Chapter 9

Theory of mind

In order to understand how someone else feels, we need to have what is called a ‘theory of mind’. This is an important aspect of child development.

•Theory of mind

•A recognised order for learning theory of mind

•The early foundations

•Some later foundations

•What other ways are there to help children develop a theory of mind?

Theory of mind

Theory of mind simply means that we can understand what is happening in another person’s mind. For example, we can appreciate what they are feeling, what they perceive is happening, what their intentions are and predict their responses to situations. It gives us the ability to see another person’s point of view and therefore to read people. Theory of mind is one of the main emotional skills that predicts future success in all areas of our lives.[1] This increase in success stands to reason, because if you can understand another person then you are more likely to be able to communicate with them, learn from them, and form meaningful relationships with them, along with a multitude of other things.

If theory of mind is so important, it begs the question, can we help to develop this in a child? If we could do this, then it might help to give them a head start in life. Happily, the answer is that we can!

We will start by looking at how a child develops theory of mind and then look at ways of helping to awaken and develop it.

A recognised order for learning theory of mind

Children usually learn theory of mind in a recognised order. Experts differ in how they classify the way we develop theory of mind. For simplicity, here are some examples showing a general order in the way that children learn it.

•Understanding their own desires and emotions

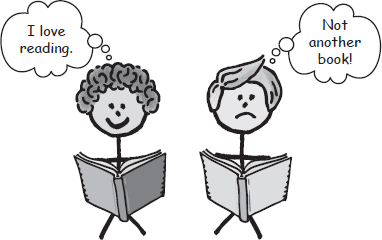

•Gaining insight into the fact that people do not always feel the same as they do

•Accepting that people act differently because they want different things

•Understanding that people can think differently when interpreting the same situation, and act differently according to what they think is happening

•Recognising that what they can see in their mind, others can’t see. Realising that they have to explain, with details, what they are seeing or recalling for others to fully understand

•Appreciating what beliefs and false beliefs are

•Recognising that people can believe things that are not true and can act on false beliefs

•Gaining insight into deception and empathy

•Accepting that people don’t always tell them their true feelings and that they can be deceived

Most children will have some level of ability and skills in all aspects of theory of mind by the age of six, but the variance is great. All of us can continue to develop these skills throughout life.

As you read the points that are being discussed, you might want to think about ways in which you can help your child to develop or strengthen the skill being learnt. If you are stuck for ideas, I have offered some suggestions towards the end of the chapter and some suggestions are interspersed as we go along.

A caution

I would like to stress the need to work from where the child has reached, in terms of their mind development.

I mentioned that the mind develops through stages, and we therefore have to work with the mind that the child has and not expect it to do something it can’t do. A child can only reach certain stages by a certain age. Of course, there will be variation in development, but to try and encourage a child to do something they can’t possibly do is obviously unhelpful.

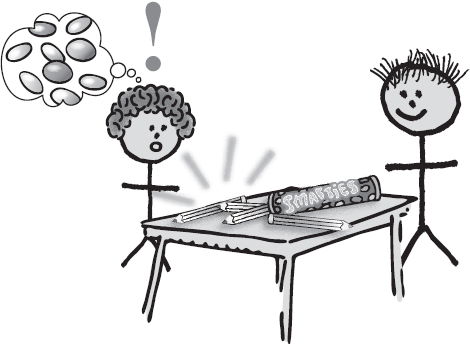

A well-known experiment might help to clarify this.[2]

Some three-year-old children were given a tube of Smarties. Before one opened the tube, the adult asked the child what they expected to find inside the tube and the child answered ‘Smarties’. However, when the child opened the tube, they found pencils inside.

The child was then asked two questions. The first question was: ‘If another child sees the tube, what do you think that this child will think is inside the tube?’ The three-year-old child usually answered, ‘They will say pencils’. The second question is: ‘When you first saw the tube, what did you think was inside it?’ The three-year-old child usually answered, ‘pencils’.

The experiment was then repeated with four-year-olds. When asked the first question, the four-year-olds answered differently. They usually said the child would expect to see ‘Smarties’. The four-year-old child’s answer to the second question was usually, ‘I was expecting to see Smarties’.

This difference in answers and insight occurred naturally over the space of one year. The three-year-olds could not adjust their thinking back to before they discovered the reality of what was in the tube, and they also couldn’t appreciate that other three-year-olds would be fooled. They effectively believed that whatever knowledge they had, others would have too.

It can be seen from this example that it would be wise to be careful when helping children to enhance their theory of mind that we don’t confuse or upset them by trying to get them to do something their mind is unable to comprehend. It is worth explaining things to them, but I am just offering a caution to consider that, even with explanation, the child might struggle to follow your reasoning.

The early foundations

Specialists in this field all agree that theory of mind begins during early childhood, but disagree as to exactly what age it occurs.[3] Rather than debate this, we can look at the fundamentals and those readers who are interested can follow up with the references.

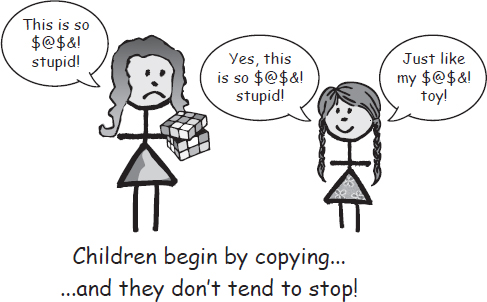

Infants typically start by copying the actions of others.

They then begin to appreciate that other people have feelings and recognise that these feelings are connected to facial expressions. The infant progresses by learning to use words to describe these feelings.

If we pause here to reflect on this, then we can see some significant possibilities to help develop these naturally occurring stages.

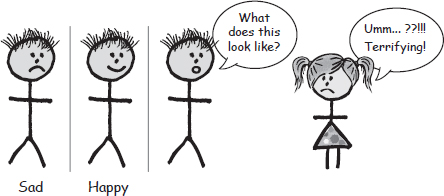

Learning about how people feel through facial expressions

Often, adults can tell how another person feels through their facial expressions. Helping a young child identify and name them is a good first step towards developing a theory of mind.

Action point

For example, we could encourage children to copy what we do. As they copy what we do, we could encourage them to say what they think our facial expression is telling them about how we feel.

Most importantly, we can help them to verbalise what this means. Getting the child to mimic different expressions or to read your expression is always fun! Helping children to use words to describe emotions will not only give an explanation to them but will also increase their language skills. With older children we can also consider body language. Different simple body language positions can be taught by asking the child to try and demonstrate how they would act for different emotions that they are experiencing.

Different feelings

As the foundations of theory of mind develop, infants become aware that people can have different feelings to the ones that the infants themselves are experiencing. People have different likes and dislikes, and therefore people act differently.

Action point

Discussion with the child about people being different in what they like and dislike will help the child to appreciate that we are all diverse. This can easily be expanded to understanding how people feel differently when doing the same thing. For example, if the child were asked to tell you how they feel when they are doing something they really like, you could then explain that another child might not like doing this activity, so how would they feel? Getting the child to discuss these notions is very beneficial in helping them to grasp these concepts.

Different motives

At some point, the child will come to recognise that actions are linked to motives and that people act according to what they want.

Action point

Learning to guess at ‘what people might do’ in different circumstances could be made into a game. For example, guessing at what someone might do if they want a bag of sweets but haven’t got the money to pay for them. Or guessing what someone might do if they have accidently damaged a toy. Discussing how everyone might react differently and even how some people might act dishonestly, will help in understanding people. Children develop the concept of deception at about five years old. Discussing deception can lead to ideas about ethics and morals.

Actions and their emotional consequences

Alongside recognising that actions are linked to motives, the child will begin to appreciate that there are consequences not only to actions but also to emotions that are being experienced.

Action point

Discussing with the child the actions they might take and the effects these actions will have on others will help them to appreciate consequences.

By the time children have reached the age of five, many aspects of theory of mind will be present.[4] Many experts agree that it is at this age that they start to contemplate what other people are feeling and thinking.

Some later foundations

Once the child begins to appreciate differences that individuals experience in thinking, motives and emotions, they then develop more complex theory of mind skills. For example, the child learns that their own experience needs to be explained in detail if someone else is to understand what they have seen or heard.

Action point

A game can easily be made out of this by letting them watch a scenario on a video clip and then helping them to select the relevant points that would help someone else understand what they saw.

A higher skill is to appreciate that someone can believe something that isn’t true and then act on this misbelief. Many people still become confused by another adult’s behaviour because they have not appreciated that it is based on misinformation or untruths.

An even higher skill is to accept that, even confronted with the facts, some people will still not believe them. The idea that someone can’t accept the truth is very hard for most of us to manage!

As the child advances in skill levels they also come to realise that people can deceive them about their true feelings and motives, which can then lead the child to interact inappropriately.

What other ways are there to help children develop a theory of mind?

Whatever we do, children will naturally develop theory of mind. The brain will lay down pathways during this emotional skill development and some experiences are likely to help the child to develop these pathways.[5]

Here are some further ideas and suggestions for aiding the development of a child, starting with the basic levels of learning and then moving into more difficult learning concepts for older children. If any of these suggestions seem relevant to you, then enjoy them! If not, try to invent other ways you feel could help a child.

Expression and words

Helping a very young child to be able to understand and express their own emotions with appropriate words is a starting point. The use of different words such as ‘annoyed’, ‘frustrated’ or ‘disappointed’ to explain more clearly how they feel will help them to understand themselves better. Try to offer scenarios that clearly would lead most people to a predictable emotion.

Some easy examples:

•A party that they were looking forward to being cancelled – disappointed

•Spilling a drink over a favourite book – upset

•Not being able to do something that they usually can do, like tie a shoelace – frustrated

•Finishing a hard job like tidying up – satisfied

•Receiving an unexpected present – surprised and pleased

•Doing a very good job – proud

•Being puzzled and wanting to know more – intrigued

Expanding on the child’s vocabulary can help them to better communicate with others. For example, if they can learn to distinguish the differences between love and like, angry and frustrated, and concerned and anxious, they can then communicate more effectively.

Role-modelling

Children naturally mimic adults or other children. By encouraging and directing this in a role-play, the child can establish constructive habits.

For example, very young children will happily mimic you as you tidy up, if you give them encouragement. This can help to form a helpful habit of being tidy. It could be fun for the child if you first agree to make a mess, with the intent of tidying up.

Older children could be asked about role-playing someone they respect or admire, and discussing what it is they admire about them and how this could be demonstrated in the role-play.

In both cases, role-modelling can be extended to discuss what the role model is thinking and why they are thinking this, enhancing theory of mind. This will help to enforce the formation of the constructive habit.

Talking about someone else’s feelings

For an older child, we can extend the idea of understanding someone else’s behaviour. For example, you could ask the child to imagine being a bus driver and ask them to be careful to watch for anyone who might suddenly walk out into the road. It’s a short step to discuss that we need to be careful because other people might not always be thinking. You could also ask them to tell you how the bus driver is feeling if the roads are very busy or he is stuck in a traffic jam and is running late.

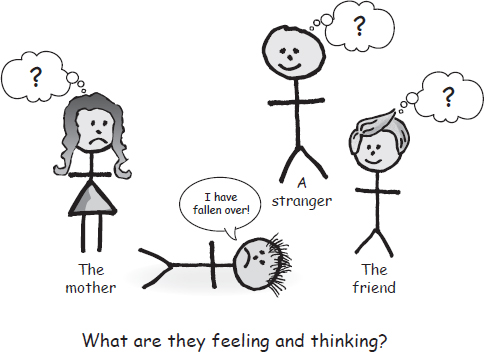

Children could be encouraged to make up or write scenarios based on feelings, and also to offer solutions on how to turn negative or unhelpful feelings into positive ones. Discussion about how to respond to other people when they are experiencing or demonstrating different emotions can also be helpful.

One way to help a child to think about other people’s feelings is to ask them to draw a picture of a scenario and then fill in thought bubbles.

Explanations help with understanding

A big step forward is when the child appreciates that, if we explain things and offer reasons for our actions, the actions are more likely to be accepted. For example, if they took a toy from a younger sibling just before the sibling went downstairs, the sibling is likely to protest. However, if the child explained to the sibling that they are helping the sibling because it could be dangerous for them to carry the toy downstairs and they will give the toy back at the bottom of the stairs, the action is more likely to be accepted.

A multitude of possibilities

There are numerous possible topics for helping to develop theory of mind in children of all ages. They are fundamentally based on thinking, discussion and reflection. Here are more topics that you could consider:

•People act differently depending on what they think is happening

•Actions and emotions that are expressed have consequences for the person and others around them

•Someone might act on a false belief

•Sometimes people will not accept the facts

•People can mislead or deceive you

•Understanding why people are sometimes surprised

Summary

•Theory of mind is the ability to understand what is happening in someone else’s mind

•Having the ability to operate with a theory of mind improves all aspects of our lives

•There are many ways in which we can help children to develop theory of mind