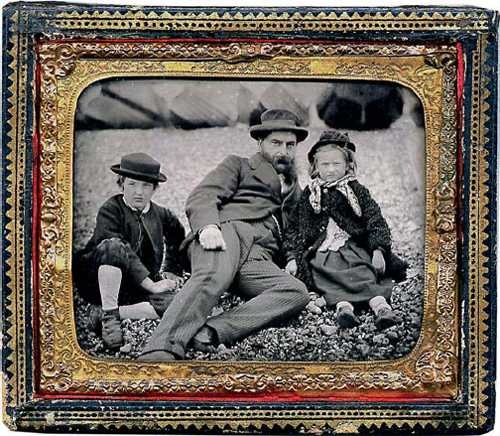

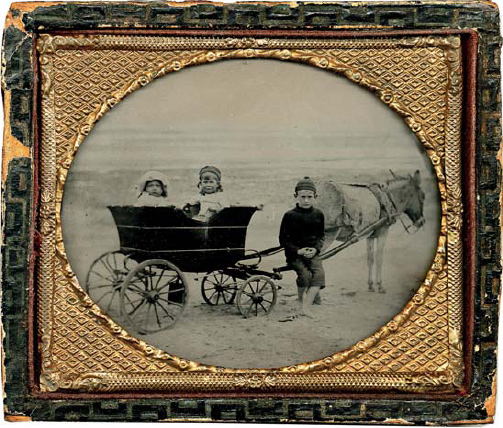

This 1/6th plate ambrotype – a direct positive image on glass – was taken by an unknown itinerant beach photographer in the 1860s or early 1870s. Travelling photographers used cameras with internal processing – which meant that the picture could be developed in a tray of chemicals at the bottom of the camera, the plate being manipulated by the photographer through light-tight arm holes. Such cameras meant that the photographer could travel and work anywhere without needing all the paraphernalia of a portable darkroom or darktent.

The whole idea of leisure time and leisure pastimes was, for the majority of people at least, a hard-won privilege unheard of before the nineteenth-century reforms of employment rights. Hitherto, such indulgences were the exclusive domain of the wealthy. Even photography itself was originally practised only by those with unlimited time and a deep purse – the first amateurs to travel with their cameras were land-owners, doctors, lawyers and the like.

It would be late in the Victorian era before the masses could afford to visit a photographer, and the early twentieth century (the box camera revolution) before they could afford to create their own mementoes of their leisure time, their holidays and their sporting enthusiasms.

Ironically, even the humble peasant had enjoyed more free time to pursue simple pleasures in medieval Britain than was available to the majority of workers at the beginning of the Victorian era. As will be seen elsewhere in this book, laws were passed in the fifteenth century to try and curtail the amount of time archers were spending playing golf. Four centuries later, the vast majority of people had neither the time nor the money for such indulgences!

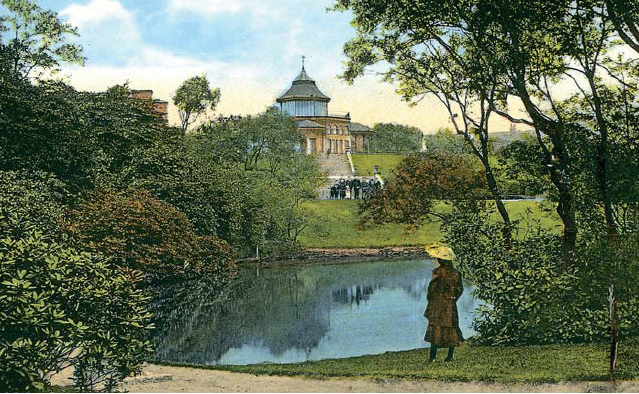

A young girl looks across the ‘serpentine lake’ in Wigan’s Mesnes (or Meynes) Park in 1905, towards a group of youths standing at the foot of the steps leading to the pavilion. Parks like this (Mesnes Park was created in 1877–8) were established in many towns throughout the country, funded partly by local authorities and partly by local mill, factory and colliery owners. In 1889 Wigan’s showpiece park was described as ‘one of the lungs of the town, a breathing spot for the thousands who, for most of their time, are cooped up in factories, collieries &c&… and in the spring and summer, Meynes Park presents a pretty sight.’

With no money to travel, and with limited free time anyway, the local park became a key component of the lives of working people. Local authorities, often prompted by generous endowments from local employers and landowners, developed beautiful municipal parks in most towns and cities, often with a pavilion, and invariably with a bandstand where local factory or church bands would perform on a Sunday afternoon.

All the parks had elaborate gardens, many had small serpentine lakes, and all were furnished with strategically positioned benches from which to enjoy the views.

Armies of gardeners and park attendants maintained and ruled these small patches of green in the midst of grim industrial urban areas. Their rules were published at the park gates, and those who ventured into their local parks understood and accepted that their demeanour and their behaviour had to conform. Walking or sitting in the park may have been a leisure activity, but it was still subject to accepted standards and disciplines.

One of the first ‘crazes’ of the photographic era was collecting and viewing 3D or stereoscopic images. From the late 1850s, every Victorian drawing room had a stereoscopic viewer – some of them simple hand-held devices, others elaborate pieces of furniture. New stereocards were published weekly, and were available through local print-sellers and photographic studios. The Stereoscopic Magazine in the early 1860s brought some remarkable 3D images to the notice of the public, albeit at a price that placed them beyond the budget of many. The London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company published hundreds of cards, many of them in large sets, covering subjects that ranged from educational – views of different parts of the world being very popular – to pure entertainment.

Genre cards included subjects ranging from historical re-enactments to humorous situations such as party games. Many of these images were later cropped down to the cartede-visite size print, which became the ubiquitous format of the 1860s and fitted the standard Victorian family album.

Lantern slide lectures were another popular entertainment. Village halls, church halls and assorted other locations were filled with people keen to hear stories from intrepid travellers who had journeyed to far-flung corners of the world.

For the really affluent, sets of slides in beautiful fitted wooden boxes could be purchased, complete with accompanying scripts, so that the lectures could even be delivered by those who had perhaps never been out of their own town!

There was a commonly held view amongst those Victorians who pioneered the great exhibitions that punctuated the second half of the century, that leisure time – in part at least – should be instructive. The Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in 1851 set a pattern of combining commerce with instruction, and people in their millions paid to pass through the turnstiles. Halls devoted to the art, culture and industry of different parts of the world were the popular attractions of the Great Exhibition, where visitors could learn something of the cultures of foreign lands – the sort of instructive entertainment we now get from television and from lavishly illustrated ‘coffee-table’ books. The Egyptian Court was a particular favourite, dominated by giant ‘mummy’ cases, a sphinx and palm trees.

‘Caught at Last’, one of a series of humorous stereoscopic genre cards from the late 1850s on the subject of party games. These cards were individually hand-tinted with coloured dyes by teams of women, each of whom might be responsible for only one of the colours. Five or six different colours have been used on this card, with the sepia colour of the albumen print providing the background.

When the Crystal Palace was dismantled and moved from its original site in Hyde Park to that part of Sydenham which bears its name to this day, the instructional and educational aspect was maintained, albeit with some less demanding entertainment added.

At around the same time, art schools started to open, offering the artisan and the craftsman the chance to take classes in a growing range of creative subjects.

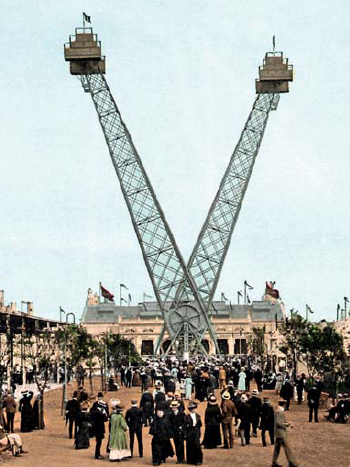

By the early years of the twentieth century, exhibition sites had to offer more – and the huge White City complex in London combined exhibition halls with a sports stadium and a number of purely recreational rides and experiences. The ‘Flip Flap’ was the most dramatic of the rides, while the scenic railway was probably the most popular.

Exhibitions fired an enthusiasm, at least amongst those who could afford it, for travel. For even the relatively well educated and well off, the chance to travel and to explore and experience other parts of Britain – let alone foreign countries – was a possibility only opened up in the mid nineteenth century, when statutory holidays were introduced at about the same time as the major railway expansion.

The ‘Flip-Flap’ was one of the most popular attractions at the Franco-British Exhibition, held in 1908 at the newly constructed White City complex in London. The site had been developed primarily for exhibitions, but a stadium was added to the plans when London took over the hosting of the 1908 Olympics from Rome.

This postcard, ‘Watching the Boats at Fleetwood’, was published in 1908. Above the ladies’ heads can be seen the twin funnels of the Londonderry steamer at the quayside.

The curiosity for experiencing travel to other parts of the country, and to other lands, is what brought Thomas Cook into the travel business – his first party of temperance travellers journeyed from Leicester to the Trossachs region of Scotland in the 1840s. It is interesting to note that Cook’s first package tour was for a working-class party and not the well off. These were people who had probably never seen the open countryside before!

By the mid 1850s, he was offering package trips to the Exposition Universelle in Paris – although the package-tour innovator had significantly failed to negotiate a cheap rate with the ferry owners on the channel.

The pictures in this book are drawn predominantly from the picture postcard – which in the Edwardian era was rather like the text message or email of today. It was a cheap, simple and reliable way of keeping in regular contact in the years before the telephone became commonplace in people’s homes. Thanks to a super-efficient postal service, postcards could be slipped into the postbox first thing in the morning with delivery locally almost guaranteed by lunchtime. In major towns and cities, there were half a dozen collections and deliveries a day, so it was possible to make arrangements by postcard to meet someone that same evening. As the popularity of this means of making contact increased, of course, it generated an enormous demand for the cards themselves.

The photographic postcard started to appear in the early years of the twentieth century, and for the first few years all cards had a little white strip along the bottom of the picture for a brief message – postal regulations permitted only the address to be on the reverse. Those restrictive rules were changed in 1902, and from then onwards the split-back card we still recognise today came into everyday use. That opened up the possibility of sending longer messages, further increasing the medium’s popularity, and by the middle of the century’s first decade, postcards were being bought, written and sold in their millions. Of course, as demand for picture postcards increased, so did demand for more varied photographs. It would appear that by 1905, just about every possible subject was considered saleable.

Postcard collecting was already an established hobby before the end of the nineteenth century, so as new card designs and themes were marketed, they were bought by collectors as well as by those wishing to send messages to friends. Subjects ranged from those we would still recognise today – famous buildings, landscapes and famous people – through to those cards that hold the greatest fascination for us today.

Some time around the turn of the twentieth century – 1903 or 1904 – innovative photographers and publishers introduced series of cards which celebrated the diversity of working life in Britain and, alongside the already established range of scenic views, these were quickly joined by cards depicting leisure pursuits as well. In many cases they were photographed and published locally – depicting local people at work and play. The photographs would be taken by a local photographer, providing a small but welcome additional source of income, and the fact that every aspect of the process was handled by local people who knew and understood the local lifestyle gives these postcards considerable importance as social history documents.

Children of all walks of life love dressing up! In 1854, Roger Fenton took this photograph of the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, dressed as ‘Winter’, with Princess Louise.

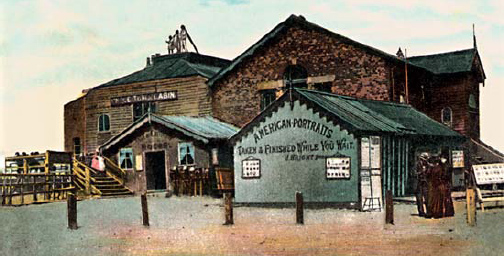

The photographer’s studio was a popular haunt for many holidaymakers. In the Victorian and Edwardian era, anything American was believed to be particularly exciting, so many seaside studios advertised themselves as producing ‘American portraits’ to give their work that special appeal!

It is hard for us to imagine today just how huge the impact of the photographic postcard was in this period, and perhaps even harder to imagine people today willingly posing for studies to be used in picture postcards. With very few exceptions, today’s postcard subjects are bland and have an impersonal timelessness, which of course ensures that they have a long shelf life. This reflects the relegation of the postcard solely to the role of tourist memento, the communication aspect having long since been taken over by other, faster media.

For the people who posed for these pictures, a small measure of local celebrity was assured for the lifetime of the postcard, and it must have been quite an attractive proposition to use cards that carried photographs of yourself or your friends. This was an inspired piece of local marketing, probably ensuring larger than usual sales. The photographers and publishers who created the cards, however, cannot have dreamed of the importance their enterprises would have a hundred years later in defining what life was like in the early years of the twentieth century.

Many of the cards were printed in colour, crude colouring being created by multiple chromolithographic printings, giving an added realism and appeal to the images. Few local printing works could handle such sophistication, so while black-and-white versions of popular local cards were printed locally, many of the finest coloured examples of the same pictures were printed in Saxony.

That gives some idea of the scale of production – it would not have been worthwhile going to the trouble of colourising the images and having them printed abroad if print runs were small – and it is a reflection on the fleeting and immediate nature of the postcard message that so few of them were saved for posterity.

After the First World War, the world was a very different place, the social order started to change, and the increasing availability of low-priced cameras changed the nature of the photograph from being something everyone bought, to something almost everyone made.

An itinerant photographer on Blackpool beach captured this study of three small children in their donkey cart in August 1882. Compared with children seen in many Victorian and Edwardian photographs, these children have the much more casual dress we would normally associate with holidays, perhaps reflecting their social status. Blackpool was, after all, proud to proclaim itself the holiday resort of choice for the working class – the mill, factory and mine workers of the industrial northwest, where wages were low, holidays were without pay, and for many a single day at the seaside was considered luxury indeed.

With the increasing popularity of the telephone, the picture postcard moved from being an essential means of communication to something approaching the ‘wish you were here’ role it retains to this day. The range of subjects reduced dramatically, and thus the postcard’s ability to reflect its age diminished. The window through which these early images let us look was not open for long!