unsicht-bar was suggested to us in connection with a sensory conference we were attending in Hamburg. We made reservations several weeks in advance. Normally, the restaurant is closed on Mondays, but with thirteen excited Danes as prospective diners, Unsicht-Bar flung wide its doors to us. A nice gesture: our expectations were rising. At the conference, rumors spread that we were going out for a special meal. Thus, we ended up being a party of thirty-four sensory scientists. Sensory scientists will generally go far out of their way for anything having to do with extraordinary food. As for the literally dark culinary event we were about to experience, we only knew it was going to open our eyes to new ways of looking at food.

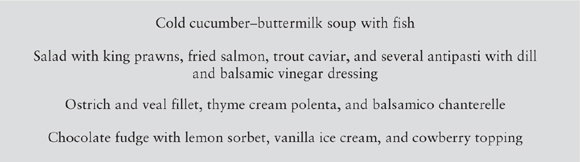

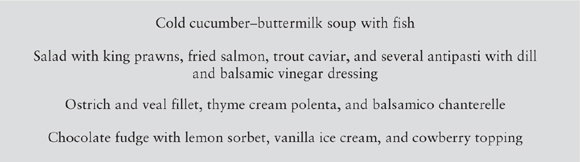

Upon our arrival in the foyer, we were grouped into small parties, and orders for food and drinks were taken. It was explained to us that we could choose from among four menus: beef, poultry, vegetarian, or the surprise menu. Needless to say, the majority selected the surprise menu—why else would we come here? The items on the surprise menu (figure 54) would be disclosed after diners had finished the meal.

Each group of diners entered the dining room together with their waiter and were seated. It was a big room but with good acoustics. The conversation at other tables was audible but not intrusive. Our table did not have a table cloth. There were place mats for each of us. The Ikea-savvy among us recognized them instantly. The table arrangement was flexible; there was Velcro at the table edges aiding the stability of our two juxtaposed tables, which created a four top. The waiter arrived with our drinks—wine by the glass. He announced that an amuse-bouche (complimentary appetizer) would shortly follow. We started rolling out the thick paper napkins. One of the diners decided to put his napkin in the neck opening of his shirt. That night he wanted to be particularly sure it did not fall to the floor. The amuse-bouche—prawns on a slice of baguette—arrived on one plate and was placed in the center of the table. Prawns are such a familiar and easy-to-recognize flavor. These had a wonderful soft and juicy texture. When a baguette is good, the crust is so crisp—almost glasslike—that it shatters on the bite. It was an especially good baguette: the textural difference between the crust and the soft crumb was particularly pronounced. Shortly after, our soups arrived. The smoked salmon revealed itself from a distance; therefore, it was easily decoded. The soup bowl had “ears,” making it easier to drink the soup. No one at our table was able to recognize the buttermilk in the soup, so it was a surprise when we saw it on the menu afterward.

Figure 54 The surprise menu.

The second course was a salad, and almost every bite was a surprise. As we were eating from the surprise menu, we were not especially amazed. When the salad course was served, an aroma of clear marine origin enveloped us. We reached a consensus on fish eggs of some kind, but it took many bites before we experienced their texture and taste. Smoked salmon, now part of the salad, again gave itself away from a distance by its smell alone. Fennel was easy to recognize by its aniselike aroma. Normally, the texture of its surface is nothing spectacular. But for us, totally unaware of its presence, it felt remarkably slippery yet not smooth—we could feel the small rims on the surface. The prawns were gigantic, and it was difficult to eat one in a single bite. Remarkably, the dill went unnoticed by several diners, possibly because there was so little of it. Several of us did not notice that there were two different animal species as part of the main course—veal and ostrich. The dessert was literally plate-licking delicious!

At one point, one of the diners had to use the restroom. He called for the waiter. The waiter laid the diner’s hands on his shoulders, escorting the diner to the light lock—the light was intensely strong after the total darkness of the restaurant. But it did not matter. The diner had his sight again, and probably anyone going to the restroom was thankful for that! To the waiter, light or dark did not make a difference—he was blind, like the rest of the dining room staff.

It was an extraordinary experience to eat a whole meal in the dark at Unsicht-Bar {Unsichtbar is the German word for “invisible”). When we are deprived of one of our key senses, our impression of the world can change radically. In connection with eating, visual input generates expectations about what is to come. In the absence of these expectations, our other sensory impressions of food are dramatically altered. From the first second of darkness, this resulted in a very different impression of the room as the remaining senses sharpened to get a grasp of the surroundings. When first seated, we touched everything, feeling the square table, the round plate, the glasses, and the place mat. The lack of visual stimulation highlighted some sensory properties, like the texture of the baguette and the slipperiness of the outer surface of the fennel. Because appearance is a major factor in the identification of foods with less familiar aromas, tastes, and textures, darkness hinders our ability to decode what we are eating. The setting invited deep discussions about what we perceived and also encouraged behaviors that are otherwise inappropriate in other restaurants—licking your plate, for instance!

Some of us dealt better with the discomfort of visual deprivation than others. Two diners at our table felt quite uneasy at the beginning. Would we be able to leave the room if something went wrong? Things started to feel better when we were served the drinks and the starter. Drinks were given to us using sounds as a directional guide (the waiter clicked his wedding ring on the side of the glass). The experience of the Unsicht-Bar meal was markedly different from that of a meal in a regular restaurant setting. We did not have our sight to help us generate expectations for what we were about to eat. When the aromas from the dish failed to give it away, we had to actually touch the dish before we had any idea what it was. As it happens, our experience eating blind at the Unsicht-Bar was not at all what we expected it would be. We had thought that it would be like being blindfolded in an illuminated room, as in familiar childhood tasting games. The experience is much more powerful than that. Even with our eyes wide open, we still did not see a thing. Obviously, it is difficult to generate expectations about something for which there is no point of reference.

Overall, we found that the conversation was different from the usual chatter. Inevitably, the talk turned to the scene in the movie 9½ Weeks in which Mickey Rourke blindfolds Kim Basinger and feeds her all sorts of delicacies. It is a classic scene showing the proximity of food and lovemaking. Other topics we took up were much more serious. It was our feeling that the darkness and the sharing of such an extraordinary experience made the conversation more sincere. And we strongly agreed we had been through something utterly wild, creating a sense of togetherness among us.

This account of our experience at Unsicht-Bar shows that an unusual setting will affect the perception of a meal. It vividly demonstrates that visual input is vital for the generation of sensory expectations, and in the absence of these expectations, many of the sensory impressions change. It highlights that a range of processes we take for granted and effortlessly do in connection with eating are really quite complex.

The fact that the eating experience is such a complex, multidisci-plinary, and vital phenomenon has resulted in its examination through many different fields of study, including sociology, economics, nutrition, and the arts. Food has always been of great economic concern, and with the growing interest in and attention paid to food culture, health concerns, and the “experience economy,” it has become a part of the political agenda. In this buyer’s market, food shopping for an increasing segment of the population has changed from a search for inexpensive macronutrients to a search for experiences. A food product provides energy to the body but also conveys meaning through cultural codes. It is an expression of the identity we wish to possess.

The experience of a meal is affected by a variety of factors in addition to the food itself. It is a highly personal process influenced by our physiological and psychological history, attitudes, mood, and other variables. In a restaurant, along with these personal factors, contextual effects, such as the setting, the staff, the service, and the company certainly all contribute to the way the meal is perceived.

Every meal has a host and is dictated by ritual. The host, visible or not, has a major influence on the eating experience of the individual. This influence exhibits itself in a sense of confidence on the part of the host and trust on the part of the guest. Also, the host creates the frame in which the eating takes place. This frame is an important part of the food experience. In some cases, as in fine dining, there is seemingly no limit to the cost and the imagination. The host-guest relationship is of great importance to the dining experience. Good examples of unusual eating places in this respect are the Unsicht-Bar in Berlin and Madeleines Madteater in Copenhagen. At Madeleines, theater, restaurant, and food laboratory are fused together to give an exquisite overall narrative and sensory experience. The waiter’s job at both establishments is not just to guide and navigate the guests but also to make them feel comfortable and secure in an unfamiliar situation. According to Jan Krag Jacobsen (2008), the exquisite eating experience is a question of cultural capital. It is a dialectic produced by skilled chefs—but also skilled consumers—qualified to enjoy the experience.

When does the experience of fine dining begin? The experience of a restaurant meal starts long before we sit down to eat. When we read about restaurants, hear other people talk about a specific place, and decide to book a table at a specific establishment, we are already generating expectations about how it will be to dine there. This expectation process continues until we are actually dining. Our expectations influence our experience of the meal. Often, especially in fine dining, our expectations are extremely high, and thus they are at risk of being disconfirmed. The effect of disconfirmed expectations on sensory perception can be accounted for by four different psychological theories: assimilation, contrast, assimilation-contrast, and generalized negativity. Assimilation theory states that an unconfirmed expectation creates a kind of psychological discomfort because it contradicts the consumer’s original expectation. Consumers, therefore, try to reduce this discomfort by changing their perceptions to more closely align with their expectations. Thus the perceived “product performance”—the meal in a restaurant—assimilates to the expected performance. According to contrast theory, disconfirmed expectations will result in an exaggeration of the disparity between expected and actual stimulus properties. For instance, according to this theory, a restaurant’s modestly understated advertising will result in higher consumer satisfaction. Conversely, a restaurant that has been presented as better than it actually is will result in a considerable decrease in consumer satisfaction. Contrast theory is, therefore, the reverse of assimilation. Assimilation-contrast theory dictates that there are boundaries inside which our perception assimilates to our expectations, but outside those boundaries, differences between actual perception and expectations will be exaggerated. Finally, generalized negativity predicts that when an experience is not as expected, it is perceived as negative. Most studies in consumer food science support assimilation or assimilation-contrast theory. These theories have never been studied with respect to disconfirmed expectations in restaurant meals, but it is plausible that assimilation-contrast occurs. In the particular case of fine dining, it may well be that the difference between expectations and actual experience need be only very subtle before we see the contrast effect.

Most sensory consumer studies tend to concentrate on the food itself, with many factors having been found to influence the consumer’s responses to the food products. In restaurant settings, other factors affect the perceived quality of the food served. It is possible that the food alone may have less influence on perceived quality than the environmental factors that come into play.

An emerging field within both hospitality science and consumer food science is the study of eating in real-life situations. Research has been done to investigate the effect of a variety of contextual factors on the perception of foods and dishes. In a study conducted in a student cafeteria, Brian Wansink, Koert van Ittersum, and James E. Painter (2005) found that more evocative and descriptive menu names, such as Satin Chocolate Pudding, generated greater positive feedback and higher ratings—the dishes attached to these names were deemed more rich, tasty, and generally appealing than the otherwise straightforwardly named menu items, such as Chocolate Pudding.

Dishes at highly experimental restaurants are different from those at standard restaurants because many of them—besides being delicious—are meant to challenge and surprise the diner. We have examined how different menu-item descriptions affect the diner’s perceptions in a restaurant setting. Among other answers, the intention was to discover whether the positive effect of hedonically evocative descriptions of menu items extends to fine dining. In our study, diners were served an eleven-course tasting menu and answered a short questionnaire after each course. Dishes were developed by Torsten Vildgaard, creative sous-chef at Noma in Copenhagen. We used four different descriptions for a single dish: the title only; the title and sensory information; the title and information about the culinary processes; and the title plus hedonically evocative information. Results showed that the kind of information affected the perception of the dish, but there was also an interaction effect with the dish. This indicated that there is a complex interplay between a dish, its presentation, and our perception of it. One dish we served was Brie parfait rolled in rye bread crumble and a rhubarb sherbet. The hedonically evocative presentation was presented as follows:

Cheese and rhubarb: a delicious and creamy parfait is united with a refreshingly cooling rhubarb sherbet, which assembles in the mouth as pure enjoyment

By contrast, the information about the culinary process was presented in this way:

Cheese and rhubarb: this dish was frozen at a very low temperature (-22°F [-30°C]) and the ice crystals were comminuted using a Pacojet.

Interestingly, people who ate the dish based on the hedonically evocative description liked it the least. Our interpretation is that for these novel dishes, the information about the culinary process better links the raw materials to the served dish, and thus makes it easier for the diners to understand what they are about to eat.

With restaurant studies, there are many considerations to take into account. In consumer studies in particular, the experiment is often performed in an artificial eating environment, often a light-, temperature, and humidity-controlled confined sensory booth. The evaluations of food products under those conditions are stripped of the normal eating context. Therefore, the results are not necessarily reliable predictors of consumer choice in the real world. To achieve valid and reliable data, studies should always be performed in environments as close to the real examples as possible. Scientists seek experimental objectivity and reproducibility of data. This is often accomplished by keeping all factors—other than the experimentally varied—constant and by keeping track of every single detail. Laypersons might label researchers control freaks. However, maintaining complete control in a restaurant setting is impossible. There is simply no such thing as a controlled restaurant environment that simultaneously reflects the true eating situation. We have to live with the challenges of real-life situations, such as diners that make conversation at the table during an experiment.

The mere act of having diners consciously consider their perceptions and give their opinion affects the restaurant experience. This certainly poses research challenges in the field. An alternative approach is the observational study, in which, rather than offer their opinion, diners are merely observed, either by experimenters or video cameras. In the Netherlands, at the Restaurant of the Future, up to two hundred patrons can be monitored by hidden cameras. For more ordinary meals away from home, observational study is definitely a feasible strategy for examining eating behavior. In fine dining, the situation is somewhat different. The motivations behind a guest’s choice of dining experience may go well beyond merely eating food to satisfy hunger or choosing dishes that sound mouthwatering. The eating experience in high-end restaurants is as much a narrative for the chef as it is a sensuous voyage of discovery for the diners. Properties of the food, such as perceived novelty, familiarity, and complexity, are central in our appreciation of it. The emotions that the food elicits, such as curiosity or surprise, are necessary for the pleasure obtained from fine dining. Our research is, in part, complete. In future studies in restaurant settings, we hope to gain new insights into the dining experience that we can share and that will further enhance all diners’ enjoyment of food.

This work is supported financially by the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation through the Danish Research Council for Independent Research Technology and Production Sciences.

Gustafsson, I. B. 2004. “Culinary Arts and Meal Science: A New Scientific Research Discipline.” Food Service Technology 4, no. 1:9–20.

Jacobsen, Jan Krag. 2008. “The Food and Eating Experience.” In Creating Experiences in the Experience Economy, edited by Jon Sundbo and Per Darmer, 13–32. Cheltenham, Eng.: Elgar.

Köster, E. P. 2003. “The Psychology of Food Choice: Some Often Encountered Fallacies.” Food Quality and Preference 14, nos. 5–6:359–373.

Mielby, L. M., and M. B. Frost. 2010. “Expectation and Surprise in a Molecular Gastronomic Meal.” Food Quality and Preference 21, no. 2:213–224.

Wansink, B., K. van Ittersum, and J. E. Painter. 2005. “How Descriptive Food Names Bias Sensory Perceptions in Restaurants.” Food Quality and Preference 16, no. 5:393–400.

Wurgaft, B. 2008. “Economy, Gastronomy, and the Guilt of the Fancy Meal.” Gastronomica 8, no. 2:55–59.