10

WHEN DOVES CRY

MOST FONT ENTHUSIASTS SHUDDER WITH horror at the thought of a certain old man strolling across the River Thames in the autumn of 1916. The dark figure labors to make his way to the railing of Hammersmith Bridge by night. His deliberate gait signals that he’s carrying a heavy burden. And from his journals, we know that he’s been suffering from severe depression. “I have been in the depths of despondency,” the seventy-six-year-old man writes, “I have no longer, as it seems to me, any essential place or function in the world. I have played, or am playing, my last cards.” That man is one of the key players of the Private Press Movement, and he is about to do something terrible.

A witness like you might try to call out to the old man, but the septuagenarian will not listen. He struggles to pull himself up onto the railing and, with a final heave, lets his burdens go. “No!” you cry out, just before the splash—and then another splash, and another and another. Your cry trails off as several splashes dot the surface of the dark river. Now the old man doesn’t appear depressed at all. He snaps closed the box he was carrying and scampers off, giggling like a schoolboy.

What in the name of Johann Gensfleisch zum Gutenberg just happened?

Was the old man just littering? In reality, he was guilty of far worse than a petty dumping violation. He has just effected the destruction of one of the world’s most beautiful fonts: the Doves Type. The shadowy figure behind this crime was none other than its devoted owner, T. J. Cobden-Sanderson.

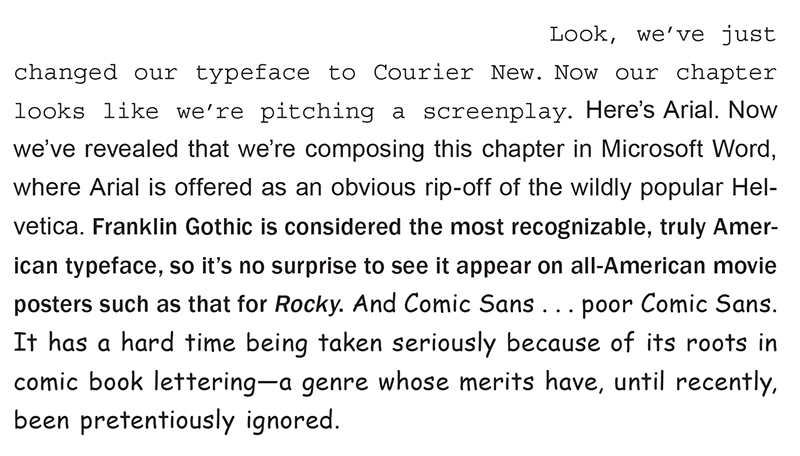

Today we largely take typefaces for granted. In fact, we’re kind of supposed to. Many designers argue that a font must do its “work and disappear.” Yet that’s not entirely accurate. We have countless typefaces, each telling its own story, each making us react differently, whether we realize it or not.

The typographer Erik Spiekermann compares typefaces to footwear: Sure, they’re all accomplishing the same general purpose, but steel-toe boots send a very different message from ballet shoes. Change the typeface and you change the message.

Some typefaces imply honesty, like Gotham. This typeface is known for its “unremarkability and inoffensability,” which the 2008 Obama campaign used for its action words such as HOPE and CHANGE. This was “a type consciously chosen to suggest forward thinking without frightening the horses.” Some typefaces have a trustworthy and authoritative air, such as Baskerville, which a recent study has indicated makes you 1.5 percent more likely to agree with a given statement.

Today, dozens of typefaces are available on our word processors, and hundreds upon hundreds more are easily accessible for download. Until recently, though, the ultimate font of cold beauty, the Doves Type, was probably the most elusive of all. Its owner, Cobden-Sanderson, guarded it with religious zeal. Then, rather than let his type fall into commercial hands, he destroyed it. All of it.

What led Cobden-Sanderson to hurl his legacy from a bridge is one of the more surprising stories in the history of print. As the adage goes, If you love something, drown it in the Thames. If it comes back to you, it won’t, because you drowned it in the Thames. To really understand the reasons behind Cobden-Sanderson’s destruction of the Doves Type, we have to look at his decade-long feud with ex-partner Emery Walker, and the origins of the Private Press Movement.

BORN THOMAS Sanderson in 1840 in Northumberland, England, he spent the first forty years of his life bouncing from locations as diverse as shipyards to Cambridge University, trying his hand at myriad occupations and failing because of dissatisfaction and recurring mental breakdowns. The artistic temperament in him seemed wholly incapable of dealing with the ho-hum life of a typical Victorian Londoner.

During a trip to Italy to recuperate from his latest downturn, he met Annie Cobden. In 1882 they married, taking each other’s last names. Annie seemed a good counterpoint to T.J., and she encouraged him to follow his dreams. This is the history of print, so his dream was, obviously, to be a bookbinder.

To Cobden-Sanderson, bookbinding was “something which should give me means to live upon simply and in independence, and at the same time something beautiful.” There are certainly worse ways to make a living. After a decade spent mastering bookbinding, the Doves Bindery opened in March 1893, when Cobden-Sanderson was a strapping fifty-three years old. Some nineteenth-century Londoners hit their midlife crisis and run out to buy a two-horsepower convertible Victoria with drop-down front benches. Others start a bookbindery. To each his own.

Cobden-Sanderson named his bindery after the building’s location, a pleasant lot called Doves Place. Modern collectors buy certain books for their bindings alone, and Cobden-Sanderson’s are some of the most highly sought after. They are exceptional for their aesthetic unity, the quality of their materials, and their high standard of finishing. Cobden-Sanderson’s style is so valued that you can even find known counterfeit Doves bindings floating around the market, commanding high prices themselves, forgery notwithstanding.

Before about 1800, the components used for printing books remained surprisingly stable for three hundred years or more. Over the centuries, the book very slowly transformed into a popular commodity, rather than the expensive luxury of its earliest days. But by Cobden-Sanderson’s day, the technology of print had experienced an unprecedented rate of evolution.

As economies and audiences shifted, consumer demand took off. Publishers needed to put out more product, and do it as fast and as cheaply as possible—which sounds like a job for your friendly neighborhood Fourdrinier paper making machine, or Koenig rotary press, or the game-changing Monotype. Every aspect of bookmaking was tinkered with to improve efficiency. The traditional world of book production—handmade papermaking, hand presses, and hand-set type—was vanishing behind a veil of steam, steel, and grinding gears.

The aforementioned Fourdrinier machine used a moving belt and felt rollers to make paper of any width or length. Thanks to this contraption, by about 1810 machine-made paper was being regularly produced and sold. Hot on its heels, on November 28, 1814, The Times in London printed its newspaper using newly mechanized presses developed by Frederick Koenig. Instead of the up-and-down, stamplike movement of a traditional press, Koenig placed the sheet around one cylinder, which was then rolled against a second cylinder. This double-cylinder, steam-powered press represented the first major change in the fundamentals of the printing press since its invention—and more than tripled its productivity. Now you’ve created a mechanized printing assembly line. These presses worked so quickly that daily newspapers were no longer constrained to eight pages per issue, the largest practical capacity that older metal types could handle.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, casting type jumped from around four thousand sorts (individual pieces of type) in a day by traditional hand molds to six thousand an hour on specialized typecasting machines. With the invention of the Linotype in 1884, type was cast with the press of a button, using a “hot metal” process. With this machine, printers could instantly create a “line o’ type” using a two-hundred-pound appliance that was “kind of a cross between a casting machine, a typewriter, [and] a vending machine.” Its companion, Monotype (casting single letters with the hot metal process), would soon revolutionlize the industry of typefaces.

These new machines, among many others, dramatically accelerated the capacity for mass production in the nineteenth century. If you’re looking to create a large number of books, these machines were perfect. There are drawbacks when it comes to mass production, however. A product can be fast, cheap, or good. It can be a combination of two, but it can’t be all three. In the nineteenth century, most publishers chose fast and cheap. The results were not what one would normally call “good.”

Enter the rebels of the printing world. As early as 1639 there is documentary evidence of printers who worked for pleasure only—for the beauty of their craft—not for the golden god of profit. These rebels “form a distinct undercurrent” running throughout the history of print. Yet, in the Industrial Age, that curious dissent transformed into a full-fledged rebellion. Especially among the alliance of printers who saw themselves as artists rather than assistants to Linotype machines.

Most scholars identify the start of the Private Press Movement with a lecture given at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society in London on November 15, 1888. The timid speaker was Emery Walker, the . . . let’s say, Yoda of that rebel alliance. Walker was a photoengraver, successful businessman, and vocal advocate of returning printing to its high-quality roots. He had been invited to present this lecture by fellow society member T. J. Cobden-Sanderson. T.J. can be Luke Skywalker, here, if you want—the printing Force was strong with that one.

Walker’s address had a profound impact on the world of fine printing. What may seem like a grumpy old man’s lecture about things “being better back in the day” was in fact a thrilling and inspiring call to arms. It sparked the creation of an entire community dedicated to examining every aspect of print, and finding a way to make the results as transcendent as possible. Most immediately, it inspired William Morris, the Pre-Raphaelite poet and textile designer, to start the Kelmscott Press, which specialized in limited edition, hand-pressed books of exquisite beauty.

Using a font he designed himself, and employing just two compositors and one pressman, Morris printed what has been called the first book of the Private Press Movement in 1891: his own novel The Story of the Glittering Plain. Morris’s Kelmscott Chaucer, considered the masterpiece of that press, is often credited as a front-runner for the Most Beautiful Book in the World. Colin Franklin noted in 1969 that “[b]ooksellers take its current price for an index of the state of the nation,” and that assertion is still pretty accurate in some circles today.

Meanwhile, Emery Walker presided behind the scenes, as he would for many of the most important printers of the Private Press Movement. Walker was the de facto silent partner behind Kelmscott; according to Morris’s sometime private secretary Sydney Cockerell, “no important step was taken without [Walker’s] advice and approval.” When T. J. Cobden-Sanderson ventured into printing himself, his business partner was none other than Emery Walker.

The Private Press Movement lasted approximately from 1891 to the end of the Second World War. In all things, it was a rebellion against the impersonal mechanization of modern printing. It was a revolution of beauty. And if you were going to choose a revolution from the 1800s to throw your support behind, the one that results in artisanal books is probably better than ones that end in guillotines, political xenophobia, or ethnic cleansing.

The inspiration for this printing revolution was the books of Gutenberg’s day, which were, in comparison to industrial age volumes, gorgeously fabricated and meticulously designed, from the viscous black ink and the carefully sculpted type to the hand-sewn bindings. Even in Gutenberg’s day, though, machines were used to produce commodities on a mass scale. Herein lies the irony. Machines can’t be all bad: the printing press itself is a machine. So how much mechanization is too much mechanization? The rebels who ran private presses rarely agreed among themselves on any particular detail.

One characteristic starkly separates fine press printing from mainstream printing: its ultimate goal. Whereas big publishers were out for profit, fine presses cared about making high-quality books—profits and nice clothing and warm houses and food be damned. The money made by presses such as the Doves Press barely factored into anyone’s considerations because they cared about only the elegance of the final product. On this point both Walker and Cobden-Sanderson were firmly in agreement. As a result, these presses created some of the most stunning books the world has ever seen, but it also made running a business difficult. Always short on cash, the Doves Press closed five years before Cobden-Sanderson’s death. Its parts were sold off for just eighty-seven pounds—about 18 percent of its total start-up cost.

Even if Cobden-Sanderson could have foreseen the meager finances coming to him, he wouldn’t have cared—at all. His wife, Annie, might have cared a little because she funded the Doves Press with her inheritance, but Cobden-Sanderson was a rebel with a cause. And that cause was gorgeous books. Or, as he described it, “The Book Beautiful.”

Like other pieces of art that are sold as commodities, over the centuries books have been balanced precariously between “sacred vessels of Western culture” and “show me the money!” Both philosophically and monetarily, books are most often valued for what’s written inside them. Still, we have a natural urge to make something physically beautiful in order to demonstrate its value to us. Some of us take that a bit further than others. For Cobden-Sanderson, money was entirely beside the point. Books themselves were divine: “This is the supreme Book Beautiful . . . a dream, a symbol of the infinitely beautiful in which all things of beauty rest, and into which all things of beauty do ultimately merge.”

Good heavens, where can someone buy a piece of this sublime portable universe, marching ceaselessly through time and space? Answer: at the Doves Press sometime in the slim sixteen-year window of its operation. In October 1902 the Doves Press completed its original printing of John Milton’s Paradise Lost. It was called by the famed English bibliographer A. W. Pollard “the finest edition . . . ever printed, or ever likely to be . . . I know no more perfect book in Roman type.” He’s really not exaggerating. You can expect to pay a few thousand dollars to obtain one today.

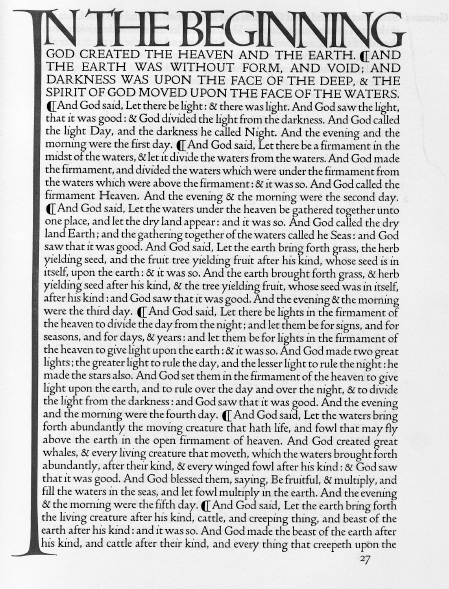

THE DOVES PRESS BIBLE, 1903–1905. Image courtesy Heritage Auctions.

Cobden-Sanderson next tackled the Bible. “In the beginning God created Life,” he explained. “And it is this Life, this Life of each and of all of us, which in the language of the Press, we must COMPOSE.” Between 1902–05, the Doves Press composed life.

The clear, stark beauty of this page feels like a marble statue translated from stone into paper. In person, it is breathtaking. Anyone talking around you suddenly sounds like the adults in Peanuts cartoons, a dull, irritating wah-wah-wah next to the presence of the book in your hands.

This lofty rhetoric may seem a bit hyperbolic to people who view books as . . . just books. To the untrained eye, though, the simplicity is deceiving: “[The] masterly calligraphic initials, like the unforgettable opening of Genesis . . . were a perfect example of how to marry calligraphy and typography, and [the] setting was full of those almost invisible refinements that only another printer can recognize.”

To Cobden-Sanderson and the revolutionaries of the Private Press Movement, books were the summit of artistic expression. What value had money when compared to the realization of humanity’s true potential? It was dross, we tell you, shiny, metal dross. At least, that’s how Cobden-Sanderson felt about it. His business partner had a more complex view.

Emery Walker may have been the Yoda whose speech sparked the Private Press Movement, but he was still a competent businessman. Two men can run a print business together, sure, but it’s a bit harder if one is an artist with his head in the clouds and the other is a leader with a plan. Initially, it seemed that Cobden-Sanderson and Walker shared the same philosophy. For example, they both formally agreed to be paid in books. “[Cobden-Sanderson] and Emery Walker were simply to share the work, and, in return, each of them would receive a copy on vellum, and a dozen copies on paper, of the books they printed. If there were any profits after expenses, these would be divided equally.” Profits were like getting to the end of a bag of Halloween candy. The valuable stuff has already been divided—vellum copies of Paradise Lost might be the full-size Snickers bars here—and all that’s left are those awful rainbow-colored Tootsie Rolls and bite-size Milky Ways. Fine, take half of those. No one wanted them, anyway.

Both Walker and Cobden-Sanderson believed in producing beautiful books before profit. So far, so good. But pretty soon their differing philosophies rose to the surface. In particular, Walker believed he was an equal partner in the Doves Press. Cobden-Sanderson believed he was an idiot for thinking that.

Emery Walker may have brought some much-needed business savvy to the operation (along with a list of potential subscribers from the neighboring Kelmscott Press), but Annie had paid for everything, and Cobden-Sanderson was doing most of the work. The most serious dispute between the partners wasn’t over profits. It was the fight on principle for ownership of the most important product to come out of their joint venture: the elegant, pristine, chills-inducing Doves Type.

BESIDES THE influence of technical designers and punch cutters, the Doves Type is a combination of two different typefaces dating back to fifteenth-century Italy, as well as Cobden-Sanderson’s personal touch to the numerals. The Doves is a mirror of its unique time and place. While it reflects the reverence that printers such as Walker and Cobden-Sanderson paid to the pioneers of print in the fifteenth century, details have been subtly changed to make it as refined as possible to the early twentieth-century eye. It is the Private Press Movement in a nutshell.

What was true of the Doves Type is true of typefaces from any age: they are reflections of their culture. Even before print, the script we call Gothic developed in the Late Middle Ages as a way for scribes to write faster when the rise of universities increased the demand for books. In a time before paper came into common use, this script also produced writing in a more compressed form, to save on expensive parchment. In fact, it was originally called textura because the compressed style gave it a woven appearance. Gutenberg’s typeface in the first printed Bible was inspired by textura scripts.

We call typefaces like these “Gothic” because of the cultural shift that took place in the Renaissance. Gothic was “a term of derisive abuse which the Italian humanists applied to the traditional script of their contemporaries . . . [I]t was only meant to signify the classicist’s contempt for the barbarism of those who neglect to follow the Roman models as the Goths and Vandals did.” In other words, our modern name for this font family is a Renaissance-era insult aimed at the Middle Ages.

No matter the time or culture, our fonts change with us. In order to define themselves against the rest of the world, for example, early twentieth-century German patriots advocated the use of Gothic fonts. These fonts were deeply tied to major moments in the German literary tradition, such as Martin Luther’s 1523 translation of the Bible. Maybe you can guess where this is going. With the Nazi Party’s rise to power, Gothic fonts became part of the Propagandamaschine. Here’s a real slogan from the time: “Feel German, think German, speak German, be German, even in your script.”

In 1941, however, German script suddenly changed. Gothic type was labeled Jewish. “The type [was] being newly associated with the documents of Jewish bankers and the Jewish owners of printing presses.” That may have been true, but there were other causes as well. According to Erik Spiekermann, there was actually a shortage of fonts in Gothic typefaces; moreover, conquered territories were having trouble reading it. In other words, Gothic became too impractical. What’s the point in conquering a nation if the people can’t read all the horribly racist posters you keep putting up? The dominance of Roman typefaces in German books today is partially thanks to the lack of printing supplies in the Nazi Party.

The typefaces of the Private Press Movement reflected the concerns and the culture of the period. William Morris’s work at the Kelmscott Press, which many people write off as simply too much, expresses a powerful printing philosophy. The pages are densely pressed, covered with elaborate woodcuts and a typeface almost too pretty to read comfortably. One fellow printer calls them “full of wine.” This style was meant to be beautiful, yes, but it was also meant to create an “alienation effect,” that is, an extreme statement meant to force a reaction. Morris wasn’t simply suggesting his opinion; he was screaming it. It was this barbaric yawp that led the rebellion like a battle cry.

The moment of conception for the Doves Type probably occurred at a Sotheby’s auction in December 1898. About a year and a half before, William Morris had died. By the following spring, his Kelmscott Press had closed, and the inventory was slotted to be sold off. In his journal from December 11, Cobden-Sanderson wrote about the need to create a typeface for “the Book Beautiful.” Lucky for him, much of the movement’s original inspiration was contained in Morris’s collection of fifteenth-century books, which had just gone up for auction.

Two books in particular would have been of supreme interest to Cobden-Sanderson. The first was a copy of Historia Naturalis by the ancient Roman author Pliny the Elder, printed in Venice in 1476 by Nicolas Jenson. Jenson had created a Roman font for this book that has been described as “absolutely perfect,” and was imitated for the next four hundred years. William Morris used Jenson’s Historia Naturalis to create his first Private Press font, which he named the Golden Type. (Morris liberally altered Jenson’s typeface, to make it thicker and more gothic. Cobden-Sanderson wanted a return to the thinner, cleaner look of the original.) From Historia Naturalis, the capital letters of the Doves typeface were formed.

The lowercase letters also came from a fifteenth-century Venetian printer, one Jacobus Rubeus, who printed Historia del popolo fiorentino in 1476. There is some debate as to how much access Cobden-Sanderson had to the Jenson and Rubeus books while the Doves Type was being conceived, but this is where Emery Walker comes in. Walker had helped William Morris create his Golden typeface ten years earlier, by photographing and enlarging both historiae. Walker still owned those negatives.

One of Walker’s photoengraving employees, Percy Tiffin, used this material to redraw a set of letters and numerals that would become the artistic model for the Doves Type. But Edward Prince, the punchcutter, had to carve them in 3D. This was no easy task. A reader might be wondering, how hard could it be to re-create those typefaces? The letters were there on the page in front of them. Just, you know, sculpt them again. A book’s physical printing has an impact on how the typeface turns out, though. For example, how hard a letter is pressed into the page, or how much ink it has taken, changes the appearance of the type. Walker wrote that “nearly all of Jenson’s [letters were] . . . over-inked and gave an imperfect view of the type.” Prince had to “extract” their “true shapes” by hand from the various samples he was given.

Since the Latin alphabet doesn’t have a J, U, W, or its lowercase equivalent, those letters also had to be added. (Fun fact: Latin did have a w sound, but it was attached to the letter v. So that famous phrase attributed to Julius Caesar, “Veni, vidi, vici,” (“I came; I saw; I conquered”) would have been pronounced, “Weni, widi, wiki”—which sounds like something a Roman toddler might say after subduing the Pontic Empire under his bed.)

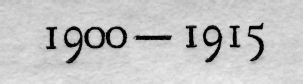

Cobden-Sanderson took issue with the numerals that Tiffin created for the Doves Type, so he consulted an acquaintance at the British Museum and finally approved a set that looks like the room numbers hanging in every classy hotel built between 1910 and 1940.

NUMBERS PRINTED IN THE DOVES PRESS CATALOGUE RAISONNé, 1914. From authors’ personal collection.

The Doves Type can’t adequately be called the creation of any one person. Two fifteenth-century printers provided the design of the letters; Walker owned the negatives and made revisions; Tiffin redrew the letters; Cobden-Sanderson directed much of the operation and tinkered with the numerals; punch cutter Edward Prince transformed those model drawings into actual metal characters that could be sunk into matrices and cast into type.

One of the terms of Walker and Cobden-Sanderson’s printing venture was that each partner should receive a font of Doves Type for his own use. By 1906, however, Cobden-Sanderson wasn’t in much of a sharing mood. After finishing the print run on the Bible, he wanted Walker out, and offered him a sum of money to forfeit all claims to the Doves Type.

More than a few red flags had popped up before this, signaling that their partnership wasn’t going so well:

• Cobden-Sanderson was nearly incapable of holding down a typical nineteenth-century job. Walker ran a thriving photoengraving firm.

• Cobden-Sanderson was a perfectionist with an artist’s temperament. Walker was a level-headed businessman.

• Cobden-Sanderson was “done to death’s door” by the amount of time he spent at the Doves Press. Walker checked in once a day, more interested in light management, without handling any actual presswork.

In a long letter written to Walker in 1902 (but never sent), Cobden-Sanderson outlined his grievances. When they started the press, they’d agreed to split the labor. Cobden-Sanderson would read the proofs, and Walker would oversee technical operations. It seems Walker wasn’t living up to his end of the bargain. To make matters worse, he was critical of typographical errors and design choices that were supposed to fall under Cobden-Sanderson’s jurisdiction.

Writing about their past projects, Cobden-Sanderson complained, “You objected to the spelling [in Paradise Lost], and you objected to the capitals in the text . . . to my arrangement of ‘In the Beginning’ and to the long initial I, and said ‘It will never do,’ you objected to the position of the title of the First Book of Genesis on the left hand page, and said it was ‘hateful.’”

We’re picking up a lot of angst here. By August 1902, Cobden-Sanderson wanted to dissolve the partnership completely. Since printing for the Doves Bible had just begun, he decided to bide his time. Three and a half years later, with the Bible behind them and his son, Dickie, working alongside him at the press, Cobden-Sanderson formally tried to buy out Walker’s claims to the Doves Type. Walker was less than cooperative.

It would appear that, for sole ownership of the type, Cobden-Sanderson upped his original offer from one hundred to three hundred pounds. It would also appear that Walker was like, uh . . . no. Whatever amount Walker countered with was apparently too rich for Cobden-Sanderson, and the negotiations broke down for the next couple of months.

The following February, a mediation of sorts was reached between the two partners—or, at least, that was Cobden-Sanderson’s impression. A mutual acquaintance drew up an arrangement that would allow for the end of the partnership in November 1908, and a payment of one hundred pounds to go toward the casting of a new font of Doves Type, if Walker so desired. He would later deny that he agreed to any of this. Which would have made any chitchat around the espresso machine particularly awkward over the next two and a half years, had Walker remained involved in the daily operations.

By this time, Cobden-Sanderson was in his late sixties. The sun rose and set on one thing in his world: fine printing. Everything else could take a long walk off a short pier, including personal acquaintances. “[Cobden-Sanderson] liked to watch plants and insect forms, to get new ideas for binding tools . . . he lost friends to whom his life looked peculiar. The new work became far more important than their small talk.”

On one occasion, Cobden-Sanderson completely lost it when turning down the leather on a binding. In his own words, “I found it too short, and in a burst of rage I took the knife and cut the slips and tore the covers and boards off and tossed them to one side; then, in a very ecstasy of rage, seized one side again, tore the leather off the board, and cut it, and cut it, and slashed it with a knife. Then I was quite calm again; made so, I think by the wonder and awe and fear that came over me as in a kind of madness.” Nothing odd about that—just re-creating the printer scene from Office Space because the headband on his binding was too short. It’s not as if he were serially prone to rash and destructive behavior. . . .

To Cobden-Sanderson, handing over the most beautiful font that had ever been created so that Walker could use it for a second Doves operation outside his control was tantamount to Private Press blasphemy. Here is the famed sword Excalibur. Should we use it to harvest wheat? Or perhaps chop firewood? Or maybe pick food out of our goddamned teeth? No sir, I tell you, no!

Cobden-Sanderson gave his six months’ notice to Walker in June 1908, which Walker promptly dismissed. Foreseeing the storm that was about to break, Cobden-Sanderson’s son, Dickie, quickly abandoned the Doves Press to work for an uncle.

Emery Walker agreed that the partnership had to end. But while Cobden-Sanderson wanted to continue his fine printing crusade, Walker thought the most prudent course of action would be shutting down the Doves Press, liquidating everything, and dividing whatever proceeds were left fifty-fifty. Considering what Cobden-Sanderson was willing to do to leather binding that was too short, we can only imagine the tour of human horrors playing out behind his eyes upon hearing that.

In December 1908, Cobden-Sanderson refused Walker further entry into the Doves Press. In June 1909, Walker initiated proceedings against Cobden-Sanderson in the High Court of Justice. On June 14, Cobden-Sanderson wrote, “[Walker’s] proceedings at the utmost can only result in ‘damages’ or imprisonment: and to think of that! for nothing on earth will now induce me to part with the type . . . I have the will, and I have in my actual possession the punches and the matrices, without which it is impossible to have a Font of Type . . . I am, what he does not appear to realize, a Visionary and a Fanatic, and against a Visionary and a Fanatic he will beat himself in vain.”

Two days later, their friend Sydney Cockerell brought them to the negotiating table. According to a new proposal, the partnership would be dissolved on July 23, and Cobden-Sanderson would be allowed to retain the Doves Type, to use at his discretion, for the rest of his life. Upon his death, however, the font would pass to Emery Walker.

So here you have two obstinate old men (Cobden-Sanderson, age sixty-nine; Walker, age fifty-nine) agreeing to a printing truce, each stubbornly attempting to outlive the other. It was basically the Highlander approach to font ownership. There can be only one!

Even as early as this truce, Cobden-Sanderson had secretly vowed that Emery Walker would never own his font, but its destruction wouldn’t happen for almost a decade. Emery Walker left the Doves Press in the summer of 1909, and Cobden-Sanderson and his wife, Annie, continued running it for the next eight years. The press itself wasn’t what you might call “profitable.” It was now worth less than its original investment, and Annie’s money, which was subsidizing the operation, had nearly evaporated. The printing house had to be closed and the press moved into the attic of the Doves Bindery. Annie and T.J. left their home so they could rent it for extra cash. In 1909, upon the advice of friends, Annie convinced her husband to begin printing the plays of Shakespeare. You know you’re involved in a snobby movement when printing Shakespeare is considered selling out.

The Doves Press ran for a total of sixteen years, from 1900 to the first few weeks of 1917. It is worth noting that there was no perceptible drop in the quality of Doves printing after Walker’s exit. For all the contacts and experience that he had brought to the operation, Cobden-Sanderson appeared to be the artistic visionary behind those Books Beautiful.

“It is my wish,” Cobden-Sanderson wrote back in 1909, “that the Doves Press type shall never be subjected to the use of a machine other than the human hand . . . or to a press pulled otherwise than by the hand and arm of man or woman.” In his “Last Will and Testament of the Doves Press,” written in June of 1911, a solemn Cobden-Sanderson decreed, “To the Bed of the River Thames, the river on whose banks I have printed all my printed books, I bequeath The Doves Press Fount of Type.”

Strangely enough, Cobden-Sanderson wasn’t the only printer who sank his font into the waters of the Thames. In 1903, Charles Ricketts of the Vale Press threw his original Vale Type into the same river. More than forty years later, the Brook Type used by the Eragny Press (with whom Ricketts had formal involvement) was cast into the English Channel. Was there something in the water that drove fine printers mad, compelling them to sacrifice their font to it? As Ricketts explained, “It is undesirable that these fonts should drift into hands other than the designer’s and become stale by unthinking use.” This is a rather common fear of type designers. What happens when you’re not around to guide its use? What if your beloved type ends up on a package of Charmin toilet paper? No one wants their baby to become the Toilet Paper Font.

Cobden-Sanderson’s destruction of the Doves Type began just before Easter, on March 18, 1913. Over the course of three days, Cobden-Sanderson walked to the edge of nearby Hammersmith Bridge and hurled the punches and matrices of his type into the river. The loss of these components, used to cast pieces of Doves Type, would have made it nearly impossible to re-create any new sets of the font. After a short break, Cobden-Sanderson revived his plan of destruction in 1914, just in time for the madness that was about to spread across Europe in the form of the First World War. The brooding Cobden-Sanderson cited the war two years later as he was erasing the last remnants of his font: “If I am foolish, well, what can be more foolish than the whole world? My folly is of a light kind.”

Knowing that the Doves Press would close forever at the end of the year, Cobden-Sanderson started the destruction of the font itself on August 31, 1916. “It occurred to me that it was a suitable night and time,” he wrote, “so I went indoors, and taking first one page and then two, succeeded in destroying three. I will now go on till I have destroyed the whole of it.”

The word page might be a bit confusing in this context. Cobden-Sanderson was talking about packets of metal type, each weighing over six pounds. Carrying twenty pounds of type the half mile between his house and the bridge in the dark, then heaving it over the side, would have been a moderately difficult feat for any seventy-six-year-old. When you envision a whole font of type, you might be picturing the total number of letters needed to fill up one of those old-timey partitioned printing cases. But when Cobden-Sanderson wrote that he was going to “go on till I have destroyed the whole of it,” he was actually talking about 2,600 pounds of metal type. In total, the Doves Type would have weighed more than a metric ton—and one very stubborn old man was determined to single-handedly destroy all of it.

At fifteen pounds (or two pages of type) per nighttime outing, Marianne Tidcombe estimates that Cobden-Sanderson took 170 individual trips to Hammersmith Bridge between August and January 1917 to do so. Sometimes he carried the metal type in linen bags, or wrapped in paper, but the most effective means was a converted wooden box with a sliding lid that he could overturn above the waters when he thought no one was watching.

“But what a weird business it is, beset with perils and panics! I have to see that no one is near or looking; then, over the parapet a box full, and then the audible and visible splash. One night I had nearly cast my type into a boat, another danger, which unexpectedly shot from under the bridge! And all night I feared to be asked by a policeman . . . what I had got in my ‘box.’”

Ignoring the obvious potential for physical harm incurred from chucking fifteen pounds of metal type off a bridge into passing boats, Cobden-Sanderson seemed genuinely enlivened by the criminality of his act. This despite running the risk of a potential jail sentence. With a hint of glee, he remarked, “Hitherto I have escaped detection, but in the vista of coming nights I see innumerable possibilities lurking in dark corners, and it will be a miracle if I escape them all.”

It was not so much a miracle as a question of no one caring about people randomly littering in the Thames. Before stepping forward to intervene, a Thames commissioner would have had to know all the details of Emery Walker’s suit against Cobden-Sanderson in the High Court of Justice, as well as the resulting arbitration.

Over the five months that it took to destroy the Doves Type, no one had the slightest inkling what Cobden-Sanderson was up to—not even his wife, Annie. If he hadn’t written with so much earnestness about his crime, the final whereabouts of the Doves font would have been lost to the ages. In addition to the sorts and the matrices and punches, Cobden-Sanderson burned most of the letters and other papers that had any connection to the Doves Press or the bindery. “I am determined that, as far as I am able to destroy, there shall be no debris left, no history of petty details, but only the books themselves.”

The Doves Press officially closed its doors on January 21, 1917. T. J. Cobden-Sanderson survived his press by only a few years, dying in September 1922.

Exactly twelve days after his death, Annie was contacted by Emery Walker’s lawyers and instructed to surrender the Doves Type, along with the punches and matrices, on pain of immediate litigation. In response, Annie published her husband’s will, wherein he detailed his intention to destroy the Doves Type. A lengthy spat of legal proceedings ensued that likely cost Annie upward of twelve hundred pounds. But the destruction of the Doves Type had been effected, and no amount of money was going to bring it back. Walker even attempted to hire Edward Prince, the original punch cutter, to re-create the lost font. But by 1922, Prince was seventy-six years old, and neither his eyes nor his hands were up to the task.

Cobden-Sanderson’s ashes were interred at the Doves Bindery in 1922. Annie’s ashes followed four years later. In 1928 the River Thames flooded its banks and washed through the building, so it’s likely that Cobden-Sanderson himself ended up at the bottom of the Thames, entombed in its waters right alongside his beloved type.

Emery Walker outlived his crusty old printing rival, but he spent the last ten years of his life knowing that Cobden-Sanderson had bested him. The Doves Type was gone forever. There was no hope of ever finding it again—unless, of course, you had some kind of Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus.

Cobden-Sanderson ultimately underestimated posterity’s admiration of his font. Over the next century, one devotee of the Doves Type has proved to stand above all others: Robert Green, an English designer who spent three years painstakingly re-creating the type from books printed by the Doves Press. In November 2013, almost one hundred years after it was destroyed, Green released the first publicly available Doves typeface. Since this was the twenty-first century and no one needed punch cutters or metal matrices anymore, Green was able to release it as a digital download for a nominal fee.

In October 2014, while one of the authors of this book sat back daydreaming of finding the Doves Type in the Thames one day, Green went one step further. He hired divers from the Port of London Authority to scour the river for any sign of the lost metal type. Even after a century (and a few Hammersmith Bridge bombings by the IRA), Green’s team succeeded in exhuming 150 individual pieces of the Dove font dumped by Cobden-Sanderson in 1916.

Now we have the Doves Type back (kind of). You can—nay, should—buy a digital re-creation of the complete font for forty pounds online. Doves Type even has its own Twitter feed. As a final act of justice, Green is donating half the recovered Doves font to the Emery Walker Trust. The execution of the original agreement between the Doves partners may have come a century late, but better posthumously late than posthumously never.

The Private Press Movement was a rebellion against the increasing industrialization of printing. It was a revolution fought with ink recipes, and carefully weighted homemade paper, and original typefaces inspired by the first decades of Gutenberg’s press. From that movement emerged a “Visionary and a Fanatic” who would make such dazzling books that one glance is enough to induce goosebumps. Today Doves books are some of the most beloved and sought-after creations of the Private Press Movement. The spirit of that crusade led to a reexamination of every aspect of print. Its innovations spread throughout the printing business, becoming one of the strongest influences on twentieth-century book design.

Over the past century, typography and graphic design have blossomed in ways few could have predicted. But here’s a prediction we’re reasonably sure of: if the 1890s produced its Cobden-Sanderson in reaction to Koenig presses and Linotype machines, it’s safe to assume that the twenty-first century will have numerous Cobden-Sandersons in reaction to the increasing digitization of our times. As long as humans stay human—and by that we mean rebellious visionaries—the spirit of the Private Press Movement will never sink into the dark waters of obscurity.