Chapter 1

The simplified neuroscience of the mind

To understand something that is complex we often use a model. A model is a simplified version of the principles involved. One model of the mind is to consider it as three operating teams that are trying to work together. One team is you and the other two teams form a machine.

This chapter will look at how this model can be applied.

•The brain and mind, simplified

•The structure of the mind

•The neuroscience of the mind, simplified

•The Chimp model

•Appreciating the influence of the machine

•Decision-making

•How can we manage the machine?

•The mind of a developing child

The brain and mind, simplified

We can think of the brain as the centre for managing everything in our bodies. It controls many physical functions, such as our heart rate, our appetite, our hormone levels and much more. It also has control of many mental functions, such as how we think, how we behave and the emotions we experience. The mind is in charge of these mental functions, and this is the aspect that we are focusing on. Clearly the two aspects, mental and physical, do overlap, but let’s keep it simple!

Throughout this book I will simplify the structure of your mind, so that you can understand and manage it.

The structure of the mind

The most important point in this chapter is to appreciate that we have a part of our mind that thinks and acts and can run our lives without our input.

I will first describe the structure of the mind in layman’s terms and then explain the neuroscience. The mind can be seen as divided into two parts: you and a machine. You and the machine think and interpret your world independently. Sometimes you and the machine see things differently. So it helps if we understand how to work with this machine.

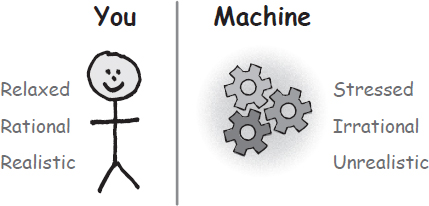

You interpret events that you experience and are in charge of your own choices. The machine has its own interpretation of the same events and has its own agenda. Very frequently, you and the machine don’t agree! For example, you might want to take life as it comes and not stress or overthink things. The machine, however, is programmed to try to make life do what it wants and typically overthinks and stresses about things.

If the machine takes over, and it can, then you can experience unwelcome behaviours and thoughts. The problem is that the machine has the power to override your own wishes and plans, if you don’t intervene. So effectively, your mind is shared between this machine and yourself.

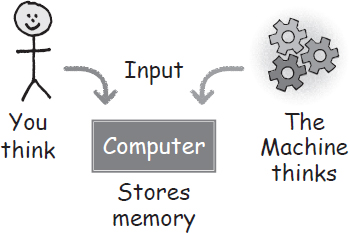

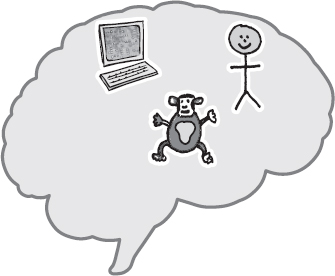

If we look at the machine more closely, we can see that it has two different parts to it. One part thinks and interprets and the other is a memory store. So we now have a thinking part of the machine, a memory part of the machine, and you. So, effectively, there are three teams operating within your mind: you and the two parts of the machine.

Both you and the thinking part of the machine have the ability to use the memory store. This memory store is very much like a computer, so from now on it will be called ‘the Computer’. When you go to act, the Computer offers advice from its stored memory.

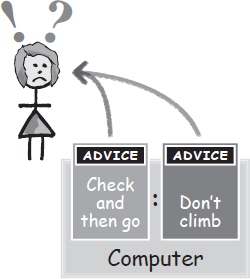

Diana and the roof tiles

Here is an example of this principle in operation. Some strong winds have dislodged a tile on Diana’s garage roof. She decides to go up and fix it. When she has climbed on to the roof, her feet slide from under her because the roof tiles are slippery. She falls from the roof and hits the ground but is okay, just very shaken. We all react differently, but this is how Diana stores this information. She puts into her Computer: ‘When I go on to some tiles again, I must check to see if they are slippery.’ Her machine, which usually overreacts, puts into the Computer: ‘Don’t ever go onto a roof again, it is dangerous and you will fall.’

When we think and interpret events we usually do this logically and rationally. Our machine cannot do this. It can only think and interpret emotionally and base its logic on these emotions. Therefore, it tends to be catastrophic in its thinking, and then works with feelings when deciding what to store in the Computer.

The problem is, that when Diana next approaches going on to the garage roof, her Computer offers conflicting advice.

The conflict that Diana experiences is between her and her machine.

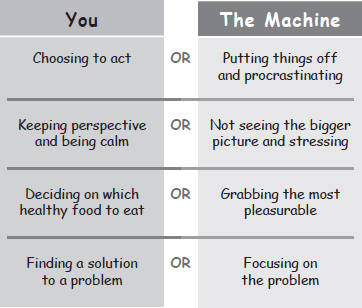

Your Machine and You in conflict

Take a moment to pause and think of examples where you and your machine have come into conflict. If you find it difficult to think of any examples, here are some suggestions that most of us have experienced as quite frustrating!

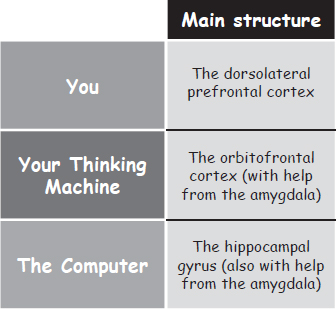

The neuroscience of the mind, simplified

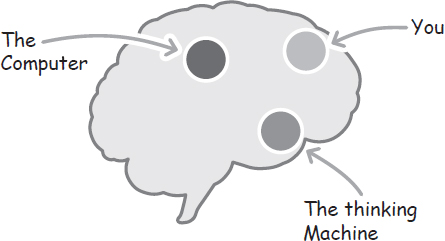

When we use scanners to watch an image of the mind in action, we see various structures or areas lighting up when they are active. Simply speaking, we can see three different teams in action: you, your thinking Machine and the Computer. Each of these teams appears to have a team leader. These leaders could be thought of as being represented by the following structures:

Simplified brain diagram to show the three team leaders

The three leaders call on many other parts of the mind for help. Some parts of the mind can multitask and some parts can be a member of more than one team. For example, the amygdala multitasks by storing emotional memory and also uses flight, fight or freeze to help us to react quickly in a perceived emergency. As the mind is complicated, I am going to keep it simple and assume we have these three teams operating together. By using this model we can make sense of complicated neuroscience. The principles applied are accurate, but simplified.[1]

The Chimp model

The Chimp model[2] is just a model! We don’t have a Chimp inside us! The model gives an easy way to access the mind and understand the neuroscience in a simplified way. The thinking part of the machine now becomes known as the ‘Chimp’.

Why am I using the terms Human, Chimp and Computer? We could call these three teams in your mind anything we want, but I am giving them the names Human, Chimp and Computer to help us to recognise how they operate.

The Human

The Human team is where you consciously think and make decisions: so this part is you.

This area interprets any information in a logical and rational way. It uses a cognitive approach for understanding. This means it uses thinking in a rational way to work out what is happening and how to proceed. It therefore learns by making sense of things. It particularly likes to ask questions. The Human also performs executive skills, such as organisation, prioritisation, ability to focus, ability to remove distractions and many other higher functions.[3] The Human has conscious awareness and is effectively you.

The Chimp

The Chimp team covers the fast-reacting systems within the mind that we have no control over but we can influence.

The Chimp thinks independently of us and can make decisions. Chimpanzees (along with many other creatures) have a similar operating area and when we both use this area, we can at times act in a similar manner! I therefore used the term ‘Chimp’ to describe those circuits in the brain that can often cause us some problems by hijacking us. These areas interpret any information from an emotional basis by using feelings and impressions.[4] [5] The Chimp therefore uses an emotional approach to understanding and learning, and works more with behaviours. It learns by trial and error and works impulsively. It doesn’t think things through but reacts to situations. This area is very fast to react and can override the Human. This part of the mind is there to help us, but sadly it doesn’t always help!

The Computer

The Computer team is a memory bank that reminds and advises the Human and Chimp teams of previous experience or knowledge. The Computer also has the ability to follow programmed thinking and behaviours.

The Computer does not interpret, so it is different to the first two teams. When the Human and the Chimp go into action and begin interpreting the world around them, they call on the Computer.[6] The Computer is like an advisor, but one who can also take over and act alone. The Computer is spread all over the brain and represents many aspects of brain functioning, including memory and automatic responses. It is programmable and will also spot patterns and make decisions for us, depending on what pattern it recognises. It therefore forms and stores learnt behaviours and beliefs. The details of the neuroscience of memory are in the notes section at the end of the book.[7] [8] [9] [10]

When we consider habits, we see them as automatic behaviours that have been programmed into the Computer. Two terms that I use a lot when working with the Chimp model are ‘Autopilots’ and ‘Gremlins’. Autopilots are helpful or constructive beliefs or behaviours that are programmed into the Computer. Gremlins are unhelpful or unconstructive beliefs or behaviours programmed into the Computer. So habits are part of these Autopilots and Gremlins. So, for those who know the Chimp model well, what we are doing is finding and replacing Gremlins with Autopilots.

For this book, I will stick to the terms ‘helpful’ or ‘unhelpful habits’, to avoid too much terminology.

Appreciating the influence of the machine

Our starting point is to appreciate and understand the strong influence of this internal machine and how it affects the way in which children and adults function.

Clearly, the machine and yourself are one person. For example, your hair colour or your eye colour belong to you, but you don’t choose them. The machine belongs to you and is your unique machine, but you haven’t chosen it. The machine can therefore drive us to do certain things, such as eat, search for security and find companionship, and it also has the ability to think for us and make decisions. As said earlier, effectively this ‘machine’ part of the brain is not within your control. Your brain machine has common features shared with everyone else, but your machine is still unique. So, for example, the eating drive is stronger in some of us than others. The need for security differs from person to person. The machine is programmed to react to your surroundings, keep you safe and ensure that you thrive. It just tends to overreact.

At different stages in your life, the machine will change its method of operating and alter its way of learning. This is a critical point for understanding children and young adults. By understanding how these changes happen, we can help young children and adults to make the most of these stages. Basically, the Human part of the brain matures very slowly, and steadily learns how to manage the Chimp and how to programme the Computer.

Important point

Our mind is constantly developing and maturing, both physically and psychologically.

When we are working with children, if we can distinguish between the child and the machine this will help us to see the child’s behaviour in a different light. Just as adults experience unwelcome hijacks and frequent unhelpful interference from the machine, so do children. We feel upset when the machine hijacks us, because we don’t agree with what it has done.

The good news is that we can learn to manage this machine and therefore influence it, and even override it. We can make our own decisions and think independently of the machine. A critical point is that we can help children to understand their own machines and we can also help to steer and nurture how a child’s machine develops and functions.

Important point

We can help a child to learn about their mind and how to manage it, and we can help to nurture the development of a child’s mind.

Decision-making

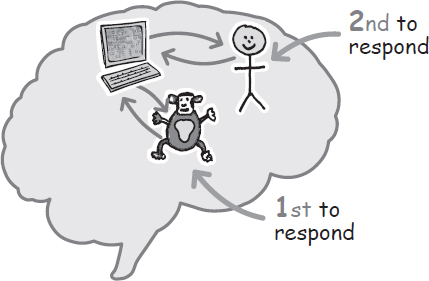

If we now take a look at the way in which we make decisions using the model, we can see that the first area to act is the Chimp. It acts by making an impulsive emotionally based decision. However, before it acts, it must get advice from the Computer to help it to make a decision.

If the Computer recognises the situation and has a plan to deal with it, then the Computer will take over. For example, let’s assume you have to make a decision on what to wear for a job interview. The Chimp makes an impulsive decision based on what it feels would be right and then calls on the Computer to give some advice. The Computer has stored memory and will feed back a lot of ideas and thoughts from past experienced[11] [12] That advice might change the first impulsive decision.

Alternatively, your Computer can just automatically put an appropriate choice of clothes on, without needing you to think.

The Human receives the information later than the Chimp and Computer. If the Chimp and Computer haven’t managed to come to a decision, then the Human will help by using a logical approach. The Human also consults the Computer and then decides on what to do. It might agree with the Chimp’s decision or it might be in conflict.

The meeting

Often in discussions in meetings, people allow their Chimps to take over and voice opinions first. These opinions are usually fuelled by emotion and evoke further emotional responses in others. After some time, things generally calm down and then the Humans begin to look at facts and use logic for the discussion, which then becomes constructive, and solutions or agreements are worked out. A lot of time and energy could be avoided if the people entering the meetings began in Human mode and represented their Chimps’ feelings in a rational and calm manner.

This scenario demonstrates the way in which we naturally operate, if we allow the mind to run its course when making decisions or discussing things. We can, of course, learn to change this pattern by developing a new habit of managing the Chimp before making decisions or discussing things.

However, just to throw things into the air again, sometimes the Chimp’s impulsive, intuitive feel is better than our logical approach! This is because sometimes we don’t have enough facts, or because our so-called facts are not accurate, whereas our intuition could accurately recognise a pattern that will predict what is going to happen. A problem arises if there is a difference in the final decision between Chimp and Human. Another potential difficulty is that the Chimp always gets information first and acts so fast that the Human might not even get a say.

Simply speaking, there are three possible ways to make a decision:

•Impulsively via the Chimp, with possible advice from the Computer

•Rapidly via the Computer, with programmed automatic responses

•Steadily and rationally via the Human, with possible advice from the Computer

Here are some examples of the Human and Chimp in conflict

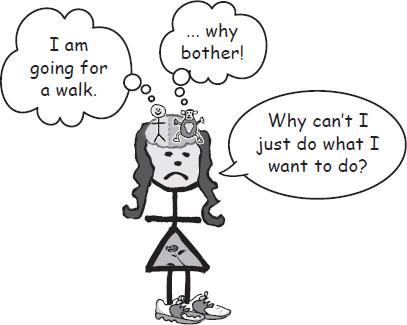

Kim and being healthy

Kim understands that being healthy is a good thing. However, even though Kim knows exactly what to do to become healthy, this just doesn’t happen. When Kim decides to go for a walk, somehow her mind interferes and forms different plans. When she decides not to become stressed about this, somehow her mind begins to worry and overthinks things. The question she asks is, ‘Why can’t I just do what I want to do and have the emotions that I want to have and carry out my plans?’

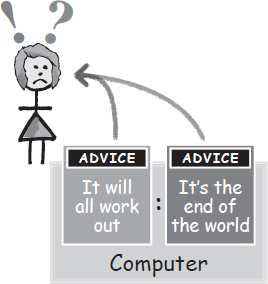

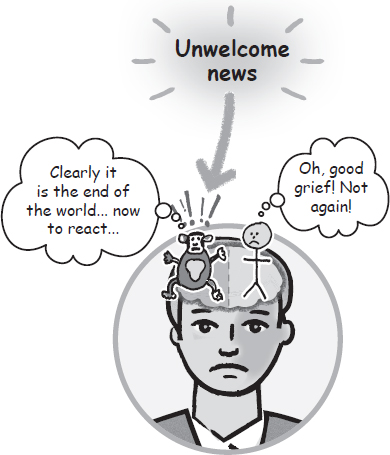

Jack and his frustration

Jack has just been given some unwelcome news that will affect his plans for the day. He gets frustrated and makes unhelpful comments, and when people try to calm him down, this gets him more agitated. He behaves in a way that he doesn’t want to, and later when he either sorts things out or realises it is not the end of the world, he calms down and regrets how he reacted.

If we scanned his head to see what was going on inside it during this time, we would see his Chimp grab more oxygen in his brain and take over against Jack’s wishes. His Chimp would not see the bigger picture, because it can’t, and it would not think of a rational way to deal with things, because it doesn’t work with rationality but rather with emotion.

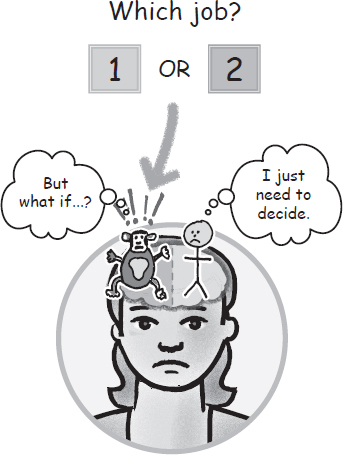

Maggie and the decision

Maggie has to make a decision between two jobs that are on offer. Her Chimp senses that she might get it ‘wrong’. It now hijacks her and begins to worry and overthink everything. Maggie’s Chimp paralyses her from making a decision. She knows this is unhelpful and that in the end she will be fine with whichever job she takes, even if it turns out not to have been the best option after all. However, because the Chimp is more powerful, Maggie is stuck.

Muhammad and the error

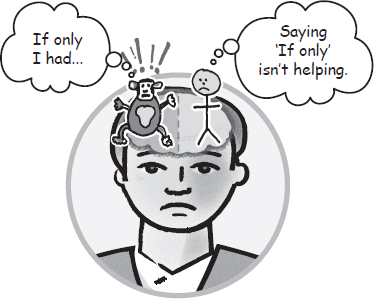

Muhammad was struggling to find an address while driving his car. His Chimp became agitated and caused a lapse in concentration, which caused him to marginally go over the speed limit and the police pulled him in. They issued him with a ticket and he returned home.

Although Muhammad accepts that his error was not deliberate and that it is not the end of the world, he finds his Chimp hijacks him for the next week with worries and agitation about his error. The Chimp constantly goes back over what he could have done and how it could have been different. Muhammad knows that this is not helpful, but he just can’t stop his Chimp from not accepting the situation and from worrying.

How can we manage the machine?

This means managing the Chimp and programming the Computer.

We have several options for managing the Chimp:

•Manage the Chimp before it hijacks you

•Programme the Computer to advise the Chimp

•Programme the Computer to take over

•Have your own Human plan

Manage the Chimp before it hijacks you

Managing the Chimp before it hijacks you means nurturing your Chimp. In other words, looking after your Chimp, emotionally and psychologically. For example, don’t allow yourself to be put into a position that could be avoided and which you know could cause your Chimp stress. So, for example, avoid trying to do two things at once: Muhammad could have stopped his car and not allowed his Chimp to become agitated and lose focus by driving and searching at the same time.

Nurturing could also mean things such as having time out, or building your self-esteem or resilience so that the Chimp feels reassured. It can also mean allowing yourself to express your feelings in a constructive way, so that the Chimp can express what it feels. So there are various ways to manage your Chimp.

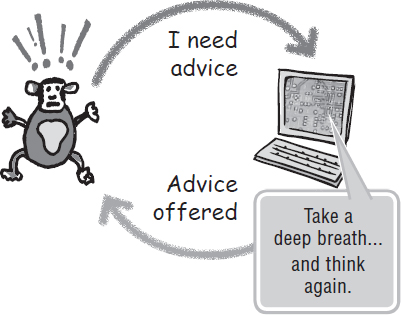

Programme the Computer to advise the Chimp

The Chimp looks to the Computer before it acts, which takes it less than a split second to do.[13] However, during this split second the Computer has an opportunity to advise and influence the Chimp greatly before it acts. For example, let’s say something has annoyed the Chimp and it is about to react. When it looks into the Computer, it finds it is programmed to tell the Chimp to take a deep breath before speaking. This advice is likely to stop the Chimp from acting impulsively and regretting what it might have said. So from the earlier example, Jack could have programmed his Computer with this advice and it might have helped him to prevent his unwelcome behaviour. Something as simple as taking a deep breath can have great rewards! This simple step can give the Human a chance to speak and bring perspective to the situation.

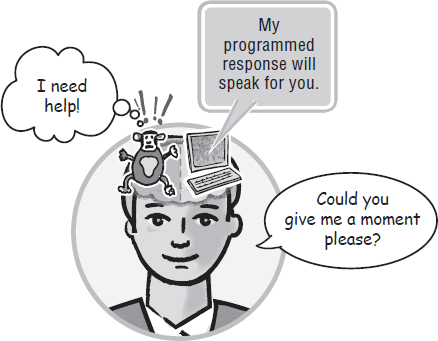

Programme the Computer to take over

The Computer can act much more quickly than the Chimp and, if it is programmed to act in a given situation, it will take over from the Chimp. For example, we can have a fixed programmed response for any situation that is upsetting us. So we might programme the Computer to say, ‘Could you give me a moment, please.’ This simple phrase can prevent us from being pressured into reacting in a way that we might later regret. We could alternatively programme the Computer to learn to distance ourselves from a stressful situation in order to regroup and gain perspective.

Have your own Human plan

In the example of Kim and the walk, she could recognise the Chimp interfering and be firm with it and learn to stick to her own plan and reject the Chimp’s ideas and thoughts. The Chimp is making an offer or suggestion and we can reject this offer. We can be firm and put our Chimp in its place!

Our Chimps are likely to be quiet and have no need to get involved in situations if they see no danger, threat or excitement. This means the Human (which is you) must now take over with decision-making. Therefore, it is helpful if you have been proactive and formed ideas and plans on how to respond to situations and programmed these into your Computer. Managing your mind effectively means being proactive. You are more likely to function effectively if you have worked out set responses to given situations that you meet frequently. For example, developing a set routine that is efficient when you arrive at work. The Computer will then take over and perform efficiently. These routines can also be programmed for our emotions, such as an emotional response to stress, for example.

How could Muhammad manage his Chimp, now that it is out?

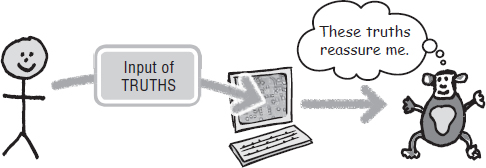

When the Chimp keeps reacting, it will look to the Computer. So here are some examples of truths that Muhammad could place into his Computer that might settle his Chimp down:

•Everyone makes mistakes and they eventually get sorted out

•There is nothing I can do now but focus on the solution, not the problem

•I can’t change the past, but I can choose my reaction to it

•Thankfully no one got hurt and I can learn from this

I am sure you can add some obvious truths of your own to the list. As long as these facts resonate with Muhammad then his Chimp will settle down.

The mind of a developing child

Now that we have an understanding of how the adult mind functions, we can look at the mind of a developing child and appreciate the differences in functioning. We will do this in the next chapter, but first an example of how some children used the model and then a summary of the chapter.

The Chimp corner

I wrote The Chimp Paradox for adults, and years later I received a scrapbook from a school. The teacher had read the book and explained to the children about their Chimps. The children had composed letters to me, telling me about their Chimps.

I was so impressed and humbled by it that I phoned the school and went to visit them. It was a great experience. The children were about eight years old. I saw that a corner of the classroom had been hived off. When I asked about this, a young boy explained that it was the ‘Chimp corner’. He said that if someone becomes a Chimp, they help them to go into the Chimp corner, and they come out when they are Human again. In the Chimp corner they can let their Chimp out. It was amazing to see in action! According to the teacher, the children had come up with the idea themselves. No judgement, no repercussions or assumptions, just acceptance and a practical way to help someone come out of a Chimp hijack. Amazing team-bonding in action!

Summary

•The mind is responsible for our mental functioning

•The mind manages our emotions, thinking and behaviours

•You share your mind with a complex machine

•The machine has two parts: the Chimp and the Computer

•The Chimp thinks and interprets, has its own agenda and can override you

•The Computer advises both the Chimp and the Human, and is programmable by either

•The Chimp always goes first when reacting to situations

•The Chimp’s reaction can be modified by advice from the Computer

•If programmed, the Computer can override the Chimp