Identifying the 5 Frientimacy Gaps

Most casual relationships remain just that: casual. We don’t expect every person we meet to become our best friend, nor should we. But as we deepen some friendships by adding positivity, consistency, and vulnerability, we’ll also notice that every relationship is susceptible to one or more gaps in those three areas.

The good news is that we aren’t victims in this dance—we can address these gaps. Frientimacy gaps fall into five distinct categories, all of which can be worked through.

Most notable is the fact that identifying a gap can reveal that our discontent doesn’t automatically mean our friend is at fault, or not worthy of the relationship. Rather, identifying the gap can indicate that we need to add to our relationship, mindfully and heartfully, one of the three frientimacy requirements. As such, our role isn’t to regularly dismiss people as their judge; our role is to play friend-maker, regularly adding love—in the form of positivity, consistency, and vulnerability—to the relationships that matter to us. So let’s get started!

The Five Frientimacy Gaps

Returning to the image of the friendship being a love bucket: If our relationship is fairly new and starts to leak, we’ll want to see if we can set up boundaries to protect the budding relationship from experiencing too much stress too soon, which could doom it to failure before its benefits are fully realized. And note that the deeper the history of the relationship, the more attention we’ll want to put to fixing its leaks. I’ve seen many a relationship crumble simply because a leak was never fixed.

Low-Positivity Imbalance

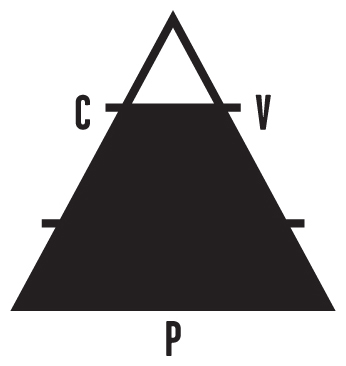

The first gap is a triangle that lacks a strong foundation of positivity. This lack could fall anywhere on a spectrum from worst to least, with stress and pain at one end and “blah” neutrality at the other end. Note that a mere lack of negativity, while not discouraging per se, nonetheless doesn’t encourage us to lean in to a relationship. For most of us to want to pursue something, we first have to feel there’s some reward in doing so—and ideally that reward will be, if not joyful, then at least pleasant.

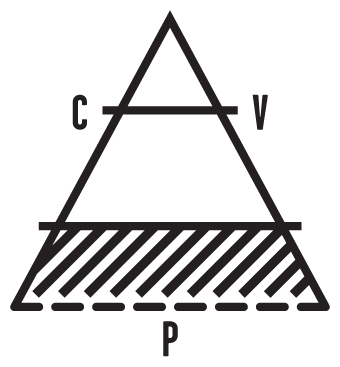

Low Positivity Gap

Since positivity is the FOUNDATION of frientimacy, we risk leaking intimacy if our positivity:negativity ratio isn’t protected.

Imagine proceeding with a friendship triangle that ranks low in positivity—to build commitment or vulnerability on a platform constructed of guilt, fear, obligation, or exhaustion continually risks the chance of collapse.

It bears repeating: healthy people aren’t looking for needy, whining, drama-filled, complaining, negative people with whom to spend time. In the process of working to make friends, our first priority is to add value, making sure we part from any get-together feeling better than we did before. Fostering hope, gratitude, peace, and love is a sweet attraction—one that encourages others to return to for more and to offer the same.

If our relationship feels like we aren’t experiencing the 5:1 ratio we discussed earlier—meaning we need at least five positive experiences in order to just balance out each negative experience—then we have two options for righting the imbalance: 1) decreasing the negativity, and/or 2) increasing the positivity.

Some negativity, such as a relationship breakup or financial loss, cannot be decreased. Life includes painful moments, so we all will experience crisis and loss. When we see our friends are struggling through rough times, we can strengthen our bonds by reaching out, offering whatever support they might need. Other kinds of negativity—such as how we interpret another’s actions, or don’t protect our boundaries—can be decreased. How? By choosing to show up differently. This could mean working to be less critical, or even just to frown less.

But even if we can’t remove all negativity, we can always add more positivity. For example, if we’re feeling our conversations with a friend dwell too much on something that’s not working in her life, we can invite her out to a comedy club and say, “Just for tonight, let’s not talk about X. Let’s give ourselves a night of laughter.” Or we could suggest an adventure—like a mountain hike—that would leave us proud, inspired, and energized. Another approach would be to collect some meaningful sharing questions (there’s a list in the Frientimacy workbook for you!) and say: “I thought it would be fun while we had dinner tonight to answer these questions together.” Including questions like “What are three things you like about yourself?” and “What do you most appreciate in your friends?” would give you both the chance to express love and affirmation. It’s just that sort of love putty that can save a friendship, allowing it the chance to fill up again with love.

Low Consistency/Low Vulnerability Imbalance

Once our base of positivity is stable and growing, we can begin to fill in the gap by incrementally increasing our commitment and our vulnerability, which inevitably will start out low. Why? Relatively new relationships are not fully cultivated—we haven’t yet developed our mutual commitment and deep sharing. So it makes sense that they would not be as meaningful as the friendships with a long history of memories and shared revealing.

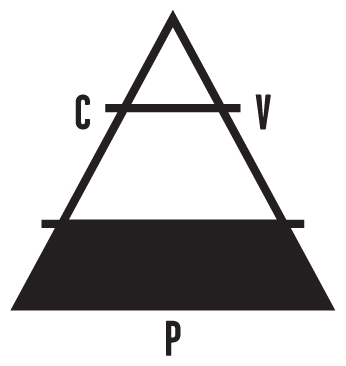

Low Consistency/Low Vulnerability Gap

Most of our relationships have a strong foundation of positivity and small, equal amounts of consistency and vulnerability.

This has nothing to do with how much we may like each other; it simply concerns the fact that friendship is based on how regularly two people repeat the positive actions that build a meaningful relationship. We cannot pinky-promise ourselves to the top of the triangle, simply willing ourselves to where we want to be. What we can do is appreciate what is there—and continually add more.

Most of our relationships will stay in this shape, with a strong foundation of positivity and small, equal amounts of consistency and vulnerability. We simply cannot enter into the highest levels of frientimacy with every person we meet. It exhausts me just thinking about it! Plus, note there is huge value in having relationships with people for reasons other than frientimacy. We feel supported when we have a wide net of casual friends (what I call “contact friends”); we feel like we belong when we have friends in the silos of our lives—at school, at work, at church, in a book club, in a support group (what I call “common friends”); and we feel loved when we have friends far and wide who we know would be there for us no matter how long it’s been since we last engaged with them (what I call “confirmed friends”).

But if all our relationships are like this, then we won’t be receiving the deeper intimacy we crave because we haven’t prioritized a few people with whom to intentionally build up our commitment and vulnerability. But once we do identify friends we’d like to build with, we can eventually close the gap by spending more time together and sharing our lives in rewarding ways.

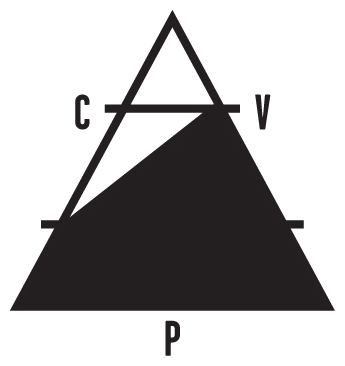

Low Consistency/High Vulnerability Gap

A common gap, one of low consistency and high vulnerability, results when we share too much, too soon, pouring more vulnerability into the relationship than the current commitment level can support. In romance (at one end of the spectrum), this gap often occurs as a one-night stand, or when one partner starts talking about marriage and babies just a few weeks into the relationship (at the other end). And while this high vulnerability might feel good in the moment—to one or even to both people—it’s not the path to safe and sustainable intimacy. Our goal isn’t just to pretend we’re close or feel bonded—it is to actually be close and bonded, which requires enough consistency and commitment to back up, or substantiate, the bonding and the sharing.

Low Consistency Gap

When we increase our vulnerability faster than we develop our consistency, we can exhaust and overwhelm a friendship.

I once worked with a woman to help her assess why she was having a hard time building intimacy. I quickly experienced firsthand that she would basically vomit her life story on people as soon as she met them. She had no problem being vulnerable—hungered for it, actually—and felt frustrated that so many others “stayed too shallow,” preferring to talk about subjects that, to her, weren’t deep enough. She thought she was helping increase their potential bond by talking about her cancer scare and her rough childhood. When potential friends didn’t take the bait, she’d get bored, believing she was too mature for all these people whom she only felt safe staying on the surface—whereas they may have been running in the opposite direction.

Many erroneously believe that the faster they spill their guts the stronger their friendship would be—but it doesn’t work that way. Vulnerability without commitment is simply a train wreck with witnesses.

Does it feel constraining sometimes to limit what we share? Of course—as it should. It’s only with my closest friends that I should be sharing all the drama, the fears, the processing, and the pity-party of my life. And as I’ve mentioned before, if I don’t have those friends in place, that’s not the fault of my newer friends—that’s simply the job of a therapist. And it bears repeating that vulnerability is far more than the information we share; it’s also the actions we risk in order to deepen the friendship.

For example, consider this text message exchange between two women who were just getting to know each other. In this case, the imbalance arose from requests that sounded more demanding than their history supported, including questions like: “What time do you get off so I can call you?” “What are you doing this weekend? I need someone to do something with.” “What kind of music do you like? Maybe we should go to a concert together.” Given that the texter tried to force a level of commitment that hadn’t yet developed between them, it’s no wonder the friendship never got off the ground.

So even though I urge you to practice deepening your vulnerability in a relationship, I also urge caution. So, for those of us anxious to rush intimacy, here are two pieces of advice, adapted from Will Smith’s matchmaking advice in the movie Hitch:

READ THE SIGNS AND LEAVE THEM WANTING MORE. We have to be observant, present, and at peace so we can tell when our energy is welcome versus when it’s too soon—the friendship equivalent of kissing a new date too early. We want to leave others excited for the next time with us, looking forward to more—rather than feeling they got more than they wanted.

INVITE, DON’T FORCE. In romantic language, Hitch advised: “The secret to a kiss is that you go 90 percent of the way—and then hold—for as long as it takes for her to come the other 10 percent.” Phrased in friendship language, we can do 90 percent of the inviting if we want to get a friendship off the ground; her 10 percent response is accepting our invitation or occasionally initiating on her own. See your energy as a “sampler” gift, by which I mean a hearty but incomplete offering, one that invites the other to complete the engagement. When we initiate, we leave space for the other to meet us.

Ultimately, we want our sharing to match the level of commitment we’ve established through our consistency. To restore balance, we might need to be mindful about not oversharing while also intentionally initiating more time together so that the consistency can grow.

Our goal is time together; it doesn’t really matter who initiates to get us there. If we’re the ones who see the need, it might as well be us.

High Consistency/Low Vulnerability Gap

The next gap is the mirror image of the last one. In this case we have a relationship that has withstood the test of some time, but not enough sharing is taking place—sharing that would reflect the trust that has been built.

In romantic terms, this could look like a marriage that has lost its soul: The couple is committed to staying, but they no longer confide in each other or feel intimate with each other. In friendship, this imbalance can present itself in numerous different scenarios, either from the requirements of the relationship not having developed in tandem—so one element grew faster than the other—or from an action that lessons one of the elements, creating a gap. Luckily, the steps to bridge this particular gap are mostly comparable, regardless of the details.

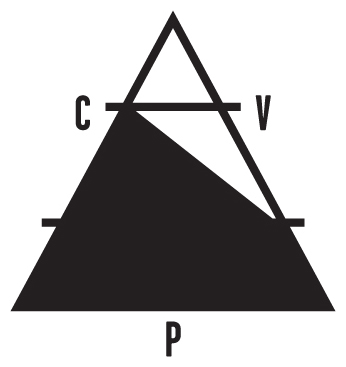

Low Vulnerability Gap

When we build up history through consistency without matching it with shared vulnerability, our lack of disclosure can limit or damage a friendship.

One scenario is in friendships where we’ve known each other for what feels like forever but our time together isn’t frequent enough for us to share our lives in meaningful ways. If we’re only chatting on the phone a few times a year, getting together for just an annual weekend, never spending time together alone, or only grabbing dinner long enough to “catch up,” then we can feel like the people we love and care about don’t really know what’s going on inside our hearts and minds. This can be a very lonely realization.

Another common scenario is when one friend finds it difficult to share with too much vulnerability, for any number of reasons. One woman told me, “I don’t even know how I feel half the time. How can I even begin to tell someone else?” Another said, “If you had been hurt as many times as I had, then you wouldn’t want to share anymore either. I can’t trust people. [That trust] always comes back and bites me.” And still another woman showed how well she knew herself by saying, “Sometimes I think I’m being honest, but I know I’m still sharing only the things that I really think get me what I want, that make me more relatable, or that somehow is done more for their sake—like, to inspire them or teach something—than it is because I’m taking my mask off and being real.”

I have been guilty of causing this gap myself, and I lost a dear, committed friend once because of it. Though I was suffering within the shambles of my first marriage at the time, I chose to not share with my friend just how dire things had gotten. And so she was shocked when we announced our separation and understandably felt betrayed by my lack of disclosure, by my seeming lack of trust in her. I had had what felt like good reasons for withholding the information—partly to protect her from carrying the burden—but the truth remains that I could have taken the risk to reveal my shame. By purposely limiting my vulnerability, I broke our frientimacy. And though this was a long time ago, I’m still haunted by this loss. And in this sort of situation, the gap can be harder to fill—because forgiveness is also called for.

There are many missteps, conscious and unconscious, that can cancel our journey to frientimacy. But whatever the scenario, the truth still stands: We will not feel known and connected in meaningful ways without eventually learning to share as much of ourselves as possible, unfiltered, with people who have proven themselves to be trustworthy.

High Consistency/High Vulnerability Gap

The last imbalance looks good on paper, as substantially more friendship has developed, with only a relatively small gap remaining. But I include this one to honor the fact that even small gaps can leave us feeling something is missing.

High Consistency/High Vulnerability Gap

Not every friendship is destined to reach the peak. It’s perfectly okay to have equal, high amounts of consistency and vulnerability; we won’t reach the top with everyone.

This imbalance might exist because a) you’re still growing the friendship, and with more time and patience it will invariably reach the pinnacle; b) the friendship has reached a plateau and needs a few intentional steps to take it into expanded territory; c) the relationship experienced a disappointment, and so some trust has been reduced; or d) this friendship hasn’t budged despite repeated efforts of growth.

How we’d address the first three scenarios gets covered in the chapters to follow. But to elaborate on the last scenario—when you feel the friendship triangle is as high as it can grow, note that not every friendship is destined to reach the peak. A relationship can only be as healthy as the individuals in it—and we’re all works in progress. Additionally, any two friends, however much they might have in common, are still very different people, with different histories and different priorities and different awareness. It isn’t realistic to believe that we can reach a peak—a “10”—with everyone. Our goal is to grow every friendship we can, as far as we choose or crave, and then to appreciate what we have with each one.

Besides, to create meaningful community in our lives, we don’t need everyone to be a “10.” Most of my closest friendships have a small gap of some kind. In one, we don’t live close to each other, so we’re limited in what we can do for each other. In another, I know she won’t consistently open up about her deepest feelings as much as I wish she did, but that doesn’t change the fact that our history and vulnerability in certain areas is deeply meaningful. In another, we can talk about some of my favorite subjects—relationships, spirituality, and personal growth—in incredibly deep and fulfilling ways, even though our vastly different lives can seem a bit disorienting at times.

In other words, my life is blessed because I have friendships with various degrees of frientimacy. And while any one friendship might have a gap, the fact that I have multiple friendships means that, collectively, my heart needs are still met. This isn’t an all-or-nothing game we’re playing. When I look at the diversely meaningful group of friends I enjoy, I can see that I don’t have an intimacy gap overall. I know with whom I can talk about my marriage, and with whom I most enjoy spiritual discussions. I know which friend to call when I want a fun adventure and which to invite for a quiet party. And I will never box any one friend into only one role, as I want to regularly try to grow friendships into new territory. I also know that if I hit a wall, I can practice contentment for all that we have and share already.

In all our friendships, we are invited to both practice contentment—working to maintain the positivity, commitment, and vulnerability we already share—while also staying open to opportunities to increase the actions that could take us deeper.

Our goal is to grow every friendship we can, as far as we choose or crave, and then to appreciate what we have with each one.

Righting Frientimacy Imbalance

The broadest answer to what limits our intimacy can be answered by asking ourselves, “What is limiting our positivity, consistency, and vulnerability?”

In short, anything that restrains you from engaging in any of the three frientimacy requirements will put a ceiling on your relationships. Therefore, if your schedule leaves you no room to connect with others—making consistency nearly impossible—then that is your answer to what confines you. Or, if you make a habit of whining and nagging and criticizing—obstructing positivity—then that would be valuable information about what keeps your relationships from growing.

To guide you in identifying what limiting behaviors might be at work in your life, I can share with you the patterns I’ve observed from talking to thousands of women about their relationships. These obstacles, as you can imagine, derive from our three requirements: friends who seem to take more than they give (positivity), friends who don’t make the time to spend with their friends (consistency), and friends who think meaningful sharing can result from simply divulging information (vulnerability). All that gets covered in the chapters to follow, so read on!

Worth Remembering

• If frientimacy is a relationship between two people that is positive, consistent, and vulnerable, then it stands that every intimacy gap reflects an imbalance of one or more of those qualities.

• Identifying the imbalance can indicate which of the three imbalances we need to develop in our relationship.

• Since positivity is the foundation of frientimacy, we risk leaking intimacy if our positivity:negativity ratio isn’t protected.

• When we increase our vulnerability faster than we develop our consistency, we can exhaust and overwhelm a friendship.

• When we build up history through consistency without matching it with shared vulnerability, our lack of disclosure can limit or damage a friendship.

• Note that not all gaps need to be fixed: We don’t need every friend to be a “10” in order to create meaningful community in our lives. Our goal is to grow every friendship we can, as far as we choose or crave, and then to appreciate what we have with each one.

Next up: the foundational element of every friendship—positivity and where it so often goes wrong.