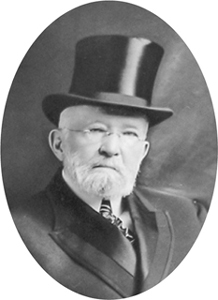

COLONEL EDMUND HAYNES TAYLOR JR.

DISTILLER, ENTREPRENEUR, AND LOBBYIST

1830–1923

![]()

Frankfort Cemetery, Franklin County, Kentucky

No whiskey historian can resist hypothesizing, with total disregard for the futility of the enterprise, on the inventor of bourbon. Never mind that bourbon always was—that there is no evidence that whiskey was ever not made from corn in the United States or ever not aged in charred barrels. Aged whiskey appears in advertisements around 1800, and ten-year-old whiskey was already being advertised in New Orleans in 1840.

Nonetheless, there have been many names thrown into the ring: Elijah Craig and Evan Williams are often nominated, and they are aided significantly by the marketing campaigns from the companies that make the whiskeys that now bear their names. Old George Thorpe gets a nod in at least two historical books, as do a number of candidates (Jacob Myers, Joseph and Samuel Davis, John Corliss, and the Tarascon brothers) courtesy of Mike Veach’s excellent bourbon history.

But if we are to credit these men as the founding fathers of bourbon, it was E. H. Taylor Jr. who saved bourbon from itself; consider him the spirit’s Abraham Lincoln.

Taylor was born well-off in Columbia, Kentucky. His father, a merchant trader who frequently traveled to New Orleans, died of typhus when Taylor was young, and for a time he lived with his great-uncle Zachary Taylor, who would serve as our twelfth president until his death in office. Uncle Zachary was a career general, and a lingering aphorism from his battle days—“General Taylor Never Surrenders”—followed in the family line.

Taylor spent his early years in banking and commodities trading, but with much of the South reeling from the war, Taylor entered into an industry that he imagined would bounce back quickly: the whiskey business. He set up an office in 1864, and in 1866 he traveled to Europe to explore the latest in distillery technologies. In 1869, he purchased the Swigert distillery and renamed it the O.F.C. distillery, which by most accounts stood for Old-Fashioned Copper (though George Stagg, the next owner, would later alter this to Old Fire Copper). The distillery used old-fashioned techniques (copious copper, low-distillation proof, limestone water) and new technologies like column stills to make whiskey. His brick warehouses were steam-heated in cycles, ensuring that the bourbon developed a rich and full flavor through a controlled aging process.

Taylor was as much a promoter as a distiller. Since his customers (retail stores or saloons) purchased whiskey by the barrel, he insisted they be cleaned up and fitted with brass rings. He offered letters of recommendation and prints of his distillery to wholesalers and retailers visiting the O.F.C. distillery, an early effort at marketing his products.

More important, Taylor became involved in protecting bourbon whiskey’s name from imitators. In those days (as now), many distillers would buy a commercially distilled whiskey in bulk, and bottle or package that whiskey under their own name. In most cases back then, this bulk whiskey was rectified whiskey, an inexpensive neutral spirit to which wood chips, glycerin, caramel coloring, and other adulterants were added to mimic the taste of bourbon. A generation before Taylor, “Old Whiskey” was shorthand for the best; Taylor helped make “Pure Whiskey” a whiskey advertiser’s most meaningful claim.

Taylor came to distilling from the finance and marketing aspect of the business, and thus was familiar with the mechanisms of power around business. He filed at least fourteen lawsuits to protect his trademark, according to Kentucky legal scholar Brian Haara. Taylor was also mayor of Frankfort, Kentucky, for most of the 1870s and 1880s. With the help of then U.S. Treasury Secretary John G. Carlisle (also from Kentucky), Taylor drafted the architecture for a federal guarantee of whiskey provenance, though courts were quick to insist that this was not the same as quality.

The Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 stipulates the highest class of American whiskey, more rigorous than any whiskey laws in any country before or since. To bear the “bottled in bond” designation, a whiskey must otherwise meet the criteria for straight whiskey, be distilled by a single distiller at one distillery in a single distilling season, be at least four years old, and be bottled at one hundred proof. The law has changed somewhat, mostly at the level of government supervision and the tax stamp requirements, but the thrust is the same: With a bonded bottle, you know where it comes from. It’s something that today’s consumers could use a little more often.

The bottling line at Old Taylor was designed as a part of the tour to reinforce the integrity of whiskey bottled at the distillery

At some point, Taylor began a private correspondence with Harvey Washington Wiley (see this page), and sent his son to testify on behalf of straight whiskey producers in hearings on the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, supporting truth-in-labeling requirements as part of a broader public concern over adulterated foods and the conditions of industrial production, given some recent public visibility through Upton Sinclair’s influential book The Jungle.

Taylor also invented one other thing of note: the distillery tour. Taylor felt that transparency was his great advantage in the marketplace. And so, in 1887, on Glenn’s Creek just south of Frankfort, he built a castle to whiskey. It was a more modern and elaborate version of the O.F.C. distillery he had purchased a few years before. And by inviting the public to visit, Taylor could connect directly to his eventual customers, not just the stores and saloons buying wholesale by the barrel. Trains would stop nearby so that passengers could enjoy the distillery’s grounds, with its main building of stone and crenelated battlements, a Roman fountain room where pools of limestone water reminded customers of the virtues of Kentucky’s geography, and a sunken rose garden planted perhaps in an effort to appeal to those that might not be as excited about a distillery tour (wives). Visitors left with a complimentary “tenth pint” bottle, which is likely the best tour souvenir ever offered, then or since.