- DIFFICULTY: high

- TIME LENGTH: long

- DECKS: 1

If you are new to Bridge, you have a long road ahead of you. This is not intended to frighten you off. Instead, it’s meant to manage your expectations. There are thousands—literally—of books dedicated to Bridge, and committed players can spend lifetimes mastering its nuances. That’s because Bridge is complicated. And worst of all, you need at least four people to play a proper game of Bridge—not two, three, or five, but precisely four, preferably with similar amounts of playing experience.

Now for the good news. Even detractors acknowledge that Bridge is among the world’s finest card games. If you commit time and mental energy to learning Bridge, after just a few hours you will be hooked. It’s OK if you don’t immediately understand every twist and turn. With even a rudimentary understanding of Bridge’s rules and strategies, you will enjoy it.

A BRIEF HISTORY All Bridge games are descendants of Whist. In 1905, Whist enthusiasts in London, New York, and Boston codified a new form of the game, called Auction Bridge. In 1926, the millionaire Harold Vanderbilt tinkered with the game’s rules on a Caribbean cruise and singlehandedly invented Contract Bridge. Enter Ely Culbertson and his wife (an Auction Bridge teacher), Josephine Dillon. They took Contract Bridge and turned it into an international phenomenon in the 1930s and ’40s, making and losing many millions of dollars along the way.

A BRIEF HISTORY All Bridge games are descendants of Whist. In 1905, Whist enthusiasts in London, New York, and Boston codified a new form of the game, called Auction Bridge. In 1926, the millionaire Harold Vanderbilt tinkered with the game’s rules on a Caribbean cruise and singlehandedly invented Contract Bridge. Enter Ely Culbertson and his wife (an Auction Bridge teacher), Josephine Dillon. They took Contract Bridge and turned it into an international phenomenon in the 1930s and ’40s, making and losing many millions of dollars along the way.

Ely Culbertson, credited as the man who made Bridge, wrote no less than ten Bridge books, and transformed the game into a mainstream success. Culbertson was also a true character. In his autobiography, The Strange Lives of One Man, he writes, “This is the complete story of my life, told as candidly and as ruthlessly as I could. All the names and places, including the jails, mentioned herein are authentic.”

Contract Bridge (sometimes called Rubber Bridge) is the quintessential version of the game, and it’s the game described first below. Contract Bridge is a bidding and trick-taking game. At the start of each hand, the teams bid on how many tricks they think they can win. The team with the highest bid earns (or loses) points based on whether they achieve their bid. Over the years, other popular variations have evolved, including Duplicate Bridge (played at professional tournaments), Chicago Bridge (a simplified four-deal version), and Honeymoon Bridge (for two players).

NUMBER OF PLAYERS Bridge is always played by four players divided into two teams. Partners sit facing one another, and are universally referred to as North, South, East, and West, based on their positions around the table. The teams, then, are North-South and East-West.

NUMBER OF PLAYERS Bridge is always played by four players divided into two teams. Partners sit facing one another, and are universally referred to as North, South, East, and West, based on their positions around the table. The teams, then, are North-South and East-West.

HOW TO DEAL A standard fifty-two-card deck is used. Card rankings are standard, with aces always high. The suits rank (high to low) no trump, spades, hearts, diamonds, clubs. No trump (abbreviated NT) means there is no trump suit, and it acts like a fifth suit for the purposes of bidding. Spades and hearts are major suits and score higher contract values than diamonds and clubs, which are minor suits.

HOW TO DEAL A standard fifty-two-card deck is used. Card rankings are standard, with aces always high. The suits rank (high to low) no trump, spades, hearts, diamonds, clubs. No trump (abbreviated NT) means there is no trump suit, and it acts like a fifth suit for the purposes of bidding. Spades and hearts are major suits and score higher contract values than diamonds and clubs, which are minor suits.

All dealing is clockwise. Deal thirteen cards to each player, one at a time. It’s important to have a second deck of cards at the ready, shuffled by the dealer’s partner. At the end of one hand, the alternate deck is used to deal the next, to speed the game along.

BIDDING Most of Bridge’s complexity is in the bidding. At its simplest, bidding determines the minimum number of tricks a team must win, as well as the trump (or no trump) suit for the hand.

BIDDING Most of Bridge’s complexity is in the bidding. At its simplest, bidding determines the minimum number of tricks a team must win, as well as the trump (or no trump) suit for the hand.

Bids always assume a base of six, so that a bid of 1 commits you to winning seven tricks, a bid of 2 commits you to winning eight tricks, etc. Since suits are ranked in Bridge, a bid of 2 of hearts beats a bid of 2 of diamonds or 2 of clubs, but loses to a bid of 2 NT, 2 of spades, or to any bid of three or higher.

The dealer always opens the bidding, which then proceeds clockwise around the table. The dealer may pass or make a bid at any level. The bid is intended to communicate information about the dealer’s hand to his or her partner (more on bidding strategies later). Either way, the next player either must pass or beat the dealer’s bid. For example, if the dealer opens with 2 of diamonds, the next player must bid 2 of hearts or more, or pass.

Players may also double an opposing team’s bid, which effectively doubles the point value of the previous player’s bid and is used to punish a team for overbidding. For example, if North opens with 2 of diamonds and East replies with an aggressive bid of 4 of spades, South may double. This means South believes East has overreached and is likely to lose the bid of 4 of spades.

A team that’s been doubled may then redouble the bid. This is akin to a doubledare, and it quadruples the points at stake. In the example above, West might redouble South’s double of East’s 4 of spades. Note that if the next player in rotation makes a higher bid, all doubles and redoubles are canceled. So in the example above, if North replies to West’s redouble with a bid of 4NT, the doubles and redoubles are ignored and East must decide whether to overcall (e.g., make a higher bid, in this case any bid of five or more) or to pass.

A typical bid can be diagrammed as follows, starting at North and with East-West ultimately winning the contract at 4 of hearts:

| NORTH/EAST |

SOUTH WEST |

| Pass/1 of hearts |

1 of spades/2 of diamonds |

| 2 of spades/Double |

Pass/4 of hearts |

| Pass/Pass |

Pass/-- |

Players who pass are allowed to rejoin the bidding on their subsequent turns. The bidding ends when three players in a row pass. The winning bid is called the contract, and the player who opens the bid in the winning suit is the declarer. In the example above, even though West makes the highest hearts bid, East is the declarer because East opened bidding in hearts.

BIDDING STRATEGY Players always start by calculating their hand’s point value. This is a simple two-step process:

BIDDING STRATEGY Players always start by calculating their hand’s point value. This is a simple two-step process:

First, calculate your high-card points: 4 points for an ace, 3 for a king, 2 for a queen, 1 for a jack. There are 40 total high-card points in a deck, so you’re in a decent position if you hold more than 10 points.

Next, calculate your long-suit points. Score yourself 1 point for each card in a suit longer than four cards. For example, if you hold six diamonds, score yourself 2 long-suit points.

So, the hand A of spades-K of spades-10 of spades-5 of spades-Q of hearts-J of clubs-10 of clubs-8 of clubs-5 of clubs-3 of clubs-2 of clubs-K of diamonds-5 of diamonds contains 13 high-card points plus 2 long-card points, for a total of 15 points. The rule of thumb for bidding in Bridge is:

Pass with fewer than 12 points.

With 13 or 14 points, bid at the one level in your longest suit.

With 15 or more points and a balanced hand (e.g., you have at least two cards in every suit) bid 1NT.

Once the bidding starts, short-suit points are added to your score if and when your partnership finds a suit fit. This helps you decide whether to bid or not for a slam or a game. The rule of thumb for determining suit fit: You must hold four or more cards in the suit bid by your partner (e.g., your partner opens 1 of spades and you have four-card support in spades). In this case, give yourself the following short-suit points:

5 points for a void (no cards) in any suit.

3 points for a singleton (just one card in a suit). Don’t score yourself high-card points and singleton points. A singleton K of diamonds, for example, scores 3 points for high card or 3 points for the singleton, but not both!

1 point for a doubleton (just two cards in any suit).

Whenever possible, teams try to make the following contracts to earn bonus points at the end of the hand:

SMALL SLAM This is a bid of 6 of spades, 6 of hearts, 6 of diamonds, 6 of clubs, or 6NT. You may lose only one trick to your opponents. Teams should hold at least 33 to 36 points to bid a small slam.

GRAND SLAM This is a bid of 7 of spades, 7 of hearts, 7 of diamonds, 7 of clubs, or 7NT, and requires a team to win every single trick! To bid a grand slam, teams should hold at least 37 points between them.

It’s OK if you cannot secure a slam contract. It just means you’re not eligible for bonus points (or liable for penalty points) at the end of the hand.

One final note: There are numerous systems for bidding in Bridge, known as bidding conventions. If you’re interested in learning a specific bidding method, such as the popular Blackwood Convention, visit a Web site like the American Contract Bridge League (www.acbl.org).

HOW TO PLAY The player to the left of the declarer leads the first trick, and as soon as the first card is played, the declarer’s partner turns over his cards, organized into columns by suit. This player is known as the dummy, not because they’re a dull knife or a dim bulb, but because the dummy plays no role in the hand from this point forward.

HOW TO PLAY The player to the left of the declarer leads the first trick, and as soon as the first card is played, the declarer’s partner turns over his cards, organized into columns by suit. This player is known as the dummy, not because they’re a dull knife or a dim bulb, but because the dummy plays no role in the hand from this point forward.

Instead, when it’s the dummy’s turn in rotation to play a card, the declarer chooses which card to play. The dummy sits back, refills players’ drinks, and otherwise stays out of the way. The dummy is not allowed to discuss strategy or offer any advice to any player.

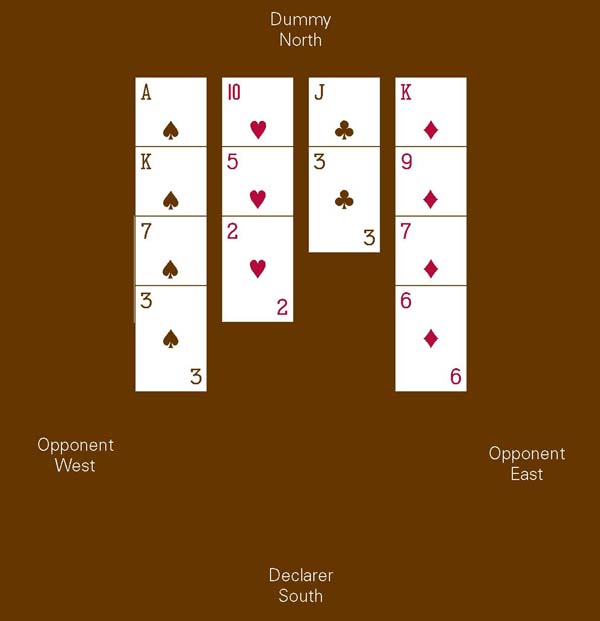

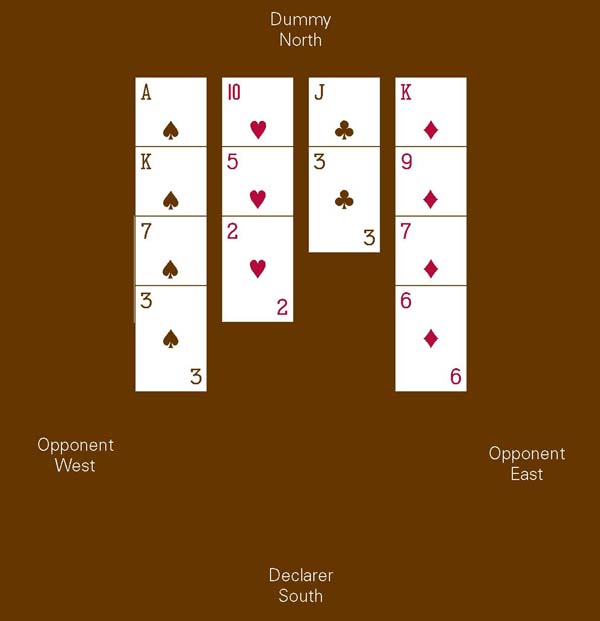

A typical Bridge hand, therefore, can be diagrammed as follows, with the North-South team having won the bid against the West-East team. In this example, South is declarer and North is dummy:

If West opens with 8 of diamonds, for example, the declarer plays a card from the dummy’s hand and the turn shifts to East. All players must follow suit if possible; otherwise they may play any card in any other suit, including trump. Tricks are won by the highest trump played or, if none, by the highest card in the leading suit. The winner of each trick leads the next trick.

Table position is important in Bridge. In the example above, assume that hearts are trump and that South knows (based on how East-West interacted during the bidding phase) that East holds a strong hand of diamonds. In this case, South will try to finesse a trick by leading, say, 9 of diamonds from the dummy (South does this by having the dummy win a trick, in order to lead the next).

If East holds A of diamonds, J of diamonds, 10 of diamonds, 5 of diamonds, they’re in a pickle. Against a lead of 9 of diamonds, East could play A of diamonds to guarantee winning the trick. But this is a risky move: against A of diamonds, South will inevitably play a low diamond, resulting in East overplaying (a nice way of saying “wasting”) the ace. Yet if East plays J of diamonds instead, South might play Q of diamonds and win the trick. And any play that captures a trick with a low card—against an opponent holding a higher card in the same suit—is called a finesse. It’s a thing of beauty when it works, unless of course you’re on the losing end of it.

SCORING In Bridge, teams compete to win rubbers, which consist of three games. Whichever team wins two out of three games wins the rubber. It takes 100 points to win a game. Points are awarded as follows (for each trick in excess of six):

SCORING In Bridge, teams compete to win rubbers, which consist of three games. Whichever team wins two out of three games wins the rubber. It takes 100 points to win a game. Points are awarded as follows (for each trick in excess of six):

20 points per trick for contracts in clubs or diamonds. A successful contract of, say, 3 of diamonds earns 60 points (three tricks × 20 points each).

40 points per trick for contracts in spades or hearts. A successful contract of 2 of hearts earns 80 points (two tricks × 40 points each).

40 points for the first trick and 30 points for all subsequent tricks in no-trump contracts. A successful contract of 2NT earns 70 points (1 × 40 points plus 1 × 30 points).

Keep score on a piece of paper divided into two sections: above the line and below the line. Successful contracts are scored below the line and count toward winning a game. Bonus scores for overtricks (tricks in excess of the contract) and undertricks (tricks shy of the contract) are scored above the line and do not count toward a game.

Double all above-the-line points when the contract is doubled; quadruple the points when the contract is redoubled. And don’t forget to score an extra bonus of 50 above-the-line points to the declarer’s team if they succeed in making a doubled contract.

BONUS POINTS In each rubber, teams that have won a game are considered vulnerable, while teams that have not are not vulnerable. Points for slam contracts are as follows:

If your team is not vulnerable, score an above-the-line bonus of 500 points for a small slam, 1,000 points for a grand slam.

If your team is vulnerable, score an above-the-line bonus of 750 points for a small slam, 1,500 points for a grand slam.

The declarer’s team also scores an above-the-line bonus for each overtrick earned, using the same point values as the contract bids. For example, a successful 2 of hearts contract with 2 overtricks (e.g., your team won ten total tricks in the hand) scores 80 below-the-line points for the 2 of hearts contract plus 80 above-the-line bonus points for capturing those two extra tricks. If the contract was doubled or redoubled, you earn even more bonus points, depending on whether your team is vulnerable or not.

If your team is not vulnerable, score an above-the-line overtrick bonus of 100 points (doubled) or 200 points (redoubled).

If your team is vulnerable, score an above-the-line overtrick bonus of 200 points (doubled) or 400 points (redoubled).

If the declarer’s team fails to make its contract, no below-the-line points are scored. However, the opposing team earns above-the-line bonus points as follows:

If the declarer’s team is not vulnerable, the opposing team scores 50 points per overtrick or, if doubled, 200 points for the first overtrick and 300 points for each subsequent overtrick. If the contract is redoubled, the opposing team scores 400 points for the first overtrick and 600 points for each subsequent overtrick.

If the declarer’s team is vulnerable, the opposing team scores 100 points per overtrick or, if doubled, 200 points for the first overtrick and 300 points for each subsequent overtrick. If the contract is redoubled, the opposing team scores 400 points for the first overtrick and 600 points for each subsequent overtrick.

When a team wins two games, they win the rubber and receive a 500-point “rubber bonus” if their opponents are vulnerable. Otherwise, they earn a rubber bonus of 700 points.

A typical Bridge game might be scored like so:

| NORTH-SOUTH |

EAST-WEST |

| 40 |

- |

| 500 |

- |

| - |

40 |

| 60 |

120 |

In the first hand, North-South wins a 3 of diamonds contract and captures eleven total tricks, for a score of 60 below the line and 40 above the line for overtricks. In the second hand, East-West fails to make a doubled contract of 3 of hearts by two tricks. So North-South scores 500 above-the-line points (on a doubled contract that’s 200 points for the first undertrick, 300 points for the second undertrick).

In the third hand, East-West wins a contract of 3 of hearts and captures ten tricks, for a total of 120 points below the line and 40 points above the line for one overtrick. This earns East-West the game and makes them vulnerable in the next game. The total points at the end of the first game are 600 points for North-South, 160 points for East-West.

VARIATION 1: CHICAGO BRIDGE

The rules of this variation are identical to Contract Bridge. The main difference is that a rubber lasts for four deals—no more, no less. The idea here is to simplify and speed up the normal Contract Bridge game. In Chicago Bridge, vulnerability is “assigned” (since it’s unlikely to develop on its own in just four hands) as follows:

Deal 1: North deals, neither team vulnerable

Deal 2: East deals, North-South vulnerable

Deal 3: South deals, East-West vulnerable

Deal 4: West deals, both sides vulnerable

If both teams pass on the bidding, the hand is dead, and cards are shuffled and redealt by the very same dealer. Game bonus is 500 points (vulnerable) or 300 points (not vulnerable). Partial scores are carried over until a team wins a game, at which point the partial score is erased. In Hand 4 only, score either team a bonus of 100 points if they earn a partial score.

VARIATION 2: DUPLICATE BRIDGE

Most players agree that luck plays a small but crucial role in Contract Bridge. That’s because a mediocre team dealt good cards will usually beat a better team holding mediocre cards. The luck of the draw has an impact. This is not the case in Duplicate Bridge, where hands are replayed by different sets of players to eliminate the luck factor.

Duplicate Bridge is typically played in Bridge clubs, since you need specialized equipment (sixteen “boards” that are numbered sequentially, each containing four pockets labeled N, S, E, W to stash the pre-dealt Duplicate Bridge hands) and large numbers of Bridge players (eight players for two teams of four, or twelve players for a three-table game). If you’re new to Bridge and aspire to club play, learn more about Duplicate Bridge at the American Contract Bridge League (www.acbl.org).

VARIATION 3: HONEYMOON BRIDGE

Bridge is best played by four people. That said, there is a semi-enjoyable two-player version called Honeymoon Bridge. The two players sit next to each other, and one of them deals out four thirteen-card Bridge hands. The hand opposite each player is their own personal dummy hand, which should not be looked at until after the bidding. The bidding alternates between the two players until one player passes. At this point, the two players review their own dummy hands but still keep them concealed until after the first card is played. Lead from the hand that is to the declarer’s left (either dummy or player, whichever is appropriate). Then turn over both dummy hands and follow the normal rules of Contract Bridge. Each player pulls cards from his own dummy when it’s his dummy’s turn.

VARIATION 4: CUTTHROAT BRIDGE

The three-player version of Bridge follows the Contract Bridge rules, with only a few exceptions. Deal four thirteen-card hands (one to each player plus a dummy hand); bidding is opened by the dealer. Once two players in a row pass, the declarer automatically plays with the dummy hand against the two other active players. The player to the declarer’s left leads the first card, after which the dummy hand is turned up. The rest of the game proceeds as normal.

Each player keeps her own separate score. If the declarer makes the contract, she earns the standard points. If the declarer fails to make the contract, the two opponents each score for undertricks. If either opponent has honors, both score it. The rubber bonus is 700 points if neither opponent has won a game, otherwise the bonus is 500.

VARIATION 5: AUCTION BRIDGE

Auction Bridge, popularized in the early 1900s, put the nail in the coffin of Whist and was the very first version of modern Bridge to have mainstream success. There are no differences at all in the way Auction Bridge and Contract Bridge are played—the only difference is in scoring. In Contract, overtricks do not count as below-the-line points towards game; in Auction Bridge, all the declarer’s tricks are scored below the line and count towards game score, which means the declaring team can afford to be less accurate in their bidding.

In Auction Bridge, each odd trick (the number of tricks more than six won by the declarer) scores towards game, even if the tricks were not contracted. The trick values are as follows:

|

NORMAL/DOUBLED/REDOUBLED |

| No Trump Contract |

10/20/40 |

| Spades Contract |

9/18/36 |

| Hearts Contract |

8/16/32 |

| Diamonds Contract |

7/14/28 |

| Clubs Contract |

6/12/24 |

So a contract of, say, 3 of diamonds is worth 21 below-the-line points on its own (3 × 7 = 21). However, if the declarer wins ten total tricks on a contract of 3 of diamonds, he instead scores 28 below-the-line points. The first team to score 30 points below the line wins the game. The first side to win two games earns a 250-point rubber bonus.

If the declarer makes a doubled contract, he scores above-the-line bonuses: 50 points for the contract, plus 50 points for each overtrick won in excess of the original contract. Redoubled contracts score 100 points for contract, 100 points for overtricks. Score a 50 point above-the-line bonus for small slams, 100 points for grand slams.

When the declarer loses the contract, the opposing teams scores 50 points above the line for each undertrick (100 points per trick if the contract is doubled; 200 points per undertrick if the contract is redoubled).

The side holding the majority of honors earns above-the-line bonus points, regardless of which team is the declarer. In trump contracts, the honors are A, K, Q, J, 10; in no-trump contracts, the honors are all four aces. The honors bonus is:

30 points: three honors

40 points: four honors, divided

50 points: five honors, divided

80 points: four trump honors in one hand

90 points: four trump honors in one hand, fifth honor in partner’s hand

100 points: four aces in one hand for no trump contracts

100 points: five honors in one hand

A BRIEF HISTORY All Bridge games are descendants of Whist. In 1905, Whist enthusiasts in London, New York, and Boston codified a new form of the game, called Auction Bridge. In 1926, the millionaire Harold Vanderbilt tinkered with the game’s rules on a Caribbean cruise and singlehandedly invented Contract Bridge. Enter Ely Culbertson and his wife (an Auction Bridge teacher), Josephine Dillon. They took Contract Bridge and turned it into an international phenomenon in the 1930s and ’40s, making and losing many millions of dollars along the way.

A BRIEF HISTORY All Bridge games are descendants of Whist. In 1905, Whist enthusiasts in London, New York, and Boston codified a new form of the game, called Auction Bridge. In 1926, the millionaire Harold Vanderbilt tinkered with the game’s rules on a Caribbean cruise and singlehandedly invented Contract Bridge. Enter Ely Culbertson and his wife (an Auction Bridge teacher), Josephine Dillon. They took Contract Bridge and turned it into an international phenomenon in the 1930s and ’40s, making and losing many millions of dollars along the way.