CHAPTER 8

La Belle France

IT WAS 7:30 A.M. when a message went out by radio—“Praise the Lord”—signaling that Lieutenant George Kerchner and his fellow Rangers had scaled the cliffs at Pointe du Hoc. Now they had to cross the churned earth and twenty-yard-wide shell holes to reach the battery’s guns, the nearest of which were supposed to be around a hundred yards inland. Kerchner’s staff sergeant, Len Lomell, sprinted ahead of others from D Company, “charging hard and low,” hearing the crack of sniper rounds overhead and the rattle of “Hitler’s buzzsaw”—the MG42 machine gun—as he led others toward the casemates. “Nothing stopped us,” recalled Lomell. “We waited for a moment. Just a moment. If the fire lifted, we were out of that shell hole into the next one. We ran as fast as we could over to the gun positions, to the ones we were assigned to.”1

Lieutenant Kerchner followed behind. “The faster you moved,” he remembered, “the safer you felt.”2 A few dozen yards in from the cliff’s edge, he saw a German gun emplacement to his right and a gray-uniformed soldier, and he told a Ranger beside him to take out the German. The Ranger missed, firing five times without success. Not wanting to lose time, Kerchner ordered men to advance to a nearby road while he had a go at the elusive German. He couldn’t get a shot on target, either, and then the German replied with a 22-millimeter anti-aircraft gun. Its bullets could easily blow foot-wide holes in a Ranger, so Kerchner quickly ducked for cover and began crawling along a deep trench. There was an explosion from a shell landing nearby, and then a sniper fired on him as he approached men from E Company. Had they seen any men from his unit, D Company? They said some of his men were farther inland, and Kerchner set off to join them.

About a hundred yards away, two Rangers came across Number 3 casemate, one of six at Pointe du Hoc. It was a charred mass of twisted steel and smashed concrete.

“Man, the navy really did a job on them,” said one man.

“Yeah, but something’s wrong,” replied a sergeant. “There’s no gun here. Looks like the Krauts had a telephone pole sticking out to make it look like a gun. Wonder what they did with the gun?”3

A few minutes later, the sergeant found Kerchner and told him there were no guns in the casemates.

No guns? They’d gone through months of training . . . climbed those damned cliffs . . . Kerchner shrugged off the news and pushed on along the deep trench. His primary mission was over. Now to the next: setting up a roadblock on the Grandcamp–Vierville road, which ran from Pointe du Hoc to Omaha Beach, five miles to the east. The trench snaked and he couldn’t see around each turn. Would a German be waiting around the next corner?

Pointe du Hoc was a fortress with scant protection along the cliffs. The Germans had not expected an assault on the battery from the sea and so had placed minefields and strongpoints along a perimeter inland. Before long, Kerchner was closing on the perimeter and then came across some of his men. One of them was “a real fine boy” who’d been raked across his chest by machine gun fire and was dying. Other wounded lay nearby. Before Kerchner could get help to them, the Germans counterattacked, jumping from hole to hole, letting rip with Schmeisser machine pistols.

A firefight raged, feverish volleys of bullets sweeping back and forth. The Rangers managed to hold off the Germans, then Kerchner moved farther inland, coming across two men from D Company: Sergeants Len Lomell and Jack Kuhn.4 He ordered the pair to scout ahead while he and others set up the roadblock. They crept along the road and climbed through a thick hedgerow. “We came upon this draw with camouflage all over it,” recalled Lomell, “and lo and behold, I peeked over this hedgerow and there were the guns, all sitting in proper firing condition, the ammunition piled up neatly, everything at the ready.”5

The guns had been moved from their casemates to avoid damage during bombing and were now aimed at Omaha Beach.

“There’s nobody here, let’s take a chance,” said Lomell, who was carrying several thermite grenades; a few seconds later he was using them to destroy traversing mechanisms, cranks, and hinges.

“Hurry up, Len,” cried Kuhn after several minutes. “Get out of there.”

Lomell and Kuhn headed back toward Kerchner and the others from D Company, who in the meantime had set up the roadblock. “We never looked back,” Lomell remembered. “We didn’t waste a second.” The guns had been there after all. And now they were out of action. The original, critical mission for the Rangers had been accomplished. As one of Lomell’s comrades from the 2nd Ranger Battalion later put it, “Had we not been there, we felt quite sure that those guns would have been put into operation and they would have brought much death and destruction down on our men on the beaches and our ships at sea.”6

As Lomell and Kuhn crossed a hedgerow, there was a huge explosion and both were thrown through the air. Rocks, pieces of concrete, and ramrods fell all around. Dazed, they scrambled to their feet, smothered in dirt and dust, and then sprinted “like two scared rabbits” toward the roadblock D Company had set up. Was the sudden explosion from a shell fired from the USS Texas, offshore? Later they learned that a patrol from E Company had detonated a nearby ammunition store.7

Both men rejoined the remnants of D Company, under the command of Kerchner, who was delighted to hear that they’d taken out the guns: “This was the most fantastic thing that happened in the war as far as I was concerned,” Kerchner later said.8

Meanwhile, Colonel Rudder was standing at the edge of a casemate talking to some of his men when he heard the zing of a ricochet. He dropped to the ground, hit clean through the leg by a sniper’s bullet.9 A few minutes later, the battalion surgeon, Captain Walter Block, was sprinkling sulfa powder on the wound and bandaging the leg. Thankfully, the bullet had missed a major blood vessel and bone, and before long Rudder was back issuing orders. “The biggest thing that saved our day was seeing Colonel Rudder controlling the operation,” recalled one officer decades later. “It still makes me cringe to recall the pain he must have endured trying to operate with a wound through the leg. He was the strength of the whole operation.”10

A shell exploded, fired short by a British cruiser, and killed an officer and blew Rudder to the ground once more, wounding him in the upper left arm and chest. “The hit turned the men completely yellow,” recalled a young lieutenant. “It was as though they had been stricken with jaundice. It wasn’t only their faces and hands, but the skin beneath their clothes and the clothes which were yellow from the smoke of that shell—it was probably a colored marker shell.”

Despite having incurred two more wounds, Rudder continued to issue orders. Not long after the marker shell had exploded, a sergeant arrived and told Rudder that the guns were out of action.

“Ike, come over here!” Rudder ordered his communications officer, a lieutenant called Eikner. “How’s our commo working out?”

“Not too good, sir!” replied Eikner. “I’ve tried to contact the 5th Rangers and the 29th Infantry Division but can’t raise anybody.”

“Well, Ike, we’ve got to get this message out. You ready to copy?”

Eikner was ready.

“Send, ‘Located Pointe du Hoc—mission accomplished—need ammunition and reinforcements—many casualties.’ Get that out, Ike.”

Eikner relayed the message, but there was no reply. He kept trying. Finally, the Rangers atop Pointe du Hoc received a curt message from 1st Division commander General Huebner.

“No reinforcements available—all Rangers have landed.”11

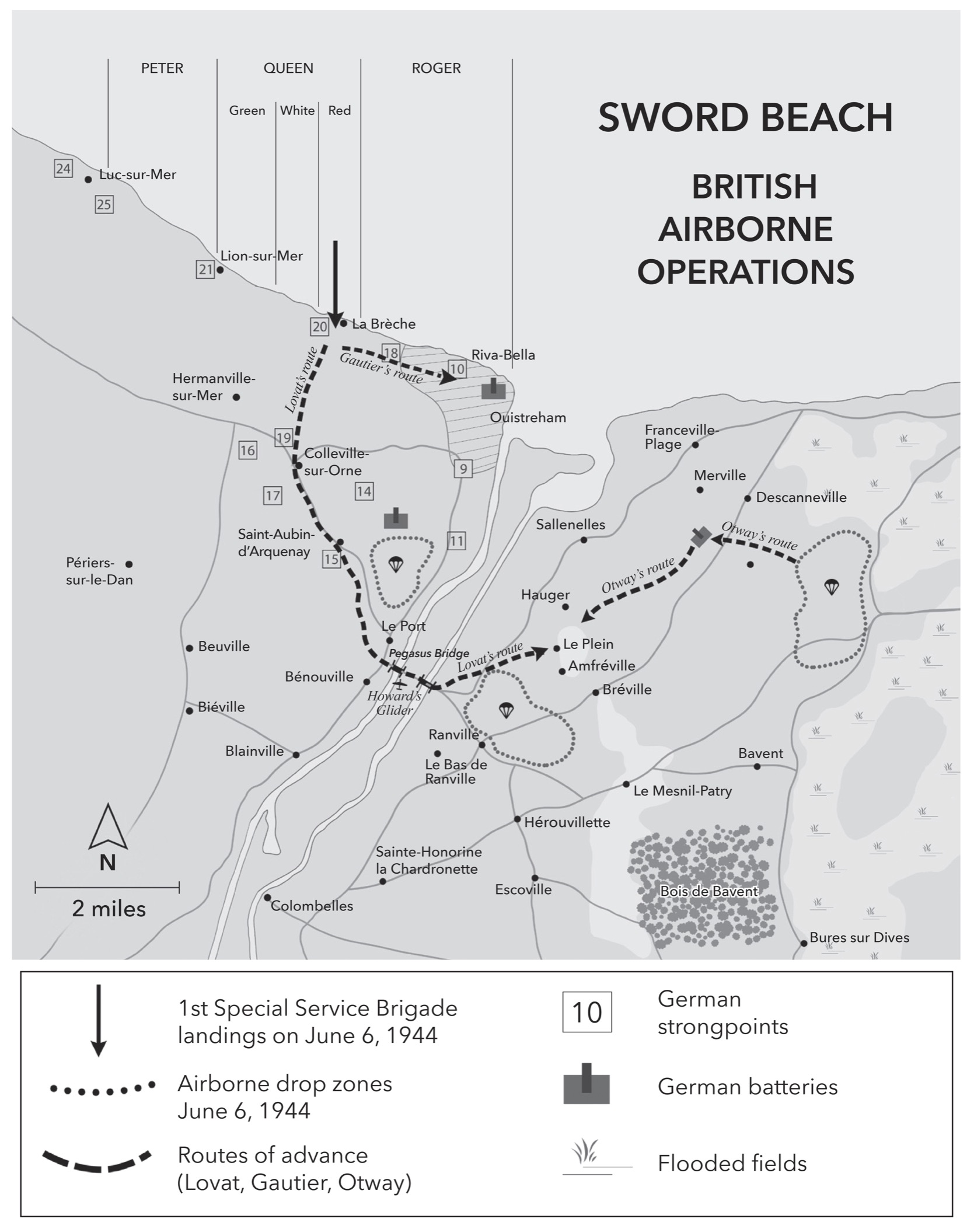

THIRTY-FIVE MILES TO THE EAST of Pointe du Hoc lay the seaside resort of Ouistreham, at the far eastern end of Sword Beach. Holiday villas had been razed to the ground along the seafront and ugly concrete bunkers and other defenses put in their place. Where French families had once basked in the sun, now some two thousand Germans from Infantry Regiment 736 manned more than eighty positions, which had met with Rommel’s approval just the week before. These positions were the target of Number 4 Commando, to which Léon Gautier and his fellow French commandos belonged.

It was past 7 A.M. and the clouds hung low and gray as the commandos approached an area known as La Brèche, around five hundred yards west of the outskirts of Ouistreham. Some of the Frenchmen had not seen the shores of their homeland since June 1940, when, like Léon Gautier, they had answered de Gaulle’s call for patriots to join him in London to fight on after France’s fall. They came from many walks of life, remembered a corporal, but all had “chosen to live among commandos and to die if necessary and be buried with the words ‘Unknown Allied Soldier’ on their graves.”12

Gautier looked across the rough seas at a landing craft, around fifty yards away, carrying some of his fellow French commandos. He could see the tall and burly figure of forty-five-year-old Commander Philippe Kieffer, mingling with his troops, giving them last words of encouragement. From farther out at sea, the battleships HMS Warspite and HMS Ramillies broke the silence with their 15-inch guns. The noise drowned out the engines on Gautier’s LCI (Landing Craft Infantry) as he looked up and saw long trails of yellow smoke streaking across the sky, from the countless volleys of rockets being fired at the landing beaches. Then the boats carrying the French commandos were pushing ahead of those filled with their British comrades. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Dawson, the commander of Number 4 Commando, which included two French troops, had decided to allow de Gaulle’s boys to go first.

“Messieurs les Français,” Dawson had ordered, echoing a famous exhortation from the eighteenth century. “Tirez les premiers!”

Men of France—shoot first!

Gautier could hear machine gun fire. He looked ahead and from the smoke emerged the ragged coastline. France looked more beguiling than ever, despite the gunfire. Men beside him were choked with pride, some near to tears. “There was no fear,” recalled Gautier. “We were just ready to do our job. When we first saw France appear out of the mist we were all emotional but very happy. One of the last things I recall was being given a tin of ‘self-heating soup.’ It was horrible. I threw it into the sea. I love most things English, but a Frenchman has to draw a line somewhere.”13

Gautier adjusted his green beret one last time.14

On y va.

Here we go.

Just before landing, Gautier checked his grenades and the ammunition for his “precise and faithful” tommy gun. He saw that the photo in his pocket of his fiancée, Dorothy, had gotten wet. Not to worry. He’d fix it later.15

From his landing craft, Commander Philippe Kieffer could now see rows of beach defenses, Rommel’s mined stakes, and, beyond on the beach itself, long rolls of barbed wire.16 “We had arrived,” recalled Kieffer. “A shock—a bump—we were aground. At this exact moment the sea bed seemed to rise in a rumble of thunder: mortars, the whistle of shells, staccato fire of machine guns—everything seemed concentrated towards us. Like lightning the ramps were thrown down.”17

Léon Gautier’s LCI, number 523, ground ashore and got stuck around a hundred yards from the sand. It was 7:30 A.M. and Gautier was standing beside his commanding officer, thirty-year-old Captain Alexandre Lofi. A somber-faced miner’s son who had joined de Gaulle’s Free French in 1940, Lofi led Troop 8 of Number 4 Commando. The English commandos had nicknamed him “Lucky Man,” because he’d always come up trumps. Now Lofi would need all the baraka—good fortune—he could get.18

“Follow me everywhere,” Lofi ordered Gautier. “I’m going to need you and your tommy gun.”19

Just before he stepped off the craft, ready to wade or swim ashore, Gautier saw a shell make a direct hit on Commander Kieffer’s craft, to his left, destroying its exit ramp and wounding several officers, including Kieffer.20 Then Gautier was wading ashore, with his tommy gun above his head. Men fell close by, cut down by shrapnel from a 50-millimeter cannon firing from a concrete emplacement on the beach. Gautier knew the cannon to be a formidable weapon, capable of firing twenty shells per minute.

In the shallows, there were appalling scenes. British troops from the East Yorkshire Regiment who had preceded Gautier and his fellow Frenchmen by a few minutes were supposed to have cleared the way but were now mostly paralyzed by fear, dead, dying, or frantically trying to dig foxholes in the sand.

A commando neared a man on the ground.

“Get up, you idiot, keep going.”21

The commando kicked the man and realized he was dead. So was a soldier beside him.

Gautier looked to his left and saw wounded men from Kieffer’s craft. They were drowning amid debris, their cries muted by the water they had swallowed. He kept going, crouched low, headed toward a stretch of sand dunes. Beyond the dunes lay a holiday camp, the rallying point for Number 4 Commando’s six hundred men.22 From the left came rapid fire and more Frenchmen began to fall. A sergeant nicknamed Pepe died quietly, his stomach sliced open, guts spilling onto the sand.

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Dawson, although wounded in the leg, hobbled from one cluster of commandos to another, urging them on, bright red blood clotting in his blond hair.

“Go boys!”23

Gautier remembered the key order he had been given in training: “Do not stop for the wounded or dead.”24

On Dawson’s boys ran.

Gautier followed Captain Lofi, who now led Troop 8 toward some barbed wire at the edge of the beach.

Dawson’s boys reached the barbed wire, which looked to one of them “like a crown of thorns covering the face of our crucified country.” A sergeant called Thubé pulled out his wire cutters and snipped a gap, and his fellow commandos ran through and into a minefield at the edge of the dunes. Five minutes before, several flail tanks had worked their way through parts of the minefield before being destroyed by German fire, but thankfully they had at least cleared some mines. The others lay buried safely beneath inches of sand swept inland by a storm the previous day. The bad weather that had caused General Eisenhower to postpone the invasion had “without doubt also saved the day,” recalled Gautier, for him and his fellow Number 4 commandos.25

Gautier followed Lofi into the relative sanctuary of the dunes, making certain to avoid moving in a straight line, to throw off German gunners. Finally, he and Lofi reached the ruins of the prewar holiday camp. They had gotten across Sword Beach and then reached their first objective on D-Day without getting hit. They were home at last.26

The assembly area was quickly full of commandos, giving the thumbs-up and smiling for a photographer as they sheltered in the lee of half-demolished brick walls, reloading, getting their heads straight for the attack into Ouistreham, dropping their heavy packs in piles so they would be able to move as fast as their legs could carry them. It would be close up and personal from now on, hand to hand, dagger to throat. The packs would be delivered to them later, once they’d kicked the Boche out of town, back to Berlin. “Things were unnaturally quiet,” recalled one commando, “after the chaotic din of the beach, which had been almost numbing in its intensity; it seemed extraordinary that we should be able to speak in a normal tone of voice here.”27

The commandos would now have to fight eastward for almost fifteen hundred deadly yards, past holiday villas with red-tiled roofs and neatly trimmed garden hedges, crouching as low as they could, then sprinting across road junctions and alongside high stone walls plastered with Nazi propaganda posters and painted with the name DUBONNET, a popular aperitif. They would head straight down the Rue Maréchal Joffre to a heavily defended blockhouse, the core of German resistance in Ouistreham, which had to be neutralized if operations in the Sword sector of the Allied landings were to succeed. It was a tough target indeed, surrounded by a maze of trenches and barbed wire and protected by anti-tank guns. The ugly concrete fortress had replaced a much-loved casino where some of Gautier’s comrades had gambled before the war.

Gautier stayed close to Lofi as he led Troop 8 past abandoned machine gun emplacements.

“Watch out, Lieutenant,” someone shouted.

There was the rip of a machine gun and a bullet holed Lofi’s trousers without wounding him.

As Gautier and the rest of Troop 8 closed in on the blockhouse in Ouistreham, German mortars opened up and several men were hit. Gautier still stuck close to Lofi, firing his tommy gun, spraying bullets. His finger pressed the trigger, over and over, as he fired on German positions. Then there was an angry shout.

“Fire single shots. Don’t waste bullets.”28

Gautier realized he’d gone through several magazines. It was time to make each round count. A German sniper aimed at one of Gautier’s comrades, Marcel Labas, and killed him as he moved along the Boulevard Maréchal Joffre. A hundred yards farther on, another shot rang out and a lieutenant called Hubert was hit in the head.

German resistance intensified, so Lofi ordered Gautier and others to take positions in the ground floors of the villas lining a road facing the blockhouse. Another group of French commandos, led by the wounded Kieffer, had made its way to the other side of the blockhouse, squeezing through a small gap in an anti-tank wall, and had also taken up positions in nearby holiday homes.

The German fire became increasingly accurate, directed by observers in a fifty-foot-high bunker some two hundred yards to the south, farther inland.

An 88-millimeter artillery piece opened up, leveling an entire house in one ground-shaking explosion.

Lofi had a feeling his position would be next.

“We’ve got to get out of this place right now,” Lofi told Gautier and others.

He was right. Three minutes later, their position was utterly destroyed.

The French had no tanks or heavy weapons capable of destroying the 88-millimeter gun. Luckily, fifty-seven-year-old Marcel Lefevre, a World War I veteran with a neatly trimmed white mustache, braved the explosions and deadly rain of shrapnel and told a French officer that he belonged to the Resistance, wanted to fight, although he was unarmed, and added that he knew where to find and then cut communications wires leading from the main blockhouse to the 88-millimeter gun and other artillery.29

The wires were severed and the German fire became less accurate, but the blockhouse still had to be taken.30 Then Commander Kieffer heard over a radio that British amphibious tanks had finally been spotted in the outskirts of Ouistreham, having cleared Sword Beach. He went in search of support and, to his men’s delight, returned riding jauntily on a tank’s turret, guiding it to the best position to fire on the blockhouse. Within thirty minutes, the blockhouse’s guns had fallen silent.

Two French civilians approached Gautier, at first mistaking him for a British soldier because of his uniform. They were far from grateful. This was just another commando raid—a hit-and-run. What would happen once they’d gone? The Germans would be back with a vengeance. Anyone found to have helped the invaders would be shot.

“We’re not leaving,” said Gautier. “This time it’s for good.”31

Colonel Dawson appeared, still bleeding from a head wound and wrapped in a blanket. “Fantastic job!” said Dawson.32 More tanks were on the way, he added.

On to the next objective. The commandos now had to link up with Major John Howard’s airborne troops holding Pegasus Bridge, six miles farther inland to the south. Gautier marched with his fellow Frenchmen back to the holiday camp where they had left their packs, marveling at the thousands of British troops now swarming across Sword Beach. Then he was heading south, walking through the village of Colleville, past gardens in full bloom.

The sun appeared from among the clouds, as if to welcome him home, and the straps on his pack bit into his shoulders as he came across bodies of British commandos who earlier had forged ahead. No one stopped to bury the dead, the contorted corpses stiffening with rigor mortis, with young faces turning a waxy yellow. Then Gautier, proudly wearing his green beret, followed his fellow commandos into the open countryside, crossing lush pasture and fields dotted with clumps of yellow cowslips and white primrose. As he headed toward Pegasus Bridge, he thanked God he was still alive. He knew he had been lucky, as the second Frenchman to put his feet on Sword Beach that morning, to survive. Bonne chance. Lucky indeed, unlike ten of his compatriots who had made the ultimate sacrifice.33

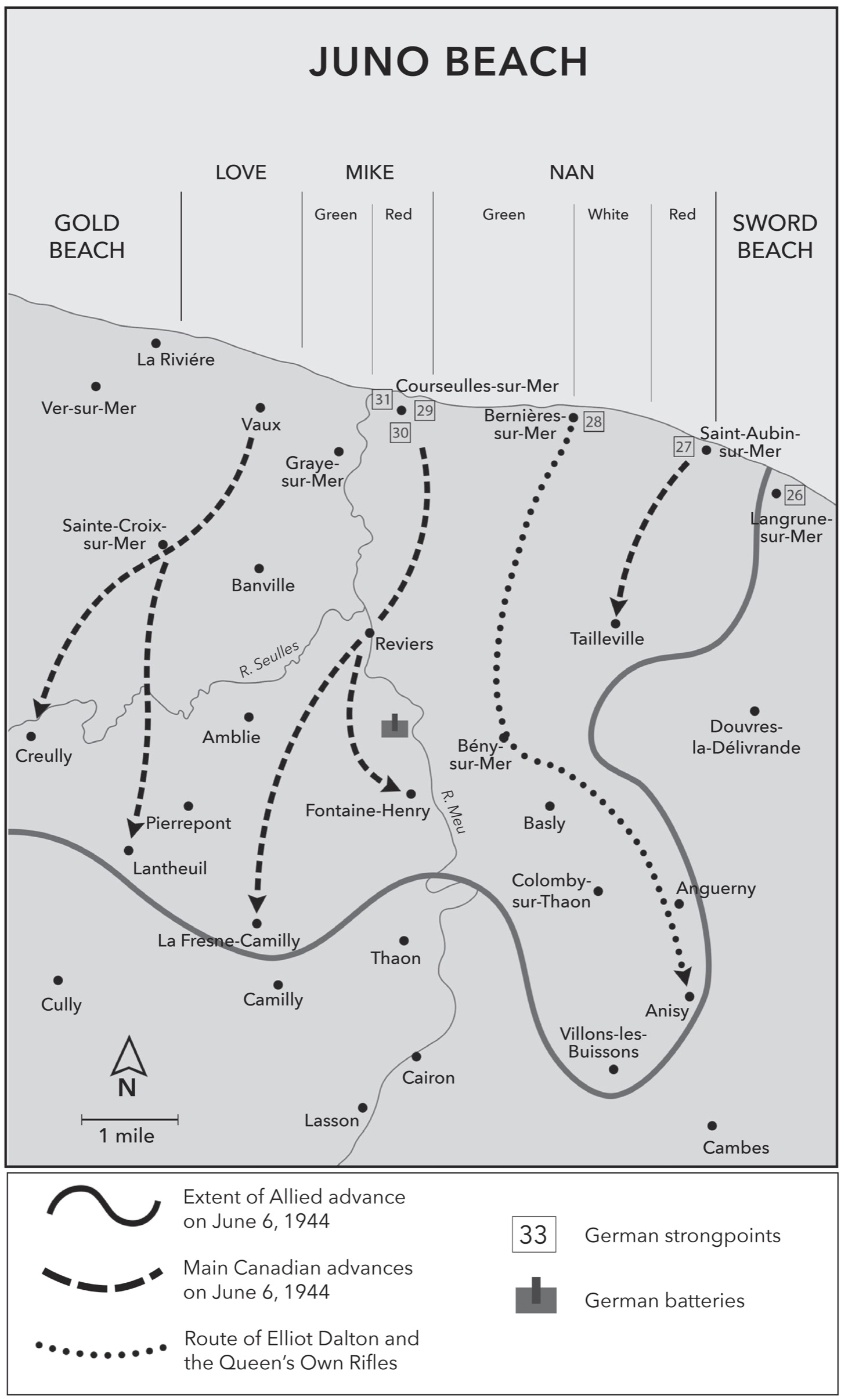

TEN MILES TO THE WEST, the first wave of Canadians from the Queen’s Own Rifles were surging toward shore. Thirty-three-year-old Major Charles Dalton, a traveling tea salesman before the war, shouldered his tommy gun and issued last orders.34 Tall and dark-haired, with a perfectly trimmed mustache and a high forehead, he was in command of the regiment’s B Company, whose D-Day target was now just visible: the “Nan White” sector of Juno Beach, which had been assigned to the Canadian 3rd Division.35

Every now and again, Charles looked to his left and saw the landing craft of A Company, plowing against the waves toward land. Remarkably, A Company was led by his younger brother, twenty-nine-year-old Elliot, the same height but with thicker eyebrows, a wider face, and a much more carefree personality. Although more distant from his men, Charles was no less respected by them than Elliot, the more handsome of the pair, unmarried and with a reputation as something of a ladies’ man. Among the entire invasion forces, they were the only brothers who were leading infantry companies that would land side by side in the first wave. They had arguably the most difficult task of all Canadian company commanders: They would assault the toughest sector of Juno, a mile-wide stretch facing the timber-and-red-brick seafront homes of the village of Bernières-sur-Mer.

The Daltons were an intensely competitive pair, whether on a tennis court in their youth or on a parade ground. “Charlie was the archetypal dashing young officer,” remembered a corporal. “He really had a lot of style. He was elegant and acted the part of a fine officer. His brother was very down to earth. We would follow him to hell if we had to.”36 Neither had seen combat, even though they had been training in England since July 1941.37 They had both wanted to command men in the first wave, even after General Bernard Montgomery visited their unit and predicted that it might suffer 80 percent casualties.

Elliot would lead his men ashore a couple of hundred yards to the east of his brother. They had tossed a coin to decide which company would go in on the right and which on the left. Their first and most important challenge was to secure key beach exits. If they failed, thousands of their countrymen, all volunteers, could be trapped and slaughtered just as they had been during the failed Dieppe raid, in August 1942—the last time a Canadian division had been sent into action in France.38

Earlier that morning, around 3:15 A.M., Charles had encountered Elliot on the deck of the heaving USS Monrovia. The brothers had stood silently at the rail, looking out into the forbidding darkness of the English Channel. Charles had reached into his mouth and pulled out an ill-fitting dental bridge, which he then threw overboard into the rough waters.

“The damn thing’s killing me,” he had told Elliot. “If I survive . . . I’ll get a new one, maybe . . .”39

It had then been time to say good-bye. “I think my brother felt there should be a farewell scene,” recalled Charles. “Something from Hamlet, maybe. Something appropriate.”

Instead, the brothers had simply shaken hands.40

“Well, good luck,” Charles had said. “I’ll see you tonight.”

“Fine, fair enough.”

It was now five hours later, just past 8 A.M., and Bernières-sur-Mer loomed ahead.41

The first wave, comprising ten assault craft, was spread out over several hundred yards. Charles’s A Company boats were to the right of Elliot’s B Company craft, all moving hesitantly, it seemed, toward the seafront village. Which brother would be first to set foot in France and claim bragging rights?

Elliot stood at the bow of his landing craft. “I was personally convinced in my own mind that no one would ever kill me,” he recalled. “My biggest fear on D-Day—I was terrified—was that I [would] not be able to lead my men properly.”42

A shell exploded and a piece of shrapnel hit one of Elliot’s men, gouging his cheek.

A crewman quickly patched the wounded man up.

“If that’s the worst you get,” said the crewman, “you’ll be lucky.”43

A few hundred yards to Elliot’s right, Charles stared at the heavily defended beach fronting Bernières-sur-Mer. Three pillboxes, around fifty yards apart, loomed in the distance, built into a seawall that ran along the seafront. Behind a large wood-framed house stood a small railway station. There was a park directly beside the house. It was bound to be heavily mined. On a clear day, Charles would have been able to see the 220-foot-tall steeple of a twelfth-century Romanesque church, L’Église Notre Dame, half a mile inland, but now the entire area was shrouded in smoke from bombing and naval fire.44

Charles thought about the last advice given by a medical officer just ten hours before: “Now look, fifty percent of you are going to be casualties. If you’re hit, one of two things will happen. If you’re dead, your problems will be over. If you’re wounded, you’re going to get better. So just lie there and keep quiet and wait for the medical people to catch up with us, but nobody else will stop to help you, because if they do the whole thing will stop.”45

In his landing craft, younger brother Elliot moved toward the coxswain.

The coxswain was slumped down.

Elliot saw blood trailing from a bullet hole in his forehead. The man had not been steering—he’d been dead awhile.46 Then Elliot heard his craft scraping against stones. It was 8:12 A.M. The first wave of Canadians had arrived at Juno Beach.

A sergeant major barked orders: “Move! Fast! Don’t stop for anything. Go! Go! Go!”47

They were down the ramp, splashing through water onto hard sand, sprinting toward the seawall. “Every single one of us,” recalled the sergeant major, “from Elliot Dalton, our commanding officer, who was the leader for his boat, and the other A Company boat leaders . . . was on the run and at top speed.”48

From every direction came obscene noise as bullets and explosions ripped the air. As Elliot crossed the beach under intense fire, he looked to his right and saw a platoon being mown down by German fire from a pillbox that, he realized, had not been shown on reconnaissance maps. In all, twenty-eight men from his company quickly lay dead or badly wounded on the beach. They had, in the laconic words of an official after-action report, “caught a packet of trouble.”49 But more than a hundred others, including Elliot, were able to get to the first protection, the seawall that curved upward to a thick skirt of barbed wire.

Meanwhile, Elliot’s brother Charles had arrived in a craft that ground ashore directly in front of a pillbox.50 The ramp came down, splashing into the rough sea.

“Follow me!”51 shouted Charles, who then stepped off the ramp into twelve feet of water, quickly disappearing as he was pulled down by the eighty-five-pound pack on his back and the ammunition strapped to him. Thankfully, he was wearing a life vest and managed to get his head above water, then waded toward the beach. A man close by was hit four times, bullets gouging his stomach and chest. It was easy to drown if wounded, or even if a man with heavy equipment on his back merely stumbled. Then Charles spotted others who had been cut down by machine gun fire from the pillbox dead center of his landing sector. Every man to his right had been killed.52 Miraculously, he had been just out of range, by a few feet, of the machine gun’s traverse.

One of his men emerged from the blood-tinged shallows and ran toward the seawall. Bullets ripped through his pack, shredding it.

“That was close.”

“Yes, there goes your lunch,” said a man nearby.

The next volley of bullets did not miss, and the man with the pack slumped down, dead. His fellow rifleman tried to take off his wristwatch and ID bracelet, mementos for his widow, but he had to pull back when more bullets came his way.53

Charles kept moving across the beach. He glanced back and was shocked to see that nobody in B Company was following him. Then he checked to the left and right: There was no sign of Elliot or his company, either. All he could see was a few soaked men, lying wounded at the water’s edge, shaking with terror, being picked off by German snipers.54

They’ve gone to ground.

He felt he had failed.

They didn’t follow me.

Charles reached the seawall near the pillbox and pulled out a grenade. It wasn’t powerful enough to blow the door off the pillbox, so he opened fire with his Sten gun instead, but his bullets ricocheted off protective shields with a pathetic clatter. He spotted a ladder, placed it against the pillbox, climbed up, and fired into a slit. Finally, the machine guns inside fell silent. But then a German officer appeared and aimed his 9-millimeter revolver, and a bullet pierced Charles’s helmet and he slid, badly wounded, stunned, down the ladder.

A medic was nearby and quickly reached Charles.55

“Sir, I thought you knew better than to do that,” said the medic, “sticking your head over the top of that wall.”56

“I wasn’t trying to be smart,” groaned Charles, “just trying to find some way to stop these people from firing . . .”57

The bullet had glanced off his skull, leaving a bloody furrow. As the medic wrapped his head in a bandage, Charles saw some of his men running toward him.

“Get up to the wall,” he shouted as blood trickled down his face.58

Around three hundred yards to Charles’s left, out of view, Elliot Dalton led his men over the seawall and onto a railroad track. Bullets snapped overhead and he called to his men, ordering them to follow him, and then he was up and running again, heading to a row of brick-faced houses, one of which held a machine gun nest. He kicked in a door, tossed a grenade, spattered a room with bullets, then moved on to the next room, reloading, and on to another house, a headquarters of some kind. “We’d been told it was a communications center for the whole sector of the beach,” he recalled. “I’d lost track of most of my men but decided to attack it anyway, just a Bren gunner, my batman and myself. The Bren gunner starts to fire at the windows and my batman and I begin to crawl up the long garden on our bellies. Halfway there this big gold ball starts to come out of a cellar window. It was a flagpole with an enormous French flag on it. I stopped the Bren gunner firing and these fifty poor French people came out of the cellar with their hands up. They were all elderly and scared to death. There were no Germans in there at all.”59

Elliot headed to a rendezvous point at the southwest of Bernières-sur-Mer. It was around 8:30 A.M. Hopefully, his brother would be among the survivors gathered there before they pressed inland to the regiment’s next objectives.60

Meanwhile, Charles had been able to get to his feet and was trying to catch up with the men from his company. A medical officer spotted the bloody bandage on Charles’s head and insisted on applying fresh dressings.

“You’ll be back in England by tonight,” said the officer.61

On the beach, not far away, a chaplain walked from one severely wounded man to another, giving last rites. “The noise was deafening,” he remembered. “You couldn’t even hear our huge tanks that had already landed and were crunching their way through the sand; some men, unable to hear them, were run over and crushed to death.”62

Each young Canadian had the letters CANADA below QUEEN’S OWN RIFLES on his upper sleeve.

The chaplain knelt beside each dying man.

“And thus do I commend thee into the arms of our Lord of earth . . .”

Among the men led by the Dalton brothers, more than a hundred lay dead or wounded, the highest loss of any Canadian unit on D-Day.63

“Our Lord Jesus Christ, preserver of all mercy and reality, and the father creator . . .”

LORD LOVAT saw some of his commandos aboard LCI 516 take a tot of rum. He’d forbidden officers from doing so, wanting them utterly clearheaded. But the lads needed something other than the dodgy breakfast of sardines and cocoa in their stomachs to settle their nerves. Then Lovat saw several burning craft, adrift and spewing oily clouds of smoke, sad casualties of the first wave. One badly damaged boat was returning slowly from Sword Beach, which looked, from Lovat’s perspective, like a narrow strip of dark sand separating the heavy skies from the sea. “The helmsman had a bandage round his head and there were dead men on board,” remembered Lovat, “but he gave us the V sign and shouted something as the unwieldy craft went by. Spouts of water splashed a pattern of falling shells.”64

Lovat’s craft picked up speed, heading for a gap among hundreds of offshore obstacles, mostly long poles with Teller mines attached. Now more buildings, their roofs holed by shellfire, and other landmarks, etched in men’s minds after months of planning and training, were clearly visible. Lovat was in the right place and on time—approaching Queen Red sector, at the center of the five-mile-long Sword Beach.65

The officer responsible for finding a route through the defenses was a New Zealander, Lieutenant Commander Denis Glover, described by a friend as “a surprising compound of poet, craftsman, wit and devil-may-care roisterer.”66 Thirty-one-year-old Glover had ordered that Mozart be played loud on a gramophone, and now, to the rousing chords of the Austrian genius and with consummate skill “running on a timetable towards terror,” he guided his hundred-foot-long LCI, carrying fifty of Lovat’s commandos, through gaps in the first belt of offshore obstacles.67 He appeared calm and collected as his passengers heard the deep rumble of enemy artillery and watched shells explode among wrecked landing craft on Sword Beach.

Within shouting distance of Glover, in LCI 519, Lord Lovat stood beside Bill Millin, who was gripping his pipes in anticipation, wearing a kilt and no underwear, his testicles exposed to the chill morning air.68 It was 8:40 A.M. as they closed on Queen Red sector, an eight-hundred-yard-wide stretch of sand, in spots littered with the corpses of men from the East Yorkshire Regiment, who had been cut down as they bunched in panic. The tide crept in behind them.69 Grievously wounded men screamed above the crash of the surf and the whine of artillery and the hacking of machine gun bullets. Others wore life jackets and clung desperately to beach obstacles as the still helmeted bodies of their mates bobbed against one another in the shallows.

Lieutenant Commander Rupert Curtis, in charge of Lovat’s LCI, spotted a large building at the eastern end of Queen Red sector of Sword Beach. He now knew he was in exactly the right place.70

“I am going in,” Curtis told Lovat.

Time slowed—the “smallest detail seemed to assume microscopic clarity,” Curtis recalled. Bullets and shrapnel gouged the sands ahead. The engines growled as he applied more power and then the craft entered shallow water. “At that moment,” remembered Curtis, “we were hit by armor-piercing shells, which zipped through [a] gun-shield but fortunately missed both gunners.”71 Thankfully, the Germans were not using high-explosive rounds. Had they done so, Curtis later recalled, “many of us would have blown up on the beach, for we carried four thousand gallons of high-octane petrol in non-sealing tanks.”72

The landing craft was in three or four feet of water.

Sand scraped against the bottom.

“Stand by with the ramps!”

Four sailors moved to lower the exits.

Oiled chains clattered.

“Lower away there.”73

Bill Millin looked utterly miserable—he had been violently seasick for several hours—as he clutched his bagpipes. Lovat clambered down a ramp and leapt into the water. Millin, shorter than the six-foot Lovat, waited a second or so to see how deep the water was before he followed. A man on a ramp tumbled into the water, shot dead, and Millin decided not to hang about a moment longer, jumping into the surf. Immediately, his kilt rose to the surface and he felt the shock of cold water. But this made his seasickness vanish and, although men were dying all around him, he was aware only of finally having his feet on terra firma and of feeling immensely relieved to be off the heaving landing craft.

Millin followed the slender figure of Lovat, wading ahead of him, trailing a line of commandos snaking toward one of several tanks that had already been landed, some of them equipped with strands of metal flails for destroying mines. Amid the smoke a hundred yards ahead loomed a large three-story building, a key landmark that looked as if it had barely been touched by shelling.

Millin, remembering his orders, inhaled, pursed his lips, and blew into the tartan bag of his pipes as he, too, headed for the bullet-whipped sands.

Even amid the hue and cry of war, Lovat heard the unmistakable skirl of “Hieland Laddie” and turned toward Millin to show his approval.74

The cold water now numbed Millin’s testicles and lifted his red-squared kilt around his waist like a ballerina’s tutu.75 He finished playing “Hieland Laddie,” giving every man’s heart a lift.76

Lovat was only a couple of yards ahead of Millin when he heard him start on another tune. “The water was knee-deep when Piper Millin struck up ‘Blue Bonnets,’” he recalled, “keeping the pipes going as he played the commandos up the beach. It was not a place to hang about in, and we stood not on the order of our going. That eruption of twelve hundred men covered the sand in record time . . . As we ran up the slope, tearing the waterproof bandages off weapons, the odd man fell, but swift reactions saved casualties.”77

Lovat suddenly noticed, amid the noise and chaos, that Millin had stopped playing his pipes.

“Would you mind giving us a tune?” asked Lovat.78

“Well, what tune would you like, sir?”

“How about ‘The Road to the Isles’?”

“Would you want me to walk up and down, sir?”

“Yes. That would be nice. Yes, walk up and down.”

It seemed a “ridiculous” idea to Millin. They were now under intense shellfire. Standing around playing the bagpipes was sheer bloody madness.

Lovat was being ridiculous, but he was not a man to be crossed.

I might as well be ridiculous as well.

The beach was “cluttered with tanks and armored vehicles,” remembered one man, “and it was not exactly a health resort, for it was swept by intermittent volleys of mortar bombs, machine gun and sniper fire.”79 Already lying dead on the beach were more than two hundred men from the East Yorkshire Regiment, which had been tasked with clearing the way for the first wave of commandos.80 Millin saw some “lying face down in the water going back and forwards with the surf. Others to my left were trying to dig in just off the beach. Yet when they heard the pipes, some of them stopped what they were doing and waved their arms, cheering.”81

Some were not amused.

Millin felt someone’s hand on his shoulder.

“Listen, boy.”82

Millin recognized a sergeant.

“What are you fucking playing at? You mad bastard! You’re attracting all the German attention. Every German in France knows we’re here now, you silly bastard.”83

The sands trembled from yet more mortar explosions as Millin walked back and forth along the beach three times, and then caught up with Lovat. Men were running, bent down, then flinging themselves to the ground behind the nearest cover, a pillbox just beyond the beach that had been taken single-handedly by one of Lovat’s best young men, a skinny lad known as “Muscles” who Lovat believed should have received the highest award for his courage that morning.

Captain Max Harper Gow scrambled behind Lovat. “We crouched beneath the eighty-pound Bergen rucksacks and, we hoped, beneath the flak the enemy were hurling at us,” recalled Gow. “When we reached the sand-dunes at the top of the beach I looked up and saw Lovat standing, completely at ease, taking in the scene around him.”84

Nearby, a Jewish commando named Peter Masters, who had escaped Nazi Austria and was serving in the British Army, was interrogating two POWs.

“Oh, you are the chap with the languages,” said Lovat. “Ask them where their mortars and their howitzers are.”

Masters, who was born with the name Arany but had it changed in case of capture, duly did so. There was no reply from either prisoner, and other commandos began to gather around.85

“Look at that arrogant German bastard,” someone said. “He doesn’t even talk to our man when he’s asking questions.”86

Masters realized that the prisoners were not German; they were Russian and Polish. Remembering that many Poles learnt French at school, he switched languages. One of the prisoners began to talk.

Lovat stood a few yards away, listening carefully. He spoke far better French than Masters and quickly took over the interrogation. Then he “turned on his heel,” remembered an officer, and “led Brigade HQ inland towards Pegasus Bridge and, as it happened, slap through a wired-off area, clearly marked minefields. We followed literally in his footsteps.”87 There was no time, as Lovat put it, to “play grandmother’s footsteps.” He and his men moved fast, blowing paths with Bangalore torpedoes through the areas surrounded by wire and marked with signs showing a skull and crossbones and the words ACHTUNG MINEN!88

Lovat came across one of his officers lying against a pack, shot in the heart.

“He’s dead, sir,” cried a man near Lovat, tears running down his cheeks. “He’s dead. Don’t you understand? A bloody fine officer.”

Medics tended to the wounded, including a redheaded man who had been shot in the legs and carried off the beach by a burly Scotsman.

“To think they could miss a big bugger like you,” said the redhead, “those fucking Germans . . .”89

Lovat sprinted across a road and then a railway line. Smoke lifted. Open country lay beyond. He was three hundred yards inland. He had breached Hitler’s famed Atlantic Wall, the series of concrete bunkers, pillboxes, coastal batteries, and other defenses stretching all the way from Norway to Spain. After the uproar and numbing clatter of the beach, the open fields seemed an oasis of silence. Men felt the difference intensely, as if going from hot water to ice cold.

An officer nearby looked at his watch.

“That round lasted eleven minutes.”

Lovat paused as an aid post was set up, and then several wounded men arrived. He was called to a radio. One of his finest officers, Lieutenant Colonel Derek Mills-Roberts, leading Number 6 Commando, had good news.

“Sunray calling Sunshine. First task accomplished. Report minor casualties. Now on start line regrouping for second bound. Moving left up fairway on Plan A for Apple. Still on time. Do you read me? Over.”90

Lovat read him loud and clear.

There was less pleasing news, too. Lovat now learned that Colonel Dawson, leading Léon Gautier’s Number 4 Commando, had been wounded in the leg and head.91 Commander Kieffer had also been hit badly in his left thigh by a mortar fragment but was struggling on.92

Lovat checked the time. He knew that Major John Howard’s men had successfully seized the Orne bridges, which were intact. The challenge now was to reach Howard, some six miles away, as soon as possible.93 If he didn’t make it, Howard and his men would be done for.

IT WAS AROUND 9 A.M. when the remnants of Lieutenant Colonel Terence Otway’s unit, having left the rendezvous at the calvary cross, moved into the outskirts of a village called Le Plein, on the northern end of a ridge that overlooked the Orne River. Otway was following behind several scouts when one of them spotted two French prostitutes sauntering down the road toward them. “I should imagine they’d been up to the German barracks and were on their way home,” recalled one of Otway’s men. “They’d got painted legs, short skirts. Frightened me more than the Germans!”

A corporal told the women to run to safety.

“Arse off, get out of the way.”

The women moved off, laughing. A vast army of new clients, armed with condoms, had just arrived.

The scouts carried on.

Two Germans riding bicycles appeared around a corner.

The scouts stared in disbelief.

“Well shoot the bastards then!” someone cried.

A man opened fire, killing one German and hitting the other in the shoulder.

“Hier, Doktor,” cried the wounded German, “hier, Doktor.”94

Otway advanced once more, moving farther into Le Plein.

A Frenchman wearing a distinctive blue suit walked over to Otway and greeted him.

“A very good morning.”

The Frenchman asked if Otway would like to stop by his home for a coffee when the fighting was over. Before Otway could respond, Germans nearby opened fire. The Frenchman stood with “not a care in the world,” smoking a pipe, looking down at Otway as he took cover in a ditch.95

The firefight ended and Otway sent a patrol ahead to probe the German defenses in Le Plein, but the patrol was forced to retreat and its leader was killed—clearly the Germans held the village in force. With the remnants of his battalion, Otway decided to head instead to the elegant Château d’Amfreville, less than a mile away, where he planned to set up a temporary base and wait to be relieved by Lord Lovat and his men of the 1st Special Service Brigade.96

How long would Lovat’s commandos take to reach him? An hour or several? Otway knew he would be in serious trouble if the Germans managed to deploy an armored force anytime soon. Yet such a counterattack was inevitable. Whoever controlled a ridge east of the Orne would decide the opening chapter of the Battle of Normandy in the British sector. At all costs, the Germans must be prevented from setting up artillery and moving panzers into the woods running along the high ground. If they did so, they would be able to destroy the entire eastern flank of the Allied invasion.

AS OTWAY and his men made their way toward Amfreville, the leader of the Third Reich was finally awoken at the Berghof, Adolf Hitler’s home in the Bavarian Alps. Despite the flood of news from the Normandy front throughout the night, none of his flunkies had dared wake the Führer, knowing he would be furious if he slept less than five hours; he had gone to bed at 4 A.M. with his mistress, Eva Braun, as was often his habit. But finally General der Artillerie Alfred Jodl decided enough was enough. Hitler had to be informed of the invasion.

Before long, the Führer was standing in his dressing gown, being briefed about the invasion. He appeared to be delighted, relieved that the waiting for the inevitable Allied assault was finally over.

“The news couldn’t be better,” Hitler exclaimed. “As long as they were in Britain we couldn’t get at them. Now we have them where we can get at them!”

Hitler did not believe, however, that the landings in Normandy were anything but a diversion. “This is not the real invasion yet,” he insisted.97 The major assault was still to come, at the Pas-de-Calais, where the English Channel was at its narrowest and where there were key ports, such as Calais and Boulogne.

Luckily for the Allies, the general entrusted with repelling the invasion in Normandy, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, was now nowhere near the landing beaches but instead hundreds of miles away, dressed in a red-striped dressing gown, at his home in Herrlingen, having decided to visit his wife to celebrate her fiftieth birthday. Not long after Hitler learned of the invasion, Rommel, too, was informed.

“How stupid of me.”

If only he had stayed in Normandy. He would not have hesitated, as others had, to deploy all the forces that could be mustered. The one division that could have quickly inflicted serious damage, easily mopping up Otway’s meager force and stopping Lord Lovat in his tracks, was the 21st Panzer Division, based around Caen. It had finally been released, but far too late. It would be midafternoon before the division moved in strength against British forces north of Caen, losing seventy out of 124 tanks but nonetheless preventing the seizure of the city, a vital Allied objective on D-Day.98

Dressed in a dark leather coat, Rommel was soon racing back to Normandy in a black Horch.

“Do you know,” he told an aide, “if I was commander of the Allied forces right now, I could finish off the war in fourteen days.”99