Chapter 4

How we make sense of experiences

The older we get, the more experiences we accumulate, and the more information we can programme into our Computer. Children, however, have little experience of their world, and so need to be guided by their parents or caregivers in order to make sense of, and to navigate, the world.

•Behavioural learning

•The neuroscience of programming the Computer

•Cognitive learning

•Tidying up the Computer

•Dynamic learning

How does a child make sense of and use experiences?

There are three important ways that a child can make sense of and use experiences to learn from:

•Behavioural

•Cognitive

•Dynamic

These three approaches are not independent but merge together. I have separated them for convenience of under standing. Everybody uses all three approaches every day. Each approach has its merits and potential drawbacks.

Behavioural learning

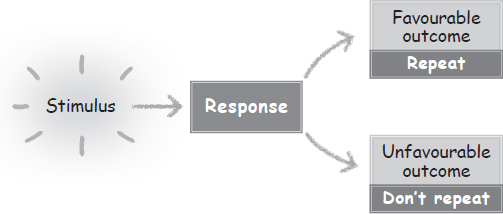

Behavioural learning involves a three-step process. We experience a stimulus, we respond to that stimulus and then we either repeat the response or try an alternative way of responding.

Here are some simplified examples:

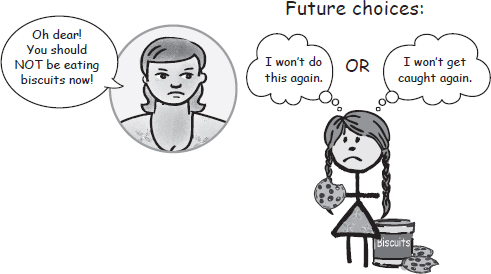

Being punished: If a child is caught stealing a biscuit from a tin and is punished, then the child is likely to either not repeat the behaviour or avoid being caught.

Evidence suggests that the most likely future response to punishment is to avoid being caught![1] Avoidance of being caught leads to possible deceit and lies. One way round this problem is to discuss with the child what they can do if they get tempted to take another biscuit. In other words give them a plan to follow. That plan could be as simple as ‘come and talk to me for some praise and some self-praise’.

Positive encouragement and praise work better than punishment, especially for challenging behaviours.[2]

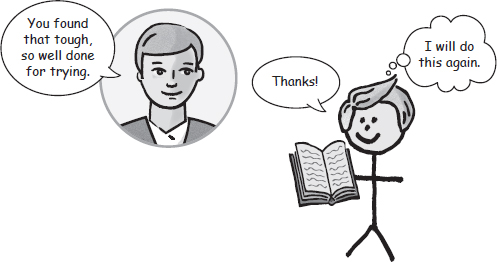

Being praised: For example, if a child, trying to read out loud a passage from a book fails to do this but then gets highly praised for trying, the child is likely to try and read again. This is because the child sees the praise as successful and therefore worth repeating.

A caution

Giving rewards to children can encourage the child to either look for an external or an internal reward. For example, if they succeed in doing something, you can reward them by giving them extra pocket money or a toy. These are external rewards that the child will look for. However, you could also reward them by helping them to feel good about themselves or teaching them how to recognise that what they have done is good in their own eyes. These rewards are internal to the child. There is evidence to show that by giving external rewards, children will look much less to themselves to be driven to do things, whereas giving positive feedback and encouraging children to make choices about their own behaviour will lead to a child being self-driven.[3] Despite research that supports this finding, there is still some evidence that giving material rewards can be helpful.[4]

A really important point

The way that you reward a child can affect the way they approach life.

Variable success

Research shows that, if we sometimes get what we want, but not every time, then we are more likely to keep on trying.[5] [6] This occasional success seems to be addictive to us. For example, occasional small wins on a lottery mean that many people will keep trying for the jackpot, even though it is unlikely to happen, because they have experienced the occasional win.

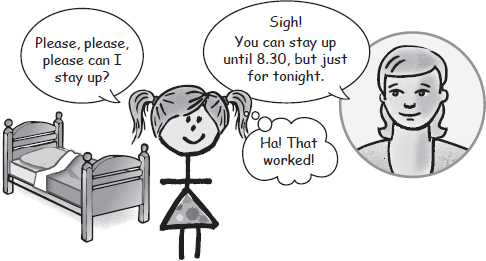

If, as adults, we are inconsistent with a child and the child gets a favourable outcome only some of the time, then this will strongly encourage the child to repeat the behaviour. This is because they will believe that if they keep on trying then they might get what they want.

Here are some examples:

Going to bed: If a parent insists bedtime is at eight o’clock but then relents occasionally, after pleas from the child, then it is likely that the child will continue to plead, believing and experiencing that the parent could change their mind.

Eating sweets before a meal: If a parent gives way and allows a child to eat sweets just before a meal, then the child is very likely to ask to eat sweets every time and to complain when they don’t get what they want.

Reflection point

Consider your own actions when interacting with a child. Are you being consistent with your own responses? Are you promoting the best response from the child?

Problem-creating and problem-solving using a behavioural approach

Developing an unhelpful behavioural pattern to a stimulus can create many problems. First, we need to recognise an unhelpful response before it can be changed. The principle is always the same: look for a stimulus and a response. If the response to the stimulus is unhelpful, try to create an alternative response that is helpful.

Here are some examples:

When something goes wrong!

The usual response when something doesn’t go according to plan is to moan, complain or become frustrated. This might be very natural, but it isn’t helpful. We can programme ourselves to learn to respond to any setback in a constructive way. So a more helpful response to a setback could be an immediate ‘this is a moment of opportunity for me’.

For example, the opportunity could be seen as:

•A challenge to learn problem-solving

•A chance to demonstrate patience

•A moment to gain perspective

With some thought, you could find a response that will resonate with your child and yourself. This then becomes a constructive and helpful habit when applied to any setback.

Tidying up a bedroom

The response here will all depend on the age of the child or adolescent! A very common problem for children and adults of all ages is tidying up after themselves. I will cover this scenario in greater detail in Chapter 16, but the main point of this example in this chapter is for you to consider if your response to the untidy bedroom will evoke the required response from the child. In other words, are you helping them to respond in a constructive way?

Typical responses from an adult to a child who has an untidy bedroom are to:

•Offer empty threats

•Complain loudly

•Appeal to the child’s sense of respect

•Repeat ‘not in my house’

•Condemn using words such as ‘lazy’

If one of these were your response, how would you expect the child to feel and respond? The child generally doesn’t want an untidy bedroom and certainly doesn’t want to feel bad about it. What the child needs is to be empowered and given some direction or guidance. Some alternative possible responses from the adult could be:

•Offer understanding and encouragement

•Make a game of tidying up, with a given short time limit

•Explain how it will make you feel if you see it tidy

•Explain how it will make them feel when it is tidy

If you prefer to go down a different route, then consequences are an option. Consequences are different to punishment, because they are avoidable and occur as a result of the child’s own actions or inactions, whereas a punishment is an imposition by an authority figure. So you could explain that an untidy room will have consequences, such as the withholding of privileges until the bedroom is tidy. (Privileges could be time on a computer, watching television or playing outside.)

The neuroscience of programming the Computer

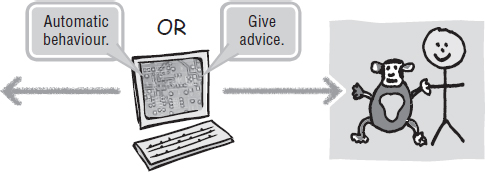

In behavioural therapy, neuroscientifically, the Computer is being programmed with an experience (stimulus) and an expected outcome (response). The Computer will then either advise the Chimp and Human with this experience, or it will automatically take over and repeat a behaviour that it thinks will get the best outcome. When we establish a behaviour, myelin, the insulating substance mentioned earlier, coats the nerves. The more we repeat a behaviour, the more myelin coats the nerves. These myelin-covered pathways become very fast-acting and turn into habits. Therefore, learnt behaviours are strongly reinforced and become hard habits to break, whether they are constructive or not.

Cognitive learning

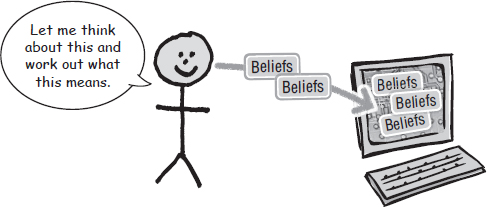

When we learn cognitively we learn by thinking, reasoning and forming beliefs. Cognitions are thoughts. The Chimp tends to work in a behavioural way and the Human tends to work in a cognitive way. Cognitive learning means that we think things through and make rational deductions on why something happens and how we can change this if we need to. A cognitive approach also means we can learn from experiences by reflecting on them. When we reflect, we form beliefs and then store these in the Computer. We have already seen that the Human areas of the mind are quite underdeveloped during childhood. However, they still function, and a child can learn to work with the Human aspect of the mind. Therefore, promoting reasoning can help develop it.

Here are some examples of how cognitions work.

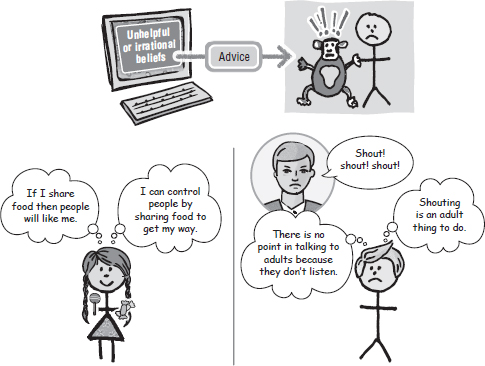

Deducing: If a child experiences an adult shouting at them for something that they didn’t do, they could form any number of beliefs and then store these in their Computer. For example, they could form beliefs such as:

•There is no point in talking to adults because they don’t listen

•Shouting is an adult thing to do

•Children are not listened to

However, they could also form more rational beliefs, such as:

•This particular adult doesn’t listen very well

•Life is not always fair

•Sometimes adults can get things wrong

Reasoning: If a child feeds a pet cat and the cat shows affection towards them, they might reason in very different ways. For example, they might reason:

•If you want affection from an animal, then you need to feed it

•If you share your food or sweets with others, then they will like you

•If I have food, then I can use this to please others

However, the child could also reason as follows:

•If I have food, I can control others

•If I have food, I can use this to bargain with

•Offering food is one way to become popular

As can be seen from the two examples, most things we do tend to be interpreted and prompt conclusions. Sometimes these conclusions will be sound and sometimes they won’t be. The problem is, that if we put unhelpful or irrational beliefs into the Computer, then this is the advice the Chimp and Human will receive from the Computer at a later time.

Tidying up the Computer

Each child will be putting beliefs into their Computer all day, every day. Many beliefs will be put in without their awareness. Therefore, when we work with children, it’s very helpful to keep discussing deductions, reasoning and beliefs with them. This way, we can help to put helpful beliefs and reasoning into the Computer, which will then act as a reference for all decisions made by the Human and the Chimp. The importance of the Computer for all of us can’t be overemphasised. It holds the power to advise on decisions in all areas of our lives.

When working with children, behavioural and cognitive methods go together as they are intrinsically linked. So, when developing behaviours, it is very helpful to explain and reason with a child in order to strengthen and back up the behaviours with rational thinking.

Important point

Discussing beliefs and reasoning is a very powerful way to help children to establish constructive habits.

Dynamic learning

Dynamic learning is not an easy concept, so I will try to simplify it. Freud[7] first postulated the idea that a lot of what happens in our heads is unconscious, and many other therapists followed with more ideas on how this might work. We can consider dynamic learning as consisting of three main themes:

•Drives

•Transfer of emotions

•Defensive thinking

Drives

Drives are forces that compel us to act in order that we can survive. So, for example, we have an eating drive. This drive gives us hunger and we then stop the drive from acting by eating. We have a drive for security and once we feel secure we relax and the drive goes away. Security is a major drive in children and is usually satisfied by a parent or equivalent.

The drive for security is important to recognise because if a child feels insecure then it is very likely to act in some way to resolve the drive. The actions it takes might not be appropriate or be misread.

Babies and very young children usually go through a period of development when they become very wary of strangers.[8] [9] They might repeat this at different ages during childhood. This is a natural response that is helpful to ensure the child stays with those it can trust. During this period the child needs reassurance and time to pass through the phase in a constructive way.

We can help by not trying to change their reaction, but by allowing the child to listen to their feelings and then adding a reassurance and offering a way to manage them. Simply explaining that when they feel concerned they can turn to you could help them.

The drive to make the child feel secure is present in order for the vulnerable child to seek support and reassurance from a parent figure. The first day at school can create a sense of panic and fear in some children. The separation anxiety of losing the parent’s protection is in-built in order for the child to seek out the parent. Seeing a distressed child, it is important to appreciate that the child is under the influence of an incredibly powerful drive. Reassurances to the child that it is natural to feel this way might help. Even very young children can understand this if we take time to explain what is happening. It might not stop the feelings the child is having, but it might help them to remove any guilt or sense that they are responsible for the feelings. There is, of course, the argument that we shouldn’t be putting children through a separation anxiety situation until they are emotionally mature enough to handle it. The time that a child reaches this stage of emotional maturity will be different for each child.

Children who therefore seem particularly anxious might be struggling to satisfy the drive for security, and reassurance rather than criticism would help.

It is always a difficult decision to make as to whether to encourage a child or to allow them to stand back when trying something they seem unsure of. I mention drives just as a reminder to consider them when trying to understand why a child might be acting in an apparently unhelpful way.

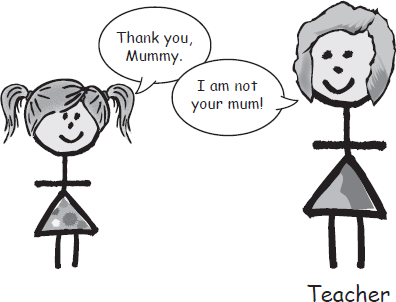

Transfer of emotions

When we experience an emotional event we can store this emotion in the Computer, and it can then be transferred into another situation. These situations can involve people or events.

For example, it is not unusual for children to transfer the feelings they have for a parent towards a teacher. The transfer of these emotions could be towards any authority figure. The transfer will then prompt the child to act in a similar way towards the authority figure as they would as if the authority figure were a parent. Transferred emotions can be appropriate or inappropriate, but they can help to explain some behaviours, beliefs or feelings that a child might exhibit. Adults can also operate in this way.

Emotions can be displaced from one situation to another, which could make it difficult to understand what is in the mind of the child. For example, if a child has not got its own way or has experienced a setback, they could displace any anger or frustration towards another sibling or to a parent. Recognising when a transfer of emotion might be taking place can help parents or caregivers not to personalise any experiences of rejection or hostility from the child.

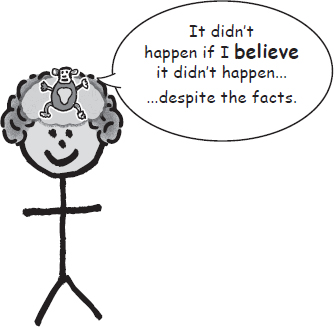

Defensive thinking

This is really about the mind trying to make up explanations that stop us from feeling emotionally stressed. We then believe these explanations. Children demonstrate a number of specific ways of thinking, in order to protect their emotions. For example, if a young child has done something wrong or has seen something they don’t like, they can then use what is called ‘magical undoing’ to protect themselves from emotional harm. This is when the child simply believes that, if they don’t believe something happened, it couldn’t have happened. For example, if the child hit their younger sibling and was challenged about this, to prevent any feelings of guilt they might magically undo the assault and claim it didn’t happen. This is different from lying, because when a child lies they know they are lying, whereas with magical undoing the child truly believes it didn’t happen.

Sadly, some adults still operate with this very narcissistic thinking and believe that whatever they think is the truth must be the truth, despite all evidence to the contrary.

Round-up of learning

We have considered three ways in which children can make sense of their experiences and then store information from this learning in their Computer for future reference. Behavioural learning is the chosen method by the Chimp. Cognitive learning is the preferred method for the Human. Dynamic learning is a mixture of input from the Chimp, the Human and the Computer. The Computer uses pattern recognition to predict outcomes.

All of us use different ways of learning and different methods. There are many styles of learning. For example, some of us prefer visual methods and some prefer practical methods. Individual children need individual approaches. Differences in temperament and learning styles mean that children respond to the same methods with different results. When it comes to helping children and adults to learn, we have to deduce what works best for them. We are all unique.

Summary

•Behavioural learning involves a stimulus, a response and reinforcement

•How an adult responds to a child’s behaviour will influence the child’s response

•Cognitive learning means learning by thinking, reasoning and forming beliefs

•Children can learn cognitively by discussion and this promotes the use of the Human part of the mind

•Dynamic learning involves managing very powerful drives, transferring emotions and defending against emotional stress