As outlined in previous chapters, the decision, by the Renaissance partners, to make a horror film was centrally informed by economic considerations: the fact that, consistently and especially during the period prior to the making of The Evil Dead, a range of independently made and cheaply produced horror films had been commercially successful, particularly with young audiences. As a consequence of this, the conception of The Evil Dead was the product of careful research by the filmmakers, who had studied a range of key horror films of the late 1960s and 1970s and identified the sequences and formal strategies that had proved to be most effective in terms of horrifying, engaging and shocking audiences. The result was a film that served as an inventory of the key patterns and trends that had emerged and developed in American horror cinema since the release of George A. Romero’s milestone independent horror film, Night of the Living Dead in 1968, while also drawing on scenarios and images from prior horror films.

The way in which this inventory approach brings together and fuses elements from different sub-genres of horror is clear when considering the film’s narrative and key dramatic premises. Firstly, the film employs the same basic narrative structure as the two films that would retrospectively be identified as the progenitors of the slasher sub-genre, Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978). Like these films, the central narrative focus of The Evil Dead is on a group of young people who are gradually killed, one by one, until only one survivor remains, and, as with The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, this group is made up of two couples and one difficult ‘outsider’ character (Franklin in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Cheryl in The Evil Dead). In addition, and as I will go on to illustrate, The Evil Dead also employs the distinctive and influential point-of-view patterns used in Carpenter’s film, commencing with shots taken from the point of view of the monster.

Secondly, the film also borrows narrative elements and formal strategies from what Geoff King calls the ‘more edgy and disturbing’ independent American horror films of the 1970s (2005: 7), most prominently Hooper’s film and Wes Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes. As in both of these films, the characters travelling to a remote location, and then disturbing or disrupting something or someone, initiates the horror in The Evil Dead. As a result, the characters are attacked by those they disturb, with the horror of the situation being informed by the fact that these characters are isolated and cut off from normality and the modern, civilised world. This focus on remoteness connects all these films with Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, which also capitalises on the inherent horror of isolation by setting much of its action in one boarded-up house which is slowly besieged by zombies. In addition, The Evil Dead also employs the same kind of formal strategies used by Romero and Hooper to depict and convey the isolation, helplessness and claustrophobia of these horrific situations, including canted angles, high and low angles, cluttered compositions, extreme close-ups and an inventive use of sound.

The Evil Dead, however, departs from the majority of these films by making its unknown/monster element entirely and explicitly supernatural. While the monsters of Hooper, Craven and Carpenter’s films are, at least explicitly, of this earth (allowing these films to explore the horror that lurks within humanity and within society),18 The Evil Dead’s demons are inspired by ideas from ancient history – the Sumerian Book of the Dead and its relation to ‘the netherworlds beyond death’ (Raimi quoted in Warren 2000: 36) – and threaten through their capacity to demonically possess the living. This focus on death and possession allows The Evil Dead to be placed in the wider tradition of gothic horror, and the more specific tradition of the possession film. As I will go on to illustrate, this means that The Evil Dead, whether consciously or otherwise, taps into gender issues in a way that is distinct from Halloween and other slasher films. The focus, particularly in the latter stages of the film, on the demonic possession of women and the impact of this on a tortured male protagonist seems to draw on iconic images and scenarios from the British Hammer Horror films of the late 1950s and 1960s, and the out-of-control females of William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973) and Brian De Palma’s Carrie.

In one sense, this mixing and fusing of elements from a range of different types of contemporary horror could explain why Sam and Rebecca Umland consider The Evil Dead to be an uneven film, when compared with what they see as the more purposeful, consistent quality of Evil Dead II. For them, the filmmakers seemed to be discovering ‘the film they really wanted to make’ as they went along (1998: 33), meaning that The Evil Dead, as a whole, has an inconsistent style and tone. Indeed, when first sitting down and watching the film through (for the purposes of analysing it for this book), I was struck by the way in which it can be experienced as a film of two halves. The first half can be seen to play out as an atmospheric horror which draws, both overtly and more implicitly, on the iconography and milieu of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and The Hills Have Eyes – the slow, tense pacing of the early section of the film, the bone and gourd-bedecked cabin interior, the focus on the sun, and the colour palette of the outside of the cabin surroundings as the characters first arrive.19 In contrast, there are dramatic shifts in the tone and pace of the film, from Cheryl’s possession onwards. The woods and ground outside of the cabin begin to take on the character of a gothic horror film set, with (as Raimi and Tapert note in their 2002 DVD commentary) the copious amount of fog allowing the cabin surroundings to resemble ‘the surface of the moon’. The possession of each character occurs quickly, leading to a more rapid pace in the editing as the film goes on. The film’s violence becomes more cartoon-like and messy, and its tone more demented and comedic (a goofiness which is largely absent, at least from the performances of the actors, in the early portions of the film).

This inconsistent ‘patchwork’ quality seems to relate not only to the Renaissance partners’ inventory approach to horror but also to the chaotic nature of the production, where scenes were rewritten and ideas reformulated as the production went along.20 In this respect, the film can be seen to possess exactly the kind of ‘collage’ quality that Umberto Eco famously attributed to many cult films. For Eco, a key appeal of many cult films was that, during production, ‘nobody knew exactly what was going to be done next’ and that, as a result, such films can be seen to play out as ‘a disconnected series of images, of peaks, of visual icebergs’ which ‘display not one central idea but many’ and fail to ‘reveal a coherent philosophy of composition’ (2008: 68). However, this is to disregard the more careful ways in which these different tones, styles and formal patterns are interwoven throughout the film. As outlined in the previous chapter, many fans of The Evil Dead value the way in which the film balances suspense, atmosphere, shocks, gore and comedy, a strategy that allows the film to play games with the audience while, simultaneously, maintaining its disturbing quality.

This tension between the film’s textual patchwork construction and its overall effectiveness as the ‘ultimate experience in gruelling terror’ will consequently be the primary focus of this chapter. On the one hand, the ‘collage’ of different sub-generic images and ideas employed in The Evil Dead can lead to the generation of different kinds of meanings. This particular kind of interpretation may cause alarm bells to ring in the heads of many Evil Dead fans. While, as Peter Hutchings notes, such 1970s horror film directors as Wes Craven ‘were wholeheartedly committed to the genre as a suitable vehicle for the expression of ideas’ (2004: 181), Sam Raimi has always distanced himself from attempts to find deeper, thematic meaning in The Evil Dead. As noted in earlier chapters, for him, the decision to make his debut feature a horror film was economic but also creative, in that the horror genre provided him with an appropriate framework in which to experiment with formal techniques and strategies of suspense. In this respect, Raimi saw The Evil Dead as, primarily, a vehicle for formal experimentation and the initiation of affective response from the audience, rather than as a film that would explore and develop the thematic concerns of the horror genre. However, as Eco acknowledges, the fusing of ideas, images and strategies from different textual traditions can allow these ideas, images and strategies to ‘speak to each other independently of the intention of their authors’ (ibid.). Consequently, one focus of this chapter will be to consider how the mixing of elements from different horror sub-genres contributes to the generation of a range of, often contradictory, meanings that tap into a series of, equally contradictory, ways of creating and generating horror.

In addition, this chapter will also consider how these contradictions, and the shifting tones and perspectives within the film, feed into the disorientating, disturbing and creepy nature of the film as a whole. As noted in previous chapters, fans of The Evil Dead value the film’s ‘throbbing personality’ but also its ‘claustrophobic’, ‘cold’ and ‘distant’ qualities (tomimt, Finland, 20 February 2006; Steven Nyland, New York, 27 May 2006). By exploring the ways in which the film manages these shifts in tone, this chapter will illustrate how The Evil Dead attempted to squarely locate itself in the horror genre while also offering something new, original and different.

SUSPENSE, SHOCKS AND GAGS: PLAYING GAMES WITH THE AUDIENCE

In her study of the initial slasher or ‘stalker’ film cycle, which ran from Halloween in 1978 to Hell Night in 1981, Vera Dika discusses the expectations that are generated by these films’ suspense strategies. As she notes, the suspense sequences that precede attacks in these films encourage the audience to take part in a ‘guessing game’, focused around the questions ‘where is the killer?’ and/or ‘when will he strike?’ (1987: 88). For Sam Raimi, it was this gaming quality, and its dependence on the careful staging of suspense sequences, that served as his initial point of interest in the horror film. For a person fascinated with magic and playing tricks on an audience, the process of creating suspense was a new skill that he wished to perfect and add to his arsenal of filmmaking techniques. As he noted in an interview, ‘I would watch the suspense build in a picture, and it would be released, and the audiences would jump and scream, and I thought, this is kind of fantastic; they are being brought to a level here, and how long can we sustain that level?’ (in Warren 2000: 37).

After practising these techniques in two of his previous short films, Clockwork (1979) and Within the Woods, The Evil Dead constituted Raimi’s first feature-length attempt to experiment with suspense strategies: to utilise previously employed suspense techniques but also to surpass them by playing with and attempting to confound the expectations of audiences who consistently watched horror films. As Peter Hutchings has argued, those audiences who are familiar with the suspense or ‘startle’ patterns of horror tend to be aware of moments in a horror film where jumps and scares are likely to occur, leading to a sense of anticipation as the soundtrack goes quiet and audiences wait for someone or something to appear from the space outside of the frame. Throughout The Evil Dead, a wide range of suspense and startle strategies are employed as a means of playing games with this kind of audience, in some instances capitalising on audience anticipation of a scare and, in others, attempting to ‘get past’ the audience’s ‘defences’ by confounding expectations (Hutchings 2004: 140).

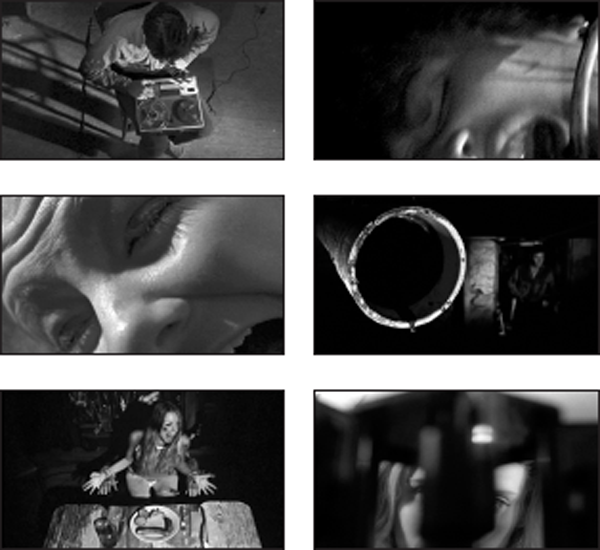

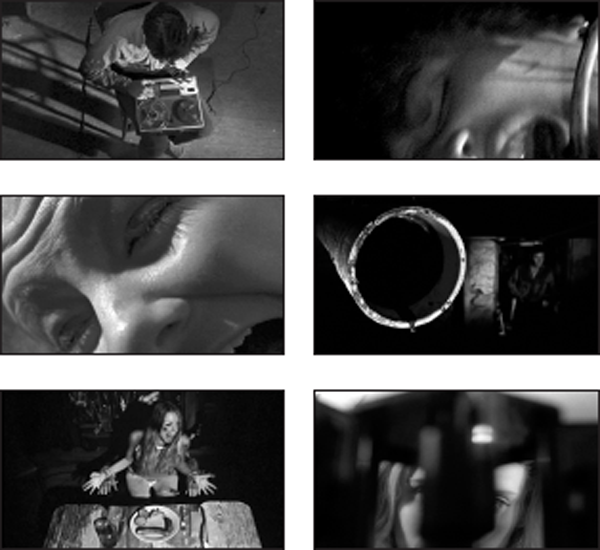

In the first half of the film, Raimi’s central suspense tool is the film’s most famous element: the ‘Shaky Cam’ point-of-view shots from the demon force’s perspective. The sequences where Cheryl and Shelley are attacked by the demon force are thus both preceded by a cut to this point-of-view shot, which moves closer to the cabin indicating that the demon force is about to strike and, consequently, preparing audiences for the resultant jumps and scares. Further to this, the audience is also put in a higher position of knowledge (generating suspense) in the middle of the sequence where the possessed Cheryl first attacks the other characters. As Cheryl falls to the floor (after the initial revelation that she has become possessed), the soundtrack goes quiet and we see a close-up shot of Cheryl reaching for a pencil on the floor. Thus, the film has prepared the audience for her subsequent pencil attack on the other characters.

Empty space in the frame, preparing audiences for the big scare

At other points in the film, however, the audience isn’t given this information prior to a scare but the formal patterns employed could potentially indicate, to the genre savvy audience, that a scare is about to occur. In some cases, an upcoming scare is signalled by empty space in the frame. For instance, in a sequence late in the film, the fact that the possessed Cheryl is about to appear at the window could be anticipated because of the fact that the shot of Ash is composed so that the empty window takes up the entire right side of the frame. In other instances, the quietness of the soundtrack could lead to the anticipation of a scare. Indeed, this strategy is repeated through all the main attack sequences in the film: when the possessed Cheryl and Shelley initially attack the other characters; when Cheryl tricks Ash into believing that she has returned to her normal state; when Linda attacks Ash as he prepares to bury her; when the cabin becomes possessed and Ash waits for the next attack; and when Cheryl and Scotty disintegrate at the end of the film. All of these sequences have a moment, in the middle of the onslaught, when the demons become inert, stop or fall to the ground and everything goes silent aside from the noise of crickets and the wind outside.21 This repeated use of a lull moment in the middle of sequences of attack thus also, potentially, prepares the audience for a scare.

While the use of certain conventions (involving sound and empty space) illustrates how the film capitalises on the expectations of the audience, Raimi also employs a number of strategies that hold the potential to undercut or rattle these expectations. Firstly, the film is filled with false startles, where the object causing the startle proves not to be dangerous. To give three examples: at two separate points in the film, Scotty appears from the left or right of the frame, making Ash jump; at two separate points in the film, Ash appears and grabs Cheryl, making her jump; and, at two separate points in the film, Raimi makes a sharp cut from a scary or creepy sequence to an everyday object (a blender and then an axe). Secondly, Raimi prolongs and sustains the tension in the sequence where Scotty searches for Shelley, by setting up a sense of expectation and then confounding it. Here, the music rises as Scotty approaches a cupboard which is then revealed to be empty, and then this strategy is repeated as the film cuts between Scotty’s point of view and a shot from behind the shower curtain, with Scotty pulling back the curtain to again find nothing there. Thirdly, Raimi uses false cues to try to throw the audience off-guard, with the threat then emerging from another part of the frame. For instance, after the two false scares in the Scotty search sequence, Scotty turns around and Shelley’s hand appears in front of him, while, in the sequence where the cabin has become possessed, Ash looks up thinking that the demon noises are coming from overhead and then is attacked by Cheryl through the wall behind him. All of these techniques have been employed in a range of other horror films, particularly in Carpenter’s Halloween, which uses a number of these strategies in order to initiate jumps and scares.22 However, what is particularly distinctive about The Evil Dead is the way in which Raimi builds, develops and interweaves these techniques throughout the film, encouraging audiences to anticipate scares because of the film’s previously established suspense patterns and then, suddenly, confounding expectations by breaking these patterns.

After some false cues, the threat emerges from another part of the frame

Further to this, the film plays with the conventions of the then nascent slasher film tradition in two other ways. As acknowledged by the filmmakers, the surviving character in this kind of film tends to be a woman and, as both Vera Dika and Carol Clover have noted, a woman whose watchfulness and lack of a boyfriend often distinguish her from the other characters, marking her ‘as a privileged character’ (Dika 1987: 90).23 The early section of The Evil Dead seems to conform to this sub-generic convention. Cheryl is clearly marked as the ‘outsider’ character from the beginning of the film, being given a close-up in the scene in the car on the way to the cabin and being the first to acknowledge that something is wrong. Consequently, when Cheryl is the first character to be singled out by the demonic force, attacked and possessed, the film seems to confound expectation. Furthermore, the fact that the survivor character turns out to be Ash also seems to overturn expectations. Aside from Cheryl, the most active character in the first half of the film is Scotty. He is the first to enter the cabin and we are introduced to the cabin as he explores it. And, when Cheryl becomes possessed and attacks the other characters, it is Scotty who acts by kicking Cheryl into the cellar and chaining up the trapdoor. The film then presents us with a close-up shot of Scotty’s troubled reaction, which also seems to suggest that he will be the dramatic focus of the rest of the film.

While Ash is focused on to some degree in the early sections of the film (in particular, in the sequences where he gives Linda a necklace and listens alone to the reel-to-reel tape), his evident cowardice seems to indicate that he will not fulfil the role of the characteristically brave and resourceful survivor character. However, this is not to suggest that Raimi entirely overturns these conventions. The fact that Shelley will be a victim rather than a survivor is signalled by her relative passivity and by the fact that, in line with slasher conventions, she is shown undressing (from the demon force’s perspective) prior to her attack.24 As with his utilisation of suspense patterns, Raimi seems to strike a fine balance, throughout the film, between conforming to some previously established conventions and relying on expectation in order to overturn others.

Raimi also plays with established suspense and shock patterns by fusing suspense with gore and comedy. As the film goes on, the main attack sequences can be seen to, gradually and incrementally, become more comedic (from the savage attack on Cheryl by the woods, to the combination of slapstick and close-ups of pain in Cheryl’s initial attack on the group, to the squelching sound effects that ac company the shots of Shelley’s dismembered body). While this is one way in which Raimi manages the shift from an atmospheric to a more fantastic and comedic tone in the latter stages of the film, the other relates to the parity between strategies of suspense and what Julian Hoxter calls ‘the attractive mechanisms of slapstick and the gag’ (1996: 71). In his essay on The Evil Dead and its relation to what has been termed the ‘splatstick’ tradition in horror films of the 1980s,25 Hoxter draws on Tom Gunning’s conception of ‘the mischief film’ and ‘the mischief gag’, as seen at work in the early Louis Lumière film, L’Arroseur Arrosé (1895). As Hoxter notes:

Gunning argues that the mischief film is constructed around the playing of a simple prank or ‘mischief gag’. The mischief gag operates in two stages … The first stage sets up the premise and foregrounds the victim of the prank (the gardener waters the plants and the small boy steps on the hose), often implying an outcome around the anticipation of which audience pleasure can cohere. The second stage presents the result of the prank (the gardener looks down the nozzle of his hose and is drenched when the boy removes his foot). (1996: 75)

There are a number of such ‘mischief gags’ throughout the second half of The Evil Dead (all of which involve Ash being pelted in the face with gore and blood). However, what is particularly noteworthy about these gags is the fact that they hold the potential to initiate similar kinds of audience anticipation as some of the straight suspense and startle sequences in the film. For instance, just prior to the commencement of the ‘mischief gags’ in the film, we are presented with a straight suspense sequence with a comedic edge. Here, Cheryl (from beneath the cellar trapdoor) tells Ash that she is not possessed anymore and that he should set her free. The soundtrack becomes quiet and we are then given a succession of shots from behind and to the side of Ash (as he approaches the cellar door), intercut with a shot of Ash from the point of view of Cheryl in the cellar. With the tension and the anticipation of a scare established, there is a brief pause before Cheryl’s hand bursts from the cellar and grabs Ash’s head while she cackles and mocks him. As the film goes on, we are then presented with a series of sequences that employ the same formal patterns in order to set up and initiate the anticipation of a mischief gag. For instance, in the film’s most memorable gag, Ash enters the cellar and the camera is placed behind him as he looks up at a dripping pipe. Then, as the sound of drips continues to be heard on the soundtrack, the camera slowly zooms towards the pipe and the film then cuts a number of times between a high-angle shot looking down on Ash (above the pipe) and the reverse shot, just behind Ash, looking up at the pipe. This sequence of shots therefore works, as in Gunning’s example and in the sequence where Ash comes towards Cheryl and the cellar door, to ‘set up the premise’ and ‘foreground the victim’ before the anticipated outcome occurs (which, in this case, is a flood of blood emerging from the pipe and hitting Ash in the face).

Setting up the premise, and foregrounding the victim

This segue from suspense and startle to mischief gag, in the film’s latter stages, can be seen to function in two ways. Firstly, the use of such mischief gags clearly relates to the game-playing between Raimi and the audience, as he continues to overturn expectations by dropping in a series of mischief gags whilst also continuing to weave in other straight suspense and startle sequences – for instance, Cheryl’s attacks on Ash from the window and behind the wall. Secondly, this connection between two conventions from separate genres or modes (suspenseful horror and slapstick comedy) illustrates Geoff King’s claim that the ‘offbeat or quirky quality’ of many independent genre films relates to their ability to ‘exist … in the space between familiar convention and more radical departure’ (2005: 167). On the one hand, this shift between suspense and comedy can serve to disorientate the viewer (contributing to the uneasy and demented character of the film as a whole), while, on the other, the fact that this shift is informed by familiar genre conventions (and the parity between suspense and mischief gags) means that audiences still have enough familiar genre signals and cues to interact and engage with the film’s narrative. However, another way in which the film achieves this balancing act is through the employment of techniques from the films of Romero and Hooper, which work to build another kind of bridge between elements from different subgenres of horror.

‘YOU MUST TASTE BLOOD TO BE A MAN’?: THE PULL BETWEEN CLOSENESS AND DISTANCE IN THE EVIL DEAD

In his influential study of the history of the horror film, Andrew Tudor argues that many horror films made from 1968 onwards can be distinguished from their generic predecessors because of their ‘paranoid’ perspective. For him, one of the key trends that illustrates this shift in perspective is the fact that, in the post-1968 horror film, ‘the known’ (encompassing social order, civilisation and normality) is presented as ‘far more precarious’ than the stable, strong representations of normality that characterised earlier horrors (1989: 215). In many respects, The Evil Dead exhibits this paranoid tendency, most prominently in terms of the visual perspectives offered on the five young characters during the course of the film. The sense that order, normality and stability are entirely ‘precarious’ is established from the very first shot of the film, which is presented not from the perspective of the human characters but from the point of view of the demon force moving across the water and towards the characters, as they travel by car to the cabin. The rest of this sequence then cross-cuts between three different sets of shots in order to create a suspense sequence with a false scare (cutting between the perspective of the force, the characters in the car and a truck travelling down the road, which, at the climax of the sequence, narrowly misses hitting the characters’ car). This opening sequence thus foregrounds the demon point-of-view shot (by introducing us to the film’s world through the use of this shot), and thus introduces us to one of the dominant perspectives from which we will observe these characters and their story.

Indeed, the film returns us to this shot continuously throughout the first half and this, potentially, prevents us from becoming entirely engaged with and attached to the characters. For example, the early section of the film includes a sweet and touching scene where Ash presents Linda with the gift of a necklace (accompanied by a series of close-ups of their eyes and gentle string music on the soundtrack). However, at the culmination of this sequence, the film returns us to the outside of the cabin, where we observe Ash and Linda from the distorted, wide-angle perspective of the demon force lurking outside, waiting to strike. As a consequence of these patterns, the fact that the characters are ultimately puppets and future victims of the demons is consistently emphasised, potentially pulling the viewer away from engaging with these characters on any other level. Admittedly, there is nothing particularly unusual or unconventional about this approach. Indeed, Carol Clover and Vera Dika have identified the strategy of beginning the film from the monster’s perspective as a convention employed in Halloween and a range of subsequent slasher and stalker films. For Dika, this ‘shifting’ pattern in the stalker film (where the film switches from shots from the killer’s point of view to scenes focused on the film’s characters, and then back again) can be related to the ‘gaming’ function of these types of films. For her, this shifting allows audiences to participate in the investigation and stalking of potential victims while also being able to ‘maintain a degree of moral distance’ from this stalking perspective, because we are not given ‘access’ to the ‘humanity’ of the killer in the way that we are with the film’s protagonist and his or her friends (1987: 89).

However, what perhaps distinguishes The Evil Dead is that these patterns are augmented by other techniques that seem to work to foreground the inevitability of the characters’ fate, and the sense that they are ultimately at the mercy of the demons. The first technique relates to the film’s narrative. After arriving at the cabin, the characters find the Book of the Dead and a reel-to-reel tape recorder in the cellar and, upon listening to it and playing the citation of the book’s incantations, the demonic force is shown to be unleashed. However, as has been pointed out by Bill Warren, this is to disregard the fact that the demonic force has already been shown to be rampant in the woods and (in the sequence where Cheryl draws the Book of the Dead) to be already present in the cabin (see 2000: 98). Warren argues that this is a flaw in the film’s narrative and, considering the piecemeal way in which the film’s script was put together, it’s possible that this is the case. However, this flaw does seem, whether intentionally or otherwise, to contribute to the sense that the possession and destruction of these characters is inevitable and that any and all of the characters’ actions and efforts are ultimately hopeless and futile.

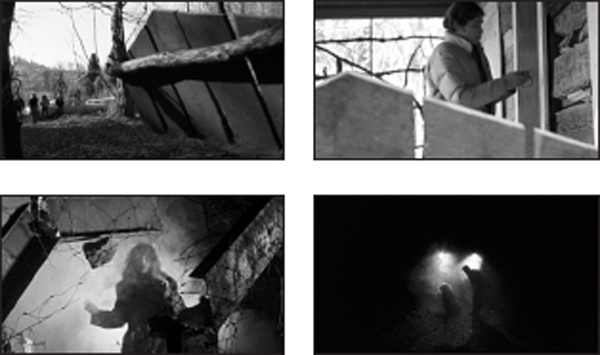

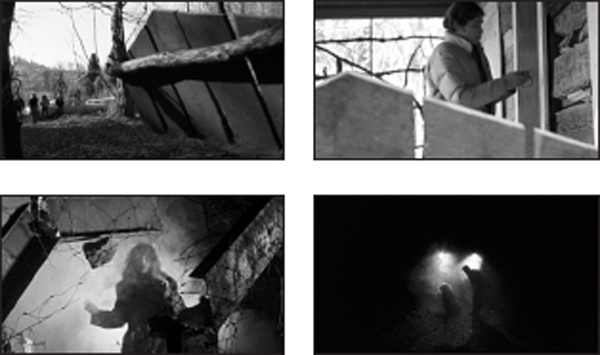

Shifting perspectives in The Evil Dead

The framing of characters by the camera and particular shot compositions also seem to contribute to this aura of inevitability and hopelessness, with some shots working to convey the sense that the characters are trapped and hemmed in by forces beyond their control. Firstly, characters are often filmed from very high or very low angles. This is particularly evident in the sequence, near the end of the film, where Ash emerges from the cellar to find that the entire cabin is possessed, but these shots also occur throughout the film, for example, from the high and low angles employed as Scotty first approaches the cabin and reaches for the keys, to the high-angle shot of Ash as he listens to the tape recorder. Secondly, and in contrast, the film also employs close-ups and extreme close-ups of faces at moments of attack. The infamous tree rape sequence is one example of this, with the majority of the rape being depicted via a series of close-ups of tree branches, parts of Cheryl’s body and her tormented face, and with no establishing or long shots being employed throughout. Others include the extreme close-ups of Linda and Scotty’s faces as they are attacked by possessed characters. Thirdly, a lot of the key scenes of tension are filmed with a handheld camera, with the sequence where Cheryl begins to panic after being attacked by the woods being a particularly effective example, in that the roving handheld camera contributes to the sense of terror and claustrophobia. Finally, the film is dotted with shots that are composed so that an object of some kind is positioned in front of the characters, in the extreme foreground. Some of the most striking examples of this are: the banging wooden swing-bench which dominates the right side of the frame as the characters arrive at the cabin; the clock pendulum which swings across the front of the frame in shots taken from the position of the clock looking out at a character; and the dripping pipe which dominates the left side of the frame as Ash leaves the cellar near the end of the film.

Many of these formal depictions of claustrophobia and entrapment seem to be inspired by the use of similar techniques in Night of the Living Dead and, most prominently, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. While, in Hooper’s film, the disorientating contrast between close and distanced shots is emphasised via camera zooms, Hooper also uses a handheld camera and cuts between high angles and extreme close-ups to convey a sense of helplessness and claustrophobia, particularly, and most famously, during the sequences where Sally Hardesty is tortured and tormented by the cannibal family at the climax of the film. Furthermore, both films also, occasionally, place objects in front of characters in particular shots (for instance, the dead armadillo in the foreground of one of the opening shots in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, which seems to suggest the inevitability of the characters’ fate, and the shot of the music box in front of Barbara’s face in an early sequence in Night of the Living Dead).

Claustrophobic shots from Raimi, Hooper and Romero

In terms of The Evil Dead, this roster of techniques contributes to the sense that the film is tapping into themes, ideas and perspectives most strongly associated with the horror fiction of H. P. Lovecraft. While it’s not clear that Lovecraft was a direct influence on Raimi when he first conceived of The Evil Dead, the film’s focus on Sumerian culture and the Sumerian Book of the Dead seems to connect with Lovecraft’s mythical book, the Necronomicon (and, indeed, Raimi explicitly named the book ‘the Necronomicon’ in Evil Dead II). Further to this, all three films in The Evil Dead trilogy have been identified by Julian Petley as examples of films that ‘draw on specifically Lovecraftian elements’ and ‘radiate a peculiarly and distinctly Lovecraftian aura’ (2007: 36). For Petley, The Evil Dead trilogy’s place in this category is primarily due to the films’ demon point-of-view shots, which, for him, ‘absolutely radiate a Lovecraftian sense of utterly malign and destructive power’ (2007: 46). However, Raimi’s use of high and low angles and objects in the foreground (which are associated, in some way, with the demon force) also seem to convey an ‘extremely powerful sense of mankind … at the mercy of forces utterly indifferent to its fate’,26 a perspective which, as Petley illustrates, is associated with the ‘pessimistic wider worldview’ put forward in Lovecraft’s fiction (2007: 47).

This Lovecraftian quality is particularly evident in two extremely effective and creepy sequences in The Evil Dead. The first occurs as the characters first approach the cabin. Here, as the car moves down the slope to the cabin, ominous music begins to play and we hear the sound of something banging. As the characters reach the cabin, they emerge from the car and we are given a shot of them standing, slightly out of focus, at the left side and at the back of the frame, while the source of the banging (a wooden swing-bench) is dominant at the right and foreground of the frame. As Scotty tentatively approaches the cabin, the film cuts to a shot at his side with the swing-bench in the foreground and, as he reaches towards the door, the swing-bench suddenly stops banging. The second sequence takes place after Ash attempts to drive Cheryl away from the cabin after she has been attacked. At the climax of the sequence, Cheryl is framed at a low angle with the destroyed bridge in front of her, in the foreground of the shot. Brass chords (which imbue the scene with a sense of doom and inevitability) begin to play, as Cheryl breaks down. As she screams and cries, the camera cranes upwards so that Ash and Cheryl are shown from a high angle, and her cries of ‘they’re not going to let us leave’ turn to an echo which carries over to the next shot. In both these cases, characters are shown to be dwarfed and at the mercy of something bigger than them and completely beyond their control. Furthermore, the demonic use of objects (in this case, the swing-bench and the bridge) to obstruct and intimidate the characters seems to relate to the Lovecraftian idea that the normal world, as we know it, is only a ‘surface’ which ‘provisionally and imperfectly … cover[s] … up the abyss’ of evil that exists beyond (Maurice Lévy quoted in Petley: 2007: 41).

Doom-laden shots in The Evil Dead

While this is perhaps being kind to the filmmakers, the film’s weak characterisation could also be related to its Lovecraftian qualities. Aside from the early scenes between Linda and Ash and some banter between Scotty and Cheryl, we learn very little, in The Evil Dead, about the characters’ backstories and relationships with each other, and this could be seen to dovetail with Lovecraft’s fascination with cosmic forces and his subsequent lack of interest in human characters. Indeed, the film’s ability to confound expectations, by signalling that certain characters will be the ‘survivor’ and then killing off these characters, seems to fit with the sense that rooting for any of these people will ultimately prove to be futile. As Andrew Tudor has argued, paranoid horror tends to suggest that ‘we have been cast loose in a world for which we no longer have any reliable maps’ (1989: 222), and this can be seen to be illustrated by the fact that the human characters that The Evil Dead invests in prove, ultimately, to be unreliable. The initial indications that Cheryl will be the ‘survivor’ are overturned when she is the first to become possessed and we begin to look at the other characters from her demon perspective; while any expectation that Scotty will be the chief survivor (after he acts purposefully and resourcefully to defend himself against the possessed Cheryl and Shelley) are thwarted when he ultimately abandons Ash and then returns to the cabin in a weak and wounded state.

However, this is to disregard the fact that, as potential survivors fall away and the tone of The Evil Dead becomes more comedic, the film shifts its focus more and more towards Ash’s perspective on what is occurring. As noted in the last chapter, for Within the Woods creator Mark Dutton and for a number of fan reviewers of the film on IMDb, the fallible and flawed nature of Ash as a character actually contributes to his likeability and to the sense that he is a normal everyday person. Indeed, the depiction of Ash as an inept but very likeable loser is in marked contrast to the more confident, almost caricatured version of Ash in the film’s sequels. It is therefore through this character that Raimi constructs a story arc of learning and awareness that mirrors Laurie Strode’s story in Halloween. As Vera Dika has argued, in relation to Halloween and other stalker films, the (usually female) survivor grows up during the course of the story, coming ‘to a new stage of awareness’ at the end of the film because she has had to ‘come to face the reality of death and violence’ (see 1987: 92–5). Raimi has acknowledged that this was also his intention, in that The Evil Dead could be read and experienced as a ‘rite of passage’, an approach which conformed to Raimi’s tongue-in-cheek statement that, in horror films of this kind, the main character ‘must taste blood to be a man’ (in Warren 2000: 44).27

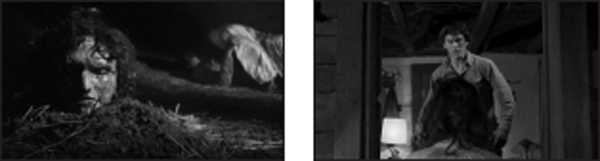

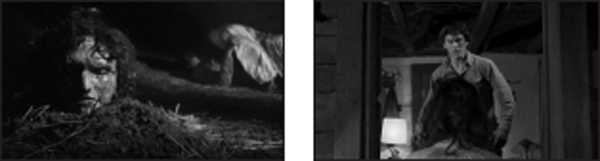

In The Evil Dead, Ash therefore goes on this gradual journey of awareness, as he struggles with the fact that his friends, and particularly his girlfriend, are now demons and have to be destroyed. Raimi foregrounds this struggle as the film goes on, through a number of moments that punctuate the increasingly gory and insane acts of violence that occur across the second half of the film. Thus, in the excessively gory sequence where Shelley is attacked and dismembered, Scotty compels Ash to ‘hit her, hit it!’ as Ash remains frozen to the spot. Here, Ash’s failure and ineptitude is emphasised as, in one shot, Shelley is stabbed by Scotty and then falls to the ground, revealing a petrified Ash cowering in the background. After Scotty’s departure from the cabin, the gory battles with the remaining demons are punctuated with a series of moments that continue to focus on Ash’s struggle to accept the need to kill his former friends. In one sequence, Ash is shown carrying Linda to a workshed, and we are then treated to a quickly edited series of shots that document the process of Ash chaining her to the workbench and obtaining a chainsaw.28 As he’s about to switch on the saw, the soundtrack plays the same music used in the earlier sequence where he gave Linda the necklace, the editing pace slows and Ash admits defeat. Then, after he has decapitated and buried Linda, we are given an insight into Ash’s thoughts through a sound montage of pieces of dialogue from the film, including the lines ‘hit her, hit it!’ and ‘I love you’. However, after hearing Linda’s demon giggle, he states, ‘shut up Linda’ and proceeds to purposefully load a gun with bullets.

Emphasising Ash’s cowardice and his rite of passage journey

As should be evident, what these series of moments suggest is that Ash’s particular journey is about accepting death and violence but also about becoming (as Raimi’s horror film rule suggests) a man, who has to accept the necessity of thinking, first and foremost, about himself and be willing to defend himself through whatever means necessary. Indeed, and as I will go on to show in the last section of the chapter, the second half of The Evil Dead can be read not only as a depiction of Ash’s personal nightmare but also, in the sense that his primary opponents are possessed women, a particularly male nightmare. The sequence where Shelley becomes possessed and attacks Ash and Scotty seems to signal that the rest of the film will play out in this way. Here, Shelley’s slow death (after she has been stabbed) is interspersed with close-up shots of the two incredulous men witnessing her slow and gory disintegration. Subsequent to their dismemberment and burial of Shelley, Scotty then abandons Ash, after noting that Linda is Ash’s problem because she is his girlfriend and he has to look after her. The baton is therefore passed, during the course of this sequence, from one male protagonist to another.

By the end of the film, Ash also seems to have adopted Scotty’s attitude, in that, in order to survive, he has had to come to terms with the need to put himself first, to reject the ideas of romantic love that he has associated with Linda, and to use violence against anyone who threatens him (including his girlfriend). For Dika, the fact that this also seems to be the message of many stalker films (in the sense that aggressive action is seen to be the only way to face reality and become an adult) suggests that the ideological perspectives of The Evil Dead, Halloween and other stalker films are all ultimately quite conservative.29 However, after engaging us in Ash’s journey and struggle throughout the second half of the film, Raimi succeeds in pulling the rug out from under the viewer one more time. As Ash rises victorious from the melting remains of Scotty and Cheryl, music swells on the soundtrack and Ash leaves the cabin to look at the sun rising, in a sequence which seems to signal that all has returned to normal and that the battle with the demon force is over. Suddenly and disorientatingly, the film cuts to a close-up of a leaf somewhere in the woods and we are placed back with the demon force, as it bowls through the woods and launches itself straight into Ash’s face.

This end sequence seems to return us, then, to a Lovecraftian perspective on the film’s characters, suggesting, once again, the futility of Ash’s journey of awareness and emphasising the fact that the demons are far bigger and more powerful than the characters, their struggles and the story of the film as a whole. As a consequence, the film ultimately removes the last secure purchase audiences may have had on the human characters and their predicament, causing a last scare but also, potentially, disorientation as the film shifts back to the ferocious, pessimistic worldview of its demons. However, if this is one way in which the film obstructs the audience’s ability to engage with Ash, then another relates to its characterisation of the possessed humans as perverse and mischievous. The extent to which this focus on perversity and humour adds to the film’s creepy and grotesque quality, and complicates the idea that the film is entirely influenced by Lovecraft, will thus be the focus of the next and last section of this chapter.

‘WHY ARE YOU TORTURING ME LIKE THIS?’: ASH’S BATTLE AGAINST RAIMI AND THE LADIES OF THE EVIL DEAD

While Ash’s story arc in The Evil Dead can be seen as linear (charting his gradual acceptance of ‘the reality of death and violence’), this narrative trajectory is distinctly undercut, in the film’s second half, by the demons’ increasingly comedic torture of this character. This aspect of the film equates it much more with The Texas Chain Saw Massacre than Halloween and other subsequent stalker or slasher films. Like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’s Sally Hardesty, Ash is pitted against the demons in a battle for his sanity, and, consequently, the spectacular sequences in the second half of the film focus as much on the torture of Ash as they do on gory deaths. As a result, the possessed humans are presented as extremely ambiguous characters. While they are as aggressive and violent as the demon point-of-view shots suggest them to be, the key means by which they torture Ash and attempt to drive him insane is through a mischievous, demented form of comedy and slapstick.

In many respects, this seems to draw on the same kind of disturbing and disorientating comedy employed in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, most prominently in that film’s infamous dinner scene. As in this scene, the monsters’ glee in The Evil Dead increases as Ash becomes more and more woeful and disturbed. The key source of this glee, within the story, is the demon Cheryl, who serves as a kind of cheerleader for the torture enacted by the other demons. Throughout the sequences where Ash and Scotty are manipulated and tortured by Shelley and Linda, the film continually returns to close-ups of Cheryl peering out from the cellar door, either cackling in approval or banging the cellar door excitedly. Furthermore, we also continually hear Cheryl cackling on the soundtrack as surviving characters cry out in despair and woe, most prominently when we witness Shelley’s disturbed reaction from Cheryl’s point of view in the cellar and, later in the film, when Cheryl cackles at Ash’s attempt to reassure the wounded Scotty.

Within the context of the story, these demons are also, inadvertently, responsible for the ‘mischief gags’ enacted upon Ash in the second half of the film, with the most memorable instance of this being the sequence where Linda attacks Ash as he attempts to bury her. Here, as in the dripping pipe example discussed earlier, anticipation is initiated by a series of shots that indicate the possible outcome of the gag. We are presented with a shot of Linda’s decapitated body, then a shot of Linda’s head hitting the ground while her headless torso writhes on top of Ash, then a shot of Ash’s face with Linda’s headless shoulders in the foreground, and then, finally, we get the comic pay-off as Ash’s face is pelted with blood from Linda’s neck. To top it all off, we are then treated to a shot of Linda’s head gleefully moaning as Ash is messily violated in the background. In some respects, these gags could be seen to undercut The Evil Dead’s potential to horrify, scare and disturb, turning the film into an out-and-out slapstick comedy (as some fans claim is the case with the film’s sequels). However, there are a number of ways in which the film works to maintain the horror throughout its second half.

Firstly, and importantly, there is a distinct difference between Bruce Campbell’s interaction with these gags in the first film and in the film’s two sequels. In the sequels, Campbell tends to work with the comedy rather than against it, crossing his eyes, enacting comedic falls and playing a character who is as mischievous and cartoon-like as the demons who he is fighting against. In the first film, by contrast, he continues to play the character as a normal, frightened, disturbed man throughout all the sequences where he is manipulated by the demons and turned into a comedy straight-man for their evil gags. As is the case with Sally in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Ash therefore remains primarily a horror (rather than a comedy) character throughout these sequences, becoming visibly more confused and disturbed as the demons laugh at his woe and fright and, consequently, keeping the film’s comedic elements in check.30 Secondly, the composition of shots in two of the most comedic sequences involving Linda remain consistent with earlier, non-comedic shot compositions in that they involve an object being placed in the foreground, in front of Ash. The shot where the decapitated Linda is shown writhing on Ash’s body places Linda’s decapitated head in the foreground; and the shot where Ash is shown punching Linda in the face, repeatedly and in time to the music, is framed so that Linda is in the foreground of the shot with her back to the camera. It could be argued that the composition of these shots is informed by, and is working for, the comedy in both these sequences (in the sense that they are distancing us from Ash and Linda as characters, so that we can enjoy the gag and treat them as bungling comedy fall-guys rather than characters in a horror film). However, whether this was intentional on the part of Raimi or not, the composition of these shots remains consistent with the formal patterns set up earlier in the film, and their associations with entrapment and the control of these characters by malevolent demons (elements which could serve to undercut the evident comedy and humour in these sequences).

Balancing comedy and horror through shot composition

However, perhaps the major way in which these comedic sequences maintain a disturbing edge relates to the most distinctive aspect of these scenes: the fact that the principal demon torturers are all female. This seems to connect to the fact that, as acknowledged by John Kenneth Muir and the film’s cinematographer Tim Philo, the second half of The Evil Dead seems to play out as Ash’s nightmare (see Muir 2004: 67). Consequently, the demons clearly manipulate and torture Ash by playing on his key weakness: his earlier established belief in romantic love.31 This focus on the possession of female characters is, again, not particularly distinctive or unusual within the horror genre. Carol Clover has argued that ‘the portals of occult horror are almost invariably women’ (1992: 70–1), and that such films often employ ‘“dual focus” narratives’ which centre as much on ‘the story of male crisis’ as the ‘story of female possession’ (1992: 70). However, what is, potentially, pleasurable about the torture of Ash (and Scotty) in The Evil Dead is not just the fact that it’s so comedic and manic, but also that the demonic possession of the three female characters allows them to poke fun at and humiliate their male counterparts.

This, like the end of the film, seems to undercut Ash’s journey-narrative arc, and the focus, in the early stages of the film and in Scotty’s later conversation with Ash, on the men looking after the female characters. On becoming possessed, Shelley changes from a frightened, passive woman into a sexually manipulative character, talking about the burning of her ‘pretty flesh’ as she moves towards a petrified Scotty. In contrast, the previously aggressive and macho Scotty proves himself to be the most pathetic and least aggressive demon character, lurching around the room like a zombie and then quickly being dispatched by Ash. This overturning of the need for the men to protect the female characters is also evident in the sequence that occurs after Ash takes Linda to the workshed but is unable to kill her. After breaking down, Ash picks up Linda in her flowing white nightgown and takes her outside, carrying her in his arms. Here, we are presented with images that (as John Kenneth Muir and Raimi and Tapert have acknowledged) are incredibly gothic (see Muir 2004: 67), drawing, in particular, on the kind of imagery employed in such Hammer Horror films as Dracula (1958) and The Mummy (1959).32 However, this gothic and romantic image is eventually overturned by the incredibly ridiculous and perverse sequence where Linda is decapitated after Ash attempts to bury her, with her headless torso then writhing sexually on top of Ash’s body as her decapitated head moans with pleasure.

As well as serving as the ultimate torture for Ash (in that this perverse version of sex completely overturns the earlier chaste and sweetly romantic relationship that he is shown to have with Linda), this sequence also taps into characteristics or tropes that have been identified as dominant in many post-1968 horror films and, indeed, in a number of key cult films. On the one hand, it suggests how the film, like other horrors such as The Exorcist or Carrie, projects ‘horror and evil on to women and their sexuality’ (Robin Wood quoted in Hutchings 2004: 187). However, this sequence can also be related to Gaylyn Studlar’s claim that many independently produced, taboo-busting cult films, such as Pink Flamingos (1972) and The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), feature ‘the de-eroticised visual treatment of varied sexual acts’ (1991: 141). The completely de-eroticised version of sex depicted in the Linda burial sequence can be seen as gleeful and irreverent, allowing audiences to enjoy the havoc that the mischievous Linda wreaks as she humiliates and punishes Ash.

Evoking gothic imagery

Indeed, there is something distinctly carnivalesque about this sequence. In their discussion of the carnivalesque aspects of the films of John Waters and Lloyd Kaufman, Xavier Mendik and Steven Jay Schneider note that ‘for Bakhtin, the social dimension of carnival practices was marked through the principle of a “world turned upside down”’ and that, consequently, ‘the carnivalesque emphasises the body that is overwhelmed by its own gestures and secretions … that is dominated by libido rather than rational thought … that provokes both laughter and unease in the viewing spectator’ (2002: 208). In this respect, the Linda burial sequence in The Evil Dead works effectively because it turns Ash’s naïve ideas about romantic love ‘upside down’ by foregrounding the gross biology of the human body. This sequence thus seems to tap into the connections made between femininity, human biology, perverse sexuality and irrationality in Mikhail Bakhtin’s theories of the carnivalesque and in many modern horror films,33 in order to augment the sense that the demons are archaic, pre-modern creatures who are attempting to turn the normal world ‘upside down’ and send Ash towards insanity. As a consequence, this sequence can be enjoyed for its comedy, its taboo-breaching depiction of sex, its irrationality and the fact that these demonic women are turning the world ‘upside down’ by torturing their former boyfriends.

However, the sequence also, in its own comedic way, feeds into the film’s more malevolent perspective on the characters – that, ultimately, they are all puppets at the mercy of a powerful demon force. This not only relates to the fact that sex is being mocked and derided in this sequence, but also death as well. As Philip Brophy has argued, in his influential article on the modern horror film, the ‘awkward and messy depiction of … death’, in such films as The Evil Dead and Friday the 13th, can work to make gory death scenes seem as comic as they are horrific (1986: 12). For Barry Keith Grant, ‘this uneasy combination of tones’ in films of this kind ‘has the potential to generate a rich and disturbing tension in the viewer’ (2000: 21), and this is augmented, in The Evil Dead, by the fact that sequences like the Linda burial scene and the later ‘meltdown’ scene (where Ash is continually splatted in the face as the remaining two demons decompose and explode) are interwoven with more serious scenes which focus on Ash’s inner turmoil. As a consequence, the film’s disorientating and disturbing quality can be related to the way in which it uses mischief gags and perverse, carnivalesque comedy to enhance the film’s more malevolent perspective, a perspective from which all human life (including romance and sex) is meaningless and all the characters, including Ash, are ultimately at the mercy of the abyss of irrational evil that the demons represent in the film.34 If comedy is often based on cruelty or evilness, then Raimi’s linking together of Lovecraftian elements and carnivalesque comedy brings this out forcefully and memorably in the film, imbuing many of the more slapstick scenes with a pessimistic, disturbing undercurrent.

Looking at the film from a different perspective, its disorientating quality can also be related to its highly ambivalent treatment of women. As a consequence of the fact that the second half of the film plays out as Ash’s nightmare, the film’s female characters have an active and substantial role in the narrative. In contrast to the kind of female slasher victims who, Dika argues, ‘never perform narratively significant actions’ (1987: 89), Cheryl, Linda and Shelley play key roles in the film through their consistent torture of Ash. The havoc wrought by these female demons on the male characters can thus serve as a potentially pleasurable experience for audiences and also, for many Evil Dead fans, one of the most memorable aspects of the film. If nothing else, the sustained focus on these female characters, throughout the film’s running time, has allowed the three actresses who played these roles (Ellen Sandweiss, Betsy Baker and Teresa Tilly) to join up as the self-proclaimed ‘Ladies of the Evil Dead’ and tour fan conventions, with, as Baker (2007) has acknowledged, many fans informing her that her performance as the possessed Linda was, for them, one of the creepiest and scariest aspects of the film.

More problematically, the pleasure that can be gained from the film’s active, mischievous possessed women is, inevitably, complicated by its depictions of violence and, in one famous case, sexual violence against women. As Peter Hutchings has noted, potential audience pleasure in the chaos created by such aggressive female horror characters as Carrie, The Exorcist’s Regan and Nola in The Brood (1979) is counterbalanced by the fact that this therefore underscores, within the narrative, the notion that ‘women existing apart from male authority are dangerous’ and that ‘defensive male violence against them is therefore justifiable’ (2004: 188). In line with The Evil Dead’s focus on his rite of passage journey, Ash finally wins his battle against the demons only by committing violence against the women who are torturing him. Consequently, the female characters are as much the butt of some of the slapstick and gross humour in the film as Ash and Scotty are. Indeed, the fact that the demon Linda moans pleasurably as she is decapitated and continues to giggle as she is punched repeatedly in the face adds to the disturbing, ambiguous nature of these scenes, as both women and men are slapped around in cartoon style. Perhaps more problematically, the more comic treatment of sex, death, gore and violence in these later sequences seems to jar when compared with the tree rape scene from earlier in the film. While this scene has been considered as laughable by some Evil Dead reviewers on IMDb, because of the fact that the premise of the sequence is so fantastical and ridiculous, the claustrophobic way in which this sequence was filmed and its particularly savage denouement (as a tree branch is seen to penetrate Cheryl) gives it a harrowing and real quality which contrasts with the more fantastical, comic violence meted out to Ash and the female demons later in the film.

This tension in the film seems to relate to what Barry Keith Grant and Gaylyn Studlar have identified as being a key characteristic of many cult films (particularly the ‘midnight movie’ variant): their ideological ambiguity. Perhaps the fact that the evil dead was assembled using a patchwork method (combining and fusing elements, sequences and ideas from a range of different horror traditions) meant that, inevitably, the fusing of these ideas would lead the film to not only be disorientating and disturbing but also ideologically inconsistent and ambiguous. Indeed, this illustrates Eco’s claim that collating together different generic or textual elements can lead to an inconsistent film, which focuses not on ‘one central idea but many’ (2008: 68). From a more positive perspective, this ambiguity enables audiences to, potentially, take pleasure in the female demons’ manic torture while also rooting for the likeable, fallible Ash at different moments, or even at the same moment, in the film.

More broadly, another aspect of the film allows audiences of the evil dead to engage in another potential pleasure and adopt a further perspective on the film’s characters and story: the foregrounding of the perspective of Sam Raimi himself. As has been acknowledged by many writers on cult, one element that frequently characterises cult films is their tendency to be self-reflexive or, in Hutchings’ words, to ‘invite … an audience to think about the materials out of which films are fashioned’ (2004: 129).35 The suspense games that Raimi plays with the audience is one way in which the evil dead seems to draw attention, self-consciously, to its status as a horror film, while another is the positioning of a torn poster of The Hills Have Eyes at the centre of the frame in the early scene in the film when Ash and Scotty first venture into the cellar.36

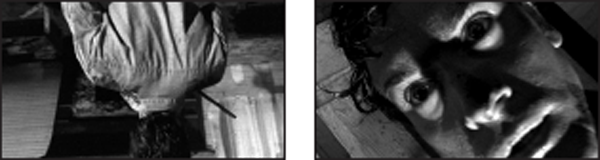

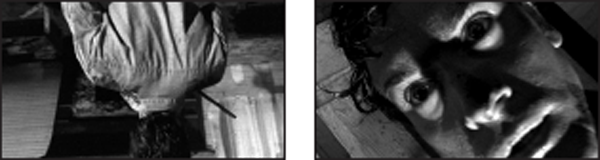

However, the key sequence which seems to foreground the evil dead’s status as a film is also the one which, paradoxically, is most focused on Ash’s subjective experience of the unfolding horror: the sequence where Ash emerges from the cellar to find that the entire cabin has become possessed. While, up to this point in the film, canted frames are only occasionally employed, this entire sequence is packed with frames canted at a variety of angles and shots of Ash taken from above and below. As Geoff King has noted, these formal strategies are motivated by the narrative in that, along with the close-ups of Ash and the noise of his heartbeat on the soundtrack, they clearly represent either ‘the presence of the invisible evil force’ in the cabin or ‘its effects on Ash’ (2005: 151). Nevertheless, and at the same time, they also seem to draw attention to the presence of the camera throughout this sequence. As Kristin Thompson has argued, ‘every stylistic element [in a film] may serve at once to contribute to the narrative and to distract our perception from it’ (1977: 57), and this is particularly the case with the sequence’s two most distinctive uses of camera movement and sound effects.

After Ash has re-entered the cabin, and we have been treated to a succession of shots of him from a variety of different angles, the film cuts to a shot of Ash filmed from an upside down position and, as the camera soars over his head coming to rest the right way up and in front of him, the soundtrack lets out what Geoff King describes as a ‘woozy-roaring sound shifting from high to low pitch’ (2005: 153). Then, slightly later in the sequence, Ash is filmed from high up as he clutches a gun and searches for the demons. As the camera follows Ash, it dollies from right to left and wooden beams appear in front of the camera as it moves. As the camera crosses over each beam, it makes a low, squeaking sound which seems to represent not only the presence of the demonic force but also the sound of the camera moving across the beams. As a result, such sound effects could be seen to work to ‘contribute to the narrative’ and ‘distract our perception from it’, drawing attention, as Geoff King notes, to ‘the hyperbolic nature of the camerawork’ (2005: 152) and, by extension, the stylistic inventiveness of the man behind the camera.37 Furthermore, the fact that, as is well documented, Raimi always took great pleasure in torturing Bruce Campbell, from their early short films and onwards, adds an extra layer of potential meaning and pleasure to this sequence, in the sense that Raimi and the camera are explicitly aligned with the demonic force at these moments.38

Raimi foregrounding the camera, and focusing on Ash’s terror

As noted in the previous chapter, many fan reviewers of the evil dead on IMDb appreciated the film because they could ‘feel the presence’ of Raimi behind the camera (Super_ Fu_Manchu, London, 9 February 2004). The techniques employed in the possessed cabin sequence could be seen to contribute to this characteristic of the evil dead, but what is also noteworthy is the fact that Raimi draws attention to the camera and himself in the same sequence where we are also presented with the most subjective vision of Ash’s torment and terror. By emphasising Ash’s terror at the same moment that he foregrounds himself as what Muir calls the ‘master manipulator’ of the film and its horrors (2004: 64), Raimi allows this self-consciousness to dovetail nicely with the other disorientating patterns and perspectives in the film. As a consequence, these strategies still contribute to the film’s overall rollercoaster quality. By presenting us with a variety of perspectives on the action at different moments and, at times, at the same moment (the perspective of Ash, of the demonic force, of the mischievous female demons, of the camera and Raimi himself), Raimi effectively conveys the claustrophobia and paranoia that permeates the entire film and the sense that the onslaught on the human characters is coming from all sides and from all perspectives.

What seems key to the effectiveness of the evil dead, then, is the fact that it can be enjoyed in multiple ways (as a stylistic tour-de-force, an interactive game of suspense, an inventory of key elements from the history of the horror film and an over-the-top comedic gorefest), but that all of these elements also cohere, overlap and clash against each other in order to imbue the film with a disturbing, disorientating quality that has been identified and appreciated by many of its fans. Raimi’s close scrutiny of many classic and commercially successful horror films appears to have enabled him to identify the horror genre’s many and varied capacities and capabilities, in particular, the ability to combine humour and horror in disturbing ways (as in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre) and, as Geoff King identifies, the potential to use a supernatural premise as a means to experiment with the camera.39 Throughout the evil dead, Raimi mines these creative possibilities and fuses them together, in order to create a film that is an enjoyable rollercoaster experience and an effective vehicle for his idiosyncratic, uniquely disturbing approach to horror. Indeed, it is this balance which appears to have allowed the evil dead to be appreciated by its critical supporters and fans as an audacious and surreal but also effectively scary film, whose category-defying qualities and appeals allow it, for them, to surpass many other contemporary horrors.