The Capitol of Rome is dominated by the famous equestrian statue of the emperor Marcus Aurelius. There was originally a defeated enemy under the raised leg of his horse, but even without this prostrate victim, nobody needs to tell us that Marcus Aurelius must have been a very powerful and important man.¹ We understand the statue's message almost instinctively, because this message has been delivered to us so often. In ancient Athens, a horseman (hippeus) was an aristocrat;² in ancient Rome the Equestrians were just below the Senatorial aristocracy.³ Even today, the capital cities of the world are filled with kings and generals on horseback, who do their very best to imitate the imperious gaze of Marcus Aurelius: Henry IV commanding the Seine, a brittle Charles I bewildered by the traffic around him, a very aristocratic George Washington overlooking the undemocratic grandeur of Commonwealth Avenue. These powerful men stare over our heads – we are literally beneath their notice. And this is how we expect things to be. For 3,000 years, the horseman has been a powerful image of the aristocratic gentleman. In German, a gentleman is a ‘rider’ (Ritter); in the Romance languages, he is a ‘horseman’ (caballero, cavaliere, chevalier). To this day, English-speakers describe well-mannered men as ‘horsemanlike’ (chivalrous), and Germans describe them as ‘riderlike’ (ritterlich). So we expect horsemen to be better than us and to rule over us. The ancient Roman statue of Marcus Aurelius is an early example of this image of the ruling horseman, and the countless imitations it has inspired still speak to us.⁴

There is, however, a very different image of horsemen on the same Capitol in Rome. At the very edge of the terrace, overlooking the city of Rome, standing in front of the emperor, are two statues of young men with horses. Most of us tend to ignore them because, even if they loom over us as we climb up the Capitol, they disappear from our field of vision as soon as we reach the top. Michelangelo has ensured that our gaze is instantly drawn to the statue of the emperor by the very design of the Capitol itself. We also dismiss these two sculptures because even though they show men with horses, they are not equestrian statues. These young men are not riding their horses; they are leading them by the reins. We could almost mistake them for servants of the emperor, holding fresh horses for him in case he should decide to change his mount. These young men are, however, vastly superior to the emperor himself. They are the ancient Roman Dioscuri, the young sons of Jupiter himself, the twin horse gods, Castor and Pollux.

The contrast between the equestrian statue of the emperor and the sculptures of the horse gods reveals an ambiguity in our attitude to horses. We are brought up to admire them as symbols of aristocratic power, but we also know that they are farm-animals and require a lot of care. A statue of a ‘great leader’ on horseback might be considered a fine and noble thing, but not too many people would like to work as a stable-boy. We readily understand why cleaning out the stables of Augeias was regarded as one of the impossibly difficult Labours of Hēraklēs.⁵ It is surprising, therefore, to find that the horse gods are ready to perform such a lowly task as looking after their own horses. This surprise is reinforced by the stories told about the horse gods.

There is a nice anecdote from ancient Rome that brings out the contrast between the aristocratic world of the horse rider and the humble world of the horse gods. An ordinary Plebeian called Publius Vatinius was going to Rome, when the horse gods rode up to him and told him that the Romans had won a great victory overseas. Vatinius rushed into the Senate to report the good news, but ‘he was thrown into jail for insulting the majesty and dignity of the Senate with such a silly story’. Later, of course, the Senate had to apologize for its mistake.⁶ This story draws a powerful contrast between the aristocratic arrogance of the senators, who were outraged that this humble citizen would dare to intrude on their meeting, and the friendly behaviour of the horse gods, who thought it perfectly natural that they should deliver their very important message to a very ordinary Roman.

If we are to understand the horse gods, we must lay aside the 3,000-year-old notion that horse riding is for kings. Instead, we must adopt the attitude of the Bronze Age and see it as a very lowly activity, suitable only for cowboys and messengers.⁷ This attitude survived into the historical period of the Greek world, where the Dioskouroi are modest and helpful gods, and are very close to ordinary people. In the Bronze and Early Iron Ages of Vedic India, where they are called the Aśvins, we find that the young horse gods have similar characteristics. They are quick to come to the rescue whenever anyone is in trouble, and they are especially ready to help the old, the weak, the humble. For thousands of years the character of the horse gods remains the same. They distance themselves from the high and mighty, and instead they behave like very helpful messenger boys, who are only too eager to come to the assistance of anyone they may meet, as they wander around the world.⁸ They are the gods of working people; in fact, they are so close to ordinary people that doubts are raised about their status as gods in the myths of India and Greece. They are almost too human.

Why are the horse gods like this? Why are they so helpful to people? Oddly enough, the answer that has often been given to this question is that they are twins. The Indians always referred to them as ‘the two horse gods’ (aśvinau), using the dual form of the noun to emphasize that they were a pair. The Greek story of their birth made it clear that the Dioskouroi were twins. The Romans explicitly referred to the horse gods as ‘the Twins’ (Gemini), and they are still honoured by that name in the night sky. According to many scholars who have written about the horse gods, the mere fact that they are twins explains everything about them.⁹ These scholars believe that there are certain universal features shared by all twins in the mythical and religious views of every culture, so the character and careers of our horse gods are quite predictable from the very fact that they are twins. In effect, they believe that all human beings have reacted to twins in the same way, that this universal fear of twins is ‘the oldest religion in the world’.¹⁰ Their grand theory about twins is known as ‘Dioscurism’.

The most striking thing about Dioscurism is not its content, which consists of extraordinary and implausible generalizations, but rather its general acceptance by the scholarly world. The theory of Dioscurism was developed at the beginning of the twentieth century by the biblical scholar Rendel Harris. His theory was accepted by anthropologists,¹¹ he is quoted with respect by scholars who write on the subject of the horse gods,¹² and his work is still cited with approval in the 2005 edition of the Encylopedia of Religions.¹³ Harris started off by studying Christian legends about twins, and he was particularly fascinated by the Syrian Acts of Thomas, which stated that St Thomas and Christ were twin brothers.¹⁴ They possess what Harris believed to be the essential features of ‘Dioscuric’ twins: they both have the same mother, but one twin is human and the son of a man, whereas the other is divine and the son of a god. Harris rejected this legend as a pagan survival, as an attempt to assimilate Christ and St Thomas with the Dioskouroi.¹⁵ Given the popularity of the Dioskouroi, this was a plausible explanation, but then Harris went on to explore the origin of the divine twins themselves, and in two vast anthropological studies¹⁶ he concluded that they had developed from taboos surrounding real human twins. According to Harris, this fear and worship of human twins was the original religion of the world, and it was the origin of most religious beliefs except his own.¹⁷ He called this religion ‘Dioscurism’, and in this he was followed by his student Krappe, who significantly titled his synopsis of Harris's theories, Mythologie Universelle.¹⁸ Harris ultimately concluded that this great universal rival to Christianity was itself based on a primitive Trinity, which consisted of the Thunder-God and his two ‘Assessors’,¹⁹ the divine twins.²⁰

Harris firmly believed that every tradition relating to twins could be attributed to this worldwide religion of Dioscurism, as is clear from the conclusion to his Cult of the Heavenly Twins:

We have now taken our rapid survey of what may, perhaps, be described as the oldest religion in the world; a religion which is still extant in some of its simplest and most primitive forms, though, of course, it will very soon disappear.²¹

His work also betrays a strong sense of indignation against the practitioners of Dioscurism. Since twin infanticide was practised in some parts of Africa, his crusading zeal against this imaginary religion is understandable, but his tone is invariably mocking and offensive, even when there is no question of infanticide. His followers may not share his indignation or his belief in a single, worldwide Dioscuric religion, but they do accept the idea that there are certain universal practices and attitudes toward twins. In effect, they deny the existence of the ‘oldest religion in the world’ but accept the universality of its beliefs. This is the tragic flaw of Dioscurism, because what Harris and his followers are in fact describing is not a single, universal set of beliefs, but rather an extremely diverse variety of beliefs and practices relating to twins.

Given this variety, it is of course very easy to come up with coincidences between individual practices and beliefs found in one or more societies throughout the world, but these coincidences do not constitute a universal, underlying pattern. Modern anthropologists who study twins have rightly drawn attention to the extraordinary diversity of African beliefs, even ‘among peoples who live side by side’.²² Some scholars have suggested that twin infanticide is not a separate phenomenon from infanticide in general,²³ but the harsh reality is that infant twins (just like infant girls) are regularly put to death or left to die because their desperately impoverished mothers cannot afford to raise them and because they are considered to be a manifestation of supernatural evil.²⁴ There is no such thing as Dioscurism or a single universal approach towards twins; there are hundreds of diverse attitudes, each one peculiar to its own society.

The followers of Harris organized his meandering works into a system. The ethnologist Sternberg in 1916, the folklorist Krappe in 1930, and another folklorist, Ward, in 1968, formulated the general principles of Dioscurism:²⁵

(a) Dual paternity: twins are born when a human mother sleeps with a god and with a man.

(b) Twin tabu: the mother and her twins are banished from society, if not murdered.

(c) Magic powers: twins have superhuman powers, but their divine status is dubious; they use their powers to benefit the human race, they rescue people and promote fertility.

It would be absurd to claim that any of these three beliefs is accepted throughout the world, but it might be worthwhile asking whether they are found in India and Greece. They would, after all, provide us with one way of explaining why the twin gods are so helpful to ordinary human beings, because the three beliefs are interconnected. If one of the twins was human, and if both of them were banished from normal society, they would naturally sympathize with people of low or dubious status who have been abandoned by their fellow men. Harris believed that these principles applied to all twins, human twins as well as twin gods, but we shall find that the ‘primitive’ beliefs of the Indians and Greeks are rather more sophisticated than his own, and that they are quite capable of distinguishing between earthly twins and heavenly ones.

Several pairs of twins are mentioned in the Ṛgveda (RV), but not one of these twins is the child of a human woman, and not one of them has two fathers. The parents of all the gods, Dyaus and Pṛthivī (heaven and earth) are twins (yamiyā, RV 9: 68, 3a); their daughters, Night and Dawn, are also twins (yamiyā, RV 3: 55, 11a). The first human beings, Yama and his sister Yamī, are once again twins (RV 10: 10), and they are the children of the goddess Saraṇyū and the mortal Vivasvant (RV 10: 17, 1c). Both Yama and Yamī are, of course, mortal. Finally, the divine Aśvins are also the twin sons of the same couple (RV 10: 17, 2c). As we shall see later, there are other versions of these stories in which Night and Dawn are sisters but not twins, and where the Aśvins are not even brothers; but the stories I have mentioned make it clear that twins do not require an extra father. In every case the twins are the offspring of one father, and the status of the twins is identical – either both twins are divine or both twins are mortal.

There is, in fact, only one case where two fathers produce children from one mother. The gods Mitra and Varuṇa see the very attractive Apsaras Urvaśī and cannot restrain themselves from ejaculating into a pot. The pot acts as a surrogate womb,²⁶ and from it the two babies Vasiṣṭha and Māna Agastya are born. Urvaśī is their mother because they are ‘born from her mind’ (RV 7: 33, 11b).

They poured their combined semen into the pot;

from the middle of it Māna came up,

from it they say that the ṛṣi Vasiṣṭha was born.

(RV 7: 33, 13b–d)

This story does not conform to the pattern of Dioscurism because all three parents are divine, and Vasiṣṭha and Māna Agastya are the sons both of Mitra and of Varuṇa,²⁷ and surprisingly they are not regarded as twins or even as brothers!²⁸ As far as mythical twins are concerned, one father may beget twins, and two fathers may beget singletons.

When we turn to everyday twins, we find that Harris underestimated the biological knowledge of Vedic Indians. They associated the birth of twins with the problem of the mule. They realized that mules could not reproduce, and that the ability to produce mules was given instead to horses and donkeys. The reproductive power of the mule has, therefore, been distributed among other animals. The male ass is dviretas (‘with double semen’), meaning that he can produce either an ass or a mule.²⁹ The Taittirīya Saṃhitā (TS) (7: 1, 1²) explains it as follows:

He (Prajāpati) followed the mule, took its semen, and placed it in the ass. Therefore the ass has double semen.

The Taittirīya Saṃhitā goes further, however, and declares that mares are also dviretas, since they can produce either a horse or a mule:

He placed it in the mare. Therefore the mare has double semen.

This makes it clear that the word dviretas, in spite of its obvious etymology, is not restricted to males alone and means something like ‘doubly reproductive’. Finally, the Taittirīya Saṃhitā declares that the reproductive capacity (retas, semen) of the mule is also granted to humans (prajāsu), and this is why they can produce twins:

He placed it in humans. Therefore twins are born.

Instead of having the ability to produce one offspring belonging to either of two species, like a mare, human mothers can produce two offspring belonging to the same species. The capacity to produce the additional offspring (a mule or a second child) lies in human nature itself, not in multiplying the number of fathers. Twins are born because of this ‘double reproductive capacity’ (dviretas), not because of double paternity.³⁰

The story of Vivasvant and Saraṇyū reveals that the ability to produce twins rests with the mother alone. When Vivasvant sleeps with her, he begets twins each time (Yama–Yamī and the Aśvins), but when he sleeps with Savarṇā, he has one son only, Manu. So twins have nothing to do with paternity, not to mention double paternity. The same attitude (which happens to be biologically correct) is also found in the medical texts of ancient India. Whether a woman has twins or not depends on the condition of her body, not on the father (or fathers). The action of the breath (vāyu) inside her body determines whether she will give birth to twins or a singleton.³¹

In Greece the situation is similar. The most important twins in the Greek pantheon are Apollōn and Artemis, and they are the children of Zeus and Lētō.³² Both of their parents are divine, and Apollōn and Artemis are gods too. In the Iliad, there are three pairs of men who are explicity called twins (didumoi, or didumaone paide), and in two of these cases Homer specifies that there is one human father alone.³³ In the third case, they are the sons of the god Poseidōn and a mortal woman Molionē, though she is actually married to the human Aktoriōn.³⁴ All three sets of twins are mortal heroes.³⁵ As a final example, the Spartans believed that their unusual dual monarchy was created when the twins Eurusthenēs and Proklēs inherited the throne, but these twins had only one father, Aristodēmos, and one mother, Argeia.³⁶ Since both their parents were human, these kings were human too.

If a god and a human sleep with the same woman, the result will not necessarily be twins. Thēseus, for example, has a human father, Aigeus, the king of Athens, and a divine father, Poseidōn, the god of the sea. Even some historical characters enjoy such double or ambiguous paternity: Alexander the Great had a human father, Philip II, the king of Macedonia, and a divine father, Zeus, the king of the gods. As in India, double paternity is neither necessary nor sufficient for begetting twins.

There are, however, two cases of Dioscurism in the myths of Ancient Greece: the birth of Hēraklēs and his twin brother, and the birth of the Dioskouroi themselves. Both these cases are highly unusual, because normally the offspring of a divine parent and a human parent is a mortal hero, but Hēraklēs and one, if not both, of the Dioskouroi are gods.³⁷

Alkmēnē, the human mother of Hēraklēs, sleeps with Zeus and with her human husband Alkaios on the same night. Hēraklēs is the son of Zeus, the insignificant Iphiklēs is the son of Alkaios. Hēraklēs is unique among the Greek heroes (twins and singletons alike), in that he becomes a god after his death. As Pindar puts it, he is a ‘hero god’ (hērōs theos)³⁸ – quite a contradiction, as far as Greek religion is concerned. Hēraklēs is, therefore, the only Greek mortal who lives on Olumpos, and the only Greek god who is also a ghost.³⁹ His apotheosis is not an original part of his story, because in the Iliad he still appears as a mortal,⁴⁰ and the fact that he is a twin is quite irrelevant to his apotheosis. This development in the cult of Hēraklēs is quite similar to the cult of Asklēpios, who has a divine father and a human mother but is not a twin. Asklēpios is regarded as a hero until the fifth century, and then the Greeks start to worship him as a god of medicine. Even though Hēraklēs was born as one of two twins, this twinship is given very little importance. Homer and Hesiod do not mention his brother,⁴¹ and when Iphiklēs finally appears in the Hesiodic Shield of Hēraklēs (c.600 BC), he plays no role in the adventures of his famous brother.⁴² Hēraklēs may conform to the Dioscuric model, but he is so exceptional a twin that he contradicts the validity of Dioscurism for other Greek twins.

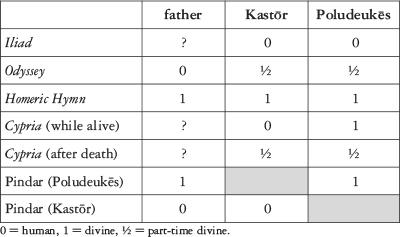

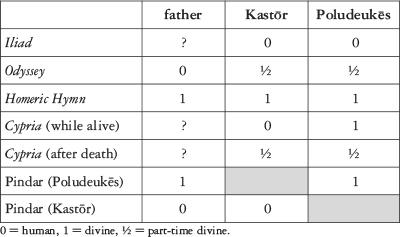

The other case of Dioscurism (the only real one), is that of the Dioskouroi themselves. According to the version of their story that would eventually become the most popular one, Lēdē gives birth to two sets of twins, each set consisting of one mortal and one immortal child. Of her daughters, Helenē was the immortal one, whereas Klutaimnēstra was very mortal indeed and ended up being murdered by her own son; the twin boys of Lēdē, the Dioskouroi, were the divine Poludeukēs and the mortal Kastōr. Some Greeks concluded that Poludeukēs must have been the son of Zeus, and Kastōr the son of Lēdē's earthly husband, Tundareos. This was, however, just one of the stories told about the birth and status of the Dioskouroi. From the earliest period of Greek literature, we find four versions:

In Homer's Iliad, both of the twins are human and quite dead. Their father is not mentioned.⁴³

In Homer's Odyssey, both of them are the sons of the human father Tundareos, and both of them are part-time gods. They spend one day as dead corpses in the earth, and the next day as gods in the earth.⁴⁴ Such a complicated arrangement is unheard of anywhere else in Greek thought.

The early sixth-century Homeric Hymn to the Dioskouroi declares that both of them are the sons of Zeus,⁴⁵ and throughout the hymn regards both of them as gods, as does the contemporary Hesiodic Catalogue of Women.⁴⁶ The Homeric Hymn significantly declares that they receive white sacrificial victims,⁴⁷ which means that they are Olympian gods, not gods of the earth.⁴⁸ Such white victims would not be offered at a tomb.

Finally, the later sixth-century Cypria makes Kastōr human and Poludeukēs divine, but (as in version 2) Zeus grants them part-time immortality.⁴⁹ Pindar later explains this arrangement by giving each of them a different father, and this became the standard version of their story. (For all we know, the Cypria may have provided the same explanation.)

So we have four different ways of describing the Dioskouroi: both twins are fully human; both twins are fully divine; both twins are half-divine; and finally, one twin is human, one twin is divine. The variety of the stories told about their birth and status will, I hope, be clearer from the following chart:

Obviously, the Dioskouroi were regarded as straddling the line between Olympian gods and chthonic heroes, and these stories were various attempts at defining their status. They share this ambiguous status with Asklēpios and Hēraklēs. Due to the great benefits they confer on the human race, the ambiguous Dioskouroi and the mortal Asklēpios and Hēraklēs are worshipped as gods after they die, but they are too human and too earthly to be acknowledged as proper gods while they are still alive.

As a doctor, Asklēpios has to associate with blood, disease and pollution, and this undermines his status as a god. In fact, it even makes him lower in status than the average Greek hero.⁵⁰ The very same objections are raised against the Aśvins in India for precisely the same reasons. Medicine is unsuitable not only for gods but even for Brahmins.⁵¹

Hēraklēs rids the world of monsters and is a great champion of the human race, but he performs these tasks as a slave under the orders of a human king, Eurustheus, and even spent a year living as a woman and working as a slave to a human queen, Omphalē. This miserable existence once again raises questions about his status as a human being, not to mention his divinity.⁵²

Finally, the Dioskouroi are torn between their divine identity as Indo-European horse gods and their human identity as local Spartan heroes, who were simply the mortal sons of the mortal king Tundareos. By playing around with the contrast between sons of Zeus and sons of Tundareos, the Greeks explored the ambiguous divinity of the horse gods.⁵³ Their divinity is ambiguous because looking after horses is a lowly and servile task, unfit for a god or a hero, just as the practice of medicine or performing labours at the behest of another (including, significantly, the task of cleaning out a stable) is unworthy of a god or hero.

No such ambiguous divinity attaches to human twins. Greeks and Indians alike believed that human twins were of human origin alone; even in their myths, Indians never conceived of such a thing as ‘Dioscuric’ twins, and in Greek stories about mythical twins, we only hear of two cases. In the case of Hēraklēs, double paternity is acknowledged but the twinship is ignored; in the case of the Dioskouroi, the twinship is obvious but the paternity and status of the heavenly twins is anything but clear.

The second great principle of Dioscurism is that the twins, and sometimes their mother too, are invariably ostracized from society, if not put to death. In Vedic India, the birth of twins, whether human or animal, was certainly regarded as unusual. In the case of cattle, it is presumed that the mother of twin calves is violent,⁵⁴ and this angry cow is handed over to a Brahmin, whose holiness transforms her dangerous energy into a blessing.⁵⁵ If the wife (or cow!) of a Brahmin bears twins, he must make a special expiatory offering to the gods during the twice-daily gift of milk to the gods, the Agnihotra ritual.⁵⁶ Their birth is an anomaly in the world, but it is listed among a series of mishaps, such as losing a sacrificial implement or eating the wrong food in the middle of a sacrifice. Twins are unusual, but their birth is not an irreparable violation of the natural order, and there is certainly no notion that the twins should be banished or killed.

On the contrary, twins are regarded favourably in the Ṛgveda, and are used as a symbol of equality and harmony. Two offerings of the sacred drink, soma, are described as ‘twin sisters of equal rank’ (RV 10: 13, 2), and another hymn notes with surprise that twins are not always equally strong (RV 10: 117, 9). As we saw, the ancestors of the human race were a twin brother and sister (Yama and Yamī). This was not viewed as a problem until the anonymous poet of RV 10: 10 realized that the human race would thereby derive from an incestuous marriage between a brother and a sister.⁵⁷ The discomfort of the poet arises, of course, from the incest, not from their twinship. Finally, we have the Aśvins themselves, who are worshipped as gods, and have 54 hymns composed in their honour. They do indeed travel around the sky, not because they have been banished, as Zeller suggests,⁵⁸ but because they are saviour gods (nāsatyā), patrolling the heavens and looking for people to rescue, as is explicitly stated in the Ṛgveda.⁵⁹

The Greeks are also quite indifferent to twins. They display no anxiety about the birth of human twins, neither fearing them nor worshipping them. As we have seen, Homer mentions three sets of human twins, two of which are born in the usual way from one mother and one father, and nobody thinks any the less of them for it. The third set is a pair of conjoined twins, the Moliones or Aktoriōnes, whose mother Molionē bore them to her divine lover Poseidōn, even though she had a human husband Aktoriōn. Since Homeric warfare requires close cooperation between the chariot-driver and the warrior, these conjoined twins are actually the perfect team.⁶⁰ The only criticism offered against them is that they have an unfair advantage in chariot-racing!⁶¹ Twins did create a problem in Sparta when the queen Argeia gave birth to two boys, but the Spartans solved it by establishing two royal families.⁶² Obviously there was no tabu against twins, and neither of the boys was banished or prevented from inheriting his father's throne.

Divine twins are not banished either. Lētō was relegated to the island of Delos by Hēra, but she had not given birth to the twins Apollōn and Artemis yet, and Hēra behaved just as badly towards other goddesses and women who slept with her husband. Nor did anyone banish Lēdē or her sons. In fact, the only twins to be outlawed in the Greco-Roman world are Romulus and Remus, and as their myth makes perfectly clear, they are sentenced to death because they threaten the reigning king. The same fate is suffered by many founding heroes (Moses, Cyrus, Jesus Christ) and has nothing to do with twins.

In Greek and Indian myth, the horse gods come to the rescue when people are in trouble. Even in the Ṛgveda itself, the statement that the Aśvins ‘come most readily to misfortune’ is already regarded as an old saying.⁶³ If somebody has been thrown into a pit or into the sea by their enemies and left to die, the Aśvins hear their cry and bring them to safety.⁶⁴ If people are dying of thirst, the Aśvins supply them with something to drink.⁶⁵ They rejuvenate men and find wives for them;⁶⁶ they make sure that women are married and have children.⁶⁷ Finally, they perform all kinds of miraculous cures,⁶⁸ even bringing the dead back to life.⁶⁹ They are the doctors of the gods, and for this reason are treated with some ambiguity by the other gods: the Aśvins are needed because they can heal any defects in a sacrifice, but at the same time the other gods do not want to drink soma with anyone who would practise medicine. As the gods complain, ‘These two are impure; they wander among men and are doctors.’⁷⁰ Medicine was regarded as a polluting profession that was unworthy of a Brahmin,⁷¹ and yet these twin gods condescend to practise it. The Aśvins are almost too nice to the human race, but they still receive the same respect and worship as any other god.

Although the Greek twins had once possessed quite different human characteristics (horse-trainer and boxer), the Dioskouroi in their capacity as gods always act as a pair and are worshipped as a pair. They are especially loved for joining their worshippers at banquets, and for rescuing sailors at sea. During a storm, they appear as lights flashing around the masts, and the sailors know from this miraculous sign that they will be saved from shipwreck by the Dioskouroi. Like all gods, they also help their worshippers to win battles and competitions. The range of their activities is more limited than that of the Indian horse gods, but we see once again the same intimacy with the human race, and the same concern for people in difficulty.

The twin horse gods possess these powers, not because they are twins, but simply because they are gods. Human twins have no special powers and are subjected to no special disabilities or penalties. They are born in the normal human way, and the only ancient work we have in which the mystery of twinship is explored is the comedy of Plautus, The Menaechmus Brothers.⁷² The comedy rests on the fact that nobody can tell the difference between the two twins, not even their nurse or mother,⁷³ which leads to various embarrassing situations. The Ancient Greeks and Indians knew that twins look alike, but they knew nothing of the higher mysteries of Dioscurism. The notion that twins are the product of double paternity, or that they should be ostracized, or that they possess special powers, never entered their mind.

If we turn from the strange fantasies of Dioscurism to the sane and sensible world of Vedic India and Ancient Greece, we discover that although they had not yet discovered the scientific details of childbirth, they knew that one man and one woman could indeed produce twins, and they also knew that some twins were identical, and others were not. Their twin gods were not different in this respect from human twins. The Aśvins are identical twins. In fact, they do not even have separate names, so we do not have to worry which one is which! Both are called Nāsatyas, both are called Aśvins. When they get married they share one wife between them, Sūryā, the daughter of the Sun. In Vedic myth, the Aśvins always act as a pair, as a single unit. In Vedic ritual, they are worshipped first thing in the morning, along with Agni, the god of fire, and Uṣas, the goddess of dawn.⁷⁴ The sacred drink soma is offered to both of the twins from one single cup.⁷⁵ The Aśvins fit in perfectly with Turner's description of twins: ‘what is physically double is structurally single and what is mystically one is empirically two.’⁷⁶

Whereas their Indian counterparts were always called the Aśvins or Nāsatyas as a pair, the Greek horse gods have their own individual names, Kastōr and Poludeukēs; and they have their own special qualifications – Kastōr is a horse-tamer, Poludeukēs is a boxer. In the post-Homeric version of their story, we even find that they were of different status during their lives on earth: Kastōr had been human and mortal, whereas Poludeukēs had always been divine.⁷⁷ Since the Greek twin gods are recognized as separate individuals, they marry one woman each. These women conveniently happen to be twin sisters, which helps to ensure the unity of the brothers while acknowledging their individuality.

The remarkable thing about the horse gods is not that they are twins, but that they are horse gods. To see why this might make them gods of low and questionable status, we shall have to examine the relationship between men and horses in the ancient world.

The long story of horses and humans started on the Eurasian steppes about 6,000 years ago, and it started off rather unpleasantly. Horses were the predominant animals on the great Eurasian plain, which was their natural habitat.⁷⁸ The early people who lived on the steppes hunted wild horses for their meat.⁷⁹ Even today, the Kazakhs, at the eastern end of the steppes, still breed horses mainly for their meat.⁸⁰ The first people to eat horses extensively were the Sredny Stog people (4200–3800 BC), who lived at the western end of the steppes in southern Ukraine.⁸¹ It is not clear, however, whether these horses were domesticated or hunted. Since the Sredny Stog people ate so much horse meat, especially at the village of Dereivka, the American archaeologist, David Anthony, believes that they must have been raising herds of domesticated horses.⁸² By studying the ages at which these horses were killed and eaten, however, the British archaeologist, Marsha Levine, concludes that they were wild horses and that the inhabitants of Dereivka had hunted them.⁸³ Unfortunately, this method has led to dubious results elsewhere,⁸⁴ but we can at least say that there is no undisputed evidence for domesticated horses before the fourth milleninium BC.

The first clear evidence for raising domesticated horses, as distinct from hunting wild horses, comes from Botai (3700–3000 BC), at the eastern end of the steppes in Kazakhstan.⁸⁵ Horses are an important source of meat on the steppes because unlike cows, sheep and goats, they can push snow aside with their hooves and eat the grass underneath, and they can also break through ice to get at the water below. They do not have to be provided with winter fodder. For these reasons, the people living on the steppes had a high incentive to domesticate horses.⁸⁶ It is almost impossible, however, to herd horses unless you are on horseback yourself, and this impossibility has been clearly stated both by Western scholars,⁸⁷ and by Mongolians for whom horse-raising is a way of life.⁸⁸ It is not very surprising, therefore, that the evidence from Botai reveals that the people living there both raised horses and rode them.⁸⁹ The pottery at Botai also shows that they drank mare's milk,⁹⁰ which is clear evidence that these people had domesticated horses.⁹¹ The date of the village of Botai also agrees with the genetic evidence that horses were bred selectively for their colour from about 3000 BC.⁹²

So, sometime around 3500 BC, the people of the steppes raised domesticated horses for meat and milk, and they also rode them. Riding was dangerous and uncomfortable, because although they did have reins with organic bits, they had no saddles⁹³ and no stirrups.⁹⁴ This is the way people rode horses for a long time, and almost 4,000 years later, the emperor Marcus Aurelius is still sitting on a horse blanket without saddle or stirrups. In the fourth millennium BC, there was no question of using horses as draught-animals, since there was no wheeled transport whatsoever until the ox-cart reached the steppes shortly before 3000 BC.⁹⁵ The ox-cart must have started off in a heavily forested region,⁹⁶ but it was used from the Rhine to the Indus by 3000–2500 BC.⁹⁷ These ox-carts had solid wheels made of wood and moved at about 3 km/h.⁹⁸ Meanwhile, the Sumerians of Iraq tried using some other animals to pull these ox-carts. From 2500 BC, we find onagers and donkeys drawing carts and heavy battle wagons.⁹⁹ Interestingly, these animals had been treated like horses up until this time and had been raised only for their meat.¹⁰⁰ The west Asians realized that donkeys were more useful alive than dead, and eventually the people of the steppes and west Asia would discover that horses were also too valuable to eat.

Even after the introduction of the ox-cart, horses could not be used as draught-animals, because until the invention of the stiff collar in the third century AD¹⁰¹ they could not draw a heavy vehicle without choking themselves. So throughout the third millennium BC, there was a division of labour: the ox was used as a draught-animal, the newly domesticated horse was used for riding alone.¹⁰²

The development of horse riding around 3500 BC did not produce any major changes in Bronze Age culture, and almost 3,000 years would pass before its significance for warfare was fully understood. Throughout those centuries, the status of riding was low and it was not practised by the Bronze Age elites. Horses were more or less ignored until the Sintashta culture (2100–1800 BC) of the southern Urals developed a very fast, light-weight vehicle that was specially designed for them: the chariot.¹⁰³

Since Proto-Indo-European predates the twentieth century BC, the late invention of the chariot implies that the Indo-European horse gods must originally have been horse riders, not chariot drivers. The main function of horse riders on the steppes was herding and raiding, so the horse gods were first worshipped by people who visualized them as cowboys herding large numbers of sheep, cattle and horses, or making tribal raids on horseback to seize these animals from their neighbours.¹⁰⁴ Both of these were precarious tasks, and would naturally be assigned to reckless young men, whose lower status matched the lowly art of riding. This is why the youth and lowly status of the horse gods are constantly emphasized in the myths of India and Greece. They are the sons of the sky-god, not independent adult males; they are young and unmarried; they do not deserve to join the soma-drinking gods in India; their divine status is dubious in Greece.

Cowboys and shepherds are always marginal figures in society, and horse riding did not improve their status. To quote an expert on the topic, ‘Although […] a venturesome young man was evidently “able” to ride a galloping horse, the act was both dangerous and uncomfortable’.¹⁰⁵ In India, the socially unacceptable young men known as Vrātyas continued to seek wealth through cattle raids, long after such raids had been abandoned by warlords, and these young men rode horses.¹⁰⁶ When they were on their raids, they imitated the violent behaviour of Rudra and his army; when they came back to the village, the better-behaved Maruts were their role-models.¹⁰⁷ The Maruts themselves are often called ‘young men’ (maryas) in the Ṛgveda,¹⁰⁸ and because of this parallel with the Vrātyas, the Maruts are the only Ṛgvedic gods depicted as horse riders.¹⁰⁹

The first horse riders also served as scouts on the Eurasian steppes, searching for new sources of water and metal.¹¹⁰ These were lonely and time-consuming tasks, but even if they were undervalued in the Bronze Age, they were essential both for maintaining its great wealth in cattle, and for the production of the metals that made this new age possible.

Given the Bronze Age function of riders as scouts, it is perfectly natural that the horse gods would be sent off on search and rescue missions, seeking out people who find themselves endangered in remote places where only the horse gods could find them. Their myth was constantly revised and updated, but the essential character of the horse gods as young scouts and cowboys was firmly established on the Bronze Age steppes and is recognizable behind all their later incarnations.

The horse gods are young cowboys from the Bronze Age, but this age was changed forever by the invention of the chariot. This great innovation took place in the Sintashta culture (2100–1800 BC) of the southern Urals. The essential feature of the chariot was its new light, spoked wheel, which weighed only a tenth of what a solid, disk-wheel of the same size would have weighed. This new feature brought the weight of the entire chariot down to 30 kg,¹¹¹ so it was light enough to be drawn by horses. Their owners were proud of this new invention, so when they died, their horses and chariots were buried along with them.¹¹² These chariot-burials date from the twenty-first century BC.¹¹³ Their chariots were very light vehicles, consisting of a wickerwork body big enough for one man only, and they had light wheels with eight to 12 spokes.¹¹⁴ The chariot-burials reveal that by the twenty-first century BC, the chariot is already regarded as an important status symbol,¹¹⁵ so important that no powerful person would want to leave this earth without one. With this new invention, humans had increased the maximum speed of their vehicles to 30 km/h.¹¹⁶

The impact of this new invention was enormous. It was similar in effect to the invention of the automobile, because it did not just increase the speed at which people travelled; it created an entirely new culture based on the ownership of chariots. The relatively late invention of the chariot also has implications for Indo-European myth and language. Since Hittite already existed as an independent language by the twentieth century BC, Proto-Indo-European must have been spoken before the invention of the chariot. This is why there is no common word for chariot among the Indo-European languages. Instead, they use words like ‘roller’ (Sanskrit ratha), ‘runner’ (Latin currus), ‘framework’ (Greek harma),¹¹⁷ or ‘carrier’ (Mycenaean wokhā, Homeric okhea, German Wagen) to describe this new invention, which did not exist at the time of the original language from which they are all derived.

Since Sanskrit and Avestan have the same word for chariot (Sanskrit ratha, Avestan raθa) and charioteer (Sanskrit rathastha, Avestan raθaešta), Indo-Iranian must still have been one language when the chariot was invented.¹¹⁸ The formulas for building a chariot were already embedded in the Indo-Iranian language, when its illiterate speakers carried this technique with them in their minds¹¹⁹ and put it into practice in the new environments of Iraq (the kingdom of Mitanni), Iran, and India. These formulas would of course have been accompanied by memorized actions, but the verbal formulas themselves were vitally important, as can be seen from the horse-training manual of Kikkuli. When Kikkuli, the horse-trainer from Mitanni, wrote this work in the fourteenth century, he was still using Indic formulas, even though he must have written the work in Hurrian (the language of Mitanni). These Indic formulas were faithfully preserved once again when his work was translated into Hittite.¹²⁰ This memorized, oral art of making chariots and training horses was a rare skill, and the chariot was a luxury good, the prized possession of a great chieftain, on the Eurasian steppes, in Iran, and in India. In west Asia, the chariot became immensely popular and its use spread rapidly throughout the great kingdoms of that region. Its adoption was so rapid that it may in fact have been invented there independently,¹²¹ though the presence of Indic-speaking ‘horse-grooms and horse-trainers’ in Mitanni¹²² and the use of Indic formulas by Kikkuli suggests that these Indic-speaking immigrants influenced, if they did not actually create, the west Asian tradition of building chariots.¹²³

What makes this tradition remarkable is its mass production of chariots. From 1950 to 1850 BC, we find depictions of horses and chariots in Anatolia.¹²⁴ A century later, King Zimri-Lim (1779–1761 BC) of Mari, a Mesopotamian city, had a fleet of chariots,¹²⁵ and by around 1750 BC, one Hittite city alone possessed 40 chariots.¹²⁶ By the sixteenth century, we have evidence that chariots were being used by the Kassite rulers of Babylon,¹²⁷ the kings of Mitanni,¹²⁸ the pharaohs of Egypt,¹²⁹ and the warlords of Mycenean Greece.¹³⁰ Within a few centuries the possession of a vast number of chariots had become obligatory for the great kingdoms of western Asia and for the neighbouring lands of Egypt and Greece. Each of the great kingdoms had 1,000 chariots at its disposal,¹³¹ and a large class of chariot-owners emerged, who were called maryannu in Mitanni, Assyria, and Egypt, a term that some scholars relate to the Sanskrit marya (‘young man’).¹³² These armies of chariots were very expensive to maintain, because in addition to the archer and his chariot-driver, they also required specialists to build and repair the chariot, and to train and look after the horses.¹³³

In spite of its extraordinary popularity, many historians believe that the chariot was of little practical use in warfare. They argue that an archer could not have shot with any accuracy unless the ground was very smooth, and that a mass attack with chariots would have resulted in a disastrous pile of broken chariots and kicking horses.¹³⁴ The main function of the chariot would, therefore, have been to provide an exclusive taxi service to and from the battlefield, where the warrior would fight on foot.¹³⁵ This sceptical notion of the chariot is based on Homer, but he is not a reliable source for the chariot warfare of the Bronze Age, because he lived in an age of footsoldiers armed with spears. Even the older epic tradition, on which he was relying, cannot be trusted, because it originated in northern Greece, where there were no Bronze-Age palaces or chariot-armies. Neither Homer nor his tradition could have imagined a west Asian combat in which two armies of 1,000 archers would charge onto a battle-field in chariots.¹³⁶ In the epic tradition and in Homer's own day, the chariot was ‘nothing more than a prestige vehicle’.¹³⁷ In the Bronze Age, on the other hand, the chariot had been a weapon of mass destruction, and surely no less accurate than the later Parthian technique of shooting from horseback.

Of course, it also served as ‘a vehicle of prestige’¹³⁸ in the Bronze Age, demonstrating to the world that its owner was a member of the international elite of charioteers.¹³⁹ In Vedic India, its possession brought prestige and this was more important than its military function.¹⁴⁰ In Assyria, the possession of a chariot meant that its owner was a member of the warrior nobility,¹⁴¹ and the king was constantly shown hunting from his chariot on the stone reliefs that decorated the walls of his palace.¹⁴² In Israel, when one of David's wicked sons wanted to overthrow him, ‘he procured a chariot and team with fifty guards to run ahead of him’.¹⁴³ In Ancient Egypt, the chariot was used very explicitly to show a man's social status¹⁴⁴ and, as in Sintashta, it was often entombed with its owner.¹⁴⁵ The pharaoh himself was shown in his chariot hunting wild animals or triumphing over his enemies.¹⁴⁶ In Mycenean Greece, the chariot-horse was an ‘aristocratic’ animal, and the chariot itself was used in ‘ceremonial contexts’.¹⁴⁷

Since the chariot was such a powerful symbol of social status, it was inevitable that it would become the only form of transport used by the gods in Vedic India,¹⁴⁸ and that the gods of classical Greece would travel in chariots.¹⁴⁹ Dyēus and the Indo-European horse gods, who had been worshipped long before the invention of chariots, had to get used to this new elitist technology. In India, the Aśvins could not ride, because ‘this was not suitable for a soma-drinking god’.¹⁵⁰ In fact, the Ṛgveda clearly mentions riding only in two hymns. In a hymn celebrating a horse sacrifice, the poet apologizes for any rider who may have hurt the horse with his heels or whip (RV 1: 162, 17).¹⁵¹ The only other reference to horse riders appears in a hymn to the Maruts. The poet clearly regards horse riding as an unsuitable activity for gods or heroes: ‘the heroes spread their thighs, like women giving birth’ (RV 5: 61, 3). Elsewhere in the Ṛgveda, every god, including the Aśvins and the Maruts, is visualized as a chariot driver.

As we have seen, the young Maruts make their appearance as horse riders in book five of the Ṛgveda only because their human counterparts, the impoverished young Vrātyas, were reduced to such disreputable practices as horse riding and small-scale cattle raiding.¹⁵² The Vrātyas preserve the ancient connection between horse riding, cattle raiding, and young men who are not yet socially respectable.¹⁵³ A young Vrātya may have to content himself with horse riding for the time being, but his dream is to have ‘a chariot, a servant (marya), cows, and the love of young women’ (RV 1: 163, 8).¹⁵⁴ Instead of being a young man himself (marya), he will have a young servant (marya) of his own to boss around.¹⁵⁵ When a man acquires a chariot, he is no longer a young, dependent, student, living in his teacher's household; he has become an independent, adult sacrificer with a fireplace and household of his own.¹⁵⁶ Riding is a sign of youth, dependence, and low status. Falk sums up the status of riding in Vedic India in a manner that brings out its association with youth and poverty:

This form of transport was associated with young men who were looked upon as dubious and who had their heavenly counterparts in the Maruts. Every settled householder or sacrificer made sure that he would not lower himself to their social status by riding, even though he had no doubt gone around on horseback himself when he was a young man.¹⁵⁷

Hopkins points out that in the later epics of India, riders still act as mere assistants to the king:

The horse-riders form a sort of aides-de-camp, and are dispatched with messages by the king, not being ordinary cavalrymen, but knights on horseback attending the monarch.¹⁵⁸

In the Hittite Empire, riders likewise served as messengers, and the word pithallu meant both ‘messenger’ and ‘rider’.¹⁵⁹ Tablets from Nuzi (modern Kirkuk) show that in the kingdom of Mitanni (northern Iraq), horse riders acted as ‘messengers, courriers, and scouts’.¹⁶⁰ In Egypt, the main function of riders in wartime was to serve as ‘mounted scouts’,¹⁶¹ and on reliefs commemorating the Battle of Kadesh (1274 BC), horsemen are specifically labelled as ‘scouts’.¹⁶² As elsewhere, riding was considered ‘socially degrading’ for an Egyptian prince.¹⁶³

The same distaste for riding prevailed in Ancient Greece. In the Bronze Age, Mycenaean warriors drove chariots, and depictions of horsemen are very rare.¹⁶⁴ Later, we find that neither the Greek gods nor the Greek heroes permit themselves to ride, and Homer deliberately excludes riding from the narrative of his epics.¹⁶⁵ Riding only appears in two similes, which make it clear that his refusal to mention it elsewhere is deliberate. In Iliad 15: 676–686, Aias is jumping around on the beached ships, and Homer compares him to an acrobat leaping from one horse to another; in Odyssey 5: 371, Odusseus has been shipwrecked and is straddling a piece of wood, just like a rider on a horse. Both the similes have a touch of humour to them, and in each case the hero is in an awkard and slightly ridiculous situation. The mocking tone of these similes demonstrates the low status of riding. There is, however, one instance in which a hero does ride a horse. When Odusseus seizes some Thracian horses, Diomēdēs wants to steal a chariot for them (Iliad 10: 503–506). Athēna appears and tells Diomēdēs to stop wasting time, so he jumps on the horses and rides them back to the Greek ships (Iliad 10: 512–514). The horses have been broken in to accept riders, and the two heroes are perfectly well able to ride.¹⁶⁶ They simply refuse to ride unless they are forced to by desperate circumstances. Homer accurately reflects the understandable preference of Bronze Age warriors for driving a chariot, even though the effective use of horsemen and footsoldiers, and the development of cavalry was making chariot warfare obsolete in Homer's day.¹⁶⁷

A century later, Sappho (late seventh–early sixth century) could say that some people regard an army of horsemen as the finest thing on earth,¹⁶⁸ and the Greeks would eventually be quite happy to depict their heroes on horseback. They never felt comfortable, however, with the idea of gods riding horses. Poseidōn, who produced the first horse, is on a few rare occasions shown on horseback, and the only other exception to this tabu against gods riding is the Dioskouroi, the horse gods themselves.¹⁶⁹ Since the Dioskouroi were not part of the epic tradition,¹⁷⁰ they were never subjected to its rules, which derive from the late Bronze Age. Their image as horse riders was never brought up to date, and was preserved unchanged among later Greeks to whom chariot warfare was unknown.¹⁷¹

The contempt for horse riders was so strong in the Bronze Age that some of it was even directed against the driver of the chariot – he was a disposable servant. In one of the graves where a Sintashta chieftain was buried with his chariot, his driver and horses had been put to death and were buried in a separate chamber above the chieftain's body.¹⁷² The same prejudice lives on in the Mahābhārata, where the Pāṇḍāva warriors refuse to associate with Karṇa, because he is merely the son of a charioteer. The chariot driver was inferior to the warrior, but horse riders were utterly disdained in the new world of chariot owners.

Horse gods who ride seem unusual and too modern in India and Greece, but they are behaving in a perfectly normal way. It is the chariot-driving gods who have changed and been updated. Ironically, the Greeks and the Indians view the radical idea of depicting gods in chariots as a timeless and unchangeable sacred tradition. Nobody dared to challenge this invented tradition later on when chariots became a thing of the past. The young horse gods ride and serve others not because their image is ‘younger’, in the sense of more recent, but because their image dates back to a time when the world was younger.

There is a strong connection between youth, service, and riding horses, a connection that is not restricted to a particular society or language. It merely indicates that the image of these gods was formed in the early Bronze Age, when young men of low status rode horses. There is, however, a closer connection that ties together the horse gods of the Sanskrit, Greek and Baltic traditions. These horse gods are called the ‘descendants of Dyaus’ (Divo napātā) in India, the ‘boys of Zeus’ (Dios kouroi) in Greece, and the ‘sons of Dievs’ (Dieva dēlī) in Latvia. They are, therefore, related to the Indo-European sky-god Dyēus and are Indo-European gods themselves. Even the form of the ritual offerings made to them in Ancient Greece reveals their Indo-European origin.¹⁷³

Before speaking of Indo-European gods, we must specify the meaning of this adjective. ‘Indo-European’ is a term that has been often misused, because it properly refers to languages alone, and should never be used for peoples or cultures. We can speak of ‘Indo-European’ languages, meaning those languages that are derived linguistically from a common ‘Proto-Indo-European’ language. This language may have disappeared before the advent of writing, but its basic vocabulary and grammar have been reconstructed with considerable accuracy by linguists over the past two centuries. We can speak of ‘Indo-European’ metre and poetry, because rhythmic speech is merely a specific form of a language, with its own special syntax and vocabulary.¹⁷⁴ And finally, we can speak of ‘Indo-European’ myths, or more accurately of Indo-European themes, that survive in the later myths of the Indo-European languages. When we learn a language, we do not just learn words and rhythms; we also learn certain formulas that help to describe reality. A formulaic expression found in several ancient languages refers to ‘men and cattle’, making it clear that slaves were regarded as possessions, as human cattle,¹⁷⁵ while the formulaic story of St George and the Dragon goes back to an old Indo-European theme of a hero killing a snake.¹⁷⁶ So there are shared Indo-European vocabularies, grammars, rhythms, and themes, but we cannot speak of the ‘Indo-Europeans’, because there never was such a thing as an ‘Indo-European’ race or culture.¹⁷⁷

The simple mistake of confusing language with race was first made by Friedrich Schlegel in 1808.¹⁷⁸ Schlegel had learned that the various Indo-European languages derive linguistically from a common original language, and he incorrectly concluded that the speakers of these various languages must derive racially from a common Indo-European people. Schlegel gave the fatal name of ‘Aryan’ to this imaginary people in 1819.¹⁷⁹ Schlegel was not a racist himself; he was a German liberal who campaigned for Jewish emancipation (achieved in 1848 after his death), while his wife was the daughter of the German Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn and the aunt of the great romantic composer Felix Mendelssohn.¹⁸⁰ Schlegel based the name of this imaginary race on the Sanskrit word ārya, but this harmless word simply means ‘noble’, and only in the moral and religious sense of the word ‘noble’.¹⁸¹ It was the term used by the Buddha when he spoke of his four noble truths (ārya-satyāni) and the noble path (ārya-mārga) of Buddhism. It does not refer to race, and before the nineteenth century, there was no such thing as an ‘Aryan’ or ‘Indo-European’ people. This people exists only in the paranoid world of race-madness.¹⁸² So if we think of the Aśvins as Indo-European gods, we must not imagine that they have blond hair and blue eyes, or that they speak Sanskrit with a distinctly English or German accent.¹⁸³ It simply implies that horse gods like the Aśvins are found in the myths of several Indo-European languages, and since these myths share enough common features, they must have existed in the story-telling vocabulary of the original Proto-Indo-European language. Just as the words in a sentence will be organized by the rules of Indo-European syntax, so the structure of a story will be based on the themes of Indo-European myth. The ethnic identity of the people who spoke this language and told such stories is both unknowable and irrelevant.

Stories behave more as waves than as particles, and they spread like the bubonic plague rather than like an invading horde of heroes, or a tragic chorus of migrants. We can only observe the waves they cause and the symptoms they produce in a given society; we cannot identify the carriers. If we try to name the carriers, we cease to analyse an ancient myth and start to invent a new myth of our own.¹⁸⁴ This is the source of the great nineteenth-century myth of the Aryan invaders and their wandering tribes. We are left, therefore, with the mobile and moving stories themselves, but that should be quite enough for us; they have managed to entertain people for thousands of years.

If we discover some common Indo-European themes in the story of the horse gods, what can we do with this knowledge? In the nineteenth century, the answer was obvious. The first scholars of Indo-European myths were romantics, and they were frustrated by the reactionary politics of Christianity, by its indifference to the natural environment, and by its repression of human sexuality. They believed that Indo-European myths must have celebrated the wonders of nature,¹⁸⁵ including human sexuality,¹⁸⁶ so they went hunting for the ‘Natural Substrate’ that lay hidden beneath the surface of every myth. Every battle between two heroes, every defeat of a monster by a hero, was really a representation of the conflict between day and night, between summer and winter. Every hero was the sun, every heroine was the moon. Indo-European myths were boiled down until they had all been turned into the same, tasteless mush.¹⁸⁷

The school of Nature Mythology became so distasteful that it led people to abandon comparative mythology throughout the first half of the twentieth century. It was brought back to life by Georges Dumézil, who followed Durkheim in believing that religion is a symbolic way of thinking about society. The mythic themes shared by Indo-European languages belonged to the Proto-Indo-European language, and these themes would therefore be based on the society of the speakers of Proto-Indo-European. This society, he believed, was organized into three classes: the priestly rulers; the warriors; and the producers. Indo-European myths would, therefore, reflect and explain this social structure.

If Schlegel was wrong to argue from a shared family of languages to the existence of an ‘Aryan’ race, it is equally wrong ‘to extend that reality into the social sphere’.¹⁸⁸ Dumézil is arguing from a shared linguistic heritage to a common society.¹⁸⁹ There may be shared myths that show an interest in bishops, knights, and pawns, but we cannot conclude that there was an Indo-European society based on these three classes. In fact, Dumézil's three social functions seem to be based on the three Indian classes, which did not develop until the end of the Ṛgvedic period,¹⁹⁰ and on the three feudal estates, which emerged considerably later. Their absence from Ṛgvedic India, their dubious survival and rapid disappearance in the Greco-Roman world of the farming citizen-soldier, and their abolition in Dumézil's homeland during the summer of 1789, make it quite clear that the three classes are not inherently Indian or European.¹⁹¹

Dumézil's approach is ultimately as reductive as nature mythology, but society is a more interesting topic than the weather, and it does tend to have a greater impact on what we say and do. It would take some effort to show that Cinderella is rather like the moon (unseen by day, brilliant at night), but it is impossible not to notice that there is a bit of a social gap between her and the prince. Fortunately, Dumézil was not reductive by nature, and what makes his work stand out is his love and respect for the unique details of every myth he analyses. Although his three classes were consigned to the dustbin of history in 1789, and do not merit apotheosis in reconstructed myths, it is hard not to admire Dumézil's retelling of the Mahabhārata.¹⁹² It brings clarity to an epic that seems overwhelming and unmanageable, and it inspired the work of Hiltebeitel.¹⁹³ Dumézil's analysis of the early Roman kings is superior to the tedious details of Livy or Dionysius, and he makes these legends sound intelligent and interesting.¹⁹⁴ There was indeed a risk that Dumézil's approach might turn mythology into conservative sociology, but he succeeded in evading it. His love for the imaginative freedom of myth overcame his belief in the rigid structures of its thought, his scholarship overcame his odious politics.¹⁹⁵

Dumézil has indirectly shown us what we could do with Indo-European themes. We can point them out and acknowledge their existence, but the life of myth is based on its variety, and we must always respect the variations more than the theme that lies behind them. Bruce Lincoln's work, Priests, Warriors, and Cattle,¹⁹⁶ provides a model for such an approach, and he represents a third generation of comparative mythologists, by his effective use of anthropology. His comparison between East Africans and Indo-Iranians has disinfected his work from any taint of racism, which has always been a ghost haunting Indo-European studies, ever since its playing-field was invaded by a gang of right-wing hooligans and racist scholars in the late nineteenth century.¹⁹⁷ Lincoln's work explains why Indo-European myths would focus on the cooperation and rivalry between priests and warriors in the endless pursuit of cattle. There is an interesting ideological war being fought between the warrior culture of the Nuer and the priestly traditions of the Dinka, between the warrior-kings of India and the priests who obey no king but Soma, between the violent cattle raiders of Iran and the reformist Zoroastrians, and these culture wars are reflected in their religions and their myths.

Myth cannot, however, be the story of warrior-kings and priests alone. A chess-game may ultimately be decided by the knights and the bishops, and every myth may seem to tell their story,¹⁹⁸ but we must not forget the pawns, because there are always more of them.¹⁹⁹ I would, therefore, like to focus on the cowboys rather than on their sacred and noble employers, and I am encouraged by some ancient poets who did the same thing. The great Iranian god, Ahura Mazdā, may have saved the ox from the meat-eating warrior and placed this animal under the protection of the great priest and prophet Zarathushtra, but the hymns (Gāthās) of the prophet also tell us that the god did not forget the humble men who did the daily work of looking after cattle. When the ox asked the god for help and protection, Ahura Mazdā replied:

The creator shaped you for the herdsman and the pastoralist.²⁰⁰

Homer may have celebrated the epic achievements of warrior-kings and priests, but even though the Muses despise the ‘shepherds living in the fields’ as ‘low-class disgraces, mere bellies’,²⁰¹ they still granted their favours to one of those peasants, Hesiod. They inspired him to denounce the ‘gift-eating kings’ (dōrophagoi basilēs),²⁰² and to celebrate the hard life of the Greek peasant. They transformed him from a poor local poet to a Panhellenic spokesman.²⁰³ We all know and love the wonderful stories told by priests and warriors in which they themselves appear as magicians and heroes, but we must not forget the third estate. These ‘People of No Importance’ have their own stories too, stories about horse-riding gods who take care of them and understand the life they lead.