The story of the making of The Evil Dead is now very well-known. Two books – Bill Warren’s The Evil Dead Companion (2000) and Bruce Campbell’s If Chins Could Kill (2002) – have recounted the planning, financing and production of the film in detail, and these details have been recounted, time and again, by Sam Raimi, Bruce Campbell and others in interviews and in the DVD commentaries that have accompanied all the versions of the film released since Elite’s Special Edition DVD in 1999. Consequently, my aim here is not to retell a story that has already been told innumerable times, but to focus, specifically, on those factors that fed in to, and laid the groundwork for, The Evil Dead’s distinctive cult reputation.

As Bill Warren notes, the story of the origins and making of The Evil Dead is, above all else, a ‘story of friendships and a business that grew out of having fun’ (2000: 9), and, as I will show, this focus, in all accounts of The Evil Dead’s making, is one of the keys to the film’s specific cult appeal. The story begins with the meeting of a group of teenagers in Wylie E. Groves High School in Birmingham, Michigan between 1972 and 1975. Bruce Campbell, Sam Raimi, Josh Becker, John Cameron, Mike Ditz and Scott Spiegel form a film group and begin to make Super-8 short films on Sunday afternoons in Birmingham. Crucially, their reasons for teaming up relate both to their passionate love of popular cinema (particularly, and famously, their love of the Three Stooges) and, more strategically, to the fact that, between them, they own all the necessary equipment to stage and make their amateur productions.

In 1977, another key member of The Evil Dead crew joins this film collective, when Sam Raimi, now a student at Michigan State University, meets Robert Tapert, a roommate of his brother, Ivan. As Bruce Campbell notes in his book, this occurs at around the same time as their production activities began to move from the realm of fun to their realisation that, actually and potentially, they could ‘make money with these things’ (2002b: 41). This realisation leads to the production of two Super-8 comedy shorts – The Happy Valley Kid (1977) and It’s Murder! (1978). Both films not only mark the growth, as Bruce Campbell notes, of the group’s ambitions and budgets (with the budget of It’s Murder! amounting to over $2,000) but also the growth of their business acumen, with multiple screenings being held at MSU (for $1.50 a ticket for The Happy Valley Kid) accompanied by advertising campaigns (including an elaborate illustrated poster for It’s Murder! produced by The Evil Dead’s make-up and special effects supervisor, Tom Sullivan). This crucial period of filmmaking activity therefore consolidated the approach to film production that would also inform The Evil Dead: combining fun, camaraderie and hard work with a willingness to learn about and address the commercial realities of independent production (budgets, screenings, advertising, box office revenue).

However, alongside this collective process of learning sits the more intimate story of Sam Raimi’s growing relationship with cinema. As recounted by Warren (and Raimi himself), Raimi had fallen in love with the cinema (and with cameras in particular) through watching his father’s home movies, and, crucially, what fascinated him most about these films was the way in which they demonstrated cinema’s effectiveness as a vehicle for illusionism and magic. For Raimi, an amateur magician, his father’s home movies illustrated how, through cameras and editing, time and space could be played with and could create a world of impressive illusions that had the potential to amaze an audience. As Campbell notes, for Raimi, ‘motion pictures were the ultimate sleight of hand’ (2002b: 104), and it was this approach, amongst others, that would, in 1979, inform Raimi, Tapert and Campbell’s decision to move from Super-8 comedy to the horror genre, when planning their first feature film production.

A common misconception, in many journalistic, academic and fan writings on The Evil Dead, is that Sam Raimi is a long-term horror fan. In fact, and as pointed out by Warren, Raimi and company had primarily bonded over their love of slapstick comedy, crime and mystery films from Hollywood’s classical era, and Raimi had, as a youth, always avoided horror, finding it unpleasant and scary. The decision to move towards horror was therefore one informed, primarily, by the group’s growing focus on the economic and commercial aspects of independent production. During screenings of It’s Murder!, the group noted that the only moment that provoked a clear and effective reaction from the audience occurred during a suspense sequence, when a criminal leapt out at a potential victim. As Campbell notes, this consistent response pointed to the fact that a focus on scares and jumps might be the way to go when planning their first feature film, serving as a potential ‘guarantee of provoking a strong reaction from the audience’ (2002b: 65).

This realisation led to a further period of learning and research, illustrating the group’s growing, and partly strategic, interest in cinematic craft and audience response. In early 1979, Tapert, Campbell and Raimi began to frequent drive-in screenings of horror films, keeping a close eye on the sequences that met with approval (or disapproval) from the patrons, and, at the same time, studied and catalogued the plots and budgets of a range of key independent horror productions, most prominently, George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left (1972) and Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974). Through this research, the group realised what Romero had also realised back in the late 1960s: that making a horror film was the most economically viable strategy for a first, independently-made feature film, not only because of its potential to elicit strong audience reactions but also because horror films do not, as a rule, require stars or exotic locations (see Campbell 2002b: 66).

What the horror film also offered, for Raimi, was a vehicle for practising, and learning more about, the cinematic craft of suspense. As Raimi’s knowledge of horror grew, he had begun to realise and appreciate the ‘art’ and ‘craft’ of the suspense created in certain horror films, and the potential impact of this process on the audience (see Warren 2000: 37). As Geoff King has argued, a ‘familiar genre location’ like horror can work, in independent productions, as ‘a stable base – in terms of both form/content and of economics – within which to offer something different’ (2005: 166). It was horror’s ability to work as ‘a stable base’ for both the commercial and creative ambitions of Raimi, Tapert and Campbell (its status as an effective vehicle for commercial success and audience response but also for creativity, learning and experimentation) that would, subsequently, inform the distinctive, ‘different’ tone and character of The Evil Dead.

FINANCING AND PRODUCTION

Aspects of the turbulent story of the making of The Evil Dead mirror the equally famous stories and circumstances that informed the planning and production of George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. As with Romero’s debut feature, the production of The Evil Dead took place in a location with no running water, and was characterised by long shooting days, a skeleton cast and crew who took on multiple roles (both on and off camera) throughout the shoot, and the drafting in of family members and friends to support the production in some way. For J. P. Telotte, these aspects of Night of the Living Dead’s production background ‘suggest just the sort of bricolage that characterises these [type of cult] films, a catch-as-catch-can approach toward production that seems more their rule than an exception’ (1991: 11).

Despite this being identified as a common characteristic of cult films with low budgets, this homemade, ‘catch-as-catch-can approach’ was particularly central to The Evil Dead’s financing and production strategy. Unlike Romero and his associates, who had already formed a production company and produced a number of television commercials and industrial films prior to the production of Night of the Living Dead,2 Tapert, Raimi and Campbell had (outside of a few family friends) no real local business contacts, and had to rely on the goodwill of local investors (snowballing outwards from family and friends, to friends of friends, to cold-calling local companies) to raise enough money to finance the production of their first feature. Prior to this process, in Spring 1979, the group had produced a 32-minute, Super-8 film called Within the Woods at the Tapert family farmhouse, outside Marshall, Michigan, which not only served as a testing ground for Raimi, in terms of trying out and perfecting scary sequences, but which was made explicitly as a ‘prototype’ version of The Evil Dead which could then be screened to potential investors.

After testing out the film through screenings at a local high school and a local cinema, and (inspired by Romero and Hooper) making the decision to film The Evil Dead in 16mm rather than Super-8, Tapert, Raimi and Campbell drew up a contract with Phil Gillis (the Tapert family lawyer), formed their production company, Renaissance Pictures, and then realised that they had only thirty days to raise their target budget of $150,000 (see Campbell 2002b: 84).3 As Ernest Mathijs and Xavier Mendik note, ‘the murky and bizarre legends’ of a film’s origins can ‘help form a basis’ for its subsequent cult reputation (2008: 7), and this is as applicable to the process of financing The Evil Dead as it is to the film’s actual production. The colourful, vivid stories that emerged from this process (screening Within the Woods during a dinner party for a group of dentists, or in the soap aisle of a local supermarket) have been recounted innumerable times, and illustrate the bizarre, incongruous intertwining, throughout The Evil Dead’s production, of the strategic and economic and, through the involvement of relatives, friends and local businesses, the homemade (or home-spun).

By early October 1979, the group had raised enough money from this process ($85,000 of the $150,000 target) to start planning The Evil Dead’s production. After bringing together their skeleton cast and crew (which included a mix of family and old friends, most notably Bruce Campbell’s brother, Don, old school friends, Ellen Sandweiss and Josh Becker and, from Wayne State University, Bruce Campbell’s old teacher, John Mason, plus cameraman Tim Philo and some borrowed Arriflex 16mm cameras), the group headed to a cabin in Morristown, Tennessee, where principal photography began on 14 November 1979. As with the film’s financing, the production of The Evil Dead was gruelling, and full of the kind of colourful and memorable events that contribute to ‘the murky and bizarre legends’ of many cult films. Such events can be seen as an inevitable part of the process of low-budget independent filmmaking in general (with a lack of money and time leading to no sleep and 24-hour shooting stints). However, in the case of The Evil Dead, what seems particularly noteworthy about many of these stories and events was the way that they related to the ambitions and personalities of Raimi, Campbell and Tapert. The most famous product of The Evil Dead’s shoot in Tennessee was the invention of a range of what Campbell calls ‘low-tech but unique camera rigs’ (2002b: 103), which involved the mounting of the camera on 2 by 4 boards: the ‘Shaky Cam’ (used to simulate Steadicam point-of-view shots of the film’s demons), the ‘Ram-o-Cam’ (which enabled Raimi and Philo to achieve the effect of the demonic force smashing through windows) and the ‘Vas-o-Cam’ (which employed gaffer tape and Vaseline in order to simulate dolly shots).4

The creation of these rigs (and of other techniques such as the use of a wheelchair for dolly shots) not only illustrates what many have noted and appreciated about this film – the extent of Raimi and company’s inventiveness and creativity in the face of a restricted budget – but also points to two further qualities that characterised the production of The Evil Dead. Firstly, while these rigs were practical (in that, as Campbell notes, they were cheap and lightweight), their invention and use also illustrate Raimi’s ambitious approach to low-budget horror filmmaking, his desire to create an impact through the production of original and attention-grabbing horror sequences. Consequently, the use of these rigs and techniques, and Raimi’s uncompromising approach to particular shots and sequences,5 were frequently the source of much of the injuries, upset and discomfort experienced by the rest of the cast and crew (not to mention causing eventual damage to Tim Philo’s borrowed Arriflex cameras). As acknowledged by all those involved in the production, it was this painstaking approach that eventually led the production to go way over schedule (from a planned six weeks in Tennessee to twelve weeks), to the majority of the cast and crew having to leave Tennessee before all necessary shooting was completed and, consequently, to the establishment of the film’s other famous production strategy: ‘fake shemping’.

As is now well known, ‘fake shemping’ refers to a practice that had also been employed during the group’s Super-8 filmmaking days, where actors who weren’t available were replaced by others in the crew who doubled for them in certain shots. The flight of much of the cast and crew, five weeks before the end of shooting, led to Raimi, Tapert and Campbell’s reliance on this technique, with Tapert and drafted-in friends, locals and family members (including Tapert’s sister and Raimi’s brother) standing-in for the limbs, heads and torsos of the actors playing Linda, Scotty, Shelley and Cheryl. What this illustrates is that, while any low-budget independent production can produce colourful anecdotes about the gruelling nature of the shoot, it was Raimi’s particular fascination with invention and experimental camerawork that specifically informed a number of the most memorable and distinctive aspects of The Evil Dead’s production story, from Sandweiss bleeding on the plywood affixed to the wheelchair dolly during the filming of her possession in the woods, to Raimi falling asleep behind the camera, to the rewriting of scenes and copious ‘fake shemping’ that occurred in the last weeks of the film’s location shooting.

However, the naming of these camera rigs (the Ram-o-Cam, the Shaky Cam, the Ellie-Vator, the Vas-o-Cam), and of the actor doubling technique (fake shemping), also points to another aspect of the production story of The Evil Dead: the way in which the filming was imbued and informed by the unpretentious jokiness of Raimi, Tapert and Campbell. Indeed, this was not something that began with The Evil Dead. As noted above, ‘fake shemping’ was a strategy that had first been employed by the group during the production of their Super-8 films (and was a term that had originally been coined by Raimi, Campbell and Spiegel, to refer to the standins employed in some of the Three Stooges short films). Furthermore, the terms ‘It’s Murder beams’ and the ‘It’s Murder hand’ referred to the use, during The Evil Dead, of the same Styrofoam beams and rubber hands that had been employed during the making of one of their previous Super-8 productions. As I will go on to demonstrate, the unpretentious jokiness of these three men (and its seeming incongruity when considering the fact that they were making an excessively gory and dark horror film) would continue to play a role in the subsequent reception of The Evil Dead. However, its embodiment in the nicknames given to particular filming techniques also led to the creation of a lexicon of cult terms associated with the film,6 giving the film’s production story a distinctive charm while also contributing to the subsequent ‘proxy’ cult interest (Mathijs & Mendik 2008: 8) in the group’s previous short films.

MARKETING, DISTRIBUTION AND INITIAL RECEPTION

After twelve gruelling weeks, Raimi, Tapert and Campbell returned from Tennessee on 23 January 1980. However, a further year then went by before the film was completed and ready to be screened. During this period, the group obtained loans from banks and investors to shoot the last third of the film, to complete editing and to record the film’s inventive sound effects. In another example of the makers imbuing the film with their own personality, the recording of the sound effects involved Raimi and Campbell’s experimentation with voice effects, faults in the control panel, food, cooking utensils and Three Stooges sound effects recorded directly from the television. Meanwhile, showing a dedication and ambition the equal of Raimi’s, the film’s special effects and make-up technicians, Tom Sullivan and Bart Pierce, were left alone to complete the film’s final ‘meltdown’ sequence, which took over three months due to the time-consuming process of combining stop-motion animation and live-action make-up effects.

Such activities, in the last leg of the film’s production, once again highlight what was, and continues to be, seen as distinctive about The Evil Dead. While the move to horror had been a strategic decision for the Renaissance partners, the creativity and painstaking hard work of Raimi, Sullivan, Pierce, Campbell and Tapert pointed to their desire not just to make money through the use of a tried and tested genre, but to make an impact with their first feature, to make it, in the words of the film’s famous marketing tagline, ‘the ultimate experience in gruelling terror’. As I will go on to show, this desire to create something new, through hard work and experimentation, would be appreciated and recognised by certain journalists and critics. However, despite the planning and hard work of the Renaissance team, The Evil Dead’s distribution and reception trajectory illustrates, quite clearly, how a film’s status as ‘cult’ can be initiated by ‘accidents’ (Mathijs & Mendik 2008: 7) or sheer good luck. It is worth remembering, here, that The Evil Dead was never designed to be what Bruce Kawin would call ‘a programmatic cult film’ (1991: 19). As Raimi has noted, the main aim of the group was just ‘to make a picture that would be effective enough to play in the theatres’ (in Warren 2000: 47), that would allow them to make a mark on the film industry and enable them to pay back those who had invested money in the film. In this respect, while the personality and inventiveness of the film was a product of Renaissance and their distinctive production strategies, the gradual consolidation of The Evil Dead’s status as a cult film was as much the product of those who embraced and responded to it. Furthermore, and as I will highlight, this process was also shaped by a number of changes and shifts that were occurring in film culture at the time of the film’s release, which were completely unanticipated by Raimi and company.

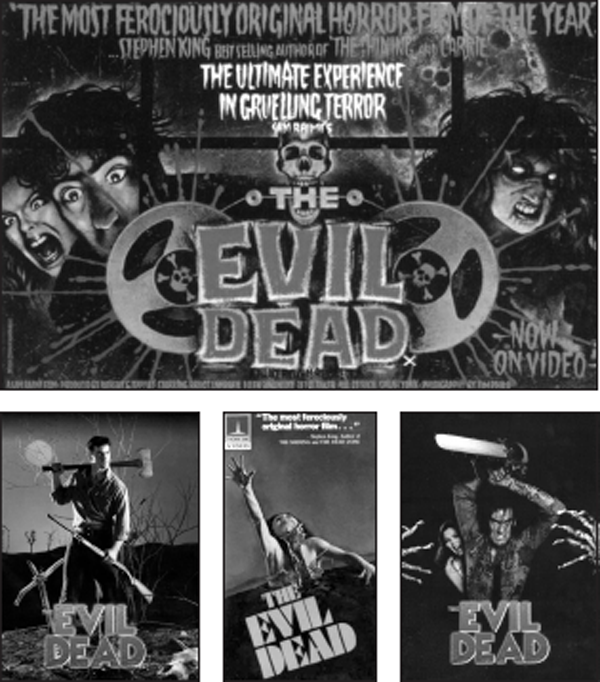

The Renaissance partners’ first piece of luck was to meet three men, between November 1981 and May 1982, who would play key roles in shaping the initial public profile of The Evil Dead. The first was Irvin Shapiro, a highly experienced sales agent, who had handled US distribution deals for a range of foreign-language art films – including Bronenosets Potyomkin (Battleship Potemkin, 1925), La grande illusion (1937) and À bout de souffle (Breathless, 1960) – and a range of independent American horror films, including Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978). On becoming the Renaissance team’s sales agent in November 1981, Shapiro guided them through some key promotional processes and helped them make some crucial decisions. Firstly, after encouraging the group to change the title of the film from The Book of the Dead to The Evil Dead, he oversaw the creation of the film’s US marketing campaign. This included the 1982 photo shoot that spawned the now famous US marketing images for the film, and the production of a trailer edited by Raimi. The trailer, in particular, is extremely effective in conveying what is distinctive about The Evil Dead. What a fan (in an IMDb user review) later referred to as the ‘throbbing personality’ of the film (tomimt, Finland, 20 February 2006) is conveyed here via a montage of images and sounds, culminating in cross-cutting between moving ‘Shaky Cam’ shots and the possessed version of Cheryl moving forward and eventually exploding.

Shots from the climax of The Evil Dead trailer

With these marketing materials in tow (plus a range of other paraphernalia, including homemade matchbooks, t-shirts and badges), the Renaissance team headed to the American Film Market in Los Angeles in March 1982, and it was here that they met the second person who would play an important role in shaping the profile of the film: the young British distributor Stephen Woolley of Palace Pictures. Like Shapiro, Woolley had an interest in both foreign art-house titles and horror films (as evidenced by the range of films screened in his London cinema, the Scala), and what, specifically, grabbed Woolley about The Evil Dead (and would also appeal to some of those who would subsequently review the film) was its effectiveness as a horror film but also ‘as a piece of filmmaking’ which played, self-consciously and inventively, with the properties and capacities of the camera and with sound effects (Woolley 2002). Woolley was also particularly taken with the charming Raimi (who, he felt, could be used to promote the film), and, as a consequence of this encounter, the film’s first sale was to the British market which, subsequently, would lead to a set of Brit-specific meanings becoming attached to and associated with the film.

Shapiro’s second important suggestion was that the group should take the film to the Cannes Film Festival and, subsequently, to the burgeoning fantasy film festival circuit in Europe. As is now well known, it was at Cannes that the group met the final, and perhaps most important, figure in the film’s marketing and distribution story: Stephen King. Like Woolley, what particularly interested King about The Evil Dead was its formal inventiveness, but also the fact that this inventiveness was intrinsically linked to its status as an independent amateur production. For him, the film seemed to epitomise what was valuable and vital about independent filmmaking. As King later explained, while first watching the film at Cannes, he ‘was registering things that I had never seen before in a movie, ever, that were working perfectly. These shots that were like insane Steadicam shots that were going on. Later, Sam told me how they were done, and I thought to myself that it worked because nobody in the organised film establishment would even think about trying it this way’ (in Warren 2000: 89; emphasis in original). It was this response to the film (as well as the fact that, reportedly, it had scared him out of his wits when he viewed it at Cannes)7 that led King to proclaim, in his November 1982 review, that The Evil Dead was ‘the most ferociously original horror film of 1982’ (quoted in Warren 2000: 90), a quotation that would go on to become the most important component of the film’s marketing campaign on both sides of the Atlantic.

Through the guidance of Shapiro, the Renaissance team had met two people whose adoption of The Evil Dead would inform and channel the film’s subsequent, unconventional distribution and reception trajectory. For it was at this point that commercial and critical interest in the film would branch off, in a number of different directions. Firstly, the film was taken up and championed by Bob Martin, editor of the American horror magazine Fangoria, which was emerging, at this point, as a key publication within horror fan circles, due, in large part, to Martin’s decision to focus the magazine around the growing fan interest in special and make-up effects technicians. Martin’s first article on The Evil Dead was published in December 1982 and, firstly, discussed King’s reaction to the film – which suggested that The Evil Dead ‘might be an exception to the usual run of low-budget horror films’ (Martin 1982: 20)8 – and, secondly, featured an interview with the Renaissance partners, which focused on the group’s Super-8 filmmaking history and their experiences when attempting to finance The Evil Dead. However, by the time the second article on the film was published, in June 1983, Martin’s focus had shifted to Tom Sullivan and Bart Pierce and the time-consuming process of producing the film’s special and make-up effects, a strategy that illustrates one way in which the lag between The Evil Dead’s production (in 1979–80) and its initial distribution in Europe, the UK and then the US (in 1982–83) had fortuitous consequences. For, in a stroke of luck unforeseen by the filmmakers, this distribution and reception lag had allowed the film’s foregrounding of special and make-up effects to dovetail, neatly, with the growing interest in this area amongst horror fans.

However, this is to overlook a more unconventional aspect of The Evil Dead’s distribution and reception trajectory. While Fangoria first took an interest in the film in December 1982, the film would not receive a major release in the US until April 1983, after the crucial period (between November 1982 and March 1983) when the film exploded onto the British market, under the careful supervision of Palace Pictures. The film was screened at the London Film Festival in November 1982, and this led to three reviews from the more ‘progressive’ sectors of the British press,9 which were beginning to feature reviews from critics with specialist interest in, and appreciation of, the horror genre (in this case, Kim Newman at Monthly Film Bulletin, Richard Cook at New Musical Express and Julian Petley at Films and Filming). These reviews focused on a number of the film’s qualities that would continue to be foregrounded in some of the subsequent American reviews of the film. Firstly, the lag between the film’s production and British distribution meant that it was here compared favourably to the spate of American slashers – particularly Friday the 13th (1980) – that had already been released in the UK. For Petley and Cook, this meant that the film was valued for displaying more youthful enthusiasm and having more imagination than the ‘manipulative skill’ of ‘the usual trash exploiter’ (Petley 1982: 30; Cook 1982: 45). For Cook, this was partly the result of the film’s ‘audacious’ camera-work, which allowed the film to be appreciated as a purely sensory experience that could provoke spontaneous reactions from viewers. Indeed, the fact that this form of appreciation was built on the earlier comments of Stephen King is illustrated by Petley’s review, where he directly cites King’s famous comment that the camerawork in The Evil Dead makes ‘you want to plaster your hands over your eyes’ and ‘leap up cheering’ (quoted in Petley 1982: 29).

Secondly, the film was also appreciated for something that had not been mentioned by either King or Fangoria (and appears not to have been intended by the filmmakers themselves) but which had been, implicitly, identified by Woolley: the film’s black humour. For Newman and Cook, Raimi’s authorship of the film was not only illustrated through ‘audacious’ camerawork but through an intentional injection of humour which was seen to inform and thus excuse what Newman saw as the film’s ‘deliberately flat dialogue’ (1982: 264). Thirdly, Newman and Petley singled out the film’s ‘meltdown’ sequence for praise, for surpassing equivalent sequences in previous horror films. However, conversely and at the same time, the film was also commended, by all three critics, for its cinephilic references to Jean Cocteau’s Orphée (1950) and to the surrealism of Georges Franju.10

As the film’s reception moved from King’s response to those of the specialist areas of the British press, a reception strand therefore emerged that not only focused on The Evil Dead as a superior horror film but as a film which, through Raimi’s personality, creativity and experimentation, was distinctive and different because it was ‘hard to pin down’ and could be seen to ‘flirt … with the possibility of existing simultaneously as high and low art’ (Hawkins 2000: 28).11 For these critics, the film worked as ‘the ultimate experience in gruelling terror’ because it was a visceral, immediate ‘roller-coaster’ horror experience (Petley 1982: 30). However, in line with Geoff King’s arguments on horror and independent production, its capacity to offer something different (black humour, surrealism and cinematic inventiveness) also allowed it to be appreciated as cinematically and artistically (as well as generically) significant. This conception of The Evil Dead as a multifaceted film that defied easy categorisation would continue to grow, in the American context, when, on the film’s release in the US, the Village Voice noted that the film’s palette and look resembled the work of a ‘demented Renoir’ (Stein 1983: 54) and the Los Angeles Times proclaimed The Evil Dead to be ‘probably the grisliest well-made movie ever’ (Thomas 1983: K4).

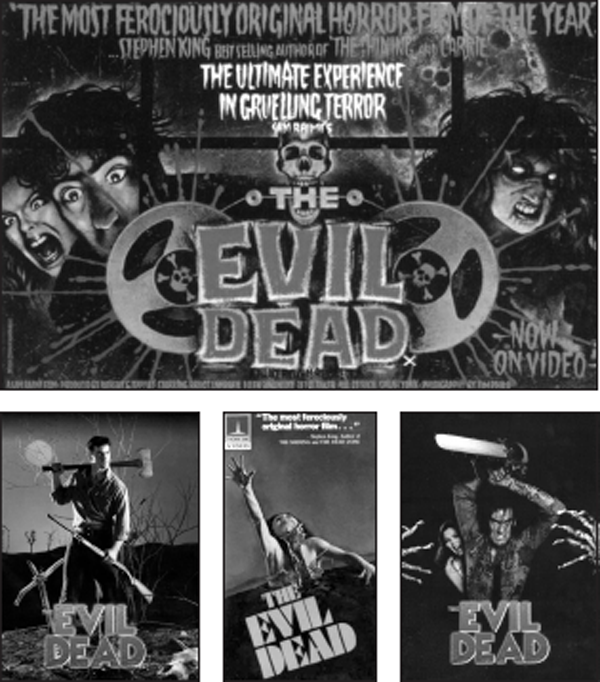

However, aside from initiating this more specialist interest in the film, Palace Pictures, from January 1983, began to promote The Evil Dead, in Bruce Campbell’s words, ‘like it was an A picture’ (2002b: 152). The rationale for this was not only the contemporary interest in horror in general (subsequent to the success of such slasher films as Friday the 13th), but, more specifically, the fact that the horror film was beginning, in the UK, to gain heightened popularity through the new medium of video. As a consequence of this, Palace Pictures made a decision that would further contribute to The Evil Dead’s unconventional distribution history: to release the film, simultaneously, at the cinema and on video. To accompany this release, the company devised a distinctive marketing campaign. Firstly, rather than using the promotional images created by Renaissance and Shapiro, Palace decided to produce their own poster and video cover art for the UK market. Twenty-year-old Graham Humphries was commissioned to design the promotional artwork, and he created a poster and video cover image that has not only become indelibly associated with The Evil Dead in the UK, but which, in many ways, is a more accurate representation of the unique qualities of the film itself.

The original Renaissance marketing campaign seemed to draw on images and ideas from previous horror films. Most prominently, the shot of a girl rising from the grave seems to refer to the iconography of Hammer Horror and to the famous, final sequence of Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976). Furthermore, the images of Bruce Campbell holding a chainsaw aloft and clutching a shotgun and an axe seem to erroneously present his character, Ash, as a conventional, tough-guy hero. While, to a certain extent, this is offset by the use of the Stephen King quote (which emphasises the film’s ferocity and originality), the images themselves fail to foreground what King and other critics had already seen and appreciated in the film – its grainy but vivid look, its inventiveness, its energy. By contrast, Humphries’ illustrations, of a demonic, sickly green-hued Cheryl and a reel-to-reel tape player spurting blood, effectively convey the film’s manic, demented quality and its ‘rough around the edges’ aesthetic (Humphries 2003). As a consequence, Palace Pictures’ marketing images for The Evil Dead proved to be as distinctive as the film itself, and, as acknowledged by British horror critic Alan Jones (2003), the inventiveness of these images can be seen as one of the reasons why the film made such an impact and was so successful in the UK market.

The UK and US marketing images for The Evil Dead

On 17 January 1983 (prior to the film’s simultaneous cinema and video release throughout the rest of the UK), the film opened in cinemas in Scotland. In a canny harnessing of the growing interest in make-up and special effects amongst horror fans, screenings in major cities (in Glasgow, Edinburgh and, subsequently, London) were preceded by live appearances from Raimi and Sullivan, where Sullivan demonstrated some of the special and make-up techniques utilised in the film. However, at the same time as Woolley and his partner, Nik Powell, were priming The Evil Dead for success amongst British horror fans, they were also aware that a growing concern was mounting in the press at the sudden explosion of uncertified horror films onto the video market (leading to the impounding of certain videos under the 1959 Obscene Publications Act and the labelling of these videos as ‘video nasties’).12 Consequently, the focus on the art of special effects and the film’s dark humour, in its initial publicity blitz in the UK, seemed to be a way of reassuring the press and concerned members of the public that, ‘unlike the most recent rash of video nasties, The Evil Dead, despite its heavy reliance on savage gore’, was ‘most definitely a fantasy film of the highest quality’ (Anon. 1983b: 7).

The consequences of these strategies were, ultimately, extremely positive, in terms of The Evil Dead’s long-term cult reputation in the UK. The emphasis, in Palace’s marketing campaign, on arresting marketing images and special gore effects led, on the one hand, to a resounding box-office hit (over £100,000 in box-office takings in the film’s first week of release, subsequently becoming the highest rented video in the UK in 1983). However, on the other hand, Palace’s brash marketing campaign, and the characteristically modest statements made by Raimi in interviews at that time (where he frequently noted that the film was purely designed to make money and to be as horrifying and scary as possible),13 led to disparaging and/or dismissive reviews from the mainstream British press and, ultimately, to the film being seized by the Obscene Publications Squad and branded as ‘the number one nasty’ by moral campaigner Mary Whitehouse (see Dewe Matthews 1994: 242). While, from a commercial perspective, this was bad news for Palace Pictures, the film’s banning, and its association with the ‘video nasties’ moral panic, would subsequently feed into The Evil Dead’s distinctive cult reputation in the UK.

While this dramatic process was playing out in the UK, The Evil Dead was finally released theatrically in the US on 24 April 1983 (in New York) and 26 May 1983 (in Los Angeles). The film was distributed in the US by New Line Cinema and also received its fair share of controversial publicity on this side of the Atlantic, because the film was released without a Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) rating. However, in New York, where the film opened at 72 cinemas, Campbell, Raimi and Tapert had the pleasure of seeing audiences respond to the film in just the way they had intended (jumping at the shocks and scares) as well as witnessing unintended reactions (as audiences laughed at the more implausible responses of the characters to particular screen events). This reception, and the word-of-mouth that resulted, led to long queues outside cinemas and box-office takings of $685,000 in the film’s first week of release.

In comparison to this, the film’s Los Angeles release was, as Bill Warren notes, ‘disappointing’ (2000: 97), with the film opening at only 15 cinemas and pulling in $108,000. As Bruce Campbell notes, in If Chins Could Kill, The Evil Dead ‘ had taken four years to make, but its theatrical run was only a couple of months – too short to get any sense of success’ (2002b: 154). What the Renaissance partners were yet to realise, however, was that The Evil Dead’s reputation would continue to be shaped and determined by factors that they could not have foreseen in 1979, when they set out to Tennessee to make a film that they thought would succeed, primarily, in the then still relatively buoyant American drive-in market. The film would become a cult classic, but its cult reputation, in the US, UK and elsewhere, would be achieved primarily not through drive-in screenings or repeated shows in New York theatres but through its status as a milestone video horror hit. As Matt Hills has argued, ‘what can and has been counted as “cult” film has far exceeded the phenomena of midnight movies’ (2007: 449), and, as the next chapter will illustrate, the cult afterlife of The Evil Dead serves as a vivid illustration of this.