Chapter 14

Dive

Wading through the Shallows to Dive into Deep Creativity

“You don't get results by focusing on results. You get results by focusing on the actions that produce results.”

– Mike Hawkins

Okay, you've got your action plan worked out. Now it's time to apply your renewed ability to focus, your positive thinking and motivational visualization, and your passionate sense of purpose to creative productivity. That requires carving out time for deep dives into creative work. Instead of always treading water in a desperate effort to keep up with the relentless onslaught of distractions, you allow yourself to plunge into the projects that are the most important, and the most meaningful, to you.

For so many of us, when we do give ourselves time for creative work, we don't take the deep plunge. It's like we're snorkeling rather than scuba diving. We just don't think we can afford to take the time to really go deep. That's in part because we don't realize how productive we can be during creative work sessions if we are truly, utterly focused.

We tend to think that creative output requires a large time commitment. And we're concerned that if we fail to answer all, or at least most, of our emails, take phone calls when we get them, and process through all of the flotsam and jetsam of bureaucratic paperwork (so much of which is online now), we'll find ourselves drowning.

The truth is that most of us do have to keep up with a large volume of basic work tasks and we do have to be responsive to messages and calls. We have to get paperwork done on time and we can't just beg off on all, or even most, meetings. So in order to make time for deep creative work, we have to master the art of switching from the shallows to the depths. What's vital is to establish a basic pattern to your days for moving from deep concentration on creative projects, to attention to all of the routine demands you've got to keep up with.

To make time for deep creative work, we have to master the art of switching from the shallows to the depths.

Professor Cal Newport of Georgetown University has written several books on personal and professional performance, and he addressed the need to develop the ability to switch back and forth from the shallows to the depths in his 2016 book Deep Work. He has inspiring things to say about the payoffs of deep work, which he defines as, “the ability to focus without distraction on a cognitively demanding task. It's a skill that allows you to quickly master complicated information and produce better results in less time.”

“The ability to focus without distraction on a cognitively demanding task."

Newport is a computer scientist and he has studied the advance of the “second machine age” in which robots will be taking over so much work. He highlights that the ability to get into deep work mode is becoming ever-more important not only because of the epidemic of distraction but because the better we are at deep work, the more competitive advantage we will have in performing the jobs that even very smart machines won't be able to perform. He posits what he calls his Deep Work Hypothesis:1

The ability to perform deep work is becoming increasingly rare at exactly the same time it is becoming increasingly valuable in our economy. As a consequence, the few who cultivate this skill, and then make it the core of their working life, will thrive.

The heartening news he shares about this is that the ability to dive deep isn't something that's just bestowed by birth on some crème de la crème of the super-focused. It's a skill that we can all learn with practice.

©Paula May

Key to this is what Newport refers to as “alt tabbing” between shallow and deep work. How does he distinguish between them?

Deep Work = Professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skill, and are hard to replicate.

Shallow Work = Noncognitively demanding, logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted. These efforts tend not to create much new value in the world and are easy to replicate.

He outlines a number of basic approaches for toggling. They're not mutually exclusive, and I've been experimenting with all of them. You should, too, and you can adjust your approach as best fits your work situation over time.

The Monastic Philosophy: This approach is based on the practice of monks of retreating to isolation, renouncing worldly pursuits to devote all of their time to spiritual work.2 The idea is to protect yourself from all distraction by physically removing yourself to a quiet place and unplugging, for at least one or more days, to allow yourself the space and time to engage in uninterrupted work.

The Bimodal Philosophy: Here, you're balancing between monastic self-imposed exile and everyday social and professional engagement. You schedule a large block of time entirely away from the shallows of your everyday work every day, which is often best to do in the morning, and then attend to everything else for the remainder for the day.

The Rhythmic Philosophy: Here you're oscillating more frequently between deep and shallow work, so in shorter increments of time. A version of the Pomodoro technique would be a great way to create a rigorous pattern for this, perhaps dedicating several 90 minute blocks a day to deep work and coming up for check-ins with email and all in the time in between.

The Journalistic Philosophy: This is for when carving out substantial chunks of time in advance for deep work is simply not possible. We train ourselves to get into deep work mode quite quickly and take advantage of any opportunities as they come. It's named after a journalist's need to dig deep to focus and crank out a story on deadline in very little time and even with lots of noise going on all around them.

This one takes more practice. I've struggled with it but am beginning to find that I can get back into creative work more and more quickly and take good advantage of unexpected moments without demands on my time, such as when takeoff of a flight is delayed for 15 or 20 minutes. I can pull out my laptop and get right back into writing and get some significant work done that I've found I am happy with later.

Depending on the nature of your work, there are probably always going to be some days or weeks when you can't schedule much if any creative deep time. But this journalistic approach is not optimal, and you should strive not to let this become your default mode for deep work.

Ritualize the Dedication of Time and Space

It's said that greatness is founded on establishing a routine and the discipline to keep to it. As you work to establish your toggling system, be ruthless about time you have scheduled for your deep dives. Give that time up only for truly urgent demands.

Greatness is founded on establishing a routine and the discipline to keep to it.

This is hard. I know. I struggled mightily with it. It's such a fight not only because of intrusions, but because of what I call the cult of busyness. The work world has glorified being busy as a badge of honor, and we've learned to believe we have to show people we're really busy. If we're not emailing or on the phone or in a meeting, how can they see that we're busy?

©Lost Co

Busyness is distraction masquerading as productivity.

Busyness is distraction masquerading as productivity. If you make deep time and increase the quality of your output, trust me, no one will care how busy you look. Or, actually, they'll be amazed and impressed by what you've been able to produce even though you didn't seem to be crazy busy. There is no prize for answering x emails or attending y meetings every day. There's no reward for self-inflicted burnout.

A few key things made dedicating myself to scheduled deep work time much easier for me.

©Artiom Vallat

Establish a dedicated space. Find a place away from work and home that you can escape to. I tried locking myself in a conference room at my office and taking coffee/water/snack breaks or bathroom runs only when I knew there would be no one around for chitchat. That did help, but I found that the distractions of the office still invaded my mind. All of the sudden I'd find myself thinking about a client meeting or a report I had to get done instead of the project I had decided to focus on. My home office was worse. It's strewn with stacks of paperwork that always need filing, receipts to organize, bills to pay, and when my adorable daughters are home, I always want to go and play with them.

Establish a dedicated space. Find a place away from work and home that you can escape to. I tried locking myself in a conference room at my office and taking coffee/water/snack breaks or bathroom runs only when I knew there would be no one around for chitchat. That did help, but I found that the distractions of the office still invaded my mind. All of the sudden I'd find myself thinking about a client meeting or a report I had to get done instead of the project I had decided to focus on. My home office was worse. It's strewn with stacks of paperwork that always need filing, receipts to organize, bills to pay, and when my adorable daughters are home, I always want to go and play with them.

Some people find working at cafes does the trick. That wasn't possible for me. Their hubbub doesn't serve as focus-inducing white noise for me as I know it does for some people. I find myself listening to conversations, even if I put on headphones. Cafes are just filled with so many interesting people to ogle over!

Eventually, I began allocating regularly scheduled time to visit a small place in Lake Tahoe. I got the idea from the extraordinary creative producer J.K. Rowling, author of the Harry Potter books.

Guests at the five-star Balmoral Hotel in Edinburgh3 pay upwards of £1000 to stay in room 552, much more than the rate for other rooms. Why? Because that's where Rowling famously checked herself in to finish the final volume of the Harry Potter series. In an interview with Oprah Winfrey4 in 2010, Rowling explained how she needed to remove herself from everyday life to stimulate deep creativity.

. . . there came a day, the window cleaner came, the kids were at home, the dogs were barking and I could not work. And, this lightbulb went off in my head, and I thought, I can throw money at this problem. I can now solve this problem. For years and years and years, I could go to a cafe and sit in a different kind of noisy work. I thought, I could go to a quiet place.

Going to Tahoe worked for me largely because it was such a significant gesture. It's a four-hour drive from my home in the San Francisco Bay area and it cost quite a chunk of change. But I have friends who have converted garden sheds available at Lowe's and Home Depot for several hundred dollars into creative studios right in their backyards. Other friends have rented campsites and set up a pop-up creative shop complete with batteries, solar recharging stations, and even generators.

Consider making an investment in a getaway space as you begin to develop your deep work rituals. This can be a great shock to the creative system, forcing it to focus and providing fantastic positive reinforcement about how valuable disciplined deep time will be.

I found that once I had built up my deep work muscles this way, I was able to focus deeply at the office, too, and even at home. I'd lock myself in a room in the basement and come out only for pre-timed breaks.

©Stil

Establish the Time and Scope of Sessions. It's also extremely helpful to plan the duration of your sessions and to set a goal for your output per session. I would dedicate sessions to completing specific sections of the chapters of this book, with a rigorous plan for word count, and as I learned how much time it would take me, with my new focus, to write the amount of words that I was happy with, I fine-tuned my scheduling of sessions accordingly.

Establish the Time and Scope of Sessions. It's also extremely helpful to plan the duration of your sessions and to set a goal for your output per session. I would dedicate sessions to completing specific sections of the chapters of this book, with a rigorous plan for word count, and as I learned how much time it would take me, with my new focus, to write the amount of words that I was happy with, I fine-tuned my scheduling of sessions accordingly.

Construct a Creativity Support System. Gather everything you will need to help you keep your energy up and stay comfortable and focused during your sessions and make sure you've prepared the environment. Obviously, turn off your email and phone. That's your bare minimum environmental control. I always bring my favorite monitor with me; make sure I have coffee, water, and some snack food at hand (and sometimes champagne, if I'm feeling celebratory, like if I'll be finishing a chapter); bring an exercise recording so that I can take quick workout breaks by my desk; classical, old school jazz and lo-fi music playlists loaded; and if I'm working in a public space, headphones.

Construct a Creativity Support System. Gather everything you will need to help you keep your energy up and stay comfortable and focused during your sessions and make sure you've prepared the environment. Obviously, turn off your email and phone. That's your bare minimum environmental control. I always bring my favorite monitor with me; make sure I have coffee, water, and some snack food at hand (and sometimes champagne, if I'm feeling celebratory, like if I'll be finishing a chapter); bring an exercise recording so that I can take quick workout breaks by my desk; classical, old school jazz and lo-fi music playlists loaded; and if I'm working in a public space, headphones.

What would your list look like?

My list:

The Value of not Working Alone

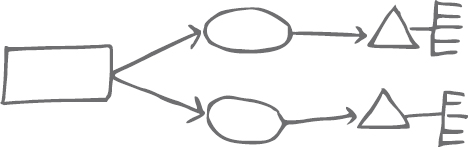

Once you have developed your ability to reliably dedicate yourself to deep work in your dedicated getaway space, you should try spending some creative time in one of the wealth of open workspaces that have cropped up. This allows for working in a manner Cal Newport calls the hub-and-spoke model. The idea is to place yourself in a creative space with others who possess disparate skillsets, mindsets, and goals.

Place yourself in a creative space with others who possess disparate skillsets, mindsets, and goals.

Working in these spaces can be challenging at first. They can be like cafes, with lots of conversations, clanking of glasses, and hubbub of chairs being moved around. But whereas at cafes, usually most people are there to enjoy cappuccino and pastries, or have meetings, with only a minority there to work alone, in open workspaces everyone is there primarily to work. You're surrounded by people who also need to toggle between deep and shallow work. That creates the opportunity to make great creative use even of your shallow time. Because open workspaces are talent pools.

Plug into the serendipity of the space to stoke creativity by exposing yourself to all sorts of interesting people doing interesting things.

The idea of a hub-and-spoke model is to have a dedicated quiet space for doing your deep work, which most of the spaces offer, and then to plug into the serendipity of the space to stoke creativity by exposing yourself to all sorts of interesting people doing interesting things during the time you come up for air. Meeting other people engaged in creative work can be so stimulating. Creativity is buzzing all around you, and you are perked up by the creative energy. You meet people working on some of the most amazing projects, and they can share ideas that can help you take your work in even more exciting directions. Such encounters often lead to creative collaborations. Working in these spaces can also create a healthy sense of competition, encouraging you to get the most out of your deep work dives so that when you emerge you feel pleased with yourself and a rightful member of this creativity hub.

©Angelo Pantazis

I learned the benefits of working in a creativity hub early in my writing career. As I was developing the manuscript for Engage!, I leased a second office space to place myself right in the thick of the creative outburst that would come to be called Web 2.0. All around me, people were creating the innovations that have so profoundly shaped our lives. The building was located in the San Francisco SoMa district, on Second St., and was packed with tech startups. Creativity coursed through the place. Innovation was happening in every room. The concentration of game-changing companies and leaders, both in my building and across the street in South Park and around the neighborhood in many converted open workspaces was incredible. Simply going out to get lunch or dinner, or to pick up coffee, you couldn't help but overhear people discussing brilliant ideas for some new program or invention that would become the next new big thing.

I was challenged to push my creative boundaries. I learned powerful new skills, like online design. My point of view broadened and I was constantly inspired. I benefited from so many happy accidents.

If you develop the discipline to dive into deep work within these open work environments, you won't be distracted by all of the activity; you'll be rejuvenated and re-energized for a next deep dive.

©Emma Matthews

Ruthlessly Prioritize

To make time for deep work, you've got to implement a process of extremely strict prioritization of what you will work on, stripping out most, if not all, nonessential obligations and time-sucks.

To make time for deep work, you've got to implement a process of extremely strict prioritization of what you will work on, stripping out most, if not all, nonessential obligations and time-sucks. In researching how highly productive creative people do this, I came upon the story of Fidji Simo, vice president of product at Facebook. Her rapid ascension within the ranks of such a highly competitive company is widely admired within the tech circles. In a profile in First Round Review,5 she shares lessons she had learned about creative productivity when she was facing what threatened to be a long stretch of downtime.

She manages a team of 400 product managers and engineers developing some of the most successful products that we all, for better or for worse, use on a regular basis. Just a couple of years ago, however, she was ordered to bedrest for five months during a complicated pregnancy. At the time, she was in the midst of a number of critical projects, and she decided that she would not take a leave of absence. Instead, she would work from home. She recalled in the article that, “It required immense focus. I actually felt so much more productive than when I was in the office.” The article explained:

Working remotely meant she was forced to say “no” to anything that wasn't critical, which created the time and space—physically and mentally—to put 100% of her effort toward the most pressing and important projects. By cutting out anything nonessential she was able to focus on the most strategic priorities, not only for the product team, but for herself. When she returned, she brought this commitment to focused work with her—eager to share it with her team

We can all benefit from adopting her practices.

- She schedules every aspect of her work, including time for handling unforeseen interruptions. All too often, urgent meetings, calls, and emails sneak their way on to your calendar, hogging up critical deep work time. Acknowledge this reality by scheduling some time for intrusions. “My calendar is my most powerful tool for enforcing my prioritization,” Simo says. She plans for two hours of “buffer time” each week for unscheduled interruptions, and then she allocates it with strict prioritization, postponing any requests for her time that she can schedule for later. Of course, no one wants to hear that their request, need or time is not important to you. Communicating well here is key. Simo suggests the following ways to respond:

- What to say when something can wait: “I'm focused 100 percent on x this week, so if this isn't an urgent issue, let's re-evaluate next week.”

- What to say when you need a little time: “I'm fully focused on x right now, so I can't meet about that this week. But if you send me an email, I will get back to you with an answer by y.”

- What to say when someone else can handle it: “This week, I need to focus all my time on x, but if you need an urgent answer, you can reach out to my team lead, z, who is focused on that issue.”

©Martin Shreder

- She concentrates her deep work time entirely on the most important project on her agenda.

- She schedules “clarity” check-ins for herself, between 30 to 60 minutes each, to review her prioritization of tasks and assess if she's on course with her goals and prioritizing right for her team. Simo's drill for this is:

- List the broader team or organization's top priorities.

- Check that your personal priorities for the week still align with those priorities.

- Check for any new information or data that requires a shift in priorities.

- Check priorities against your time allocation, meetings, and commitments that week.

- Make any adjustments to your calendar to better reflect your priorities.

- Note any priority adjustments that impact or need to be communicated to your team.

You can adapt her process in any way that's best for your work.

- For meetings, which we all know can be such unproductive time thieves, she advises: Have a clear agenda for what you want to achieve or what needs to be achieved in every meeting. Also, maintain a checklist of objectives that you want to leave each meeting with.

- Simo has also, vitally, made time for her personal creative expression. She shared that she is a painter, but she hadn't made time for it in years. She missed the happiness she felt when making her art, and by being so rigorous with her work schedule, she was able to create time for it again. She explained,

I decided to do one art project a week. You would think finding the time to stick to it was the harder part, but it wasn't. What was hard was realizing that being creative was one of my core goals—it was being honest with myself about my priorities first and then enforcing them going forward.6

Diving into Flow

Building your ability to focus creatively is like holding your breath. The more you practice it, the more you increase your ability to hold longer and deeper breaths.

By rigorously carving out time for deep work, you will create the condition for experiencing regular episodes of flow, which can become deeper and richer the more you dive in. Recall that the state of flow is characterized by:

- Removal of interference of the thinking mind.

- Complete involvement in what we are doing.

- A sense of ecstasy—of being outside everyday reality.

- Great inner clarity—knowing what needs to be done, and how well we are doing.

- The confidence that the activity is doable, that one's skills are adequate to the task.

- A total lack of self-consciousness. There's a sense of serenity—no worries about oneself, and a feeling of growing beyond the boundaries of the ego.

- Timelessness—one is so thoroughly focused on the present that hours seem to pass by in minutes.

- Intrinsic motivation—whatever produces flow becomes its own reward.

©Sasha Stories

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi says7 flow is “a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience is so enjoyable that people will continue to do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it.” That's the ecstasy of it, and the marvelous thing is that we can achieve deeper and deeper experiences of that ecstasy. We can become flow free divers.

Free divers swim to extreme depths underwater (the current record is 214 m) without any breathing apparatus. Champions can hold their breath for extraordinary amounts of time—the record for women is 9 minutes, 11 for men.8

Have you ever wondered what pushes the insane progress in adventure sports? I think back to my teens and early 20s growing up in Southern California and surfing Point Dume and Zuma. I think the biggest wave I rode then was a massive wall with a face of four feet. (Hey, that was big for me!) And at the time, I think about the pros who were conquering massive 25-foot waves around the world (especially in Northern California at Mavericks). Nowadays, surfers are pushing more than three times that. In November 2017, Brazilian surfer Rodrigo Koxa broke the Guinness World9 record by riding an 80-foot wave. This beat the previous record10 held by American surfer Garrett McNamara (78 feet). These types of incredible leaps forward have been achieved in many sports.

How do these super humans perform these otherwise unimaginable feats? According to Steven Kotler,11 author of The Rise of Superman: Decoding the Science of Ultimate Human Performance, the secret lies in the ability to engage in the state of flow.12 He highlights that when people are in flow, their “. . . mental and physical ability go through the roof, and the brain takes in more information per second, processing it more deeply.”

Our nervous system is incapable of processing more than about 110 bits of information per second. And in order to hear me and understand what I'm saying, you need to process about 60 bits per second.

That's why when we're in flow, we are totally unaware of distractions. Csikszentmihalyi explains the science of this.13 “It sounds like a kind of romantic exaggeration,” he says. “But actually, our nervous system is incapable of processing more than about 110 bits of information per second. And in order to hear me and understand what I'm saying, you need to process about 60 bits per second.” He continued, “That's why you can't hear more than two people. You can't understand more than two people talking to you.”

When your mind is so focused on the processing it's doing for your creative deep work, it simply has no frequency left over for anything else.

When your mind is so focused on the processing it's doing for your creative deep work, it simply has no frequency left over for anything else. Even for noticing while you're in flow that you're in flow.

Whenever I think about this aspect of flow, I can't help but think of a wonderful scene in the movie Finding Nemo. Nemo's father, Marlin, is trying to find the East Australian Current, so he can get to Sydney super fast to look for his son. The current is the River Rea, by the way. It's a river within the ocean that's 100 km wide and 1.5 km deep, and though it moves more slowly than is depicted in the film, it courses at an impressive speed of 7 km per hour.

In the scene, Marlin calls out to a turtle racing by near him, “I need to get to the East Australian Current,” and the turtle replies, “You're ridin' it dude!”

The best moments usually occur when a person's body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.

We can think of the state of flow as what the founder of the field of Positive Psychology, Martin Seligman, calls optimal experience, a kind of perfection. He writes, “The best moments usually occur when a person's body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile,” and that,14 “Consciousness and emotion are there to correct your trajectory; when what you are doing is seamlessly perfect, you don't need them.”15

While our creative output will never actually be perfect, we can have a perfect experience while we are making it. And we can even strive to be in flow more often and for longer periods. We can even become what Csikszentmihalyi calls an “autotelic” person,16 which he describes as being “never bored, seldom anxious, involved with what goes on and in flow most of the time.” He further explains,

Autotelic17 is used to describe people who are internally driven, and as such may exhibit a sense of purpose and curiosity. This determination is an exclusive difference from being externally driven, where things such as comfort, money, power, or fame are the motivating force.

We can achieve this state of being by constantly challenging ourselves, strengthening and gaining new skills, opening ourselves up to feedback so that we're aware of how we're performing, and having well-defined success metrics to evaluate our progress.

Keep Score to Keep Improving

Your Performance

Cal Newport likens working deeply to the process of business governance. Businesses seek to carefully allocate their investments, of resources and their people's time, in order to maximize their return on those investments (ROI). In order to provide yourself with the feedback you need to evaluate your progress in developing your creative productivity, you've got to devise a way of measuring your return on your time and mental, spiritual resources. I advise creating a creativity scorecard. This tracks daily and weekly measures of achievement of your goals.

In order to provide yourself with the feedback you need to evaluate your progress in developing your creative productivity, you've got to devise a way of measuring your return on your time and mental, spiritual resources.

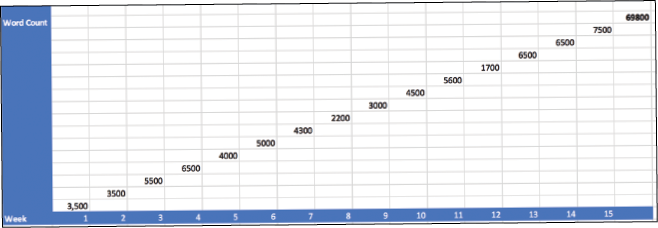

This may sound intimidating, but it can be a very simple tracking of where you are versus where you need, or want, to be. Here is an example of the scorecard I used to track my progress in writing this book:

You can't imagine how motivating this simple tracking of word count was to me.

I developed this concept based on the work of Chris McChesney, Sean Covey, and Jim Huling, the authors of the influence book The 4 Disciplines of Execution. The book is designed to help business people execute on plans “in the midst of the whirlwind of distractions.”18 Their key tips for scorecards are that they should:

- Be simple

- Be visible

- Show clear indicators of your performance

- Tell you immediately if you are on or off track

- Be regularly updated, ideally either daily or weekly

This simple personal accountability device will allow you to see exactly when you're falling short and that helps pinpoint why. It also lights a fire of creative determination.

To show you how eye-opening this tracking can be, I'll share a very embarrassing earlier version, from when I was struggling to make any progress on the book project I had thought would be my next one. This graphic representation of how far off the mark I was of the goals I had set for myself for the hours needed to generate targeted word counts helped me realize that I had to take a serious look at what was going wrong with my creative process.

The scorecard shows the words I wrote versus my goal and how much time I spent measured against the time I estimated I would need to write that amount. You can see there are glaring gaps between my goals and actual output. What this scorecard doesn't represent is the number of times I stopped my Pomodoro timer in the middle of a deep work block to chase digital distractions.

The wake-up call I got from this helped me to see all of the other self-defeating consequences of my distractions. It helped me to appreciate just how much less time I could spend with my family—all those extra hours over the time I had estimated—and that helped me to take the hard look I needed at all of the negative effects on my life, and that of my family, from failing to nurture my creative energy.

On the flip side, once I had begun applying the insights I gained from researching this book, when I set out to go ahead and write it, you can see the steady progress I made. What that scorecard taught me was that there's a great sense of accomplishment in gaining control over your creative productivity, even from the smallest strides toward achieving your goals.

It's important to be diligent about measuring and charting your progress as you go. Measuring your progress not only helps inspire you, it allows you to calibrate the goals you've set for yourself better with your current skills, and that helps you to get into flow.

We get better and better at taking on new challenges, understanding that we've got to apply ourselves to developing skills that will allow us to carefully balance the difficulty of our creative mission with our ability to achieve it.

“It is not enough to be happy, to have an excellent life,” Csikszentmihalyi states. “The point is to be happy while doing things that stretch our skills, that help us grow and fulfill our potential.” I couldn't describe the goal of lifescaling any better.

“It is not enough to be happy, to have an excellent life. The point is to be happy while doing things that stretch our skills, that help us grow and fulfill our potential.”

-Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

Notes

1https://productivephysician.com/deep-work/#Deep-Work-The-Rules

2http://vedanta.org/become-a-monastic/

3http://philosophicaldisquisitions.blogspot.com/2016/01/the-value-of-deep-work-and-how-to.html

4https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GjLan582Lgk

5http://firstround.com/review/how-facebooks-vp-of-product-finds-focus-and-creates-conditions-for-intentional-work/

6Ibid.

7Cskikszentmihalyi, Flow, 1990, p.4

8http://theconversation.com/free-divers-have-long-defied-science-and-we-still-dont-really-understand-how-they-go-so-deep-92690

9http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/news/2018/5/a-timeline-of-the-biggest-waves-surfed-as-rodrigo-koxa-sets-new-record-523752

10https://www.independent.co.uk/sport/general/rodrigo-koxa-video-surf-biggest-wave-world-record-surfing-watch-nazare-beach-portugal-a8329466.html

11https://www.fastcompany.com/3031052/how-to-hack-into-your-flow-state-and-quintuple-your-productivity

12https://www.fastcompany.com/3031052/how-to-hack-into-your-flow-state-and-quintuple-your-productivity

13https://www.ted.com/talks/mihaly_csikszentmihalyi_on_flow/transcript?language=en#t-332434

14Csikszentmihalyi, 2002, p. 116

15Csikszentmihalyi, 1990, p.3

16https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/autotelic

17Cskikszentmihalyi, 1990, p.67

18https://www.amazon.com/Disciplines-Execution-Achieving-Wildly-Important/dp/145162705X