From its initial release in 1983 to its US video re-release in 1998, The Evil Dead’s reputation as a legendary cult video title, and a landmark independent horror film, slowly grew. The release, in 1987, of the film’s higher-budget sequel, Evil Dead II: Dead by Dawn, provided journalists and reviewers with an opportunity to reflect back on the distinctiveness and significance of the original film. In a series of on-set reports on the making of the sequel in Fangoria, The Evil Dead was termed ‘a legendary gore flick’ and ‘a genuine, audience-certified cult classic’ (Murray 1987: 27; O’Malley 1987: 34), illustrating how quickly the cult label became attached to the film. Then, in 1988, Jonathan Ross’s classic cult television series, The Incredibly Strange Filmshow used the UK release of Evil Dead II as a means of highlighting and exploring the significance of the original film. As with the 1982 Fangoria article on the film, Ross’s interviews with Raimi, Campbell and Tapert drew attention to the unique aspects of the film’s production history: the unusual and anecdote-filled financing process, the filmmakers’ Super-8 filmmaking history, the production of Within the Woods, the group’s love of the Three Stooges, and the invention and use of the ‘Shaky Cam’ and other camera rigs in The Evil Dead and its sequel.

In his ‘Cultographies’ volume on Peter Jackson’s Bad Taste (1987), Jim Barratt focuses on the importance of ‘making of stories’ to the reputation-building that occurs around particular cult films. As he argues, ‘the elements given prominence’ in such making of stories, as they continue to circulate in the years after the film’s release, tend to be ‘those most likely to foster cult interest in the film … emphasising its marginal status (ultra low budget, initiated by industry outsiders)’ and ‘valorising its achievement in the face of adversity (funding set backs, cast departures)’ (2008: 27). Ross’s interviews with the Renaissance partners (which perpetuated the focus on those aspects of The Evil Dead’s production which were most unusual and memorable) seem to have played a key role in this reputation-building process, particularly in the British context. These interviews are available on YouTube, and were included as a DVD extra on Anchor Bay UK’s 2003 Evil Dead trilogy DVD box set.

However, in the context of 1988, what was noteworthy about these interviews was not only that they served to further consolidate the legendary status of those elements that were deemed most important to the film’s making of story, but also the fact that this renewed interest in the film’s unique cult qualities was supported by the lack of availability of the film (at this time) in the UK. The ‘video nasties’ scandal and the establishment of the Video Recordings Act (VRA) in the UK in 1984 had led to The Evil Dead being ‘quietly refused a certificate’ by the British Board of Film Classification in 1985 (Kermode 2001: 12), when Palace re-submitted the film for video classification (with separate video classification now being a mandatory requirement after the VRA). For the next 17 years (up to the release of Anchor Bay’s uncut DVD version in 2001), the original UK video version of the film was thus not legally available in Britain, leading to The Evil Dead becoming a much sought-out property (in ex-rental or bootleg form) on the video black market that developed subsequent to the VRA. The situation was similar in the US. As Michael Felsher notes, the film had been ‘a rental smash’ in the US on its initial release on video, as teenagers started spreading the news about the ‘ultimate experience in gruelling terror’ amongst their friends (2002: 8). However, in the early 1990s, the US version of the video went out of print. As Felsher notes, the early 1990s was therefore ‘the worst time to be an Evil Dead fan. The available video copies were drying up … Fans were desperate for a fix, and would do anything to own the film’ (2002: 10–11).

What the Ross interviews illustrate is the way in which The Evil Dead’s cult reputation, from the period of its initial theatrical and video release up until 1998, was built and perpetuated through the contrast between the availability of facts and stories about the film, and the film’s unavailability in the video format through which its greatest success and impact had been achieved. Luckily, as interest and fascination in the original Evil Dead film grew, two new mediums emerged, with both serving to organise and propel this cult interest. Firstly, in 1997, Ash’s Evil Dead Page (later to become the largest Evil Dead fan website Deadites Online), was established, followed, in 1999, by its British counterpart, Within the Woods. Secondly, and perhaps most crucially, 1998 saw the first re-releases, on home video, of the uncut version of The Evil Dead, followed, in 1999, by the first of many DVD special editions of the film.

As Barbara Klinger has argued, ‘through the often extensive background materials that accompany it, a special edition appears to furnish the authenticity and history so important to establishing the value of an archival object’ (2001: 138). This chapter will consider how these special editions, as well as Internet fan activity, DVD reviews and retrospective articles on The Evil Dead, imbued the film with a sense of authenticity, by gathering up and solidifying the meanings and associations that had become attached to the film in the years prior to 1997. However, as I will go on to explain, the kinds of authenticity that became associated with the film in the DVD and Internet age were of a particular kind, drawing on the distinctive qualities and characteristics of the film and its production history in order to perpetuate the sense that The Evil Dead, in its DVD as well as its video and theatrical form, had appeals and qualities that marked it out from other horror films.

UP CLOSE AND PERSONAL: DVD COMMENTARIES AND THE IMPORTANCE OF PERSONALITY

As the market in laserdisc and DVD special editions grew throughout the late 1990s, a range of companies began to spring up which specialised in the restoration and re-release of independent genre and art-house titles. Two companies played a key role in bringing The Evil Dead back into the public consciousness – Elite Entertainment (which, from 1994, began to release restored laserdisc versions of independent horror milestones like Night of the Living Dead, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and, in 1998, The Evil Dead) and Anchor Bay (a company which, from 1997, began to specialise in the release of DVD versions of films from a range of directors associated with genre, art-house or independent productions). Anchor Bay’s adoption of The Evil Dead in the DVD age had two clear kinds of impact on its cultural reputation. Firstly, and as Klinger has noted, the release of a film in the DVD special edition format can allow it to become part of a particular canon of films, and, in the sense that The Evil Dead was taken on by a company that would subsequently release films by Peter Jackson and George A. Romero as well as Wim Wenders and Monte Hellman, this enabled the film to be reframed as a key post-1950s independent film title. As a result, Anchor Bay’s many special edition versions of The Evil Dead could be seen as a recognition that this was a film that stood out from the genre of horror in which it was putatively located, and that the film could therefore be appreciated not just as an important horror film but also, more broadly, as a milestone of American independent filmmaking.

This reframing of The Evil Dead on DVD did not, however, lead to the severing of the film’s previous cult-friendly associations. On the contrary, certain capabilities and aspects of the DVD special edition gelled perfectly with The Evil Dead’s already established qualities and appeals, leading to the amplification of some of its most distinctive cult characteristics. Up to this point in time, a central aspect of the film’s making of story (as recounted by, for instance, Bill Warren and Jonathan Ross) had always been the personalities of the Renaissance partners: their determination, their hard work but also their modesty and sense of humour. The release of the first special edition of the film (on DVD and laserdisc) in 1999 included one feature which would serve to effectively harness this aspect and would remain at the heart of the appreciation of The Evil Dead, by fans and critics, in the DVD age: two commentary tracks, the first by Raimi and Tapert and the second by Campbell. What seemed to be most effective about Campbell’s track, in particular, was the way in which it represented the two interdependent qualities of the Renaissance partners that had, arguably, helped to make The Evil Dead a cult success in the first place: their ability to be entirely serious and committed to the film but to have fun, and to poke fun at the film and each other, at the same time. As DVD Times noted, in its review of the Campbell commentary on the 2003 Anchor Bay UK Evil Dead trilogy box set, ‘whilst he’s forthcoming with any information the listener may require, that doesn’t stop him from doing it in a frequently entertaining, and indeed hilarious, manner’ (Anon. 2003).

Timothy Corrigan has argued that ‘the economics of production and distribution’ of such low-budget films as Night of the Living Dead can serve as ‘a way of claiming a kind of common or secret ground for audiences who might feel closer to Pittsburgh or grainy stock than to the glamour of Hollywood’ (1991: 27). This notion that low-budget production histories can allow for a sense of closeness and a more intimate access to a film and its makers seems key to the appeal of The Evil Dead’s commentary tracks, and the commentaries’ blend of information and humour supports this sense of closeness, in a number of ways. Firstly, both commentaries not only highlight the film’s references to other films (and other key horror films in particular), but also the ways in which aspects of the film relate to the filmmakers’ background and previous filmmaking history. Consequently, the commentaries not only note the use of techniques first employed in earlier Super-8 productions and identify relatives and friends who shemped for the principal actors in certain scenes, but also explain the origin of certain props and costumes included in the film (for example, the appearance of Campbell’s father’s old tape recorder on which Raimi and Campbell had recorded skits during high school and the inclusion of t-shirts from Raimi’s college and summer camp). Such information clearly increases the scope for acquiring specialist knowledge about the film, but a form of specialist knowledge that relates, specifically, to the personal universe of the Renaissance partners, helping to further strengthen the sense that a key way in which the film can be appreciated and understood is through knowledge about the history of the relationships between, and experiences and personalities of, these three individuals.

Complementing this focus on personal relationships, the commentaries have been celebrated for their ‘hilarious line in self-deprecating wit’ (O’Neill 2001: 20) and the ‘affectionate potshots’ (Hewitt 2001: 131) Raimi and Campbell make at the film and, across commentary tracks, at each other. The threesome’s self-deprecation takes a number of forms. Campbell, throughout his commentary, adopts the position of a sarcastic audience member (noting, during a suspense sequence, that ‘if she can only get her hands on those keys! Is she going to get in or not folks? I’m terrified’), and a sceptical audience member (commenting on the fact that, in films of this kind, characters always wander into the woods, talking to themselves for no apparent reason). In addition to this, Campbell’s comments on his performance drip with sarcasm (‘this was high drama, method acting’), he notes that Raimi’s performance on the soundtrack illustrates that he’s ‘a bigger ham than I’ve ever been’, and he returns time and again to a ‘cheesy matte shot’ of the moon with a square visible around it, noting, at a later point in the film, ‘there’s the darn square matte shot, dontcha love it?’ (2002a). On the other commentary track, Raimi and Tapert complement Campbell’s approach by frequently appearing to be amused and slightly embarrassed by their naivety and the ill-considered aspects of the production. Raimi notes, for instance, that the question of why a poster for The Hills Have Eyes would be in the cellar of an abandoned farmhouse ‘makes me ask some tough questions of myself’, and he laughs heartily at the absurdity of Campbell being trapped by some shelves during Cheryl’s possession sequence. In addition, all three point out the use of basic special effects in the film (the It’s Murder! beams, the ‘basic rubber hand’, the fog and red light which constituted ‘the world’s cheapest effect’), and note their incredible irresponsibility during the course of the production, breaking borrowed cameras, shooting guns towards the camera and breaking real glass near actors which, as Tapert notes, ‘nowadays safety officers wouldn’t let you do’ (in Raimi & Tapert 2002).

What is being emphasised here is the chaotic messiness of the production, the fact that, due to time spent financing the film, the filmmakers had to rush to begin filming in Tennessee with minimal pre-production planning. Arguably, what this focus on naivety and messiness conveys is the potential interchangeability between the filmmakers and those audiences watching the film at home. On the one hand, Campbell acts out the potential responses of those watching the film and/or addresses the viewer directly (illustrating, once again, that audience response to the film was always of central importance to the Renaissance partners), and, on the other, all three bring the audience closer to them by unapologetically revealing their lack of experience and the ways in which this impacted on the production of the film and the finished work itself.

Interestingly, all of these tendencies stand in contrast to some of Barbara Klinger’s observations about the role of ‘behind-the-scenes information’ in the special edition laserdisc and DVD sets for higher-budget titles made by Hollywood studios. As Klinger argues, in relation to commentary tracks and other behind-the-scenes information on such special editions:

As the viewer is invited to assume the position of the expert, s/he is drawn further into an identification with the industry and its wonders. But this identification … is based on an illusion. Viewers do not get the unvarnished truth about the production; instead, they are presented with the ‘promotable’ facts, behind-the-scenes information that supports and enhances a sense of the ‘movie magic’ associated with the Hollywood production machine. (2001: 140)

While it is certainly the case, as Jim Barratt notes, that the making of stories of low-budget cult films like The Evil Dead and Bad Taste focus on the ‘promotable facts’ about these films, these facts serve, in contrast to the ‘behind-the scenes’ features discussed by Klinger, to break rather than sustain the illusionism and ‘movie magic’ associated with Hollywood feature filmmaking. Consequently, what seems to distinguish The Evil Dead special edition is that the key ‘promotable facts’ about the film are those that do give ‘the unvarnished truth’ about the production, bringing fans closer to the film’s makers (as fallible human beings) and, as Barratt notes, ‘treating fans to an insider’s view that favours the unconventional, encouraging their greater personal investment in the film’ (2008: 27).

In order to gain a further sense of the reasons why fans find The Evil Dead to be unique, distinctive or special, I surveyed 406 user reviews of the film from www.imdb.com (stretching from 1999 to 2008 and posted by fans predominantly from the US, Europe, Australia and Canada). From these, I particularly focused on a sample of 100 reviews from those who either stated that The Evil Dead was their favourite film or favourite horror film and/or those who noted that they had watched the film when they were young and had gone back and rediscovered it on DVD. The sense that fans’ ‘personal investment’ in The Evil Dead has been informed by the ever-increasing circulation of anecdotes, facts and stories about the making of the film was evident in these user reviews, in three key ways. Firstly, the importance of these making of stories to fans is conveyed by such comments as: ‘after listening to the commentary on the special edition DVD, I appreciate the film even more’ ((n.e.o), Everson, 30 May 1999), and ‘hearing all the wild stories about the film’s production is as fun and interesting as watching the movie itself’ (meader82, Maine, 17 December 2004). Such comments illustrate some of the ways in which the increased publication and circulation of such stories (in print and DVD form) have served to heighten The Evil Dead’s cult appeal, allowing for a richer appreciation of the film itself while also allowing the commentaries to serve as entertaining proxy cult texts in their own right. As a consequence, these commentaries, for fans, are appreciated, to use Deborah and Mark Parker’s terms, as ‘another text’ but a text that is still ‘intimately related to the film’, enhancing and ‘complicating the experience’ of watching The Evil Dead (2004: 13).

Secondly, the extent to which background information about the filmmakers enhances an appreciation of the film itself is illustrated by user reviews that read and assess the film in relation to the personalities of those who made it. The film, for a range of reviewers, ‘reeks of passion’ (dissolvedpaul, Scotland, 12 July 2000), enthusiasm ‘drips down the screen’ (meader82, Maine, 17 December 2004), you can ‘literally feel the presence of a young, nervous but confident and strikingly talented director at the helm, throwing his heart and soul into the production’ (Super_Fu_Manchu, London, 9 February 2004), and there is an ‘abundance of pure brio, passion, energy and enthusiasm’ which excuses the film’s ‘cheesy’ production values (Woodyanders, New Jersey, 17 April 2006). However, at the same time, certain reviews acknowledge that ‘Raimi and friends decided to make a low budget zombie flick mainly for fun’ (Manthorpe, Texas, 16 August 2004),14 or note that the film ‘gives the feeling of being just a bunch of friends who went out to the woods and cut themselves off from society for a while to see what they could come up with’ (Michael DeZubiria, China, 5 May 2008). What these comments suggest is that, for these fans, a personal investment in the film is informed by the filmmakers’ dedication, talent and enthusiasm, but also their humanity (conveyed through references to heart, soul and passion) and their consummate ordinariness (through the identification of this group as just a bunch of friends having fun).

It is this last identified quality (a sense that the filmmakers are ordinary and relatable) which also seems to inform a further strand of appreciation that emerges in the IMDb user reviews of the film: the film’s status as an inspiration to amateur, independent filmmakers everywhere. As one reviewer explains, ‘I am an aspiring film student, so I can appreciate fully what the filmmakers had to go through in order to make this film’ (Seven-6, Omaha, 11 July 1999), while another reviewer notes that, ‘I always feel more of a connection to films that are made on low budgets than the big studio flicks, because I’m an aspiring filmmaker myself. Watching a movie like this inspires me, especially since I’ve always wanted to make a horror movie’ (mattymatt4ever, New Jersey, 7 January 2003). Such comments illustrate the importance, to these fans, of the Renaissance partners’ status as amateur filmmakers working on a low budget, the way in which the obstacles and difficulties faced by these filmmakers draw fans closer to the film and, equally, the way in which the film itself (and its associated production background) can serve as a kind of ‘how to’ manual for prospective amateur filmmakers. As one reviewer notes, as well as being ‘entertaining’ the film ‘is also educational in the sense of filmmaking’ (ryang_film, USA, 5 February 2007), with the reviewer then going on to recommend The Evil Dead, Robert Rodriguez’s El Mariachi (1992) and Kevin Smith’s Clerks (1994) as the three films that aspiring filmmakers should watch before making their movie.

Such comments seem to indicate, once again, that the charm of The Evil Dead’s making of story is that it suggests a potential interchangeability between the film’s makers and its fans. Just as Campbell, in his commentary track, can place himself with, and become a member of, the film’s audience, so these fans can imagine themselves being in the position of the film’s makers, either feeling inspired to make a film of their own or imagining the obstacles the filmmakers faced and respecting their ability to overcome such obstacles. As one reviewer notes, this film ‘was made by college students who, in spite of being amateurs, put their best efforts into it. They did a great job and as a result the film is dear to my heart’ (LauraH2477, FL, 22 November 2003). This level of investment (inspired and informed by the film’s colourful making of story) illustrates how, at least for these fans, The Evil Dead could be seen as more than just a good horror film but also, to quote Bruce Kawin, a cult film ‘with which we, as solitary or united members of the audience, feel we have a relationship’ (1991: 20). However, the focus on heart, soul, passion and personality in these IMDb reviews also, in some cases, serves to distinguish and authenticate The Evil Dead in other ways, most prominently, and as I will show in the next section of this chapter, in relation to the subsequent changes in horror production and to the qualities and characteristics of the film’s two sequels.

CULT BY DISTINCTION: THE EVIL DEAD AS THE TRILOGY’S ILLICIT LITTLE BROTHER

In a significant number of the IMDb user reviews of the film, the distinctiveness of The Evil Dead is illustrated through comparisons with contemporary, post-1985 horror films, and, in particular, higher-budget Hollywood horror productions. For many of these fans, while The Evil Dead is stylish and inventive and the filmmakers are appreciated for caring about what they were doing, more contemporary horrors –including Scream (1996), I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997), Hostel (2005) and even The Blair Witch Project (1999) – are presented as ‘diluted’, ‘watered down’, ‘run of the mill’ and ‘recycled’ (Adrian Collazo, Washington, 23 April 1999; Resident Hazard, Plymouth, MN, 7 August 2004; ecw06, United Kingdom, 20 September 2006; Charlotte Kaye, United States, 29 March 2007). Many of the reviewers do note that The Evil Dead isn’t a perfect film, focusing, in particular, on its inexperienced actors, low production values, weak character development and plot, and, in some cases, the supposed cheesiness and unconvincing nature of the film’s special and make-up effects. However, for many of these fans, these weaknesses can be excused because the film serves as a key example of what is missing from much contemporary horror: namely, heart, soul, grittiness and rawness. For one fan, The Evil Dead is to be valued because it is ‘opposed to bland, big budget things’ (bmovieman3000, United States, 17 June 2008), while, for another, The Evil Dead is a film to be cherished because it ‘puts heartless hollywood [sic] mass-produced movies to shame’ (Super_Fu_Manchu, London, 9 February 2004).

In fact, the rudimentary nature of two of the film’s elements – acting and special effects – is, for some fans, key to the film’s charm and appeal. In terms of acting, Campbell’s understated and rather amateur performance is frequently valued for making Ash appear to be a normal person rather than a Hollywood hero, allowing fans to believe in his predicament and thus the film’s horror to seem more realistic. This perspective on Ash was also held by the Within the Woods site creator, Mark Dutton, who noted to me that Campbell’s ‘wooden performance’ was central to the film because, in that situation, most people would also be ‘inept’ and this allows him to put himself in Ash’s shoes and to root for him. As he noted, ‘if nothing else the lack of Campbell’s experience at that stage helped the movie and I for one wanted him to survive’ (email to author; 21 July 2008).

In terms of the film’s special effects, what is valued, by many IMDb reviewers, is their rough and ready quality but also the authentic old-style craft and workmanship that had gone into the production of these effects. As one fan notes ‘I actually prefer this old style mix of make-up effects and stop motion animation to pretty much all of today’s films’ (Charlotte Kaye, United States, 29 March 2007), while, for others, the ‘rough hewn’ special effects of Tom Sullivan and Bart Pierce are an example of ‘down and dirty filmmaking’ which is far preferable to ‘today’s multi-million costing soulless CGI’ (Steven Nyland, New York, 27 May 2006; meader82, Maine, 17 December 2004; Paul Andrews, United Kingdom, 3 December 2004). In fact, in wider Evil Dead fan circles, a cult following has built up around one of the creators of these effects, Tom Sullivan. Subsequent to his involvement in The Evil Dead, Sullivan created art for role-playing games, and then worked on Evil Dead II and The Fly II (1989). However, after discovering that ‘the bigger [the] film productions I worked on the fewer artistic contributions were required of me’ (n.d.), Sullivan went back to producing his own art and prop replicas (through his company Dark Age Productions) and created the Tom Sullivan Movie Memorabilia Museum, which features props and art from The Evil Dead and which has toured fan conventions across the US.

Such activities have been appreciated by, for instance, a range of Evil Dead fans on the Within the Woods website, who, in a discussion forum on the site, have commented on their love of the film’s props (most specifically, the Sullivan created Book of the Dead and Kandarian dagger). Their appreciation for these props takes two forms. Firstly, the fans on the forum swap experiences of meeting Sullivan at conventions and note how open and friendly he is (a quality illustrated by the fact that he has been a supporter of both of the main Evil Dead fan websites). They also frequently discuss their collection of replica Evil Dead props, and swap photographs of props featured on Sullivan’s Dark Age Productions website. Secondly, four of the forum posters have also produced their own Evil Dead replica props and artwork, with two posters having made replica Books of the Dead for artwork projects at college and with all four frequently swapping tips on how to produce their own Books of the Dead and Kandarian Daggers. As noted in the previous chapter, what this focus on Sullivan and his props illustrates is the extent to which cult appreciation of The Evil Dead is informed, at least for some fans, by the desire, in wider horror and scifi fan circles, to have effects work (and other related work, such as film props and art) ‘treated as a legitimate (i.e. authored and hence authorised) form of aesthetic expression’ (Michele Pierson in Hills 2005: 89). And, as illustrated by the comments of the IMDb reviewers given above, this focus on the artisanal props and effects work of Sullivan (and his movement away from the increasingly digitised world of film special effects) seems to complement the wider fan appreciation of The Evil Dead as an authentically ‘raw’, ‘grungy’, ‘gritty’ and ‘down and dirty’ piece of filmmaking.

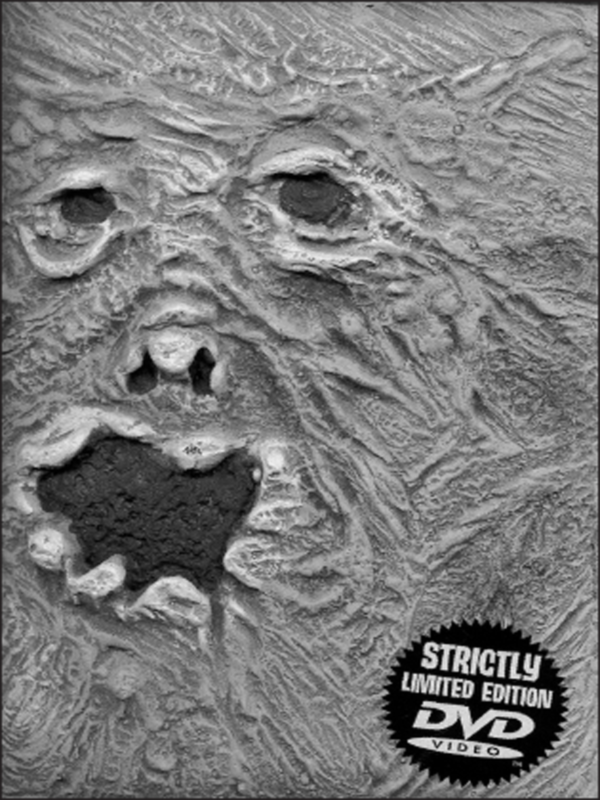

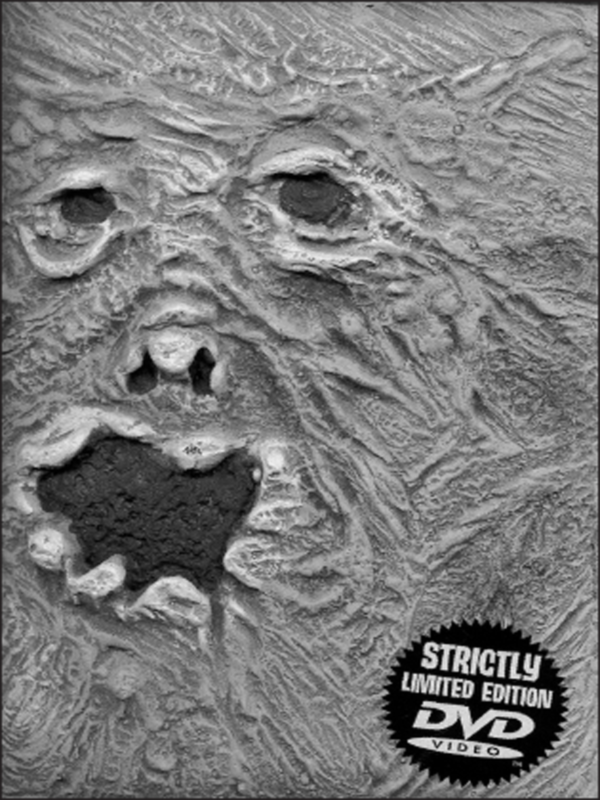

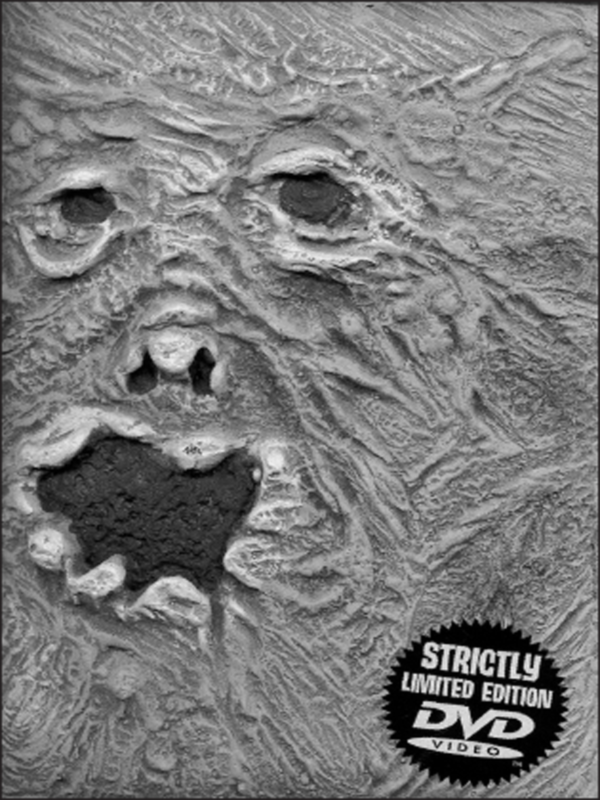

Indeed, Anchor Bay was quick to recognise the importance of Tom Sullivan’s artwork to the image and appeal of The Evil Dead. In 2002, Anchor Bay released a limited edition Book of the Dead version of The Evil Dead on DVD, with a latex cover sculpted by Sullivan and 24 pages of Sullivan’s illustrations from pages of the book, both of which were designed ‘to replicate his creation of the book found in the film’ (Anon. 2002a). This DVD version of the film eventually won an award for best packaging at the Fifth Annual DVD Awards in 2002, with the judges noting that ‘of all the sharp, shiny packages with their fold-out boxes and tricky sleeves, this brilliant horror-comedy arrives in a packaging that perfectly reflects and introduces the content. And it is, by far, the most clever and unique DVD packaging we’ve seen yet’ (Anon. 2002b). The success of Anchor Bay’s packaging, then, seemed to be based on the way in which it tapped into a valuation of The Evil Dead as a unique, clever, creative film, whose artistry and idiosyncrasies were in sharp contrast to mass-produced, ‘bland’ Hollywood horror, to ‘soulless CGI’ and, in the case of the DVD itself, to ‘sharp, shiny’ conventional DVD packaging.

Anchor Bay’s award-winning Book of the Dead DVD

However, for fan reviewers on IMDb, it wasn’t just the film’s raw, gritty, artisanal qualities that distinguished The Evil Dead from more contemporary horror films. What was particularly distinctive about these user reviews was that the same kind of experience was described, time and again, when it came to discussing the history of their relationship with the film. For many of these fans, their first encounter with The Evil Dead had been at some point in the 1980s when the film was available on home video and they were very young teenagers (the age range cited is generally between ten and 14, although a couple of reviewers state that they were only five or six years old). In all these cases, the film had stood out for them because it had ‘scared the hell’ out of them (Dennis G. Barnes, Ottawa, 28 September 2003) and, for many, had led to nightmares and sleepless nights. However, in many cases, what is also then recounted is the fact that this fear and fright has never gone away and that the film continues to scare them (at least a little) when they watch it on DVD in the present day. This response to the film may not seem particularly surprising, when considering that this, after all, is what horror films are supposed to do and, indeed, this is absolutely what Raimi and company were focused upon when they planned, wrote and shot the film in 1979. However, this open declaration of the film’s ability to scare them (and the value of this to these fans) seems to fly in the face of much recent academic work on horror fan communities on the Internet. For instance, while both Mark Jancovich and Matt Hills have noted that seasoned horror fans (which many of these IMDb reviewers seem to be) tend to value ‘the authentic “low budget”’ horror film over its ‘inauthentic “high budget”’ counterpart,15 they have also argued that many hardcore horror fans often distinguish themselves from younger fans of higher-budget horror by ‘deny[ing] that horror films frighten them’ and ‘assert[ing] that they don’t frighten but only amuse’ (Jancovich 2000: 31 & 34).

In contrast, the valuation of The Evil Dead in the press as a film that ‘still packs quite a punch’ (O’Neill 2001: 20) and ‘still delivers a jolt to synapses’ (Hewitt 2002: 150) is mirrored in many IMDb fan reviews of the film, where much of the film’s value and significance relates to the fact that The Evil Dead is a film which ‘still has the power to disturb’ (Shawn Watson, 7 October 2006). There are a number of factors that appear to feed into this evaluation of the film, but an interesting and rather surprising one is that, for a significant number of these fans, The Evil Dead possesses qualities that make it distinct from, and in some cases superior to, the film’s two sequels, Evil Dead II and Army of Darkness (1992).16 This situation was surprising for me because I had assumed, when beginning research for this book, that most fans of the first film would also be fans of the sequels. Certainly, when stepping back and looking at the reception of The Evil Dead trilogy as a whole, it is clearly the case that Evil Dead II is the most revered and popular of the three films, for both fans and film critics and journalists. From a broad perspective, Evil Dead II generally has a higher user rating on IMDb (at the time of writing, 7.9 out of ten as opposed to the first film’s rating of 7.6), and has been considered, in a number of retrospective articles, as superior to its predecessor because it’s seen to be more imaginative, inventive and entertaining. For Sam and Rebecca Umland in Video Watchdog, for instance, Evil Dead II is valued for being more purposeful, in the sense that, unlike its predecessor, it has a more interesting plot and a more consistent style, meaning that the second film is The Evil Dead ‘as it “should have been”’ (1998: 37).

From the more specific perspective of Evil Dead fandom, discussions and features on the film’s two main fan websites seem to privilege the second and third instalments of the trilogy. On Deadites Online, for instance, a page called Ashplay (which collates pictures of fans dressed up as Ash) features fans dressed, in most cases, as the version of Ash featured in the second film, while, on Within the Woods, lists of favourite dialogue and soundbites from the films focus on oneliners and quotes taken predominantly from the two sequels. Mark Dutton, creator of the Within the Woods website, discussed this fan focus on the second two films in an email exchange with me in 2008. He noted the fact that, while he is also a huge fan of the first film, Evil Dead II was his favourite from the trilogy. For him, ‘the strength of the Evil Dead franchise IS Ash’ and ‘he didn’t truly become “Ash” until Evil Dead II which is why that movie and Army will always be the ones people speak of whilst the original movie will always remain in Ash’s shadow’ (email to author; 3 August 2008). For Dutton, the development of Ash as an iconic film character in the two sequels (supported by the use of more memorable dialogue in both films, and the merchandising that emerged from the third film) means that the two sequels ‘remain more securely in our consciousness’ and that the first film ‘will never quite reach the levels of pop culture fame as its big brothers’ (email to author; 21 July 2008).

However, despite this appearing to be the most dominant perspective on the trilogy in The Evil Dead fan circles, there does appear to be a substantial group, within the broader The Evil Dead fan community, who are predominantly fans of the first film rather than the trilogy as a whole. Indeed, a number of IMDb user reviewers acknowledge that they are flying in the face of popular Evil Dead fan opinion by preferring the first instalment, with one reviewer noting that they favour the first film ‘even though everyone I know says 2 is the best’ (Eviljomr, Texas, 8 December 1999) and another noting that ‘the original Evil Dead is worth much more to horror fans than a “lead in” to the more popular sequels’ (TheBlackGoat, USA, 3 October 2000). For these fans, the primary reason for this preference relates to the film’s ability to scare and disturb, a quality that, as the quote above indicates, makes the film (unlike the sequels) a proper horror film. As one reviewer notes, ‘I was disappointed that Raimi decided to veer further into “tongue-incheek” hi-jinks and laughs rather than the more serious tone of Evil Dead I … Watch all three and tell me which one’s the real horror film’ (Adrian Collazo, Washington, 23 April 1999).

Importantly, this criticism of the sequels because of their greater focus on ‘hi-jinks’ and ‘laughs’ does not mean that The Evil Dead is perceived to be free of humour. Instead, for many IMDb reviewers, what is valued about the first film is the subtle blending of scares and pitch black comedy, a blend that allows the horror to be more ‘twisted’, ‘creepy’, ‘uneasy’ and ‘grotesque’ (Filmjack3, United States, 22 April 2002; Matthew Williams, England, 1 January 2007; jksburns, England, 16 June 2002; insomniac_rod, 7 November 2004). For these fans, this ability for the film to be both humorous and terrifying makes the ‘shocks all the more uneasing [sic]’ (TimothyFarrell, Worcester, MA, 1 October 2006), ‘the horror all the more horrible’ (jksburns, England, 16 June 2002) and allows the film to be ‘funny without taking away’ its ‘gruesome and creepy feel’ (Matthew Williams, England, 1 January 2007). In contrast, a number of particularly dedicated fans of the first film associate the more explicit slapstick of the two sequels with these films’ more commercial focus. While, for these fans, the darker comedy of the first film seems to gel with its ‘claustrophobic, cold, distant, hopelessness’ (Steven Nyland, New York, 27 May 2006), its grainy, low-budget ‘look, feel and tone’ (Charlotte Kaye, United States, 29 March 2007) and its ‘nitty gritty’ ‘weird oogy feeling’ (Lance, USA, 26 June 2005), the ‘commercialised sequels’ are considered to be not as scary, with ‘the unnecessary slapstick’ being seen to ‘plague’ the second two films and ‘bombard’ the viewer, succeeding in turning ‘the franchise into a comedy show’ (imacrazyperson, Australia, 23 September 2004; marquis de cinema, Boston, 18 July 2001; David O’Brien, Ireland, 25 April 2007). Furthermore, one of the most valuable aspects of the sequels for many fans – the greater focus on Ash – is seen, by some, as these films’ central weakness. As one reviewer notes, in Army of Darkness, ‘Ash Williams turned into a chainsaw-wielding, one-line-spewing tough guy-comedian, and the grim nature of the original seemed lost in the chaos’ (MovieAddict2008, UK, 9 March 2005).

For these dedicated supporters, what is therefore valued about The Evil Dead is the way in which the film’s low-budget aesthetics and more subtle, dark humour combine to make the film that much more scary. In contrast to the fans discussed by Jancovich and Hills, this valuation means that scariness becomes positively associated with the lower-budget and more ‘rough hewn’ first film, while more overt comedy is seen as a consequence of the more commercial nature of the sequels. In fact, the more implicit comedic tone of the first film has been cited, by Julian Petley, as one of the reasons why it was attacked and scapegoated by British moral campaigners in the early 1980s. As Petley has noted, for those people who were interested in and knew about the conventions of horror, ‘the comedy element’ in The Evil Dead ‘shone through very clearly’ but, when Petley showed the film to a group of friends who weren’t interested in or familiar with the horror film, they were ‘absolutely sickened and revolted by it’ (2003). Consequently, the first film’s more subtle dark humour seemed to make it more specialist and impenetrable for those who were not familiar with or interested in the horror genre. Equally, one could argue that this element also made the first film less easy to categorise: neither straight horror nor straight horror comedy, The Evil Dead was, as a reviewer on dvdreview.com has noted, ‘highly controversial at the time of its release because many people did not exactly know what to make of it’ (Henkel 1999). In contrast, Raimi commented, at the time of the release of Evil Dead II, that he wanted the sequel ‘to have a wider appeal so we took out some of the gore and put in a couple of Three Stooges type gags’ (1988),17 while Campbell has also noted, more recently, that while Evil Dead II was an explicit ‘horror comedy’, the first film ‘is for purists who just want carnage and mayhem’ (in Kirkland 2007: 19). Indeed, the filmmakers have stated, on a number of occasions, that the comic elements of the first film were actually unintended. As Raimi notes in his DVD commentary, the laughter of audiences on the film’s initial theatrical release was a surprise to him as they were ‘really trying to make a horror picture’ (in Raimi & Tapert 2002).

Such comments seem to relate back to the messy imperfection of The Evil Dead, which, for Sam and Rebecca Umland, made the film inferior to its more purposeful sequel. Another, extremely famous, example of The Evil Dead’s imperfection is the notorious tree rape sequence, which was cut from the film’s first UK video re-release (by Palace Pictures in 1990), and which has been seen, even by some of the film’s supporters such as Petley, as the film’s primary flaw. Indeed, Raimi has now publicly acknowledged, on a number of occasions, that he regrets the inclusion of this sequence in the film, noting that his ‘judgement was a little wrong at the time’ (2003). Nonetheless, this sequence, however ill-advised, has also been seen, by a number of commentators, as a symbol of the film’s low-budget, amateur origins, giving it an appropriately illicit edge. As one of the film’s British marketing producers, Chris Fowler, has noted, the film’s tree rape sequence ‘fitted in with the transgressive edge of the film’ (2003), while, for a reviewer in Empire, this scene was symbolic of ‘the grungy edge that condemned the film to the infamous Video Nasties list’ (Hewitt 2001: 131). Indeed, the tree rape’s status as a symbol of the low-budget illicitness of the first film has also been acknowledged by a number of IMDb user reviewers, with one reviewer noting, for instance, that the ‘daring’ nature of scenes like the tree rape is what ‘separates the first [film] from the next two’ (marquis de cinema, Boston, 18 July 2001).

What this all suggests is that many of those who particularly value The Evil Dead tend to focus on those qualities that distinguish the first film from its sequels, with the majority of these qualities being intrinsically connected to the first film’s low-budget, amateur origins. The film’s grainy look gives it ‘a substantial, raw, rattling, unrelenting power and intensity’ (Woodyanders, New Jersey, 17 April 2006) and ‘is part of its charm’ (suspiria10, 4 May 2003), the subtle (or unintended) dark comic elements contribute to the film’s twisted, creepy, weird quality, and the ill-advised, bad taste tree rape sequence symbolises the illicitness and notoriety that is missing from the film’s sequels. Furthermore, it is the very fact that these qualities are absent from the sequels that seems to more firmly associate The Evil Dead with the ‘cult’ label, even for those who prefer the second film. In DVD Times, for instance, a reviewer states that The Evil Dead is ‘considerably less enjoyable than its two sequels’ but then also acknowledges that it ‘has a strong cult following, many of whom prefer the darker, more horrific tone’ (Anon. 2001), while, for Mark Dutton of Within the Woods, it may be the case that the two sequels ‘remain more securely’ in the ‘consciousness’ of fans but he still believes that ‘within the context of the phrase “cult movie” the original film is a far better example’ (email to author; 3 August 2008). The wider popularity of the two sequels has therefore served, for many fans and critics, to further emphasise the low-budget, amateur qualities of The Evil Dead and to turn it into the neglected and marginalised bad little brother of the trilogy: the film that has retained a ‘cult’ following and thus fully deserves, even for those who prefer the sequels, the ‘cult’ badge of honour.

While, in The Evil Dead fan circles, the first film could be seen to have a distinctively marginal and illicit status, this is contradicted by the ready availability of The Evil Dead in remastered, uncut DVD form. In fact, the DVD market has been flooded with a plethora of different The Evil Dead special editions. At the time of writing, Elite and Anchor Bay have released, between them, six different DVD versions of The Evil Dead, with each one including more extras, more stills and more behind-the-scenes footage than the last. As many DVD reviews of the film have noted, the re-mastering process has heightened the impact of the film’s sound design and camerawork (elements of the film that are frequently valued by fans on IMDb, in the sense that they illustrate the incredible technical proficiency of Raimi and his crew). However, at least for many of these DVD reviewers, the re-mastering process has not been able to eradicate the low-budget grainy quality that constitutes one of the film’s key attributes for many fans.

Furthermore, the fact that the film itself is no longer scarce or unavailable has been countered, or perhaps compensated for, by the fact that some of the filmmakers’ original Super-8 short films and the prototype film, Within the Woods, are still legally unavailable. The Within the Woods website features pages that list and outline the details and titles of many of these previous short films, and knowledge about these shorts seems to have grown subsequent to the publication of Bill Warren’s book (which features a complete filmography of Raimi and company’s short filmmaking history). Consequently, much discussion has occurred, on the Within the Woods forums, about how to obtain downloads of Within the Woods online and which conventions to attend, in order to search for video copies of some of the early shorts. More recently, the fascination with Within the Woods and the earlier short films has led fans to upload acquired copies to YouTube, with some uploads being pulled as copyright holders cotton on to the fact that fans are making them available.

In 2002, Anchor Bay added fuel to the fire of fascination around Within the Woods when they announced that they would be including it as a DVD extra on their Book of the Dead DVD Special Edition. However, at the last minute, the extra was withdrawn, due to unspecified copyright problems, leading to further fan speculation as to why this had occurred. Fans on the Within the Woods website surmised that the copyright problems were probably due to the fact that, because the film had been an amateur production, certain products had been included in it without the makers having sought permission from the relevant companies. As one Within the Woods poster noted, the mysterious pulling of this extra would ‘go down in cult horror legend’ (Evil Ed, Belfast, 13 August 2005), a situation that illustrates one way in which the amateurish aspects of low-budget productions like The Evil Dead can work, as time goes by, to solidify a film’s cult reputation and continue to propel fans’ fascination with that film and its production and pre-production history.

In a now classic article on the British critical reception of Straw Dogs (1971), Charles Barr concludes that ‘films which always tend to suffer critically are those which fall between categories’ (1972: 21). While Barr is here considering the reasons why particular films are, or have been, critically derided or censored, the case of The Evil Dead illustrates that a film’s defiance of categories can also feed into its ability to be termed and appreciated as a cult film. The Evil Dead, for many fans and critics, is a film that is disturbing but humorous, rough and ready but technically proficient, relatable and personal but also weird and illicit, the most cult The Evil Dead film but not the most popular or revered The Evil Dead film. Throughout its post-release afterlife, The Evil Dead has continued to defy categorisation at every turn, perpetuating its status as a unique film experience and its status as a distinctly unprogrammatic cult film, with the imperfections, accidents and unintentional aspects of the film and its production serving to strengthen rather than diminish its cult status.