Chapter 13

Habit 7 – trying new things

Trying new things can enrich a child and improve their physical and psychological health. It is always worth considering what your real aim is when helping your child to try new things, and what you measure as success.

•Why do you want your child to try new things?

•Thoughts on independence

•Potential barriers for the child when trying new activities

Why do you want your child to try new things?

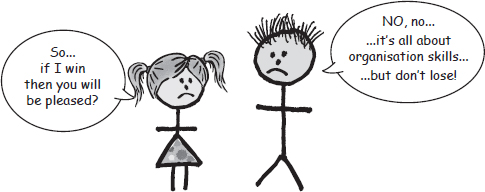

That might seem an odd question, but it’s worth answering. Trying new things has self-evident benefits, but often the real reason for encouraging children to try new things can become lost in the drive to help them to accomplish something. For example, a parent might want their child to build self-confidence. To do this, they decide to help the child to read out loud. However, they then get side-tracked into making sure that the child can read aloud and forget that the real reason for doing this is to help build self-confidence. If the child doesn’t manage to read aloud very well, then they might end up with less self-confidence. One way around this is to let the child know that as long as they have a go at reading out loud, then you see this as success. Reading aloud then becomes a very welcome bonus but being applauded for trying builds the self-confidence.

Too often in sport, we see parents who encourage their child to participate in order to learn such things as how to work in a team, organise their time or relate to others. These aims are then forgotten and winning or achieving becomes the new goal.

Even trying new food can become a battle. Parents have said to me that they want their child to be healthy by eating the right things. The battle that ensues often creates immense stress in the child, and also in the parent. Psychological health then takes second place to winning a battle about food. I accept that it is important to eat well, so the example that follows looks at how we might do this.

Peter and the new food

Peter has reached the age of eight and his diet has slowly narrowed and become unacceptable to his father. His father decides to try and get Peter to eat some vegetables. Let battle commence!

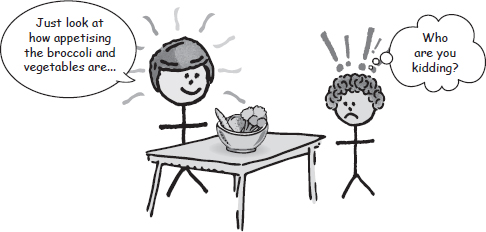

Peter’s father places the vegetables in front of Peter and encourages his son to see if he likes them. Now let’s get real here: not many people would put sprouts, cabbage, broccoli or carrots in front of burgers, chocolate, doughnuts or chips. So the chance of success is probably low.

What could the father do to increase the chance of success? Please note that I said increase the chance, not get Peter to be an avid fan of sprouts.

If you ask yourself why some adults have a balanced diet and why they want their children to follow them, then the answers could give the clues to aid success. Some key knowledge that influences adults could include:

•We understand that balanced diets are good for us

•We focus on particular foods because we know exactly what they offer for health. For example, onions aid a healthy skin and spinach has a lot of iron in it

•We accept that eating certain foods is an acquired taste

•We recognise the consequences of not eating some roughage

•We recognise the need for vitamins

In other words, our choice of food is based on sound reasoning and not just immediate gratification. Our Chimp eats impulsively and for pleasure, whereas our Human eats by considering the consequences of what we eat.

If a child understands and believes the advantages of eating a varied diet, they are much more likely to try new foods. Therefore, it might help if children find out for themselves what they would gain from trying new foods and establish these beliefs in their Computer. This will then advise the Chimp. Well at least that’s the theory!

Here are some practical ideas on how you might improve the chances of new foods being tried:

•Encouraging the child to discover some facts around certain foods. For example, spinach is loaded with iron that helps form red blood cells, which carry oxygen to muscles to give us more energy and strength. This can appeal to some children to try spinach, as they will then relate spinach to strength

•Explain to the child that foods are for healthy growth. For example: helping them to grow taller and fitter, developing their brain for thinking and strength for playing sports

•Growing their own food, such as vegetables, and then sharing these with a parent can break the taboo around trying vegetables, especially if the child helps to prepare the vegetables for eating

•It can be helpful to a child if we explain that when trying new foods it can take some time before we come to appreciate the taste or texture. The child can then understand that instant pleasure from a mouthful of vegetables is unlikely to happen!

•Mixing new foods with favourite foods can also work!

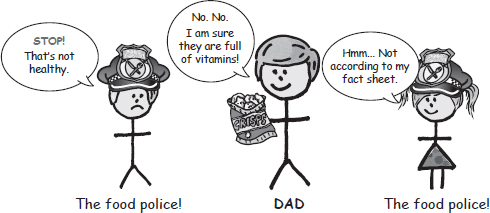

•You could ask the child to become the ‘food police’

The food police officers

One family were struggling to get their three children to eat almost any healthy food put before them. I asked the parents to try a game whereby the children became the ‘food police officers’. Their role was to take over the responsibility for the health of the family by ensuring that everyone ate a varied and healthy diet.

Sometimes, when children or young adults are given a responsibility for something, they become ardent devotees to the cause. These children took this very seriously and even had police caps bought for them. They loved monitoring to see that everyone ate well, including the children. Ironically, it was the father who wanted some relief from the stringency!

Important point

To help children to take something seriously, offer to give them responsibility for doing it.

Thoughts on independence

Trying new things and testing children’s limits can help children to develop confidence, independence and autonomy, provided some simple guidelines are followed. Research often states what might be considered as obvious, but the obvious is not always put into practice! Encouraging children to try new things can be helpful, provided the carer is not over protective or disapproving of independence. Young children who experience disapproval of any form of independence can become inhibited and see independence as wrong.[1] The difficulty is that independence can be learnt in two ways: socially acceptable and socially unacceptable. Socially acceptable ways of learning independence mean that the way in which they are learning is constructive to the child and also to those around them. Socially unacceptable ways of learning independence mean that the child might be learning, but it is causing distress or harm to those nearby.

For example, suppose a child is trying to learn how a toy works. Their older sister, who knows how it works, is watching. If the child allows the sister to watch and give them occasional guidance, then the child is learning to be independent and not reliant on the sister. All is well. However, if the child refuses to let the sister watch or becomes hostile or aggressive if she tries to offer guidance, then their interaction becomes unacceptable. Constructive independent learning is achieved by being respectful to those nearby.

Learning how independence can be seen as socially acceptable will help the child to develop their own initiative. However, if the child does not appreciate how to develop independence in a socially acceptable way then conflict or guilt is likely to arise.[2]

It would be helpful to explain these points to a young child so that they understand how to see and develop independence in a psychologically constructive way.

Important point

Encourage independence in a socially acceptable way.

It is not always easy for the adult to avoid directly criticising a child, especially if the child is acting in an unhelpful way. Sometimes letting the child know what would be helpful can turn this around. For example, the adult could explain that when we are working independently, we ought to consider the effects on others close by. It might help to suggest that accepting some guidance is good and this builds friendships. If the child wants to try something for themselves, then teaching them to ask politely, rather than impulsively taking over, can help immensely.

These points are always worth discussing with the child before the child has begun to try something new. It is much harder to manage a conflict situation than it is to prevent it from occurring in the first place.

Potential barriers for the child when trying new activities

Trying new activities can be stressful and testing to many children. For the rest of this chapter we will consider some potential barriers and ways to avoid them. These barriers can be very important to address, as many of the following unhelpful habits and beliefs that originate in childhood can be carried into adulthood.

We will consider:

•Low confidence and fear of failure

•Low self-esteem

•Perfectionism

•Excessive worrying

Low confidence and fear of failure

When children are asked to try out an unfamiliar activity that involves potential failure, many refuse to engage because of the fear of failure. A fear of not being able to do or achieve something is usually based on worries about possible comments and opinions of others.

Imagine for the moment that you live on a desert island all alone. Do you think that you would fear failure in anything that didn’t have dire consequences? If no one was about to know the result or the outcome, would you be afraid to try?

I have had the privilege of working at medical school, teaching future doctors. They take many exams and each year I would see, as a regular problem, some very stressed students with a fear of failure. Whenever I have asked the students to imagine living on a desert island or even just to imagine that no one else saw the result of the exam, even if they had multiple attempts before passing it, how would they feel? The answer is nearly always that they wouldn’t be bothered then about the result. In other words, they are basing their fear on what others think.

Some students would say that their fear of failure was based on the consequences of failing, such as not becoming a doctor. I can appreciate this. However, this fear is not of the consequences but rather of the fear of not being able to cope with the consequences, which is a very different thing. As adults there is very little that we cannot deal with. Our Chimp brain is fooling us into believing that any failure means that life can’t go on. We can’t recover from a failure – everyone has seen it and now has a low opinion of us.

As adults, we can challenge all of this. A child cannot challenge these beliefs. This is because the child’s immature brain looks to an adult for security and approval. The adult must effectively again become the Human in the child’s head. How do we do this?

This will depend on your own beliefs and values. Only you can decide how you want to approach a child who lacks confidence or struggles with a failure. Here is a suggestion. The two aspects that the adult Human part of the mind brings to a failure or setback are:

•Perspective

•Values

Perspective means explaining to the child that this isn’t the end of the world and we can redeem most things. It also means that we can deal with a failure or something we can’t redeem.

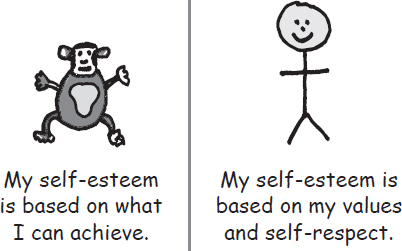

Values mean that we decide how important something is to us. Not just the success but also how important other people’s opinions of us should be. For a child, the opinion of the parent or carer is paramount. Values also include whether you think trying is more important than succeeding. The Chimp bases its value on what it has and what it can achieve. The Human bases its value on who they are and how they approach life: doing your best therefore becomes the measure of success.

Of course it’s good to applaud achievement, but is it more important than applauding effort?

Important point

Every child can gain applause for their efforts and feel good about themselves. Not every child can achieve everything they want to.

Fear of failure is often based on the false belief that, when we try something, we can always manage to achieve our best. This is obviously unrealistic. Nobody can always manage to achieve their best, even when giving their best effort. If we can programme the Computer with the truths that ‘giving your best effort is all that you can do’, and ‘achieving your best on the day is all that you can try for and hope that it happens’, then the concept of failure is given a reality check. We can’t guarantee success, but we can guarantee best effort. ‘Giving your best’ obviously means exactly that: full effort. The outcome of that effort is then something we have to accept. Of course we all want successful outcomes and ‘failures’ are disappointing. However, as adults we are big enough to manage an unsuccessful outcome and the disappointment. Children need support and approval to accept a ‘failure’. Again, as stated earlier, failure can be interpreted as a learning point.

Self-esteem

Children are trying to build self-esteem. As stated in the previous paragraph, the Chimp will try and build this on what they can achieve. There is nothing wrong with this, but there are some points to consider.

The Chimp believes that when it has achieved its goals, whatever they might be, it will be happy and have high self-esteem. The problem is that the Chimp is never satisfied for long and will soon dismiss any achievements it has made and start again from a point of low self-esteem. The reason it dismisses great achievements is that the Chimp also uses achievement to be accepted by others. It sees being accepted by others as extremely important, and therefore it cannot get it wrong. So it challenges anything it has achieved and doubts what it has achieved is good enough. This usually results in the child being very critical of themselves and what they have achieved. Any achievements are therefore doubted as not being good enough and need to be constantly improved upon in order to gain acceptance. If the child is allowed to be in Chimp mode and uses achievement for building self-esteem and proving their worth, then the consequence is usually unhelpful. It can lead to negative emotions and a sense of always having to keep proving themselves by further achievement.

The Human builds self-esteem and acceptance on values but can also enjoy achievement. The Human therefore works on self-respect. Self-respect and working with values gives the human good self-esteem. The Human can drive for achievement, while recognising that achievement is something to be proud of but not base self-esteem on. Self-esteem is based on respecting and loving the type of person that you are.

Perfectionism

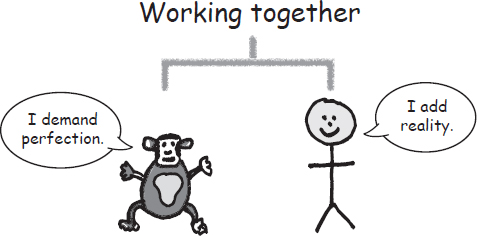

The Chimp brain and the Human brain have different outlooks and understanding of what perfection means. If they can work together, then the outcome will be optimal. I will cover this in very black-and-white terms to try and make things simple, but clearly there will be shades of grey.

The Human sees perfection as ‘doing the best I can’. This means putting maximum effort into a task and trying your best. The Human accepts that we don’t usually achieve what we are capable of, because of factors that are often outside our control. For example, running a 100-metre sprint seems very straightforward. However, on the day, no matter how much an athlete tries, there will be variable performance. This could be due to many factors, both physiological and psychological. Their body and mind are not fully under their control, and this is why we watch the 100-metre race! If an athlete got the same perfect run every time then we wouldn’t watch, because it would become predictable.

The Human therefore aims for perfection, but knows that once we have given everything, we have to accept that we don’t often get perfection.

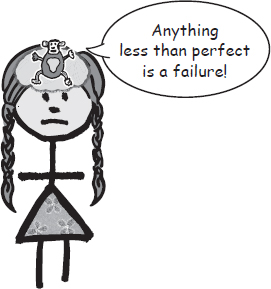

The Chimp, on the other hand, is unforgiving and demands that we achieve perfection. It cannot accept less than perfection, because this is what it wants and this part of the brain does not work with reality. If we allow ourselves to accept our Chimp’s view of the world and perfection in particular, then we can expect to feel frustrated, angry, upset or whatever other emotion that taking this approach will inevitably evoke.

The way that the two can work together is to switch over once the work is done. So by all means set off in Chimp mode, which will demand perfection and provide the enormous drive to reach perfection. The Human brain will join in with this. However, once you have finished what you are doing, it is time to switch to Human mode and accept that you couldn’t have done any more, if you gave your best. Now we might experience elation or disappointment, but we can be proud of doing our best.

An adult can accept disappointment and use this next time to improve things, if possible. The adult can do this because inside their Computer they have a simple belief that they can deal with anything that life throws at them, including disappointments. Children, on the other hand, cannot do this because they don’t usually believe that they can deal with anything in life. This is reasonable because children cannot lead an independent life. Therefore, the adult accompanying a child must again become the Human and Computer to the child.

Excessive worrying

Children are in a very vulnerable and necessarily dependent position. Therefore, it seems very natural that their Chimp will worry about most things. If the child can be encouraged to understand that their Chimp is doing a good job by worrying, then this will help to normalise the experience for them. Although it’s normal to worry, it isn’t helpful. If the child can be taught how to diffuse the worry and turn it into an action, then this will make the worry potentially very constructive.

What could the child do with worry? First accept that it is normal, even if it is not pleasant. Learning to talk about their worries is the first and most important step to settling down the Chimp. Adults use their Human and their beliefs within the Computer to settle down their Chimp. One belief that both adults and children can programme into their Computer is that, when the Chimp starts to worry, it is a message from the Chimp to act. Finding a solution to any problem rather than focusing on it will help. Getting things into perspective is another big help. Most children’s Chimps are constantly on high alert for danger, particularly when it comes to security or possible criticism. Reassurance, encouragement and praise can go a long way to settling worries.

Summary

•Try to clarify your own reasons for helping a child to try new things

•If children understand why they are trying new things they are more likely to do them

•Giving children responsibility for learning helps build autonomy

•Encourage independence in a socially acceptable way

•Removing barriers to trying new things involves the adult acting as the Human and Computer for the child

•Removing unhelpful habits during childhood prevents them from being carried into adult life