Oh, sherry. Sometime around 2009 every one of our bartenders fell hard for this fortified wine because of how its flavors and acidity mingle so well with other cocktail ingredients. (We also loved that it’s a cheap-as-hell base ingredient—you can buy a great bottle for under $12.) Joaquín was particularly smitten with the amontillado style of sherry, which is dry but smells sweet, leaving room for the bartender to add other sweeteners to a drink. In his Flor de Jerez, Joaquín uses rum to bring out the sherry’s darker, raisiny flavors, and apricot liqueur to bring out its fruity notes.

½ OUNCE APPLETON ESTATE RESERVE RUM

1½ OUNCES LUSTAU AMONTILLADO SHERRY

¼ OUNCE ROTHMAN & WINTER APRICOT LIQUEUR

¾ OUNCE LEMON JUICE

½ OUNCE CANE SUGAR SYRUP

1 DASH ANGOSTURA BITTERS

Shake all the ingredients with ice, then strain into a coupe. No garnish.

On a Monday morning in early spring, Dave and a group of bartenders—a ragged, sleep-deprived bunch, several of whom have just left the bar a few hours ago—shuffle into Death & Co. Sausage-and-egg sandwiches, black coffee, and bottles of water are distributed. A few tattered, recipe-filled notebooks are scattered across the bar. As is custom, the bar’s newest staff member, Tyson Buhler, is selected to go first. He steps behind the bar and mixes a drink, then passes it around for his peers to taste.

TYSON The idea was to combine bourbon, port, and aquavit—three ingredients I love. I also added lemon juice and cane syrup.

PHIL When you said you were combining bourbon and aquavit, I thought, What a fucking moron. But you have some affinity here. I think it can work, but it needs a little tweaking. What’s your spec?

TYSON One and a half Eagle Rare, three-quarters tawny port, half Krogstad aquavit, three-quarters lemon, half cane, egg white.

JOAQUÍN Have you tried Linie? Its aged flavors might play better with Eagle Rare.

Tyson repeats the drink with Linie aquavit.

JILLIAN Now it tastes like a fruit and nut chocolate bar. I think it’s well balanced and tastes good, but it needs one more thing to stand out. Nutmeg?

Tyson grates some nutmeg over the drink.

BRAD I liked the first one better. It was flowery. But the cane syrup was overwhelming. Try it with simple?

JOAQUÍN It’s also got a bit of a chalky texture. A weird thing can happen with egg white drinks. If it feels chalky you actually need to add more whites to make it less so.

Tyson repeats the first version of the drink, this time with simple syrup and more egg white.

DAVE It’s an interesting idea, but there are still some kinks to work out. Let’s try it again at the next tasting.

To the uninitiated, this shorthand exchange of cocktail lingo may be indecipherable. At Death & Co we call it “the tasting,” and it’s our core creative process. Every few months we overhaul our cocktail menu, which consists of some sixty drinks. The tasting takes place over two daylong sessions, and in the process a new menu is crafted by committee, one drink at a time. Each bartender presents a series of original drinks while the rest of the staff—a mix of current and past employees—provides unfiltered feedback. Few if any cocktails are perfect on the first try. Most go through several iterations before a consensus is reached, with the head bartender getting the final say on what makes the menu. Drinks that still don’t work after a few tries are shelved for more tinkering or scrapped altogether.

We don’t take this ritual lightly. Over six years and dozens of tastings, there have been hurt feelings, broken egos, and even the occasional scuffle, but after each tasting the staff emerges united and more excited about its craft.

After forty minutes and four drinks, Tyson’s turn is up. One cocktail makes the cut, and the rest go back into development. Brad Farran is up next.

BRAD I’m calling this drink Tommy and the Ron-Dels. I wanted to do a Ron del Barrilito rum drink based on the Tommy’s margarita spec, but that was boring, so I goosed it with Galliano and tiki bitters. I used a scant half of Galliano; otherwise, that’s all you taste.

Brad shakes the drink, then strains it into a rocks glass and passes it around.

THOMAS Did you use a full half of agave? It looked like a quarter.

JOAQUÍN It looked short to me. If it’s going to get served on the rocks, it needs sugar or it will taste thin.

THOMAS You used two rums?

BRAD One and a half rum, half crema de mezcal.

JOAQUÍN You forgot to say that. I was wondering why it’s so smoky.

THOMAS You think the rum is too strong?

JOAQUÍN It’s a fruit bomb. I like rum and Galliano together, but not with crema. Maybe another rum in place of Ron del?

THOMAS What about a smokier tequila?

BRAD I like the softness and roundness of crema.

THOMAS It does need more sugar.

BRAD I’ll make another with more agave.

THOMAS And El Tesoro repo instead of crema. Sound good?

JOAQUÍN Blanco would be too green, añejo too soft. It wouldn’t stand up at all.

BRAD I’ll make another with more agave and repo.

Brad moves on to his next drink.

BRAD I call this one Cynaro de Bergerac.

PHIL What?

BRAD It’s a concept drink.

PHIL What the fuck is a concept drink?

BRAD It’s when I come up with the name first. In this case we have a great wine from Bergerac, so I wanted to come up with something made with that. Then I saw Cynar and “Cynaro de Bergerac” jumped into my head. Boom.

PHIL Let’s taste it before you induct yourself into the hall of fame.

JILLIAN It just looks like a glass of cold red wine.

PHIL It’s a concept drink, Jillian.

To everyone’s surprise, Brad’s concept drink eventually meets universal approval, while the rest are left to him for tinkering before he presents them again the following day. The next bartender, Eryn Reece, replaces Brad behind the bar and mixes her first drink.

ERYN I wanted to try a stirred Hemingway with grapefruit-infused Punt e Mes, tequila, and an absinthe rinse.

BRAD Why did you rinse with absinthe? I’d put a couple dashes in.

JOAQUÍN With the wash line on this drink, the rinse is pointless.

Thomas I like to do both.

BRAD I’m not wild about this drink. It’s confusing me.

JOAQUÍN It’s brown, muddy. Nothing’s distinctive here.

THOMAS What could you take out of it?

JOAQUÍN Maybe a little less Punt e Mes and cut the absinthe?

BRAD How dedicated are you to tequila? What if you used whiskey?

ERYN I’m not dedicated to tequila.

JOAQUÍN What about Ibis? It’s a really dry rum.

BRAD Or split Ibis and Flor de Caña 7. Flor is so subtle that it will let the Ibis speak but not dominate.

Eryn mixes a second version with rum in place of tequila.

THOMAS I think it would be tasty with whiskey.

ERYN Scotch or Japanese?

THOMAS Bourbon.

Eryn makes a third drink, this time with bourbon.

DAVE It’s still dry and too tannic. I think we have to go back to the drawing board.

THOMAS The infusion gives it a pithy bitterness. And now it’s too sweet. Take the simple out and use a teaspoon of maraschino liqueur.

BRAD What if you kill the infusion and just twist the grapefruit in before you stir?

Eryn makes a fourth iteration.

DAVE This works.

THOMAS Agreed.

BRAD The finish is interesting. I can get down with that. Can you pass it back to me so I can get down with it?

After Eryn finishes her drinks, the current head bartender, Jillian Vose, takes her turn behind the bar.

JILLIAN I made this at the end of my shift last night, so it needs some work. I did an old-fashioned variation with Willett, IPA syrup, sherry, Jerry Thomas, and orange bitters. It’s inspired by a beer and a shot.

THOMAS This smells like a boilermaker. Two, half, quarter?

JILLIAN Two, quarter, quarter.

DAVE It’s superdry, but the flavor profile is great.

Brad Hot, too.

JOAQUÍN Painfully hot—needs more water. Can you try stirring longer to dilute more?

BRAD What if you split the rye with something lower proof?

JILLIAN Like Overholt?

BRAD Like Russell’s. Then it will be sweet but not hot.

JOAQUÍN What kind of sugar did you use for the beer syrup?

JILLIAN Superfine.

JOAQUÍN I’d try cane instead, and a little more.

Jillian makes another version with two whiskeys and cane syrup.

DAVE Now it’s too sweet.

THOMAS I told you fuckers it wasn’t dry. A half ounce of sweet in a stirred drink is too much. Let’s take it back down.

Alex Day, a former Death & Co bartender and now co-owner of the bar, lives in Los Angeles, has stopped in for the tasting and is put on the spot to make a drink. He makes a drink and passes it around.

ALEX There might be sherry in my cocktail. Hold your surprise.

JILLIAN This is the first time Alex has used sherry in a drink. Be nice.

ALEX So this is grapefruit, lemon, dry sack, Perry’s Tot, simple.

JILLIAN It will be nice to mix it up by putting some lower-alcohol sherry cocktails on the menu. Most of our drinks kick your ass hard.

PHIL I feel like it’s a little abrasive. The sherry up front is nice, but the second wave ends bitter. Gin and sherry are banging heads. Let one dominate the other.

BRAD I don’t think the Tot and sherry are playing well together. What about Old Tom? Something sweeter, rounder, not as forceful.

Alex tries another version with a new gin.

PHIL It’s nice but needs a bump. A dash or two of Ango?

JILLIAN Ango is too clove-y. Needs something more interesting than that.

Alex adds tiki bitters to his next version.

PHIL Something went really wrong there. It’s amazing what a dash of bitters can do to a drink.

ALEX Ango makes everything better. I’ll use that.

It’s very easy to pour a few ounces of booze into a mixing glass or shaking tin and call it a cocktail. Sometimes that cocktail will even be delicious, but more often it will taste like what it is: a random assortment of liquids that’s more or less palatable.

The drinks that enjoy a long, sometimes immortal lifetime among the world’s canon of classic cocktails—and those that make their way onto the menu at Death & Co—are born from a combination of careful thought, applied knowledge, tireless trial and error, and, sometimes, informed dumb luck.

Within the genesis of every new drink lies an important question: are you trying to present a new idea in cocktail form, or are you creating just for the sake of creation? If the latter, it’s probably not going to be very good. It will lack the soul that all of the best drinks possess. A successful drink needs a focus, be it an inspiring ingredient, a new flavor combination, or a thematic idea, and sometimes employs a combination of these.

At Death & Co, our bartenders arrive at new cocktails using various strategies and tricks (more on these in a bit), but before any bartender—professional or otherwise—begins working on new drinks, he or she must first have a thorough understanding of some core principles. Chief among them is balance.

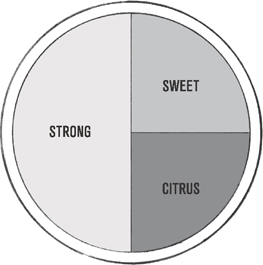

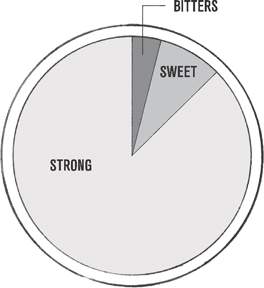

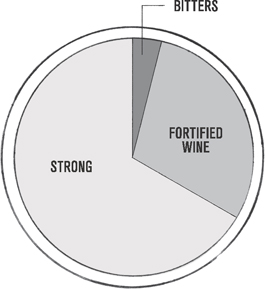

Cocktails are, above anything else, about balancing aggressive flavors and ingredients. The combination of sour, sweet, and strong is the three-legged stool of any drink. If one leg is too long or short, the drink will topple and be ill suited to its purpose. The margin of error between bad, good, and great is maddeningly fickle and sometimes amazingly thin, but a well-balanced cocktail will at least ensure a drink that’s pleasant to consume.

When considering balance, we break drinks down, rather loosely, into three families: sours, old-fashioned-style cocktails, and Manhattan- or martini-style cocktails.

With three basic elements—strong (liquor), sour (citrus), and sweet (sugar of some sort)—the basic sour formula of two parts strong to one part each sour and sweet is the foundation for almost every cocktail involving citrus, and it’s a platform on which we create countless drinks. The magic comes in the nuance, increasing one element or another by a small amount. We enjoy our sours with slightly less sweetener and a touch more sourness than some, though never to the point of being too tart. To get an idea of how these three basic elements influence a sour, let’s do an experiment.

… The Goldilocks Experiment 1: The Daiquiri, Three Ways …

The best litmus test for a bartender’s craft is a daiquiri. A simple drink (rum, fresh lime juice, and sugar), the daiquiri is the perfect vehicle for testing the ability to make a properly balanced drink, as it’s very obvious when one is made incorrectly. But reading about balance is rather dry and in no way delicious. It’s more fun to experience balance by having a drink (or three) to taste the difference between what we deem too sweet, too tart, and just right. So we recommend that you make three daiquiris using the following recipes. Be careful with your measurements, as the variations in measurements between the three versions is small, and the flavor of each drink will be significantly altered if you’re off by even the smallest amount. If after tasting all three drinks you think we’re crazy and prefer one of the other daiquiris, that’s just fine: everyone has a different palate. That’s part of what makes cocktails fun. Of course, you’ll want to use the same type of rum for all three versions. We recommend Caña Brava or Flor de Caña extra-dry white rum.

Shake all the ingredients with ice, then strain into a coupe. Garnish with the lime wedge.

Shake all the ingredients with ice, then strain into a coupe. Garnish with the lime wedge.

········

Shake all the ingredients with ice, then strain into a coupe. Garnish with the lime wedge.

Styles of cocktail that don’t contain a sour element can still suffer from imbalance. An old-fashioned is another simple recipe on the surface: booze of any kind (rye whiskey in this case), a small proportion of sugar, bitters, and citrus twists. (For our old-fashioned recipe.)

In an old-fashioned, balance manifests in a different way than in a sour. It’s all about enhancing the flavor of the base spirit in a pronounced and focused way while rounding off the edges, making it easier to consume than straight booze. Add just a bit too much sweetener and the drink tastes bland. Skip the bitters and it’s just sweet. And an old-fashioned without a twist of citrus (we prefer ours with both lemon and orange twists) lacks the bright aroma that will lighten the drink’s booziness. As for forgoing the whiskey, we can’t help you there. Have a beer or something.

Manhattans and martinis are somewhat similar to old-fashioneds, but fortified wine (usually vermouth) replaces the sweetener, typically in larger proportions. The same principles apply (enhancing the base spirit while rounding its edges), but the bitters or bittering ingredients serve a more important function in bridging the other flavors.

… The Goldilocks Experiment 2: The Manhattan, Three Ways …

Let’s get back to drinking. Achieving perfect balance in a well-made Manhattan is one of the greatest cocktail accomplishments. Beyond accurate measurement, it requires a thoughtful consideration of every single ingredient in the drink and how they fit together. At Death & Co, our standard Manhattan recipe contains Rittenhouse 100 rye matched with our House Sweet Vermouth and a couple of dashes of Angostura bitters. There’s nothing revolutionary here, but we love the balance between those three ingredients: the rye takes center stage, but the vermouth shares the spotlight, offering a round texture and extra depth of flavor. The bitters connect them harmoniously and add just a hint of spicy bite. Although it’s unquestionably a stiff drink, it’s a balanced recipe. If you were to make it any boozier, it would taste like diluted whiskey. And without bitters, it just wouldn’t make sense.

2½ OUNCES RITTENHOUSE 100 RYE

½ OUNCE HOUSE SWEET VERMOUTH

2 DASHES ANGOSTURA BITTERS

GARNISH: 1 BRANDIED CHERRY

Stir all the ingredients over ice, then strain into a coupe. Garnish with the cherry.

········

Stir all the ingredients over ice, then strain into a coupe. Garnish with the cherry.

········

2½ OUNCES RITTENHOUSE 100 RYE

¾ OUNCE HOUSE SWEET VERMOUTH

2 DASHES ANGOSTURA BITTERS

GARNISH: 1 BRANDIED CHERRY

Stir all the ingredients over ice, then strain into a coupe. Garnish with the cherry.

Balance extends into garnishes. Placing a wedge of citrus on the rim of a glass offers the drinker an opportunity to adjust the cocktail to his or her liking: with a quick squeeze, tartness levels can be increased as desired. But a garnish also imparts aroma, a valuable but often overlooked component of balance. A lime wedge, for example, has an intense fragrance, creating a greater impression of freshness and acidity, and as the first sip is taken, its aroma will mingle with the liquid and impact the overall composition of the drink. In boozy cocktails, a strategic garnish can have an even greater impact. Citrus twists have the advantage of offering the suggestion of acidity in a drink without contributing excessive flavor. A martini garnished with a lemon twist isn’t lemony, but its flavors are certainly brightened.

Throughout the more than four hundred recipes that begin, you’ll probably notice that the basic formulas outlined above reveal themselves time and time again. When making a fizz-style drink, for example, we start with a sour template but decrease the citrus a bit, serve it in a fizz glass, and top it with club soda. For a collins, a fizz is poured over ice in a taller glass. Swizzles and tiki-style drinks are centered around aggressive ingredients, but they too are fundamentally sours. And although many of our old-fashioned variations may seem very much unlike an old-fashioned, if you parse the ingredients, you’ll spot the classic formula. And almost any of our cocktails combining a strong spirit with fortified wine and bitters can be traced back to the Manhattan or martini.

Once you can identify a balanced drink—and adjust one that isn’t—creating new cocktails gets a hell of a lot easier. But before you begin throwing a half dozen (or more) ingredients into the mixing glass, consider this: in cocktails, simplicity will always reign supreme (though you won’t always get that impression when looking at our recipes). There will never be a drink that can match the elegance of a well-made gin martini. A daiquiri will refresh your mind and senses better than a day at the spa. And nothing is better before a meal than a Negroni. These are just facts, people.

Knowing this—that all of the finest drinks are profoundly delicious because of their simplicity—we approach the creation of new cocktails first as an exercise in moderation. After defining for ourselves what the focus of the cocktail will be, we begin to carefully—and intellectually—assemble its elements. We ask ourselves what will go best with a key ingredient, and more importantly, we strive to understand why certain ingredients pair well. A lot of liquor can be wasted when developing cocktails, so we try to have a solid estimation of how it will all come together before we start actually fiddling around with the ingredients.

This process is informed by a fanatical interest in ingredients and an ever-evolving awareness of how they play with one another. From this foundation, we begin trying out ideas. There are times when simplicity gets trumped by an exciting combination of many ingredients, often used in very small quantities. But there is a fine line between complexity and extravagance. As more ingredients get added to a drink, we always ask ourselves if they belong: Are they adding something to the drink, or just resulting in a complicated soup? More often than not, less is more: it’s easy to make a ten-ingredient drink taste like nothing (or worse) and incredibly difficult to turn that same number of ingredients into something greater than the sum of its parts. When you see recipes in this book with long lists of ingredients, it’s hopefully because we accomplished just that.

It’s much easier to describe and discuss the various components of a drink—which range from texture and temperature to the specific aromas and flavors present—when you have a common language to work from. Use the wheel at right to enhance your cocktail vocabulary—or simply to help you decide what you’re in the mood to drink.

The creative origins of many of the drinks we’ve created at Death & Co can be traced back to a few simple strategies.

Phil Ward coined the term Mr. Potato Head around the time he was developing Death & Co’s inaugural menu. Phil’s head is filled with hundreds, if not thousands, of specs: ratios of ingredients that are the basis of countless classic cocktails. By substituting one or more elements from an existing template with a different ingredient, like changing Mr. Potato Head’s nose—or even swapping out an eye for his nose—you can create a variation that tastes drastically different. In Phil’s words, “Every great drink is the blueprint for many other drinks.” An early example of this technique can be found in his Scotch Lady, in which he swaps the gin in the classic Pink Lady recipe for blended Scotch. He used a similar substitution in his Pete’s Word, a variation on the Last Word, a not-quite-classic drink that dates back to the 1950s.

The easiest way to get accustomed to the Mr. Potato Head technique is to start with a simple, spirituous cocktail and play around with different base spirits. Beginning, you’ll find variations on the classic Sazerac made with cognac, rum, gin, numerous styles of whiskey, and even aquavit. The Negroni is another favorite template for Mr. Potato Head variations: Like apple brandy? Try the Vanderbilt. More a fan of tequila? Make yourself a Range Life.

Keep in mind that not every substitution should be one for one. Some spirits are more alcoholic or assertive than others, and amounts of these, or the other ingredients in the cocktail, will need to be increased or decreased accordingly to restore balance.

After you’re comfortable with swapping base spirits, try substituting modifiers, then fresh juices, sweeteners, and bitters. You’ll find that certain ingredients and flavors across these categories work better together; for example, tequila loves lime, while whiskey prefers lemon. To help you get started, we created a chart of some of our favorite flavor pairings.

Another easy way to create new drinks is to transform a simple, standard (aka naked) cocktail by adding an extra layer of complexity. One of our favorite ways to do this is by infusing additional flavors into base spirits or modifiers. With this approach, you can transform the flavor profile of the drink without altering the other ingredients. A great example of this is the Chamomile Julep, in which rye infused with chamomile tea turns the boozy Derby-day favorite into something more elegant. And we love jalapeño-infused blanco tequila and use it often to add an invigorating kick to popular tequila drinks, as in the Spicy Paloma.

Flavored syrups, which are basically sweet infusions, are also fair game for enhancing naked drinks. In his Boukman Daiquiri, Alex Day swaps Cinnamon Bark Syrup for simple syrup in a daiquiri variation, making a traditionally warm-weather cocktail ready for wintertime drinking.

We also add small amounts of intensely flavored modifiers to increase the depth and complexity of otherwise simple classics. Phil’s Bitter French turns the classic French 75 into an aperitif with the addition of a small amount of Campari. The daiquiri is particularly well suited to this technique, as seen in the Jovencourt Daiquiri, in which just ¼ ounce of mezcal turns an otherwise standard daiquiri into something smoky and beguiling. Another good example is the D.W.B., a daiquiri made extra-funky with the addition of intense Batavia arrack.

To take this idea a step further, we often combine an infusion with an extra modifier, as in the Short Rib, a margarita made with jalapeño-infused tequila and a small splash of syrupy pomegranate molasses, or Thomas Waugh’s Coffee and Cigarettes, a variation on the Rob Roy made with coffee liqueur.

Using a combination of base spirits in a cocktail seems like an obvious springboard for creativity now, but when we opened Death & Co, few bartenders were doing this. Phil was the first at our bar to experiment with split bases. His Martica was his initial foray into this technique; it includes 1 ounce each of cognac and Jamaican rum as the base for a variation on the Martinez (but as you’ll see, our house Martinez uses both a split base and a split modifier). Another early example is the Wicked Kiss, in which the base for the Widow’s Kiss—a nineteenth-century drink made with calvados—is split into equal parts of rye and apple brandy.

Although very few classic cocktails feature split bases (the cognac- and rum-based Between the Sheets is one exception), the practice has a long history in tiki cocktails, in which two or more rums are often blended to achieve a more complex (and extra-boozy) foundation. One night, our in-house tiki expert, Brian Miller, decided to use the same tactic on a whiskey-based drink he was asked to make on the fly. His Conference—an old-fashioned variation made with equal parts rye, bourbon, calvados, and cognac—was a revelation to us all, and soon split bases were showing up in many of our new drinks.

When implemented poorly, multiple base spirits can turn a drink into a muddy mess, as in Long Island Iced Tea, so this method requires more attention than just simple division. Even if two spirits taste fine together, they will often clash when combined with other ingredients in a cocktail. Sometimes you need to use more of one spirit and less of the other, or one brand of a spirit will work well while another falls completely flat. Patient experimentation is key. And be prepared to be more surprised by what does work than what doesn’t. On paper, aquavit and tequila sound like bitter rivals, but after trying several brands and amounts, Jillian Vose was able to make them best friends in her Enemy Lines, a variation on the Sazerac.

After you grow comfortable with splitting base spirits, try playing around with split modifiers and sweeteners. Eventually you’ll be able to adapt drink recipes extensively, splitting multiple components and watching the ingredient count add up, as in the Shattered Glasser, which contains two base spirits and four modifiers.

Sometimes a new drink will be born out of a simple stroke of inspiration, be it an ingredient, a flavor combination, a song, a movie, a mood, or just about anything else. Such cocktails, created to express a unified idea, are what we call concept drinks.

Whereas Mr. Potato Head, dressing up naked drinks, and splitting base spirits and modifiers are all ways to remodel existing cocktails, concept drinks are created from the ground up. As a result, they require a lot of patience and tinkering to get right. To best illustrate the process of developing a concept drink, we asked Brad Farran, our resident conceptual cocktail artist, to explain the process behind a few of his concept drinks:

“I loved Orange Julius as a kid and wanted to re-create that flavor in a sophisticated cocktail. For a base spirit I started with dry curaçao, which has an orangey flavor, obviously, but also a strong vanilla note, as does an Orange Julius. Then I started playing around with rums as a modifier, particularly rums that could enhance that vanilla flavor. It’s fun to use a modifier as a base spirit and vice versa. After that it was a matter of adding other elements to balance it out: lemon juice for acidity, a little bit of cream for richness, and a teaspoon of Vanilla Syrup to really pump up that flavor. Originally I didn’t include orange bitters in the drink, but when I added them it made it taste a lot more like a cocktail and less like something you might buy at the mall.”

“I love the original Karate Kid movie and decided to create a drink based on Daniel’s signature move. I asked myself, What does the name imply? The answer: Japanese whiskey. I like pairing whiskey with tropical flavors, so I went in a tiki direction. I tried to find a modifier that would showcase the Yamazaki whiskey’s flavor profile, and found it, of all places, in coconut liqueur. Sweetness came from orgeat, another tiki staple, and acidity from a combination of orange juice and lemon juice. At that point the drink tasted fine, but it wasn’t very complex. A teaspoon of peaty Scotch fixed that, resulting in a drink that was graceful yet deadly.”

“I woke up one day wanting one of those strawberry shortcake ice cream bars I’d bought as a kid from the Good Humor truck. I couldn’t find one, so I decided to turn my craving into a cocktail. I knew the hardest part would be getting the malty flavor of the coating into the drink, so I reached for an unaged genever as a base spirit, but it was too malty on its own. So I split the base three ways with bourbon, unaged genever, and barrel-aged genever, which did the trick. Heavy cream and orgeat provided the richness, and Vanilla Syrup added the ice cream flavor. All that was left was the strawberry. It took only a half teaspoon of strawberry liqueur to get all of the flavor I needed.”

We’re constantly discovering new and surprising flavor combinations at the bar. Below you’ll find some of our all-time favorite affinities between various base spirits, modifiers, and fresh ingredients.

GIN Everything (almost), herbs, citrus, aperitif wine, dry vermouth, blanc vermouth, Chartreuse, honey, calvados, bitters, champagne, ginger

VODKA Anything with flavor

AQUAVIT Gin, pepper, pineapple, celery, lemon, blanc vermouth, rye, sweet vermouth, dry vermouth, amari, chamomile, ginger

BOURBON Crème de cacao, honey, grapefruit, figs, apple, cognac, chamomile, rye

CALVADOS Chamomile, clove

APPLEJACK Smoky Scotch, lager

RUM Other rums, maple syrup, coffee, citrus (lime especially), herbs (mint, basil), ginger, curry leaf

TEQUILA Grapefruit, black pepper, yellow Chartreuse, salt, jalapeño, Thai basil, kumquats

MEZCAL Tequila (reposado), bell pepper, strawberry, Suze

SCOTCH (SMOKY) Pineapple, mint, lime

SCOTCH Apples and pears, cinnamon

JAPANESE WHISKEY pineapple, coconut

SHERRY Everything (almost)

DRY SHERRY Gin, cocchi Americano

AMONTILLADO SHERRY American whiskey, citrus, gin, cognac

OLOROSO SHERRY Blended Scotch

DRY VERMOUTH Peach, apricot

CARPANO ANTICA FORMULA Coffee

SWEET VERMOUTH Chai tea

BLANC VERMOUTH Chamomile, watermelon, sage

CAMPARI Chocolate, raspberries, sloe gin

APEROL Blanco tequila, Lustau East India solera sherry, mango, grapefruit

GREEN CHARTREUSE Coffee, chocolate

YELLOW CHARTREUSE Strawberry

AMARO Peach

CYNAR Crème de cacao, celery

ST-GERMAIN Everything

ANGOSTURA BITTERS Aged spirits

ORANGE BITTERS Citrus

GRAPEFRUIT Cinnamon

CELERY Apple

VANILLA Passion fruit, pineapple

STRAWBERRIES Black pepper, cinnamon

CINNAMON Pineapple, pear, vanilla

CUCUMBER Mint, sage

PEACH Honey

PINAPPLE Sage

PEAR Orgeat

KAFFIR Cucumber

SNAP PEAS Gin

CHAMOMILE Yellow Chartreuse, peach

We’d be thrilled if cocktails could somehow name themselves. While it might sound like a badge of honor to christen one’s hard-earned original creation, coming up with a drink’s name is usually the most frustrating part of the process. It’s not as easy as, say, naming a baby or a car. You can’t call a new cocktail Austin and move on. Nay, cocktail names need to be unique. For better or worse, there is only one Manhattan, and there will always be only one Slippery Nipple.

Most of our drinks are perfected long before they have a name, with the exception of a concept drink (explained). If bartenders fail to name their new creations (or give them names inappropriate for public consumption) before our next menu is finalized, the task falls to the head bartender, who often has to assign names to a queue of drinks, Ellis Island style, minutes before the menu is printed.

A very informal audit of our database of more than four hundred original Death & Co cocktails reveals a few commonly used drink-naming strategies.

THE MOVIE NOD Usually a reference to either lowbrow comedy or art-house cinema—rarely anything in between.

Examples: Crane Kick, Strange Brew, Sergio Leone, Blazing Saddles, Coffee and Cigarettes, Cider House Rules, Fair Lady, and Jack Sparrow Flip

THE NOSTALGIA TRIP Childhood favorites for grown-ups.

Examples: Good Humor, Pink Elephant, Camp Council, Little Engine, Dick and Jane, Koko B. Ware, and Rock, Paper, Scissors

THE SCHOLARLY REFERENCE Bartenders showing off how well read they are.

Examples: Dick Brautigan, Night Watch, Sling of Aphrodite, Hadley’s Tears, Porfirian Punch, Myra Breckinridge, The Dangerous Summer, Botany of Desire

THE A SIDE A musical reference that most guests will recognize.

Examples: Cinnamon Girl, The Great Pretender, Rebel Rebel, Heart-Shaped Box, Lust for Life Punch, Dolly Dagger

THE B SIDE An obscure musical reference our guests would love to forget.

Examples: Eagle-Eye Cherry, Dr. Feelgood, Sade’s Taboo, Hallyday, Nina’s Moan

THE GENUS Various cocktails in the same category; often used for variations on classic drinks.

Examples: Cobra Verde, Coralillo, Vipera, Puerto Rican Racer (all variations on the Diamondback)

THE NAME DROP Shout-outs to our heroes, friends, and—perhaps too often—ourselves.

Examples: Gonzalez, Light and Day, Last Ward, Shattered Glasser, Ty Cobbler, the Bittenbender

THE INSIDE JOKE Probably best not to ask.

Examples: Slap ‘n’ Pickle, Stolen Huffy, Angie’s Secret, 202 Steps, Sea B3, B.A.F.

… Death & Co’s Worst Drink Names, Selected by the Staff …

DAI, DAI MY DARLING

DON’T SIT UNDER THE APPLE TREE

ENCHANTED ORCHARD

FAIR FAULT

GLANDULA DEL MONO

LE BATELEUR

LIGHT AND DAY

MEXI-GIN MARTINI

MIG ROYALE

MRS. DOYLE

PADDY MELT

PELÉE’S BLOOD

SADE’S TABOO

SENTIMENTAL JOURNEY

SHORT RIB

SIPPING SEASONS

SLING OF APHRODITE

SUNSET AT GOWANUS

VEJK SLING

TUESDAYS WITH MOLE

YEOMEN WARDER

Amador Acosta has cooked in some of New York City’s finest restaurants, from Gilt with Paul Liebrandt to Tailor with Sam Mason, and is currently the kitchen operations manager and corporate chef at Michael White’s Altamarea restaurant group.

Bartenders take a lot of cues and inspiration from chefs, but the bartenders at Death & Co teach me new ways to marry flavors in the kitchen. It’s fun to sit at the bar and become part of the creative process. I’ll throw out a couple of ingredients or flavors, and they’ll create a new cocktail around them on the spot. They talk about balance, textures, and flavors the same way chefs do in the kitchen. Sometimes they engage me about a dish I’m working on and give me a new perspective on how to put it together.

In many ways Death & Co has become one of the city’s centers of creativity. The bartenders love to experiment and are not afraid to fail. More importantly, they help each other work through ideas. This is how the best restaurant kitchens work, as well. At Death & Co, the customer becomes a key component of the process. The bartenders will share drinks they’re working on and ask guests for feedback, then make it again. The more people you let into the process, the better the final product becomes. Nothing is proprietary, and there’s no need to worry about your idea getting picked up and improved upon by the next guy.

The most important part of the creative process is having a firm understanding of the classics. Without this knowledge, creativity becomes novelty, not innovation. The reason the bartenders at Death & Co excel at innovation is because they have such a strong skill set and understanding of the classics.

I usually come to Death & Co after I’m done in the kitchen for the night, so I get there not long before last call. The old-fashioned is my default cocktail. It has a balance of bitter, sweet, and acidity that I appreciate. Tiki drinks have also taught me a lot about balance. With so many flavors and ingredients coming together in a glass, they are exceptionally hard to make right, yet a properly made tiki drink strikes a harmony you want to keep experiencing.

I tend to avoid clear, stirred drinks. They typically don’t have enough going on for me. But one night Alex introduced me to the White Negroni. It had that balance of bitterness, booziness, and sweetness that I love. I’d already drunk so much that I couldn’t finish my Negroni, so I dumped it into my coffee thermos and threw it in my backpack. The next night I pulled it out at a restaurant and poured it over ice. It was the ultimate roadie drink.

WHITE NEGRONI

1½ OUNCES FORDS GIN

¾ OUNCE DOLIN BLANC VERMOUTH

¾ OUNCE SUZE SAVEUR D’AUTREFOIS LIQUEUR

GARNISH: 1 LEMON TWIST

Stir all the ingredients over ice, then strain into a double rocks glass over 1 large ice cube. Garnish with the lemon twist.

In early 2007, we read a lengthy piece in the New York Times comparing the cocktail scenes in New York City and London. The article started with the proclamation—by an esteemed New York bartender, no less—that “London is the best cocktail city in the world right now.” Phil and I (Dave) had never been to London, so a few months after Death & Co opened we planned a whirlwind tour of London bars to confirm or deny the claim.

The trip influenced more than one aspect of Death & Co. After three days of drinking our way around the city’s best bars—we checked off some twenty-five establishments in all—we agreed with much of what the article said. The baseline for craft cocktails in London was indeed higher than NYC, in that there were more bars using fresh juice, good ice, and intriguing ingredients than our fair city. Still, these were familiar precepts—and ones we already adhered to at D&C. But London also brought us a couple of revelations.

First, we’d been told by New York’s cocktail cognoscenti that a menu should contain no more than twelve drinks. Any more, they warned, and customers wouldn’t be able to digest the content. Plus, the bar wouldn’t be able to maintain a high level of quality and consistency. But in London, cocktail menus were crazy long. Many were exhaustive volumes filled with pages upon pages of drinks, mostly classic cocktails. We thought that if those London joints were able to manage their monumental menus, we could do the same but with our own original drinks. Upon our return, the menu at Death & Co swelled from ten drinks to sixty.

Our second revelation was punch service. At the Hawksmoor, a steakhouse with a bitchin’ cocktail program, we watched as antique punch bowls were brought around to tables and guests were allowed to ladle themselves a drink. We loved the conviviality of punch service. There’s something special about sharing the same drink with your friends and how punch passes the hospitality torch: order a bowl of punch for your table, and you become the host.

Punch predates the cocktail. British soldiers first created it in India in the sixteenth century and brought it back to the United Kingdom, where it became the preferred method of imbibing for some two centuries and spread famously throughout the world. However, nobody in the United States was making traditional punch at the time. What a shame.

Back at Death & Co, we started hunting for vintage bowls while Phil researched punch and began developing recipes. We added a few punches to our next menu, and guests began ordering it in waves. One bowl would go out, other tables would gawk, and the bar would soon be filled with the sound of clinking punch cups. We quickly received a lot of press for our punch program, and other bars took notice. Soon punch was popping up everywhere and being recognized for what it is: a communal drinking experience with deep roots in cocktail history—and fun.

Whenever we develop a new punch recipe, we follow a few guidelines:

• Classic punch contains five elements: spirits, sugar, citrus, water, and spice. The word punch is said to be derived from the Hindi word panch, which means “five,” though recent scholarship calls this into question. (For a full history lesson on punch, read David Wondrich’s thoroughly researched book on the topic; see this page). Tea was traditionally used as the spice component, so we often use a tea-infused spirit or vermouth, as in Mother’s Ruin Punch.

• Sweetener can be added in solid form (granulated sugar or sugar cubes) or as a liquid, in the form of syrups. When creating Death & Co’s first punch recipes, Phil came up with a method in which he muddled sugar cubes with club soda to make an instant simple syrup. He says using cubes makes measuring the sugar easier.

• Punch is always stirred. This breaks the rule of citrus = shaken, but we often finish punch with club soda or sparkling wine to add effervescence, so shaking isn’t required. Instead, the punch is either stirred over ice in a pitcher or rolled (poured back and forth) between two pitchers with ice before straining it into the bowl.

• Punch is almost always served over one large block of ice. This slows down dilution while keeping the drink cold.

• Garnishes are floated in the punch bowl to be added to drinks as guests please.

Making individual cocktails for people, one at a time, is an awful way to spend a dinner party. For entertaining large crowds, we fully support the practice of batching cocktails: premixing them to the extent possible a few hours ahead of time (or even the night before), then chilling the batch and making individual cocktails to order.

Most of batching involves simple math: Take a cocktail recipe, convert ounces to cups (or quarts or even gallons if serving a big crowd), mix, and chill. But there are a few rules of thumb to follow:

• Proportions: If you’re preparing up to five drinks at a time, the balance won’t change dramatically and you can get away with simply multiplying the recipe. But when batching more than five drinks at a time, a funny thing happens with citrus and other acidic ingredients, the sweeteners, and especially the bitters: their effect on the cocktail is enhanced. So you need to use less of these ingredients, by proportion, than in the base recipe. Start with about half the amount called for when you multiply the recipe, then add more to taste.

• Dilution: Don’t forget that roughly 25 percent of a cocktail is water. If you’re mixing ahead of time and refrigerating the batch, dilute it to taste with water just before serving, keeping in mind that any additional dilution that might occur if you’re serving it over ice. A batch of stirred, boozy drinks can be diluted ahead of time and stored in the freezer; the alcohol will keep it from freezing. Shaken drinks should be batched without any added water and shaken with ice to order.

• Bubbles: Any cocktail that gets topped with champagne or another sparkling beverage is great for batching. Prepare the batch ahead of time without the bubbly ingredient, then add it just before you serve the cocktail to brighten it up.

Every night we’re asked—dozens of times—to come up with a “bartender’s choice” for a guest. If we took this request literally we’d rifle through our giant brain databases and offer the guest whatever cocktail we’d randomly fallen upon. Some bars do just this. But we take the responsibility of choosing a cocktail very seriously, and believe that there’s a perfect drink out there for every guest. Finding it, however, requires a few questions and a lot of quick thinking on the part of our bartenders.

The chart below illustrates how Alex Day goes through the process. He generally starts with whatever menu we’re serving at the time, then narrows down the choices from there. For brevity’s sake, we’ve listed the specs of each drink in bartender’s shorthand: each number represents the quantity (in ounces) of each ingredient, and DB stands for “dash of bitters.”

| BELLA LUNA Gin, Shaken |

BLACK MAGIC Brandy, Stirred |

| BLOODHOUND Punch |

BUMBOO Rum, Stirred |

| CHINGON Agave, Shaken |

CORTADO Rum, Stirred |

| CURE FOR PAIN Whiskey, Stirred |

DICK AND JANE Sparkling |

| DOUBLE BARREL Juleps |

EAST INDIA TRADING Rum, Stirred |

| FIX ME UP Whiskey, Shaken |

FLOR DE JEREZ Rum, Shaken |

| GOLDEN BEAUTIFUL Agave, Shaken |

GOLDEN GATE Brandy, Shaken |

| GRAND STREET Gin, Stirred | GREEN FLASH Sparkling |

| HOI POLLOI Brandy, Shaken |

HONSHU Gin, Shaken |

| INGÉNUE Manhattans |

JIVE TURKEY Manhattans |

| KINGSTON NEGRONI Negronis |

KOKO B. WARE Rum, Shaken |

| LAST TRAIN TO OAXACA Agave, Stirred |

LITTLE MISS ANNABELLE Brandy, Shaken |

| MORFEO Sparkling |

NORTH GARDEN Old-Fashioneds |

| ONE, ONE, ONE Aquavit |

PEARLS BEFORE SWINE Flips & Fizzes |

| PELÉE’S BLOOD Rum, Shaken |

PENDENNIS CLUB Classic |

| PRESSURE DROP Gin, Stirred |

PRIMA CHINA Agave, Stirred |

| QUEEN PALM Gin, Shaken |

RACKETEER Juleps |

| ROBERT JOHNSON SWIZZLE Swizzles |

ROB ROY Classic |

| SLAP ‘N’ PICKLE Aquavit, Shaken |

SOUTHERN EXPOSURE Agave, Shaken |

| STRANGE BREW Gin, Shaken |

STRAW DOG Whiskey, Shaken |

| VALLEY OF KINGS Punch |

YAMA BLANCA Agave, Stirred |

| ZIHUATANEJO Juleps |

|

BLACK MAGIC Brandy, Stirred 1, 1, ½, 1 tsp, 1 tsp, absinthe |

BUMBOO Rum, Stirred 2, 1 tsp, 1 tsp, 3 DB |

| CORTADO Rum, Stirred 2, ½, ½, ¼, ½ tsp, 2 DB |

CURE FOR PAIN Whiskey, Stirred 1½, ½, ½, ½, 1 tsp, 1 tsp |

| DOUBLE BARREL Juleps 1½, ½, 1 tsp, 1 tsp, ¼, 4 DB |

EAST INDIA TRADING Rum, Stirred 2, ¾, ½, 2 DB |

| GRAND STREET Gin, Stirred 2, ¾, ¼, 1 tsp, GF twist |

INGÉNUE Manhattans 2, 1, 1 tsp |

| JIVE TURKEY Manhattans 1, ¾, ¾, ¾, ¼, 1 DB |

>KINGSTON NEGRONI Negronis 1, 1, 1 |

| LAST TRAIN TO OAXACA Agave, Stirred 1½, ¾, ½, 1 tsp |

NORTH GARDEN Old-Fashioneds 1½, ¾, ¼, 1 tsp, 1DB |

| ONE, ONE, ONE Aquavit 1, 1, 1, DB |

PRESSURE DROP Gin, Stirred 1½, 1, ½, 1 tsp, 1 DB |

| PRIMA CHINA Agave, Stirred 2, ¾, ¼, 1 barspn, 1 DB |

RACKETEER Juleps 2, ½, 1 tsp, 1 tsp, 1 DB |

| YAMA BLANCA Agave, Stirred 1½, ½, ¾, ¼ |

ZIHUATANEJO Juleps 2, 1 tsp, ½ float |

| GRAND STREET Gin, Stirred 2, ¾, ¼, 1 tsp, muddled GF twist; coupe glass |

ONE, ONE, ONE Aquavit 1, 1, 1, 1 DB; Nick & Nora glass |

|

PRESSURE DROP Gin, Stirred 1½, 1, ½, 1 tsp, DB; coupe glass |

1 GRAPEFRUIT TWIST

2 OUNCES BEEFEATER LONDON DRY GIN

¾ OUNCE PUNT E MES

¼ OUNCE CYNAR

1 TEASPOON LUXARDO MARASCHINO LIQUEUR

In a mixing glass, gently muddle the grapefruit twist. Add the remaining ingredients and stir with ice, then strain into a coupe. No garnish.

Anthony Sarnicola currently works as a technical project manager for an investment bank. Regina Connors is an independent consultant working with the financial industry.

ANTHONY My first experience here was not inside the bar. We lived in the neighborhood at the time, and I was out for a walk on a Saturday night. There was a huge line outside and a door guy. I thought that this was one of those places with an annoying door policy; for example, only the pretty people are allowed inside. But after stalking the door for a while, I realized that it was a completely egalitarian process. So I came back on a Wednesday as soon as they opened (6 p.m.), when there was no line. The first thing I noticed was that they had a bunch of ryes behind the bar. I asked the bartender, Joaquín, to make me a few different Manhattans, with a different rye in each. He obliged. My second trip there I ordered another Manhattan. Joaquín asked me if I’d ever had an Old Pal. That was the beginning of the end.

REGINA The first time I came in I’d just arrived home after a long flight. Anthony dragged me over and said, “You’ve got to taste these drinks.”

ANTHONY I remember being served a Fog Cutter that night. I got about a quarter of the way through this tall, seemingly froufrou cocktail and said to Regina, “I must be a lightweight; I’m fucking buzzed already.” Brian heard this and laughed, then said, “Dude, there’s 6 ounces of rum in that drink.”

REGINA Once the bartenders understand your palate, they like to broaden your horizons. I generally like my drinks not too boozy, whether they’re shaken or stirred. While I like bitter drinks, Campari is not to my taste—ever. I loathe it. But I have to give the bartenders credit. They love to sneak Campari into drinks, and sometimes it helps me appreciate a new aspect of the spirit.

ANTHONY My usual now: brown, stirred, boozy—up or rocks; don’t care.

REGINA I’ve lived and drunk in this city for decades and have had many fun experiences socializing with strangers. But Death & Co is unique in that the socializing has been around the drinks: the flavors, the shared sips, the shared stories that follow. On so many occasions the bonding led to friendships that lasted beyond the evening.

ANTHONY My favorite moments at Death & Co all revolve around the crowd and the random conversations you have with strangers. You meet people who have come to see what everyone’s been talking about, who come to have some transcendent drinking experience. You meet people who are celebrating their twenty-first birthday and have decided that this is where they want to have their first proper cocktail.

REGINA After Death & Co’s first anniversary they had some of the regulars’ names engraved on silver plaques on the back of the bar stools. Dave grabbed us and went around the bar with a lighter to show us our names.

ANTHONY He held up a lighter under people’s asses saying, “Excuse me, excuse me,” until he found our stools.

OLD PAL

1½ OUNCES RITTENHOUSE 100 RYE

¾ OUNCE CAMPARI

¾ OUNCE DOLIN DRY VERMOUTH

GARNISH: 1 LEMON TWIST

Stir all the ingredients over ice, then strain into a Nick & Nora glass. Garnish with the lemon twist.