2

Endowment Purposes

Institutions accumulate endowments for a number of purposes. A significant level of endowment support for university operations enhances institutional autonomy and provides an independent source of revenues, thereby reducing dependence on government grants, student charges, and alumni donations. Financial stability increases with the level of sustainable endowment distributions, facilitating long-term planning and increasing institutional strength. Finally, since colleges and universities tend to post strikingly similar tuition levels, better-endowed institutions enjoy an incremental income stream, providing the means to create a superior teaching and research environment.

Institutions without permanent financial resources support day-today operations with funds from sources that frequently demand a voice in organizational governance. Government grants expose colleges and universities to a host of regulations concerning matters far afield from the direct purpose of the activity receiving financial support. Gifts from alumni and friends often contain explicit or implicit requirements, some of which may not be completely congruent with institutional aspirations. In an organization’s early years, when any source of income might represent the difference between survival and failure, institutions prove particularly vulnerable to the strings attached to external income flows.

Universities frequently make long-term commitments as part of the regular course of operations. For example, awarding tenure to a faculty member represents a financial obligation that might span decades. Funding such an enduring obligation with temporary sources of funds exposes the institution (and the individual) to the risk of disruption in revenue flows. The permanent nature of endowment funds matches nicely the long-term character of tenure commitments.

Some institutional constituencies view endowments with a decidedly short-term horizon. Students generally prefer greater levels of support today, expecting that higher expenditures translate into better, less expensive education. Faculty recognize that current resources provide the wherewithal to pursue a more comprehensive set of scholarly activities, while administrators see enhanced financial flows as the means to relax the binding constraint of budgetary discipline. Some donors suggest increasing endowment payout as a means to reduce the pressures associated with raising current use funds. Trustees ultimately face the difficult-to-resolve tension between desire to support current programs and obligation to preserve assets for future generations.

Colleges and universities stand among the most long-lived institutions in society. By charting an independent course in fulfilling a mission of teaching and scholarship, the academy adds immeasurably to the quality of life. Endowment funds contribute to the educational enterprise by providing institutions with greater independence, increased financial stability, and the means to create a margin of excellence.

MAINTAIN INDEPENDENCE

Endowment accumulation facilitates institutional autonomy, since reliance on impermanent income sources to support operations exposes institutions to the conditions attached by providers of funds. For example, when the government awards grants to support specific research projects, university-wide activities frequently face requirements and regulations even though the affected operations may be far removed from the grant beneficiary. Similarly, colleges relying on donor gifts for current use often find that benefactors demand a significant voice in the institution’s activities. Even educational institutions that rely heavily on tuition income may be constrained by that dependency, perhaps by responding to current trends and fashions to attract sufficient numbers of students to maintain operations. Greater institutional needs for current income correspond to greater degrees of external influence.

Educational institutions certainly must respond to government policy and take into account donor wishes and student desires. However, at times such influences detract from the ability of trustees to pursue well-considered institutional goals. Endowment accumulation allows educational institutions to be accountable to their constituencies without being held hostage by them.

Donors to endowment often attach meaningful restrictions to gifts, stipulating that funds provide permanent support for designated purposes. Occasionally, such requirements come into conflict with institutional goals, as might be the case when an endowment supports a field of study long since abandoned by scholars. More frequently, endowment gifts provide restricted support to fund activities central to organizational aspirations, such as teaching and financial aid. Even though donors exercise considerable influence in negotiating the initial terms of an endowment gift, after establishing the fund, donor influence wanes.

Attracting short-term sources of income requires institutions to respond to a combination of explicit and implicit pressures. Institutions that benefit from a stable stream of endowment income stand a greater chance of maintaining independence from external pressures. Support of the operating budget by endowment fosters academic freedom and allows independent governance.

Yale and Connecticut

The survival of the fledgling Yale in the early eighteenth century depended on generous legislative and financial support from the Colony of Connecticut. In October 1701 the General Assembly of the Colony of Connecticut approved a proposal put forth by five Connecticut ministers to charter a college: “Wherein Youth may be instructed in the Arts and Sciences who through the blessing of Almighty God may be fitted for Publick employment both in Church and Civil State.” Support for Yale included grants of land, special grants for construction or repair of college buildings, authorization for briefs or lotteries, duties on rum, and the exemption of ministers, ministers’ tutors, and students from taxes. Brooks Mather Kelley, in his Yale—A History, estimates that “throughout the eighteenth century, Connecticut’s contribution amounted to more than one half the total gifts to the college.”1

The colony’s support came with a price. For instance, in 1755, the general assembly voted to refuse the annual grant to Yale, ostensibly because of wartime expenditures, but in fact to retaliate for a controversial position taken by Yale President Clapp concerning the religious character of the college. In 1792, in exchange for renewed financial support, the governor, lieutenant governor, and six legislators became fellows of the Yale Corporation. The presence of the state-appointed representatives on the Yale governing board caused discord and conflict, with disagreements ranging from the proper religious faith of the faculty to the general assembly’s rights in reforming abuses in the running of the college.

State-appointed representatives served on the Yale Corporation until the termination of state support for Yale in 1871, which resulted in the withdrawal of the state senators from the Yale Corporation.2 With the replacement of the six legislators by fellows elected by Yale’s alumni body, control became more firmly centered in the college. Yale’s experience mirrored national trends. With the end of the Civil War and the rise of Darwinism and laissez-faire philosophies, the previous view of the major role of the state in the support of private education had shifted. As historian Frederick Rudolph noted, “a partnership in public service, which had once been essential to the colleges and inherent in the responsibilities of government…[became] insidious or…forgotten altogether.” Fortunately for Yale, this withdrawal of public support was replaced by organized alumni support.3

The appointment of elected officials to the university’s governing board in exchange for financial support illustrates in the starkest fashion the loss of control associated with reliance on external sources of funds. While the nearly eighty years of direct state influence on Yale’s governance represents an extreme case, more subtle issues of outside influence continue to test the wisdom of today’s trustees. Balancing the legitimate interest of providers of funds in having a voice with the fundamental need of private institutions to maintain ultimate control poses a difficult challenge to fiduciaries responsible for managing educational organizations.

Federal Support for Academic Research

The benefits and dangers of reliance on government support have shaped private educational institutions throughout their history. Many scholars credit the influx in the 1960s of federal dollars for research in higher education with the rise to preeminence of the American research university. However, the costs of this support to the administrative flexibility of the universities became painfully evident in the 1970s.

In their extensive study of the American research university, Hugh Graham and Nancy Diamond note that federal support for research resulted in “increased congressional involvement, an emphasis on targeted research, and a general trend toward government regulation of the private sector.”4 During the late 1960s and early 1970s federal regulation of universities slowly but steadily embraced issues such as hiring, promotion, and firing of university personnel (including faculty); research; admissions; toxic waste disposal; human and animal subjects of research; access for the handicapped; wage and salary administration; pensions and benefits; plant construction and management; record keeping; athletics; fund-raising; and in some cases, curricula.5

With this new web of federal regulation came increased costs and bureaucracy for the universities. In a widely quoted claim, Harvard President Derek Bok noted that compliance with federal regulations at Harvard consumed over sixty thousand hours of faculty time and cost almost $8.3 million in the mid 1970s. A 1980 study found that meeting regulatory costs absorbed as much as 7 to 8 percent of total institutional budgets.6

The reduction in administrative autonomy poses a significant threat to institutional governance. In his Report of the President for 1974–1975, Yale President Kingman Brewster stated: “…the experience of recent years gives fair warning that reliance upon government support for any university activity may subject the entire university to conditions and requirements which can undermine the capacity of faculty and trustees to chart the institution’s destiny.”

When well-endowed institutions accept external financial support, compliance with the accompanying requirements no doubt influences institutional policies. That said, such compliance generally poses no fundamental threat to the integrity of the institution. The greater the independent flow of financial resources from endowment assets, the greater the ability of an institution either to avoid external funds with onerous requirements or to negotiate changes mitigating undesirable regulations. In cases where organizations lack substantial independent means, external funds providers wield the potential to reshape the institution, threatening to alter the fundamental character of the college or university.

University of Bridgeport

In the early 1990s, severe financial distress caused the University of Bridgeport to lose its independence after a desperate fight to survive. From a peak of more than 9,000 students in the 1970s to fewer than 4,000 in 1991, declining enrollment created budgetary trauma, forcing the school to consider radical measures. In spite of the institution’s dire straits, in October 1991, the University of Bridgeport rejected an offer of $50 million from the Professors World Peace Academy, an arm of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church. Preferring to pursue independent policies, the institution’s trustees elected to take the drastic step of eliminating nearly one-third of its ninety degree programs, while petitioning a judge to dip into restricted endowment funds to meet payroll costs.

After running out of options in April 1992, the trustees of the university reversed course, ceding control to the Professors World Peace Academy in exchange for an infusion of more than $50 million over five years. As board members associated with the Unification Church took control, the sixty-five-year-old institution received a new mission:—to serve as “the foundation of a worldwide network of universities striving for international harmony and understanding.”7

Three years later, the Reverend Sun Myung Moon received an honorary degree from the University of Bridgeport, which recognized him as a “religious leader and a man of true spiritual power.”8 During Reverend Moon’s appearance on campus, he took credit for the fall of communism and promised to resolve conflicts in the Middle East and Korea. Claiming that “the entire world did everything it could to put an end to me,” the Reverend Moon said that “today I am firmly standing on top of the world.”9 According to the New York Times, the speech provided further evidence to critics that the “once sturdy university” sold its independence for an infusion of capital from “a religious cult with a messianic and proselytizing mission.”

The University of Bridgeport’s demise resulted from a number of factors, yet a more substantial endowment might have allowed the institution to maintain its independence. The lack of a stable financial foundation exposed the university to wrenching change, causing varying degrees of distress among important institutional constituencies.

External support for colleges and universities frequently comes with collateral requirements designed to influence institutional behavior. In extreme cases, outside agents seek to change the fundamental character of an organization. The greater the extent to which endowment funds provide support for operations, the greater the ability of an institution to pursue its own course.

PROVIDE STABILITY

Endowments contribute to operational stability by providing reliable flows of resources to operating budgets. Nonpermanent funding sources fluctuate, and may diminish or disappear, as government policies change, donor generosity diminishes, or student interest wanes. By reducing variability in university revenues, endowments enhance operational viability and promote long-term planning.

Yale and Josiah Willard Gibbs

Yale’s history is riddled with instances of budgetary problems due to fluctuating current income. On numerous occasions the university operated at a deficit, forcing faculty to forego full salaries. In an extreme example, the “greatest scholar Yale has ever produced or harbored,” Josiah Willard Gibbs, renowned for his seminal research in physics and engineering, received an appointment as professor of mathematical physics without salary in 1871, indicating “not any lack of esteem for Gibbs, but rather the poverty of Yale.” In 1880, officials at Johns Hopkins University attempted to woo Gibbs from Yale with an offer of a $3,000 salary.

The well-known geologist and mineralogist, Yale Professor James Dwight Dana, convinced Yale President Noah Porter to provide Gibbs with a salary of $2,000 and a promise to increase the salary as soon as funds were available. In a letter to Gibbs, Dana implored the brilliant professor to stay loyal to Yale: “…I do not wonder that Johns Hopkins wants your name and services, or that you feel inclined to consider favorable their proposition, for nothing has been done toward endowing your professorship, and there are not here the means or signs of progress which tend to incite courage in professors and multiply earnest students. But I hope nevertheless that you will stand by us, and that something will speedily be done by way of endowment to show you that your services are really valued…Johns Hopkins can get on vastly better without you than we can. We can not.”10

Gibbs eventually received Yale’s prestigious Berkeley fellowship for postgraduate scholarship, endowed in 1731 by George Berkeley with the gift of a ninety-six-acre farm in Newport, Rhode Island. Funded by income from the farm, the fellowship supported some of Yale’s most illustrious graduates including Eleazer Wheelock, the first president of Dartmouth College, and Eugene Schuyler, the first American to hold the Ph.D.

Today, endowed chairs serve largely to confer honor on distinguished faculty members; in Gibbs’s era support from the endowment conferred both prestige and financial security. That said, even today, the credibility of an institution’s promise to provide ongoing financial support creates an important competitive edge in recruiting and retaining faculty.

Stanford University

Endowment distributions occasionally provide more than year-to-year stability in funding operations. In times of severe economic stress, well-endowed institutions employ extraordinary distributions to weather the storm, while those with meager permanent resources face the consequences of substantial financial trauma more directly.

In 1991, Stanford lost significant amounts of financial support from the federal government in a controversy over cost recoveries that the university claimed in connection with federally sponsored research activity. Stanford allegedly overbilled the government, seeking reimbursement for headline-grabbing charges associated with the seventy-two-foot yacht Victoria, a nineteenth century Italian fruit-wood commode, and a Lake Tahoe retreat for university trustees.11 Primarily as a result of the “continued impact of the disputes with the federal government,” the university posted a 1992 operating deficit in excess of $32.5 million, representing nearly 3 percent of revenues.

Facing projected deficits aggregating $125 million over three years, Stanford sought to “finance the expected losses while expense reduction programs were implemented.” A critical component of the “financing” plan involved increasing the endowment payout rate from 4.75 percent to 6.75 percent for 1993 and 1994, releasing a projected incremental $58 million to support operations during Stanford’s period of adjustment.

The combination of increased endowment spending, reduced expenditures, and incremental borrowing placed the university on firm financial footing. In 1995, basking in the glow of a substantial operating surplus, Stanford lowered the payout rate to 5.25 percent, nearly returning to the “customary rate of 4.75 percent.”12 The extraordinary increase in the endowment spending rate provided a cushion for Stanford’s operations, allowing the university to deal with a sudden, significant loss of funds with minimal disruption.

Yet the use of permanent funds to finance temporary operating shortfalls imposed substantial costs on Stanford. In the five years following the university’s extraordinary payout rate increase, strong investment returns led to more than a doubling in asset values. Certainly, with twenty-twenty hindsight, Stanford would have benefited by using much lower-cost external borrowing to fund the budget deficits, leaving the payout rate at its “customary” level of 4.75 percent. Considering the longer-term impact of withdrawal of permanent funds reinforces concerns regarding the ultimate cost of unusually high rates of spending from endowment.

Reliable distributions from endowment contribute to the stability of educational institutions. Under normal operating circumstances, greater levels of endowment serve to improve the quality of an organization’s revenue stream, allowing heavier reliance on internally generated income. When faced with extraordinary financial stress, endowment assets provide a cushion, either by paying out unusually large distributions or by serving as support for external borrowing, giving the institution the capacity to address disruptive fiscal issues. A substantial endowment creates a superior everyday budgetary environment and enhances the ability to deal with unusual financial trauma.

CREATE A MARGIN OF EXCELLENCE

Endowments produce resources that allow an institution to establish a superior educational environment. On the margin, endowment income attracts better scholars, provides superior facilities, and funds pioneering research. While financial resources fail to translate directly into educational excellence, incremental funds provide the means for the faculty, administration, and trustees to develop an unusually robust educational institution.

Endowments and Institutional Quality

Endowment size correlates strongly with institutional quality. A survey of major private research universities shows that larger, better-endowed organizations score more highly in the U.S. News and World Report rankings of educational institutions.13 While the U.S. News and World Report rankings garner a fair share of controversy, much of the debate centers around the rank order of institutions. Placing the major research universities into quartiles reduces the focus on numerical order and produces a set of categories that group like with like. The quartile groupings show a strong correlation between excellence and endowment size.

Public universities fall outside of the study because budgetary issues for state-supported institutions differ significantly from those of private universities. For example, government appropriations play a much greater role for public institutions than for private. If public authorities wish to support institutions at a particular level, changes in levels of endowment income might be offset by altering levels of state support for the universities. Strong endowment distributions may correspond to weak state subventions, while weak endowment support may elicit higher state contributions. Public institutions face investment and spending problems that differ fundamentally from those of private universities.

Major private research universities have strikingly similar tuition streams. In 2004, among the top twenty research universities in the survey, undergraduate tuition ranged from $19,670 to $32,265, a reasonably tight band. Eliminating the high and low outliers produces a range of $24,117 to $29,910. Among the top five institutions, tuition charges fell in an even narrower band from $28,400 to $29,910. Price discrimination, at least with respect to posted tuition levels, appears to be quite weak among leading universities.

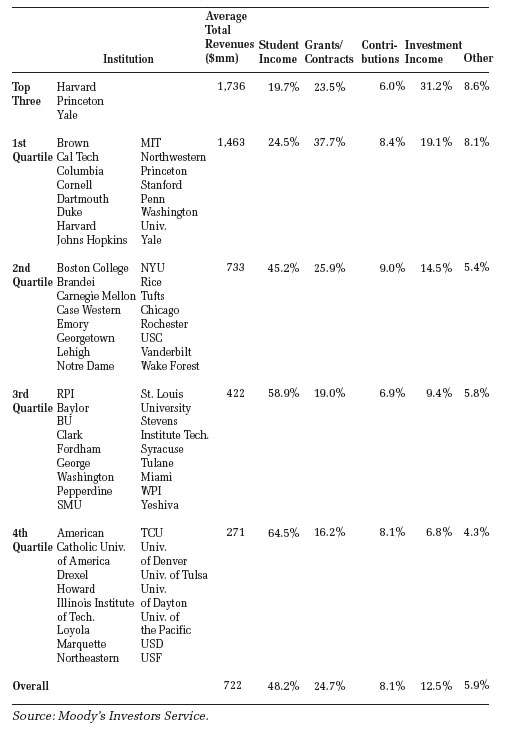

Large private universities operate substantial enterprises, with 2004 revenues ranging from $74 million to nearly $2.8 billion, averaging $722 million. To put the revenue numbers in a corporate context, eleven of sixty-one institutions run budgets sufficiently large to rank among the Fortune 1000 companies.14

Student income provides the largest single source of income to research universities, accounting for more than 48 percent of revenues. Grants and contracts supply nearly 25 percent of cash flow, investment income about 13 percent, and contributions 8 percent. The catch-all remainder amounts to less than 6 percent of revenues.

Ranking institutions by quality poses a host of challenges, because such rankings involve reducing the characteristics of a complex, multifaceted institution to a single number. Nonetheless, a cottage industry, led by U.S. News and World Report, produces widely followed annual ratings of colleges and universities.

In part, because of the impossibility of making precise distinctions where none exist, the ratings engender controversy. In the U.S. News and World Report evaluation, the magazine assesses academic reputation, student retention, faculty resources, admissions selectivity, financial wherewithal, graduation rates, and alumni giving rates.15 Combining measures such as SAT scores, class size, and graduation rates, the publication fashions a ranking scheme of colleges and universities. While the precise rank order causes much debate, the general groupings of institutions make intuitive sense.

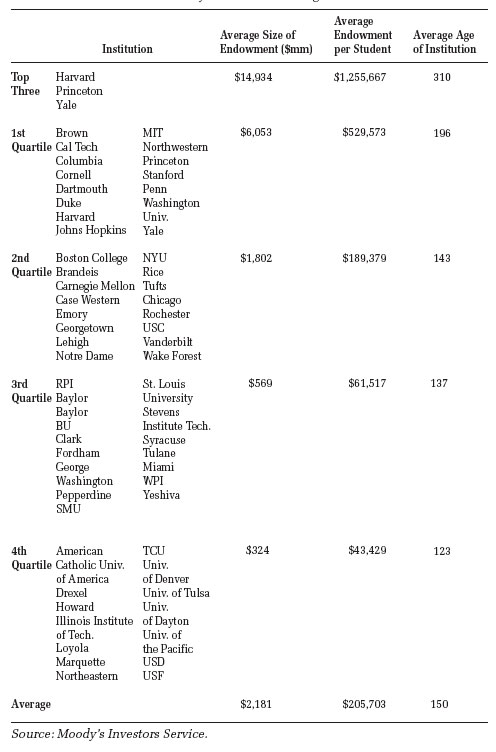

Dividing the large private universities into quartiles according to their academic ranking allows examination of the relationship between investment income and institutional quality. Table 2.1 lists (alphabetically) the institutions falling into each particular group.

Quality ranking and endowment size exhibit a strong correlation, with top quartile institutions benefiting from endowments averaging just in excess of $6.0 billion, in contrast to the bottom quartile average of $324 million. Moving from one quartile to the next, a clear step pattern emerges, indicating a direct relationship between endowment assets and institutional achievement.

The level of endowment per student tells the same story. Top quartile universities enjoy nearly $530,000 in endowment assets for each full-time equivalent (FTE) student. After dramatic declines to approximately $190,000 for the second quartile and just over $61,000 for the third quartile, bottom quartile institutions average only $43,000 per student. Endowment size correlates clearly and strongly with institutional quality.

The degree to which investment income supports research institution budgets varies dramatically. As seen in Table 2.2, top quartile university investment assets produce 19.1 percent of revenues. In contrast, bottom quartile institutions receive roughly one-third the relative support, with investments contributing 6.8 percent of income.

Since higher quality institutions tend to be larger, greater relative levels of investment income translate into dramatically greater numbers of dollars. Top quartile institutions operate with an average draw of $274 million, while lower quartile universities receive only $17 million.

Student charges provide the complement to investment income. As institutional quality increases, budgetary dependence on student charges decreases. Top quartile institutions rely on student income for 24.5 percent of revenues, while bottom quartile universities obtain 64.5 percent of revenues from such charges, a spread of 40 percent. Lower quality institutions rely heavily on tuition. Yet viewed on a per capita basis, student charges show a remarkably consistent pattern across the quartiles, with figures ranging from $26,800 for the top quartile to $19,400 for the bottom quartile. Better-endowed universities use their financial strength to create a richer educational environment.

Grants and contracts display a strong relationship with institutional quality, providing nearly 38 percent of revenues for top quartile institutions and declining monotonically to just over 16 percent of revenues for bottom quartile universities. As in the case of investment income, the combination of the top institutions’ larger budgets and larger shares translates into substantially more grant and contract income for research activity at large, high quality universities.

Table 2.1 Endowment Size Correlates Strongly with Institutional Quality

Data as of Fiscal Years Ending 2004 Source: Moody’s Investors Service.

Table 2.2 Investment Income Provides More Support at Top Universities

Data as of Fiscal Years Ending 2004 Source: Moody’s Investors Service.

Annual giving numbers fall into a reasonably narrow range from 6.9 percent to 9.0 percent of revenues and exhibit no particular pattern. Even though top quartile universities receive a smaller percentage of revenues from current gifts, the dollars given to top quartile institutions exceed the dollars for all other institutions combined.

While endowment size clearly correlates with institutional quality, the direction of causality remains unclear. Do higher quality institutions attract higher levels of endowment support, creating a self-rein-forcing virtuous cycle? Or do larger endowments provide the resources required to build superior institutions, facilitating the creation of a margin of excellence? Regardless of the direction of causation, greater financial resources correlate with superior educational environments.

CONCLUSION

Endowments serve a number of important purposes for educational institutions—allowing greater independence, providing enhanced stability, and facilitating educational excellence. Institutions of higher education best serve society as independent forums for free and open inquiry, promoting unfettered pursuit of ideas regardless of convention or controversy. The conditions attached to sources of outside financial support contain the potential to create institutional sensitivities, limiting healthy debate and impairing open inquiry.

For established institutions, endowments enhance operating independence and budgetary stability. Sizable reserves of permanent funds allow trustees to resist government interference and unreasonable donor requirements. Large endowments enable administrators to smooth the impact of financial shocks, buffering operations against disruptive external forces.

For less established institutions, endowments sometimes determine the difference between survival and failure. In the decade ending June 2007, more than one hundred degree granting institutions closed, representing approximately 3 percent of the total number of such institutions in the United States.16 Well-endowed institutions enjoy a level of fiscal support that cushions financial and operating blows. Even modest endowments make a significant difference.

Endowments provide the means to produce a margin of excellence. Better-endowed institutions enjoy an incremental source of funds available for deployment to create a superior educational environment. By contributing to the excellence of superior colleges and universities, endowments play an important role in the world of higher education.

Understanding the purposes that drive endowment accumulation represents an important first step in structuring an investment portfolio. By defining the reasons endowments exist, fiduciaries lay the groundwork for articulation of specific investment goals, shaping in a fundamental manner the investment policy and process.