subtle human nuances of decision making.

If a business had perfect knowledge of both a consumer’s intent and context, that knowledge would radically change the business’s revenue generation effectiveness (i.e., each consumer offer would generate a sale) and the business’s cost infrastructure (i.e., there would be up to 70 percent cost reduction or reallocation ranging from required associates to inventory).

Ninety percent of the data generated today by consumers is not meant to be used to predict their purchase intent or to give context to that intent. When collected and analyzed by a business, it does a relatively poor job at actually predicting intent or explaining the full context of the decision.

The higher the intent component across the shared information, audience, and purpose, the higher the value of the information both to the individual and to the business or organization leveraging or seeking to leverage the information. If a consumer is motivated and feels secure about sharing high-quality personal information with an intended audience for an intended purpose, the likelihood that the information will be highly relevant will be much greater; for example, “If you give me another 5 percent off and two-day home delivery on your high-end mountain bike with the following accessories, I will share my identity, my mountain bike purchase history, and my exact purchase criteria and will promote your product with my large mountain biking club.” If the consumer is unmotivated to share and feels insecure about sharing high-quality personal information with an unintended audience for an unintended purpose, the likelihood that the information will be relevant is much lower. For example, a consumer searches online for two weeks for a mountain bike for his wife, until his wife tells him that she doesn’t want a mountain bike anymore; the business’s analytics engage to continually serve up online ads for women’s mountain bikes for seven to 10 days after he has found out that his wife no longer wants a mountain bike.

Today, there are five realities of consumer sharing:

- More than 90 percent of the massive amounts of data created by consumers is unintentionally shared.

- Some 90 percent of information businesses use to predict consumers’ actions is unintentionally shared data.

- Accuracy from unintentionally shared data is less than 10 percent and has remained at that level for decades.

- Ninety percent of the time, consumers know their buying intent, and are now ready to share if motivated.

- Consumers’ true buying intentions reside in intentionally and discretionarily shared information.

The race to consumer relevancy will be defined by businesses that unlock the secrets of intentional and discretionary sharing of the consumer’s direct knowledge.

Science of Consumer Sharing

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s law states that the average amount of information that an individual shares doubles every year or so.

Zuckerberg’s Law of Sharing

where:

- Y is what is shared

- C is a constant

- X is time

When individuals have far more control over what they share, they share far more.

When individuals have control over what they share, their sharing explodes. Snapchat is an excellent example. Snapchat is a photo messaging application where one can take photos, record videos, add text and drawings, and send them to a controlled list of recipients with a set time limit for how long recipients can view their Snaps (one to 10 seconds). After this time, shared content is hidden from the recipients and deleted from Snapchat’s servers. At the end of 2012, there were 20 million photos shared per day on Snapchat. At the end of 2013, there were 400 million photos shared per day on Snapchat—a 20-fold increase in one year.8 In the exponentially larger platform of Facebook (in 2013 Facebook had 780 million users versus Snapchat’s 26 million users) where individuals have far less control of their photo sharing, only 350 million photos were uploaded daily.9

Why Consumers Share/Don’t Share

Studies at Harvard University’s department of psychology found that individuals devote 30 to 40 percent of their speech to informing others about their experiences. They found that individuals take advantage of opportunities to communicate their thoughts and feelings to others because the act of sharing engages neural and cognitive mechanisms associated with psychological rewards for the individual. The very act of self-disclosure is directly linked to increased activity in the brain’s reward pathways of the mesolimbic dopamine system. The research findings indicate that even simple sharing or communicating information to others induces psychological rewards for individuals. The researchers’ conclusion was that disclosing information ranging from a complex personal experience to simple information about oneself is intrinsically rewarding.10

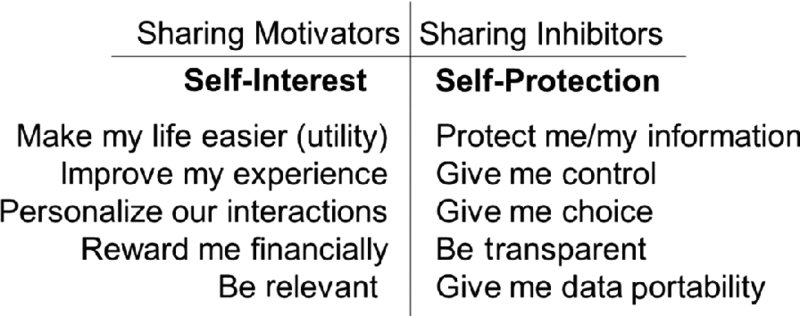

The behavioral mechanics of sharing personal information are simple. There are two primary dimensions: One is a motivator (positive) and the other is an inhibitor (negative). In this model, there is a balancing dynamic of perceived relativity. If the motivators’ side of the equation is perceived to be extremely high, the inhibitors’ side of the equation is perceived to be less important to the consumer. Conversely, if the inhibitors are extremely high, the motivators are perceived to be less important (see Figure 3.2).

(+) Sharing Motivators (I want to share because I can now do or get something)

- Self-interest

- Utility (When I share this information, I can now do this…)

- Find a restaurant, find a professional, find my size pants, help me share achievements/life with friends/family, improve my experience

- Reward (When I share this information, I can now get this…)

- Low-order

- Product, service, discount, coupon

- High-order

- Likes on Facebook, many comments from friends on my post, many followers on Twitter, many hits on YouTube

- Utility (When I share this information, I can now do this…)

(–) Sharing Inhibitors (I don’t want to share because I can’t control the bad things that may happen to me)

- Fear/anxiety

- Control and/or choice mitigates fear.11

Figure 3.2 Consumer Information Sharing Equation

Copyright JohnMcKean@InformationMasters.com.

An increasing amount of information that individuals share is volunteered on social networking sites.

Intel’s “Mobile Etiquette” survey found that a majority of U.S. adults (85 percent) share online, one-quarter of U.S. adults share at least once a day, and 23 percent of U.S. adults feel they are missing out when they haven’t shared or consumed information online.

Why Is Sharing (Self-Disclosure) Important?

Divulging personal information about ourselves stimulates regions in the brain associated with a sense of satisfaction regarding food, money, and/or sex. Eighty percent of social media posts are about the individual who is posting. Of the 250 million photos that are updated daily, 35 percent of posters tag themselves in the photos. In fact, nine out of 10 Americans believe that most people share too much personal information online. Based on this clinical sharing need, Facebook has tested whether users would pay to have their sharing highlighted. There is also a sharing gradient where individuals with higher levels of narcissism or potentially low self-esteem spend far more time on social media sites (e.g., Facebook) than those with higher self-esteem. Amazingly, 40 percent of everyday dialogue is about how we think or feel. Harvard University has conducted brain imaging and behavioral experiments that point to the neurological underpinnings of the rewards to share personal information. Bottom line: When we share, we positively stimulate brain cells and synapses. These positive stimuli are in the same category as the stimulus we get from consuming food or acquiring money. People will even sacrifice money in order to share more about themselves. The Harvard researchers found that individuals were willing to give up 17 percent to 25 percent of potential earnings (in the study) so they could reveal more personal information.12

Fear of Missing Out

Fear of missing out (FoMo) is another important human driver of sharing. Millennials and earlier generations are particularly driven by social online FoMo. It is their norm to use texting and status updates to stay in touch with friends and family far more easily than with phone calls. FoMo not only drives individuals to share and interact on social sites but also manifests behaviorally as a compulsion:

- Twenty-seven percent of individuals check social networks when they wake up, and 51 percent log in periodically throughout the day.

- Fifty-six percent believe that not regularly checking sites means they’re potentially missing out on important updates, content, or events.13

Social Validation

Social validation is different for every individual. In face-to-face interactions, social validation will come in the form of a smile or a kind word. In online interactions, it can come in the form of a Facebook like. It is a social affirmation as well as a confirmation of our existence. Skills are then developed to maximize the affirmations online.14 Some of the psychological underpinnings of FoMo emanate from our instinct to survive within our groups.

As Dr. Stephanie Rutledge explains, “We have a brain wired for collaboration, compromise, restraint, comprehending, and managing one’s place in shifting alliances.” When individuals witness other activities that are going on without them, it can trigger primal instincts of survival. These reactions can be heightened with younger generations who are still in the process of establishing their survival skills such as personal and professional identities that support an economically viable existence (i.e., surviving in the world).15 Individuals can rate their own FoMo score at www.ratemyfomo.com/.

Ego

A person’ s emotional motivation to share personal information on social networks is more tied to the audience than the generic need to connect socially with other individuals. Individuals’ focus on themselves drives them to update their status or tag themselves in photos. They are essentially trying to create a personal or professional brand when they share information on social networks such as Facebook, LinkedIn, or Twitter.16

One of the measurements of whether other people actually care about what an individual shares (i.e., social influence) is a Klout Score. Klout is a website and mobile app that ranks people according to their online social influence via the Klout Score. The Klout Score is a numerical value between 1 and 100 that measures the size of a person’s social media network and correlates the content created to measure how other people interact with their content.

Klout and American Airlines partnered to offer a promotion with two dimensions:

- Boost people’s Klout Score and redeem a prize via increased interaction with Klout.

- Earn a bonus when sharing the promotion with friends.

The prize was access to an American Airlines’ VIP lounge for those who received a Klout Score of 55 or higher.17

This is a subtle way to capitalize on driving egos to share more while promoting a particular business. Klout is leveraging this further by partnering with other major brands such as Sony, Nike, Microsoft, Disney, Audi, and Gilt to encourage individuals to boost their personal brand while simultaneously promoting commercial brands.

Social Comparison

It is natural for individuals to compare themselves to others, particularly in their peer group. It is part of our instinct to survive relative to others; that is, the most fit will survive. Individuals compare a wide range of dimensions, including physical and emotional traits (e.g., physical appearance, feelings, strengths, weaknesses, abilities, attitudes, and beliefs). In most cases, individuals compare themselves to peers or those in a similar situation. Individuals compare themselves to others who are perceived as better than they are (upward social comparison) and those who are worse off (downward social comparison). This is tied to the development and maintenance of self-esteem.18

Social Space Underpinning New Sharing Norm

The social and search organizations (e.g., Facebook and Google) have been leading the incidentally shared information evolution, with Facebook setting the pace and testing the boundaries of how much information individuals are willing to share and how much monetization they can extract. When privacy backlashes occur from individuals, governments, or advocacy groups, Facebook typically acquiesces.

The largest opportunity is in the intentionally volunteered information area. This holds the most promise for businesses that want to achieve extremely high levels of relevancy. Whereas the incidentally shared information will still need to be analyzed to create inferred buying intentions, intentionally volunteered information can be managed to generate actual buying intentions.

Social sites give individuals an opportunity for easier self-disclosure. Self-disclosure is a central component of creating and developing intimacy (e.g., friendship, love). Social sites give individuals who have a harder time with face-to-face sharing an easier road to socializing. Individuals with lower self-esteem oftentimes are hesitant to disclose personal information on an ongoing basis in intimate relationships.19

What Consumers Share

Individuals continue to make dramatic increases in their propensity and competency to share personal information via social media such as Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter. With over one billion Facebook users, 650 million of them are active daily posting some of the most intimate details of their lives, and 750 million of them are sharing their personal information via their mobile phones. These numbers grow exponentially when the numbers of friend connections multiply. Currently, there are 150 billion friend connections on Facebook. Individuals reveal their personal feelings (likes) about everything from people to products. Facebook’s likes total 1.13 trillion since its launch—4.5 billion per day. Perhaps some of the most revealing aspects of Facebook are the photos that individuals post, which many times convey far more than words. Individuals post 350 million photos a day on average to Facebook. An important trend that is occurring with Facebook is that while younger generations (Y and Z) are still sharing their personal information, they are tightening their privacy settings and regularly deleting and editing previous posts.20

Despite this propensity to share personal information, only 75 percent of Facebook users would consider clicking on a Facebook advertisement, and a full 35 percent state they would never click on a Facebook ad. The object lesson here is that using the best incidentally volunteered personal information and advanced algorithms, individuals are highly unlikely to respond to even highly targeted “push” marketing.21 From a business perspective, Generation Y’s purchasing power alone approaches $200 billion, with influence over half of all economic spending in the United States.22

This behavior indicates that they still have the propensity to share personal information but want more control over who sees it and how it is used. This indicates a discernible shared information maturation process when Generations Y and Z (Y = born 1980–2000; Z = born 2000–present) migrate from an almost complete apathy toward privacy issues to being far more attuned to the privacy controls they manage regarding their personal sharing. In a survey, 70 percent of Millennials agreed with the statement “No one should ever be allowed to have access to my personal data or web behavior,” and 77 percent of individuals over 35 agreed. Gen Yers also indicated that they are more likely to share their location in order to receive discounts than Generation Xers (Gen Yers 56 percent versus Gen Xers 42 percent). Twenty-five percent of Gen Yers indicated that they would share personal information to get more relevant advertising, versus 19 percent of Gen Xers. More broadly, over half of Millennials said they would share information with a company if they got something in return, versus 40 percent of those 35 and over.23

In another recent survey, 28,500 individuals indicated that they are willing to share personal information with their preferred retailers regarding their media usage (75 percent), demographics (73 percent), identification such as name and address (61 percent), lifestyle (59 percent), and location (56 percent) in return for sufficient utility or reward.24 Beyond just Millennials, 85 percent of cross-generational online consumers know that websites track their online shopping behavior, and they have a basic awareness that this tracking will help companies present more relevant offers and content. Seventy-five percent of online consumers are comfortable with retailers using a certain level of personal information to improve their shopping experience, and 64 percent of online consumers believe that revealing personal information will be sufficiently rewarded by the companies’ increase in offer relevancy. Conversely, 36 percent of online consumers believe that the trade-off in relinquishing their privacy is not worth the reward in added offer relevancy.25

Pew Research Center’s Internet Project revealed the three main dimensions of how and why individuals share their locations. Many individuals use their smartphones to navigate the world; 74 percent of adult smartphone owners ages 18 and older use their smartphones for directions or information about their current locations; 30 percent (up from 14 percent in 2012) of these smartphone owners also include their location in their social media posts. There is a slight decline (18 percent down to 12 percent of adult smartphone owners) in the number of smartphone owners who check in while using location services. This is likely due to the fact that the utility or reward for doing so is insufficient to compensate them for the additional location information or effort to do so. Of these geo-social service users, 30 percent check in to places on Facebook, 18 percent to Foursquare, and 14 percent to Google Plus. Overall, statistics show a steady increase in divulging location.26

Despite the growth, divulging one’s location is still cause for concern and prompts mobile users from all age groups to turn off location tracking features at some point due to privacy concerns. Forty-six percent of teen app users indicated they turned off their location tracking feature because of concerns that people or businesses would access this information.

There still is a growing trend for individuals in most generations to reveal their physical locations in order to receive some type of text alert for discounts or location-specific offers. A recent survey found that 31 percent of individuals are at least somewhat interested in receiving such texts, which was a 5 percent increase from the previous survey. In addition, 10 percent were very interested in receiving text alerts, which was an increase of 5 percent from a previous survey. Fifty-three percent of individuals view texts as a more compelling communication medium, as texts are typically more succinct, simpler, and easier to act upon than traditional ads, coupons, e-mails, and direct mail. Seventy-three percent of individuals say they are likely to visit a store after receiving a geo-targeted text message, while 71 percent actually made a retail store visit, with 61 percent making a purchase after receiving the alert.

Another interesting dynamic when individuals agree to share their locations is that their expectations increase; that is, they anticipate the special offer when in the proximity of certain stores. Combining the individual’s location data with other dynamic data such as weather, traffic, events, loyalty information, past purchases, user data, and demographics dramatically increases the offer’s relevance to the individual and thus the business’s conversion rates. Geo-fencing is also applicable not just to store-based locations but also to places that the targeted individuals are likely to frequent (e.g., sports arenas, concerts, ski resorts, airports, gyms, and parks). Also, adding an incentive to signing up for the location-based text alerts will increase the participation up to twofold.27

In a broader context, an individual’s willingness to reveal location supports the advancements in the broader geo-spatial analytics. Dr. Waldo Tobler (American-Swiss geographer and cartographer, and professor emeritus at the University of California, Santa Barbara, department of geography) theorized that “Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related to each other.” This conclusion is referred to as the first law of geography. To extend Dr. Tobler’s theory to an individual’s value of things, something that an individual intends to purchase has a certain perceived value, but near things have a higher perceived value; that is, proximity of an item defines its perceived value to an individual.

Just as the concepts of Isaac Newton’s law of universal gravitation are synonymous with the concept of spatial dependence, perceived value is spatially dependent. Individuals’ perception of value typically centers on the perception of time expenditure relative to other related activities (i.e., convenience and any associated travel costs). This is supported by the gravity model of trip distribution and the law of demand in that the probability of traveling to a location to purchase an item is inversely proportional to the cost of the travel, and therefore changes the perception of value at that location and at that point in time. To have a complete behavioral picture of the relationship between an individual and the items he or she has bought or will buy in the future, the location of each individual and each item is critical as “everything and everyone has to be somewhere.” Not only are these dimensions critical in creating a more accurate current picture, but they also help in anticipating the next event. When a business can combine operational and event-driven analytics against an individual’s location, it can create a higher value proposition for the individual and more efficiency for its operations.

Businesses can extend this value proposition to an individual by using augmented reality, where a business marries its product or service to a physical, real-world environment with relevant information based on the customer’s geographical location. As individuals are hiking with their iPhones, they point the iPhones at the mountain peak they are about to climb and get a readout on the relevant information about the ensuing hike based on their location information. The central value of augmented reality is that it is a relevant information feed in real time and in a semantic context with the individuals and their physical environment. To extend this concept, a business can also use virtual reality to simulate an individual using its product and service based on the information that the individual volunteers to the business (e.g., the mountain in front of the hiker is 12,000 feet high with dense fog, a Park Service hiking restriction is currently in place, and it will take seven hours to reach the summit based on the individual’s physical condition and history).

Another characteristic is that the individual can interact with the augmented reality intelligence and digitally manipulate the assessment. The individual points the iPhone to another peak and suggests climbing this new mountain on a clear day. The mobile app responds with the new time frame and a suggested day based on the weather forecast. So the value of the information is based not only on the location of the individual and the physical mountain but also on the individual’s process of interacting with the mountain. With the individual volunteering his or her location information and streaming intelligence, the individual evolves from a passive user of the information to a participant and co-creator of the experience.28

| Past | Now | Emerging | |

| Design paradigm | Expert driven | Human centered | Facilitated |

| Audience role | Customer | User | Participant |

| Activity |

Consume |

Experience |

Co-create |

This observation is embedded in the gravity model of trip distribution. It is also related to the law of demand, in that interactions between places are inversely proportional to the cost of travel, which is much like the probability of purchasing products that is inversely proportional to the cost.

Another interesting trend is that the nature of personal information sharing is changing for Generations Y and Z. These generations are migrating from Facebook to microblogs like Twitter and Pheed. Twitter’s demographics saw a doubling of teenagers’ use in 2012. Teenagers share their tweets more publicly on Twitter than they do their Facebook posts (i.e., public tweeting versus Facebook posts to friends only). It’s interesting to note that while social networking websites like Facebook, MySpace, and LinkedIn also have a microblog sharing feature, called “status update,” Twitter is the most popular, with 500 million users sharing 400 million tweets per day.

Texting is another information sharing practice that is more prevalent in generations Y and Z with staggering frequency. Generations Y and Z send 10 times the number of texts than older generations do. U.S. individuals with smartphones between the ages of 18 and 24 send 2,022 texts per month on average (67 texts per day), and receive an additional 1,831 texts.29 That is double the number of texts that smartphone users ages 25 to 34 send.

It is important to look at Generations Y and Z, as they are the harbingers for personal information sharing. Generationally, these individuals have also shown a tremendous growth in information sharing competency and sophistication that was unheard of a decade ago. Particularly with these generations who are information natives (i.e., born into an “informated world”), the generational effect of individuals being born into a world of computers, tablets, smartphones, and apps is raising not only innate personal information competencies but also the propensity and capability to share information. Generationally, individuals are showing more and have less sensitivity to privacy issues, particularly the later generations Y and Z. This refers to incidentally volunteered personal information. There is a high likelihood that this will also be the case for intentionally volunteered personal information given the right motivations and control.

Individuals are showing a strong willingness to share their physical locations via their smartphones’ Global Positioning System (GPS) capability. Many comprehensive location-based offerings from Foursquare, Facebook, Yelp, and increasingly Groupon have provided a steady stream of location-based opportunities for individuals. As with any mobile app, individuals must perceive the utility to relinquish their personal location. These geographically referenced social networks ask individuals to check in to various locations such as coffee shops, bars, or homes, and share their location information with other friends on the network. These location-based services provide information not only on current locations but also on future locations—that is, the individual’s next destination. This functionality operates from the GPS locator on the individual’s mobile device, allowing the social network to know where the person is. Yelp’s utility to individuals is that it is a “consumer review aggregator” that aggregates individuals’ reviews of product and service offerings. There is a growing comfort for individuals to opt in, in order to reveal their location to benefit from location-based offers by businesses.

Geo-fencing is an important dimension of how individuals receive the utility in return for revealing their location (e.g., an individual caught in a rainstorm receiving a special on umbrellas that is within a five-mile radius). The geo-fence is a dynamically generated radius, reference point, or boundary of the individual as the individual changes locations—for example, radius around one’s home, radius around a store, radius around the seat of an automobile (a specific point), a school zone (notification the child is exiting the zone). When an individual enables the GPS function on his or her smartphone and has a location-based marketing (LBM) app such as ShopAlerts (Placecast), a merchant or manufacturer can communicate timely and relevant products and special promotions when the individual enters or exits the geo-fence. The use of geo-fencing is represented by a cross section of industries (e.g., retailers, manufacturers, hospitality, transportation). Top brands, including North Face, Starbucks, L’Oréal, Subway, Kohl’s, Kmart, Hewlett-Packard, JetBlue, and SC Johnson have/are using ShopAlerts programs. Ten million individuals perceive that the value they gain from Placecast’s ShopAlerts warrants revealing their location information. ShopAlerts is licensed by Telefonica O2 in Europe and AT&T and DDR in the United States and is used by millions of individuals.

Google has begun integrating an individual’s location usage of Google Maps with the individual’s Google Plus social community of friends. As the individual travels and indicates favorite locations and businesses, both the individual and the circle of friends benefit. The individual’s behavior also captures the decision process. For example, the individual travels to Los Angeles and queries Google Maps about Thai restaurants. The individual reviews the menus of three Thai restaurants on Google Maps, then briefly stops at one of the locations, and continues on to spend one hour at the final restaurant; the individual considered these three options, the second runner-up was X restaurant, and the person chose Y restaurant. Another aspect of Google is the intelligence gained at the nexus between location and search (i.e., intent).

This willingness to share personal buying information occurs when businesses have provided a clear utility and/or reward to individuals for sharing their personal information directly with the business. Some examples include My Lowe’s (planning future home improvement projects), Meredith’s My Recipes (recipes for future meals), Aviva (monitor your driving to lower your insurance premiums), and Amazon (Wish List of what the individual explicitly indicates he or she would like to buy in the future).

These examples of information sharing on social sites and microblogs are considered active sharing of personal information. This decade has seen a tremendous growth in another category of personal shared information—passive information sharing. This passive information sharing is primarily enabled by direct personal information feeds from smart objects and wearable devices (e.g., Nike smart watches, Volt electric cars, Colorado Springs Utilities self-monitoring). In passive information sharing, the individual’s personal activities stream in information flow of data to the individual and/or other external entities (e.g., running with their Nike FuelBand or Apple iWatch, driving their Volt electric car, monitoring their home’s electricity consumption). In context, a Boeing 737 engine generates 10 terabytes of data every 30 minutes, and a six-hour flight from New York to Los Angeles on a twin-engine aircraft creates 240 terabytes of data on the engines’ performance and health.30

The best examples of burgeoning subindustries that have emerged in this decade for volunteered consumer intelligence are “quantified self” (QS) (data acquisition on a person’s daily life activities), the Internet of Things (everyday smart devices that are fully integrated via the web), and mHealth (individuals monitoring their own health supported by mobile devices). Much of the activity has been centered on the explosion of mobile apps technology, which extracts volunteered buying context and future buying intent or plans directly from the individual. More detailed examples of “quantifying yourself ” and the Internet of Things will be illustrated later in the book (Chapter 7). In the subcategory of mHealth, it’s estimated that 30 percent of smartphone users have installed wellness apps. There are 500-plus mobile health projects worldwide and 40,000 medical apps available for smartphones and tablets. Twenty-nine percent of 18- to 29-year-olds research health information on their smartphones; 18 percent of 30- to 49-year-olds and 8 percent of 65+-year-olds do so.31 At the current rate, mobile health downloads are doubling each year; they are used to manage sleep, eat healthier, manage moods, track pregnancies, manage prescriptions, monitor blood pressure, check nearby pollen levels, and so on. Some 2.8 million individuals use a home monitoring service with integrated connectivity. This figure does not include individuals who use monitoring devices connected to a PC or mobile phone.32

Another subindustry of volunteered customer intelligence is professional intelligence. LinkedIn, Viadeo, and XING are some of the leading players where individuals share their personal occupational details on social networking websites to serve their professional occupation and aspirations. LinkedIn is clearly the leader in this information sharing space. LinkedIn is an important object lesson for the dynamics of an individual’s personal information sharing and what businesses need to create to compel individuals to share their personal information directly with the business. LinkedIn is a social platform for professionals. The information that the individual shares about his or her professional history and details is personal professional information regarding the individual. Some 230 million individuals of LinkedIn’s user base perceive great value in sharing their personal professional information, because there is explicit reward and/or utility. The individual has the ability to control the distribution and use of the information.

In fact, there is a fledgling industry supporting intentionally volunteered customer information, with some roots extending back to the last decade, such as project vendor relationship management (VRM). This new industry represents a new set of start-ups and emerging industry standards organizations, consortiums, work groups, and protocols that will evolve over the coming decades.

In summary, the first half of this decade has demonstrated that individuals are significantly increasing their propensity to share personal information when there is personal utility and/or reward for doing so. Individuals have also shown a clear ability to manage a more complex personal data environment as well as leverage the information capabilities of mobile and web infrastructures like no other previous decade has seen. In fact, individuals are currently a decade ahead of businesses informationally and are primed to engage directly with businesses once the business enables innovation on the individual’s behalf (demand side). Demand-side innovation will once again unlock supply-side innovation as in previous decades (e.g., data warehouses, business intelligence, and web analytics).