1

FOCUSING AND TUNNELING

HOBBES: Do you have an idea for your story yet?

CALVIN: You can’t just turn on creativity like a faucet. You have to be in the right mood.

HOBBES: What mood would that be?

CALVIN: Last-minute panic.

—CALVIN AND HOBBES BY BILL WATTERSON

One evening not long ago we went to a vegetarian restaurant called Dirt Candy, its name coming from the owner-chef Amanda Cohen’s belief that vegetables are “candy” from the earth. The restaurant was known for a particular dish—the crispy tofu with broccoli served with an orange sauce—that all the reviewers raved about. They were right to rave. It was delicious, the table favorite.

Our visit was well timed. We learned the next day that Amanda Cohen was to appear on Iron Chef, a popular TV show in which chefs compete by preparing a three-course meal under great time pressure. At the beginning of the show, they learn the surprise ingredient that must be used in every course and have a few hours to design and cook the dishes. The show is extremely popular with aspiring cooks, food connoisseurs, and people who just like looking at food.

Watching the show, we thought Cohen had gotten fantastically lucky. Her surprise ingredient was broccoli, and she of course prepared her signature dish, the one we had just eaten, and the judges loved it. But Cohen did not get lucky in the way we thought. The surprise ingredient, the broccoli, did not allow her to showcase a dish already in her repertoire. Quite the opposite. Episodes are filmed a year in advance. Instead, as she puts it, “The Crispy Tofu that’s on the menu now was created for Iron Chef.” She created her signature dish that night. This kind of “luck,” if one can call it that, is even more remarkable. Here was an expert who had spent years perfecting her craft, yet one of her best dishes was created under intense pressure, in a couple of hours.

Of course, this dish was not created from scratch. Creative bursts like this build on months and years of prior experience and hard work. The time pressure focuses the mind, forcing us to condense previous efforts into immediate output. Imagine working on a presentation that you need to deliver at a meeting. In the days leading up to the meeting, you work hard but you vacillate. The ideas may be there, but tough choices need to be made on how to pull it all together. Once the deadline closes in, though, there is no more time for dawdling. Scarcity forces all the choices. Abstractions become concrete. Without the last push, you may be creative without producing a final product. Going into her appearance on Iron Chef, Cohen had several secret ingredients of her own, ideas she had been playing with for months or even years. Scarcity did not create them. Rather, it pushed her to bring them together into one terrific dish.

We often associate scarcity with its most dire consequences. This was how we had initially conceived of this book—the poor mired in debt; the busy perpetually behind on their work. Amanda Cohen’s experience illustrates another side of scarcity, a side that can easily go undetected: scarcity can make us more effective. We all have had experiences where we did remarkable things when we had less, when we felt constrained. Because she was keenly aware of the lack of time, Amanda Cohen focused on pulling everything from her bag of tricks into one great dish. In our theory, when scarcity captures the mind, it focuses our attention on using what we have most effectively. While this can have negative repercussions, it means scarcity also has benefits. This chapter starts by describing these benefits and then shows the price we pay for them, foreshadowing how scarcity eventually ends in failure.

GETTING THE MOST OUT OF WHAT YOU HAVE

Some of us hate meetings. Connie Gersick, a leading scholar of organizational behavior, has made a living out of studying them. She has conducted numerous detailed qualitative studies to understand how meetings unfold, and how the pattern of work and conversation changes over the course of a meeting. She has studied many kinds of meetings—meetings between students and meetings between managers, meetings intended to weigh options to produce a decision and meetings intended to brainstorm to produce something more tangible like a sales pitch. These meetings could not be more distinct. But in one way they are all the same. They all begin unfocused, the discussions abstract or tangential, the conversations meandering and often far off topic. Simple points are made in lengthy ways. Disagreements are aired but without resolution. Time is spent on irrelevant details.

But then, halfway through the meeting, things change. There is, as Gersick calls it, a midcourse correction. The group realizes that time is running out and becomes serious. As she puts it, “The midpoint of their task was the start of a ‘major jump in progress’ when the [group] became concerned about the deadline and their progress so far. [At this point] they settled into a … phase of working together [with] a sudden increase of energy to complete their task.” They hammer out their disagreements, concentrate on the essential details, and leave the rest aside. The second half of the meeting nearly always produces more tangible progress.

The midcourse correction illustrates a consequence of scarcity capturing the mind. Once the lack of time becomes apparent, we focus. This happens even when we are working alone. Picture yourself writing a book. Imagine that the chapter you are working on is due in several weeks. You sit down to write. After a few sentences, you remember an e-mail that needs attention. When you open your in-box, you see other e-mails that require a response. Before you know it, half an hour has passed and you’re still on e-mail. Knowing you need to write, you return to your few meager sentences. And then, while “writing,” you catch your mind wandering: How long have you been contemplating whether to have pizza for lunch, when your last cholesterol check was, and whether you updated your life insurance policy to your new address? How long have you been drifting from thought to vaguely related thought? Luckily, it is almost time for lunch and you decide to pack up a bit early. As you finish lunch with the friend you haven’t seen in a while, you linger over coffee—after all, you have a couple of weeks for that chapter. And so the day continues; you manage to get in a little bit of writing, but far less than you had hoped.

Now imagine the same situation a month later. The chapter is due in a couple of days, not in several weeks. This time when you sit down to write, you do so with a sense of urgency. When your colleague’s e-mail comes to mind, you press on rather than get distracted. And best of all, you may be so focused that the e-mail may not even register. Your mind does not wander to lunch, cholesterol checks, or life insurance policies. While at lunch with your friend (assuming you didn’t postpone it), you do not linger for coffee—the chapter and the deadline are right there with you at the restaurant. By day’s end this focus pays off: you manage to write a significant chunk of the chapter.

Psychologists have studied the benefits of deadlines in more controlled experiments. In one study, undergraduates were paid to proofread three essays and were given a long deadline: they had three weeks to complete the task. Their pay depended on how many errors they found and on finishing on time; they had to turn in all the essays by the third week. In a nice twist, the researchers created a second group with more scarcity—tighter deadlines. They had to turn in one proofread essay every week, for the same three weeks. The result? Just as in the thought experiment above, the group with tighter deadlines was more productive. They were late less often (although they had more deadlines to miss), they found more typos, and they earned more money.

Deadlines do not just increase productivity. Second-semester college seniors, for example, also face a deadline. They have limited time to enjoy the remaining days of college life. A study by the psychologist Jaime Kurtz looked at how seniors managed this deadline. She started the study six weeks from graduation. Six weeks is far enough away that the end of college may not yet have fully registered, yet it is short enough that it can be made to feel quite close. For half the students, Kurtz framed the deadline as imminent (only so many hours left) and for the others she framed it as far off (a portion of the year left). The change in perceived scarcity changed how students managed their time. When they felt they had little time left, they tried to get more out of every day. They spent more time engaging in activities, soaking in the last of their college years. They also reported being happier—presumably enjoying more of what college had to offer.

This impact of time scarcity has been observed in many disparate fields. In large-scale marketing experiments, some customers are mailed a coupon with an expiration date, while others are mailed a similar coupon that does not expire. Despite being valid for a longer period of time, the coupons with no expiration date are less likely to be used. Without the scarcity of time, the coupon does not draw focus and may even be forgotten. In another domain, organizational researchers find that salespeople work hardest in the last weeks (or days) of a sales cycle. In one study we ran, we found that data-entry workers worked harder as payday got closer.

The British journalist Max Hastings, in his book on Churchill, notes, “An Englishman’s mind works best when it is almost too late.” Everyone who has ever worked on a deadline may feel like an Englishman. Deadlines are effective precisely because they create scarcity and focus the mind. Just as hunger led food to be top of mind for the men in the World War II starvation study, a deadline leads the current task to be top of mind. Whether it is the few minutes left in a meeting or a few weeks left in college, the deadline looms large. We put more time into the task. Distractions are less tempting. You do not linger at lunch when the chapter is due soon, you do not waste time on tangents when the meeting is about to end, and you focus on getting the most out of college just before graduating. When time is short, you get more out of it, be it work or pleasure. We call this the focus dividend—the positive outcome of scarcity capturing the mind.

THE FOCUS DIVIDEND

Scarcity of any kind, not just time, should yield a focus dividend. We see this anecdotally. We are less liberal with the toothpaste as the tube starts to run empty. In a box of expensive chocolates, we savor (and hoard) the last ones. We run around on the last days of a vacation to see every sight. We write more carefully, and to our surprise often better, when we have a tight word limit.

Working with the psychologist Anuj Shah, we had an insight about how to take advantage of the breadth of these implications to test our theory. If our theory applies to all kinds of scarcity—not just money or time—it should also apply to scarcity produced artificially. Does scarcity created in the lab also produce a focus dividend? The lab allows us to study how people behave under conditions that are more controlled than the world typically allows, revealing mechanisms of thought and action. This follows a long tradition in psychological research of using the lab to study important social issues—conformity, obedience, strategic interaction, helping behavior, and even crime.

To do this, we created a video game based on Angry Birds for our research. In this variant, which we called Angry Blueberries, players shoot blueberries at waffles using a virtual slingshot, deciding how far back to pull the sling and at what angle. The blueberries fly across the screen, caroming off objects and “destroying” all the waffles they hit. It is a game of aim, precision, and physics. You must guess the trajectories and estimate how the blueberries will bounce.

In the study, subjects played twenty rounds, earning points that translated to prizes. In each new round they received another set of blueberries. They could shoot all the blueberries they had or they could bank some for use in future rounds. If they ended the twenty rounds with blueberries saved up, they could play more rounds and continue accumulating points as long as they had blueberries left. In this game, blueberries determined one’s wealth. More blueberries meant more shots, which meant more points and a better prize. The next step was to create blueberry scarcity. We made some subjects blueberry rich (they were given six blueberries per round) and others blueberry poor (given only three per round).

So how did they do? Of course, the rich scored more points because they had more blueberries to shoot with. But looked at another way, the poor did better: they were more accurate with their shots. This was not because of some magical improvement in visual acuity. The poor took more time on each shot. (There was no limit on how long they could take.) They aimed more carefully. They had fewer shots, so they were more judicious. The rich, on the other hand, just let the blueberries fly. It is not that the rich, simply because they had more rounds, got bored and decided to spend less time on the task. Nor is it that they became fatigued. Even on the first shots they were already less focused and less careful than the poor. This matches our prediction. Having fewer blueberries, the blueberry poor enjoyed a focus dividend.

In a way it is surprising that blueberry scarcity had effects similar to those observed with deadlines—time scarcity. Having few blueberries in a video game bears little resemblance to having only a few minutes left in a meeting or only a few hours to finish a project. Focusing on each shot, how far back to pull the sling, and when to release bears little resemblance to the complex choices that determine conversation and pace at work. We had stripped the world of all its complexity, all except for scarcity, and yet the same behavior emerged. These initial blueberry results illustrate how—whatever else may happen in the world—scarcity by itself can create a focus dividend.

The observed effects of scarcity in controlled conditions show one more thing. In the real world, the poor and the rich differ in so many ways. Their diverse backgrounds and experiences lead them to have different personalities, abilities, health, education, and preferences. Those who find themselves working at the last minute under deadline may simply be different people. When they are seen to behave differently, scarcity may be one reason, but any of several other differences may be playing a role as well. In Angry Blueberries, a coin flip determined who was “rich” (in blueberries) and who was “poor.” Now, if these individuals are seen to behave differently, it cannot be attributed to any systematic inherent personal differences; it must be due to the one thing that distinguishes between them: their blueberry scarcity. By creating scarcity in the lab in this way, we can untangle scarcity from the knots that usually surround it. We know that scarcity itself must be the reason.

The focus dividend—heightened productivity when facing a deadline or the accuracy advantage of the blueberry poor—comes from our core mechanism: scarcity captures the mind. The word capture here is essential: this happens unavoidably and beyond our control. Scarcity allows us to do something we could not do easily on our own.

Here, again, the game provides a suggestive glimpse. In theory, the rich in Angry Blueberries could have employed a strategy that simulated being poor. They could have used only three shots each round (like the poor) and saved the rest. This would have led them to play twice as many rounds as the “truly” poor and thus allowed them to earn twice as many points. In actuality, the blueberry rich did not earn anywhere near twice as much in the course of each game. Of course, the players may not have realized this strategy. But even if they had, they would not have been able to do much about it.

It is very hard to fake scarcity. The scarcity dividend happens because scarcity imposes itself on us, capturing our attention against all else. We saw that this happened in a way that is beyond conscious control—happening in milliseconds. It is why an impending deadline lets us avoid distractions and temptations so readily—it actively pushes them away. Just as we cannot effectively tickle ourselves, it is exceedingly difficult to fool ourselves into working harder by faking a deadline. An imaginary deadline will be just that: imagined. It will never capture our mind the way an actual deadline does.

These data show how scarcity captures attention at many time scales. We saw in the introduction that scarcity captures attention at the level of milliseconds—the time it took the hungry to recognize the word CAKE. We see it at the scale of minutes (aiming blueberries) and of days and weeks (college seniors getting the most out of their time before graduation). The pull of scarcity, which begins at milliseconds, cumulates into behaviors that stretch over much longer time scales. Altogether, this illustrates how scarcity captures the mind, both subconsciously and when we act more deliberately. As the psychologist Daniel Kahneman would say, scarcity captures the mind both when thinking fast and when thinking slow.

TUNNELING

At 10 p.m. on April 23, 2005, Brian Hunton of the Amarillo Fire Department received what was to be his last call.

Some calls turn out to be false alarms. Some—like this burning house on South Polk Street—turn out to be all too real. Not knowing which is which, firefighters take each one seriously. Each alarm creates a literal fire drill: firefighters must go from a relaxed evening at the firehouse to being at the fire scene, ready to face the flames. Not only must they get there quickly, but they must arrive in full gear and fully prepared. They rehearse and optimize each step. They even train getting dressed quickly. All this pays off. Within sixty seconds of the call, Hunton and the rest of the crew were fully loaded on the truck, their pants, jackets, hoods, gloves, helmets, and boots already on.

Those outside the firefighting community are surprised by how Hunton died. He did not die because of burns from the fire. Nor did he die from smoke inhalation or from building collapse. In fact, Hunton never made it to the fire. As the fire truck raced to South Polk Street, it took a sharp turn. As it turned the corner at full speed, the left rear door swung open. Hunton came tumbling out and his head struck the pavement. The massive force of the strike caused serious trauma to his head, from which he died two days later.

Hunton’s death is tragic because it could have been prevented. If he had been wearing a seat belt when the door accidentally swung open, he might have been rattled but he would have been safe.

Hunton’s death is particularly tragic because it is not unique. Some estimates place vehicle accidents as the second leading cause of firefighter deaths, after heart attacks. Between 1984 and 2000, motor vehicle collisions accounted for between 20 and 25 percent of firefighter fatalities. In 79 percent of these cases the firefighters were not wearing a seat belt. Though one cannot know for sure, it stands to reason that simply buckling up could have saved many of these lives.

Firefighters know these statistics. They learn them in safety classes. Hunton, for one, had graduated from a safety class the year before. “I don’t know of a firefighter who doesn’t wear his or her seat belt when driving a personal vehicle,” wrote Charlie Dickinson, the deputy administrator of the U.S. Fire Administration, in 2007. “I don’t know of a firefighter who doesn’t also insist family members buckle up as well. Why is it then that firefighters lose their lives being thrown from fire apparatus?”

Rushing to a call, firefighters confront time scarcity. Not only must they get on the truck and to the fire quickly, but a lot of preparation also needs to take place by the time they arrive at the fire. They strategize en route. They use an onboard computer display to study the structure and layout of the burning building. They decide on their entry and exit strategies. They calculate the amount of hose they will need. All this must be done in the brief time it takes to get to the fire. And firefighters are terrific at managing this scarcity. They get to distant fires in minutes. They reap a big focus dividend. But this dividend comes at a cost.

Focusing on one thing means neglecting other things. We’ve all had the experience of being so engrossed in a book or a TV show that we failed to register a question from a friend sitting next to us. The power of focus is also the power to shut things out. Instead of saying that scarcity “focuses,” we could just as easily say that scarcity causes us to tunnel: to focus single-mindedly on managing the scarcity at hand.

The term tunneling is meant to evoke tunnel vision, the narrowing of the visual field in which objects inside the tunnel come into sharper focus while rendering us blind to everything peripheral, outside the tunnel. In writing about photography, Susan Sontag famously remarked, “To photograph is to frame, and to frame is to exclude.” By tunneling, we mean the cognitive equivalent of this experience.

Firefighters, it turns out, do not merely focus on getting to the fire prepared and on time; they tunnel on it. Unrelated considerations—in this case the seat belt—get neglected. Of course, there is nothing unique to firefighters when it comes to tunneling, and there may be other reasons firefighters do not wear seat belts. But a seat belt that never crosses your mind cannot be buckled.

Focus is a positive: scarcity focuses us on what seems, at that moment, to matter most. Tunneling is not: scarcity leads us to tunnel and neglect other, possibly more important, things.

THE PROCESS OF NEGLECT

Tunneling changes the way we choose. Imagine that one morning you skip your regular gym session in order to get some work done. You are facing a tight deadline and that is your priority. How did this choice come about? It is possible that you made a reasoned trade-off. You calculated how often you’ve been to the gym recently. You weighed the benefits of one more visit against the immediate needs of your project and decided to skip. The few extra hours of work that morning were more important to you than exercise. In this scenario, if you were free of the mental influence of scarcity, you still would have agreed that skipping the gym that day was the best choice.

When we tunnel, in contrast, we choose differently. The deadline creates its own narrow focus. You wake up with your mind focused on—buzzing with—your most immediate needs. The gym may never even cross your mind, never enter your already full tunnel. You skip the gym without even considering it. And even if you do consider it, its costs and benefits are viewed differently. The tunnel magnifies the costs—less time for your project now—and minimizes the benefits—those distant long-term health benefits appear much less urgent. You skip the gym whether or not it is the right choice, whether or not a neutral cost-benefit calculation would have led you to the same conclusion. For the very same reason that we are more productive under the deadline—fewer distracting thoughts intrude—we also choose differently.

Tunneling operates by changing what comes to mind. To get a feel for this process, try this simple task: list as many white things as you can. Go ahead and give it a try. To make things easier, we will give you a couple of obvious ones to start you off. Take a minute and see what other white things you can name.

How many could you name? Was the task harder than you thought it would be?

Research shows that there is one way to make this task easier for you—and that is not to give you “milk” and “snow.” In experiments, people given these “helpers” name fewer total items, even counting the freebies.

This perverse outcome is a consequence of what psychologists call inhibition. Once the link between “white” and “milk” is activated in your mind, each time you think, “things that are white,” that activated link draws you right back to “milk” (and activates it further). As a consequence, all other things white are inhibited, made harder to reach. You draw a blank. Even thinking of examples for this paragraph proved hard. “Milk” is such a canonically white object that, once activated, it crowds out any others. This is a basic feature of the mind: focusing on one thing inhibits competing concepts. Inhibition is what happens when you are angry with someone, and it is harder to remember their good traits: the focus on the annoying traits inhibits positive memories.

The mind does not inhibit just words or memories. In one study, subjects were asked to write down a personal goal, an attribute that describes a trait (e.g., “popular” or “successful”) that they would like to attain. One half were asked to list a personally important goal. The other half were asked to list just any goal. Following this, as in the milk experiment above, both groups were asked to list as many goals (important or not) as they could. Starting off with an important goal led to 30 percent fewer goals being named. Just as “milk” tends to shut out other white objects, activating an important goal shuts off competing goals. Focusing on something that matters to you makes you less able to think about other things you care about. Psychologists call this goal inhibition.

Goal inhibition is the mechanism underlying tunneling. Scarcity creates a powerful goal—dealing with pressing needs—that inhibits other goals and considerations. The fireman has one goal: to get to the fire quickly. This goal inhibits other thoughts from intruding. This can be a good thing; his mind is free from thoughts about dinner or retirement savings, focusing instead on the upcoming fire. But it can also be bad. Things unrelated to the immediate goal (such as the seat belt) will not cross his mind; and even if they do, more urgent concerns drown them out. It is in this sense that the seat belt and the risk of an accident get neglected.

Inhibition is the reason for both the benefits of scarcity (the focus dividend) and the costs of scarcity. Inhibiting distractions allows you to focus. In our earlier example, why were we so productive working under a deadline? Because we were less distracted. The colleague’s e-mail does not come to mind, and if it does it is easily dismissed. And goal inhibition is why we were less distracted. The primary goal—to finish writing the chapter—captured our mind. It inhibited all those distractions that create procrastination, like e-mail, a video game, or a light snack. But it also inhibited things we ought to have attended to, such as the gym or an important phone call.

We focus and tunnel, attend and neglect for the same reason: things outside the tunnel get inhibited. When we work on a deadline, skipping the gym may or may not make sense. We just don’t think (or think enough) about it that way when we decide to forgo the gym for the deadline. Our mind is not on that subtle cost-benefit problem; it is on the deadline. Considerations that fall within the tunnel get careful scrutiny. Considerations that fall outside the tunnel are neglected, for better or worse. Think of an air traffic controller who manages several planes in the air. When a large passenger plane reports engine problems, she focuses on it. During that time, she neglects not only her lunch plans but also the other planes under her control, including ones that might suddenly find themselves on a collision course.

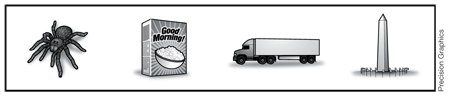

We saw the focus dividend in the Angry Blueberries experiment. And in the lab we can also see the negative consequences of tunneling. If scarcity-induced neglect is insensitive to the weighing of costs and benefits, we ought to see scarcity creating neglect even when it is detrimental to the person’s outcomes. To test for this, we ran another study with Anuj Shah, in which we gave participants simple memory tasks, each containing four items, such as this one:

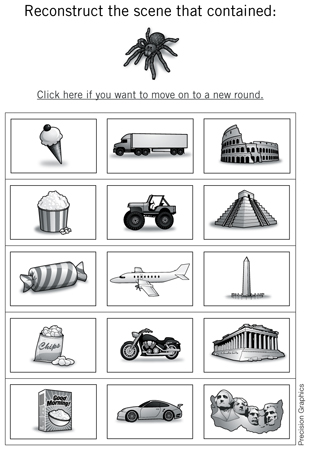

Subjects memorized these pictures and were later asked to reconstruct them. They were given one of the four items and asked to recall the other three. For example, after seeing the picture above, they might be asked:

Subjects had to retrieve from memory which of the other objects—a food, a vehicle, and a monument—went along with the spider in the original picture. They got points for correct responses, and they could take as long as they wanted. There was no time scarcity. But there was guess scarcity. They only had a fixed number of guesses they were allowed to make. As before, we created the guess poor and the guess rich.

To measure the cost of tunneling, we added a wrinkle. We had participants play two such games side by side. They were given two pictures to memorize and to reconstruct. And we made them poor (few guesses) in one game and rich (many guesses) in the other. So they experienced scarcity in trying to reconstruct one picture but not the other. Their total earnings depended on their performance on both games: they had to maximize total points earned. Think of it as having two projects, one with a deadline tomorrow and the other a week later. If people were to tunnel, then what they gain in one picture would be offset by worse performance on the other.

Consistent with the focus dividend, people were more effective guessers on the picture they were poor on. But they also tunneled: they neglected the other picture. And this was not efficient. They performed so much worse on the neglected picture that they earned, overall, fewer points than subjects who were poor on both pictures. They earned less even though they had more total guesses. A scarcity of guesses in both games meant they could not neglect either one, whereas abundance in one game led them to neglect that game in favor of the one they felt poor on. And they overfocused. Had the shift in focus to the poor game been deliberate, they would not have taken it to such an extreme. Clearly they did not gauge the costs and benefits of tunneling. They simply tunneled, and in this environment it hurt them.

We will call these negative consequences the tunneling tax. Naturally, whether this tax dominates the focus dividend is a matter of context and of payoffs. Change the game a bit and the dividend wins out. The point of the study was not to show that the costs of tunneling always dominate the benefits of focusing. Rather, what the study shows is that cost-benefit considerations do not determine whether we tunnel. Scarcity captures our minds automatically. And when it does, we do not make trade-offs using a careful cost-benefit calculus. We tunnel on managing scarcity both to our benefit and to our detriment.

THE TUNNELING TAX

I took a speed-reading course and read War and Peace in twenty minutes. It involved Russia.

—WOODY ALLEN

Since the examples above are abstract, we close with a few intuitive vignettes of how the tunneling tax can play out in daily life. These illustrate not necessarily how people might be mistaken but how tunneling can lead us to overlook certain considerations. First, some advice from the Wall Street Journal on how to save money.

OK. So you want to save an extra $10,000 by next Thanksgiving. How can you do it? You’ve heard the usual finger-wagging frugality lessons over and over. And you already do the obvious things, like cutting back on lattes, raising your insurance deductibles [emphasis added] and steering clear of expensive stores.

Is raising deductibles a good idea? For someone on a tight budget this is a hard question to answer. Yes, it saves money, but it comes at a cost. You may save money up front, but you run the risk of having to pay more of the cost in case of an accident. A reasoned choice about the deductible would trade off such considerations. But within the tunnel, one consideration looms large: the need to save money right now. Raising deductibles—like cutting back on lattes or on movies—saves money now and is firmly in the tunnel. The other concern—how to pay for repairs in case the car breaks down—falls outside the tunnel.

This can lead people not just to raise deductibles but to forgo insurance altogether. Researchers in poor countries have found it hard to get poor farmers to take up many kinds of insurance, from health insurance to crop insurance. Rainfall insurance, for example, would protect these farmers from the havoc that low (or very heavy) rainfall could do to their livelihood. Even with extremely large subsidies, most (in some cases more than 90 percent of farmers) do not insure. The same is true of health insurance. When asked why they are uninsured, the poor often explain they cannot afford insurance. This is ironic since you might think the exact opposite: that they cannot afford not to be insured. Here, insurance is a casualty of tunneling. To a farmer who is struggling to find enough money for food and vital expenses this week, the threat of low rainfall or medical expenses next season seems abstract. And it falls clearly outside the tunnel. Insurance does not deal with any of the needs—food, rent, school fees—that are pressing against the mind right now. Instead, it exacerbates them—one more strain on an already strained budget.

Another manifestation of tunneling is the decision to multitask. We may check e-mail while “listening in” on a conference call, or squeeze in a bit more e-mail on the cell phone over dinner. This has the benefit of saving time, but it comes at a cost: missing something on the call or at dinner or writing a sloppy e-mail. These costs are notorious when we drive. When you think about the multitasking driver, you think of the driver who is talking on a cell phone. Indeed, studies have shown that talking on a (non-handheld) cell phone while you drive can be worse than driving at above legal alcohol levels. But you might also want to think about that driver eating a sandwich. Studies show that eating while driving can be as big a danger. And it is a very common practice: one study found that 41 percent of Americans have eaten a full meal—breakfast, lunch, or dinner—while driving. Eating while driving saves you a bit of time, but you run the risk of staining your upholstery, having an accident, and increasing the chances of a different kind of spare tire: people consume more calories when they are distracted. Tunneling promotes multitasking because the time saving it allows is within the tunnel whereas the problems it creates often fall outside.

Sometimes when we tunnel, we neglect other things completely. When we are busy with a pressing project, we skimp on time with our family, put off getting our finances in order, or defer a regular medical checkup. When you are extremely rushed for time, it is easier to say, “I can spend time with the kids next week,” rather than, “Actually, the kids really need me. When exactly will I really have time next?” Things outside the tunnel are harder to see clearly, easier to undervalue, and more likely to get left out.

Companies are not immune to the psychology of scarcity. For example, during lean times, many firms slash their marketing budgets. Some experts believe that this is not a sound business decision. In fact, it looks a lot like tunneling. As one adviser for small businesses puts it:

In lean times, many small businesses make the mistake of cutting their marketing budget to the bone or even eliminating it entirely. But lean times are exactly the times your small business most needs marketing. Consumers are restless and looking to make changes in their buying decisions. You need to help them find your products and services and choose them rather than others by getting your name out there. So don’t quit marketing. In fact, if possible, step up your marketing efforts.

Settling this debate—whether cutting marketing expenses during recessions is efficient—would require a great deal of empirical work. What we can say is that the benefits of marketing look a lot like the kind of thing you would neglect in the tunnel, when you are focused on trimming your budget this quarter. Marketing—like the insurance policy—has a cost that falls inside the tunnel while its benefits fall outside.

In many of these examples, one can fairly question whether the choices made are bad. How do we know that the time saved eating while driving is not worth the increased accident risk? It is always a challenge to decide whether a particular choice was wrong. If by focusing on a deadline you neglect your kids, was that a bad choice? Who is to say? It depends on the consequences of performing poorly at work, the impact of your absence on your children, and even what you want out of life. An outside observer would need to struggle to untangle these considerations. But by exposing how tunneling operates, how some considerations are often ignored, the scarcity mind-set can shed light on the issue even without settling these debates.

It tells us, for example, that we should be cautious about inferring preferences from behavior. We might see the busy person neglect his children and conclude that he does not care as much about his kids as he does about his work. But that may be wrong, much as it would be wrong to conclude that the uninsured farmer does not particularly care about the loss of his crop to the rains. The busy person may be tunneling. He may value his time with his children greatly, but the project he is rushing to finish pushes all that outside the tunnel. He may look back later in life and report a great deal of anguish about not having spent more time with his children. This is genuine anguish and not merely compliance with a social norm. It is the predictable disappointment of anyone who tunnels. Projects must be finished now; the children will be there tomorrow. Looking back at how our time or money was spent during moments of scarcity, we are bound to be disappointed. Immediate scarcity looms large, and important things unrelated to it will be neglected. When we experience scarcity again and again, these omissions can add up. This should not be confused with a lack of interest; after all, the person himself regrets it.

We started this chapter by showing how scarcity captures our attention. We see now that this primitive mechanism compounds into something much larger. Scarcity alters how we look at things; it makes us choose differently. This creates benefits: we are more effective in the moment. But it also comes at a cost: our single-mindedness leads us to neglect things we actually value.