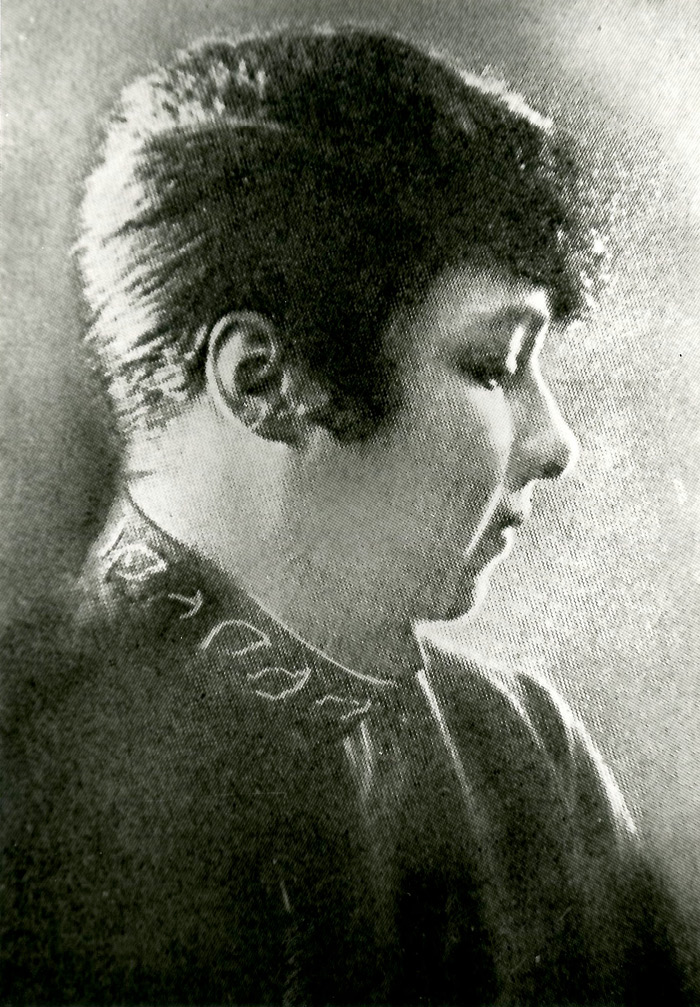

WALKER, A’LELIA [LELIA MCWILLIAMS]

(June 6, 1885–August 15, 1931) Entrepreneur, socialite

A’Lelia Walker

Skilled businesswoman A’Lelia Walker was not only the daughter of beauty industry pioneer Madame C. J. Walker and heiress to her hair care fortune, she was also an advocate for the arts and a socialite who brought together artists during the Harlem Renaissance, including poet Langston Hughes, author Zora Neale Hurston, actor Paul Robeson, and writer and photographer Carl Van Vechten.

Born Lelia McWilliams in Vicksburg, Mississippi, on June 6, 1885, Walker was the only child of Moses and Sarah Breedlove McWilliams. After the death of Moses in 1887, Sarah moved with her daughter to St. Louis, Missouri, where three of the Breedlove brothers ran a barbershop.

The McWilliams’s transition to city life was aided by ladies from St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church, whose association with the National Association of Colored Women helped them better understand the plight of newcomers to the city. One of the women, Maggie Rector, matron of St. Louis Colored Orphans’ Home, helped enroll Lelia in Dessalines Elementary School in 1890. In 1894, Sarah married John Davis, who was an abusive alcoholic from whom she was separated by 1903. Determined that her daughter have a solid chance at success, she saved enough of her washerwoman’s salary to send Lelia to Knoxville College in 1902, right before she began working on her hair care product formulas.

In 1905, Sarah moved to Denver to become a sales agent for Annie Malone’s Poro Company, a hair care products manufacturer that would later become a lifelong rival. One year later, Sarah married Charles Joseph Walker and began the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company in Denver, Colorado. Lelia soon joined her family in Denver to become one of the company’s first employees, where she learned beauty culture and the hair-growing process. While she was not formally adopted by her mother’s third husband, Lelia took the Walker name to establish and validate her connection to the family business. By September 1906, she had taken over the Denver mail-order operation, while her mother and stepfather traveled throughout the Southern and Eastern United States to promote the business. By 1908, Madam Walker had established the Lelia College of Hair Culture and a temporary headquarters in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, at which point Lelia moved east to become one of the company’s first traveling sales agents.

In 1909, Lelia married John Robinson, a laborer, and became known as Lelia Walker Robinson. He left her within one year of their marriage, although they would not officially divorce until 1914. Madam Walker opened her permanent headquarters in Indianapolis, Indiana, in early 1910, so Lelia took over the Pittsburgh operation of the beauty school and sales agents’ supply station.

During a visit with her mother in Indianapolis in 1911, Lelia was introduced to twelve-year-old Fairy Mae Bryant, whose long hair enabled her to be an ideal model for Madam Walker’s hair care products and treatments. By October of the next year, the Walker women had adopted the child from her widowed mother, Sarah Etta Bryant, on the condition that she be formally educated and receive business training. Lelia changed the child’s name to Mae Walker Robinson. Mae graduated from Spelman College in 1920, and became president of the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company upon Lelia’s death in 1931.

By 1913, Harlem was just beginning to embody the African American political, social, cultural, and artistic mecca later known as the Harlem Renaissance. Seeing this, Walker convinced her mother to start a branch office on 136th Street, near Lenox Avenue in New York City, where they opened Walker Hair Parlor and Lelia College of Hair Culture. Walker oversaw the six-week training course at the college and managed the northeastern sales territory. During World War I, Walker followed her mother’s lead in supporting black troops by hosting fundraisers and volunteering with the Colored Women’s Motor Corps as an ambulance driver for formal occasions and parades honoring the troops. In 1917, Madam Walker hired Alpha Phi Alpha founder and one of the first licensed African American architects in New York, Vertner Woodson Tandy, to build a thirty-four-room limestone and brick Georgian-style mansion at Irvington-on-Hudson, New York. Walker’s friend, opera singer Enrico Caruso, dubbed it “Villa Lewaro,” based on the first two letters of Walker’s name, Lelia Walker Robinson.

When Madam Walker passed away on May 25, 1919, Lelia became president of the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company and inherited most of her mother’s estate. Days after her mother’s funeral, Walker married Wiley Wilson, a Howard University Medical School graduate. As with her first marriage, they separated within a year after allegations of an affair with his former girlfriend, but the duo did not divorce until 1925.

A seasoned international traveler to Central America, the Caribbean, and Hawaii, Walker left in November 1921 to spend five months in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. During the trip she visited London’s Covent Garden; attended the coronation of Pope Pius XI in Rome; toured the Egyptian pyramids on camelback; and is said to be the first American to meet Ethiopian empress Waizeru Zauditu, daughter of the emperor who defeated an invading Italian army in 1896. Upon her return to the United States in 1922, and for unknown reasons, Walker changed her first name to A’Lelia.

In 1923, Walker began orchestrating a lavish wedding for her daughter. Walker chose Dr. Gordon Jackson to marry Mae in November of that year at the illustrious St. Philip’s Protestant Episcopal Church. She distributed more than 9,000 invitations and held an extravagant reception with elaborate decorations; however, the marriage was short. Mae Walker and Dr. Gordon Jackson divorced in December 1926. By August 1927, Mae had married Marion Rowland Perry Jr., an attorney.

Walker married her third husband in May 1926. James Arthur “Artie” Kennedy was a Chicago psychiatrist and later a physician, as well as second in command at the Tuskegee Veterans Hospital in Alabama. Walker donated $25,000 to the Hampton-Tuskegee Endowment Fund when he moved to Alabama. They agreed to live separately but only visited one another a few times before divorcing in March 1931.

Always a socialite, Walker began a tradition of “at-home,” where she would introduce her artist, writer, performer, and celebrity friends to one another. In October 1927, she converted one floor of her 136th Street townhouse into a literary salon, nightclub, and tearoom called the Dark Tower, based on Countee Cullen’s column in Opportunity magazine. The centerpiece of the room was a bookcase designed by Paul Frankl in the shape of a tower and filled with first-edition copies of some of the best African American writers of the day. Walker intended for it to be a place for writers, artists, and performers to congregate and socialize. Between the Dark Tower and her smaller pied-à-terre at 80 Edgecombe Avenue, she hosted such visitors as Langston Hughes, composer and pianist Eubie Blake, Zora Neale Hurston, dancer Florence Mills, and Paul Robeson, as well as white writers the likes of Carl Van Vechten, Witter Bynner, Muriel Draper, and Max Ewing. On some occasions guests included African and European royalty. Since she held parties for the famous and not-so-famous, Langston Hughes called her the “joy goddess” of the Harlem Renaissance. The Dark Tower officially closed in October 1928, but it remained a venue for parties and meetings and was even the site of the wedding reception of W. E. B. Du Bois’s daughter Yolanda to Countee Cullen.

Between 1927 and 1928, Walker Company trustees decided to build a million-dollar headquarters in Indianapolis, Indiana. Sales at the company were greatly affected after the Stock Market Crash of 1929, so Walker and the trustees were forced to auction off much of the contents of Villa Lewaro in November 1930. The results of the auction were less than satisfactory, so the next year the townhouse was put on the market to be sold. In 1932, Villa Lewaro was sold at auction to Companions of the Forest. After later being sold back into private hands, the townhouse eventually became a historic landmark.

On August 15, 1931, after a champagne and lobster celebration for a friend in Long Branch, New Jersey, Walker died of a stroke at forty-six years of age. Yet, even her funeral was a grand event, much like the parties she hosted. More than 11,000 people viewed her in her silver, orchid-filled casket. Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Sr. presided and read her eulogy, Langston Hughes shared his poem “To A’Lelia,” and Hubert Fauntleroy Julian dropped bouquets of gladiolas and dahlias from a plane as her casket was lowered into the ground. Walker is buried next to her mother at Woodlawn Cemetery. Her daughter Mae became president of the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. The company itself survived into the mid-1980s.

While Walker lived in her mother’s shadow, the nearly six-foot-tall enthusiastic supporter of the arts was well-loved and created a social and cultural countenance of her own. She also established the role of the African American heiress. Walker’s memberships included the Harlem Child Welfare League, the Music School Settlement, and women’s auxiliaries of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the National Urban League. Langston Hughes writes of Walker in his autobiography that she was the inspiration for Duke Ellington’s Queenie Pie. Adora Boniface, a character from Carl Van Vechten’s Nigger Heaven (1926), is based on her, and sculptors, photographers, and artists who have rendered her likeness include Richmond Barthé, Augusta Savage, Berenice Abbott, R. E. Mercer, and James Latimer Allen.—Amanda J. Carter

WALKER, MADAM C. J. [SARAH BREEDLOVE]

(December 23, 1867–May 25, 1919) Hair products entrepreneur

Sarah Breedlove, who became known as Madam C. J. Walker, was a pioneering entrepreneur who laid the foundation for generations of African American women to own and operate hair care salons. She began her career in the cotton fields of Louisiana. She later worked as a washerwoman and moved up to cooking in kitchens. Within a few years, Breedlove launched what would become an international sales and manufacturing enterprise that would make her the wealthiest black woman in the United States. She was in Harlem when the cultural revolution was in bloom, and she and daughter A’Lelia became well noticed among the contributors of that period.

Breedlove was born on December 23, 1867, in Delta, Louisiana. Her parents were Owen and Minerva Breedlove. Sarah had a sister, Louvenia, and four brothers, Alexander, James, Solomon, and Owen Jr. Her parents had been slaves on a Parish farm in Louisiana. In 1874, Minerva died during a yellow fever epidemic. The following year, Owen died from the same disease. Sarah, her sister, and her sister’s husband moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1878, to escape plague. Sarah worked as a maid.

When she was fourteen, Sarah married Moses McWilliams, mainly to escape the abuse inflicted by her sister’s husband. On June 6, 1885, she bore a daughter, Leila. When her husband died two years later, Sarah and Lelia moved to St. Louis, Missouri. Sarah married John Davis on August 11, 1894. That marriage ended in 1903.

Annie Turnbo Malone, an African American hair care entrepreneur based in St. Louis, had developed and manufactured her own line of hair care products for African American women. During the height of the Jim Crow segregation, Malone was able to establish a prosperous hair care business. Malone used her treatment to restore Breedlove’s hair loss.

Breedlove began to work with Malone in 1903. In 1905, Breedlove moved to Denver, Colorado, as an agent for Malone. In January 1906, Breedlove married a newspaper sales agent, Charles Joseph Walker. After changing her name to Madam C. J. Walker, she established her own business and sold her own hair care product, Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower.

Before the introduction of the straitening comb, African American women pressed and straitened their hair using a hot iron. Walker’s hair treatment changed that. It consisted of shampooing a person’s hair, applying a hair growing cream, and using heated iron combs to straighten the hair. When Malone learned about Walker’s fledgling enterprise, she accused Walker of copying Poro’s products. Walker denied the claims and struck out on her own.

In September 1906, Walker and her husband toured the United States, promoting their products and training sales agents. From 1908 to 1910, they operated a beauty training school, the Lelia College of Hair Culture, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The company’s mainly female agents became familiar figures in cities and towns throughout the United States and the Caribbean. Thousands of agents set up their own in-home shops, where they used and marketed Walker’s products.

The sales representatives made house calls wearing white shirtwaists and long, black skirts. They carried bags that contained hair care products. Madame Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower and a collection of other beauty products were stored in tin containers that were decorated with a portrait of Mae Walker Perry, the adopted daughter of Lelia Walker. Perry’s long, attractive hair was the perfect advertisement for Walker’s products. Walker advertised heavily in black newspapers and magazines. Her husband, who had been a newspaper salesman, provided advice about the company’s marketing and advertising efforts.

Every summer, several African American professional, fraternal, and social organizations held national conventions in cities throughout the United States. These were elaborate, weeklong events where hundreds of delegates and their families and guests would gather. Business meetings were held during the day, while dinners, dances, and other social events took place in the evening. Walker attended several of these gatherings. After making sure that the event was in full swing, she would make a conspicuous entrance in her chauffeur-driven limousine, elegantly dressed in the latest fashions. These displays of wealth and success served as means of promoting her business.

In 1910, Walker moved the company’s operations to Indianapolis. There she established Madam C. J. Walker Laboratories to manufacture cosmetics and train beauticians. These entrepreneurs operated independent salons in black communities throughout the United States, where they styled women’s hair and sold Walker’s products. Walker was one of the pioneers of direct sales marketing strategies and commission sales. She was an advocate of women’s economic independence and created opportunities for thousands of African American women who otherwise would have been cooks or domestics or held other low-level positions. Walker organized clubs and held annual conventions for her sales representatives.

Walker constructed a building complex that covered an entire city block in downtown Indianapolis. The complex became the national headquarters and manufacturing site for Walker’s products, employing 3,000 women. The complex also served as a community center that housed a ballroom, a theater, a hair salon, and corporate offices. The theater was a movie house and venue for jazz performances. The Walker complex was an important institution that contributed to the growth and development of Indianapolis’s African American community.

In 1912, at the peak of her company’s success, Walker wanted to address the delegates at the National Negro Business League convention in Chicago, Illinois. She arrived at the event in her chauffeured limousine. The league’s founder, Booker T. Washington, was, at that time, the most powerful black leader in the United States. During the first two days of the convention, he ignored Walker’s requests to address the delegates. On the final day of the conference, Walker stood and admonished Washington, asking him to acknowledge her as a successful, self-made entrepreneur. Walker described how she started out laboring in cotton fields in the South. She went from washing clothes to cooking in kitchens and moved on to establish a successful business manufacturing hair care products.

In 1913, Walker contributed $1,000 to assist in the financing of an African American Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) in Indianapolis. This was the largest contribution made by an African American donor. Washington accepted Walker’s invitation to be a guest in her home during the dedication of the YWCA. He was so impressed that he invited Walker to be a keynote speaker at National Negro Business League’s 1913 convention.

The Walkers divorced in 1912. The following year, Madame Walker traveled to Central America and the Caribbean to explore business opportunities, and expanded her company into Jamaica, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Panama. She met Mary McLeod Bethune, the founder of Bethune-Cookman College (now Bethune-Cookman University) in Daytona, Florida, in 1912, at the National Association of Colored Women’s annual conference. Walker led a fundraising campaign for the tiny school, starting with her own $5,000 donation. As a result of the campaign’s success, the school was able to expand. Walker also contributed thousands of dollars to the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Alabama. She lobbied for antilynching laws and contributed $5,000, the largest donation ever, to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s Antilynching Fund. She also donated $25,000 to other African American organizations.

Walker moved into an elegant townhouse in the Harlem section of New York City in 1916. On August 31, 1917, she convened the first national convention of “beauty culturists” at Philadelphia’s Union Baptist Church. More than 200 women from throughout the United States attended the event, where they discussed sales, marketing, and management. By 1919, Walker employed 3,000 people at the Indianapolis facility factory and had more than 20,000 sales representatives.

The construction of Walker’s opulent home, Villa Lewaro, in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, was completed in August 1918. Walker died at Villa Lewaro on May 25, 1919, at the age of fifty-one. Walker’s daughter succeeded her as president of the Madame C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. Lelia, who by then had changed her name to A’Leila, went on to become an important presence in the Harlem Renaissance. In 1927, she converted a floor of her Harlem townhouse into a salon she dubbed the “Dark Tower.” It was a place where many of the writers and artists associated with the Harlem Renaissance regularly gathered.

Madam Walker left a legacy that went beyond the beneficiaries named in her will. Beauty salons became important institutions in African American communities. They allowed African American women to develop organizational, leadership, and entrepreneurial skills. The establishments provided a valuable alternative to the menial positions that were otherwise available. Salon owners maintained a level of autonomy that was unavailable to most other African Americans. Madam Walker was a pioneer who led the way for others to follow.—Leland Ware

WALKER, MARGARET [MARGARET WALKER ALEXANDER]

(July 7, 1915–November 30, 1998) Poet, novelist, essayist, biographer, scholar

Margaret Walker is widely recognized for her 1942 collection of poems For My People, and for her epic family history, Jubilee, published in 1966; however, her identity as a writer began during the period of the Harlem Renaissance.

Walker was born on July 7, 1915, in Birmingham, Alabama, to Marion Dozier Walker and Sigismond Walker. As the daughter of an educator and a minister, she grew up in an environment in which scholarship was encouraged. During the early 1930s, she enrolled in Dillard University in Louisiana. At Dillard, she met a number of Harlem Renaissance writers, including James Weldon Johnson, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Langston Hughes. Hughes was an encouraging and inspiring influence on her decision to write. After two years at Dillard, Walker transferred to Northwestern University in Chicago.

While in Chicago, she published her first poems in Crisis magazine. After graduating from Northwestern University, Walker became part of Chicago’s black literary community. From 1935 to 1939, she worked for the Works Progress Administration, initially as a social worker and then as a writer. During this period, she met Richard Wright and became involved in the South Side Writers’ Group. Her friendship with Wright encouraged her pursuit of writing and historical research. For Wright, she became a trustworthy friend and supportive colleague, often providing insight into historical and social research that would prove useful for Wright in his own writing. As the Harlem Renaissance came to a close, Walker made the decision to pursue an advanced degree from the University of Iowa.

In 1942, she completed a version of her collection of poems, For My People, which would serve as her master’s thesis at the University of Iowa. The publication of this collection brought Walker serious critical recognition as a poet. The collection, like the Harlem Renaissance, is a celebration of the culture and history of African Americans. The poetry reflects the resiliency, creativity, and intellect of an oppressed, yet courageous and determined, people. The title poem, “For My People,” is her most frequently anthologized work; this poem represents her as a writer. The poem and the collection are reflective of the folk cultural expression that is characteristic of her work.

Also during this period, she married Firnist James Alexander. After the publication of For My People, Walker began intense historical research and received a Rosenwald Fellowship. In 1949, she moved with her husband to Jackson, Mississippi, and taught at Jackson State College (now Jackson State University). She balanced mothering four children, teaching, and her historical research. Her research was rewarded with a Ford Fellowship in 1953.

In the 1960s, Walker returned to the University of Iowa in pursuit of her doctoral degree. In 1965, she earned her Ph.D. Her dissertation is a version of her family history, Jubilee; this work was the fruit of her historical research. Jubilee was published in 1966, and Walker was once again the focus of considerable critical attention. After completing her degree, she returned to Jackson and teaching.

During the 1970s, Walker published two collections of poetry: Prophets for a New Day in 1970 and October Journey in 1973. She also published essays, including A Poetic Equation, which consists of her conversations with poet Nikki Giovanni, in 1974, and How I Wrote Jubilee and Other Essays on Life and Literature in 1980. In 1988, she published one of the most critical and thorough biographies on Richard Wright, Daemonic Genius. The biography in some ways addresses the speculation about Walker’s relationship with Wright. The book suggests that she harbored remarkable disappointment in her relationship with the writer as a friend. In 1989, she published This Is My Century, a collection of new and old poems. This compilation maps the course of her literary career, indicating the influence of different periods and literary movements in the progress of her career as a writer. In 1997, Maryemma Graham edited a collection of essays by Walker entitled On Being Female, Black, and Free. The collection includes essays written during a six-year period that are both biographical and critical of social and political issues affecting African Americans.

Walker was diagnosed with breast cancer, which led to her death in 1998. She continues to be recognized as one of the inspiring voices of African American culture of the twentieth century.—Rebecca S. Dixon

WALLACE, BEULAH “SIPPIE”

(November 1, 1898–November 1, 1986) Blues singer

Beulah “Sippie” Wallace, known as the “Texas Nightingale,” was a blues singer who had excellent phrasing and rich vocal tones, talents that brought her in contact with such legends as Joe “King” Oliver, Louis Armstrong, and Clarence Williams. Her style of the Chicago shout and moan, with the southwestern honky-tonk, made her among the best blues singers of her time.

Born in Houston, Texas, on November 1, 1898, the fourth of thirteen children, Wallace’s involvement in music began at her father’s church, where, when old enough, she sang and played the organ. She was given the nickname “Sippie” because her teeth were far apart as a child, and she had the habit of sipping her food. As she got older, Wallace became enamored with the tent-show bands and traveling blues singers, and on several occasions she was allowed to dance in the chorus line. By the mid-1910s, she had begun traveling with a tent show that moved from Houston to Dallas, and she began to sing, act, and do solo ballads.

In 1912, Wallace moved with her younger brother, Hersal Thomas, to the Storyville District of New Orleans so they could work with their older brother, George W. Thomas, who was a pianist, songwriter, and publisher. While in New Orleans, Wallace married Frank Seales in 1914, and they divorced in 1917. She was married to Matt Wallace from 1917 to 1936. Wallace returned home to Houston in 1918, after the death of both parents, but she was still determined to have a career as a blues singer and entertainer. She started out as a maid and stage assistant to a snake dancer, sang with small bands and for other gatherings, and later sang with tent bands throughout Texas. It was during this time that she became known as the “Texas Nightingale.”

In 1923, Wallace moved to Chicago with her brother Hersal, and along with their brother George W., they formed a popular trio. Wallace’s first recordings, written in collaboration with George W., were “Shorty George,” which sold more than 100,000 copies, and “Underworld Blues,” both on the Okeh label. Between 1924 and 1927, Wallace recorded more than forty songs, for instance, “Lazy Man Blues” and “Special Delivery Blues,” and she worked with such greats as Louis Armstrong, Clarence Williams, and Johnny Dodds. With the deaths of Hersal in 1926 and George W. in the mid-1930s, Wallace lost family and partners. She moved to Detroit and became director of the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses in the late 1930s.

By the 1940s, Wallace was performing occasionally, but by the 1960s, she had become part of the revival of American folk music and the blues. She performed in Detroit and on tour, and was part of the American Folk-Blues Festival, which took her to Copenhagen, Sweden, in 1966. She introduced the song “Woman Be Wise, Don’t Advertise Yo Man,” which inspired singer Bonnie Raitt, and appealed to a strong female sensibility. Wallace performed at the Lincoln Center in 1977 and 1980, and recorded a new album, Sippie, in 1982, which includes seven new songs and was nominated for a Grammy. Wallace, known as the last of the blues shouters, was considered among the greats, alongside Bessie Smith, Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, and Alberta Hunter, and she was subsequently inducted into the Blues Foundation’s Blues Hall of Fame in 2003. She died in Detroit, Michigan, in 1986.—Lean’tin L. Bracks

WARD, AIDA

(February 11, 1903–June 23, 1984) Singer

From the 1920s until the late 1940s, Aida Ward was a popular songstress in the United States, Canada, and Europe. Ward was born in Washington, D.C., on February 11, 1903, and she graduated from M Street High School (later Dunbar High School). She appeared in amateur shows prior to moving to New York.

After performing at the Hollywood Club, Ward appeared in the musical The Frolics (1923). She was understudy for Florence Mills in Dixie to Broadway (1924–1925) in New York, as well as Blackbirds of 1926 in New York, London, and Paris. Ward then performed in the predominantly white musical The Manhatters (1927). After Mills’s death in 1927, Ward costarred in Blackbirds of 1928, with Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Adelaide Hall; the Broadway production featured Ward singing “I Can’t Give You Anything but Love.” In 1929, Ward recorded the song, and the Blackbirds cast performed at the Moulin Rouge in Paris.

Ward toured the United States and Canada, singing with Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway’s orchestras, on radio programs, and at the Apollo Theater, as well as the Cotton Club. In 1932, she sang “I’ve Got the World on a String” in the Cotton Club Parade revue. Two years later, she appeared at Broadway’s Beacon Theater with comedians George Burns, Gracie Allen, Jack Benny, and Milton Berle.

At least one of Ward’s several marriages ended in divorce. She retired as an entertainer in the late 1940s and operated a long-term care facility in Washington until 1969. Jerome Gist, Ward’s son from her first marriage, died in 1983. Ward died at Howard University Hospital.—Linda M. Carter

WARING, LAURA WHEELER

(May 16, 1887–February 3, 1948) Portrait artist, teacher

Laura Wheeler Waring

Laura Wheeler Waring is best known for her participation in the seminal Harmon Foundation exhibition in the 1920s and 1940s. The exhibition and the African American artists whose works were showcased contributed to the creativity that abounded during the Harlem Renaissance.

Waring was born on May 16, 1887, in Hartford, Connecticut, a world vastly different from the one in which the majority of African Americans lived. Most blacks lived in the South under a system of oppression and racism. Education was limited; opportunities were virtually nonexistent, and discriminatory laws and antiblack violence were pervasive. For blacks, life in the North was less harsh, less constricting.

Waring flourished in her hometown. Her father, Robert Foster Wheeler, was a pastor at Talcott Street Congregational Church, the first black church in the state. Her mother, Mary Freeman Wheeler, was a teacher and an artist. After Waring graduated from Hartford Public High in 1906, she followed in the footsteps of the five generations of her family and attended college. At the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, she studied with painters Thomas Anschutz and William Merritt Chase. Among her peers were painter Lenwood Morris and sculptor Mae Howard Jackson. Upon graduation in 1914, Waring received a scholarship to travel in Europe.

Waring’s experiences in Europe during this time and in subsequent visits sharpened her artistic skills and broadened her worldview. Her European trips also connected her to some of the leading African American artists, writers, and intellectuals of her day. While abroad, Waring studied at the prestigious Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris. For many African American artists and intellectuals, France was a popular destination, providing a reprieve from the confining racial oppressions of the United States and an environment in which they could nurture their artistic, literary, and intellectual development.

Upon her return to the United States after her first trip to Europe, Waring settled into a successful career. Her career, like her childhood and educational experiences, went against the times. Women were expected to marry, bare children, and settle into their roles as wives and mothers. Waring would marry; however, she pursued a career first, becoming a teacher at Pennsylvania’s State Normal School. While there, she married Walter E. Waring, a professor at Lincoln University. She went on to accept the position of director of the art department at Cheyney Training School for Teachers (now Cheyney University of Pennsylvania) in 1925.

As Waring’s life flourished, so did black life in Harlem, New York. In the 1920s, Harlem throbbed with the excitement and energy of African Americans eager to express their talents, deep love and pride for their culture, and shrewd understanding of the turbulent racial times in which they lived. In 1922, William E. Harmon, a white real estate developer, founded the Harmon Foundation in New York City. The foundation was established to pay tribute to African American artists. In 1928, the foundation hosted the first exhibit of African American artists in history. Waring’s refined portraits were included and reflected the pride, accomplishments, and elegance of a people who had transcended a turbulent past and present. In 1944, eight of Waring’s portraits were included in the foundation’s Portraits of Outstanding Americans of Negro Origin. Her portraits include important African American figures, many of whom played crucial roles during the Harlem Renaissance. Some of her subjects include Jessie Redmon Fauset, a Harlem Renaissance writer; W. E. B. Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson, who heavily supported the Harlem Renaissance movement; and famed opera singer Marian Anderson.

Waring’s work, however, did not end with the Harmon Foundation’s exhibits. Her work also frequently appeared in Crisis, the publication of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. (Waring was also a member of this organization.) Her work was exhibited at the Galerie du Luxembourg in Paris; at Howard University in Washington, D.C.; at the Brooklyn Museum in New York; at the Newark Museum in New Jersey; and in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

In addition to the exposure she received for her art, Waring received some public tributes following her death in 1948. In 1956, the Laura Wheeler Waring School in Pennsylvania was named in her honor. Her home in Philadelphia was also honored with a historical marker, a visible reminder of the life of a remarkable artist.—Gladys L. Knight

WASHINGTON, FREDERICKA “FREDI” CAROLYN

(December 23, 1903–June 28, 1994) Actress, activist

During the 1930s and 1940s, Fredericka “Fredi” Carolyn Washington was one of the first African American women to garner critical acclaim on the Broadway stage and in film as a dramatic actress. She was initially noticed by many because of her beauty and sophistication, yet her legacy extends beyond her early days as an ingenue on Broadway. In addition to her considerable talents as an actress, she is remembered as an activist who obdurately worked to improve Broadway and Hollywood’s treatment of subsequent generations of African American actors and actresses.

Washington was born in Savannah, Georgia, on December 23, 1903; she was the second eldest of Robert T. and Harriet Washington’s five children. After her mother’s death, Fredi and her younger sister Isabel attended Saint Elizabeth’s Convent in Cornwell Heights, Pennsylvania, until they were teenagers. Fredi then moved to Harlem; lived with relatives; and continued her education at the Julia Richman High School, the Egri School of Dramatic Writing, and the Christophe School of Languages. She was employed as a bookkeeper at Harry Pace’s Black Swan Record Company, where her father worked, until she auditioned for choreographer Elida Webb and was hired for the chorus in Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake’s Shuffle Along in the early 1920s; Josephine Baker was also a dancer in the Broadway musical, and the two young women became friends. In 1933, Washington married Lawrence Brown, a trombonist in Duke Ellington’s orchestra, and the couple divorced in 1951. When Washington married Hugh Anthony Bell, a dentist, in 1952, she moved to Stamford, Connecticut, and retired from show business.

Decades earlier, Washington had debuted as a dramatic actress in the 1926 Broadway play Black Boy, which starred Paul Robeson as a prizefighter. Washington was cast as Irene, a beautiful African American woman who passes for white. In 1927 and 1928, she performed in New York and Europe with Charles Moore as the ballroom dancers Moiret and Freddie. In London, Washington taught the Prince of Wales the black bottom, a popular 1920s dance. In 1931, Washington and her sister starred in Singin’ the Blues, the Broadway melodrama about Harlem life. (Isabel followed in her sister’s footsteps as a dancer and actress until she married Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Jr., an assistant minister at his father’s church, Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, and ended her career.) Fredi continued to appear in plays in the 1930s and 1940s. These included Sweet Chariot; Run, Little Chillun, an African American version of Lysistrata; A Long Way from Home; How Long Till Summer; and Mamba’s Daughters. The latter production starred Ethel Waters as Hagar, the mother of Washington’s character, Lissa.

Washington’s cinematic credits include the short films Black and Tan (with Duke Ellington,1929), Mills Blue Rhythm Band (1933), and Cab Calloway’s Hi-De-Ho (1934), as well as the full-length films The Emperor Jones (1933), Drums of the Jungle (1936), and One Mile from Heaven (1937), which also features Eddie “Rochester” Anderson and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. In The Emperor Jones, Washington once again plays Robeson’s romantic interest. Censors, fearful that audiences would assume that the film was depicting an interracial relationship, demanded that Washington’s light skin be purposefully camouflaged with darker cosmetics to make the love scenes more tolerable to audiences. Washington’s signature role, on the stage or screen, was as Peola Johnson in the 1934 film adaptation of Fannie Hurst’s novel Imitation of Life. Light-skinned Peola disowns her darker-skinned mother, played by Louise Beavers, and renounces their African American identity, as she passes for white with tragic consequences. Ironically, when the hit movie was remade in 1959, Peola was portrayed by a white actress.

Washington’s efforts to sustain an acting career were stymied by the limited number of stage and film roles available for African American women and by individuals on Broadway and in Hollywood who would not cast a black woman who looked white. Frustrated by the lack of acting opportunities, she became a founding member of the Negro Actors’ Guild (NAG), located in New York, in 1937. Other founding members included W. C. Handy, Paul Robeson, and Ethel Waters. Noble Sissle was the organization’s first president, and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson was honorary president. Washington served as NAG’s first executive secretary. The founding members sought to increase African American participation in stage productions, as well as in films; eradicate stereotypical characters and scenes; and press for more realistic images of black life. Washington was also involved with the Committee for the Negro in the Arts, the Cultural Division of the National Negro Congress, and the Joint Actors Equity-Theatre League Committee on Hotel Accommodations for Negro Actors. Her efforts as an activist extended beyond the entertainment industry. For example, she participated in boycotts spearheaded by Adam Clayton Powell Jr. demanding that Harlem businesses hire African Americans.

In addition, Washington found time for other endeavors. She was a casting consultant for various films and plays, including the Broadway productions Carmen Jones (1943) and Porgy and Bess (1943). Also in the 1940s, she was the theater editor and columnist for Adam Clayton Powell Jr.’s weekly newspaper the People’s Voice; she wrote “Headlines and Footlights” and a second column, “Fredi Speaks.” In the 1950s, Washington acted in radio episodes of The Goldbergs, a situation comedy about Jewish life. She was also the registrar for the Howard da Silva School for Acting.

Washington was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame in 1975. She received the CIRCA Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Performing Arts in 1979. She died in St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Stamford, Connecticut, in 1994. Washington was ninety years old and preceded in death by her second husband, who died in 1970. The Papers of Fredi Washington, 1925 to 1975, are housed at the Amistad Research Center at Tulane University.—Linda M. Carter

WASHINGTON, ISABEL [MARION MARIE THEODORE ROSEMARIE]

(May 23, 1908–May 1, 2007) Entertainer

Isabel Washington was an attractive, fair-skinned, redheaded actress, singer, and performer in the 1920s who enjoyed many starring roles onstage and in films. She was further inspired by the success of her older sister Fredi Washington, star of the acclaimed film Imitation of Life (1934). In spite of her success as an entertainer, Washington chose to shorten her career and became the wife of preacher and civil rights activist Adam Clayton Powell Jr.

Born Marion Marie Theodore Rosemarie on May 23, 1908, in Savannah, Georgia, Isabel’s mother died when she was young, and both she and her older sister Fredi attended Saint Elizabeth’s Convent in Cornwell Heights, Pennsylvania, before the family moved to Harlem, where Isabel’s maternal grandmother lived. In Harlem, Washington worked after school at Harry Pace’s Black Swan Record Company, the place where her father, Robert T. Washington, worked. Fletcher Henderson, a premier band leader of the 1920s and house pianist for the company, liked Washington’s voice, and in March 1923, at the age of fifteen, Washington made her first recordings.

In 1929, after frequenting theaters where her sister Fredi was rehearsing or working, Washington made her way into show business. She spent time as a chorus girl and worked in the well-known night spots the Cotton Club and Connie’s Inn. Washington’s performances earned her starring roles in the production Harlem (1929), written by Wallace Thurman; Bombolla (1929), and Singin’ the Blues (1931). She also had a key role in the only film blues singer Bessie Smith ever acted in, Saint Louis Blues (1929), an important movie documenting the Harlem Renaissance. Washington’s performances were reviewed as vivacious, radiant, and ebullient.

Washington decided to give up her career in 1933, after deciding to marry Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Jr., pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. Although Powell’s father was not supportive of his son marrying a divorced showgirl who had a two-year-old son, Preston, from a previous marriage to Preston Webster, a noted photographer in Washington, D.C., Powell used his determination and charm to gain acceptance for his fiancé, later known as “Belle.” The marriage, which lasted for twelve years, was the first of three marriages for Powell. After her divorce, Washington began teaching developmentally challenged children and devoted herself to community activities and causes.—Lean’tin L. Bracks

WASHINGTON, MARGARET “MAGGIE” MURRAY JONES

(March 9, 1861–June 4, 1925) Educator, clubwoman

Margaret Murray Washington

The years leading up to the Harlem Renaissance, and for a number of years into that time of black cultural reawakening, Margaret Murray Jones Washington worked to improve the lives of people, particularly women, in Alabama. Her work with the black women’s club movement in Alabama and throughout the United States was also notable. As leader and holder of other offices within the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, she helped black women address such issues as health, education, and care of family.

Washington was born in Macon, Mississippi, on March 9, 1861, the daughter of a washerwoman named Lucy and Irish immigrant James Murray. For reasons not specified, her white Quaker brother and sister took her in when she was seven years old. When only fourteen years of age, she taught school for a time and then entered Fisk University in 1881, as a part-time student. Washington worked to sustain herself while at Fisk. Maggie, as she was known by some, engaged in several cultural activities at Fisk. She was associate editor of the students’ literary magazine the Fisk Herald, president of a literary society, and a member of the debate team. Among her contemporaries at Fisk were W. E. B. Du Bois and Sterling Brown, father of a well-known son by that name.

In June 1889, educator and founder of Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) Booker T. Washington had dinner with the senior students and also gave the commencement address. Following graduation, Washington hired Maggie to teach English, and the next year she became lady principal and director of the Department of Domestic Service, later to become the Department of Girls’ Industries. In October 1892, Maggie became Washington’s third wife. She was a member of a fifteen-person executive committee that ran the school during Washington’s absence, and she also handled other duties traditionally assigned to a college president’s wife. Maggie and twelve other women formed the Tuskegee Women’s Club in 1895, and they opened a school near the college, on the Elizabeth Russell Plantation, to train young people and teach wives and mothers the basics of housekeeping, child care, and sewing. Maggie also began a reading club for black men. The clubwomen established Mother’s Meetings for blacks in Macon County. When Booker T. Washington addressed ministers and civic leaders at meetings on campus or in the community, he did so in the mornings, followed by Maggie’s address to women in the afternoon. The club began a Town Night School in 1910, and offered such technical courses as carpentry, bricklaying, cooking, and sewing to men and women.

The black women’s club movement began to reach new heights around this time. Washington organized the Alabama Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs in 1899. Joined by local educator and club member Cornelia Bowen, the group undertook a number of much-needed community activities. The women built a nursing home for the elderly and indigent, established a center for troubled youth, and built libraries. Washington’s work with the club movement was seen before then, in 1895, when the National Federation of Afro-American Women was organized, and she became its founding president. The next year, the organization merged with the Colored Women’s League, headed by community activist and educator Mary Church Terrell, and formed the National Association of Colored Women. When the new group met in Nashville, Tennessee, for its first convention, Washington was elected secretary of the executive board. After holding several positions within the organization, in 1914 she was elected president.

From 1919 until her death, Washington was president of the Alabama Association of Women’s Clubs. During her administration, the Rescue Home for Girls was established in Mt. Meigs, Alabama. She worked cautiously but diligently with the white southern clubwomen’s Commission on Interracial Cooperation, founded in 1918, to improve educational opportunities for blacks. Her work with black clubwomen in the formation of the short-lived International Council of Women of the Darker Races in 1920 is notable. Washington was a primary mover in its formation and served as its founding president, working to build links between women of color worldwide.—Jessie Carney Smith

WATERS, ETHEL

(October 31, 1896?–September 1, 1977) Singer, actor

Ethel Waters was born to Louise Anderson, a twelve-year old who had been raped by John Waters, a white man. She lived to become one of the most influential blues and gospel singers in recording history. Waters was a central figure in the music recording history of the Harlem Renaissance. While many blues singers were born in the Southern United States and honed their craft on the Chitlin’ Circuit, Waters became a pioneer in urban blues, and she worked to erase the color barrier by bringing blues music to as wide an audience as possible.

Waters grew up near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and began her career as a singer when she was five years old, singing in church choirs. As a youngster, she was known as “Baby Star” before becoming known as “Sweet Mama Stringbean” while singing on the black vaudeville circuit. Some of her early influences were such white vaudeville singers as Nora Bayes and Fanny Price. Waters had become recognized as a talented blues singer by 1917, based on her singing in Baltimore, particularly the song “St. Louis Blues,” and her rise to stardom caused a conflict among some female blues vocalists, most notably Bessie Smith.

Because she was a northern blues singer, Waters had to earn the respect of classic southern blues singers like Smith, who forbade Waters from singing the blues when they shared the same venue at 91 Decatur Street in Atlanta, Georgia. Nonetheless, at the behest of the audience, Smith relented, and Waters sang “St. Louis Blues.” Following a 1918 car accident, Waters moved back to Philadelphia, where she washed dishes until 1919, when, at the nudging of supporters, she moved to New York City at what some call the start of the Harlem Renaissance. The Harlem Renaissance marked the flowering of African American arts, letters, and music, and Waters positioned herself to be part of that movement as she became one of the most popular vocalists of the 1920s.

When she arrived in New York City, Waters sang at the Lincoln Theater before accepting a job for two dollars a night singing at Edmund’s Cellar, but she would not remain at Edmund’s Cellar for long. By 1921, she was recording with Cardinal Records before switching to the black-owned Black Swan Records, making her one of the first black women to make a recording. Her recordings of “Down Home Blues” and “Oh Daddy” were the first blues recordings for the label.

Willing to make a strong run at living on the sound of her voice, Waters took to the road with Fletcher Henderson to promote her work on the black vaudeville circuit. In 1925, she signed with Columbia Records and began touring on the white vaudeville circuit to promote her new work. As a result of her talent and charisma, Waters broke the color barrier between the black and white vaudeville worlds. On October 20 of that year, her recording of “Dinah” became one of the most important recordings of her career. Not only was “Dinah” the best-selling song of her career, but Waters’s recordings with Columbia, along with marking the prelude to the scat singing of Louis Armstrong, helped bring black urban blues to a broader audience. By 1929, the performer was singing at clubs owned by Al Capone for more than $1,200 a week. In 1933, she recorded “Stormy Weather,” a work that would later be covered by Frank Sinatra and Billie Holiday.

While she was a talented singer, Waters also emerged as an actress beginning in 1927, with the musical Africana. She went on to play significant roles on Broadway and the silver screen of Hollywood, where, in 1949, she earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress in the landmark film Pinky. The following year, she received a New York Drama Critics Award for Best Actress, and during her time in film she worked with some of the great artists of her time, most notably Duke Ellington. Along with her voice, Waters was a master of the written word, and in 1951, she published her first autobiography, His Eye Is on the Sparrow.

The gospel hymn “His Eye Is on the Sparrow,” written during the first decade of the twentieth century, is closely associated with Waters, not only because of the title of her first autobiography, but also because she sang it so soulfully when she toured with evangelist Billy Graham from 1957 until 1976. Waters was a woman of good faith and good hope. In many ways, she could not have chosen a more fitting gospel. Based on the Gospel according to Matthew, the lyrics of “His Eye Is on the Sparrow” exude warmth and comfort, and her clean phrasing highlights her strong faith in a world of uncertainty. In 1977, Waters published To Me It’s Wonderful, her second autobiography. The book focuses on her life and work with Billy Graham, along with marking a return to the sacred music of her early life.

Waters died in Chatsworth, California, from heart disease in 1977, yet her vocal performances will be remembered for all time. For her lyricism, as well as her contribution to the vocal arts, she was, in 1998, posthumously awarded a Grammy Hall of Fame Award for her recording of “Dinah.” “Stormy Weather” won a Hall of Fame Award in 2003, in the genre of jazz, and “Am I Blue?” was given the same recognition in 2007.

Waters was a true renaissance woman. She moved easily from stage to screen, and the blues she sang in clubs early in her life became the gospels she sang for a nation in later life, making her one of the most versatile performers of the Harlem Renaissance. For Waters, music and human experience mattered more than the color of one’s skin. Whether it was through print, the screen, the stage, or music, she always bridged the gap between people with her special blend of artistic creativity, deep pathos, and respect for the human spirit.—Delano Greenidge-Copprue

WEBB, ELIDA

(August 9, 1895–May 1, 1975) Dancer, choreographer

Elida Webb began her career during the earlier years of the Harlem Renaissance and broke racial and gender barriers in the 1920s. One of Broadway’s first African American choreographers, as well as one of the first known African American female choreographers, she helped popularize the Charleston and worked with various entertainers, including Josephine Baker, Florence Mills, Fredi Washington, Lena Horne, and Ruby Keeler.

Webb was born in Alexandria, Virginia, on August 9, 1895. She received dance training from vaudeville singer and choreographer Ada Overton Walker. Webb was married to Garfield Dawson, who was also known as George “The Strutter” Dawson Jr.

Webb was a chorus girl in Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle’s Shuffle Along, an all-black musical that was staged on Broadway in 1921 and 1922. During the next two years, she choreographed and performed in Runnin’ Wild, a Broadway musical that featured her rendition of the Charleston. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Webb appeared in four additional Broadway productions: Lucky, Singin’ the Blues, Show Boat, and Flying Colors. From 1923 to 1934, she was a dancer and choreographer at Harlem’s Cotton Club, which featured orchestras led by Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway, as well as such singers as Ethel Waters and Adelaide Hall. The talented and creative performer was also a choreographer for the Zeigfield Follies, Apollo Theater, and Lafayette Theater.

Waters died in New York City in 1975. In The Cotton Club, the 1984 film starring Richard Gere and Gregory Hines, Norma Jean Darden portrays Webb.—Linda M. Carter

WELCH, ELISABETH

(February 19, 1904–July 15, 2003) Singer

Elisabeth Welch

Elisabeth Welch is best known as a successful singer and actress who performed in many of the major all-black musical revues in the 1920s, at the height of the Harlem Renaissance. She performed with such artists as Josephine Baker, Adelaide Hall, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and Ethel Waters. The singer spent most of her career after the 1930s performing in Europe, while periodically returning to the United States.

Welch was born on February 19, 1904, in the Manhattan, New York, area known as San Juan Hill. She was of mixed race. Her mother was of Scottish and Irish heritage, and her father of African American and Native American heritage. Her household operated on a strict Baptist perspective promoted by her father, who also worked as a gardener on an estate in Englewood, New Jersey. In spite of her strict upbringing, she made her first stage debut at eight years of age in the classic HMS Pinafore. After completing high school, Welch initially wanted to go into social work, but she was cast in the musical Liza in 1921, which began a long and successful career. It was during her performance in Liza that Welch introduced the Charleston, a dance craze of the Jazz Age, but it would be some time before the dance actually caught on. Because of her father’s strict Baptist beliefs, she felt that her decision to become part of the “low” life of show business was partly why her father left the family.

Welch starred in many early all-black Broadway shows, for instance, Runnin’ Wild (1923) and Chocolate Dandies (1924), which also featured Josephine Baker, and in 1928, she performed in the highly successful show Blackbirds. She was invited to perform in Paris in 1929, which included performances at the Moulin Rouge. Welch returned to New York City in 1930, to open a new nightclub and fill a singing role in Cole Porter’s The New Yorkers, which incorporated the controversial song “Love for Sale” (it was considered controversial because of its suggestive lyrics). After the show’s run from 1930 to 1931, the singer made her home in London and brought to Europe many showstopping performances. In 1934, Welch shared billing at the London Palladium with Cab Calloway and sang the song Shanty Town, written for Welch by Ivan Novello for his musical Glamorous Nights in 1935. In addition, Welch appeared in movies with such actors as Paul Robeson in the British films Show Boat, Song of Freedom, and Big Fella, and she performed as one of the first artists on television, all while having a regular spot on the radio series Soft Lights and Sweet Music. From the many songs she sang by George Gershwin, Jerome Kern, and Noel Coward, Welch chose “Stormy Weather,” written by Harold Arlen and Ted Koehler, as her signature song.

In the late 1930s, Welch continued to sing in various revues while in Europe and performed for the troops during World War II. Her career lasted for nearly thirty years in England, and in the 1980s she performed in New York City, reviving many of the songs she sang for greats the likes of Irving Berlin. She appeared in the show Black Broadway in 1980, and in 1986, she performed in the one-woman show Time to Start Living, which earned her an Obie Award. Welch died in Northwood, Middlesex, United Kingdom.—Lean’tin L. Bracks

WELLS-BARNETT, IDA B.

(July 16, 1862–March 25, 1931) Journalist, lecturer, social activist, clubwoman, feminist, antilynching crusader

Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Ida B. Wells-Barnett ascended to prominence between 1892 and the decade of the Roaring Twenties, which was an era of unparalleled flourishing of African American culture branded as the Harlem Renaissance or Negro Renaissance. Known for having an activist authority, the Harlem Renaissance era acted as both a commemoration and advancement of the intellectual acumen of American blacks. Expressed as a literary movement and social uprising against structural racism inculcated by the Jim Crow laws, diasporic individuals of African descent from throughout the United States and West Indies used the period to recast the identity of their brothers and sisters through the mediums of music, literature, and the visual and performing arts. This era of black expression also kindled the concept of the “New Negro Woman,” especially as it related to female poets, authors, and intellectuals. Wells-Barnett was among the women who used the movement to express their views on race and gender relations.

The oldest of eight children, Wells was born on July 16, 1862, in Holly Springs, Mississippi, to James Wells and Elizabeth Bell Wells. Born into slavery six months before President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation and reared during Reconstruction, she came of age during the post–Reconstruction period and spent her adult life fighting the racial inequities wrought by Jim Crow’s systemic structural impediments.

Although her parents were slaves, they transitioned from slavery to freedom during Wells’s formative years. Her father, a proficient carpenter, launched his own business in 1867, and her mother became noted for her gastronomic talent; however, a little more than a decade after her father established his business and the family seemed poised to become productive participants in the American experiment, they were beset by a dreaded disease that tore it asunder. The yellow fever epidemic of 1878, which was spread by a mosquito-borne viral infection, completely disrupted the lives of Wells and her family. Her father, mother, and nine-month-old brother Stanley succumbed to the epidemic, which swept through not only Mississippi, but raged from the port of New Orleans to Memphis, east to Alabama, and west to the Louisiana Valley.

After the death of her parents and youngest brother, Wells took on the responsibility of rearing her younger siblings. Having attended Shaw University, she taught for a while at a school six miles from her home for a monthly salary of twenty-five dollars. In 1880, she accepted an invitation from her aunt, Fanny Butler Wells, to move to Memphis, Tennessee. In Memphis, she accepted employment with the Shelby County school system as a teacher, a position in which she earned slightly more than she did in Mississippi.

Teaching in Woodstock, Tennessee, which was approximately twelve miles north of Memphis, required her to patronize the Chesapeake, Ohio, and Southwestern Railroad twice a day. Her travels to and from Woodstock catapulted Wells into a career of activism. Having purchased a first-class ticket, when she boarded the train, she took a seat in the “Ladies’ Car.” After the conductor forcibly removed her, she challenged racially segregated accommodations by filing suit against the railroad in 1884. Although the circuit ruled in her favor and awarded her $500 in damages, the Tennessee Supreme Court reversed the lower court’s decision in 1887.

Wells later taught in the Memphis school system, and during summer sessions she matriculated at Fisk University in Nashville. During her stay in Memphis, she became part of an intellectual and politically active African American community. She joined a lyceum, composed primarily of other teachers who enjoyed music, reading, debating political issues of the day, giving recitations, writing, and presenting essays. It was in Tennessee’s Bluff City that Wells launched her career as an activist and journalist. Her social and journalistic activities in Memphis would ultimately thrust her into the Harlem Renaissance.

Writing under the pen name Iola, Wells published accounts of her train experience in such African American newspapers as the New York Freeman and Detroit’s Plaindealer. At the National Press Association’s conference in Kentucky, she presented a paper, “Women in Journalism, or How I Would Edit.” She later became editor of the Evening Star. In 1889, the teacher-turned-journalist purchased one-third interest in Memphis’s Free Speech and Headlight, a militant journal owned by Reverend Taylor Nightingale, pastor of the Beale Street Baptist Church, and J. L. Fleming. Two years later, the “Princess of the Press,” as she was called, became a fulltime journalist and editor of the Free Speech after the school board fired her for writing a scathing editorial critical of Memphis’s substandard racially segregated schools, as well as its unequal distribution of resources allocated to African American schools.

In 1892, events in Memphis changed the course of Wells’s life. Law enforcement officials arrested a trio of African American grocers, Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart, all friends of the fearless journalist. Later, a mob dragged them from the jail and shot them to death in the infamous “Lynching at the Curve.” Outraged, Wells bought a pistol for protection, asserting, “One had better die fighting against injustice than to die like a dog or a rat in a trap.” In her editorials, the young journalist urged African Americans to leave Memphis. Outraged by this, the most heinous act of brutality perpetrated against African Americans since the Memphis Riots of 1866, where some forty-six African Americans and two whites died during the uprising, she urged African Americans to migrate from Memphis. The African American community listened to the clarion call and emboldened all who could to leave the Bluff City. In addition, there were calls for those staying behind to refrain from patronizing the City Railroad Company. Prodded by angry editorials in the Free Speech and calls of “On to Oklahoma,” 2,000 African Americans left Memphis and put the streetcar company in dire financial straits. Throughout the spring, Wells’s editorials “demanded that the murders of Moss, McDowell, and Stewart be brought to justice.” She exposed lynching as a stratagem to eliminate prosperous, politically active African Americans and condemned the “thread-bare lie” of rape used to justify violence against African Americans. Her indictments infuriated white Memphians, principally her intimation that southern white women were sexually attracted to black men. While Wells was in Philadelphia, a committee of “leading citizens” destroyed her newspaper office and warned her not to return to the city.

The “Lynching at the Curve” and her cogent and caustic pen denouncing the atrocity perpetrated by Memphis whites brought Wells national and international attention. Exiled from the South, she persevered in her struggle against racial injustice and the lynching of African Americans as a columnist for the New York Age, a newspaper owned and edited by T. Thomas Fortune and Jerome B. Patterson.

Wells moved to New York; bought an interest in the New York Age; and intensified her campaign against lynching through lectures, newspaper articles, and pamphlets. Works from this period include Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892); A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States, 1892, 1893, and 1894 (1895); and Mob Rule in New Orleans (1900). To make her antilynching crusade international, she lectured in Great Britain in 1893 and 1894, and wrote a column entitled “Ida B. Wells Abroad” for the Chicago Inter-Ocean. Wells also cowrote The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbia Exposition: The Afro-American’s Contribution to Columbia Literature, a pamphlet created to protest the exclusion of blacks from the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. In 1893, she moved to Chicago and worked for Chicago’s Conservator, the city’s first African American newspaper, founded and edited by Ferdinand L. Barnett.

On June 27, 1895, Wells married Barnett, a prominent Chicago attorney and widower with two small sons, and added his name to hers. They later became the parents of four children. She bought an interest in the Conservator and continued to write forceful articles and essays, including “Booker T. Washington and His Critics” and “How Enfranchisement Stops Lynching.” Her militant views, support of Black Nationalist Marcus A. Garvey, and direct criticism of such race leaders as Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois embroiled her in controversies and disagreements with leaders in the African American community. After she applauded the accomplishments of Garvey, the U.S. Secret Service classified Wells-Barnett as a radical.

After a brief retirement from public life following the birth of her second child, Wells-Barnett continued her campaign for racial justice, the political empowerment of blacks, and the enfranchisement of women. In 1898, she met with President William McKinley to protest the lynching of a postal worker and urge the passage of a federal law against lynching. After a burst of violence against African Americans in Springfield, Illinois, she signed the call for a conference, which led to the 1909 formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). She disassociated herself from the NAACP because of differences with Du Bois over strategy and racial politics. In 1910, Wells-Barnett founded the Negro Fellowship League (NFL) to provide housing, employment, and recreational facilities for southern black migrants. Unable to garner sufficient support for the NFL, she donated her salary as an adult probation officer following her appointment to the office in 1913.

An early champion of rights for women, Wells-Barnett was one of the founders of the National Association of Colored Women. In Chicago, she organized the Ida B. Wells Club; as its president, she established a kindergarten in the black community and successfully lobbied, with the help of Jane Addams, against segregated public schools. She also founded the Alpha Suffrage Club, which, in 1913, sent her as a delegate to the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s parade in Washington, D.C. Refusing to join black delegates, who were segregated from white suffragists at the back of the procession, she integrated the parade by marching with the Illinois delegation. Through her leadership, the Alpha Suffrage Club became actively involved in the 1928 congressional election of Oscar Stanton DePriest, the first African American alderman of Chicago and first African American congressperson elected from the North. Her interest in politics eventually led to Wells-Barnett’s unsuccessful campaign for the Illinois State Senate in 1930.

In 1918, in her unremitting crusade against racial violence, Wells-Barnett covered the race riot in East St. Louis, Illinois, and wrote a series of articles on the uprising for the Chicago Defender. Four years later, she returned to the South for the first time in thirty years to investigate the indictment for murder of twelve innocent farmers in Elaine, Arkansas. She raised money to publish and distribute 1,000 copies of The Arkansas Race Riot (1922), in which she recorded the results of her investigation.

Wells-Barnett continued to write throughout the final decade of her life. In 1928, she began an autobiography, which was published posthumously, and she recorded the details of her political campaign in a 1930 diary. She died in 1931, after a brief illness.

The women of the Harlem Renaissance were quite diverse. Some characterized themselves as active protesters and were ardent supporters of the struggle against the most vituperative practices of bigotry and racism, while others espoused a reflective position. Notwithstanding, the life of Wells-Barnett epitomizes a lifetime of endless struggle against the societal inhumanity perpetrated against African Americans and women.—Linda T. Wynn

WEST, DOROTHY

(June 2, 1907–August 16, 1988) Novelist, short story writer, journalist

Considered a minor figure in the Harlem Renaissance tradition, Dorothy West is primarily noted for her novels The Living Is Easy (1948) and The Wedding (1995), both influential works that attempt to illustrate the lives of the black bourgeoisie and the issues surrounding class in the upward movement of middle-class black Americans.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, on June 2, 1907, West was the only child of a former slave-turned-businessman and his wife—the first black family to later purchase property in Martha’s Vineyard as part of the small and developing black middle class. These experiences perhaps proved the most influential in shaping West’s aesthetic and literary approach, her novels foregrounding class as being more important in the United States than issues of color and race.

West’s literary career began in 1926, with the publication of her short story “The Typewriter” in Opportunity magazine. She later traveled with Langston Hughes and twenty black intellectuals to the Soviet Union to film Black and White—a propaganda film about the oppression of the black community. Although the film was never completed, West stayed in the Soviet Union for an additional nine months, only returning to the United States with the death of her father. With her return, West continued her literary pursuits, founding Challenge magazine in 1934, with the goal of revitalizing the spirit of the earlier Harlem Renaissance. During her time as editor, she published several notable black authors, from Zora Neale Hurston to Helene Johnson to Claude McKay, before the magazine collapsed due to financial constraints in 1937. West attempted to revive her endeavors with New Challenge, publishing works by Margaret Walker, Ralph Ellison, and Richard Wright; however, this magazine also failed following editorial and financial issues, rolling out just a single issue before its demise.

With the collapse of Challenge and later New Challenge magazine, West worked as a welfare investigator and for the Federal Writers’ Project until the 1940s, when she began working for the New York Daily News, publishing short stories monthly until the 1960s. In 1947, she moved from New York to her cottage in Martha’s Vineyard, where she lived out the rest of her literary career. Shortly thereafter, in 1948, she published The Living Is Easy, her semiautobiographical novel. The novel examines the intraracial colorism present in the United States—a thematic approach seldom illustrated in the black fiction of her time, except for such texts as Jessie Redmon Fauset’s Colored American Style. During this time, West also wrote a column for the Vineyard Gazette, never abandoning her journalistic roots, and she eventually wrote her own column on Oak Bluffs from 1973 to 1983.

West’s longest and most renowned work is The Wedding, which she abandoned in the 1960s due to overwhelming fears that the novel would not be favorably received by the rising Black Panthers and other militant organizations that perceived black people as victims, thus denying the black bourgeoisie. The novel remained unfinished until its publication in 1995, after Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis had encouraged the completion of the project. The book, which illustrates the struggle of interracial relationships to succeed in a racist and classist American society, is arguably the biggest legacy that West has left behind as a notable woman of the Harlem Renaissance tradition. Also published in 1995 was The Richer, the Poorer, a collection of thirty short stories and essays that West produced throughout her literary career. Although she never reached fame or recognition until the end of her life, West is truly an underappreciated talent from her time.—Christopher Allen Varlack

WHITMAN SISTERS: MABEL [MAY], ESSIE, ALBERTA [BERT], ALICE

(1880–1962), (1882–1963), (1887–1964), (1900–1969) Vaudevillians, dancers, singers, businesswomen

The Whitman Sisters

Mabel, Essie, Alberta, and Alice Whitman were the daughters of Albery Allison Whitman (bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, a dean of Morris Brown College, and a noted poet) and Caddie Whitman (who served as their chaperone until her death). Their father taught them to dance as children. They sang and danced in church and on tours, and their brother Caswell performed with them during their youth. He, too, later became a noted musician.

From the late 1800s to the 1930s, the Whitman Sisters had one of the most popular acts in black vaudeville; they were credited with having the biggest, flashiest, fastest, classiest, and most dignified shows, with no bawdy material. The company had between twenty and thirty performers, including dancers, comedians, female singers, a chorus line of twelve women, and a five- or six-piece jazz band led by Lonnie Johnson for nine years. They were credited with providing opportunities and inspiration for numerous performers, most notably Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Ethel Waters, and Count Basie.

The sisters began their professional career early; their fair skin was an advantage to their acceptance, for they consistently played before white audiences and often with white groups. In 1899, they began their professional career, touring Missouri, Florida, and later the white vaudeville circuit. Alberta joined Essie and Mabel on a European tour, and in 1902, they toured at the Grand Opera House in Atlanta, Georgia. In 1904, the sisters formed the Whitman Sisters’ New Orleans Troubadours; each sister had a distinct role. Mabel, the eldest, was the producer, director, and manager; Alberta was considered one of the best male impersonators; Essie was a comedienne and singer (contralto) who worked on costumes and design for the shows; and Alice, who joined in 1909, after their mother’s death, was billed as the “Queen of Taps” and a “champion cakewalk dancer” known for such dances as the Shim Sham Shimmy and Ballin’ the Jack (she was succeeded by her son Albert, also known as “Little Pops”). Mabel was married to “Uncle” Dave Payton, who tutored the children. Cast members were held to high moral and artistic standards. Their operating base moved from Atlanta to Chicago in 1905.

In 1910, the group became known as the Whitman Sisters’ Own Company. Mabel later formed Mabel Whitman and the Dixie Boys, an act that toured Germany and Australia, with her singing and the children dancing. The sisters continued to form road-show companies. Mabel’s entrepreneurial talents were evident; she was in charge of the business—organization and bookings—and other members of the family controlled additional aspects of the show. They later toured with the Theater Owners’ Booking Association, a black vaudeville traveling circuit, with top billing.

With the death of Mabel in 1943, from pneumonia, the company collapsed. The group’s religious and racial grounding are evident in that they provided moral and principled entertainment and a home for traveling African Americans in a racist society. The sisters were integrated and played to an integrated audience, helped further the careers of several performers, and provided racial uplift for countless individuals. Essie founded the Theatrical Cheer Club for performers during the Great Depression. Known as the “royalty of Negro vaudeville,” the Whitman Sisters, who had a sense of self and racial pride, presented a broad array of characters and styles, represented high-quality entertainment between 1900 and 1943, and had control of their company. Yet, they have almost been forgotten.—Helen R. Houston

WIGGINS, BERNICE LOVE

(March 4, 1897–?) Poet

Bernice Love Wiggins left El Paso, Texas, for California in the early 1930s and was never heard from again. The mystery surrounding her life and death make her one of the most enigmatic writers during the waning years of the Harlem Renaissance. Before she left El Paso, Wiggins experienced limited recognition for a brief period of writing. She published poems in the El Paso Herald, Chicago Defender, and Houston Informer, as well as in Half Center Magazine. She only produced one book of poems, Tuneful Tales (1925), which she self-published, but the poems illustrate an ability to find meaning and convey the complexity of both the black experience and black life on the Mexican border.

Wiggins was born on March 4, 1897, in Austin, Texas, to J. Austin Love. There are no records of her mother, and her identity was never found. Little is known about Wiggins’s early childhood, but in 1903, she moved to El Paso with her aunt; it was there that she was given the surname Wiggins. Her first-grade teacher noticed her talent and encouraged her to express herself in rhyme and verse.