CHAPTER 4

Put Insight in Focus

The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them in the impossible.

—ARTHUR C. CLARKE

There is a beautiful golf course at the beginning of my long driveway. My lakefront home backs up to the shoreline but fronts the thirteenth tee box. A Jack Nicklaus–designed PGA course, it is the setting for many golf tournaments. While the thirteenth hole is breathtaking—you play 434 yards straight into the lake—it is the fourteenth hole that gets the golfers’ laments in the bar at the end of an arduous eighteen holes.

Almost the entire fourteenth hole is played over the water where the lake shoreline cuts deep into the golf course. Despite the fact that it is a mere 186-yard par-three hole, many a golfer has been psychologically distracted by the giant water trap and had their golf balls land in the water. But the best golfers know a secret—focus only on the hole and don’t get distracted by the fact that your golf ball will be flying over water.

It is a mighty lesson for co-creation partnerships. Insight in focus means the creation of a captivating target at which to aim. But it is more than simply a line of sight for creative energy. It is viewing the target as an emotional pull, thus the added adjective, captivating. That means letting the target serve as a magnetic attraction, not just as a directional intent. Attraction is the reason great missions and visions are often referred to as “a calling”—they summon you to duty rather than just expecting your commitment. Like a Pied Piper of purpose, they compel you to join in.

When I was in infantry officer candidate school at Fort Benning, Georgia, a part of the training was learning to become a sharpshooter with a rifle. A sharpshooter designation is the highest level of marksmanship a soldier could attain; the sharpshooter badge qualified me for sniper school, had I had an interest. My success on the rifle range came from odd advice from the sergeant in charge. “The rifle is not the big player in this activity,” he told me. “It is just you and the target; the rifle works for you both. Be so at one with your target that it pulls the bullet from your rifle barrel. Be so focused on precision that it seems as if the rifle fired itself, leaving you surprised.” Olympic gold medal shooters say championship shooting is an intuitive process, not a mechanical one.

Mutual focus is essential to co-creation partnering. It means there is such a collective focus on the target that you both are surprised when the creative synapses in your brains are fired and an innovative solution emerges. This chapter will outline a series of techniques designed to help pull the ideas from your imaginations. We begin with the outlook or stance needed for effective focus.

In chapter 3 (“Make Customer Inquiry Unleashed and Unfiltered”) we began with a description of panning for gold. A small point in that example was mentioned but not discussed. Here it is again: “Second, you must have a strong faith there is gold in the bottom of this mixture, enabling you to be patient during its extraction.” There are several benefits to faith or belief. It will not only support perseverance, it will help animate your search for focus. Faith is like an agreement you make with yourself that, despite temptations and distractions from other factors, you will remain totally true to the course. It is part of the magical force that pulls the bullet toward the target.

A large hospital in Rochester, Minnesota, held a leadership session on initiating a change management plan to become patient centered. As the session opened, the CEO announced to his leadership team and physician’s council, “Before we can convince our patients we are a patient-centered hospital, we must be ourselves convinced; not just lip service, but ‘I’ll-give-at-least-a-day-a-week-to-make-this-happen’ type involvement.” He reminded them of the difference between the two perspectives by telling the well-worn story of a chicken and a pig viewing a billboard together near their field that proclaimed the upcoming “ham and eggs week.” “If you are as committed as the chicken, we are not ready,” he told his leaders. “We need to be willing to be involved like the pig to make this work.” They elected to wait to start the initiative until they had more “pigs.”

Focus requires seeing the collective target in sharp color, with all around it in blurred black and white.

“Without a dream, you cannot have a dream come true,” wrote the late best-selling author Zig Ziglar. Your goal is to help your customer’s dream come true. But getting the customer’s imagination to be drawn to that dream requires nurturing a passion for it. It means taking the customer’s need and aspiration beyond a ho-hum task to be done and framing it into a deeper, more profound purpose. Remember the bricklayers’ responses to the “What are you men doing” query? Your collective goal is to surface a “cathedral-building” focus rather than a “brick-laying” mindset. And in this important endeavor, a picture is worth a thousand words.

Start with a Picture of Your Customer’s Goal

TravelCenters of America (TA) is the largest full-service travel-center company in the United States, serving professional drivers and motorists alike. My friend John DiJulius, author of The Relationship Economy, and his company, The DiJulius Group, consulted with them on culture change.1 Frontline employees daily deal with countless demanding drivers upset their truck needs repair and worried about truck downtime. To change TA’s culture required altering employees’ mindsets to focus on the “plight of the driver.” The DiJulius Group held brainstorming sessions with TA executives, employees, and most importantly, their customers—truck drivers. They needed a picture-making focus for this co-creation effort. The truck drivers helped them better understand the demands of being away from home for long stretches, fluctuations in demand, fear of layoffs, mechanical issues, and family commitments. Some drivers talked about the guilt they felt from being away and missing their children’s events.

The result? TravelCenters of America created a training video titled A Day in the Life of a Driver. It depicted the typical day of a driver who has not been home for an extended period of time. His goal is to make it home for his son’s basketball game that evening. He has not seen his son play all season. He finds out more drivers with whom he works are being laid off, making him concerned for his job. He finally makes all his stops and is headed home to see his son’s game when one of his tires blows. You realize he probably is not going to see his son’s game. The video shows the driver pulling into a TravelCenters of America truck repair location. The cliff-hanger makes employees eager to say, just like the employee in the video, “I got this one; I got this next driver coming in,” with a determination to get him back on the road and home in time. TravelCenters has repositioned their employees’ mindset to “How can I be a hero today?”

Surfacing the customer’s imagination came through getting truck drivers to characterize their needs and hopes in a very personal manner—the responsibility of being a good parent, the coping with fatigue and distress, and the disappointment of a truck-down situation at a crucial time. It elevated the hope of getting a great customer experience to more than simply fulfilling a basic need. For TravelCenters, learning their customers’ deeper hopes surfaced their frontline yearning to be a hero much like a firefighter saving a child from a burning building. The blending of these hopes became the springboard for the innovative solution they created.

Blend Your Pictures into One

Blending is a synergistic process of mixing different visions into one that is greater than the sum of its parts. It requires listening and valuing, not dominating and winning. It is a collaborative (co-laboring) effort in which all features of competition are removed from the exploration. One approach is for provider and customer to draw a picture of their focus on a flip chart, compare charts, and discuss features of each that can expand, enrich, or enhance its meaning and message. Think of it as an ad campaign you are together pitching to a company or prospect. Consider it as a prototype you are preparing for a design team to turn into a rendering, like a sculpture, picture, or performance.

Blended pictures painted the color of purpose attract imagination and captivate conviction. And they can take many forms. For a meeting between a quick-service coffee chain and a group of their customers, the objective was the creation of a drive-thru that would fit in the corner of a shopping center. There were obstacles to overcome and challenges to address. The meeting started by having company leaders and customers work in separate groups with Legos and Matchbox cars, constructing a mock-up of how a drive-thru could work. They compared constructions and explored similarities. By the end, their focus was clear, but most importantly, it was congruent.

Marriott’s Meeting Imagined website enables meeting planners to go on a Pinterest-type site, create their unique, differentiated meeting, and then work with the onsite meeting staff to implement their design. Again, clarity and congruence of collective visions are vital.

Create a Clear Focus

So, let’s practice with a made-up situation. You are the head of sales for a major hotel. Your primary clients are business groups scheduling meetings at your property. One of your largest clients wants their meetings to be more engaging. The meeting planner schedules a meeting with you and your staff. Here is a framework to organize the focus.

![]() What is your primary goal or aim? Boil it down to a paragraph. Now down to two sentences.

What is your primary goal or aim? Boil it down to a paragraph. Now down to two sentences.

![]() If you elevated your two sentences to be at the “ensure world peace and solve world hunger” level of aspiration, how might it sound?

If you elevated your two sentences to be at the “ensure world peace and solve world hunger” level of aspiration, how might it sound?

![]() What is the end memory you would want your customers to talk about with others? What does it sound like? Create a short one-paragraph script.

What is the end memory you would want your customers to talk about with others? What does it sound like? Create a short one-paragraph script.

![]() If your event were to be nominated for a major award in the future, what would be its top selling points?

If your event were to be nominated for a major award in the future, what would be its top selling points?

![]() What are the top OMGs (oh my goodnesses) you need to avoid and remember?

What are the top OMGs (oh my goodnesses) you need to avoid and remember?

Test Your Focus: Are You Addressing the Right Problem?

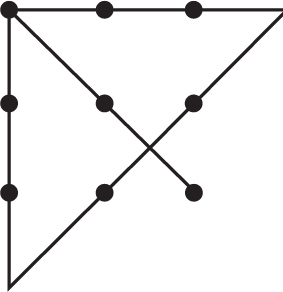

Most adults in the modern world have seen the “connect-the-nine-dots” puzzle (connect all nine dots with four straight lines without lifting the pencil). Its solution requires challenging the made-up, false assumption that you cannot go outside the area of the nine dots. “In challenging assumptions,” wrote Edward de Bono in his classic book, Lateral Thinking, “one must challenge the necessity of boundaries and limits and the validity of individual concepts.”2 Providers, like all humans, can suffer from “functional fixedness”—the tendency to fixate on the way in which a product or service has always been used, making it hard to see an alternative view.

Kimberly-Clark was told by their customers that they didn’t want their toddlers to wear diapers. They also did not want them to wet the bed. It took customers to help Kimberly-Clark break their “functional fixedness” to challenge beliefs and discover the pull-up diaper, not only a breakthrough product, but also a completely new product category.3

What beliefs are the foundation of the customer’s challenge and your innovation goal? Take time to list them and examine closely. Make certain the beliefs are real, not myth. When I was a teenager and my grandfather heard me resist a chore by questioning whether it was doable, he would test that view by asking, “If I gave you a million dollars and a shotgun, could you get it done?” It was amazing how many times “I can’t” turned out to be “I prefer not to.” Assumptions and beliefs are innovation blindfolds you sometimes don’t know you are wearing until they are cross-examined.

View Your Customer’s Need as a Paradigm Shift

Ted Levitt made the point in his book The Marketing Imagination that no one ever bought a quarter-inch drill bit because they collected drill bits for display on the living room wall; they sought a quarter-inch hole.4 Sometimes ideation with customers can lose sight of the hole paradigm and get sidetracked by clinging to a drill-bit paradigm. Be clear about “Why are we here … really?” History is filled with companies that did drill-bit thinking. Large movie companies failed to appreciate that the TV explosion in the 1950s needed content, and watched NBC fill that need. Motels along interstate highways in the 1950s were started by upstarts like Holiday Inn instead of giant hotel companies, who were blinded by a “hotels” paradigm instead of an “away-from-home-lodging” paradigm.

Chick-fil-A is arguably the most loved fast-food restaurant in the country. One of its ads sports the tagline “We didn’t invent the chicken, just the chicken sandwich.” It is the punchline of a partnership backstory that highlights the willingness of Chick-fil-A to think outside the chicken yard. In 1964, a Georgia poultry supplier was hired by an airline to supply them with skinless chicken breasts for the plastic trays of in-flight meals. He ended up with too many chicken breasts that did not comply with the airline’s size requirements. He asked Chick-fil-A founder Truett Cathy if he could use them.5 Cathy could have said, “We sell burgers.” Instead, his company became the largest chicken restaurant in the world.

Think outside the usual paradigm in which your customer’s need resides. Consider whether this focus is a part of something much larger. Strategic questions can help you ensure your focus is relevant and important. Use the ten questions in the sidebar for that assessment.

TEN QUESTIONS FOR ASSESSING FOCUS, CLARITY, AND RELEVANCE

1. Could this problem or issue be better solved if outsourced?

2. Are you and your customer solving the right problem or issue?

3. If the solution you discovered failed to work, who would be harmed?

4. Who would benefit?

5. Might this be your customer’s hobby horse and not the significant challenge your customer is presenting?

6. What would happen if you elected to do nothing, to take a pass?

7. What would be the impact if your organization made this its number one concern?

8. Are you partnering for the right focus?

9. Are you partnering for the right focus but with the wrong partner?

10. What would signal that this problem or issue needed to be automated, eliminated, or exchanged for an alternative?

Put Insight in Focus: The Partnering Crib Notes

Put Insight in Focus: The Partnering Crib Notes

The test of an insight focus is to make certain you are addressing the right problem, issue, or challenge. It is always helpful to ask, Is this the problem or just a symptom? Collective rootcause analysis not only helps zero in on the proper focus, it can ramp up enthusiasm for resolution and ensure joint clarity. The quality tool called Five Whys can help melt away distractions, leaving a raw, unadorned target for disciplined focus. Five Whys is patterned after a child continually asking “why” to any answer to his or her question. The goal is to unearth the root cause. If your customer gets defensive about protecting a sacred, long-held view, avoid elevating defensiveness through challenge. Instead, ask questions that help facilitate a new perspective. Does the focus have a jump-start quality that makes your heart race? Is your customer’s focus compatible with your organization’s vision, values, and capacity?

When Chinese motorcycle maker Loncin wanted to compete effectively against Suzuki, Yamaha, and Honda in the Vietnamese market, their marketing analyses determined their motorcycles were viewed by prospects as too expensive. Established wisdom suggested they talk with customers to find unique ways to add value or perceived value to justify the higher cost. However, rather than turn to customers, Loncin partnered with their suppliers to identify ways to lower manufacturing costs. The hundreds of ideas generated resulted in a 70 percent decrease in costs that translated to a 60 percent increase in market share. Armed with new capabilities, the company expanded into engines and cars.6

Goal setting is similar to traveling from point A to point B within a city. If you clearly understand what the goal is, you will definitely reach the destination because you know its address.

—THOMAS ABREU