CHAPTER 1

June 5, 1944

THE CLOCK IN THE WAR room at Southwick House showed 4 A.M. The nine men gathered in the twenty-five-by-fifty-foot former library, its walls lined with empty bookshelves, were anxiously sipping cups of coffee, their minds dwelling on the Allies’ most important decision of World War II. Outside in the darkness, a gale was blowing, angry rain lashing against the windows. “The weather was terrible,” recalled fifty-three-year-old Supreme Allied Commander Dwight Eisenhower. “Southwick House was shaking. Oh, it was really storming.”1 Given the atrocious conditions, would Eisenhower give the final go-ahead or postpone? He had left it until now, the very last possible moment, to decide whether or not to launch the greatest invasion in history.

Seated before Eisenhower in upholstered chairs at a long table covered in a green cloth were the commanders of Overlord: the no-nonsense Missourian, General Omar Bradley, commander of US ground forces; the British General Bernard Law Montgomery, commander of the 21st Army Group, casually attired in his trademark roll-top sweater and corduroy slacks; Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, the naval commander who had orchestrated the “miracle of Dunkirk”—the evacuation of more than 300,000 troops from France in May 1940; the pipe-smoking Air Chief Arthur Tedder, also British; Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, whose blunt pessimism had caused Eisenhower considerable anguish; and Major General Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s chief of staff.

A dour and tall Scotsman, forty-three-year-old Group Captain James Stagg, Eisenhower’s chief meteorologist, entered the library and stood on the polished wood floor before Overlord’s commanders. He had briefed Eisenhower and his generals every twelve hours, predicting the storm that was now rattling the windows of the library, which had already led Eisenhower to postpone the invasion from June 5 to June 6. Then, to Eisenhower’s great relief, he had forecast that there would, as he had put it with a slight smile, “be rather fair conditions” beginning that afternoon and lasting for thirty-six hours.

Once more, Stagg gave an update. The storm would indeed start to abate later that day.2

Eisenhower got to his feet and began to pace back and forth, hands clasped behind him, chin resting on his chest, tension etched on his face.

What if Stagg was wrong? The consequences were beyond bearable. But to postpone again would mean that secrecy would be lost. Furthermore, the logistics of men and supplies, as well as the tides, dictated that another attempt could not be made for weeks, giving the Germans more time to prepare their already formidable coastal defenses.

Since January, when he had arrived in England to command Overlord, Eisenhower had been under crushing, ever greater strain. Now it had all boiled down to this decision. Eisenhower alone—not Roosevelt, not Churchill—had the authority to give the final command to go, to “enter the continent of Europe,” as his orders from on high had stated, and “undertake operations aimed at the heart of Germany and the destruction of her armed forces.”3 He alone could pull the trigger.

Marshaling the greatest invasion in the history of war had been, at times, as terrifying as the very real prospect of failure. The last time there had been a successful cross-Channel attack was 1066, almost a millennium ago. The scale of this operation had been almost too much to grasp. More than 700,000 separate items had formed the inventory of what was required to launch the assault. Dismissed by some British officers as merely a “coordinator, a good mixer,” the blue-eyed Eisenhower, celebrated for his broad grin and easy charm, had nevertheless imposed his will, working eighteen-hour days, reviewing and tweaking plans to launch some seven thousand vessels, twelve thousand planes, and 160,000 troops to hostile shores.

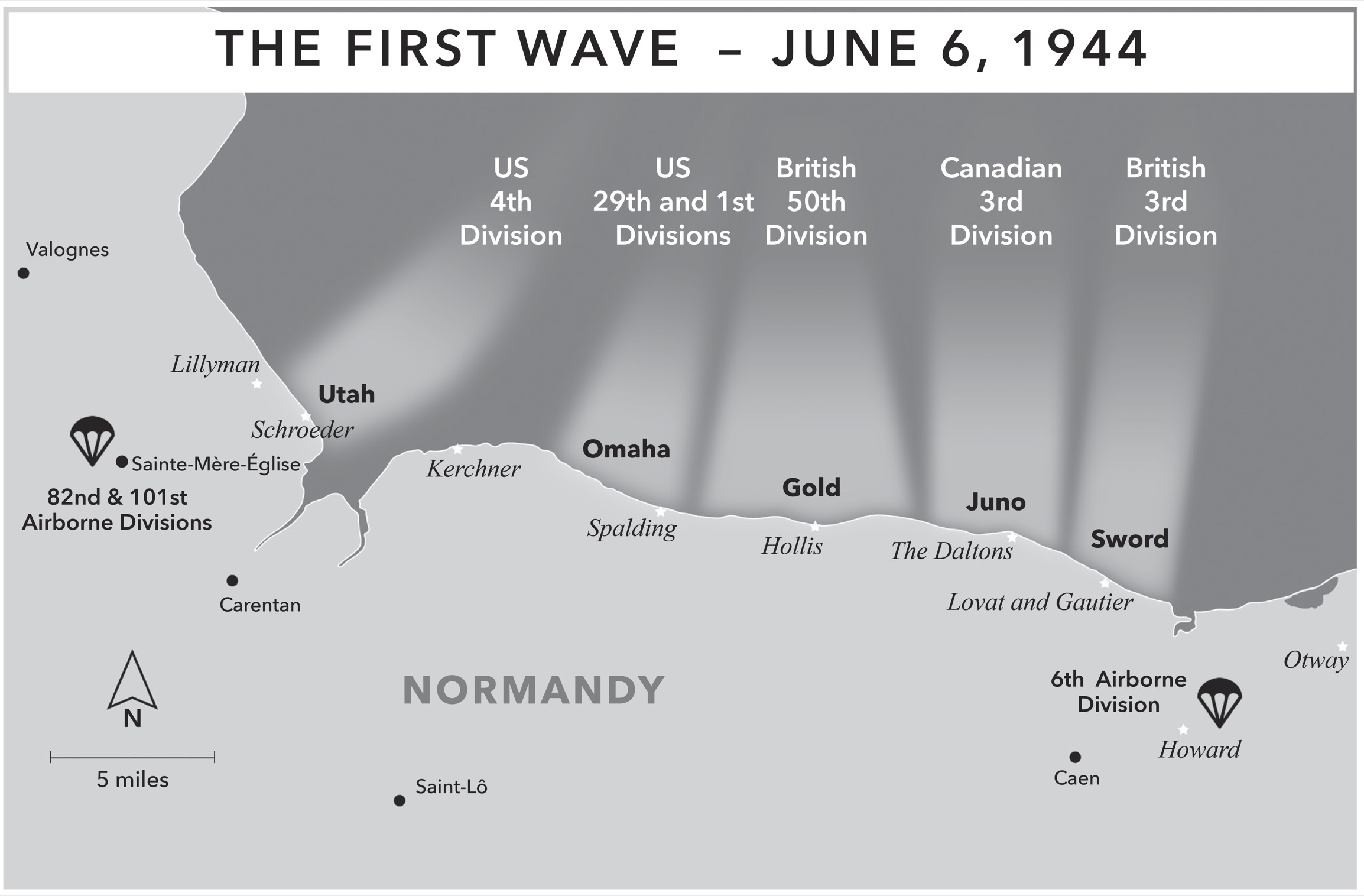

Eisenhower had overseen vital changes to the Overlord plan. A third more troops had been added to the invasion forces, of whom fewer than 15 percent had actually experienced combat. Heeding General Montgomery’s concerns, Eisenhower had ensured that the front was broadened to almost sixty miles of coast, with a beach code-named Utah added at the base of the Cotentin Peninsula, farthest to the west. It had been agreed, after Eisenhower had carefully managed the “bunch of prima donnas,” most of them British, who made up his high command—the men gathered now before him—that the attack by night should benefit from the rays of a late-rising moon.

In addition, it was decided that the first wave of seaborne troops would land at low tide to avoid being ripped apart by beach obstacles. An elaborate campaign of counterintelligence and outright deception, Operation Fortitude, had hopefully kept the Germans guessing as to where and when the Allies would land, providing the critical element of surprise. Hopefully, Erwin Rommel, the field marshal in charge of German forces in Normandy, had not succeeded in fortifying the coast to the extent that he had demanded. Hopefully, the Allies’ greatest advantage—their overwhelming superiority in air power—would make all the difference. Hopefully.

Not even Eisenhower was confident of success. “We are not merely risking a tactical defeat,” he had recently confided to an old friend back in Washington. “We are putting the whole works on one number.”4 Among Eisenhower’s most senior generals, even now, at the eleventh hour, there was precious little optimism.

Still pacing, Eisenhower thrust his chin in the direction of Montgomery. He was all for going. So was Tedder. Leigh-Mallory, ever cautious, thought the heavy cloud cover might prove disastrous.

Stagg left the library and its cloud of pipe and cigarette smoke. There was an intense silence; each man knew how immense this moment was in history. The stakes could not be higher. There was no plan B. Nazism and its attendant evils—barbarism, unprecedented genocide, the enslavement of tens of millions of Europeans—might yet prevail. The one man in the room whom Eisenhower genuinely liked, Omar Bradley, believed that Overlord was Hitler’s “greatest danger and his greatest opportunity. If the Overlord forces could be repulsed and trounced decisively on the beaches, Hitler knew it would be a very long time indeed before the Allies tried again—if ever.”

Six weeks before, V Corps commander General Leonard Gerow had written to Eisenhower outlining grave doubts, even though it was too late to do much to alter the overall Overlord plan. It was distressingly clear, after the 4th Division had lost an incredible 749 men—killed in a single practice exercise on April 28 on Slapton Sands—that the Royal Navy and American troops were not working well together. Apart from the appallingly chaotic practice landings—the woeful yet final dress rehearsals—the defensive obstacles sown all along the beaches in Normandy were especially concerning.

Eisenhower had chided Gerow for his skepticism. Gerow had shot back that he was not being “pessimistic” but simply “realistic.”5 And what of the ten missing officers from the disaster at Slapton Sands who had detailed knowledge of the D-Day operations, the most important secret in modern history? They knew about “Hobart’s Funnies,” the assortment of tanks specially designed to cut through Rommel’s defenses—including flail tanks that cleared mines with chains, and DUKWs, the six-wheeled amphibious trucks that would take Rangers to within yards of the steep Norman cliffs—and they knew exactly where and when the Allies were landing. Was it really credible to assume that the Germans had not been tipped off, that so many thousands of planes and ships had gone unseen?

Even Winston Churchill, usually so ebullient and optimistic, was filled with misgivings, having cautioned Eisenhower to “take care that the waves do not become red with the blood of American and British youth.”6 The prime minister had recently told a senior Pentagon official, John J. McCloy, that it would have been best to have had “Turkey on our side, the Danube under threat as well as Norway cleaned up before we undertook [Overlord].” The British Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, chief of the Imperial General Staff, had fought in Normandy in 1940 before the British Expeditionary Force’s narrow escape at Dunkirk. Just a few hours earlier, he had written in his diary that he was “very uneasy about the whole operation. At the best it will fall so very, very far short of the expectation of the bulk of the people, namely all those who know nothing about its difficulties. At the worst it may well be the most ghastly disaster of the whole war!”

No wonder Eisenhower had complained of a constant ringing in his right ear. He was almost frantic with nervous exhaustion, but he dared not show it as he continued now to pace back and forth, lost in thought, listening to the crackle and hiss of logs burning in the fireplace. He could not betray his true feelings, his dread and anxiety.

The minute hand on the clock moved slowly, for as long as five minutes according to one account.7 Walter Bedell Smith recalled, “I never realized before the loneliness and isolation of a commander at a time when such a momentous decision has to be taken, with the full knowledge that failure or success rests on his judgment alone.”8

Eisenhower finally stopped pacing and then looked calmly at his lieutenants.9

“OK. We’ll go.”10

THE SHADOWS WERE LENGTHENING at North Witham airfield when an officer stepped down from a C-47 plane, a small case attached to his right wrist. Armed guards who usually patrolled the airfield, which lay a hundred miles north of London, accompanied the officer into a building where he was met by twenty-eight-year-old Captain Frank Lillyman, a slightly built New Yorker who could often be found with a wry smile and an impish glint in his eye but was now all business.

The officer opened the small case and pulled out a message and handed it to Lillyman, who since December 1943 had commanded the 101st Airborne’s pathfinders. At last, after weeks of growing tension and restless anticipation, the top-secret orders from the division commander, General Maxwell Taylor, had arrived—D-Day was on. The drop was a go. “Get the men ready,” Lillyman told a sergeant, and then the message was burnt.11

Lillyman’s men assembled at a flight line where they began to strap on their silk parachutes. Having watched a 1939 film about the legendary Apache warrior Geronimo, some had shaved their scalps, leaving an unruly strip of hair across their heads. They were all volunteers, many of them cocky misfits busted down the ranks for bad behavior, or, as one of them put it, “a bunch of good guys who had screwed up one way or another.”12 For all their past faults, none doubted that they now belonged to an elite group that had been superbly trained; Lillyman had rejected three out of four applicants, disappointing some unit commanders who thought they had gotten rid of troublemakers.13

Out of nowhere, it seemed, there appeared grinning Red Cross girls with hot coffee, a gaggle of cooing press photographers, a Signal Corps cameraman using rare color film, and several members of the 101st Airborne’s top brass, all present to witness the departure of the very first Americans to fight on D-Day, the spearhead of the Allied invasion.

There was playacting for the cameras, followed by nonchalant waves and friendly punches to buddies’ shoulders. A paratrooper riding a children’s bicycle did circles in front of a plane to much laughter. Then a medic gave Lillyman’s chain-smoking pathfinders “puke” pills in small cardboard boxes to combat airsickness, and bags to vomit into. Some threw the pills away, not trusting them, wanting to be sharp, clearheaded, the moment they touched the ground in France.

There was the guttural coughing of engines as the C-47s started warming up, and the horsing around came to an end. Lillyman’s men clambered or were helped aboard the twin-propped aircraft, which had been hastily daubed with black and white “invasion” stripes—the colors of Operation Overlord. Brown masking paper covered some areas of the fuselage to prevent damage from the still drying paint.14 To preserve secrecy, the stripes had been added to thousands of planes in a matter of hours, consuming a hundred thousand gallons of precious paint and twenty thousand paintbrushes.15

Captain Lillyman took his place beside the door of one C-47, his customary stogie between his lips, wearing white leather gloves, a tommy gun strapped to his left leg just above the M3 trench knife (useful for slitting throats) attached to his shin. He would be the first American to leap into the darkness over Normandy—if he made it to the drop zone. None of the pathfinder aircraft were armed, and none had any protection against anti-aircraft fire, and there would be no escort to defend against enemy fighters. Once airborne, Lillyman and his men would be all on their own.

IT WAS EARLY evening as thirty-one-year-old Major John Howard and his men from D Company of the Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry arrived at RAF Tarrant Rushton, in Dorset, where six Horsa gliders awaited them, chalk-marked with the numbers 91 to 96. Howard noticed the wind was up and there was some rain, but the sky seemed to be clearing in parts. A half-moon was just visible in the gathering gloom. The trucks carrying him and his 140 men rolled along a runway and were greeted by women belonging to the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, who wished them luck, some with tears dripping down their cheeks.

A sprightly, dark-haired Londoner with a wisp of a mustache, armed with a pistol and a Sten gun, Howard was a rarity among field commanders of Britain’s elite forces on D-Day: He was dyed-in-the-wool working class. The eldest of nine children, the son of a barrel maker who had fought in the trenches in Flanders in World War I, he’d joined the army to escape unemployment during the Great Depression. Cruelly turned down for a commission, he’d left His Majesty’s armed forces, angry and dejected, to become a police officer before rejoining upon the outbreak of war.

Howard still felt the sting of rejection from a decade before. Even though he had risen steadily through the ranks since 1939, he was still acutely aware of his lowly status in the British caste system, at its most hierarchical in the military. And although he had drawn high praise from superiors, he had yet to prove himself as a leader in combat. He had never killed or even been shot at. In just a couple of hours’ time, he’d have the perfect opportunity to show his mettle under extreme duress.

Howard was pleased to see the Horsa pilots awaiting him and his men.16 Before long, the pilots were chatting away with his troops, using first names, casually sharing cigarettes. Hot tea was passed around, and Howard watched as his men, their faces blackened with burnt coke, checked their weapons and gear. Some had coal-black hands, having stuck them into truck exhaust pipes and smeared the soot on their pale cheeks.

“Your face isn’t black enough,” Howard told one man. “You’ve got to get more on.”17

Just two days earlier, the commander of all Allied ground forces on D-Day, General Bernard Montgomery, had visited Howard. “Get as many of the chaps back as you can,” he told the major. Montgomery asked if Howard thought he could pull off Operation Deadstick. Could his men seize a bridge across the Caen Canal, code-named Pegasus Bridge, and one across the Orne River, four hundred yards farther east, in just a few minutes? Both bridges were crucial objectives, essential to securing the eastern flank of the D-Day landings; were German tanks able to cross those bridges, the consequences for the Allied landings could be devastating. The bridges had to be taken in a bold coup de main operation—so quickly that the Germans would be left stunned, flat-footed and unable to react in time.18

That was the easy part. The bridges then had to be held until commandos under Brigadier Lord Lovat arrived from Sword Beach. Only then could Howard and his men move to their final objective: higher ground a few miles even farther east, running from the village of Le Hauger to Escoville. This ridge had to be held with other 6th Airborne troops and then defended against what were bound to be fierce counterattacks by German armored forces. If the high ground remained in German hands, Rommel’s panzer forces and artillery would be able to fire down relentlessly on exposed British positions.

The plan for Operation Deadstick, rehearsed a total of forty-three times in the previous few months, had been approved on high, but it was essentially Howard’s own design. He’d assured Montgomery that it would succeed, but of course there was no way of knowing. In war, as the famous Prussian general Helmuth von Moltke had once declared, and as Montgomery himself had learnt in North Africa, no battle plan survives first contact with the enemy.

THE COMMANDOS of the 1st Special Service Brigade gathered their kit in a field near Southampton. Their commanding officer, Lord Lovat, watched as they packed Bren and Sten gun ammunition and stuffed their Bergen rucksacks full, “belting up amid the dust.” Some men wore their green berets at jaunty angles.

Lovat had no time for any kind of slacking or ineptitude, and as a result his commandos were “probably as perfect a fighting force as could be found anywhere,” recalled one officer.19 Those who served under him remembered a debonair and romantic leader. Lovat had a neat mustache, dark, curly hair, and “long, tapering hands.”20 He was a masterful battle planner, utterly “at ease under fire,” and at times a “terrifying” disciplinarian. Known to friends as “Shimi” Lovat, the thirty-two-year-old Oxford graduate had spent just three days in combat since March 1941, but such was the drama, panache, and success of the three commando raids he had conducted that he was already a legend among his troops.

Standing before men from 45 Commando Royal Marines and Commandos number 3, 4, and 6, Lovat addressed his troops for the last time. “I weighed each word,” he later remembered, “then drove it home, concentrating on the task ahead and simple facts.”21

Among the men were 177 Frenchmen belonging to the Kieffer Commando.22 Twenty-one-year-old Léon Gautier looked on as Lovat, “wearing the gilet of a gentleman farmer,” hands in his trouser pockets, began to speak.23 Slim and wiry and several inches shorter than Lovat, Gautier had served in the French navy before joining Charles de Gaulle’s Free French in July 1940. He now belonged to Troop 8, attached for D-Day to Number 4 Commando, whose mission was to seize the seaside resort of Ouistreham, at the eastern end of Sword Beach.24

At last, Lovat addressed Gautier and his fellow countrymen directly in colloquial French, and they yelled their approval.25

“You are going home,” he stressed in French. “You will be the first French soldiers to fight the [German] bastards in France itself. Each of you will have his own Boche. You’re going to show us what you can do. Tomorrow morning we’ll have them.”26

Switching to English, Lovat congratulated all of his men for being “a proper striking force, the fine cutting edge” of the British Army in the invasion. He knew they would face stiffer opposition than ever before. Described by Winston Churchill as his “steel hand from the sea,” they would land where enemy fire would be heaviest in the British sector.27

“The bigger the challenge,” Lovat told his men, “the better we play.”28

Three regular infantry battalions would land on Sword before Lovat’s first wave of commandos, helping to eliminate German defenses. This would hopefully allow the commandos to exit the beaches quickly. Lovat’s lads would then cross minefields and move inland, passing through several villages, not stopping until they had linked up with airborne troops holding key bridges some six miles from Sword.

Lovat finished with critical advice that many men would thankfully remember.

“If you wish to live to a ripe old age—keep moving tomorrow.”29

“It was truly inspiring,” remembered a British officer who listened to Lovat’s address. “There was no nonsense, no cheap appeal to patriotism. He spoke simply but he imbued each man with the spirit of the same task.”30

Lovat’s speech took all of two minutes. Then his men boarded trucks and were on their way to war. As the vehicles rolled through the countryside toward the coast, every field they passed, it seemed, had become a massive stockpile of supplies and weapons, more than two million tons of them, hopefully enough to sate an Allied army two and a half million men strong.31 “England has become one vast ordnance dump and field park,” one newsman observed. “In the whole history of the world, there never has been such a concentration of all the paraphernalia of war in so small a place.”32

It was early evening when Lovat and his commandos started to board landing craft. Some were in a jubilant mood, eager to get back to France. Among the more fearsome was a shady character who Lovat suspected had seen the inside of several French jails—tattooed on his forehead were the words PAS DE CHANCE. Tough luck.33

As for Léon Gautier, he wasn’t thinking about what he’d do to the Germans in just a few hours’ time. In a pocket of his dark green uniform he kept a portrait of a young Englishwoman called Dorothy. They’d met the previous fall while he was on guard duty. He’d heard strange noises and been surprised to find her installing a telephone in a high-security area, and he rather rudely questioned her. She was no spy, she replied defiantly, just an eighteen-year-old local girl trying to make a bit of money to support her family.

In clumsy English, Gautier apologized. They chatted, and he became smitten. Would she like to go dancing sometime? A second date followed, and then magical, precious evenings when the two jived late into the night, behind blackout curtains, oblivious to the war that would inevitably pull them apart.34 He promised he would marry her that coming October—if he lived.

It was now his turn to board his boat, Landing Ship Infantry 523, or LSI 523.

His name was called and he replied.

Gautier.

“No return ticket, please,” he added.35

It was a beautiful evening, in spite of gloomy forecasts.36 One British naval officer remembered that there was “a grotesque gala atmosphere more like a regatta than a page of history, with gay music from ships’ loud hailers and more than the usual quota of jocular farewells bandied between friends.”37

As far as Gautier could see, there were all manner of boats, hundreds and hundreds, many already heading out to sea, led by minesweepers that would clear lanes toward Overlord’s five landing beaches. Never had such a large force gathered to wage war. Gautier knew he was part of something truly colossal, the likes of which would never be seen again.38

DWIGHT EISENHOWER could do nothing more to determine the outcome of D-Day. But he could not rest his mind, even for a minute. There was no distraction in any of the things he usually turned to for relaxation, not even the cheap western novels piled beside his bed, near the overflowing ashtray, in the spartan trailer on the grounds of the stately, whitewashed Southwick House, near Portsmouth.39

The Supreme Allied Commander had to be with his troops, so he left the Georgian splendor of Southwick House, with its colonnade of paired Ionic columns, and ordered his chauffeur to drive him to Greenham Common, midway between Portsmouth and Oxford, where the 101st Airborne, the first US troops to go into action, were readying themselves for combat.

Eisenhower was driven by the raven-haired thirty-five-year-old Captain Kay Summersby, who hailed from County Cork, Ireland, and was the daughter of a “black Irish” lieutenant colonel in the Royal Munster Fusiliers.40 With her high cheekbones and slim figure, she’d found work as a model before the war. During the London Blitz she drove an ambulance with courage and skill. She knew the cost of war, having lost her American fiancé early on when he was killed while clearing a minefield in North Africa. Since being assigned to Eisenhower as his driver in May 1942, she had become utterly devoted to the plainspoken, surprisingly humble general.41 Some whispered that she was more than simply a driver, that she was, in fact, his lover. Regardless, she knew more than anyone how great the strain of preparing for D-Day had been on Eisenhower. She had seen his bloodshot eyes, his shaking hands when he lit a cigarette.

“If it goes all right,” Summersby had told him, “dozens of people will claim the credit. But if it goes wrong, you’ll be the only one to blame.”42

It was too late now to call off the whole affair. A vast fleet and an army of 200,000 invasion troops had finally been set in motion. A “great human spring,” coiled and tense for so many months, recalled Eisenhower, had finally been released.43 Would the airborne operations herald the start of a successful crusade to liberate Europe? Or would Leigh-Mallory be proved right, and the “greatest amphibious assault ever attempted” be remembered instead as Eisenhower’s tragic failure?

Eisenhower had already written what would be his final words as Supreme Allied Commander should the invasion fail. He had scribbled a few sentences on a plain sheet of paper, using a soft lead pencil because his hand was weak after dashing off so many orders and memos.44 The note now in his pocket read: “Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available. The troops, the air, and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.”45

When they arrived at Greenham Common, Kay Summersby watched as Eisenhower moved casually toward a group of paratroopers, a broad grin on his face radiating what appeared to be easy confidence. “There was no military pomp about his visit,” she remembered. “Ike shook hands with as many men as he could. He spoke a few words to every man and he looked the man in the eye as he wished him success. ‘It’s very hard really to look a soldier in the eye,’ he told me later, ‘when you fear you are sending him to his death.’”46

Corporal Bill Hayes was busy smearing a foul mixture of cooking oil and cocoa powder onto his face. Others from his company in the 101st Airborne’s 2nd Battalion did the same, knowing that those with pale faces in close combat in the hedgerow country of Normandy wouldn’t last long. They were scheduled to jump onto Drop Zone A, which Captain Lillyman and his fellow pathfinders would mark with lights and radar beacons.

Twenty-two-year-old Hayes, who had sold paint and wallpaper in a Sears store in Wisconsin before being called up, wondered if he had packed his seventy pounds of kit correctly.

Armament: three knives, a machete, .45 pistol, rifle, nine grenades, a Hawkins anti-tank mine, four blocks of TNT.

Check.

Rations: 200 cigarettes, five days’ K rations, fresh water in a canteen.

Check.

Change of underwear and socks.

Check.

Focused on his pack, Hayes heard a voice.

“Well, are you ready?”

“Yeah,” said Hayes. “I guess so.”47

Hayes looked up and was astonished to see Eisenhower standing before him. The pair exchanged a few pleasantries. Eisenhower showed no sign of the overbearing stress that caused him to chain-smoke sixty filterless cigarettes a day.

It seemed to Hayes that his supreme commander was asking him if he was scared but was being careful not to use the exact words.

“You’re damn right I’m scared,” said Hayes.48

Eisenhower wished him luck and moved on. Hayes refocused on his kit. He was among the smallest men in his unit, at five feet nine inches and 160 pounds. He had fifteen training jumps to his credit but only one at night. It didn’t take long for his mind to settle once more on what he was going to do when the Germans tried to kill him.

Eisenhower began to talk with yet another “stick,” or planeload, of paratroopers.

“Quit worrying, General,” someone called out. “We’ll take care of this thing for you.”

The time had come. All around Eisenhower, men started to put on their parachute backpacks. Each soldier was heavily burdened, some carrying almost half their body weight in extra equipment.

“Load up!”

Men began to board planes, and there was a final handshake between Eisenhower and General Maxwell Taylor, commander of the 101st Airborne.49 Then Taylor’s plane’s engines growled, and it crept down the runway, with others lined up behind, noses into the wind.

Eisenhower saluted every plane as it passed him, bound for France. “I stayed with them until the last of them were in the air,” he remembered.50 The general then walked slowly back to his jeep. Kay Summersby later recalled that her boss had tears in his eyes as she drove him away.

“Well,” said Eisenhower softly. “It’s on.”51

AROUND 9:30 P.M., boats holding the fifteen-hundred-odd elite troops of the 1st Special Service Brigade52 slipped their moorings and set sail, heading for the Channel, first crossing Stokes Bay, with its shingle beaches, near Gosport on the south coast.53 The bay was calm, the wind having died down, and on a nearby boat a New Zealand naval officer played “Heart of Oak,” the marching song of the Royal Navy, on a gramophone.54 The music carried across the water to the commandos sipping self-heating soup and chewing on biscuits, their final supper before action.

Come, cheer up, my lads, ’tis to glory we steer,

To add something more to this wonderful year;

To honor we call you, as freemen not slaves,

For who are so free as the sons of the waves?55

Lord Lovat stood on the deck of his LSI, surveying the waters around him. In the bow was a twenty-one-year-old bagpiper called Bill Millin, who held the distinction of being the only man among the Allied invasion’s 150,000 soldiers to wear a kilt—the same Cameron tartan his father, a Glasgow policeman, had worn in the trenches of World War I. Lovat had selected Millin to be his personal piper, having breezily dismissed the young man’s concerns about the army regulation that forbade pipers from being in the front lines: “Ah, but that’s the English War Office, Millin. You and I are both Scottish so that doesn’t apply.”56

Lovat had assured Millin he would be a part of the “greatest invasion in the history of warfare.” And there was no way in hell that he, Lord Lovat, the twenty-fourth chieftain of Clan Fraser, was going to wade ashore without the whining skirl of bagpipes. They were essential to men’s morale, as impactful as any weapon Millin might otherwise carry.

Now, in their LSI, steadily chugging in the direction of battle, Lovat ordered Millin to play his bagpipes.57 “It was exhilarating,” recalled one of Lovat’s men, “glorious, and heartbreaking when the crews and troops began to cheer. The cheers came faintly across the water gradually taken up by ship after ship . . . I never loved England so truly as at that moment.”58

Night was falling. Many of the commandos welcomed it, for they had operated after dark mostly with greatest success. The folds of night made them feel less tense. By contrast, countless invaders scheduled to go in with the first wave were, in the words of journalist Alan Moorehead, “oppressed by a sense of strangeness and insecurity. In the darkness the dangers of the voyage became magnified and unbearable, and the rising sea alone seemed sufficient terror, without the unthinkable climax of the assault at the other end.”59

As his boat entered the English Channel, Lovat started to relax. “Immediate worries were over,” he recalled, “with time to unwind before touch-down. Now the parcel was in the post and out of my hands.” An officer had found a bottle of gin, which Lovat and others quickly passed around. Another man pulled out a paperback he had found belowdecks—Dr. Marie Stopes’s Married Love. Giddy with gin and anticipation, Lovat and other officers laughed hard at the advice for nervous young lovers, full of performance anxiety, setting out to discover the naked truth on a honeymoon. “Soft beds and hard battles have something in common after all!” Lovat would later quip. After finishing the gin, Lovat’s officers returned to their units, “hopping across lengthening shadows on the gently heaving decks.”60

Lovat went belowdecks to rest before battle. The last time he had led men into combat—“wearing corduroy slacks, a rifle hung rakishly from the crook of his arm,” as one man recalled—was on a commando raid during the Dieppe operation of August 1942. Unlike the rest of the failed assault on the Channel port, Lovat’s attack on a six-gun battery to the west of the main landing beaches had been an unqualified success. He had stubbornly demanded that the raid be done his way, despite opposition from more senior figures, and had, according to a fellow officer, “led and controlled it perfectly,”61 earning him high praise as “probably the best military brain on either side in the Second World War.”62

Lovat was a brutally efficient marauder. Winston Churchill described him to Joseph Stalin as “the mildest-mannered man that ever scuttled a ship or cut a throat,” but at Dieppe there had been nothing good-natured about his or his men’s actions. At one point, a German sniper had shot one of Lovat’s lads and then stamped on his face as he lay wounded, incensing other commandos who saw this as a gross violation of an unspoken code of honor. The German was shot down beside Lovat’s man. A commando was quickly at his mate’s side, providing morphine, while another Green Beret bayoneted the German to death. There was, remembered one man, no “gloating, no pity for an enemy who knew no code and had no compassion.”

As his men destroyed the battery’s guns, Lovat had gestured to others and pointed to buildings nearby.

“Set them on fire,” he ordered. “Burn the lot.”

One of Lovat’s men, a junior officer, remembered that “these were not the words of a commanding officer in the British Army. They were the order of a Highland Chief bent on the total destruction of the enemy.”63

Lovat’s raid went like clockwork. “Every one of the gun crews finished with the bayonet,” Lovat nonchalantly notified his most senior commanding officer, a fellow aristocrat called Lord Mountbatten.64 But a thousand patriotic Canadians, who had been so eager to show what Canada could do in the war, lay dead. To justify this unforgivable loss, it would be argued that critical lessons were learnt from the raid, ones that would prove invaluable on D-Day: Do not make a direct attack on a heavily defended port. Ensure that supporting tanks can actually move across landing beaches—the large, round stones at Dieppe had stopped many in their tracks. Make certain that naval and air support is close and carefully coordinated with the first wave of invasion troops.

The Dieppe operation had been, in Lovat’s words, a “first-class blunder.”65 Returning to England after the failed attack, utterly exhausted, his uniform soiled, his pale face grimy, Lovat had tried to find a bed in London, without luck, and had fallen asleep in the bathtub of his officers’ club. He then spent a terrible night, swaddled in towels, lying on the floor of a library, shivering, jolted awake by a nightmare “where tracer bullets probed the darkness, and leaden feet pounded desperately on slopes of slippery [pebbles] that rolled back, like shifting walnut shells.” At dawn he had realized that he faced a greater anguish: having to inform the families of his eighteen dead men that they would not be coming home.66

Now, bobbing in darkness in the middle of the stormy English Channel, Lovat was returning to France for the first time since August 1942, when so much had gone so badly for the Allies. He felt confident that he had done everything possible to ensure that his part in Operation Overlord would be a success. His men were in superb fighting condition, having already left targets in smoking ruins along Hitler’s vaunted coastal defenses—the so-called Atlantic Wall. They had been guaranteed massive, unprecedented naval and air support. And there was no need to take a major port like Dieppe in the first days of this invasion; the Allies had performed a miracle of engineering and secretly built huge concrete caissons that would be pulled across the Channel and then linked to form two large Mulberry floating harbors. They would bring their own port with them.

Lovat removed his boots and lay down on a bunk. Before long, he was sound asleep. “I can snore through any form of disturbance,” he remembered, “provided I go to bed with a quiet mind.”67 Meanwhile, up on deck, listening to the wind growl and shivering in the spray of a spiteful sea, many of his lads were not nearly so nonchalant. Sword Beach had been described as a “hot potato” with a reinforced German garrison to contend with. And some of those who had barely escaped Dieppe two years before could not help but wonder if this time they would share the fate of those poor bloody Canadians, mown down in their scores before even setting foot ashore.

ABOARD THE USS SAMUEL CHASE, Captain Edward Wozenski and Lieutenant John Spalding were hunched over a rubber carpet, examining a mock-up of the Normandy beach defenses, complete with miniature houses and trees laid out in loving detail, all based on the most recent reconnaissance photos. Of most interest to Spalding was Easy Red, one of eight sectors on the five-mile-long Omaha Beach, which, in turn, was one of the two landing beaches assigned to US troops. “They’d set up that model of Omaha with little flags,” remembered one soldier. “Easy Red. Fox Green. Colleville-sur-Mer. We knew it like we knew our cocks in the dark.”68 There was just one exit—a draw leading through hundred-foot-high bluffs—from Easy Red, where Spalding would land at H-Hour, 6:32 A.M. It was code-named E-1 and was heavily defended by two German strongpoints.

Captain Wozenski was the commander of E Company of the 16th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Division—the storied “Big Red One.”69 Of the three American seaborne divisions to hit the beaches on D-Day, the Big Red One was the only unit to have seen previous combat. Some stalwarts had fought since 1942, first in North Africa and then in Sicily, and they resented being sent into the breach yet again.

Yet there was no choice in the matter—if men and especially tanks were to get off the beach, the E-1 draw had to be taken. Doing so was a formidable challenge, even for the most experienced of combat commanders. Unlike at Utah, steep green bluffs lay beyond a crescent-shaped beach that was studded with defensive obstacles. No fewer than eighty-five pre-sighted machine guns would sweep every inch of that beach from east to west. Just one MG42, capable of firing an extraordinary twelve hundred rounds per minute, could pump bullets three times faster than any American weapon across three hundred yards of waterfront. Powerful artillery had been aimed to fire along the beach, not out to sea, thereby inflicting maximum carnage among those who somehow managed to get past the mines and stakes that skirted the hard sands, more than three hundred yards wide at low tide.

Asked to lay money on Lieutenant Spalding, even the wild gamblers squatting around craps games on the top deck would have snorted derisively. He had joined E Company after its move to England to prepare for D-Day, and only recently had he been made a section leader, in charge of thirty-two men in one landing craft. He was not exactly raring to fight. According to a medical report, he had been deeply troubled in recent months, “nervous, irritable,” his fitful sleep plagued by “battle dreams.”70 Appearances were also less than convincing. A former sportswriter from Kentucky, with a strained marriage due to his absence and a young son he barely knew, Spalding, with his boyish face, thin frame, and unruly mop of thick black hair, looked much younger than his twenty-nine years. He had not been drafted but had decided to join the army in any case, kissing his wife and son good-bye almost a year before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.71

Thankfully, E Company had its share of combat veterans, and they were lucky to be commanded by Captain Edward Wozenski, a big bear of a man from Connecticut who had won the Distinguished Service Cross in Sicily. Having previously led Company G in combat, Wozenski was highly respected, regarded as the calmest officer under fire in the entire 16th Infantry Regiment. His words carried weight. From experience, he knew only too well that it didn’t matter how well planned the invasion was, how accurate the reconstruction of the beach was on the sand table—there would inevitably be great chaos and confusion. Things were bound to go wrong. The best way for those in the first wave to survive was to stay on their feet and keep going—to attack and kill the enemy.72

In the belly of the Samuel Chase, the soldiers of E Company were gathered in a large hallway, listening intently to a final briefing, their faces illuminated by the glow of red lights. The celebrated war photographer Robert Capa, having brilliantly covered the war in Europe for Life magazine, had chosen to land with the first wave, and he later recalled the pervading mood on the ship. “We were all suffering from that strange sickness known as ‘amphibia,’” he wrote. “Being amphibious troops had only one meaning for us: We would have to be unhappy in the water before we could be unhappy on the shore.”73

When the briefing concluded, many men returned to their quarters. Some stared, deep in thought, at the bunk above them. Many penned last letters. Green officers like Spalding worried, above all, about how they would perform in just a few hours’ time. They were more afraid of failing their men, of losing their nerve, than they were of the Germans. As with so many other junior officers in the first wave, Spalding had no idea what leadership in combat truly entailed. Hopefully, the predictions of minimal resistance would come true—and if not? Earlier that evening, he’d given his home address in Owensboro, Kentucky, to a fellow officer, just in case.

ON A RUNWAY at RAF Tarrant Rushton, Major John Howard chatted briefly with some of the pilots of the Halifax bombers set to tug his force of six Horsa gliders.

“I’ve got to hand it to you boys,” said one pilot. “We’ve flown on some sticky jobs in our time, but what you lot are going to do—well, that takes some guts.”

Howard did not want to dwell on the danger—not now, just before takeoff.

He looked at his watch and called out to his men—time to synchronize watches.

It was exactly 10:40 P.M., June 5, 1944.

“Now!” said Howard.

Watches were set.

Just a few weeks earlier, attempting to cut his force to 180 soldiers, Howard had watched grown men cry as they pleaded with him not to leave them behind. They didn’t want to abandon their mates or, no doubt, miss out on the honor of being the first British troops to fight on D-Day.

“Good luck!” one soldier shouted to a friend boarding another glider.

“See you over the other side!”74

Howard had just enough time to go from glider to glider, shaking each man’s hand. “I am a sentimental man at heart,” he later confessed, “for which reason I don’t think I am a good soldier. I found offering my thanks to these chaps a devil of a job. My voice just wasn’t my own.”75

Howard repeated three words over and over: Ham and jam. “Those were code words and they meant a terrible lot to us,” he recalled. “They were the success-signal code words for the capture of the bridges intact. The success-signal for the canal bridge was ‘ham,’ and for the river bridge, ‘jam.’ And it was a goodwill wish for everyone—ham and jam. I then took my seat in the number 1 glider. I could look through to the cockpit and see Staff Sergeant Jim Wallwork, the pilot, quite clearly.”76 Many of Howard’s men had loaded up with extra ammunition and grenades, knowing they would need all they could get. They’d be alone for quite some time until reinforcements arrived. A couple of extra magazines for the Bren and the Sten, a couple of extra Mills bombs in a pocket—any last-minute grabbed item might come in handy.77 They were, in fact, so weighed down with kit that they had to be helped up the ladders into the Horsa gliders. They staggered to their places. If they fell over, they had to be hauled back to their feet.

As Howard watched the last of the men in his glider sit down, he had a lump in his throat “as big as a damn football.”

A private nearby looked at a clearly emotional Howard and felt sorry for him.78 Whatever lay ahead would not be pretty. Their glider was about to be towed across the Channel and then set loose at five thousand feet. They would then crash-land at around one hundred miles per hour, aiming for a narrow landing strip in the dead of night with no protection against enemy flak. Survival depended completely on the glider’s pilot, Jim Wallwork. In training, he’d practiced by literally flying blindfolded, reaching a target with a co-pilot calling out times on a stopwatch and readings on a compass. Even so, tonight’s mission, he knew only too well, would require luck as much as skill.

There was a problem.

Howard’s Horsa was overweight. Too many men, packets of English cigarettes stuffed down their elasticized sleeves, had brought along too many phosphorus grenades and bandoliers of .303 ammo, too many Hawkins anti-tank mines. “The German is like a June bride,” they’d been told of the enemy. “He knows he is going to get it, but he doesn’t know how big it is going to be.”79 If Howard’s lads had their way, it would be very big indeed.

Howard looked at his troops, many still teenagers.

“One of you has got to drop out . . . I need one volunteer.”

No one answered his call, and so it was decided that some equipment would be jettisoned instead. Finally, the doors to the gliders were shut and the pilots of the Halifax bombers, which would tow them to Normandy, prepared to take off. Before long, some of Howard’s men began to feel euphoric. “Germany hadn’t a chance,” one remembered.80 Then someone said, “We’re off.” The towrope took the strain and Howard’s glider began to shift. Then men felt the glider leave the ground and Howard checked his watch—they were on schedule, in the air “right on the dot” at 10:56 P.M. Now he and his men “were cut off from the rest of the world,” he recalled, “except for Jim Wallwork’s ability to talk to the Halifax. Through the portholes we could see lots of other bombers, and we knew they must have been going to bomb the invasion front.”81

It was hard to discern other men’s blackened faces, and therefore their emotions, in the darkened interiors. Here and there, cigarettes glowed. Everyone was tense, and the usual banter heard in training was absent. But as the minutes passed and they headed toward the English Channel, the men seated nervously behind Jim Wallwork on hard benches began to ease up.82

A man at the back of the glider called out to Howard.

“Has the Major laid his kit yet?”83

Had Howard been sick?

On every previous flight, Howard had vomited. He had not taken the anti-sickness tablets offered before takeoff and now realized he was so pumped up on adrenaline, so tense with nerves, that he did not feel the least bit queasy.

Twenty-two-year-old Corporal Wally Parr, an aggressive and quick-witted cockney, was seated near John Howard. Parr had chalked the words LADY IRENE on the nose of the Horsa for good luck—his wife was called Irene.84 He looked at Howard, his commander, his “gaffer.” At times he’d thought the major was a “mad bastard” during their training in Exeter, where they’d practiced day and night, seizing a bridge over a canal, annoying the locals by fishing in the River Exe with powerful fragmentation grenades. “Slog! Slog! Slog!” That’s what life under Howard had become, a constant quest to be better, faster, sharper. “Got to be better than the chap next door. Always better.”85

Someone began to sing.86 Others joined in. Parr began belting out the chorus to “A-Be My Boy,” a music hall classic, popular in particular with the many cockneys on board.87

A-be, A-be, A-be my boy . . .

What are you waiting for now?

You promised to marry me one day in June.

In the cockpit, Jim Wallwork checked his gauges. They were at six thousand feet. The towline bowed gently, leading through the darkness to the lumbering hulk of the Halifax bomber ahead.

It’s never too late and it’s never too soon

All the family keep asking me, “Which day? What day?” . . .

A-be, A-be, A-be my boy,

What are you waiting for now?88

Nineteen-year-old Private Bill Gray, Number 1 Platoon’s Bren gunner, was less vocal than his mates—having gulped down too much rum-infused tea before takeoff, he now badly needed to urinate. Gray looked at his fellow cockneys singing at the tops of their voices. “If they could have got up and danced they would have,” he remembered. “The vast majority of us were Londoners and they were mostly London songs—‘Roll Out the Barrel’ and ‘I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles.’”89

Seated to the right of Major Howard was twenty-eight-year-old Lieutenant Herbert Denham “Den” Brotheridge, a talented soccer player from a region in Britain’s industrial heartland known as the Black Country. Just before takeoff, he’d made a bet with Howard as to who would be the first to put his feet on the ground in France.90 Despite their difference in rank, the leader of Number 1 Platoon, with his curly dark hair and thick Midlands accent, was a close friend of Howard’s. He had a young wife who was about to give birth, and in recent days he had at times become maudlin, reciting out loud the fateful lines from a famous Rupert Brooke poem:

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England.91

Howard himself had two young children with his wife, Joy, “a very pretty girl with pale green eyes, slender figure and light brown hair.” She’d been worried about Howard’s meager social pedigree, or rather what her snobbish mother might think, when they became engaged, in 1939—surely she was marrying beneath her station?92 Fortunately, things had worked out just grand with Howard, who only occasionally reverted to his Camden Town rhyming slang.93 Howard’s mother-in-law could now boast that her grandchildren’s father was a dashing major, a bona fide member of the officer class.

Every now and again, as his men belted out cockney classics, Howard glanced in the direction of Jim Wallwork, unrecognizable in his flying mask and goggles. Known to his rugby chums at grammar school as “Handsome Jim,” Wallwork had joined the army before the outbreak of the war, because he could, as he put it, “smell it coming” and wanted to cover himself “in glory and medals and [drink] free beer for the duration, surrounded by adoring females.”94 Unlike Howard, Wallwork, all of twenty-four years old, had since seen plenty of action. The only child of a World War I artillery sergeant, he’d already survived a major disaster during the invasion of Sicily in July 1943, in which a quarter of his fellow glider pilots had ditched in the sea and drowned.95

During training a few weeks back, Howard had shown Wallwork photos from aerial reconnaissance of poles newly placed in fields near Pegasus Bridge. Dubbed “Rommel’s asparagus,” the wooden poles were up to sixteen feet long and had been planted upright around seventy-five to a hundred feet apart. Rommel had ordered that mines and grenades be attached to the tip of every third pole, and then connected to other poles with trip wires, turning many fields in Normandy into infernal mazes, a veritable “Devil’s Garden.”96

Howard had been disheartened by the aerial shots.

The Germans were going to spoil the fun.

“That’s just what we need,” Wallwork had told Howard. “You remember that embankment where we end up by the road?”

Of course Howard remembered.

“Well,” Wallwork added, “we’ve always been worried about piling into that if we overshot the landing zone. A heavy landing and one grenade going off by accident and—woof—up goes the lot. Now these stakes are just right. They’re spaced so as to take a foot or two off each wing and pull us up just right.”97

Howard burst out laughing.

Surely Wallwork was joking?

Like the other glider pilots in Operation Deadstick, Wallwork had been “petrified” upon seeing the photos of the stakes.98 But what good would have come of showing his concern? The mission was not about to be abandoned. To Wallwork’s surprise, Howard had appeared to accept his highly optimistic assessment, no doubt because he wanted to believe it.

Now the French coast was approaching, a white line just visible, surf breaking on the Normandy beaches.

Before long, the Halifax bomber ahead would set them free. Then their lives would depend entirely on Wallwork.

Howard could see the tensed muscles on the pilot’s neck.99

Had Wallwork been right about those damned stakes?

In just a few minutes, he would find out.

AT NORTH WITHAM AIRFIELD,100 co-pilot Captain Vito Pedone, seated in the cockpit of his C-47, prepared for takeoff, waiting for the order to go.101 A veteran of twenty-five bomber raids over enemy territory, he knew tonight’s mission would be the most important he’d ever carry out, no matter how long he lived.102 He checked the gauges on the instrument panel, listening to the growl of the engines. He regarded his plane as the best weapon of World War II, a “sweet-flying, rugged, dependable ship,” the “point of the lance” for every major operation in Europe. If he survived the next few hours, he’d celebrate his twenty-third birthday in three weeks’ time, hopefully with his wife,103 an attractive and high-spirited first lieutenant flight nurse named Geraldine Curtis,104 who would also be on active duty on D-Day.105

Beside Pedone was the lead pilot, thirty-three-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Joel Crouch, the most experienced and highly regarded officer in IX Troop Carrier Command. In fact, he was considered the best in his business, having been the lead pathfinder pilot for the invasion of Sicily and then of mainland Italy a few months later.106

All that spring and early summer, he’d honed the skills of fellow pilots such as Pedone, sending them on three missions a day, rewarding some flight crews with forty-eight-hour passes if they could drop a dummy attached to a parachute within fifty yards of a target on the ground. On Crouch’s uniform was a pair of jump wings, a sign that he was not just any old pilot—he’d actually made nine jumps himself, and he expected all his fliers to leap at least once from a C-47 so they would appreciate what the men they were dropping were up against. There’d been broken bones and more than a few bruised egos, and his bosses in the Ninth Air Force had disapproved of the risks to valuable pilots, so Crouch had written up reports explaining that so many had sprained ankles because they’d jumped out of moving trucks, not C-47s at a thousand feet. He couldn’t have cared less what the top brass thought, so long as his men were prepared for the most critical pathfinder mission of World War II.

In just a few minutes, he’d begin to taxi along the runway and then take to the air, carrying eighteen paratroopers, pathfinders who would be the first Americans to drop into enemy-occupied France.107 In radio silence and bad weather, he’d lead two other planes in his flight in a V formation at low altitude. Other flights, carrying two hundred more pathfinders, would follow Crouch’s lead. Once safely on the ground, the pathfinders would set up radar and lights to guide the planes that would deliver an entire division of airborne troops—6,600 “Screaming Eagles.” If the pathfinders failed, the whole invasion would, too.

It was 9:50 P.M., and the light was fading fast as Crouch’s C-47 hurtled down the runway and then lifted into the air.108 Exactly four minutes later, the commander of the IX Troop Carrier Command Pathfinder Unit reported to ground control that he was on his way to France,109 flying southwest, making for the English Channel110 at three thousand feet.111 The former pilot for United Airlines, who before the war had mostly flown along the West Coast, from Seattle to Los Angeles, was now officially “the spearhead of the spearhead of the spearhead” of the D-Day invasion.112

Crouch then steered directly south, toward a major landmark, the Bill of Portland, a spur of land that juts into the wind-lashed English Channel.113 A private seated nervously on a bench in Crouch’s plane, tail number 23098, was after an hour growing impatient, wondering why Crouch was flying “around England for what seemed like hours.” An officer nearby gave a lame excuse: Crouch was trying to “confuse the enemy.”114

It was around 11:30 P.M. when Crouch saw the English Channel below, the cue, recalled co-pilot Pedone, to turn off the plane’s lights. They would stay dark until the pathfinders had “hit the drop zones and were headed back over England.”115 It was a sobering moment. Crouch knew that he and three-quarters of his fellow fliers could be killed or wounded over the next sixty minutes.116 That had been the prediction in planning.

The C-47 swooped toward the gray waves and leveled out in radio silence below a hundred feet, engines throbbing as it flew undetected toward France, passing above dozens of ships, flying so low it seemed to sailors below that it might actually clip the masts of their vessels. Crouch’s only guides were two Royal Navy boats, positioned at prearranged spots in the Channel, shining green lights. After passing the second boat, Crouch turned his C-47 ninety degrees to the left. The two other planes in his flight duly followed. Crouch spotted German searchlights, stabbing the stormy skies from positions on the islands of Alderney and Guernsey, the sole British territory occupied since 1940 by the Germans.

The eighteen pathfinders on his plane were soon belting out drinking songs as if they were headed to London for a wild weekend with some saucy “Piccadilly commandos,” not toward enemy territory. Certain to be among the loudest, Crouch knew from experience, was their commanding officer, the suave, fast-talking Captain Frank Lillyman, once described by a superior as an “arrogant smart-ass,” now standing with a black cigar clenched between his teeth in an open door at the rear of the shuddering plane.

Tonight, this night of nights, Lillyman’s stick would mark out Drop Zone A with seven amber lights, which would be turned on when Lillyman gave the order, some thirty minutes after they had dropped from around five hundred feet. The amber lights would be placed in a T. The tail of the T would indicate to later waves of pilots when to turn on the green jump light. Others in Lillyman’s stick carried Eureka radar sets, which would send out signals to be picked up by the aircraft bringing in the main body of the 101st Airborne.

Lillyman was in pain, having torn leg ligaments in a training jump four days prior. Not wanting to miss D-Day, he’d tried his best to hide the injury. At least he had his cigar to chew on, to help take his mind off the goddamn leg. The cigar was, in his words, a “pet superstition.”117 Uncle Sam had thoughtfully issued him twelve a week, and he’d never jumped without one stuck between his lips. Whenever he risked running low, his wife, Jane, a wavy-haired beauty back home in Skaneateles, in the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York, had sent him extras along with her almost daily letters, many of them about their three-year-old daughter, Susan.

In his previous forty-seven jumps, Lillyman had burnt himself only once, when he accidentally swallowed a glowing cigar butt. And just one time he had forgotten to chew on a stogie before leaping from a plane—he would always remember the glum look on his men’s faces as they approached a drop zone over England.

“Hey,” he had asked, “what’s the trouble with you fellas?”

“The captain hasn’t got his cigar,” a man replied.

Lillyman quickly pulled a cigar from a pocket and stuck it in his mouth for all to see. The jump went off without a hitch.

Tonight would be different. For the first time, he’d be in a proper fight. He’d finally get the chance to show that he could handle himself in combat, just like his father, Major Frank Lillyman. “Dad didn’t like it much when I went into the paratroopers,” Lillyman had recently told a reporter. “That was back in April of 1942 at Ft. Benning. He was an old horse cavalry man in the regular army.” Sadly, he had passed away in March 1943, a wizened and highly decorated warrior who’d also served time as a mercenary. “Dad was an honest to goodness soldier of fortune,” remembered Lillyman. “He served in the Argentine navy, the Brazilian cavalry and the U.S. navy and army.”118

Lillyman looked down at the white-capped waves of the English Channel. Crouch was now flying so low that cold water sprayed through the open door, soaking Lillyman’s combat jacket.

In a C-47 following Crouch’s plane, another paratrooper also stood at an open door. He had drunk too much coffee before takeoff and now unzipped his fly to urinate into the sea. Unfortunately, the back draft from the plane’s propellers blew his efforts into his blacked-up face and showered some of his comrades, who swore loudly in protest.

“You guys are gonna have a lot more to worry about than a little pee!” the paratrooper replied.

A cigarette perched between his lips, the paratrooper began to sing:

I’m smokin’ my last cig-a-rette,

Sing that cowboy song—

I ne-ver will for-get . . .

I’m smokin’ my last cig-a-rette.

No one needed reminding that they might soon be dead.

“Shut up, you bastard!” someone shouted.119

Standing at the open door of his C-47, Captain Frank Lillyman could see his men hunched over on folding seats, loaded down with equipment, waiting calmly for the green light. Just a few hours earlier, before boarding Crouch’s plane, Lillyman had waxed lyrical to a reporter about them, describing Private Frank “the Rock” Rocca as being “knee-high to a jug of cider and as hard as a keg of nails. He can hold that Tommy gun at his hip weaving like a hula dancer and splinter silhouette targets. [Private John] McFarlen—he’s a fighting son of a gun. He likes to fight for the fun of it. It is all I can do to keep him out of the guard house. Wilhelm and Williams—our scouts—can’t lose those guys. Mangoni and ‘Zamanakes the Greek’—what they can’t do with dynamite. Give those guys the credit, not me.”

The impressed reporter had noted, just before a “nerveless” Lillyman climbed up into Crouch’s plane, that the wisecracking captain’s “brow was knit in furrows as if he was worried . . . Then I noticed what it was—an obstinate wrapper on a slim cigar.”120

Again Lillyman peered into the distance.

A coastline appeared, and then the plane entered thick clouds.121

They were over enemy territory.

La Belle France.