The Mack Sennett Studios in the 1910s.

The Early Years

ALICE HOWELL WAS BORN ALICE FLORENCE CLARK IN NEW YORK ON May 20, 1886; her mother, Rosea (or Rose) Smith, was born in New London, Connecticut, and her father, John Clark, in Ireland. Both parents were Catholic. In later years, on her marriage certificate and on her daughter’s birth certificate, Alice Howell would give her real name as Alice Florence McGuinness; she also took two years off her age, generally claiming to have been born in 1888. Alice was not the first child with that name to be born to the Clarks; as was not uncommon, when a first child, Alice (born in July 1885), died prematurely at twelve days old, the second child was given the same name. There was also a younger son, George, born on June 8, 1888. Within a dozen years, Alice’s mother was a widow, supporting two children in Manhattan.1

In interviews, the comedienne always claimed Irish ancestry, an assertion that was guaranteed to be popular with a largely immigrant, often Irish, audience. “Irish by descent and American by birth—make a combination that cannot be beaten,” as one fan magazine pointed out.2

At high school in New York, Alice proved herself to be a competent sportswoman and acrobat. She was also an accomplished swimmer and proved adept at pratfalls, an ability unusual for a woman and one which would stand her in good stead when she embarked on a screen career. Alice joined the basketball team along with a friend, a White Russian who would later live with her brother, painter Dimitri Romanovsky (1887–1971) at the art colony in Old Lyme, Connecticut.

Alice Clark married Benjamin Vincent Shevlin, also a Catholic, in 1904, and a daughter, Julia Rose Shevlin, who was always called Yvonne, was born in Chicago the following year, on July 30, 1905. “His parents had money,” Yvonne told me, “and they put him in the saloon business twice. My mother loved it, because she was a good cook. And in those days, they [the patrons] went there for a couple of drinks and they could eat all they wanted.”3 Alice and her husband separated (he died shortly thereafter) and she left her daughter in the care of her grandmother and later family friends, Jack and Millie Kennedy, while embarking on a stage career despite having had no previous experience in the field. It was strictly a matter of making a living.

Jack Kennedy was a drummer playing in orchestras on the Keith-Orpheum vaudeville circuit and his wife was a ballet dancer. When they were working in vaudeville and it was not practical to have Yvonne with them, she was sent to South Carolina to say with Jack’s father who was chief of police in Greenville. The couple proved more reliable than Alice’s mother who sold Yvonne for fifty dollars. “She said, you can have her,” claims Yvonne. “Of course, when my mother came home she bought me back.”4

Little is known of Alice Howell’s work on the stage. Contemporary sources indicate that she was appearing in musical comedy and burlesque from 1907 onwards. As some point, she toured with the De Wolf Hopper Company. “Hedda Hopper was in the show with her,” recalls Yvonne, “and De Wolf Hopper wanted to marry anybody. But the only one who would listen to reason was Hedda Hopper. She was climbing up the ladder.” Alice Clark met and married a vaudevillian named Dick Smith, and in 1910, the couple adopted the name of Howell and Howell when a vaudeville act with that name failed to show up for an engagement. “He had no talent at all,” said Yvonne disparagingly of her stepfather. But the couple’s comedy act lasted, if not prospered, for some years. There is no record of what the act consisted of, although it is assumed that basically it was physical comedy without dialogue, and while the couple may not have been headliners or made any lasting impact, it is very obvious that the years in vaudeville helped Alice Howell to “tune” her comic timing and to understand how an audience might react to a gesture, a raised eyebrow, the lifting of a hand. She could have had no better training as a comedienne.

Dick Smith was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on September 17, 1886, and virtually nothing is known of his early life. He was to have a substantial if undistinguished career in film, working as an actor, writer, and director, with his most famous contribution to the history of the motion picture being the direction of a film that was never released and is now believed lost. A two-reel comedy, Humor Risk, was filmed in all probability at a studio in Hudson Heights, New York, in 1921, with its title a burlesque of the Fannie Hurst novel Humoresque (filmed the previous year), and its non-Humoresque storyline provided by Jo Swerling. What makes the film important is not Smith’s involvement, but its leading players, Chico, Groucho, Harpo, and Zeppo Marx, making their screen debut.5

The Mack Sennett Studios in the 1910s.

With no air-conditioned theatres, vaudeville basically closed down in the hot weather, and legend has it that in the summer of 1913, Dick Smith happened to meet Mack Sennett on Broadway. The two had apparently appeared together on stage—Yvonne claimed they had been in a quartet together—and Sennett suggested that Smith and his wife might consider working in films. Mack Sennett had entered films with the American Biograph Company in 1908 and founded his own producing entity, the Keystone Comedy Company, in 1912. In the fall of that year, he moved the company to Los Angeles, and it would seem that if a meeting between Smith and Sennett actually took place, it was in the summer of 1912 and not 1913.6

Alice Howell and Dick Smith did not immediately respond to Sennett’s invitation, but came West in 1913, after Dick Smith was incorrectly diagnosed with tuberculosis. The couple stopped off for five days in Arizona, and considered settling there, but found it uninteresting—“the loneliest, most obsolete, terrible place,” according to Yvonne—and decided to move on to California.

During this time and later, Alice Howell devoted herself to her husband, caring for him when it seemed he had tuberculosis and nursing him when it was later diagnosed as emphysema. According to her daughter, Smith was not popular with his fellow entertainers. “He was just for himself. Just a selfish man. And my mother spoiled him by taking wonderful care of him,” said Yvonne. “She made a lot of money. He became a writer. He stuttered and he couldn’t hear and he couldn’t speak,” she laughed, “couldn’t do anything. Well, the one thing he excelled at—he was on the make for anybody.”

Once in Los Angeles, Howell and Smith found employment with Sennett at his Edendale studios, in what is now the Echo Park area of the city. The two became part of a company which provided, what previous writers have concluded, “a touch of vulgarity which offended sensitive and educated people … exactly what appealed to the average moviegoer of 1913.”7 Howell would generally work alone, while Smith separately would often play effeminate or “nance” characters. His talent in this area is apparent from some of his mannerisms and gestures in the Reelcraft comedy Cinderella Cinders.

As Alice recalled, “It was up to me to find something that would take care of both of us and I got a job as an extra in the Keystone Company. Sometimes I made $6 a week, and sometimes it went up to $9. It’s not easy to be funny on $6 a week with an invalid at home, but I had to do it.”8

In a 1917 interview with the New Jersey Tribune, she modestly commented,

I was glad to do any kind of work and I have not forgotten how it feels to stand in line waiting for a chance to do extra work. I wanted the money so badly that I offered to wear any eccentric sort of make-up or take any chance so long as there was a pay check at the end of the week.

I often felt then like the down-trodden, put upon, much abused slaveys that I struggle to portray humorously today. Most of my scenes are broad farce of course, but when I get an opportunity I try to register faithfully the character of such a girl.9

Daughter Yvonne confirms: “It wasn’t glamorous at all. It was just a bunch of out-of-work actors.”

In 1920, Alice Howell expressed a desire—as far as one can ascertain, not achieved—to move on from extreme comedy roles, and, at the same time, discussed the beginnings of her career at Sennett. After explaining that her performances were “exaggerated” but not “rough,” she continued,

I’m trying to get away from the more violent comedy roles with which I have always been identified. It is not easy to do this, especially when one has established a reputation for rough-and-tumble comedy.

It started about five years ago at the Mack Sennett studio. I was one of the mob in a police raid. Suddenly I threw myself into the thick of the fray. The other women drew back. We all had on evening gowns and the girls didn’t want to spoil them. I had no scruples. I fell downstairs and literally wiped up the floor with my gown. Mack Sennett was impressed and decided to give me a chance. Ever since then I have been expected to inject a lot of slapstick into my performances.10

The couple rented a small house on Alessandro Street, close enough to the studio that Alice could walk to work. While she retained her vaudeville title of Howell, Dick Smith reverted back to his original name. The comedienne claimed that her first appearance in a Keystone film was in Beans to Billions in January 1914.11 There is, however, no Keystone film of that title or with a similar title. (But there is a 1915 L-Ko comedy with a similar title.)

Charlie Chaplin had yet to join the company, but while Alice may have predated his debut there, her earliest documented appearances are in the former’s comedies, beginning with Caught in a Cabaret, released in April 1914. In all, Alice had small roles in at least seven of Chaplin’s Keystone comedies, together with the feature-length Tillie’s Punctured Romance.

The most prominent of Alice’s appearances at Keystone in support of Chaplin is in Laughing Gas, released in July 1914, and which is the first comedy both written and directed by the comic genius. She plays Mrs. Pain, the wife of dentist Fritz Schade, accosted by Chaplin, who pulls off her dress as she tries to escape his attention. At the film’s close, Chaplin is knocked down by her, and Alice, in turn, collapses on a couch. The energetic quality of the performance is indicative of what Alice Howell was later to accomplish, and the physical comedy demanded of her is not of the variety asked of other Keystone actresses such as Minta Durfee. Alice is stylishly dressed, although she is required to display her bloomers to Chaplin and the viewing audience.

Laughing Gas contains a strong sadistic streak, and both in terms of its basic storyline and approach to women, it has been compared to W. C. Fields’s 1932 short subject The Dentist. There are only two known contemporary reviews of the film, neither of which make reference to the Alice Howell character; the British trade paper The Bioscope (November 26, 1914) hailed the film as “an uproarious farce of a kind which is likely to create unrestrained mirth for its particular class of audience.”

Tillie’s Punctured Romance is the first Chaplin feature-length production, although its nominal star is Marie Dressler, then at the height of her fame as a theatrical entertainer. Released in November 1914, the film provides Alice Howell and Dick Smith with a brief comedic sequence as guests at a party. Neither received screen credit for their work.

The first, and perhaps only, Keystone production in which Alice Howell has a starring role is Shot in the Excitement, released in October 1914. Here, she demonstrates her willingness to appear in unattractive guise as a young lady with two would-be suitors in the persons of Al St. John and Rube Miller.

The comedienne is there in the opening scene, helping her father whitewash the fence until distracted by the arrival of suitor number one, Al St. John. Rube Miller, who is arguably the better-looking of the two suitors despite both a goofy and a geeky demeanor, breaks up the rendezvous by lowering a large spider on a string between the two lovers. From this point onwards, the action involves a battle between the two men, interrupted occasionally by the father, and culminates in a chase in which the antagonists are pursued by, of all things, a cannonball with smoke erupting from it.

While Alice Howell is not a major participant in the chase sequence, she does accept more than her share of violent confrontations, being hit by a rock, punched in the face, drenched with water (twice), smacked in the back, and sliding on her bottom down the steps from the house. Through it all, she overacts and overreacts—but not more so than her fellow actors, and certainly very much in the comedic style of the period.

Does Shot in the Excitement give evidence of Alice Howell’s performances to come? Arguably not. There is perhaps a hint of refined characterizations in the future, but it is only a mere suggestion, primarily through the physicality of the performance. If anything, she proves herself as much “one of the guys” as her male colleagues in the film.

Alice Howell had yet to formalize her grotesque make-up and attire—for example, the hair is already piled up on the head but in a strangely “skinny” fashion—yet it is very obvious that she paid attention to Chaplin’s advancement of his tramp character and his use of eccentric clothing. She realized that if she was to develop and grow as a comedy performer, she would need something equally original. At five foot three (or five foot six, according to her daughter), Alice Howell was too tall to be a conventional screen ingénue. In the modern sense, she needed a gimmick in order to succeed, and by piling her hair high upon her head in a frizzy, uncontrolled fashion, she was able to overemphasize, rather than reduce, her height. The “knob” of hair, as it was described, helped partially to hide her good looks.

The effect was enhanced by the addition of an eccentric costume, which unlike Chaplin’s tramp costume, did not remain the same in each production, but changed depending upon the characterization. She played different parts in different films, and so it was important for her exaggerated clothing to define those roles.

The other, strictly feminine, characteristic she adopts for use in her films is the bee-stung lips style of make-up. It was a style closely associated with, and generally adopted by, the more overly glamorous, vamp-like stars of the 1920s, such as Pola Negri or Gloria Swanson

Was she influenced by Chaplin? Yes and no. Without doubt, she understood what Chaplin was doing, what he had attained through the tramp attire. But she was a woman, and her approach had to be different. She couldn’t add a moustache or become a female version of a tramp, and so she worked with what she had—a fair amount of hair that could be styled to comic advantage, and an acrobatic, lean body upon which might be thrown any ill-fitting assortment of clothing. The only attribute that she did borrow from the Chaplin characterization was a sense of balletic rhythm, an ability to dance as much as merely walk. Her only female rival at Sennett, who also directed her, was Mabel Normand, and Normand never tried to hide her good looks. In 1915, Louise Fazenda joined Keystone, and, along with Polly Moran, who was already there, she might have provided formidable competition to Alice Howell, being equally adept at comic make-up and physical humor.

As film historian Rob King, who ignores Alice Howell in his study of the Keystone Company, has noted, “In effect, Fazenda and Moran filled a need created by Normand’s absence—namely for female performers willing and able to participate in knockabout action.”12

Alice Howell approached her unique characterization with a determination to deny just how attractive she was, while at the same time she displayed a physical style of comedy more associated with a male contortionist. The eyes and the face were expressive and female, but the body might just as well have belonged to a young man in good physical shape.

Yes, Alice Howell is an original character, unique to silent comedy. And, yes, I am not alone in acknowledging her as the female Chaplin. That being said, I would note that while Chaplin takes a more sophisticated and relaxed approach to his comedy, Alice Howell is positively frenetic in her comedy performances. It is almost as if not one second of time should be wasted in drama or pathos. It is comedy, comedy, comedy. Aim for the laughs, however low the humor.

Whereas Chaplin grew as a comedy star, perfecting his tramp costume, adding a level of sophistication in the form of pathos and more thoughtfully considered and constructed visual gags to his persona and his films, Alice Howell did not. The basic concept in terms of the make-up and the costume remained the same. The films might vary in storyline, and the costumes might not always be identical, but the structure was pretty much the same. If anything, this confirms that the star did not really care that much about her film career.

It would almost seem as if it was not worth the effort to work hard and grow as a comedienne. What one saw on screen was what she had to give, what she was willing to offer, and nothing more. Her métier, although she was perhaps unaware of it, was the comedy short. Unlike Chaplin, she was incapable of thinking to expand her role, her character, her plots to what would be needed for a feature-length production.

It is very obvious at Keystone that some of the players—notably, Chester Conklin and Hank Mann—have an almost innate ability to steal scenes. Alice Howell makes no attempt to shift the focus of the scene to her performance. Can this perhaps have been a weakness in her persona, or, perhaps more pertinently, is it simply that she had no genuine interest in what she was doing on screen—at least at this time?

With Mabel Normand very pointedly groomed by Mack Sennett as his company’s only star comedienne—whatever Normand wanted, she got—Alice Howell would need to look elsewhere to develop as a character and as a performer. The opportunity came with a suggestion from Keystone comedian Henry “Pathe” Lehrman that she join him as leading lady with the company he had recently created, Lehrman Knock-out Komedies, more formerly known as the L-Ko Motion Picture Company (L-Ko) or as the L-Ko Komedy Kompany. L-Ko was a successor to a short-lived earlier Lehrman enterprise, Sterling Comedies, featuring Sennett comedian Ford Sterling.

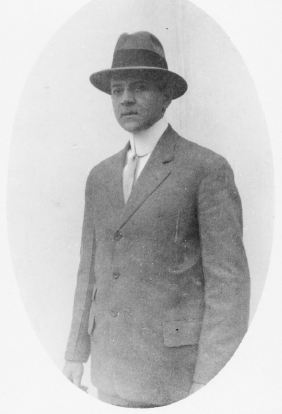

An early photograph of Henry “Pathe” Lehrman.

Henry “Pathe” Lehrman (1883–1946) is one of the more colorful and disreputable characters in screen history. He is generally described as vain, arrogant, rude, crude, and dishonest. “‘Pathe’ Lehrman was a terror,” exclaimed Yvonne Stevens. “Dick punched him in the nose for insulting a girl.”13

Lehrman claimed to have been born in Vienna and to have come to the United States in 1908 as a representative of the French Pathé Company. Lehrman’s background was every bit as romanticized and artificial as that of another supposed Viennese-born member of the film industry, Erich von Stroheim. In reality, Lehrman was a former streetcar conductor who worked at the American Biograph Company in New York for D. W. Griffith, who nicknamed him “Pathe” (without the acute accent over the “e”) in reference to Lehrman’s fake accent. In 1912, he had joined Mack Sennett’s company as a journeyman actor, cameraman, and director, and he contributed much to the structure and content of the Keystone films.

In 1916, Lehrman formed a relationship with Virginia Rappe, a minor actress, and perhaps part-time prostitute, who died in San Francisco in 1921 in the sex scandal involving Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle. The scandal garnered considerable publicity for Lehrman, whose career was in rapid decline. He told the New York Times (September 13, 1921) that he would gladly kill Arbuckle for his crime, commenting of Rappe that “she died game, like a real woman, her last words being to punish Arbuckle, that he outraged her and she begged the nurse not to tell this, as she did not want me to know.” Lehrman did at the least pay for Rappe’s burial in what is now the Hollywood Forever Cemetery. From 1928 until his death, Lehrman worked in the script department at Fox, later Twentieth Century-Fox.

Lehrman had utilized his time with Mack Sennett to study all aspects of comedy production, and, like his mentor, Lehrman boasted to the Los Angeles Daily Times that he had never used a script or scenario in L-Ko productions, “conceiving and executing as he proceeds.”14 Comic business and storylines were developed during extensive rehearsal periods. Neither at L-Ko, nor later, did Alice Howell write any of her own scripts; she did, however, contribute appropriate “funny business” to various scenes during the rehearsal stage.

A distribution deal was arranged with Universal, and production began at the old Universal Studios at 6100 Sunset Boulevard, at the corner of Gower Street, in Hollywood. Financial backing for Lehrman was provided by Abe and Julius Stern, who oversaw the company from their headquarters in the Mecca Building at 1600 Broadway in New York.

Whatever his faults, Lehrman did recognize talent, and it is to his credit that he saw in Alice Howell a comedienne worthy of more than supporting roles. “‘Pathe’ Lehrman thought she was wonderful,” said daughter Yvonne, and as far as Alice Howell was concerned, the feeling was mutual.