VINTNER, HORSE RACER, AND DISTILLER

1827–1899

![]()

Evergreen Cemetery, Los Angeles, California

Despite its overwhelming contribution to the nation’s agricultural output, the West Coast has never had its fair share of distilleries. This may be because wine and beer were easily and excellently made, so there was not often reason to distill those products into other commodities. Also, the West was settled mostly after the advent of rail travel, and the early economic incentives for distillation, such as the reduction in weight of a commercial crop, no longer mattered as much.

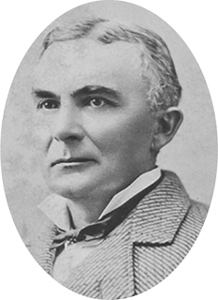

Still, there is a history, if mostly forgotten. Consider Leonard John Rose, who was born in Bavaria and immigrated to New Orleans as a boy. He moved his family westward, surviving an Indian attack near the Colorado River in Arizona and finally settled in Los Angeles in 1860. He grew lemon, orange, and olive trees, but he was best known for his vineyards, with grapes imported from Spain, Italy, and Peru. The farmhouse, known as Sunny Slope, a pre–Civil War structure, still stands in San Gabriel. The Lamanda Park neighborhood in Pasadena is a portmanteau of his first initial and his wife’s first name. He was also an avid breeder of fast horses and his breeding ranch Rosemead would one day become the city of the same name.

An 1886 article in the Los Angeles Herald paints Rose as a savior of the wine growers of Southern California. Grapes were looking to command such a low price that year that harvesting them wouldn’t even be worth it. Rose advocated for building a distillery, and a building on the other side of the Los Angeles River (accessible then via a covered bridge) was refurbished so as to produce a commodity from the grapes that could withstand fluctuations in price over the seasons.

The idea proved popular, and shares of the start-up distillery quickly went up in value. Zinfandel, muscat, and mission grapes poured into the distillery by the wagonload. As many as thirty-five four-horse teams were waiting with carts of grapes to be discharged. A fifteen-foot- diameter crusher, run with steam power, crushed the grapes into juice and pomace. The mixture was then conveyed to one of thirty-two seven-thousand-gallon vats, where it would ferment for eight days. A sluice conveyed the liquid to a ten-thousand-gallon concrete tank and then into a twenty-six-foot-tall wooden stripping still. The low-proof liquid that emerged was called singlings. Some of it was sent back to the pomace tank to feed into the strip still, but higher-poof liquor was sent to a copper-pot still for a secondary, polishing distillation. The emerging distillate—a clear, high-proof brandy—was diluted, barreled, and readied for sale. On a single day, there was enough pomace to produce seventeen thousand gallons of brandy.

Despite Rose’s success as a businessman, trade organizer, and politician, by 1899, his finances were in ruin. One day, after failing to secure a loan in San Francisco and later in Ventura, Rose told his wife that he would travel upstate on business. Instead, he secretly spent the evening at the family mansion, on Grand Avenue and Fourth Street in the Bunker Hill area of Los Angeles. He wrote his family a farewell note, stating that his financial difficulties were too much to bear. Also included was a postscript: “You will find my remains in the chicken yard.”

The note was received the following morning. No one at the house really wanted to run out and look at the backyard, so Rose’s son-in-law was called from his office downtown to inspect. He found, the Los Angeles Times wrote, “his father-in-law lying face downward in a little hollow at the rear of the lot. His head reclined on his hat, and in one hand was clasped a bunch of carnations.” To everyone’s surprise, Rose was not dead—not yet, at least—and doctors were immediately summoned to revive him. But Rose had taken a lethal dose of morphine, and it eventually kicked in.

The family sold the mansion on Bunker Hill, and by 1937 it was in such disrepair that the house was dismantled. The following year, its wood paneling was salvaged and used in the 20th Century Fox feature In Old Chicago.