CALLOWAY, BLANCHE DOROTHEA JONES

(February 9, 1902–December 16, 1978) Singer, band leader, entrepreneur

An active participant in the Harlem Renaissance, Blanche Dorothea Jones Calloway became popular in the 1920s when she joined the national tour of the all-black musical revue Plantation Days, featuring Florence Mills, her idol since childhood. She was also inspired by blues singer Ida Cox. She moved to Chicago in 1927, and, between 1931 and 1938, formed, led, and directed her own orchestra, becoming the first woman to lead an all-male orchestra. She became one of the most successful bandleaders of the 1930s.

Calloway was born in Baltimore, one of four children born to Cabell Calloway, a lawyer, and Martha Eulalia Reed, a music teacher. She was the older sister of bandleader Cab Calloway, an icon of the Harlem Renaissance. She studied piano during her childhood and, in her teens, sang with a church choir. Calloway enrolled in Morgan State College (now University) in Baltimore but dropped out of school in the early 1920s to develop her interest in show business and a musical career that lasted fifty years.

While in Baltimore, Calloway performed in local nightclubs, revues, and stage shows. In 1921, she performed with Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle of Harlem Renaissance fame in the musical Shuffle Along. Her career blossomed when she joined and toured with the revue Plantation Days. When the show ended in 1927, Calloway remained in Chicago, which, by then, had become the jazz music capital. Blanche introduced her brother Cab to the entertainment world, and for a time they had their own act; he was bandleader and she was vocalist. Blanche became a popular attraction in clubs and also toured and performed at venues like the Crib Club in New York. She performed to packed houses in Atlantic City, Boston, Kansas City, New York, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis. Calloway’s all-male band performed at the Lafayette Theater in New York in 1931, 1932, and 1934, and at the Apollo Theater in 1935, 1936, 1937, 1938, and 1941. Race records became a public craze, which, in 1925, led her to record two records with her new group, Blanche Calloway and Her Joy Boys. They recorded “Lazy Woman Blues” and “Lonesome Lovesick Blues.” Her group featured some of the emerging young talent of the day, for instance, trumpeter Louis Armstrong and drummer William Randolph “Cozy” Cole. Calloway eventually renamed her group Blanche Calloway and Her Orchestra and led them to be considered one of the nation’s best musical groups.

The racially segregated and male-dominated musical world contributed to Calloway’s downfall. While on tour in Yazoo, Mississippi, in 1936, she used a ladies room at a local service station, and she and an orchestra member were then jailed for disorderly conduct. Her team abandoned the band. Her flamboyant performance style was considered inappropriate for female performers. By the mid-1930s, Calloway had difficulty getting bookings. In 1940, she assembled an all-girl orchestra, but the group was unsuccessful. After that, she settled in Philadelphia with her husband, became a socialite, and engaged in community activities before relocating to Florida in 1953. Calloway became a disc jockey in the 1950s and then founded a cosmetics company. She remarried in the last year of her life and returned to Baltimore, where she died of breast cancer.—Jessie Carney Smith

CAMPBELL, HAZEL VIVIAN

(1935–?) Short story writer

Hazel Vivian Campbell is best known for the two short stories that were published in Opportunity, a prominent African American magazine. One of the foremost mediums that operated during the dazzling Harlem Renaissance era, the magazine featured the literary works of male and female writers. Although some writers rose to prominence, for example, Zora Neale Hurston, many others, like Campbell, did not attain far-reaching success and notoriety. Consequently, little is known about Campbell.

Campbell’s short stories are significant in that they narrate the sobering realities of poverty and struggle in black life. Her first short story, “Part of the Pack: Another View of Night Life in Harlem,” was published in the Opportunity in August 1935. “The Parasites” was published in September 1936. In “Part of the Pack,” a couple grapples with poverty, unemployment, and a race riot, issues and events that loomed even during the glamorous days of the Harlem Renaissance. In “The Parasites,” a family contends with welfare and the wretchedness of their living environment. Both stories are featured in Judith Musser’s anthology, “Tell It to Us Easy” and Other Stories (2008). This seminal anthology includes the complete short stories of women that were published in Opportunity magazine between 1923 and 1948.—Gladys L. Knight

CARTER, EUNICE HUNTON

(July 16, 1899–January 25, 1970) Lawyer, community leader, women’s rights advocate

During the Harlem Renaissance and years thereafter, the African American community in New York and New Jersey benefitted from the work of Eunice Hunton Carter. She had a keen interest in equal rights for women and government reform. As a social worker, she served many family service agencies before taking her degree in 1932 from Fordham University School of Law.

The Atlanta-born Carter was the daughter of William Alphaeus Hunton, an executive with the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), and Addie Waites Hunton, a field worker for the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA). The Atlanta race riots of 1906 spurred the Huntons to relocate to Brooklyn. Carter graduated from Smith College in 1921, with both bachelor’s and master’s degrees. With an interest in government reform, her master’s thesis is entitled “Reform of State Government with Special Attention to the State of Massachusetts.” She spent the next eleven years in public service. In 1924, she married Lisle Carter, a practicing dentist in New York.

Carter was admitted to the New York bar in 1934, and had a brief tenure in private practice but continued her interest in civic organizations and Republican politics. She joined the National Association of Women Lawyers, National Lawyers Guild, New York Women’s Bar Association, and Harlem Lawyers Association. She held membership in these organizations between 1935 and 1945. After the Harlem riots in 1935, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia named her secretary of the Committee on Conditions in Harlem. Carter also investigated rackets and organized crime in Harlem, having been named to an extraordinary grand jury by special prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey. She was the only black and the only woman on the investigative committee. From 1935 to 1945, Carter was deputy assistant district attorney for New York County, and she distinguished herself as a trial prosecutor.

In 1945, Carter returned to private practice and devoted much of her time to working with civic and social organizations, and seeking to secure equal rights for women. Her friendship with school founder Mary McLeod Bethune led her to become a charter member of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW), which Bethune and twenty other women founded in 1935. Carter was a member of the executive board and a trustee of NCNW. She held membership in many other organizations, including the Roosevelt House League of Hunter College, Urban League, and International Conference of Nongovernmental Organizations of the United Nations. She attended conferences held in foreign countries and held such posts as advisor to women in public life for the German government. Like her parents, she had a keen interest in YMCA work. She was a member of the YWCA national board, as well as the Administrative Committee for the Foreign Division, and cochair of its Committee on Development of Leadership in other Countries.

Carter retired from law practice in 1952, but her interest in women’s organizations and equal rights for women never waned. After a few months’ illness, she died in New York City.—Jessie Carney Smith

CASELY-HAYFORD (AQUAH LALUAH), GLADYS MAY

(May 11, 1904–1950) Poet

Gladys May Casely-Hayford, African by birth, contributed her poetry to the literary movement in Harlem in the 1920s and 1930s and further expanded, through her work, such themes as the strong sense of African cultural beauty and strength, as well as a feminist perspective inclusive of her own personal and sexual honesty. She was born on May 11, 1904, in Amix, Gold Coast, to parents who were activists in their community. Her father, Joseph E. Casely-Hayford, was a Pan-Africanist and a lawyer, and her mother, Adelaide Smith Casely-Hayford, was a Victorian feminist and educator. Although born with a malformed hip joint that resulted in being slightly lame in one leg, Casely-Hayford was not limited by this affliction. She spent her early years of education in Ghana and went to college at Colwyn Bay College in Wales, England.

Casely-Hayford’s interest in poetry began at an early age, fostered by her love of reading. At fifteen, she wrote a poem entitled “Ears,” which garnered much attention from the school’s headmistress and resulted in a call to her mother about this accomplishment. After completing her college education, she returned home in 1926, and taught African literature and folklore at her mother’s Girls Vocational School in Freetown, Sierra Leone. In 1927, after sending some of her poetry to Columbia University and having three of her poems published in Atlantic Monthly, thanks to her mother sharing her poetry with a friend in Cambridge, Casely-Hayford received an invitation to attend both Columbia University and Radcliffe College. Although she never made it to New York, her work was so impressive that it was published in such periodicals as Crisis, Opportunity, and the Message, and it was included in Countee Cullen’s book Caroling Dusk in 1927. Her most noted poems are “Creation” (1926), “Nativity” (1927), “Rainy Season Love Song” (1927), and “The Serving Girl” (1941).

Casely-Hayford’s poetry, published in the early years under the pseudonym Aquah LaLuah, was highly sought after, as it incorporated strong and beautiful African images and spoke directly about issues of women with an air of political sophistication. As an African writer who shared such pride in her homeland and a personal honesty about her experiences, her work had a direct effect on the literary works of African Americans from the 1920s through the 1940s as they sought a connection with their African heritage. Casely-Hayford spent most of her life in Sierra Leone, having later married and given birth to a son. While serving as caretaker for her mother and raising her son, she died in 1950, from black water fever or cholera.—Lean’tin L. Bracks

CATO, MINTO [LA MINTO CATO]

(August 23, 1900–October 26, 1979) Opera singer, producer, performer

Minto Cato was a mezzo-soprano opera singer who became known for performing show music during the Harlem Renaissance from the 1920s until the late 1940s.

Cato was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, in the late summer of 1900. She received musical training at the Washington Conservatory of Music, in Washington, D.C., and began her career by teaching piano in public schools in Arkansas and Georgia. In 1919, she opened a music studio in Detroit.

Cato began to work in show business at Detroit’s Temple Theater in 1922, when she performed with the B. F. Keith vaudeville circuit. She worked and toured with impresario Joe Sheftell, and they were married around 1923. She gave birth to a daughter, Minto Cato Sheftell, around 1924. During the 1920’s, Cato performed in many of Sheftell’s shows, including the Creole Bronze Revue. They conducted a worldwide tour of Europe, Alaska, Canada, and Mexico as the Southland Revue.

By the end of 1927, Cato had separated from Sheftell and was working in various venues. She had a solo act in 1929, at Chicago’s Regal Theater and worked as an impresario with such shows as the Frivolities of 1928. She also worked as a vaudeville producer in the United States and abroad. Cato was a successful singer, and she performed with Louis Armstrong in the Blackbirds shows from 1920 to 1930. In May 1936, she performed in the role of Azucena in the opera Il trovatore, which she also staged and directed. She went on to perform in many operas, singing the role of Aida with the Hippodrome Opera Company in New York. In 1938, Cato sang the role of Queenie in Show Boat and Liza in Gentlemen Unafraid with the Municipal Opera Society of St. Louis. Cato performed in La traviata with the National Negro Opera Company in 1947, and this was one of her last major opera performances.

In the mid-1940s, Cato returned to show business performances, but her career in the United States was in a state of decline, in part because the opera world was not offering roles to African American performers at this time. She returned to Europe and toured as part of a trio and a solo performer until the early 1950s. As the years passed, Cato remained active with the National Association of Negro Musicians. After her death in 1979, she was buried in Hawthorne, New York.—Faye P. Watkins

CAUTION-DAVIS, ETHEL [ETHEL M. CAUTION]

(1880–1981) Poet

As African American women began to follow their passion in the world of poetry, Ethel Caution-Davis was among those who had the talent and determination to add her work to the diverse poetry of the Harlem Renaissance era. Ethel M. Caution was born in 1880, in Cleveland, Ohio. After the death of her parents, she was adopted and later took on the surname Davis. Caution began her work in poetry while attending Wellesley College.

While in college, Caution produced short poems and essays that were published in Wellesley Magazine and Wellesley News. After graduating from college in 1912, she began to use the name Caution-Davis. She began her work experience as a teacher in Durham, North Carolina, and later taught in Kansas City, Kansas, before accepting a position as dean of women at Talladega College in Alabama. After three years, Caution-Davis moved back to the Northeast and then took up residence in New York, working for the public assistance program. She remained in New York until her retirement and continued to work with programs that helped single women.

Caution-Davis produced only a limited amount of poetry, but it was favorably received and published in such periodicals as Crisis, the Durham Advocate, and The Brownies’ Book for children. Her most notable poem, “Long Remembering,” is known for its complexity and a regard for showing diverse experiences. In her later years, Caution-Davis was nearly blind, but she kept up with literature and issues of the day through a volunteer reader and audio books. She died at 101 years of age in New York City.—Lean’tin L. Bracks

CHAPPELLE, JUANITA STINNETTE

(June 3, 1899–June 4, 1932) Singer

Juanita Stinnette was a vaudeville performer, as well as coproducer of the Chappelle and Stinnette Revue and the Chappelle and Stinnette record label during the Harlem Renaissance era. In 1912, Stinnette toured with Salem Tutt Whitney and Homer Tutt’s Smart Set Company, a vaudeville and musical comedy act. She later married the man that convinced her to join the show, Thomas Chappelle. The couple toured together for several years and, by 1922, had their own revue, the Chappelle and Stinnette Revue. The couple starred as a dancing team in such revues as Yaller Gal (1924) and Kentucky Sue (1926). Music was provided by the Jazz Hounds, who included Bobby Lee, Percy Glasco, Seymour Errick, and Fleming and Faulkner. In 1926, the couple produced nine blues discs under their label Chappelle and Stinnette, manufactured by C&S Phonography Record Company. The song “Decatur Street Blues,” by Clarence Williams, is the only song recorded that was not sung by the duo. Chappelle also appeared in a few Broadway shows, including How Come? (1923), Deep Harlem (1929), and Sugar Hill (1931). Chappelle died of peritonitis the day after her thirty-third birthday in 1932.—Amanda J. Carter

CLARK, MAZIE EARHART [FANNIE B. STEELE]

(1874–1958) Poet

Mazie Earhart Clark was a poet who published poems and collections of poetry during the Harlem Renaissance. Born in Glendale, Ohio, to David and Fannie Earhart, she lost her mother at the age of five. As a young adult, she studied chiropody in Cincinnati. She later opened a shop and married George Clark, a U.S. Army sergeant; he died in 1919. She experienced another loss with the death of her sister.

Poetry and religion, however, helped Clark transcend her sorrow. Although a lesser-known poet, she was a copious writer. Her poems were published in several periodicals. Notable collections include Life’s Sunshine and Shadows (1929), published under the pseudonym Fannie B. Steele, and Garden of Memories (1932). Her poems address assorted themes, including romantic love, patriotism, nature, religion, and family. Some poems also cover African American life and themes about southern living.—Gladys L. Knight

CLIFFORD, CARRIE WILLIAMS

(1862–November 1934) Writer, editor, educator, clubwoman, civil rights and women’s activist

Prior to and during the Harlem Renaissance, Carrie Williams Clifford worked to abolish racial and gender discrimination through various organizations and publications. The daughter of Joshua and Mary Williams, Clifford was born in Chillicothe, Ohio, in 1862. The family moved to Columbus, Ohio, when Clifford was approximately eight years old, and she attended the city’s public schools. She was a schoolteacher in Parkersburg, West Virginia, prior to her marriage to William H. Clifford, a lawyer and Republican state legislator, in 1886. They resided in Cleveland, where their two sons were born, until 1908. The family moved to Washington, D.C., after Clifford’s husband accepted employment as an auditor at the War Department.

Clifford’s earliest efforts to battle racial and gender discrimination were visible through her work with the National Association of Colored Women in the late 1890s, and the Ohio Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs (OFCWC), which was founded in 1900, with Clifford as the organization’s first president. Clifford edited the OFCWC’s Sowing for Others to Reap: A Collection of Papers of Vital Importance to the Race (1900). Active in national and local activities of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, she presented (along with Mary Church Terrell) the organization’s antilynching resolutions to President William Howard Taft in 1911.

Clifford published two volumes of verse. Her first book, Race Rhymes (1911), was published 138 years after Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773), and fifty-four years after Frances E. W. Harper’s Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects (1854). Thus, following in the tradition of Wheatley and Harper, Clifford was one of the first black women to publish a book of poetry. In addition, she was one of the first African American women to publish a volume of verse during the Harlem Renaissance, for her second book, The Widening Light (1922), was published four years after Georgia Douglas Johnson’s The Heart of a Woman (1918) and the same year as Johnson’s Bronze: A Book of Verse. Clifford’s poems were vehicles for her to protest racial and gender injustice, as well as pay tribute to notable African Americans. Both volumes were published posthumously as The Widening Light (1971). Clifford died in Washington, D.C.—Linda M. Carter

CLOUGH, INEZ

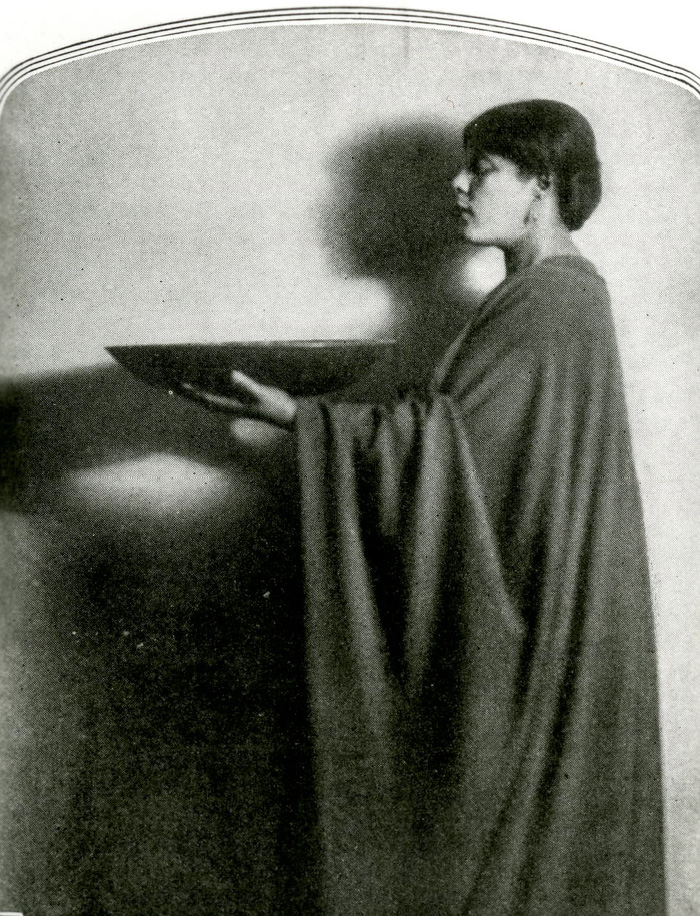

(c. 1860s or 1870s–November 24, 1933), Singer, dancer, actor

Inez Clough

The first black show to appear in a legitimate theater rather than a burlesque theater was John Isham’s Oriental America. When it opened on Broadway in 1896, Inez Clough was among its cast, and she toured with the show in the United States. Her work on the musical stage continued through the most productive years of the Harlem Renaissance.

Clough’s date and place of birth are uncertain. She was born in the 1860s or 1870s, probably in Worcester, Massachusetts. Little is known about her family. After Oriental America opened, Clough and the company went to London in 1897. Although the company disbanded in 1898, Clough remained in London until 1902. When she returned to New York, she joined the Bert Williams and George Walker’s company until 1911, and appeared in the troupe’s performances of In Dahomey (1902–1904), Abyssinia (1906–1907), Bandanna Land (1908–1909), and Mr. Lode of Koal (1909). In 1906, she toured with Cole and Johnson Brothers’ Shoo-Fly Regiment. Clough spent several years in vaudeville, ending such engagements when she became a member of the Lincoln Stock Company in New York, and later a charter member of the Lafayette Players.

During the most productive years of the Harlem Renaissance, Clough was active in dramatic and musical productions, and she appeared in two movies, one in 1921, and another in 1932. She joined the road company of Shuffle Along in 1922, and two years later she appeared on Broadway in The Chocolate Dandies, with Josephine Baker, Valaida Snow, and Elizabeth Welch. Her other appearances included Earth (1927), Wanted (1928), and Harlem: An Episode of Life in New York’s Black Belt (1929). Clough retired from show business in the late 1920s and died in Chicago.—Jessie Carney Smith

COLEMAN, ANITA SCOTT

(November 27, 1890–March 27, 1960) Essayist, poet

During the height of the Harlem Renaissance, Anita Scott Coleman was a literary contributor from the Southwestern United States who won numerous prizes for her short stories, essays, and poems. She was born in Guaymas, Mexico, on November 27, 1890, to William Henry Scott, a retired Buffalo soldier in the well-known 9th Calvary Regiment, and Mary Ann Stokes. Coleman grew up on a ranch in New Mexico, matriculated from the New Mexico Normal School, and later began working as a teacher.

On October 16, 1916, she married James Harold Coleman, a printer and photographer originally from Virginia. She then ended her teaching career. She published her first writings while living in New Mexico from 1919 to 1925. Coleman published her first story, “Phoebe and Peter up North,” in Half-Century Magazine in 1919. During this time period, she published thirteen short stories. Her most famous story, “The Little Grey House,” was published in 1922.

Coleman relocated to Los Angeles to join her husband, who had moved there for work. In Los Angeles, where she lived from 1926 until her death in 1960, she raised four children, ran a boarding house, and published her most sophisticated work.

Despite living in New Mexico and later in Los Angeles, Coleman published numerous essays, short stories, articles, and poems in the major race journals advocating the uplift of the African American race, including Crisis, Messenger, Competitor, and Opportunity. She also published in several major African American newspapers, namely the Pittsburgh Courier, Nashville Clarion, and Messenger. Coleman, who won several literary prizes, knew many writers of the Harlem Renaissance era, including Langston Hughes and Wallace Thurman. She also corresponded with Countee Cullen, who was an assistant editor for Opportunity.

Coleman produced more than thirty short stories during the Harlem Renaissance period. Her best stories include The Brat and Three Dogs and a Rabbit. Although she never lived in Harlem, her work epitomizes the goals of the writers of that time. Her stories focus on racial pride and issues important to black women, and explore such issues as employment discrimination, lynching, and segregation.

Coleman died relatively unknown in Los Angeles in 1960; however, her writing was an important contribution linking the Southwest to the Harlem Renaissance. Her writings give us a glimpse into the lives of African Americans living in the Southwest during that time.—Andrea Patterson-Masuka

COLEMAN, BESSIE [ELIZABETH]

(January 26, 1892–April 30, 1926) Aviator

Early aviator Bessie Coleman is often associated with the Harlem Renaissance and its participants, perhaps due to the iconic role that she played in American aviation and the admiration that her race had for her notable accomplishments. In 1921, she was the first black American woman to become an aviator and gain an international pilot’s license. She was also the first black woman stunt pilot, or “barnstormer.” She joined the group of blacks who opposed racial segregation, especially during performances by blacks, and became a role model for women with an interest in aviation. For a brief period during the Harlem Renaissance, Coleman was widely promoted in the press as a popular heroine.

Born Elizabeth Coleman in Atlanta, Texas, Bessie, as she was popularly known, was the daughter of George Coleman, a day laborer of Indian descent, and Susan Coleman, a domestic. The family relocated to Waxahachie, Texas, but her father left the family and returned to the Indian Territory in Oklahoma that he knew. This left Susan to care for her family. After completing high school, Bessie spent one semester at Langston Industrial College (later Langston University) but dropped out due to financial problems. In 1917, she joined her two brothers in Chicago, studied manicuring at Burnham’s School of Beauty Culture, and worked at the White Sox Barber Shop. She later managed a small restaurant.

Coleman married Claude Glenn in 1917. Meanwhile, her brother Johnny told her stories about female pilots in France during World War I. An avid reader since childhood, she also read about aviation and thus developed an interest in the then-fledgling field. Determined to learn to fly and earn a pilot’s license, she sought admission to various aviation schools but was rejected due to her race and gender. Robert S. Abbott, founder and editor of the Chicago Defender, and black banker Jesse Binga became her staunch supporters and provided the finances needed to study aviation in France, where female aviators were encouraged. Coleman accepted their support, learned French, and was trained at the School of Aviation in Le Croto, the most famous flight school in France. She had both French and German aviators as her teachers.

The French Federation Aéronautique awarded Coleman international pilot’s license number 18310 on June 15, 1921, making her the first black woman to hold such recognition; this was only ten years after the first American woman had earned her pilot’s license. She returned home in September 1921, but left again for Europe for advanced training in stunt performance and parachute jumping. She was back home in August 1922, with the continued sponsorship of Abbott, Binga, and the Chicago Defender.

Coleman’s first exhibition in the United States was at Garden City, New York, on Labor Day 1922, when she flew a Curtiss aeroplane. By this time, she owned three army surplus Curtiss biplanes and performed in the Chicago region in October of that year. She also gave successful exhibitions throughout the Midwest. Coleman met David Behncke during her third exhibition in Gary, Indiana. Behncke, president of the International Airline Pilots Association, became her manager. During Coleman’s first exhibition flight on the Pacific Coast, flying from Santa Monica to Los Angeles, her engine failed and her plane was demolished when it fell 300 feet to the ground. As Coleman recuperated, she went on a lecture tour.

Her performances continued, as she performed in Columbus, Ohio, Memphis, Tennessee, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and elsewhere. When she performed, she drew large crowds and thrilled spectators as much with her flying outfit (cap, helmet, goggles, long jacket, and pants) as with her skill. She became known as “Brave Bessie.” Coleman endured another airplane accident while flying from San Diego to Long Beach and, as before, lectured to churches and schools while recuperating. As often as she could, she lectured on the opportunities for blacks, including black women, in aviation. She also appeared in many news documentaries during this time.

An invitation from the Negro Welfare League brought Coleman to Jacksonville, Florida, in April 1926, to perform in an airshow for the upcoming First of May celebration. When she learned that blacks were forbidden to attend her show, she refused to perform. Because local agencies refused to rent a plane to blacks, she decided to use her Jenny plane instead. After the flight from Texas to Jacksonville, her plane developed mechanical problems during a practice run, and Coleman fell out of the plane and to her death. She was highly celebrated at services following her death, and organizations and clubs have been formed and air shows held in her honor. Coleman is buried in Chicago’s Lincoln Cemetery. In 1995, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp in the Black Heritage Series honoring Coleman.—Jessie Carney Smith

COLE-TALBERT, FLORENCE

(June 17, 1890–April 3, 1961) Opera singer, educator

Florence Cole-Talbert

After deciding at the age of fifteen to be a become a singer, Florence Cole-Talbert went on to become the first African American to perform the challenging title role in Verdi’s Aida, the opera that inspired her decision. Her commitment to music also influenced her to teach and support the talents of other aspiring singers in their careers.

Born in Detroit, Michigan, on June 17, 1890, Cole-Talbert came from a family of musicians, her father a singer, basso, and dramatist reader, and her mother a singer and mezzo-soprano who traveled extensively with the Fisk Jubilee Singers and became well known for her talents. Once she decided to become a singer, Cole-Talbert attended high school in Los Angeles. After participating in her school’s music programs and graduating, she completed her college degree at Chicago Musical College in 1916. She briefly married Wendall Talbert, and after their relationship ended she decided to keep his surname for professional reasons.

Between 1918 and 1925, Cole-Talbert accomplished a great degree of success. She made her New York debut concert appearance on April, 18, 1918, at Acolian Hall, and continued to make appearances in Detroit, Los Angeles, and throughout the United States. As a well-received performer, she had excellent reviews in the local papers. Cole-Talbert also recorded on several record labels. These included Broome Special Phonograph, created to support the work of black artists; the Paramount label; and the Black Swan label. In 1925, Cole-Talbert decided to embark on a two-year stay in Europe for additional vocal study, which included her singing the title role in Aida at the Teatro Comunale, in Consenza, Italy. Although Italian audiences were known for their strong and sometimes negative responses to performances, Cole-Talbert was triumphant and given critical acclaim for her role.

Cole-Talbert returned to the United States in 1927, married Dr. Benjamin F. McCleave, and became stepmother to his four children. She continued to do recitals until 1930, when she accepted a position as music director at Bishop College in Dallas, Texas. Throughout the years, she also had teaching positions at Fisk University, Tuskegee Institute, and Alabama State College. She mentored aspiring students during her career, most notably Vera Little, a mezzo-soprano who debuted as Carmen in Berlin, Germany, in 1957, and Marian Anderson, whom she encouraged and further helped by raising funds with a concert for Anderson’s voice training.

Cole-Talbert remained active in the music world and served in the National Association of Negro Musicians and the Memphis Music Association. She served as an example to many who faced the challenges and barriers of being the first to achieve in areas where black Americans were not known and not always welcomed. Cole-Talbert, a pioneer for black concert artists, died in Memphis, Tennessee.—Lean’tin L. Bracks

COOPER, ANNA JULIA HAYWOOD

(August 10, 1858–February 27, 1964) Educator, writer, feminist, activist

Prior to, during, and after the Harlem Renaissance, Anna Julia Haywood Cooper improved the quality of life for generations of African Americans, as she obdurately and persistently challenged prevailing notions of African American intellectual inferiority and gender discrimination. She was born in Raleigh, North Carolina, on August 10, 1858, to Hannah Stanley, a slave, and George Washington Haywood, a slaveholder. In 1868, she was a member of the inaugural class at St. Augustine’s Normal School and Collegiate Institute (now St. Augustine’s University), where she received her primary and secondary education. Cooper earned her bachelor’s degree in 1884, and her master’s degree in 1887, from Oberlin College, as well as her Ph.D. from the University of Paris (Sorbonne) in 1925. Her two-year marriage to George Cooper, who was the second African American ordained as an Episcopal minister in North Carolina, ended with his death in 1879. Decades later, Cooper, at the age of fifty-seven, adopted five children, ranging from infancy to twelve years, who were the grandchildren of her half-brother, and raised them in Washington, D.C.

Cooper’s career as an educator (teacher and administrator) lasted more than seventy years. She exhibited pedagogical promise as a child at St. Augustine’s when she tutored other students. Upon graduating from St. Augustine’s, she taught at the school prior to her matriculation at Oberlin. After she received her Oberlin degrees, she taught at Wilberforce College in 1884, and returned to Saint Augustine’s in 1885. Two years later, Cooper joined the faculty of the Preparatory High School for Colored Youth (renamed M Street High School in 1891, and then Dunbar High School in 1916) in Washington, D.C., where she was appointed principal in 1902. During her tenure, a number of M Street students were accepted to Ivy League institutions; however, when Cooper refused to deemphasize academics in favor of manual training, racism and sexism led to her dismissal in 1906. Cooper taught at Lincoln University in Missouri until 1910, when she returned to M Street and taught until 1930. That same year, Cooper, who was in her early seventies, was appointed president of Frelinghuysen University, located in Washington. After Frelinghuysen lost its building lease, Cooper allowed classes to be held in her home. She remained president until 1941, and then served as Frelinghuysen’s registrar until the mid-1950s.

Cooper did not limit her efforts on behalf of her fellow African Americans to academe. She was also a prominent and prolific lecturer. At the 1886 meeting of African American Episcopal ministers in Washington, her discourse centered on womanhood and race; that lecture appears as the lead essay in her A Voice from the South, by a Black Woman of the South (1892), a landmark African American feminist publication by a woman who challenged gender discrimination as early as her days as a student at St. Augustine’s, and subsequently as an undergraduate at Oberlin College. In 1893, Cooper lectured on the intellectual advancement of African American women at the Congress of Representative Women at the World’s Fair in Chicago. She addressed African American issues at the first Pan-African Conference, which was convened in London in 1900. She also lectured at the 1895 National Conference of Colored Women in Boston, the 1896 National Federation of Afro-American Women in Washington, and the 1902 Biennial Session of Friends’ General Conference in Asbury Park. In addition to her activities as an educator and lecturer, Cooper was a founder of the Colored Women’s League of Washington in the late nineteenth century, and the Colored Women’s Young Women’s Christian Association in the first decade of the twentieth century. She was also a trustee of the Colored Settlement House, founded in 1905, and situated in Washington. In addition, she was the Women’s Department editor for the African American magazine Southland, founded in 1890. Aside from the aforementioned A Voice from the South, Cooper’s publications include her memoir, The Third Step (c. 1945), as well as the two volumes Personal Recollections of the Grimké Family (1951) and The Life and Writings of Charlotte Forten Grimké (1951). Cooper’s 1925 dissertation, written in French, was translated by Frances Richardson Keller and published in 1988 as Slavery and the French Revolutionists (1788–1805). The educator, writer, and activist died in Washington.—Linda M. Carter

COPELAND, JOSEPHINE

(?–?) Poet

Josephine Copeland is best known for her poem “The Zulu King: New Orleans,” which contains her unique perspective of black life during the Harlem Renaissance. Born in Covington, near New Orleans, Louisiana, she moved to Chicago after completing a two-year teaching course at Dillard University in New Orleans. She published few poems in her lifetime but, nonetheless, left an indelible mark.

Although much of the literary works of this movement centered on life in the city or the South, Copeland added her intimate experience of life in her native Louisiana in her celebrated poem, “The Zulu King: New Orleans.” This poem was included in Arna Bontemps’s Golden Slippers (1941). New Orleans is known for its large African American population and distinct cultural traditions that meld influences of the Spanish, French, and Africans. Mardi Gras, a long-standing tradition in the city, is a celebration that is observed with floats, costumes, and much revelry. “The Zulu King” is Copeland’s ode to the Mardi Gras Carnival tradition and the pride that the Zulu-inspired float generated in her.

“The Zulu King” was Copeland’s second known published poem. Her first, “Negro Folk Songs,” was published in Crisis magazine in 1940. The poem describes the tragedy of black oppression and discrimination in four gripping stanzas.—Gladys L. Knight

COWDERY, MAE VIRGINIA

(1909–1953) Poet

Although not as familiar as other writers of the Harlem Renaissance, Mae Virginia Cowdery published numerous poems in popular black magazines during the 1920s. Encouraged by both Langston Hughes and Alain Locke, she submitted poems to Crisis, Opportunity, and other journals. Her works also appeared in anthologies containing works by such writers as Jessie Redmon Fauset and Zora Neale Hurston. Inspired by the work of Edna St. Vincent Millay, Cowdery became one of few black female poets of that time to publish an entire volume of her own works.

Born in Germantown, Pennsylvania, on January 10, 1909, Cowdery grew up in a family that valued the arts. Her father, Lemuel, worked as a caterer and post-office clerk. Her mother, a social worker, helped direct the Bureau for Colored Children. They enrolled Cowdery in a prestigious school for academically gifted students, the Philadelphia High School for Girls. There she began to develop her interests in literature and the visual arts.

In the spring of 1927, Cowdery’s senior year, Black Opals, a black literary journal based in Philadelphia, published three of her poems. That same year, she earned first place in a poetry contest sponsored by Crisis, and she also won the Krigwa Poem Prize. She belonged to Philadelphia’s Beaux Arts Club, a literary society that began in the 1920s and flourished during the next three decades. Cowdery went on to study design and the visual arts at New York’s Pratt Institute.

While in New York, she visited Harlem and Greenwich Village frequently, spending time in the cabarets. Langston Hughes, Alain Locke, Benjamin Brawley, and others encouraged Cowdery in her writing. Other contemporaries included Nellie Bright, Idabelle Yeiser, Evelyn Crawford Reynolds, Ottie Beatrice Graham, and Arthur Huff Fauset. Throughout the early 1930s, Crisis and Opportunity published many of Cowdery’s poems. Her work also appeared in Carolina Magazine and Unity. A January 1928 issue of Crisis includes a few of her poems and features a photograph of her on its cover. That year, Black Opals published her one-act play, Lai-Li.

Several of Cowdery’s poems were also published in anthologies, including Charles S. Johnson’s Ebony and Topaz, William Stanley Braithwaite’s Braithwaite’s Anthology, and Benjamin Brawley’s The Negro Genius. In 1936, she collected her works, publishing a limited edition volume (350 copies) entitled We Lift up Our Voices and Other Poems. In Braithwaite’s highly complementary introduction to the work, he characterizes Cowdery as a fugitive poet. Critics proved receptive to the work, some of them comparing her imagery to that of Angela Weld Grimké and other modernists. The book stands as Cowdery’s last published work. She committed suicide at the age of forty-four.—Marie Garrett

COX, IDA PRATHER

(February 25, 1896–November 10, 1967) Blues singer

Called a “Queen of the Blues,” the “Uncrowned Queen of the Blues,” and the “Blues Singer with a Feeling,” Ida Cox began performing as a child. By the time the Harlem Renaissance reached full swing, she had become a star solo performer. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Cox took her own road show on tour and did versions of Raisin’ Cain and Dark Town Scandals. She barnstormed throughout the South in the 1930s and into the 1940s, and often appeared with emerging musicians and performers.

Born Ida Prather in Tocca, Stephens County, Georgia, she spent some years in Cedartown, Georgia, and sang in the church choir. When only fourteen years old, she left home and toured under the names Velma Bradley, Kate Lewis, Julia or Julia Powers, Jane Smith, and other stage names. She appeared in blackface and played “Topsy” roles with the White and Clark Black and Tan Minstrels until 1910. She later appeared with the Rabbit Foot Minstrels, Silas Green Show, and Florida Cotton Blossom Minstrels. In 1916, Prather married Adler Cox and became known under the Cox name. After Adler Cox died in World War I, she married twice more.

Between 1923 and 1929, Cox recorded extensively with Paramount, producing seventy-eight titles. Lovie Austin and Her Serenaders joined her on early recordings; they were backed up by Coleman Hawkins, Fletcher Henderson, and others. Cox also recorded for both the Harmograph and Silvertone labels simultaneously.

In 1945, Cox suffered a stroke that slowed her performances tremendously, and she moved to Knoxville, Tennessee, with her daughter. Her performances between 1940 and 1960 were intermittent. In 1961, after spending time doing church work and a twenty-year hiatus from performances, Cox cut her final album, Blues for Rampart Street, backed up by Hawkins and other all-star band members. She suffered another stroke while living in Knoxville and died of cancer.—Jessie Carney Smith

CRIPPENS, KATHERINE “LITTLE KATIE” [ELLA WHITE]

(November 17, 1895–November 25, 1929) Entertainer

Katherine “Little Katie” Crippens was born on November 17, 1895, to John Crippens and Catherine Garden in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She had at least two siblings. As a teenager, she settled in New York and worked at Edmond’s Cellar, the cabaret club where Ethel Waters rose to fame. She married Lou Henry, who also was a musician. Crippens was also known as “Ella White.”

Crippens recorded with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra on the Black Swan label in 1921. It was Katie Crippens and Her Kids that gave the legendary William “Count” Basie one of his first musical opportunities. He was pianist of the group. Crippens also did various tours in the 1920s with Dewey Brown. She also operated her own food concession to bring in additional income.

Crippens died in 1929 after a long battle with cancer.—Jemima D. Buchanan

CUNARD, NANCY

(March 10, 1896–March 17, 1965) British poet, writer, publisher, journalist, activist

In regard to the Harlem Renaissance, the British-born Nancy Cunard is best known for her seminal contribution, the anthology entitled Negro (1934). Indeed, the anthology was, at the time of its publication, a groundbreaking work in that it features a comprehensive examination of the history of African Americans, their contributions and achievements, and the controversial issues of slavery, race, and racial injustice. The leading African American writers and intellectuals in Harlem praised her work, while the mainstream media vilified Cunard for her public support of African Americans. Cunard’s outspokenness in regard to unpopular topics and causes, as well as her scandalous reputation, made her an unconventional and complex figure. Nonetheless, she garnered respect from many in the Harlem community during the Harlem Renaissance and is remembered as a daring contributor to early twentieth-century African American literature.

Cunard was born in 1896, into a wealthy family. Her father, Sir Bache Cunard, was an heir to the Cunard Line shipping business. Her American-born mother, Maud Alice Burke, descended from a wealthy family. Nancy spent her early childhood on the family estate in Leicestershire and was mostly raised by maids and governesses. Her appetite for reading, poetry, and elite culture, for instance, the opera, was greatly influenced by her mother and novelist George Moore.

In 1911, Cunard moved with her mother to London after her parents separated. She obtained her formal education at elite European institutions in London, as well as France and Germany. Although her world was filled with parties and encounters with royalty and high society, she would not subscribe to conventional ideas concerning white superiority and supremacy with regard to marginalized groups. Such ideas were prevalent among the power elite.

While Cunard remained a part of this world, she also did as she pleased. She took different lovers throughout her life, only briefly settling into marriage in 1916. When jazz created by African Americans reached Europe, Cunard became enamored with the music. She wore African bracelets piled up on her forearms. Known for her beauty and status as a well-known socialite, she fascinated as much as she confounded mainstream society. She inspired poets, novelists, and artists, many of whom were her friends. She promoted literature through her small press, Hours Press, which she established in 1928. She fueled media coverage of her scandalous behavior, for instance, her taboo relationship with the African American jazz musician Henry Crowder.

After meeting and then forming a relationship with Crowder in the late 1920s, Cunard’s life was changed. Through Crowder, she was introduced to racism, discrimination, and racial violence in the United States. Her interest and desire for action spawned the anthology Negro. In this work, Cunard assembled mostly African American writers who contributed more than 800 pages of poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and historical documents. In addition to visits to Harlem, Cunard befriended such high-profile individuals as writer and Harlem Renaissance proponent Langston Hughes.

Cunard supported the literary development of African Americans, as well as their struggle for equality. Through such efforts as fund-raising and journalism, she fostered other causes, including protesting fascism in Spain.

When Cunard died in Paris, she left the world many works. These include poems; Black Man and White Ladyship (1931), a pamphlet that protests her mother’s disapproval of her relationship with Crowder; and such books as Grand Man: Memories of Norman Douglas (1954).—Gladys L. Knight

CUNEY HARE, MAUD

(February 16, 1874–February 13, 1936) Biographer, playwright, musician, musicologist, historian

Maude Cuney Hare became an influential figure in the Harlem Renaissance during the 1920s. She was a talented musician, a prolific author, and one of the first historians to investigate the African roots of American music. She also documented the performances and compositions of black women in music.

Cuney Hare was born in Galveston, Texas, on February 16, 1874, the daughter of Adelina Dowdie Cuney, a school teacher, and Norris Cuney, a prominent Texas politician. Norris was the son of a white plantation owner and Adeline Stuart, one of his slaves. Maude’s father served as an alderman, ran unsuccessfully for mayor of Galveston, and later became chairman of the Texas Republican Party. In 1889, Norris was appointed collector of customs for the port of Galveston.

Cuney Hare had a pale complexion and European features. She could have passed for white, but her equally light-skinned father made sure that she was proud to be an African American. Cuney Hare’s family was very affluent. She grew up in a comfortable home surrounded by books and music. After graduating from Central High School in Galveston in 1890, she traveled to Boston at the age of sixteen to study at the prestigious New England Conservatory of Music. After her arrival, some of the white students complained and pressured the school’s administrators to bar her from living in the dormitory. Cuney Hare’s father received a letter in October asking him to remove his daughter from the conservatory. Mr. Cuney promptly dispatched a response, flatly refusing to do so.

After learning about the matter, Boston’s Colored National League convened a meeting at the Charles Street A.M.E. Church. The attendees adopted a forceful resolution condemning the conservatory’s actions and noting that discrimination against students based on their race was prohibited by Massachusetts law. They delivered the resolution to the conservatory and demanded just treatment for the young girl. W. E. B. Du Bois, who was a student at Harvard at the time, joined a group of students who supported Cuney Hare. The conservatory backed down, and Cuney Hare graduated in 1895.

After completing her studies at the conservatory, Cuney Hare enrolled in the Lowell Institute at Harvard University, where she studied English literature. She socialized with Boston’s circle of elite African Americans and was, for a while, engaged to marry Du Bois. The engagement did not last, but the two remained friends, corresponding regularly and collaborating on projects. Cuney Hare was one of the first women to join the Niagara Movement, a predecessor to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

In 1898, Cuney Hare returned to Texas, where she served as director of music at the Texas Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Institute for Colored Youths. In 1898, she married a physician, J. Frank McKinley, and moved with him to Chicago. The couple had one child, Vera, and divorced in 1902. Cuney Hare returned to Texas and worked for two years as a music instructor at Prairie View State College (now Prairie View A&M University). On August 10, 1904, she married William Parker Hare and returned to Boston. In 1908, Cuney Hare’s daughter from her previous marriage died at the age of eight.

Cuney Hare performed regularly in musical recitals and lectured extensively. She accompanied baritone William Howard Richardson on concert tours for almost two decades. She also performed with other distinguished singers. A folklorist and music historian, Cuney Hare was interested in the African connection to European and American music. She traveled to Mexico, Haiti, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands collecting folk songs and dances.

In 1913, she published a biography of her father, Norris Wright Cuney: A Tribune of the Black People. She edited a poetry collection, The Message of the Trees: An Anthology of Leaves and Branches, in 1918. She also authored Antar of Araby, a play about a black Arabian slave, poet, and warrior. In 1921, Cuney Hare wrote the book Six Creole Folk Songs. In addition, she contributed articles to Musical Quarterly, Musical Observer, Musical America, and the Christian Science Monitor. Cuney Hare wrote a regular column on music and the arts for Crisis, the NAACP’s widely circulated periodical.

In 1927, the playwright and musician established the Allied Arts Center in Boston to encourage the musical and artistic abilities of African American children. She continued to write, producing her best-known book, Negro Musicians and Their Music, in 1936. Cuney Hare’s research traced the evolution of African American music from its ancient African roots to the creation of jazz in the early twentieth century. She died of cancer in Boston shortly before her book was published.—Leland Ware

CUTHBERT, MARION VERA

(March 15, 1896–May 5, 1989) Educator, organization leader, writer, activist

Black women of the early twentieth century were circumscribed by race and gender prejudice, leading some, for example, Marion Vera Cuthbert, to seek relief and develop a commitment to equality and interracial harmony. Such conditions were very much behind the thinking of those who encouraged a renaissance in Harlem to celebrate and promote black talent. Cuthbert’s talent was also manifest in her advocacy for black women in the black academy and her work for justice through the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA).

Cuthbert was born to Victoria Means and Thomas Cornelius Cuthbert in Saint Paul, Minnesota. She earned a baccalaureate degree from Boston University in 1920; a master’s degree in 1931, from Columbia University; and doctorate from Columbia University’s Teachers College in 1942. After teaching English and serving as assistant principal at Burrell Normal School in Florence, Alabama, Cuthbert left in 1927, to become dean of women at historically black Talladega College in Talladega, Alabama. She was present on March 1–2, 1929, at a historic conference at Howard University that gave birth to the Association of Deans of Women and Advisers to Girls in Negro Schools.

Cuthbert left Talladega in 1932, to take a leadership position with the national YWCA, where she helped guide others in leadership training. She conducted workshops on interracial relations in the United States and several foreign countries. Cuthbert blossomed as a writer in the 1920s while with the YWCA. She contributed articles to Woman’s Press, the official publication arm of the association, and YMCA Magazine, and collaborated on the organization’s numerous training publications. Her writings include a biography of Fisk University’s dean of women Juliette Derricotte, entitled Juliette Derricotte (1933); We Sing America (1938); a book of children’s stories; April Grasses (1936); and Songs of Creation (1949). Cuthbert’s essays, poetry, short stories, and book reviews regularly appeared in periodicals from the 1930s through the 1960s. Her works deal with YWCA matters, education, black women, race relations, religion, social issues, and other then-timely topics.

Cuthbert continued to work in YWCA leadership but also returned to academia in 1942, when she joined the Brooklyn College Department of Personnel Services. She retired in 1961, moved to Plainfield, New Hampshire, and became an integral member of the community. She held membership in church organizations and lectured to groups about social issues and her new books. She moved to Concord, New Hampshire, in 1968, and then to Windsor, Vermont, and Claremont, New Hampshire.—Jessie Carney Smith