Last year, my friend Merry traveled cross-country to attend her father's funeral. Upon arrival, she was exhausted, emotionally distressed, and nervous. Her hands were shaking, and she could feel her heart racing; but she was determined to deliver a eulogy at the service. Just before addressing the crowd, she went into a quiet room and practiced five minutes of a simple Yoga technique called Focused Breathing. Her hands stopped shaking and she felt her pulse returning to normal. She was centered and tranquil, able to read a tribute beautifully without her voice so much as cracking. It was a remarkable illustration of just how calming the breath can be.

The breath is the most important tool in Yoga. Even when you cannot move your body—you're stuck in that big business meeting or that tiny airplane seat— you can still practice Yoga with your breath. Yoga breathing is simply using various techniques to breathe in a slow and focused manner, allowing you to concentrate on your breath and become more conscious of your body's rhythms.

The ability to affect your body's functioning through the way you breathe is recognized in many areas of modern life. When you're angry and tempted to explode verbally you're advised to “take a deep breath.” People who are experiencing acute or chronic pain are often taught specialized breathing techniques as a way of managing their pain: Women in labor use variations on Lamaze breathing; and other pain sufferers, such as those with cancer or fibromyalgia, are taught deep breathing exercises to reduce their need for narcotics. Biofeedback has been around for decades and includes instruction in deep breathing to help control physiological reactions that are ordinarily unconscious, such as heart rate and blood pressure. The martial arts use the breath as a means of keeping the body, mind, and emotions in control. Even athletes, such as Olympic swimmers and marathon runners, must consciously work on their breathing techniques to improve their physical and mental functioning.

Your body's breathing center is actually in the brainstem, where many of your autonomic functions are controlled, such as your heart rate, blood pressure, skin temperature, and digestive process. Breathing is the only autonomic function that you can control at will, kind of like a manual override. Research indicates that when you manually take control of your breathing, you are given a little bit of control over your other autonomic functions as well. Thus deep, measured Yoga breathing affects the respiratory system by increasing absorption of oxygen and release of carbon dioxide. It can calm a rapid heart rate and relax muscle tension. Yoga breathing also helps strengthen abdominal muscles and improve posture.

Probably the two most important benefits of Yoga breathing are its effectiveness in stress reduction and pain management. Since stress is an underlying factor exacerbating virtually all other health conditions, the reduction of stress through regular Yoga breathing can have a major effect on your health. Yoga breathing reduces stress by curbing the flow of adrenaline and other stress hormones. It also quiets the distractions of the mind and signals the brain to minimize perception of pain. I have witnessed literally hundreds of my clients over the years reduce or totally eliminate acute symptoms of back pain using Belly Breathing, a Yoga technique explained later in this chapter. The most phenomenal aspect of Yoga breathing is that you are in control. You can send health-enhancing Yoga breathing messages to your body any time, anywhere.

Entire textbooks have been written about the physiology of breathing; but don't worry, we're not going to go into that much detail here. To understand the Yoga approach, you need to know only a few basic things about breathing.

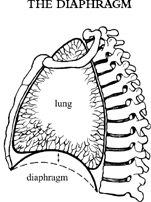

When you think of your breath, you might immediately think of the lungs, but the lungs are actually passive organs that hitch along on the breathing ride. The real force behind breathing is the respiratory musculature, driven by the diaphragm. It has been said that the diaphragm is responsible for about 75 percent of the effort of quiet breathing. I wonder how many folks have any idea where their diaphragm is or how it works.

Diaphragm literally means “partition,” aptly enough, since it divides the thorax (rib cage) above from the abdomen below. You could say that the diaphragm is the floor of the former and the roof of the latter. The lungs and heart sit right on top of the diaphragm, and the stomach and liver nestle right below it. Our diaphragm's rhythms—powered by our breathing— affect these organs, partially explaining how breathing influences so many other functions of the body.

The circumference of the diaphragm attaches to the lower rim of the rib cage, which makes it look in outline like a giant kidney bean. It also has two long skinny muscular attachments, called crura, along the sides of the lumbar vertebrae. They always remind me of a long pair of pigtails.

Each inhale is initiated when the diaphragm contracts and descends. The double dome flattens out and pushes down (only about an inch) against the abdominal contents, which have nowhere to go but out. I'm sure you have noticed how your belly puffs every time you inhale. That puffing, which allows the easy descent of the diaphragm, is made possible by the relaxation of the rectus abdominis, a muscle that runs in a flat sheet between your pubic bone below and the bottom of the sternum above.

The contraction and descent of the diaphragm (assisted by a few sidekick respiratory muscles) increases the volume of the thorax, lowering its pressure relative to the outside world. Just like wind is caused by air flowing from areas of high pressure to areas of low pressure, fresh air from the outside rushes into the thorax, and voilà!—you inhale. Then on the exhale, this whole thing gets reversed. The diaphragm slowly relaxes and returns to its dome shape, egged on by the contraction of the rectus, which pushes back and up against the abdominal contents. This decreases the volume of the thorax and the inhaled air, now full of carbon dioxide and other waste stuff we no longer need, is forced out of the lungs. Whew!

If all of this information makes you a little breathless, just remember that the diaphragm is essentially a pump. Like a piston inside a cylinder it moves up and down, sucking air in and squeezing it out of our lungs.

In the ancient Sanskrit language, the word for breath is the same as the word for life, prana. From the Yoga point of view, the air that we breathe contains more than just oxygen, carbon dioxide, and other gases; it contains prana, our life force, that substance from which all life and activity is derived. Prana enters our bodies when we are born and mysteriously leaves us when we die. In the same way that the concept of a person's soul is unlikely to be proven by modern science, so the idea of prana remains unproven. Yet modern science does acknowledge oxygen itself as the most basic of human needs, and the advanced Yoga breathing techniques called prana-yama (prah-nah-YAM-a) teach us to make maximum use of our oxygen for optimum health and vitality. The principle of a life force energy is common in various cultures; in China it is known as Chi, in Japan as Ki.

Just as oxygen is stored and circulated in the blood, Yoga literature suggests that prana is stored and circulated in our bodies. Ancient Yogis practiced Yoga breathing to maintain their prana and thereby increase their health and vitality. Whether or not you accept the concept of prana, Yoga breathing's physiology and benefits are well documented in contemporary science, with advantages ranging from decreased stress to improved mental focus to deeper relaxation.

Think of a sailboat, cutting swiftly through a sun-glinted sea—sails unfurled, bow slightly bobbing—a beautiful sight! Its sleek design conceals the powerful framework and the elaborate systems that all interact for smooth sailing. But without the magic ingredient—wind—these systems are useless. Similarly, without breath, all of the elaborate systems of our bodies would be useless. Just as there are different types of wind to propel a sailboat, some more desirable than others, there are different types of breathing available to us, some more healthy for our bodies than others and each having its own unique effect.

When you're out on that sailboat and the wind comes in short, unpredictable gusts from a variety of directions, you'll have difficulty controlling the craft, and you're going to be tossed around. However, with a calm, steady yet persistent breeze, all systems work in effortless harmony for a pleasant ride. Yoga breathing can bring our bodies into this harmonious state of smooth sailing.

The idea behind Yoga breathing is to make a change in your mental and physical demeanor. It modifies how you normally breathe to a slower, more conscious, focused, and complete breath. It also helps tone and strengthen your abdomen. From the Yoga point of view, the abdomen is your body's center of movement, and if the abdomen is flabby there is a greater tendency toward ill health. Most of the Yoga breathing techniques in this chapter emphasize gently drawing the belly in during exhalation to strengthen and tone those muscles.

There is an old Yoga axiom, The nose was meant for breathing and the mouth was meant for eating. With few exceptions, Yoga breathing is classically taught through the nose, both on inhalation and on exhalation. There is both ageless wisdom and scientific knowledge to support this concept of nasal breathing. First, when you breathe through the nose it slows the breath down because the air is moving through two small openings instead of the one big opening in your mouth. Next, when you breathe through the nose, the air is filtered and warmed (for more on why this is healthy, see Chapter 8). In more advanced breathing techniques of pranayama, the nostrils are opened and closed using the fingertips—referred to as digital pranayama—which affects the length and quality of the breath. Keep in mind that Yoga breathing has its time and place; other forms of exercise, such as swimming and jogging, require different kinds of breathing.

There are temporary conditions, such as seasonal allergies, and permanent conditions, such as a deviated septum, that can make nasal breathing difficult. However, most people with nasal allergies or a deviated septum will be able to do Yoga breathing with no problems. If you have difficulty with nasal breathing, consult a doctor. You may also try to choose positions that keep your body upright and try to determine what part of the day is best for you to do Yoga. If medical care and these suggestions do not work to improve your nasal breathing, try inhaling with your nose, exhaling with your mouth. As a last resort, go ahead and use your mouth for breathing.

When practicing these breathing techniques, it's normal to feel a little lightheaded. Since you are breathing abnormally you could, at first, feel dizzy or a little spacey Not to worry—it's normal. If this happens to you, just rest for a few minutes. These symptoms will be replaced by a greater sense of well-being.

To achieve the optimum benefits from Yoga, your movement should always be contained within a cycle of breath. You begin your breath, then begin your movement. Complete the movement, then complete the breath. A simple bar graph illustrates the relationship of breath and movement:

Another way to consider the relationship between breath and movement is to think about your breath as a wave in the ocean, and the movement as the surfer. The surfer waits for the wave to begin, rides it, then finishes the ride before the wave ends. While practicing Yoga, you first start the wave of your breath, then begin and end your movement, then let the wave subside.

Yoga Breathing Techniques

The following techniques can be used for any of the recommended Yoga routines in this book or as separate exercises while lying or sitting.

If you are using any of the breathing techniques as part of a Yoga routine from Part III, follow those instructions for the number of repetitions. If you are using a breathing technique as a separate exercise, repeat a minimum of twenty to thirty times.

First we'll explore four simple Yoga breathing techniques: Focused Breathing, Belly Breathing, Belly-to-Chest Breathing, and Chest-to-Belly Breathing.

Focused Breathing

The easiest way for beginners to get started with Yoga breathing is to use Focused Breathing. It will help you practice the basic elements common in the more advanced techniques. Think of focused breathing as training wheels for complete Yoga breathing.

Part One

Sit comfortably in a chair and place your hands on your thighs. Your palms can face up or down.

Bring your back up nice and tall and close your eyes.

Observe your state of mind and natural resting breath for a few cycles. Then consciously begin to make your inhalation and exhalation longer, smoother, and deeper than normal. Take control of your breath, rather than letting it happen on its own. Breathe through your nose.

Let there be a natural pause at the top of the inhalation as well as after the exhalation. Notice the effect the pause has on your state of mind. The pause is to help lengthen the breath and to remind you to slow down and concentrate on the process of breath. This pause is an introduction to meditation, the first step toward quieting the mind.

Notice how your breath moves your body especially your rib cage and shoulders. When you inhale the body expands; when you exhale the body contracts.

Focus mentally on just your Yoga breathing. When your mind drifts away bring it back to the breath. Listen to the sound your breath makes. Feel the air entering your nose and expanding your lungs. This is how the breath is used to connect the body and the mind. Eventually the breath and movement become a form of meditation. When you practice focusing, you'll soon notice improved concentration and the quieting of your mind, which is one of the ultimate goals of Yoga. As your concentration improves in Yoga, it also improves in other aspects of your life.

After 25 rounds of Focused Breathing, gradually let your breath come back to normal and sit for a few minutes with your eyes closed. Think about your state of mind when you first started and then compare it to how you now feel. You'll be amazed at how you can shift your overall energy with just your breath.

Part Two

When you're familiar with Part One, begin to gently draw the belly in as you exhale. Make sure you don't strain yourself or pull the belly in too much. Sometimes it helps to visualize wearing a belt with a large buckle in front. During the exhalation phase gently pull the belly in away from the buckle.

Belly Breathing is often used in Yoga for relaxation and pain relief. It differs from Part Two of Focused Breathing in that it requires focus on the belly in both the inhalation and the exhalation phases.

Imagine that you are wearing a wide elastic band around your waist. When you inhale, expand the belly and the band in all directions—front, sides, and back.

During exhalation contract the abdomen. Pause after both the inhalation and the exhalation, and try to keep the chest as still as possible.

Repeat 20 to 30 times if you're doing the breathing exercise without movement or as directed in your Yoga therapy routine.

Belly-to-Chest Breathing

Belly-to-Chest Breathing is often referred to as classic or three-part breathing. It was popularized by Indian Yoga teachers who came to America in the 1960s. This technique incorporates a wave-like motion involving the belly, ribs, and chest and is great for giving your body a little oxygen lift. You can use this breathing where indicated in the Yoga therapy routines or when you feel your brain needs a jump-start to help you focus.

As you inhale, expand your belly, then your ribs, and finally your chest. Pause.

As you exhale, release your chest and ribs, then contract your belly. Pause.

Repeat 20 to 30 times if you're doing the breathing exercise without movement or as directed in your Yoga therapy routine.

The ancient technique of Chest-to-Belly Breathing has been popularized in America since the 1970s by the work of T. K. V. Desikachar. Desikachar demonstrated that Chest-to-Belly Breathing is the most effective method for toning muscles along the spine, counteracting the effects of all our sitting and bending forward. It is also very energizing and can be used when you first wake up in the morning or during that afternoon energy lull.

As you inhale, expand the chest from the top down, continuing this movement downward into the belly, then pause.

As you exhale, slowly draw the belly in, focusing slightly below the navel. Your rib cage will naturally lower. Pause.

Repeat 20 to 30 times if you're doing the breathing exercise without movement or as directed in your Yoga therapy routine.

The use of sound is a special form of Yoga called Mantra Yoga. You produce sound when air leaving your lungs passes over your vocal cords causing them to vibrate. In Yoga tradition, this vibration creates a healing environment for the body and the mind.

The simple sounds that are user friendly in all languages and dialects are ah, ma,and sa. They are easy to use and calming to the body and mind. When spoken during an exhale, these sounds substantially lengthen the breath by narrowing the air passages and slowing the release of air from the lungs.

Sound can also help you coordinate your breath and movement. Some people find the Yoga requirement of focusing on the breath to be somewhat abstract. By adding the ability to focus on a sound, they sometimes find the key to success. Tom, a fifty-six-year-old school psychologist, was referred to me by his physician because of numerous stress-related symptoms. He suffered from anxiety, tension headaches, and insomnia. He was an intellectual and an introvert. As he described it, he was “not in his body.” He had a difficult time understanding how to link his breath and movement, admitting he was uncoordinated. Feeling that he needed something more concrete to focus on, I suggested that he begin to use sound while doing the Yoga postures. He started with the sound of ah for all of the folding movements such as forward bends, side bends, and twists. It was quite a breakthrough. His brain had finally made the connection between his breathing and his action. Soon he was comfortable using any of the three sounds—ah, ma,and sa— with his Yoga practice. With sound, he could easily coordinate his breath and movement. For the first time in his life, Tom had a physical program that he could do on his own and look forward to. The big payoff was that after three months of regular Yoga practice, all of his stress-related symptoms were gone.

To try using sound, practice any of the four simple breathing techniques outlined earlier, and once you become comfortable, add one of the sounds to your exhale. This means you will be opening your mouth, so you'll be exhaling through your mouth instead of your nose. See if this helps you keep your breath slow and measured and your concentration more intense.

Now we'll look at five advanced breathing techniques (pranayama in Sanskrit), popularly known as Victorious Breath, Alternate Nostril Breathing, Shining Skull Breath, Cooling Breath, and Crow's Beak. It is important to practice them only after you have become comfortable with the basic Yoga breathing techniques described earlier.

Victorious Breath

Learning the Victorious Breath is traditionally one of the goals of authentic Yogic breathing. It involves producing a sound like an ocean tide or a baby's breath. It is considered a more advanced skill and can be added to any of the Yoga breathing techniques when you are ready.

Start seated comfortably or standing with the spine erect.

Open your mouth and slowly inhale; as you exhale make a sound at the back of your throat like the ocean's incoming tide or a whispering haaa.

Now add the sound to your inhale as well. Repeat a few times.

Then close your mouth, breathe through the nose on both the inhale and exhale, and make the same sound focusing on the back of your throat and the chest.

Make the breath long and smooth with the normal pauses at the top of the inhale and the bottom of the exhale. It is easier to learn Victorious Breath on the exhale phase. Use this type of breathing to slow yourself down even further and to deepen your concentration.

Alternate Nostril Breathing (ANB) was developed because Yoga masters knew what researchers have only recently proven in the lab: We don't breath evenly through both nostrils. In a cycle that lasts a few hours, each nostril becomes alternately dominant. ANB helps create balance and harmony in your system by allowing each nostril equal time so that while you are practicing, neither nostril is dominant. This can also help strengthen the breath of a nostril that may be chronically weaker. There are several forms of Alternate Nostril Breathing. The following exercise, called Channel Cleansing, is a safe and popular form of ANB that can easily be practiced by beginners.

Sit comfortably in a chair, or on the floor in a simple crossed-legged position. Bring your back up nice and tall.

Hold up your right fist with the palm toward you and then extend the right thumb and last two fingers. Your index and middle fingers are folded down.

Place your right thumb on the side of your right nostril, and the ring and little fingers on the side of your left nostril.

Block off the right nostril and inhale freely into the left. Then block off the left nostril and exhale out of the right. Then reverse it: Inhale into the right nostril while blocking the left, and exhale out of the left while blocking the right.

Repeat the cycle 10 to 12 times.

In your first session practicing this technique, start with inhalations and exhalations of five to seven seconds each. Over time as you continue to practice, gradually increase the length of your breath until you reach your comfortable maximum. You can also gradually increase the length of your sessions until you reach five to ten minutes. If a Yoga routine in this book instructs you to do Alternate Nostril Breathing and you have difficulty doing it, you may substitute Belly-to-Chest Breathing or Victorious Breath.

The Shining Skull Breath exercise has an energizing effect and is great for the physical or mental blahs. In the beginning, this exercise may leave you feeling lightheaded, but it's a great pick-me-up when you need to be alert. During my corporate days, we all had to attend laborious meetings. If I had a hard time staying awake, I would excuse myself for a restroom break, do two or three sets of Shining Skull Breath and come back to the meeting wide awake. The Shining Skull Breath is not recommended just before bedtime, as it may be too stimulating; and it should not be used during pregnancy. The focus is on short rapid inhalations and exhalations using your nose.

Sit comfortably in a chair or on the floor in a simple cross-legged position. Bring your back up nice and tall and place your hands on your thighs or in your lap.

Take a deep inhale through your nose, then exhale quickly through your nose, strongly contracting your abdominal muscles. Rest your hands on your lower belly to feel the contraction. Let the contraction push the air out of your lungs.

Then just as quickly, release the contraction, and watch how the breath is automatically drawn back into your lungs.

Repeat this quick contraction–release cycle 15 to 20 times in succession. Each exhalation is about one second.

Go slowly at first; and then after you have practiced for a few days, pick up the pace and add ten to fifteen more cycles. You could also do two sets of cycles, with a ten- to fifteen-second rest between the sets.

A great technique for mellowing out during stressful times is the Cooling Breath. It's also effective for quieting hunger or thirst when necessary.

Sit in a comfortable position on the floor. Bring your back up nice and tall. Place your hands on your thighs or comfortably on your lap.

Curl your tongue vertically and let its tip protrude slightly from your mouth. (The ability to curl your tongue vertically, so that from the front it looks like a U, is genetic. If you can't curl your tongue, try Crow's Beak, described next.)

As you inhale, slightly tilt your head back while you slowly suck the air in through the funnel formed by your tongue. Then tilt your chin back down as you exhale slowly through your nose.

Repeat 10 to 20 times. Gradually increase to 5 to 10 minutes.

Crow's Beak

The Crow's Beak is an alternative if you are unable to curl your tongue for Cooling Breath. This technique has the same benefits as Cooling Breath.

Sit in a comfortable position on the floor. Bring your back up nice and tall. Place your hands on your thighs or comfortably in your lap.

Pucker your lips as though you were going to suck in air through a straw. As you inhale, slightly tilt your head back while you slowly suck the air in through your puckered lips. Then tilt your chin back down as you exhale slowly through your nose.

Repeat 10 to 20 times. Gradually increase to 5 to 10 minutes.