1926

Like the year that has preceded it, 1926 will be another period of extreme gang violence, which for McGurn becomes much more personal. With the vengeful North Siders decidedly ridding the world of the Genna brothers, Capone gladly accommodates McGurn by ordering the executions of the Gennas’ most effective killing crew. Bossed by Orazio “The Scourge” Tropea are Vito Bascone, Ecola “The Eagle” Baldelli, and Phillip Gnolfo, four of the names that had also been mentioned in the murder of Angelo DeMory.1 Tropea, Bascone, and Baldelli have been long suspected of sending Black Hand letters to people in the Sicilian neighborhoods in their brutal extortion business.

McGurn is no doubt thrilled on getting word from Al Capone that the very men he wants to kill the most are sanctioned for death. It is a busman’s holiday to be paid to do what he will relish, although to avenge his stepfather he would probably work pro bono. There is no known record of how much McGurn makes, but the assumption is that he is paid a high salary and frequently an additional bonus, all in cash. He is already Capone’s favorite boy, treated preferentially by the Big Fella.

For these murders, McGurn partners up with movie-star-handsome Johnny Armando, one of the gunners who is associated with the Jewish gangsters and politicos around Maxwell Street. Armando is the size of a horse jockey, a bantamweight at five-four and 120 pounds, but he is as lethal as he is diminutive. He is normally employed in the fiefdom of Twentieth Ward boss Morris Eller, whose son Emanuel is a circuit-court judge. They are a politically powerful family with strong ties to Johnny Torrio and now Al Capone. Eller, with interests in bootlegging, also supports the extinction of the Genna organization. Armando is likely Morris Eller’s contribution to the workforce that is finishing off any Genna men who might try to seize power.

Jack McGurn, 1926. PHOTOGRAPH BY ANTHONY BERARDI

The boyish murder team of Jack and Johnny take out the serpent’s head first when they shoot down Orazio “The Scourge” Tropea on February 15.2 Tropea is the most dangerous Genna killer, believed to have the malu occhiu, the evil eye, by the more superstitious residents of Little Italy. The Scourge owns a café where his old-world-style Black Hand extortion plots are hatched, including the one that took Angelo DeMory’s life in 1923. He walks with impunity, with the cloak of fear, the kind of pride that comes before a fall. He is almost completely unaware when Armando and McGurn drive their automobile slowly by him. A twelve-gauge shotgun opens up from the passenger seat, blowing away Tropea and both his evil eyes.

The press calls Tropea’s murder part of an “alcohol gang vendetta,” connecting it to the murder a month earlier of gangster Henry Spingola. Words such as “vendetta” and “Mafia” are used because these murders are occurring in the neighborhoods of the Gennas, which the papers have long associated with old-country Sicilian criminals. Spingola, who was shot sixteen times outside Amato’s Restaurant, a favorite haunt for Italian opera singers, was a brother-in-law of the Gennas.3 That Tropea, who is suspected in the Spingola shooting, is murdered himself leads the police to suspect that Little Italy is blowing up with internal, unfinished Genna business. McGurn utilizes this natural distraction and subterfuge to do his business, which the law will only realize in retrospect.

Next on McGurn’s death list is Vito Bascone, another of Angelo DeMory’s suspected slayers. Bascone, a wine dealer and amateur opera singer, also frequents Amato’s. He is friendly with visiting opera stars as well as members of the Chicago Civic Opera Company, such as tenor Tito Schipa. He is often seen with Desire Beirere, the baritone stage manager of the Civic, and Giacomo Spadoni, the assistant conductor. However, underneath this cultural cladding, he is a killer and a thug or, as the police put it, “he conferred in the councils of the Mafia, where the deaths of enemies were plotted.”4

McGurn and Armando know just where to find singing Vito; they pick him up off a street corner and take him for what will become known as the one-way ride. His body, with several bullets in his head, is found out on the suburban prairie, west of the city, on Sunday morning, February 21. Two revolvers are dropped near the body.5

Bascone is widely known to be a close friend and business associate of Tropea. The police are puzzled. This was supposed to be one thing, but it smells like another. These colorful Mafia characters (Bascone has a second, previously unknown wife who appears at his funeral) with Italian and Sicilian names seem to be lining up in the Cook County morgue. Somebody is killing them in obvious competition for booze, but the growing constant and methodical nature of the shootings is unsettling.

The citizens of Little Italy now avoid spending time on the streets for fear of getting caught in a gang shooting. The automobiles of the day tend to backfire, emitting blackish smoke with what sounds like a gun report. People visibly react whenever this happens—the common event is usually followed with a nervous laugh.

McGurn waits only forty-eight hours to kill Ecola “The Eagle” Baldelli, who is found on an ash heap in an alley with many bullets in his body. The Eagle was Tropea’s driver; he probably drove the automobile on the day Angelo DeMory was killed. Along with the combination of .32 revolver and .38 automatic bullets in his body, Baldelli has been given “the buckwheats,” 1920s gangster jargon for a hideous thrashing. His body is bruised and beaten. McGurn gets some personal revenge for his stepfather with a serious pummeling before he and Armando empty their guns into the Eagle.6

In Baldelli’s pocket, the police find a return application card for the Chicago police department, which had been filled in. They theorize that the Eagle was killed by his fellow gangsters because he was going to join the police force. Apparently, with everybody dying around him, Baldelli was thinking of seeking refuge in the safest place he could imagine. This really confuses the detectives. A huge dragnet is launched; police begin raiding every blind pig, speakeasy, fruit stand, grocery, and storefront on the West Side. Consequently, a hundred men are picked up for questioning. The public is demanding protection, and the quickest way to make it look like something is being done is to simply roust anybody who “looks suspicious”—an action that turns into a mass law-enforcement profiling in which dozens of Italian and Sicilian immigrants are summarily carted to the lockup.7

The remnants and supporters of the Genna Outfit, as well as the North Siders led by Hymie Weiss, are now all aware of the dangerous role that Jack McGurn plays in the Capone organization. On March 2, somebody sends four men to kill McGurn. Cruising the West Side in their large touring sedan, they spot McGurn in the alley behind his mother’s apartment at 622 South Morgan Street. Three of them emerge from the car and pull revolvers, but McGurn is too fast and too lucky for them, ducking as they blow his hat off his head. These were either Genna loyalists or North Side gunmen, possibly the Gusenberg brothers, Frank and Pete. If it was the Gusenbergs, they will find it hard to believe the future consequences of their ill-aimed shots. They are the opening salvo in an escalating private war with the baby-faced Jack McGurn, whom they have tremendously underestimated.8

McGurn escapes the failed attempt and is eventually found by the police several hours later. After being questioned, he is unable to offer any reason for the attack. This time he reports his name as James Gebhardt, his address as 1230 Oregon Avenue. He claims he was walking in the alley behind the apartment of his “mother-in-law, Mrs. Josephine Memony [sic], at 630 South Morgan Street.” None of this is remotely accurate, but by this time the innocent immigrant act is probably gone. McGurn has Al Capone and his crack lawyers behind him now. He no longer finds it necessary to give lip service to anyone, especially to Chicago policemen, many of whom are on Capone’s payroll anyway.

This assassination attempt results in McGurn’s first mention in a newspaper in his role as gangster. It will become customary for the press to pick up the lies and misinformation that McGurn feeds to the police. On this particular day, he doesn’t fool the Tribune reporters in the least; they identify him as “formerly a pugilist known as Jack McGurn.”

With the war heating up between the South Side and North Side gangs, McGurn is already targeted by Capone’s enemies. His reputation begins to spread throughout the underworld of Chicago. With each successive killing he gains new adversaries, including the possibility of vengeful relatives. He is quickly becoming an integral part of the familiar gangland death cycle. There are already a score of candidates who would prefer to see him dead.

The very next day, March 6, McGurn is suspected of killing Joe Calebreise, aided by John Scalise and Hop Toad Guinta.9 The Chicago police also suspect him of killing Joseph Staglia and Jeffrey Marks on March 17, aided by Myles O’Donnell.10 Each one of the targets is associated with North Side beer sellers. There are no witnesses, at least none who will admit to it after finding out who the person is in the police mug shots they are shown. Fear overwhelms the moral imperative in every case. The killings are all committed with revolvers, which are dropped at the scene. The guns are picked up for evidence and will eventually undergo new forensics testing, but this does not occur until 1929.

On March 18, Murder Twins John Scalise and Albert Anselmi receive the most outrageous acquittal in Chicago judicial history. In their first trial they were found guilty of shotgunning police officer Charles Walsh during the shootout that killed Mike Genna. They were sentenced to fourteen years. In their second trial, for the murder of officer Harold Olsen, Capone lawyers pull off a dark miracle. Defense attorneys Thomas Nash, Michael Ahern, and Pat O’Donnell are able to convince the jury that Anselmi and Scalise were within their rights to self-defense when they killed the policemen.

When the judge, William Brothers, reads the verdict, Anselmi performs a strange gesture: he half rises from his chair and bows to what the press will call “the cop-hating jury.” Both killers then shake hands with the jurors, who all smile warmly. It is the worst insult to policemen anyone can imagine; even the bent cops on the gangster payrolls are angry. This is the beginning of the idea that nothing and nobody is sacred in Chicago.

A Tribune photographer snaps a picture of the Murder Twins personally thanking the members of the jury, setting off a flashbulb. Since photographs have been prohibited by Judge Brothers, the only person going to jail will be the photographer, whom Brothers sentences to ten days for contempt of court.11 This shocking verdict will aid Capone attorneys in winning a reversal of the first conviction; killers Scalise and Anselmi are free to go back to work for Capone and McGurn.

In April, the beer wars escalate. The Sheldon gang is shooting at the O’Donnell gang, with Capone’s people adding their own contributions to the mayhem. This all leads up to the April 13 primary, in which the slate of candidates aligned with state’s attorney Robert Crowe are all supported by the Outfit gangs, who honor a truce for the duration of the voting. Capone has already learned to live with Crowe out of necessity.

Crowe’s assistant, young William McSwiggin, is a dynamic attorney who grew up with several of the gangsters on the North Side. He loves publicity and has been part of many of gangland’s most famous cases. He eventually was the one who interviewed Capone about the murder of Joe Howard in 1925. He got himself appointed to the investigation of the O’Banion murder and suspiciously helped in the weak prosecution of Anselmi and Scalise in their second trial for the shootings of the two police officers. Along with his triumphs, there are rather interesting failures, such as when he unsuccessfully prosecuted Myles O’Donnell and Jim Doherty for the murder of gangster Eddie Tancl. McSwiggin is the gangster Doherty’s boyhood chum. It is clear that McSwiggin, though Robert Crowe’s right hand, smoothly plays both sides. He appears to be Chicago’s best and brightest assistant state’s attorney, but his duplicitous loyalties put him directly in harm’s way.

This culminates when, on April 27, McGurn helps Al Capone and Louis “Little New York” Campagna make a significant error in judgment: they kill the wrong man. It will exhibit to the world that nobody is immune to gang retribution. Capone’s gunman Willie Heeney spots rival bootleggers Jim Doherty, Thomas “Red” Duffy, and archenemy Myles O’Donnell in a green Lincoln sedan; Myles O’Donnell is on Capone’s short list. Willie calls Capone, who has allegedly been drinking. The boss rushes the boys out in several cars to intercept Heeney, who is trailing O’Donnell’s automobile. Tommy Ross, a relatively new Capone driver, grabs the wheel, with McGurn, Campagna, and Capone seated in the Cadillac with a Thompson and a fifty-round drum.12

They spot Heeney, who is following the Lincoln, near Madigan’s Pony Inn at 5615 Roosevelt Road. Doherty and Duffy, a Crowe precinct captain in the Thirtieth Ward, step out of the car, along with their surprise guest, assistant state’s attorney William McSwiggin, who isn’t recognized by Capone and his boys. McSwiggin is out for the evening with his chums, never suspecting that he has picked the absolutely worst night to be in their company.

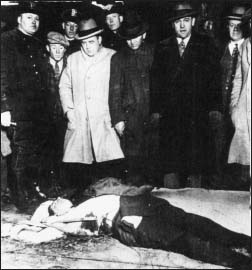

It is either McGurn or Capone himself who mows down Doherty and the two others. Only one Thompson is used, the barrel sticking out the window of the Cadillac, which Mrs. Bach, who lives above the Pony Inn, describes as something that “looked like a telephone receiver spitting fire.”13 Duffy is seriously wounded, but he is able to crawl behind a tree in an empty lot. Doherty dies instantly, cut nearly in half by sixteen of the bullets, while young Bill McSwiggin absorbs his share and crumples to the ground, also dead.

The Capone cars speed off as Ed Hanley, the driver of the green Lincoln, and Myles O’Donnell raise themselves from the floorboards, emerge, and haul the riddled corpses of Doherty and McSwiggin into the backseat. They dump the bodies in suburban Berwyn and the bloodspattered Lincoln in Oak Park.

When Capone finds out it is McSwiggin whom he killed, it is too late for damage control. The papers are screaming the question “Who Killed McSwiggin and Why?” This particular murder is unnerving because the young fireball was a respected and honored state’s attorney. The ensuing investigation by Robert Crowe will last for many months as McSwiggin’s entire life is examined with the scrutiny of a microscope. Eventually, Capone will tire of the huge public debate over McSwiggin’s duplicitous activities. In 1928 he will tell the reporters, “I paid McSwiggin. I paid him a lot and I got what I was paying for.”14

William McSwiggin dead, 1926. COLLECTION OF JOHN BINDER