The horse gods appear for the first time in the earliest Sanskrit work known to us, the hymns of the Ṛgveda. In these hymns, which were composed somewhere between 1500 and 1200 BC, the twin gods are called the Aśvins, which means ‘horse gods’. They are also called the Nāsatyas, which means ‘saviours’,¹ and this is what they are called both in the Ṛgveda itself and also in a document from west Asia, the fourteenth-century Treaty of Mitanni. In this document, the Nāsatyas and the other major Vedic gods (Indra, Mitra, and Varuṇa) are called upon to witness the treaty.² So ‘Nāsatya’ is not just a fanciful or poetic way of referring to the horse gods, it is their official, sacred title no less than the name Aśvins. As Bergaigne remarks, ‘the Aśvins are essentially saviour gods’.³

If we are to judge by the number of hymns addressed to them in the Ṛgveda, the Aśvins must have been very popular gods. The main god of the Vedic Indians is Indra, a heroic and rowdy god; he tops the list with about 250 hymns composed in his honour.⁴ Next come Agni, the god of fire (200 hymns), and Soma, the divine drink of the gods (120 hymns).⁵ This is only natural, because the Vedic Indians honoured the gods by making offerings into a sacred fire, and Agni is both this fire itself and the fire god who transports their offerings to the other gods. Soma is likewise both a god and a real plant, and the greatest sacrifice that can be made to the gods is an offering of soma juice, poured into the sacred fire. After the chief god, Indra, and these two gods who are physically present in the everyday world and act as intermediaries between gods and men, come the Aśvins with 50 hymns.⁶

The Aśvins are very close to human beings and just as helpful as Indra, but in a somewhat quieter way. Indra is the mighty god who kills monsters with his thunderbolt, he is ‘the lord of power’ (śacipati); the Aśvins, in contrast, are ‘the lords of splendour’ (śubaspatī), pleasant, wonder-working gods (dasrā) who help people in trouble. The poet Viśvāmitra celebrates the ‘gentle friendship’ (sakhiyaṃ śivam)⁷ of the Aśvins, and even in his time it was already an ancient tradition that the Aśvins ‘come most readily to deal with misfortune’.⁸ As Bergaigne pointed out a century ago, Indra is warlike, the Aśvins are peaceful; he helps fighters, they help victims; he defeats the enemy, they protect the oppressed; he is an ally, they are saviours.⁹ We shall see later that there is some tension between Indra and the Aśvins; Indra does not quite approve of them, he considers them low-class. But even Indra himself sometimes needs their services, and the friendly Aśvins gently come to his assistance.

From the hymns of the Ṛgveda, one thing is obvious about the Aśvins – they are up and about early in the morning.¹⁰ The priests, of course, are awake before anyone else. They have to get up every morning while it is still dark, and make their offerings to the fire god Agni and the sun god Sūrya. This libation to Agni (the agnihotra) kindles the fire and energizes the sun every day.¹¹ Such a Vedic sunrise is described by a poet of the Vasiṣṭha family in a hymn (RV 7: 67, 2–3) that honours all three morning gods: Agni the fire god, Uṣas the dawn goddess, and the Aśvins.

Agni shines out, lit up by us,

the end of the darkness is seen.

The banner of Uṣas is conspicuous in the east,

made for the splendour of Heaven's daughter.

Now the eloquent Hotar priest, o Aśvins,

honours you with hymns, o Nāsatyas.

Come here to us by many paths,

with your chariot of light and treasure.

A hymn from the Atri family (RV 5: 76, 1) begins in the same way:

Agni lights up the face of Uṣas,

the god-loving voices of the inspired priests rise up.

Come here now on your chariots,

o Aśvins, to the overflowing hot milk (gharma).

In each hymn, we see how the priests bring the sacred fire back to life, the fire god awakens the dawn goddess, and the priests invite the horse gods to enjoy their hymns and join them in a cup of hot milk.

On the main day of a soma sacrifice, the invitation is more elaborate. On this day, the soma stalks will be crushed to make soma juice, and this juice will be offered to the gods. The priests start the day off with a hymn called the Morning Recitation (prātaranuvāka). This long hymn, consisting of selected verses from the Ṛgveda, is recited just before daybreak, and it honours the three morning gods, Agni, Uṣas, and the Aśvins. The priests will crush the soma and honour the other gods only after this Morning Recitation has been performed. If the soma sacrifice is a long overnight ritual (Atirātra), one that lasts throughout the first day and the following night up until the morning after, then the entire sacrifice will end on the second morning with a second recitation to the same gods called the Aśvin Hymn (Aśvinaśastra).¹²

The relationship between the Aśvins and Uṣas is especially close. When the priests sing their chant of praise to her, the Aśvins wake up too (RV 3: 58, 1):

The goddess with the shining chariot brings the bright light.

The chant of praise for Uṣas has awoken the Aśvins.

In one hymn, Uṣas is even asked to wake them up (RV 8: 9, 17):

Wake up the Aśvins, o Uṣas,

up, o great kind goddess.

She goes first, and the Aśvins follow her path (RV 1: 180, 1; RV 1: 183, 2; RV 8: 5, 2). In one case (RV 1: 180, 2), she is even called their sister, which would mean that all three are the children of the sky god, Dyaus.¹³ This family relationship is really just a way of explaining that the Aśvins are morning gods and must therefore be born from the daylight. The real relationship between them is that of colleagues who are up and about early in the morning; Uṣas is ‘the friend of the two Aśvins’ (sakhā aśvinor, RV 4: 52, 2 and 3).

This close connection between the Aśvins and Uṣas led early Indian scholars to make some curious speculations about the true nature of the Aśvins. The first to discuss the Aśvins in some detail was Yaska, who composed his Nirukta (Interpretation) in the fifth century BC. Previous Indian thinkers had separated the twin gods, and since the Aśvins appear at twilight, they had placed each of the gods on either side of the line dividing the powers of light from the powers of darkness.

So what are the Aśvins? Some people say Heaven and Earth. Others say Day and Night. Others say Sun and Moon.

(Nirukta 12, 1)

Nineteenth-century scholars in Europe continued to make such identifications with cosmic phenomena,¹⁴ but some thinkers in Vedic India were more down-to-earth:

The historically-minded say that they were two kings who did good deeds.

(Nirukta 12, 1)

In spite of its secularist reductionism, this Euhemerist view presents us with a more accurate image of the Aśvins. Yaska himself rejects all of his predecessors, both the nature school of mythology and the historical interpretation. Instead, he pursues a structuralist approach, based on his reading of several Vedic hymns. Here are the main stages of his analysis:¹⁵

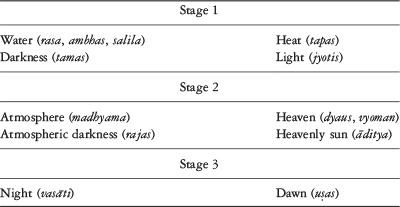

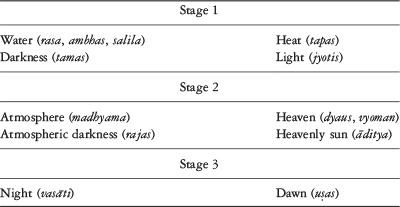

Stage 1: Moist Darkness and Hot Light.

They pervade the universe, one with moisture (raseṇa), the other with light (jyotiṣā).

(Nirukta 12, 1)

Transition from Stage 1 to Stage 2.

The part sharing in darkness (anutamobhāga) is the atmosphere (madhyama), the part sharing in light (jyotirbhāga) is the sun (āditya).

(Nirukta 12, 1)

Stage 2: Dark Atmosphere and Heavenly Sun.

One is the promoter of great strength (sumahato balasyerayitā) and is the atmosphere (madhyama), the other is called the blessed son of heaven (divo ’nyaḥ subhagaḥ putra) and is the sun (āditya).

(Nirukta 12, 3)

Stage 3: Night and Dawn.

One is the son of Night (vāsātya),¹⁶ the other is the son of Dawn (uṣaḥ putra).

(Nirukta 12, 2)

These compressed statements refer to the origin of the universe, and they give the Aśvins a major role in its development.

Rasa usually means juice, but in Yaska's Stage 1, it is a dark cosmic liquid that pervades the entire universe along with hot cosmic light (jyotis). In the transition to Stage 2, Yaska makes it clear that this liquid is identical with darkness, because although the universal light is again called jyotis, he now speaks of the other primal element as darkness (tamas) rather than liquid (rasa). By darkness and liquid, Yaska means the inert dark waters of Not-Being (asat) at the beginning of the world, from which the active bright heat (tapas) of desire emerges to produce Being (sat).¹⁷ For Yaska the Aśvins represent these two primal elements of Moist Darkness and Hot Light.

When Moist Darkness and Hot Light emerge as separate forces, they interact to produce our universe. The Atmosphere (madhyama) emerges from Darkness, the Sun (āditya) emerges from Light.

At this second stage, the visible Atmosphere below (rajas, madhyama) has separated from the invisible Heaven above (dyaus, vyoman). This distinction between Atmosphere and Heaven is so important that when the creation hymn wishes to describe the situation before our universe emerged, it does so in the following way:

There was no Being at that time, there was no Not-Being,

there was no Atmosphere (rajas), there was no Heaven (vyoman) beyond.¹⁸

This separation of the Atmosphere from Heaven marks the real beginning of our universe, but since the Aśvins are going to operate in our part of the universe, Yaska cannot identify them as Dark Atmosphere and Bright Heaven. One Aśvin is equated with the Atmosphere itself (madhyama), but the other cannot be Heaven, he can only be the son of Heaven (divo…putra). He is therefore equated with the Sun (āditya), which is the only part of Heaven that we can actually see.

The third great division of the universe is the distinction between Day and Night, which emerges naturally from the previous division between Dark Atmosphere and Heavenly Sun. Once again, Yaska relates this development to the Aśvins. Each of the Aśvins has a different mother, the sister-goddesses Night (Vasāti) and Dawn (Uṣas), so each Aśvin is identified with the opposite side of this cosmic division through his mother.

The equation of the Atmosphere (Stage 2) with Darkness (Stage 1) and Night (Stage 3) may seem a little strange at first, but it is taken for granted in Vedic thought. In the hymn to the Sun (RV 10: 37), the god turns his bright side (jyotis, light) to the world during the day, but when he turns his dark side to humans during the night, the word used to describe this darkness is rajas, atmosphere.¹⁹ The connection between Moist Darkness, Atmosphere and Night in the middle world is just as natural as the association between Hot Light, Heaven, and Day in the world above.

The fundamental elements of our world are Watery Darkness and Fiery Brightness, Dark Atmosphere and Bright Heaven, Atmospheric Night and Heavenly Day. These elements did not exist originally, they had to be produced, and every morning they have to be recreated by Vedic ritual. When the Aśvins arrive in the morning, they both embody and reproduce these divisions on which the universe is based.

As with most structuralist analyses, this one will be a lot clearer from a chart:

Yaska's interpretation of the Aśvins is brilliant and exciting, because it makes them play a major part in the birth of the universe, but it is an intellectual house of cards, and it is based on very slim evidence. The divisions that he mentions are, of course, vitally important ones in Vedic thought, but in order to equate them with the Aśvins, he must first analyse the twin gods as if they were radically different from each other, and then make a further leap of faith, and identify these contradictory Aśvins with the polar oppositions of Vedic cosmogony. There is little evidence, however, for such a polarization of the Aśvins. The only Vedic passages that separate the two Aśvins are the following:

Born here and there, they are in harmony,

flawless in their body and their names,

one of you is called a victorious patron of Sumakha,

the other is called the fortunate son of Heaven (Dyaus).

(RV 1: 181, 4)

Born separately and flawless,

you have entered a friendship with us.

(RV 5: 73, 4cd)

One is called the son of Night,

the other is the son of Dawn.

(Nirukta 12, 2)

Yaska himself cites the first lines, which come from the Ṛgveda (RV 1: 181, 4 = Nirukta 12, 3), and the last lines, which come from an unknown source. He admits, however, with disarming honesty, that these passages present us with a highly unusual depiction of the Aśvins.

In general, they are praised together, appear at the same time, and perform the same activities.

(Nirukta 12, 2)

Yaska is telling us, in effect, that his wonderful interpretation is based on a very selective use of his sources, and that it distorts the general picture of the Aśvins. Yaska had done his research well, and 25 centuries later, Dumézil, who also hoped to find two opposite horse gods, had to admit that there was no further evidence for such a distinction. He makes this confession with regret: ‘Not only the Vedic hymns, but also the ritual treatises and their commentaries hardly allow us to observe any distinction between the two divine twins.’²⁰

In their discussions of twin gods, Harris and Zeller take the two Ṛgvedic passages cited above as evidence for the ‘Dioscuric’ theory that the Aśvins are the product of one mother and two fathers, and that one of these fathers is divine, the other is human.²¹ Neither of these conclusions is warranted.

Two Fathers. There are indeed two fathers in RV 1: 181, 4; Dyaus is the father of one of the Aśvins, and the other Aśvin has a different father, but the identity of this second father is unclear. The words sumakhasya sūrir would most naturally mean that this Aśvin is ‘a patron of sumakha’. Makha means ‘sacrifice’,²² and ‘patron (sūri) of the good (su) sacrifice (makha)’ would make perfect sense, as would Yaska's paraphrase sumahato balasya īrayitā, ‘promoter of great strength’.

Geldner takes the word ‘son’ (putra) from the next line, applies it to this one too, and translates it as ‘the victorious patron, the son of Sumakha’, but who is Sumakha?²³ Since it means ‘good sacrifice,’ Zeller plausibly identifies him as Vivasvant, the first sacrificer.²⁴ That would help to reconcile this story about the birth of the Aśvins with the more usual story that both of them were the sons of Vivasvant and the goddess Saraṇyū (RV 10: 17).

These lines do not, however, say anything about the mother or mothers of the Aśvins. The mention of Dyaus in the fourth line suggests that the second Aśvin's mother was Uṣas,²⁵ and we have the unidentified line quoted by Yaska (Nirukta 12, 2) to show that when Uṣas is regarded as the mother of one Aśvin, Night is the mother of the other.²⁶ Their parents would therefore be Dyaus and Uṣas for one Aśvin, Vivasvant and Night for the other. So one Aśvin is associated with Dawn and Heaven, the other with Night and Vivasvant, who is usually a mortal in the Ṛgveda, but might here be the later Vivasvant the sun god. We do have two fathers here, but we cannot jump to the conclusion that there is only one mother shared by these two fathers, and this version of the story strongly suggests that the Aśvins are neither twins nor brothers.

One Mother. Harris and Zeller make much of the phrase ‘born here and there’ in the first line of RV 1: 181, 4. This phrase clearly refers to a mother or mothers giving birth in two different places, but Harris wants it to mean something very different and much more complicated. He wants it to say that one mother gives birth in one place to twins begotten by two different fathers. Harris starts by interpreting ‘here and there’ as ‘earth-born and sky-born’. He then reinterprets his own paraphrases to mean ‘child of the sky-god’ and ‘child of an earthly father’.²⁷ Zeller tries to save Dioscurism by translating jātā as ‘begotten’ (erzeugt).²⁸ She argues that we must interpret the phrase iheha jātā in terms of the next lines, and since these lines make it clear that the Aśvins had different fathers, she takes iheha jātā to mean ‘begotten by different fathers’. ‘Begotten’ is not the most obvious way to translate jātā, but even if we accept that it means ‘begotten’ in this line, iheha would mean not that two fathers from different places slept with one mother (Zeller, out of loyalty to Harris, assumes that there can only be one mother), but that the fathers slept with the mothers in two different places.

When we turn to the only other place in the Ṛgveda where the expression iheha jātā is used, we shall discover that it has nothing to do with one mother sleeping with two different fathers. In the Atri family book, we find the following statement: ‘born here and there, they are twin sisters and related’ (RV 5: 47, 5d). The twin sisters here are either Heaven and Earth (Dyāvāpṛthivī), both of whom are regarded as feminine when coupled like this, or Night and Dawn (Naktoṣāsā), who are always regarded as sisters, though not always as twins. Heaven and Earth are the first gods, and obviously could not have had two fathers; Night and Dawn have only one father, Dyaus. ‘Born here and there’ simply means that Heaven and Earth emerged at opposite ends of the world, with the Atmosphere in-between. Night and Dawn belong to different worlds, so that when Dawn appears Night must leave (RV 7: 71, 1). The remainder of the verse states that in spite of being opposites, they are nevertheless twin sisters.

Returning now to the Aśvins, the phrase ‘born here and there’ simply means that for this poet, Agastya, the Aśvins were born into different worlds (the earth and the sky). As a matter of fact, Agastya believes that they are not identical twins. This is an unusual view, as Yaska correctly points out and Zeller acknowledges.²⁹ The remainder of the verse reveals that in spite of being different, the two gods are nevertheless in harmony; they are very good-looking, and both of them have the same name. Significantly, Agastya does not state, as did RV 5: 47, that the gods in question are twins.

Having established that the Aśvins themselves, though a team, are quite different from each other, the poet Agastya then goes on to make the further and more radical claim that the Aśvins have different fathers. Zeller makes the following comment on this claim:

So the Aśvins have two fathers, and can, therefore, be distinguished as a human and a divine partner. This very fact, however, proves their identity as twins beyond a doubt.³⁰

Once again, she is assuming that we have two fathers sleeping with one woman, that one is human and one is divine, and that their children are twins. Everywhere else, the Aśvins are twins, and have one father and one mother. When Agastya gives them two fathers, we cannot automatically assume that he has anticipated Harris by giving the Aśvins two fathers but only one mother. There is no evidence for such a notion in Vedic India, and the archetypal twins, Yama and Yamī (whose names simply mean ‘twin boy’ and ‘twin girl’) have one father and one mother, Vivasvant and Saraṇyū (RV 10: 17, 1–2).³¹

Like Agastya in RV 1: 181, Yaska played with the idea that the Aśvins were not identical twins, but he was too honest to conceal that his elaborate interpretation went against the general picture of the Aśvins presented in the Vedas. It is not, however, his last word on the subject, because he frames his polarizing interpretation of the Aśvins inside a very different view of the gods. Before he embarks on his structuralist analysis, he quotes a stanza that he does not bother discussing, because its meaning is self-evident – ‘it is explained by reciting it’ (Nirukta 12, 2):

You go around in the night,

like two black rams.

When, o you Aśvins,

did you go to the gods?

This stanza, from an unknown Vedic source, assumes that the Aśvins are identical twins. It is as hard to tell the difference between them as it is to distinguish between two black rams in the dark! Right after this statement, Yaska makes the remark we saw above, which once again assumes that they are identical: ‘in general, they are praised together, appear at the same time, and peform the same activities’ (Nirukta 12, 2). Instead of pointlessly trying to differentiate between the two Aśvins, Yaska focuses instead on the very obvious and enormous difference that separates both of them from all the other gods. This is a very significant aspect of the Aśvins in Vedic thought, and will lead to a wide range of speculations in the later interpretations of Vedic ritual. In the Ṛgveda, we learn that the Aśvins were not allowed to join the other soma-drinking gods: ‘the Embryo of Truth (soma) was hidden from the twins’ (RV 9: 68, 5b).

Yaska ends his discussion of the Aśvins with a similar contrast between the Aśvins and the other gods:

The time of these two gods is up until the rising of the sun. At that point, the other gods receive libations.

(Nirukta 12, 5)

Yaska does not develop this thought, but he is aware that the contrast between the Aśvins and the other gods belongs to the mainstream of Vedic thought and ritual, unlike his own subtle attempts to make distinctions between the two Aśvins. This strange gap that separates the Aśvins from the other gods is, as we shall see later, one of their most striking features and posed an intellectual problem that quite literally gave splitting headaches to many scholars in Vedic India.³²

The Aśvins are normally regarded as the twin sons of one mother and one father. In one hymn, their father is Dyaus: they are ‘born of Dyaus’ (RV 4: 43, 3c); in another, their mother is almost certainly Uṣas, though neither she nor they are mentioned by name in this riddle-hymn (brahmodya):

The mother of the twins gave birth to the twins…

… born as a pair, they pursue beauty,

destroying darkness, at the base of the fire (tapus).³³

(RV 3: 39, 3)

The presence of the twins, the destruction of darkness, and the power of the fire leave us with little doubt that the mother mentioned here is the third morning deity, Uṣas. The Aśvins are the children of the incestuous relationship between Dyaus and his daughter Uṣas. On five other occasions, they are referred to as ‘the descendants of Dyaus’ (divo napātā), an ambiguous expression that could mean son or grandson of Dyaus.³⁴ This genealogy from Dyaus and Uṣas is based on the fact that the Aśvins are morning gods, but a different story was to become the standard Vedic version of their birth, and would inspire close analysis in the Brāhmaṇas. This story focuses on the close bond between the Aśvins and the human race, and on the corresponding gap that separates the Aśvins from the other gods. It appears for the first time in the funeral hymn attributed to Devaśravas:

Tvaṣṭar is making a marriage for his daughter!

So every living being comes together there.

The mother of Yama, being married,

the wife of great Vivasvant disappeared.

They hid the immortal woman from the mortals,

and creating a woman of the same type (savarṇā),

they gave her to Vivasvant.

She gave birth to the Aśvins when this happened.

Saraṇyū abandoned her two twin children.

(RV 10: 17, 1–2)

In this hymn, the marriage that Tvaṣṭar is organizing sounds like a svayaṃvara (‘her own choice’), a marriage where suitors assemble and the young woman herself is free to choose her husband.³⁵ The male guests who attend (‘every living being’) may, therefore, be suitors as well as guests. The important point is that these living beings include both gods and men,³⁶ so it is not too surprising when Saraṇyū marries the somewhat mortal Vivasvant. In books 1–9 of the Ṛgveda, he is always regarded as a mortal,³⁷ and he is renowned as the first man to offer sacrifice to the gods, both in the Iranian Avesta and in the Indian Vedas.³⁸

Vivasvant and Saraṇyū get married,³⁹ and she gives birth to Yama, the first man to die and later lord of the dead, and to his twin sister Yamī. At this point, Saraṇyū disappears and abandons her twin children. The hymn only names Yama, but Yamī is included later in the phrase ‘her two twin children’.

We now learn that her disappearance has been planned by the gods, who hide this immortal goddess from ‘the mortals’. This word is in the plural form (martiyebhyaḥ), and it reveals that Vivasvant is regarded as a mortal in this hymn. The plural must refer to three people at least, and since there are no other eligible mortals around apart from Yama and Yamī, it must include Vivasvant as one of them. The gods seem to feel sorry for Saraṇyū, and they decide to rescue her from her unequal marriage. They cannot, however, mistreat Vivasvant either, so they provide him with a ‘woman of the same type’. The word savarṇā is ambiguous,⁴⁰ because it could mean a woman just like Saraṇyū herself, or a woman just like Vivasvant, in other words a mortal being like himself. Vivasvant seems to be quite happy with this consolation prize from the gods, or perhaps she resembles Saraṇyū so closely that he has not even noticed that she is not the same woman.

When Saraṇyū ‘abandons her two twin children’, she is already pregnant with the Aśvins and then gives birth to them among the gods, which probably explains why the Aśvins are divine, unlike their twin siblings. In this hymn, Yama and Yamī are the first human beings, just as Yima is the first man in Iran.⁴¹ This is the Indo-Iranian version of human origins accepted by the newly arrived Vasiṣṭha family (RV 7: 33, 9), but the more usual Indian story traces the human race back to the eponymous Manu.⁴² Naturally, our hymn does not mention Manu, but other passages from the Ṛgveda make it clear that the ṛṣis knew the alternative story that Manu was the son of Vivasvant and his new substitute wife (the savarṇā).⁴³ In this version of the story, the Aśvins would be divine because their mother was the goddess Saraṇyū, and Manu would be a mortal because his mother was a created being, the savarṇā.

The Aśvins are not very important in this Ṛgvedic funeral hymn,⁴⁴ and the main point of these stanzas is to tell us how Yama, the king of the dead, was born from a mortal man and a goddess. This is why his sister Yamī is ignored and the Aśvins are barely mentioned.

Almost a millennium later, the story was retold in greater detail by Yaska in his Nirukta.

A story is told about this. Saraṇyū the daughter of Tvaṣṭar bore a pair of twins (yamau) to Vivasvant the Āditya. She placed another woman of the same type (savarṇām anyām) there instead. Taking on the form of a mare she ran away. Vivasvant the Āditya took on the form of a horse, went after her, and mated with her. From this the Aśvins were born. From the surrogate woman, Manu (was born).

(Nirukta 12, 10)

Yaska's version of the story starts in the usual way with Saraṇyū giving birth to Yama and Yamī, but then it becomes quite different. This time Saraṇyū does not need any help from the other gods. She runs away herself and it is she who creates the substitute wife for Vivasvant. Yaska's phrase ‘another woman of the same type’ makes it clear that the substitute was a woman who looked just like Saraṇyū herself, rather than a woman who was a mortal just like Vivasvant.⁴⁵

This trick is quite enough to conceal her disappearance, but Yaska adds a new episode to the story. He tells us that Saraṇyū turned herself into a mare and then ran away from her family. Vivasvant is deceived neither by the substitute nor by the metamorphosis. He changes into a horse himself, and in this form he mates with her, and she gives birth to the Aśvins. Yaska seems to have used this story about the metamorphosis to explain why her sons are horse gods and bear the name Aśvins. Bloomfield makes the very Ovidian suggestion that Saraṇyū changed into a mare because she could only be satisfied by a stallion!⁴⁶ He believes that the story was taken for granted in the Ṛgvedic hymn: the metamorphosis can be ‘inferred from the designation of her second pair of twins as “the horsemen (açvin)”’.⁴⁷ This is precisely the sort of reasoning followed by Yaska and by the Brahmins, who use this story of her metamorphosis to provide a folk-etymology for the name of the Aśvins. The Greek parallels to this story suggest that it was not invented by Yaska,⁴⁸ and that he was probably drawing on an old myth. This does not mean, however, that we can read Saraṇyū's transformation back into the Ṛgveda, because there is no case of metamorphosis in the Ṛgveda. The Vedic parallels cited by Bloomfield refer to the transformations of Prajāpati and derive from later cosmological speculation.⁴⁹ Prajāpati is barely mentioned, even in book 10 of the Ṛgveda, and nowhere does he appear as a cosmogonic god, except in the very last stanza of RV 10: 121 (which was probably inserted later).⁵⁰ Perhaps the notion of gods in animal-form was regarded as a ‘primitive’ one that had to be excluded from the Ṛgveda.⁵¹ Its late appearance in the Vedic tradition suggests a squeamishness about metamorphosis that Plato would have strongly endorsed.⁵²

Yaska makes a final addition to the story as we saw it in RV 10: 17. He tells us that Manu was the son of Vivasvant and the substitute wife. Here he is once again using an old story, but this time it is one that has been accepted by the Ṛgvedic ṛṣis.⁵³ The story about Manu was omitted from RV 10: 17 only because it was not relevant to a hymn about Yama. In his interpretation of the Ṛgvedic hymn, Yaska is simply drawing on all the old traditional material he can find, but the application of the horse metamorphosis to the story of Saraṇyū is probably his own contribution.

Later again, during the Puranic age,⁵⁴ Śaunaka's Bṛhaddevatā tells the story of Saraṇyū in even greater detail:

6: 162. Tvaṣṭar had twin children,

Saraṇyū along with Triśiras.

He himself gave Saraṇyū

to Vivasvant in marriage.

6: 163. Then Yama and Yamī were born

to Saraṇyū by Vivasvant.

And both of them were also twins,

but the older of them was Yama.

7: 1. Without her husband's knowledge,

Saraṇyū created a woman of the same appearance (sadṛśī);

she entrusted her two children to this woman,

turned herself into a mare, and departed.

7: 2. Not realizing this, Vivasvant

begat Manu in this woman;

he too became a royal sage,

just like Vivasvant in splendour.

7: 3. When, however, Vivasvant became aware

that Saraṇyū had departed in the shape of a mare,

he quickly went after the daughter of Tvaṣṭar,

having turned himself into a horse of the same type (salakṣanaḥ).

7: 4. When Saraṇyū recognized Vivasvant

in the form of a stallion,

she approached him for sexual intercourse,

and he mounted her there.

7: 5. Then in their agitation

the semen fell on the ground,

and the mare sniffed up that semen

in her desire for offspring.

7: 6. Now from the semen which had just been sniffed up,

two young men were born,

Nāsatya and Dasra,

who are renowned as the Aśvins.

(Bṛhaddevatā, 6: 162–7: 6)

Śaunaka closely follows Yaska's version of the story, but he adds some details of his own. The Ṛgveda seems to have regarded Saraṇyū's marriage as a svayaṃvara, but the Bṛhaddevatā makes it quite clear that she did not choose her own husband; Tvaṣṭar married her off to Vivasvant (6: 162).⁵⁵

As in Yaska's version, it is Saraṇyū herself who creates the substitute, but Śaunaka makes it very clear that the substitute looks exactly like Saraṇyū (sadṛśī, 7: 1), that Saraṇyū intends to deceive her husband with this substitute, since she cleverly created it while her husband was not around (7: 1), and that her trick succeeds (7: 2). Śaunaka adds a nice detail in telling us that Saraṇyū entrusted the twins Yama and Yamī to the substitute. Neither the poet Devaśravas nor the scholar Yaska had thought about finding a baby-sitter for the twins. Saraṇyū's trick works so well that Vivasvant has a baby (Manu) with the substitute before he realizes that he has been fooled. In order to produce this effect, Śaunaka must alter the normal birth order. In the Bṛhaddevatā, her children appear in the sequence Yama–Yamī, Manu, and Aśvins, rather than in the traditional order, Yama–Yamī, Aśvins, and Manu, that we saw in the Ṛgveda and Nirukta. Śaunaka also has to present us with the implausible scenario of Saraṇyū wandering around as a mare for over nine months, while the substitute (sadṛśī strī) produces Manu, before Vivasvant decides to pursue her as a stallion.

When they meet again, Śaunaka once again gives agency to Saraṇyū, since it is she who approaches Vivasvant for intercourse. The most extraordinary innovation that Śaunaka makes to her story is the grotesque deatil of her insemination through the nose (7: 5–6). Just as the metamorphosis of Saraṇyū and Vivasvant into horses had been used by Yaska to provide a folk-etymology for the name Aśvins, this new detail was created to explain their other name, Nāsatyas, which Śaunaka must have interpreted as Nose Gods, deriving this name from the word nas, ‘nose’.⁵⁶ As Bergaigne pointed out long ago, Yaska and Śaunaka are drawing on old myths to create new stories of their own that will explain obscure lines in the Ṛgveda.⁵⁷

The story of Saraṇyū raises some doubt about the divinity of the Aśvins. How can the sons of a mortal man and a goddess be real gods? It also emphasises the close relationship between the Aśvins and the human race. They are the sons of Vivasvant, the first man to offer sacrifice; the brothers of Yama, the first man to die, and of his twin sister Yamī; and the half-brothers of Manu, the eponymous ancestor of the human race (manuṣya). As the gods themselves say in the Taittirīya Saṃhitā, ‘These two are impure, they associate with human beings (manuṣyacarau).’⁵⁸

Even though they were originally gods of horse riding, the Aśvins, like all the other gods, drive a chariot, but theirs is unique because it has three wheels and three seats. The third seat is for their shared wife, the Sun Goddess, the Daughter of the Sun (Sūryā, Duhitā Sūryasya). This ménage à trois is such an important characteristic of the Aśvins that a riddle can simply refer to them as ‘the two men who travel by bird with one woman’ (RV 8: 29, 8). No embarrassment is expressed over the sharing of one woman by two men; in fact, the number three is given a favourable, mystical significance. Just as the first two steps of Viṣṇu can be seen by mortals, but his third step goes beyond the visible world and cannot even be seen by birds (RV 1: 155, 5), so two wheels of the chariot in which Sūryā rides with her husbands are visible, but the third wheel requires supernatural insight (RV 10: 85, 16):

O Sūryā, the brahmins (brahmānaḥ) know two of your wheels correctly,

but that one wheel which is hidden, only seers (addhātayaḥ) know it.

The three-wheeled chariot belongs to the Aśvins (‘Aśvins in their three-wheeler’, RV 10: 85, 14ab), but now Sūryā owns it too (‘your wheels, Sūryā’, RV 10: 85, 16a). This hymn does not dwell on her relationship with the Aśvins. It appears only as a brief interlude (RV 10: 85, 14–16), since it interferes with the main theme of the hymn, Sūryā's marriage with Soma. Other hymns describe the beginning of her affair with the Aśvins. It all starts off when she goes away with them in their chariot:

When Sūryā mounted your chariot…

(RV 5: 73, 5a)

The phrase ‘mount a chariot’ (ratham ā-sthā) is a formula for elopement,⁵⁹ so she is not just asking the Aśvins to drive her somewhere. She has decided that she will be a permanent feature of their chariot. We find a variant of the same formula (ratham ā-gam) when the goddess Rodasī decides to run away with the Maruts, and her misbehaviour is explicitly compared with Sūryā's: ‘she mounted the chariot, just like Sūryā’ (RV 1: 167, 5c).⁶⁰ In one hymn that mentions Sūryā's elopement, there is an interesting feminist reversal of the normal formula: ‘the wonderful chariot that the Aśvins mounted (ratham ā-sthā) for Sūryā’ (RV 8: 22, 1).⁶¹ The same reversal is expressed in another hymn (RV 4: 43, 6), where the poet celebrates ‘the journey by which you became the husbands of Sūryā’.⁶² In effect, Sūryā is abducting them, they are mounting the chariot for her.

This irregular sort of elopement, based on mutual desire and aiming at sexual pleasure alone, would later be classified by the law-books as a gāndharva marriage.⁶³ In the Ṛgveda, however, Sūryā is not motivated by any desire to obey law-books. She does as she pleases, and the poet Paura is surely criticizing her irresponsibility when he expresses pity for the winged horses of the Aśvins. Suddenly faced with the unexpected task of transporting the hot and dazzling Daughter of the Sun, the horses have to ‘keep away the heat from burning them’ (pari […] ghrṇā varanta ātapaḥ, RV 5: 73, 5d).⁶⁴ In the Ṛgveda, Sūryā is presented as an independent and impetuous goddess, who is a bad influence on an impressionable young goddess like Rodasī, and if the Aśvins themselves are overjoyed that she has decided to run off with them, their horses find her a little overwhelming. It is not surprising that Sūryā and Rodasī run away with young gods of dubious social status who ride horses, because in Vedic India an independent heiress was quite likely to pursue one of the penniless Vrātyas, who are the human counterparts to the horse-riding Maruts.⁶⁵ At least the Aśvins are respectable enough to possess a chariot, even if it is an unusual three-wheeled chariot.

Sūryā's behaviour would be more socially acceptable if her relationship with the Aśvins had arisen from a proper svayaṃvara marriage, as Geldner and Jamison suggest.⁶⁶ In that case, the Aśvins would have come as formal suitors along with other hopeful men, she would have chosen them as her husbands, and they would be properly and legally married, if it were not for the annoying prohibition of bigamy. A svayaṃvara obliges a woman to choose just one man from among her suitors; unfortunately, she is not allowed to keep all of them, she is not even allowed to keep two of them, not even if they happen to be twins, like the Aśvins.⁶⁷ Sūryā did indeed choose the Aśvins, but she chose to run away with them instead of marrying anyone.

According to Geldner, however, there are some hints in the Ṛgveda that the Aśvins came to the wedding of Soma and Sūryā not as friends of the groom, but as rival suitors for her hand, that there was a general competition with Sūryā as the prize. The main evidence for this is the presence of yet another rival, Pūṣan. Three times in the book of the Bharadvāja family, he is described by the formula kāmena kṛta, ‘overcome by desire’ (RV 6: 49, 8b and RV 6: 58, 3d and 4d). In RV 6: 49, 8b, ‘he is overcome with desire and wins praise (arka)’; in RV 6: 58, 3d, ‘you go on a mission to Sūrya (the sun god), overcome with desire, longing for glory (śravas)’. It is possible that Pūṣan longs for the praise and glory of marrying Sūryā, but when the Ṛgveda speaks of the Aśvins marrying her, they do it for ‘splendour’ or ‘beauty’ (śrī), not for praise (arka) and glory (śravas).⁶⁸ And if Pūṣan were really presenting himself as a suitor for Sūryā's hand, it would be strange to describe this as a ‘mission’ or ‘embassy’ (dūtyā) to her father, because a ‘messenger’ or ‘envoy’ (dūta) always acts on someone else's behalf.

The only place where Pūṣan's desire is clearly directed towards Sūryā herself is in RV 6: 58, 4d, where ‘the gods gave him, overcome with desire, to Sūryā’. This cannot mean that they allowed him to marry her, because no version of her story says so, and this expression would be a very unusual way of describing a marriage, because usually a daughter is ‘given’ to a husband, not the other way round. We can understand this puzzling verse by looking at two other strange statements made about Pūṣan. When the Aśvins run away with Sūryā, we are told that ‘the son Pūṣan chose them as his fathers’ (RV 10: 85, 14d); in another hymn, we are told that Pūṣan is ‘the suitor (didhiṣu) of his mother’ (RV 6: 55, 5a). The term didhiṣu does normally mean ‘suitor’ or ‘husband’, but its literal meaning is ‘wishing to obtain,’ ‘striving after’, and in this case mātur didhiṣu could mean ‘longing for a mother’. Geldner is surely right in concluding that when the gods give Pūṣan to Sūryā, he becomes her son.⁶⁹ This would explain why he chooses and receives the Aśvins as his fathers rather than competing against them as his rivals, and why he longs for and receives Sūryā as his mother, rather than suing for her hand in marriage. Pūṣan wants praise and glory and a mother like Sūryā and a father. He succeeds in all his goals; he even manages to find two fathers. There is no evidence that Pūṣan ever attended a svayaṃvara and presented himself as a future husband for Sūryā.⁷⁰

The same theme of a competition for her hand might also be deduced from the account in the Taittirīya Saṃhitā: ‘you came to the wedding (vahatu) of Sūryā on your three-wheeler, wishing to sit together’ (TS 4: 7, 15⁴). There is nothing unusual about sitting together (saṃsadam) on a chariot, because a chariot always carries a team of warrior and driver working closely together. So there would be no point in mentioning it unless something strange were going on here. The three wheels may reveal an ulterior motive. There will be more than the usual pair ‘sitting together’ on this chariot; it will have an extra stowaway passenger when they go home from the wedding. Whatever ulterior motives the Aśvins may hold, however, they are going to someone else's marriage ceremony, not their own. We find a similar statement in RV 10: 85, 14: ‘you Aśvins came to the wedding (vahatu) of Sūryā on your three-wheeler, asking (for her).’⁷¹ Since they are attending the wedding of Sūryā and Soma, their official role is merely to act as best men or friends of the groom. They may secretly want to wreck the wedding and run away with Soma's bride, but that does not transform her wedding with Soma into a svayaṃvara.

Fortunately, we do not have to speculate about these matters, because Sūryā's wedding is described in great detail in the Marriage Hymn (RV 10: 85).

Soma was the groom (vadhūyur),

the two Aśvins were friends of the groom (varā),

when Savitar gave Sūryā to her husband (patye),

and she approved in her mind.

(RV 10: 85, 9)

Since Savitar gives her in marriage to Soma, this cannot be a svayaṃvara, but luckily for everyone, Sūryā approves of her father's decision.⁷² The Aśvins are described as the varā, which must mean ‘friends of the groom’ here.⁷³ It is too late for them to turn up as rival suitors, since the sun god has already given his daughter to one husband (patye, singular), and Soma is already described as the bridegroom (vadhūyu).⁷⁴ The ceremony proceeds in the proper way, and in the end Sūryā mounts the traditional matrimonial wagon (anas)⁷⁵ and sets off for her new home:

Sūryā mounted the wagon (anas) of the mind,

going to her husband.

The wedding procession of Sūryā proceeded,

Savitar had sent it on its way …

(RV 10: 85, 12–13)

At this point, when it seems that the wedding has come to an end, the Aśvins suddenly intervene and ruin everything for Soma.

… when you two Aśvins came to the wedding of Sūryā

on your three-wheeler, asking for her.

All the gods agreed to it,

and Pūṣan chose you to be his fathers.

When you two lords of splendour came

to choose (vareyam) Sūryā.

(RV 10: 85, 14–15)

This hymn treats the marriage of Sūryā and Soma as the model for everyone to follow, so it is quite shocking that the gods would approve of the outrageous behaviour of the Aśvins. The gods have retroactively recognized the elopement as a legal marriage, just as the law books will one day declare that an elopement is a legitimate gāndharva marriage. We have two very different stories here: a wedding between Soma and Sūryā, and in stanzas 14–16 a polyandrous elopment with the Aśvins. The story of her relationship with the Aśvins was was too well established to be ignored, so it is dutifully inserted into the wedding hymn. It is, of course, completely incompatible with the story of her marriage to Soma, so it has to be ignored throughout the rest of the wedding hymn.⁷⁶

After telling us the story about Sūryā and the Aśvins, the wedding continues as if we had heard nothing. Soma and Sūryā are once again portrayed as a happy couple, and she has decided to make do with one husband alone (patye, singular again in stanza 20 as in stanza 9).

Decorated with Butea flowers, made of cotton-tree wood,

multi-coloured,

golden-coloured, nicely-turning, with good wheels,

mount this place of immortality, Sūryā,

make this a nice wedding for your husband (patye).

(RV 10: 85, 20)

From this point on, the hymn ignores the divine couple. It leaves the paradigmatic marriage of Soma and Sūryā behind, and focuses instead on normal human weddings. When the gods appear again, they play their proper divine roles in a wedding between mortals.

Pūṣan must hold your hand and lead you away from here,

the Aśvins must bring you on their chariot,

go to the house so that you may be its mistress,

as its mistress you may give orders.

(RV 10: 85, 26)

The human bride is identified with her heavenly role-model, Sūryā,⁷⁷ but Pūṣan has no designs on her (neither as a wife nor as a mother), and the Aśvins are well-behaved friends of the groom, who bring the bride to her new home. Soma is still regarded as the model divine husband of every bride. He passes her on to the Gandharva, who in turn passes her on to Agni, who finally hands her over to her human husband (RV 10: 85, 40-41). The Brāhmaṇas likewise regards Soma as the real husband of Sūryā, and the Aśvins merely provide entertainment at the wedding by competing in a chariot-race.⁷⁸ This procedure is typical of the tendency in book 10 to censor ancient myths. The old story of an incestuous union between the twins Yama and Yamī lies behind RV 10: 10, but it is rejected as impossibile; the traditional polyandrous union of Sūryā and the Aśvins makes a sudden appearance in the middle of the marriage hymn, but it is rejected as an impossibility in the rest of the hymn; the wedding goes on as if nothing had happened. The Kuru kings may be happy to include all sorts of ancient hymns and stories in their definitive edition of the Ṛgveda, but book 10 is their own addition and it reflects their concern with order and discipline.

The earlier books of the Ṛgveda do not attempt to reconcile ancient myths with proper ritual behaviour, and they are quite happy to record such stories without censorship. In this less complicated world, the Daughter of the Sun chooses both of the Aśvins because they will make good husbands and good friends:

She came to marry you for friendship,

the noble young woman chose you as her husbands (patī).⁷⁹

(RV 1: 119, 5)

Sūryā is delighted with her choice, which she regards as a personal victory:

The Daughter of the Sun went onto your chariot,

as if reaching the finishing-line first with a race-horse.

All the gods agreed in their hearts.

(RV 1: 116, 17)

The reaction of the gods to her polyandrous relationship is significant. It is the same one we found awkwardly included in the marriage hymn, when the Aśvins eloped with her and the gods granted their approval to the relationship.⁸⁰ Sūryā has made her choice on inscrutable, personal grounds – she likes the look of them⁸¹ – and nobody questions her decision. She does not care too much for traditional marriage; on the contrary, as we saw from the story of Rodasī and the Maruts (RV 1: 167, 5), she is a role-model for other free-thinking goddesses.

We have, therefore, two traditions about Sūryā. In book 10 of the Ṛgveda, she marries Soma to please her father. In the earlier books of the Ṛgveda, she runs off with the the Aśvins to please herself. Her marriage with Soma in book 10 is the only one that is called a marriage (vahatu),⁸² but her elopement with the Aśvins is the only relationship recognized in the rest of the Ṛgveda. The Aśvins are the gods ‘who possess Sūryā as their treasure’ (sūryāvasū, RV 7: 68, 3d), their chariot is ‘the one that carries Sūryā’ (yaḥ sūriyāṃ vahati, RV 4: 44, 1c). It is, in fact, one of their most famous achievements, and it is celebrated in no less than 13 of the 54 hymns dedicated to the Aśvins.⁸³ It is not too surprising that Vedic myth would have brought together a goddess who does as she pleases and two young gods who do not worry too much about the conventions of society. It is anachronistic to view them as rebels, however, because they really belong to a world that preceded the invention of these new traditions. We hear about the radically innovative notion of traditional marriage for the first time in the last book of the Ṛgveda. It is only in this book that we find a rigid form of marriage imposed on all; it is only here that we see the first hints of a class system. The Aśvins and Sūryā belong to an age that was more primitive but enjoyed greater freedom and simplicity.