CHAPTER 7

An Angel on Each Shoulder

FIFTEEN MILES TO THE EAST of Utah, out at sea, Lieutenant John Spalding heard throttles open and then what felt like a race to shore began. “I know that the Light Brigade and Pickett’s Charge flashed through my mind at that beautiful moment,” recalled one of Spalding’s 1st Division comrades. “It was pure excitement!”1 The thirty-one men under Spalding’s command, each with a red number 1 stitched onto a brown patch on his left sleeve, hunched down as the craft crashed violently into surf and plumes of spray flew into the air and landed on their webbed helmets.

Not one man spoke. There was no more singing, no more “whistling in the dark,” no more jokes about the saucy English broads they’d left behind in England.2 They were badly weighed down with equipment: flamethrowers, Bangalore torpedoes, heavy radios, even ladders to throw across anti-tank ditches. What would happen, Spalding worried, if they landed in deep water? Having to shout to be heard above the engines, Spalding ordered them not to jump out until he had gone first and tested the water’s depth.3 They were around two hundred yards from the beach when one of the British naval crew on his craft pulled the trigger on a machine gun mounted on the stern, and opened fire.

In a machine gun nest at WN62, the most heavily defended strongpoint on Omaha, which overlooked Easy Red sector, a twenty-one-year-old corporal watched boats in the first wave plow through the heavy seas, oddly dispersed, having been pushed off course by the strong tides and wind.

The all-important order had already been given: “Hold your fire until the enemy is coming up to the water line.”4

There were several earthshaking explosions caused by Allied naval fire, then the corporal’s immediate superior appeared, a shell splinter having hit him in the throat. “Just a little splinter, nothing serious. Everything all right here?”

“So far,” replied the corporal, who then saw that the ramps of some craft were dropping. It was 6:30 A.M.: H-Hour on Omaha Beach.

The first wave had arrived.

“They’re getting into the water now,” someone called out.

The corporal sent a frantic message to WN62’s observation post: “Landing troops disembarking.”

“They must be crazy,” said a German sergeant. “Are they going to swim ashore, right in front of our muzzles?”

A lieutenant finally gave the order for the men at WN62 to open fire, and within seconds a torrent of bullets were slicing toward the first wave as it landed on Easy Red, 57-millimeter rounds pinging against metal ramps, ripping through plywood hulls, zipping into the surf.

Aboard Lieutenant Spalding’s landing craft, a man shouted for the ramp to be dropped, but it didn’t budge. Spalding and a sergeant kicked the ramp until it slammed down.5 Spalding was first off, dropping into heavy seas just to the left of the ramp. The noise of battle was constant as he headed for the beach. He could hear small arms fire and the distinct snarl of German MG42 machine guns, which had a far higher rate of fire than any Allied weapon. One well-aimed burst could kill his entire platoon in seconds.

The water was up to his waist and he waded toward the shore, holding his carbine above the waves, his soaked woolen trousers like lead weights, but then he came across a runnel so deep he couldn’t cross it without swimming. He and men nearby inflated their life vests. “There was a strong undercurrent carrying us to the left,” he remembered. “I swallowed so much salt water trying to get ashore. I came so near to drowning.” Thanks to his life vest, he was able to keep his head above water.6

As he neared the beach, Spalding spotted his second in command, Sergeant Streczyk, and a medic. Together they were trying to carry an eighteen-foot ladder designed to cross anti-tank ditches, but they were struggling to keep ahold of it in the heavy seas.

Spalding grabbed for the ladder.

“Lieutenant, we don’t need any help,” shouted Streczyk.7

Spalding had a higher rank. He may have been in combat for only a few minutes, but he was already a changed man, no longer a callow neophyte, terrified of how he might fail. His job was to lead his men off the beach, and if he gave a goddamned order, as bullets zipped and whistled past his head, by Christ he expected it to be carried out. They were to abandon the ladder, he shouted, and they did so. Then he was able to stand once more, the water now up to his chin, surf breaking over his shoulders. “I had swallowed about half of the ocean,” Spalding remembered, “and felt like I was going to choke.”

A private carrying a seventy-two-pound flamethrower cried out for help, and Sergeant Streczyk told him to dump it. The private did as he was ordered, and others followed suit, abandoning equipment. Before long, Spalding’s men had little left to fight with. “In addition to the flamethrowers and many personal weapons,” recalled Spalding, “we lost our mortar, most of the mortar ammunition, one of our bazookas, much of the bazooka ammunition.”

Spalding finally waded out of the water. He looked ahead, across three hundred yards of sand, scarred by ugly black beach defenses—mine-tipped logs driven into the sand and six-foot-high steel hedgehogs. “I was considerably shaken up. Completely soaked, my equipment, heavy when dry, seemed to weigh a ton.” He saw the ruins of a house at the base of bluffs. It resembled one he had been shown in a briefing.

“Damn,” said Spalding. “The navy has hit it right on the nose.”

Other men moved forward and opened fire when they reached the sands. Close to Spalding, a rifleman was hit in the foot. He fell and then struggled to remove his leggings, unable to reach the lacing. Spalding helped him get the legging off and then looked up and saw some of his men crossing the hard, gray sand, bullets stitching toward them. They were soaked and too heavily burdened to sprint toward the nearest cover at the base of the bluffs. They should have gone in with as little weight as possible, like Rangers, and now looked as if they were “walking in the face of a real strong wind,” Spalding remembered.8 “It was just a slow, methodical march with absolutely no cover up to the enemy’s commanding positions,” recalled a fellow officer from E Company. “Men fell, left and right . . . Others staggered on to the obstacle-covered, yet completely exposed beach.”9

It occurred to Spalding that he should contact his company commander. He crouched down with his foot-long SCR-536 radio and pulled out the antenna. “Copper One to Copper Six.”

There was no answer.

“Copper One to Copper Six. This is One. Come in Copper Six.”

No reply.

Spalding looked at the radio. What was wrong with it?

Its black mouthpiece had been blown off. It was useless, but Spalding’s training had kicked in and he instinctively, by rote, took the antenna down, careful not to break it, and put the radio back over his shoulder, so scared he could not think straight.10 Then he moved across some shingle, smooth gray stones slowing him, to the blasted ruins of the building that he and others would later describe in remarkably detailed after-action reports as “Roman ruins.” He looked around and realized the building was different from the one in his planned landing zone, some five hundred yards to the west. As with all but one of the eight infantry companies to land in the first wave on Omaha, Spalding’s unit had come ashore far from where intended.

The German fire was unrelenting, a constant stream of bullets slashing through the air above Spalding’s head, pockmarking a wall a few feet from him and then killing a sergeant nearby. To his left he could see the source of the fire, WN62, and he watched as an MG42 scythed down men from F Company as they staggered across the beach. Powerless to help, he looked to his right, to the west, where E Company was supposed to have landed, and couldn’t see a single GI. What had happened to the rest of E Company? Had they all been slaughtered? Down at the waterline, some landing craft had been hit and were burning, clouds of tar-black smoke spiraling into the sky. It was a truly apocalyptic scene, never to be erased from his memory. Spalding decided it was best if he didn’t look back again.

A lump of shrapnel hit a private close by in the shoulder with a hard punch, the metal lodging in his upper body, knocking him down.11 A sergeant had managed to keep ahold of a Bangalore torpedo and had placed it below curls of barbed wire, and now he exploded its charge, blowing open a gap with a sharp blast. Beyond lay thick brush and then a steep incline to the top of the bluffs. Sergeant Streczyk and a private, scouting ahead, discovered a minefield but also a path of sorts created by water that had washed through the brush.12 The private returned and told Spalding and others to follow him. As they did so, a machine gunner directly above, near the top of the bluffs, pressed his finger on a trigger. Bullets kicked up the ground all around them, but they advanced regardless and Spalding kept his head up, scanning the bluffs.

“Lieutenant,” a sergeant said. “Watch out for the damn mines.”

The area was “infested’ with small wooden box mines, but Spalding couldn’t see any. Stepping carefully, he continued up the bluffs, through thick brush and seagrass and the gnarled stumps of windblown bushes.

“Watch out for the damn mines.”

Up they climbed, and then they were through the mined area. None of his men were hurt. It seemed like a miracle. None had stepped on a mine. “The Lord was with us,” recalled Spalding, “and we had an angel on each shoulder on that trip.” The Lord had indeed been with them. Just a couple of hours later, several men from H Company would be lost as they crossed the very same ground.

The machine gun was still spitting bullets from above, its barrel growing hot. There was a deep boom as a sergeant fired his bazooka at the machine gun’s position. But the sergeant missed and was shot in the left arm, and then a private was hit. The sergeant came up to Spalding and proudly displayed his wound—a bullet had gone through his arm just above the wrist. He’d now been in three invasions: North Africa, Sicily, and Normandy. Finally, he’d gotten the “million dollar wound” so many GIs hoped for, serious enough to be sent home but not life-threatening.

“Gee, Lieutenant, ain’t it a beauty?” said the sergeant.

Men nearby looked jealous.

Spalding kept moving, following Sergeant Streczyk up the bluffs and then to within fifteen yards of the German machine gun.13

The gunner thrust his hands in the air to surrender.

“Kamerad.”

Keeping his wits about him, Spalding ordered his men to hold their fire. He needed to question the gunner, who, it turned out, was Polish. The gunner said he and his comrades had taken a vote on whether to fight and “preferred not to, but the German noncoms made them.” He swore he had not tried to kill Spalding and his men.

Sergeant Streczyk, who spoke Polish fluently, glared at the gunner with withering contempt and slapped him hard over the head. “So why were you shooting at us?”

The man was clearly lying. Spalding himself had seen him hit three of his men. The gunner looked terrified, but the Americans he had indeed tried to mow down still held their fire. And then Spalding and his platoon moved into a defile near the top of the bluffs where a medic, a private from Kentucky called George Bowen, began working on several men, sprinkling sulfa powder on their bullet wounds.

All that morning, Bowen and other surviving medics from the first wave would toil without rest, jabbing dying teenagers with morphine spikes, in some cases hunting down more supplies from abandoned kit, moving back and forth along the beach and bluffs while under fire, holding men’s hands as they cried for their mothers, saving lives. “No man waited more than five minutes for first aid,” remembered Spalding. “[Bowen’s] action did a lot to help morale.” Bowen would later be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, along with four others from Spalding’s platoon.

There was no true respite for any man who had landed with the first wave, just a minute or two to orient oneself, try to catch one’s breath, and then reload. Spalding saw a sergeant carrying a Browning automatic rifle he’d picked up off the beach, firing it from the hip at a machine gun to the west, spewing bullets at such a rate that a man carrying extra ammunition could barely keep him fed with twenty-round magazines. Then a lieutenant from G Company came over, having landed in the second wave, and used the same route up the bluffs that Spalding had taken.14 He was followed a few minutes later by Captain Joe Dawson, the lanky commander of G Company, who asked if Spalding knew where the rest of E Company was.15 Spalding said he had no idea. He still hadn’t seen any men to his right, to the west. For all he knew, he and his platoon were the only men from E Company who’d made it off the beach.

Meanwhile, a platoon sergeant set off a flare at the base of the bluffs where Spalding and his platoon had broken the trail through barbed wire and minefields. E Company’s commander, Captain Edward Wozenski, pinned down on Easy Red with dozens of others from the first wave, saw the billowing yellow smoke from the flare. “I was praying for smoke,” he recalled, “any kind of smoke.” At last, there was cause for hope, and he decided to move his men toward the smoke. He couldn’t get up the bluffs where he was—there was just too much machine gun fire from a German strongpoint. He took his trench knife and began to press the side of the blade into the backs of men lying nearby to see if they were alive. If the GI was still breathing, he rolled him over or kicked him.

“Let’s go!”16

Back on top of the bluffs, yet another German machine gunner had spotted Spalding and his platoon as they moved west, toward the E-1 draw that led to the village of Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, E Company’s planned objective. There was no retreat. Those who stayed put on the bluffs or on the beach or waded back out into the bloodied waters were shot by snipers. Yet again, Spalding prepared to attack head-on. It was best to keep moving if he and his men were to see another sunrise. Hopefully, yet again, the angels wouldn’t desert them.

ON UTAH BEACH, near strongpoint WN5, there was a direct hit on Lieutenant Jahnke’s position, and the German officer was knocked out cold. He awoke sometime later, buried in sand. He had been hit in the back by shrapnel and felt his legs being pulled. Then he could see sunlight and began to cough up sand and dirt. There was a GI pointing his M1 rifle at his face. Close by was a machine pistol, but as he tried to grab it he was kicked in the back.

“Take it easy,” said an American in a surprisingly calm voice.

Jahnke could easily have been shot, but instead the American told him to put his hands above his head. Jahnke’s Knight’s Cross dangled forlornly, damaged, from a shoelace around his ragged collar. And then he was being dragged toward the seawall and made to sit on it.

“Come over here!” ordered an American captain.

Jahnke was soon standing close to a Sherman tank.

“How many guns did you have?”

The German refused to answer.

The captain pulled out a silk map.

“Take a look at this. We’ve got it all here.”

It was true. The map showed WN5 in extraordinary detail. It was labeled UTAH.

“Utah . . . that’s a state . . . do you come from there?” asked Jahnke.

The captain laughed.

There was a loud explosion and Jahnke fell to the ground, hit in his stomach by a piece of German shrapnel. He was bleeding badly. An American crawled over to him and handed him some field dressing and offered him a Chesterfield cigarette. It tasted heavenly. Then the American was up on his feet and standing at attention. There was a general approaching. Jahnke lifted his hand to his bare head in a feeble salute.

Theodore Roosevelt raised his hand to return the salute but then dropped it, no doubt spotting Jahnke’s gray German uniform beneath the bloodstains and dirt.

Roosevelt issued an order and before long Jahnke was being marched away with survivors from his unit and then being ordered to take off his boots and socks and wade out to a landing craft. The gold-sanded beach, where skuas could usually be seen stealing fish from black-capped sandwich terns, was now littered with the refuse of war.17

Roosevelt, meanwhile, walked along a narrow road that ran behind the dunes of Utah Beach, linking causeway exits. More men were landing and getting off the beach, pressing through gaps blown in the seawall, suffering minimal casualties. Roosevelt urged the latest arrivals to get the hell inland, shouting instructions when they started off in the wrong direction. “Soldiers were everywhere,” he recalled. “Occasionally groups of prisoners would pass, disheveled, dirty, unshaven. There was the continuous rattle of rifles and machine guns.” His only sustenance was “a cake of D-ration chocolate,” but, such was his excitement, he felt no hunger, and before long he had linked up with his aide, Lieutenant Marcus Stevenson, driving Roosevelt’s assigned jeep, which he had dubbed “Rough Rider.” “Shells continually burst around us,” he recalled, “but all I got was a slight scratch on one hand.”18 Roosevelt proudly showed his minor wound to one officer.

Roosevelt then came across General Barton, the commander of the 4th Infantry Division. “While I was mentally framing [orders],” recalled Barton, “Ted Roosevelt came up. He had landed with the first wave, had put my troops across the beach, and had a perfect picture of the entire situation.” Barton had expected Roosevelt, whom he “loved,” to be killed. “You can imagine then the emotion with which I greeted him when he came out to meet me.”19

RANGER LIEUTENANT GEORGE Kerchner watched as water sloshed around his feet in his landing craft. His boots were soaked before he’d even stepped ashore. He took off his helmet. So much spray was landing in the craft that he ordered his men to start bailing with their helmets. He joined them, dipping his dark green helmet, with its red Ranger insignia stenciled on the back, into the foot-deep oily soup of salt water and vomit. Then he dumped the contents over the side of the craft as it closed on the craggy coastline of Pointe du Hoc, five miles east of Utah Beach.

Some of Kerchner’s men had been assigned the role of “monkeys,” because they were the best climbers; they would scale the cliffs first, pulling themselves smoothly up three-quarter-inch ropes attached to three-pronged steel grappling hooks. The hooks were to be fired from rocket launchers on each craft and also from the beach beneath the cliffs. The monkeys were lightly armed with just pistols or carbines. Kerchner and his 225 fellow Rangers about to land below the cliffs also had to be as mobile as possible. Their packs, machine guns, and mortars would arrive in later boats.20

Bullets stabbed the gray waters. The landing craft were now within range of German machine guns.

“Hey, boss!” shouted a Ranger. “Those jerks are trying to hit us.”21

Kerchner could see a narrow beach, less than a hundred yards away. He gave the order to fire the rockets with grappling hooks and ropes attached. “They fired in sequence, two at a time. Out of our six ropes, five of them cleared the cliff, which was a good percentage, because some of the landing craft had a great deal of trouble. Some fired too soon and the ropes were wet and they didn’t get up the cliffs.”

Kerchner hoped his craft would “run right up on the beach” and he and his men could make a “dry landing.”22 It was 7 A.M., half an hour after the Rangers had been scheduled to land. The naval gunfire aimed at Pointe du Hoc had ended almost forty-five minutes before. The Germans of Werfer-Regiment 84 who had taken cover had, in all likelihood, returned by now to their positions above the cliffs.23 The smart thing to do, if the defenders had their wits about them, would be to crawl to the grappling hooks and cut the ropes as Kerchner and his fellow Rangers scaled the cliffs.

This whole thing is a big mistake. None of us will ever get up that cliff because we are so vulnerable.

Then the ramp was down.

It was 7:09 A.M.24

“Everybody out,” shouted a British naval officer.

Kerchner looked ahead, saw that the beach had been badly cratered by heavy bombs, and guessed that the water would be just a couple of feet deep.

“Come on, let’s go!” Kerchner yelled.

Kerchner leapt into the water but quickly sank, water over his head. He had landed in a large pool. He struggled to the surface and then began to swim toward the shore. Men behind him in the landing craft jumped away from the pool, one of the many left by the massive Lancaster bombing earlier. “Instead of being the first one ashore,” recalled Kerchner, “I was one of the last ashore from my boat. I wanted to find somebody to help me cuss out the Royal Navy, but everybody was busily engrossed in their own duties so I couldn’t get any sympathy.”25

A machine gun opened fire, sounding like a piece of cloth being torn close to the ear, a frantic ripping. Two Rangers fell close to Kerchner. The bullets kept coming. He was powerless, totally exposed, armed only with a Colt .45, as useless as a kid’s peashooter. He grabbed an M1 rifle dropped by a Ranger who’d been shot dead. Enraged, he thought for a moment or two about hunting down the machine gunner, but he stayed focused on his mission: getting his men to the top of the cliff and then taking out the powerful German guns that could easily kill hundreds of his fellow Americans who had already landed on Utah and Omaha.26

Kerchner didn’t have to bark orders to get the job done. His men quickly formed up and within moments were launching more grappling hooks over the bluff edges, dodging “potato masher” grenades dropped from above, then clinging to ropes as they began to climb up the cliffs.

Some of the Rangers would never forget the sight of Staff Sergeant William Stivison, scurrying up an eighty-foot ladder fitted to the base of a DUKW, which was bobbing up and down in the waves just offshore. Like a “circus performer,” he was firing two heavy Lewis machine guns from atop the ladder as German tracer bullets looped toward him.27 Ranger Jack Kuhn’s top-secret consultation with a London ladder manufacturer that spring had paid off royally.

One of Kerchner’s men, Sergeant Len Lomell, was close to the top of the cliffs when he saw a radioman struggling to climb any higher because of a large SCR-300 radio set on his back.

“Help me,” yelled the radioman. “Help me!”

Lomell spotted another man, who was “all muscle, a born athlete, a very powerful man,” and called out to him. The athlete grabbed the radioman and pulled him toward him, the radio’s antenna whipping back and forth, visible above the cliffs.

“Get down!” yelled Lomell at the radioman. “You’re gonna draw fire on us!”

Lomell was then over the edge of the cliff, onto grass, and rolling into a large shell crater, where he came across a captain called Gilbert Baugh, E Company’s commander. “He had a .45 in his hand,” recalled Lomell, “and a bullet had gone through the back of his hand into the magazine in the grip of the .45. He was in shock and bleeding badly, and there was nothing we could do other than to give him some morphine.”

Baugh was one of three company commanders out of four in the battalion who were now out of action.28

Lomell turned to the stricken officer. “Listen. We gotta move it. We’re on our way, Captain. We’ll send back a medic. You just stay here. You’re gonna be all right.”

Lomell moved on to another shell hole, where a dozen men were cowering, out of sight of the machine gunners and snipers who were enjoying open season. Thank God for the Lancaster bombers who had cratered the entire area. From the air, the headland appeared honeycombed with holes sometimes twenty feet deep and ten yards wide, where a platoon could shelter, safe from the streams of machine gun bullets stitching the air with the dash-dash-dash of white-hot tracers, spitting from enemy strongpoints inland to the south and from the western edge of the battery. “We hadn’t counted on craters being a protection to us,” recalled Lomell. “We would have lost more men, but the craters protected us.”29

Meanwhile, below on the beach, Lieutenant Kerchner had spotted his commanding officer, Colonel Rudder, and shouted to him that Captain Duke Slater had been lost, so he was going to assume command of D Company. Rudder, just starting up a rope ladder, couldn’t have cared less and told Kerchner to get the hell up the cliffs. Scaling them was surprisingly straightforward, Kerchner recalled, a lot easier than during training in the Highlands of Scotland.

Under fire, Kerchner made it to the top of the hundred-foot cliff and was surprised when he looked ahead. The surface of Pointe du Hoc was unlike any of the diagrams or photos he had studied so carefully. It was “just one large shell crater after another.”30

German machine gun fire swept back and forth.

A Ranger officer and a private attacked a machine gun nest. A German saw the two seemingly demented Rangers running toward him—these were no gum-chewing, cowardly half-breeds, the kind of Americans depicted in Nazi propaganda.

“Bitte!” screamed the German. “Bitte! Bitte!”

The Ranger officer let rip with his tommy gun, killing the German. Then he turned nonchalantly to the private at his side.

“I wonder what bitte means?”31

Lieutenant Kerchner, meanwhile, kept advancing, trying to reach a crater before getting hit, moving as fast as he could in the direction of the battery of guns he’d been ordered to destroy if the American landings at Utah and Omaha were to stand a chance.32

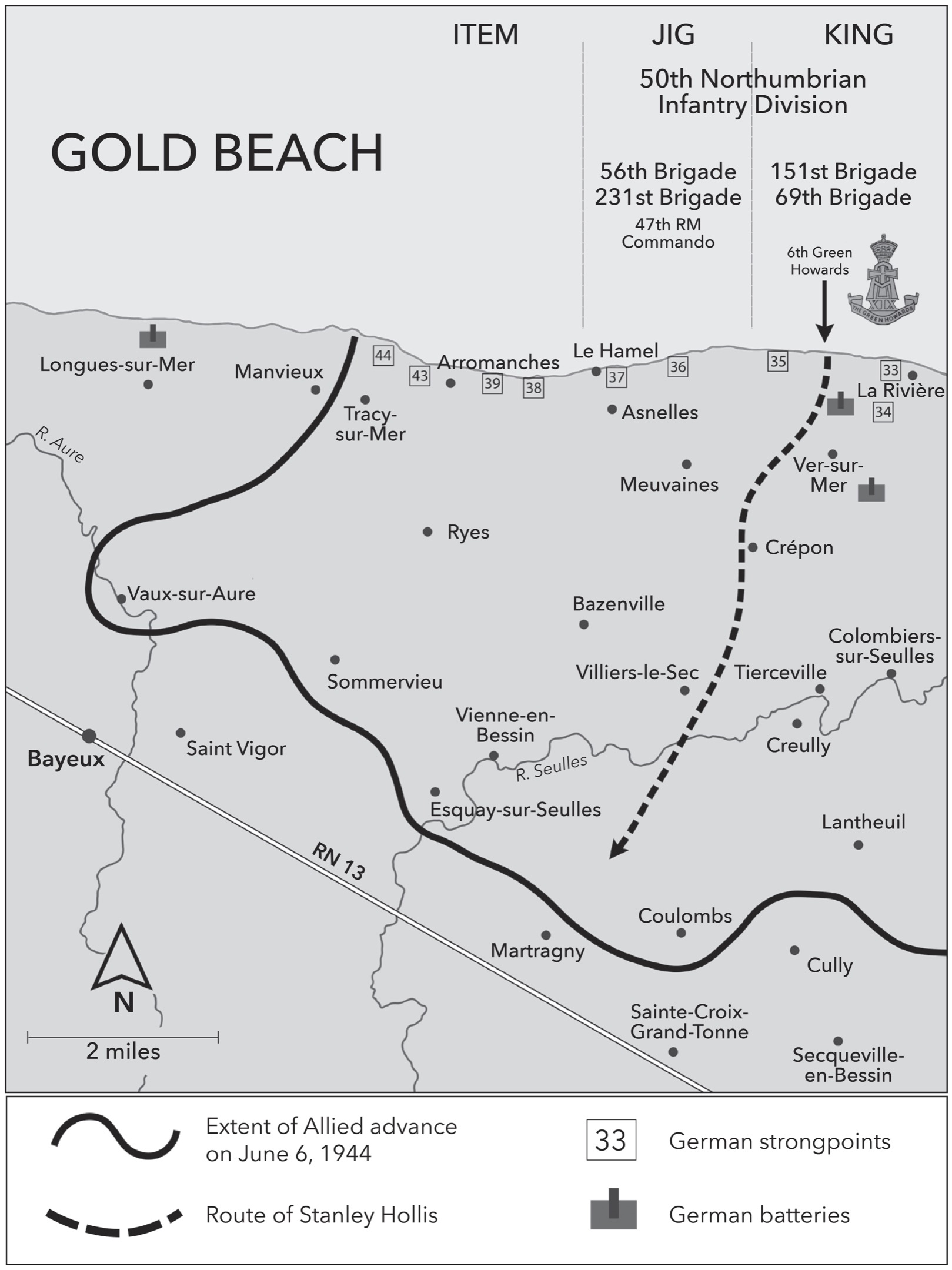

TWENTY MILES TO THE EAST, the British first wave was approaching Gold Beach, the widest of the Allied landing beaches, skirted at the western end by cliffs. The wind still blew angrily, forcing many coxswains to struggle to keep on course in the steep chop. Allied bombardment had destroyed several key defenses, but on King sector, one of two areas assigned to the British 50th Infantry Division, an 88-millimeter gun—protected by thick concrete—was causing havoc. A private in the first wave would later describe the noise as “absolutely horrendous. It’s not ‘Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang!’ It’s a continual roar of sound, constantly, without stopping.”33

As Sergeant Major Stanley Hollis stood in his landing craft as it closed on King sector of Gold Beach, he spotted what looked like a pillbox beside a railway line that ran along the beach. He lifted a heavy Lewis gun from the bottom of the craft, loaded it with ammunition, placed it on the gunwale, and opened fire on the pillbox. Then he took the Lewis gun off the gunwale. His fellow Green Howards would need it once they were ashore. “It was white-hot,” he recalled, “and I got a bloody great blister across my hand, as thick as my finger!”

A self-inflicted wound and the battle hasn’t even started.

The ramp came down and Hollis began wading through waist-deep water. A sergeant, weighed down with a pack and equipment, a few yards ahead of Hollis, dropped out of sight, having stepped into a shell hole under the water. A landing craft appeared, and Hollis saw its whirling propellers cut the sergeant to pieces as shells and mortars hissed through the air.

As Hollis ran across the beach, a tank exploded, its escape hatch spinning like a top across the sands, which appeared to stretch endlessly to the left and right. Ahead, there were no looming bluffs but a long, gentle slope of lush pasture. A German aircraft flew over, the black crosses on its gray fuselage clearly visible, and then Hollis reached some rolls of barbed wire skirting a minefield at the edge of the beach. An Irishman close by noticed several birds seated on the wire, oblivious to the raging battle—the crescendos of machine gun fire, the strangled cries and screams of the wounded and dying. Bullets whizzed by, but the birds stayed put.

“No bloody wonder,” said the Irishman. “There’s no room in the air for them!”

Hollis watched Green Howards, hunched down with mine detectors, clear a path through the minefield, laying white tape to mark a safe route, and then he and his men were stepping carefully along the trail of white tape and passing through a thick hedgerow, headed toward a gun battery at Mont Fleury, almost a mile inland, atop a rise.34

Other Green Howards were moving off the beach and inland. Some reached a house and stopped, preparing to throw grenades inside, when a Frenchwoman, in tears, emerged and pointed toward Gold Beach. “Is this the real thing?” she asked. “Is this the liberation?”35

There was the crackle of small-arms fire, like high-pitched radio static. The Irishman with Hollis was killed. It was barely five minutes after landing. Hollis pressed on, head up, running as fast as he could, sweating in his woolen uniform, knowing instinctively that it was best to be a moving target, to not stay put. He reached a crossroads, where he saw the crumpled bodies of yet more Green Howards who had been cut down by machine gun fire. He sprinted across the junction and then dropped to the ground and began to crawl uphill through a field of ripening wheat toward the Mont Fleury battery. The tall grass provided superb cover. The smell of the damp earth, of the wheat, and the occasional murmur of insects were no doubt a welcome reprieve from the din of battle and the sting in the throat from cordite and smoke.

As Hollis neared the top of the rise, the commander of D Company, Major Ronnie Lofthouse, approached him and pointed out a pillbox. The pillbox was well camouflaged, but Hollis could just make out the Germans’ gun barrels. He got up and rushed the pillbox, spraying it with bullets, “hosepipe fashion,” with his Sten gun. The Germans returned fire but missed Hollis, who was quickly on top of the pillbox, dropping a grenade through a slit, hearing its flat explosion, then jumping down and breaking through a rear entrance. Inside, he found two dead Germans and more than a dozen dazed and bloodied men who quickly surrendered to him, desperate to live.

It turned out some of the Germans were from a nearby command post for the Green Howards’ first and most critical target off the beach, the Mont Fleury gun battery, just over the brow of the rise, a couple of hundred yards ahead.36 As fast as possible, Hollis and D Company had to reach and then eliminate the guns aimed at Gold Beach and at the ships bringing in the second wave of Green Howards, due to land at 8:20 A.M.

Hollis couldn’t spare any men to escort the prisoners into captivity, so he simply gestured in the direction of the shoreline and the Germans moved off by themselves. Not long after, Hollis paused for a few moments and looked back, out to sea. The sight in particular of twenty British battleships, cruisers, and destroyers—“Force G”—filled him with new confidence, and he turned and began to lead his men forward once more, toward the Mont Fleury battery. Thankfully, a lone flail tank, one of “Hobart’s Funnies,” had cleared a path off the beach through mines and then inland toward the battery. Hollis followed its trail of stamped tracks in the crushed grass. Other flail tanks and armored bulldozers, which had landed with the first wave, had been blown up or had gotten stuck in thick mud.

At some point, a piece of shrapnel had nicked Hollis’s face, and now blood trickled down his cheeks. Fire came from yet another machine gun, a vicious ripping. Now a man possessed, Hollis reloaded his Sten gun, clipping in a new magazine with thirty-two rounds, and was attacking yet again, getting the job done, avenging the humiliation of Dunkirk and all the French women and children he’d seen so senselessly slaughtered in the city of Lille that dark spring of 1940.