1936

Even with McGurn interred in Mount Carmel, the bloodshed isn’t finished. Perhaps his worst mistake in the last years of his life is to drag his young stepbrother Anthony into his activities. Anthony idolizes Jack, desiring only to follow in his footsteps. If McGurn had been a simple tailor, Anthony would have become proficient with a needle and thread. Although he is a DeMory, he even takes McGurn’s real name of Gebardi. From the perspective of the Gebardi-DeMorys, McGurn’s murder expands into a double tragedy when twenty-four-year-old Anthony is shot to death in a scenario that is very similar to the shooting of McGurn. It occurs two weeks after his stepbrother is killed.

Anthony is apparently quite vocal after burying McGurn, muttering about revenge and payback for the killers.1 He utters these words of bravado in the wrong places, where the walls have ears. The threat to Frank Nitti reaches the Morrison Hotel. Nitti understands the Sicilian code; in the old country, when a man is murdered, the same fate is shared by the remaining male members of his family. Otherwise, it is incumbent on the surviving father or brothers to seek revenge. Anthony’s youth and Sicilian machismo will be his undoing, for Nitti and the Outfit will eliminate him before he gets the chance to come back at them or relay to others any of the proprietary information McGurn might have entrusted to him.

On the evening of March 2, 1936, Anthony is playing cards in a pool hall at 1003 West Polk Street, near his mother’s apartment on Morgan Street. There are approximately twenty people in the place. Anthony is playing rummy with Santo Cudia, the proprietor of the hall; his friend John Lardino; and Sam “Bobo” Nuzzio, another of his card buddies who is also a Twentieth Ward Democratic precinct captain and an employee of the county assessor’s office. Lardino and Cudia are facing the door; Anthony is sitting with his back to the entrance, always a poor idea for a wannabe gangster.2

At 8:08 PM, three men burst in, the brims of their hats down low, holding guns and handkerchiefs to their faces. One man guards the door while the other two walk up to the card table. In almost exactly the same manner as the killing of Jack McGurn, one of the men announces, “This is a stick-up!” Everybody dives for the floor, but Anthony stands up, puts his hands in the air, turns and faces his killers in a gesture that conveys either a chilling sense of resolve or machismo symptomatic of his undoing. It is as if he knows they are really there for him.

One of the gunmen opens up with a .38-caliber revolver; the first shot severs Anthony’s watchstrap from his wrist and continues into his neck. The watch stops as it falls, dutifully recording the time of death. Another shot is fired, and Anthony drops to the floor. The other killer then empties a .45 automatic into his prostrate body. There are a total of nine bullets in his head, neck, torso, and arms.3 The three killers run back out the door and into a waiting automobile, which speeds west down Polk Street.4 In seconds, all twenty of the patrons vanish in the familiar postmurder exodus.

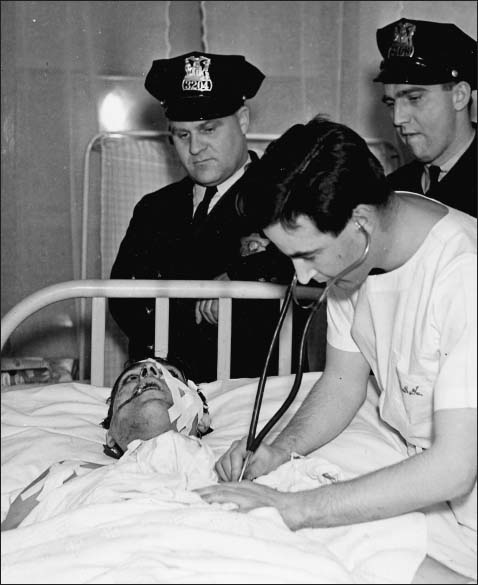

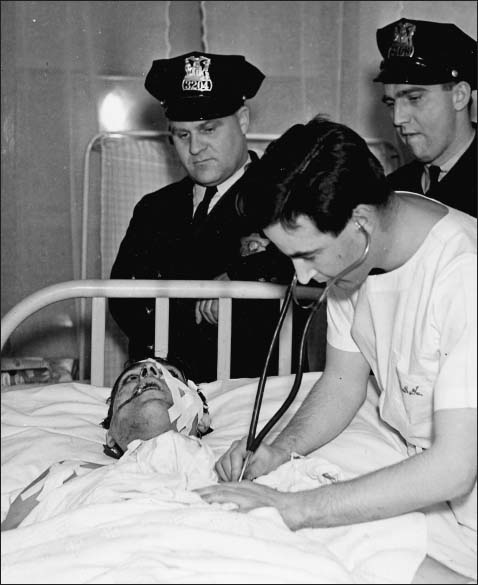

Eighteen-year-old Joseph DeMory, who is near the front of the room playing pool, picks up his unconscious brother Anthony with the aid of two friends. They carry him a block and a half to Mother Cabrini Hospital, leaving the proprietor, Cudia, alone in his blood-spattered poolroom. Joseph then dashes home to his family’s apartment, where police officers later find him with his mother, Josephine, and his twenty-three-year-old sister, Angeline, who are sobbing hysterically. Anthony never regains consciousness and dies on the operating table an hour later, after press and photographers appear, snapping a picture of the expiring youth.

Anthony Gebardi-DeMory dying, 1936. COLLECTION OF JOHN BINDER

Police take young Joseph to the station for questioning. Inconsolable, Josephine and Angeline throw their arms around Joseph as if to keep him with them. They say to the police officers, “They want to get him too. Take care of him!”5

Just after midnight, Louise Rolfe McGurn arrives at the morgue with her brother-in-law, Frank Gebardi. They identify Anthony’s body—the second time in two weeks that they have watched a coroner’s assistant remove the sheet from their loved one’s face. This is nearly as devastating for Louise as McGurn’s death. She leaves sobbing; a Twenty-Second District policeman snidely comments to the Daily News reporter, “She may be next.”6

An hour after the shooting, Emma Lozano, a housewife who lives at 655 South Aberdeen Street, discovers the .38 revolver used to kill Anthony. It is lying near the sidewalk at the corner of Sholto Street and Vernon Park Place. She immediately takes it to the Twenty-Second District police station. An hour after that, fifteen-year-old Tony Lattanza and his friend Danny Grecco find the discarded .45 automatic near a vacant lot on Sholto Street and also bring it to the police station.

The serial numbers have been filed off the revolver. Sergeant Frank Ballou, who has examined dozens of murder weapons, finds the “secret” serial number inside the frame of the gun. This number and the still-extant serial number of the Colt .45 automatic are wired to the Colt Firearms Company in Hartford, Connecticut, to trace the original ownership. Both guns are immediately handed over to Calvin Goddard for ballistics testing. Since shortly after the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, Goddard has moved his entire forensics laboratory to Northwestern University in downtown Chicago to be near the center of the gangland storm.

After examination of the weapons and bullets at the Northwestern lab, Major Goddard determines that Anthony Gebardi and representative Albert Prignano, who was killed back on December 29, 1935, were murdered with the same Colt revolver. The police trace the gun to the Palace Loan Bank, the Depression-era name for a pawnshop, in nearby Gary, Indiana, where it was purchased in 1930 under a fictitious name.7

The best evidence that McGurn was killed by the remnants of the Capone Outfit is contained in this forensic epiphany. Captain John Egan of the Maxwell Street station, who is supervising the investigation, also concurs. He declares that there is strong evidence that the murders of Prignano, McGurn, and Anthony Gebardi have a “common origin.”8 He is probably in the know, for FBI director J. Edgar Hoover will note in a memorandum in 1937 that Egan himself was on the Capone payroll and received five thousand dollars a week.9

The coroner’s inquest into the murder of Anthony Gebardi is convened on March 4 at 10:30 AM and conducted by assistant coroner James J. Whalen. A coroner’s jury of six is sworn in. Representing Anthony’s interests is assistant state’s attorney John J. Phillips.

The first witness is Frank Gebardi, who last saw his stepbrother on the Thursday before he was killed. The most important part of his testimony is that he is a full brother to Jack McGurn and a stepbrother to Anthony Gebardi, thus confirming that Josephine Gebardi had indeed linked up with Angelo DeMory at least nine months before Anthony’s birth in 1915. However, Frank has distanced himself from both of his brothers’ criminal activities and knows nothing about Anthony’s murder.

Next to be called is Officer T. J. Nolan of the Twenty-Second District station. He testifies that he and his partner answered a radio call and responded to the poolroom, where they found owner Santo Cudia standing over a huge pool of blood. Anthony had already been taken to the hospital, and the other patrons were long gone. Nolan offers absolutely nothing that is helpful.

By this time, the news of the weapons having been brought in changes the order of the hearing. Captain Egan announces that the police need to examine this new evidence. Consequently, the inquest is postponed until March 25 to give them more time.

In the final inquest session, Anthony’s friend of seven years, John Lardino, is called to testify. He relates that his mob moniker is John Alcock. It is suspected that he was a bodyguard to Jack McGurn during McGurn’s last year of life. Even though Lardino witnesses Anthony’s murder, he is purposefully evasive, only answering the most basic questions put to him by the deputy coroner and the state’s attorney. He is eventually excused, having contributed no useful facts.

The next to be called is Santo Cudia, the Sicilian owner of the pool hall. In his broken English, he explains that Anthony began coming into the hall about six months before, just after Cudia opened his business. Even though he too witnessed the shooting, he is unable to identify the killers. When he is asked what he was doing while the gunmen were firing, he answers, “Well, I sat in my chair, that is all. I no talk to them. Nobody talk to them.”10 Unable to shed any light on the murder, Cudia is also excused.

Lozano testifies about how she found one of the murder weapons, although it doesn’t help in suggesting who the shooters might be. After she is excused, Officer Nolan is recalled. He claims that the testing of the gun and the ballistics is continuing, and that he isn’t certain if the investigation has been completed. Deputy Coroner Whalen—frustrated and knowing full well that he is once again facing a Sicilian standoff—allows the medical examiner, J. J. Kearns, to summarize. The inquest is then formally brought to an end. The verdict, of course, is that Anthony DeMory, also known as Gebardi, was shot to death by persons unknown.

At this time there are four remaining Gebardi-DeMory sons. Josephine is completely terrified that the Outfit and those responsible for her boys’ deaths will take Anthony’s oath of revenge as a traditional Sicilian vinnitta. She immediately goes to Teresa Capone for help. Al’s mother still has quite a bit of clout with Frank Nitti; she asks for an audience for Josephine, which is granted. An anonymous source who is quite close to the DeMory family suggests that during their meeting, Josephine pleads for her remaining sons’ lives. She makes a promise that none of the boys will ever become involved in any illegitimate enterprise, nor will any of her family members even consider seeking revenge for the murders of Jack and Anthony. In a merciful gesture, Nitti, without confessing to any complicity, lets Josephine DeMory know that he will do whatever he can to ensure the safety of her surviving sons. In so many words, both uttered and unspoken, the deal is made; Nitti will keep his word.

Joseph DeMory will die in the Pacific on June 12, 1942, in the service of his country.11 Frank, the last true Gebardi brother, will live into his eighties, dying of natural causes in 1989. The other family members will live out their lives in obscurity, leading a normal existence and bringing honor to their parents and grandparents. Josephine Verderame Gebardi DeMory will pass away in 1939, a beloved matriarch, at eternal rest with her family in Mount Carmel.

The section where they are buried is still tenderly supplied with red geraniums on their gravestones. The tree that was a tiny sapling in 1936 is now a mature, protective arbor that gives shade to the Sicilian American family resting near it. It is not a “gangster attraction” but a sacred place, as are all cemeteries, and should remain exempt from the inelegant visitations of the curious. It should also be reiterated that Vincent and Anthony Gebardi were but two members of a sizable brood who contributed myriad good things to their city and their country. They had children, grandchildren, and now great-grandchildren, who are all bonu comu pani, as good as bread.