In March 1945, the Rhine River was the last major geographic barrier to the Allied assault into western Germany. The Wehrmacht, bled white by horrific losses in personnel in the winter of 1944–45, pinned its hopes on the Rhine as the final defense line of the Third Reich. The capture of the Ludendorff railroad bridge at Remagen on March 7, 1945, provided the Allies with their first bridgehead over the Rhine. The capture was a surprise for both sides. The Wehrmacht had been demolishing all the Rhine bridges to prevent their capture and expected that the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen would be destroyed as had the others in the area. The Allies were already planning major operations to seize a Rhine bridgehead by amphibious assault, but in more favorable terrain north and south of Remagen. The unanticipated windfall at Remagen provided welcome opportunities for the US Army and significantly changed Allied planning for the endgame against the Third Reich. Instead of the deep envelopment of the vital Ruhr industrial region planned since the autumn of 1944, Bradley’s 12th Army Group was able to conduct a much more rapid shallow envelopment, trapping Army Group B in the process. Hitler ordered Army Group B to defend the Ruhr instead of retreating to more defensible positions in central Germany, speeding their defeat. The destruction of Army Group B removed the most significant German formation in the west and hastened the end of the war. By early April, Eisenhower shifted the focus of the Allied offensive into Germany with Bradley’s 12th Army Group as the vanguard into central Germany rather than Montgomery’s 21st Army Group.

The German counteroffensive in the Ardennes in December 1944 had delayed Allied plans to close on the Rhine, but at the same time the costly battles of attrition in January 1945 had decimated the Wehrmacht in the west. The German plight was further amplified by the Soviet winter offensive along the Oder River in January 1945, which forced the Wehrmacht to transfer some of its best forces, such as Sixth Panzer Army, to the east. The Soviet onslaught in Prussia and eastern Germany led Hitler to insist that the primary theater would be the east and that the Wehrmacht in the west would be limited to defensive operations. The defeat of both the Ardennes offensive and the subsequent and smaller Operation Nordwind in Alsace had made it clear, even to Hitler, that the Wehrmacht had few prospects for any military miracles in the west. As a result, in February 1945 Hitler committed his last reserves to a hopeless offensive in Hungary. The Hungarian operation was intended to relieve the besieged Budapest garrison and to serve as a springboard to strike north, trapping the Red Army with a simultaneous strike southward from East Prussia. The offensive was a costly failure and left the Wehrmacht in a perilous state with no substantial reserve of mobile forces to meet forthcoming Allied offensives, east or west.

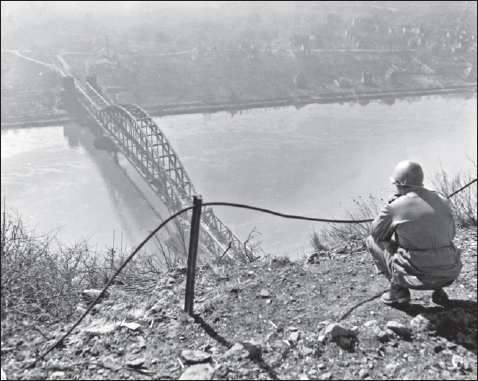

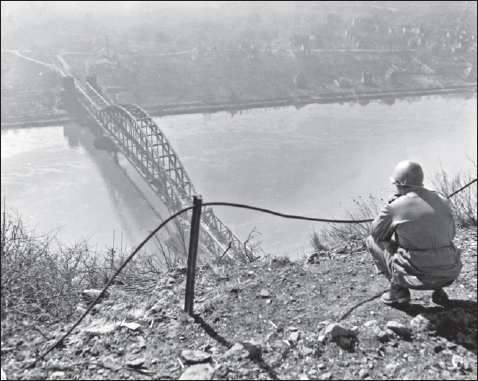

The capture of the Ludendorff railroad bridge over the Rhine at Remagen changed the dynamics of the final battles for western Germany in March and April 1945. This is a view of the bridge on March 15, 1945, from the Erpeler Ley looking westward towards the town of Remagen on the other side of the river. (NARA)

As Supreme Commander of Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) in the west, Gen. Dwight Eisenhower had begun to clarify his plans for upcoming operations at the end of January 1945. The Rhine River was the last substantial geographic barrier to Allied entry into Germany’s industrial heartland in the Ruhr and the Saar, so planning hinged around this goal. Ever since September 1944, it had been the cornerstone of Allied plans that Montgomery’s 21st Army Group would be the vanguard of the Allied push into the Ruhr, first with Operation Market-Garden and, after its failure, with a Rhine-crossing operation on the northern side of the Ruhr. This strategic approach had become so widely accepted among Allied strategists that it had become known simply as “The Plan.” With the Rhine now within Allied grasp, Eisenhower began to fine-tune the details of how this campaign would be conducted. His intent was to conduct a three-phase operation to breach the German defenses along the Rhine. The first phase of the plan was to close on the Rhine north of Düsseldorf in anticipation of the main Rhine crossing in the sector of Montgomery’s 21st Army Group. The second phase was to close on the Rhine from Düsseldorf south, in anticipation of a secondary operation by Devers’ 6th Army Group on the lower Rhine. The third phase would be the advance into the plains of northern Germany and into central-southern Germany once the Rhine was breached. Montgomery and the British Chiefs of Staff contested Eisenhower’s plans as they favored a single thrust by Montgomery’s 21st Army Group, reinforced with US corps. Eisenhower opposed this approach fearing that a single thrust offered the Germans an opportunity to concentrate their reduced resources. A secondary crossing on the lower Rhine forced the Germans to spread out their meager forces and made them more vulnerable to Allied operations. As a concession to British concerns, Eisenhower’s formal proposal to the Combined Chiefs of Staff on February 2, 1945, revised the plan so that the main thrust in the north would not be held up by an effort to close on the Rhine in the other US Army sectors. In the event, the US Army was able to close on the Rhine prior to Montgomery’s river-crossing operation.

The critical first step for the US First Army to reach the Rhine was to first cross the Roer River. Here, GIs of the 84th Division, part of XIII Corps, move up engineer assault boats to cross the Roer on February 23, 1945, during Operation Grenade. (NARA)

Underlying these arguments were issues of national prestige. By 1945, the British Army was a dwindling force because of manpower shortages, barely able to maintain its current order of battle in Northwest Europe. In contrast, fresh US divisions were arriving every month and by early 1945, the US Army fielded the majority of Allied divisions. Montgomery controlled the equivalent of about 21 divisions including several Canadian and one Polish division. Of the other 94 Allied divisions under Eisenhower’s command, 11 were French and 62 were American. On the one hand, Montgomery attempted to guard British interests and prevent the British Army from being pushed off into a secondary mission in the final stage of the war against Germany. On the other hand, Montgomery’s lack of fresh British infantry divisions forced him to ask Eisenhower to detach corps and divisions from Bradley’s 12th Army Group to make up for shortages to conduct his ambitious operations. In February 1945, Montgomery was still clinging to Simpson’s US Ninth Army, which had been detached to his command during the Battle of the Bulge. This transfer of troops from US to British command caused growing resentment in Bradley and other senior US commanders. But at the same time, it reduced Montgomery’s bargaining power in dealing with Eisenhower who was growing increasingly weary of Montgomery’s insistence on employing the 21st Army Group as the centerpiece of all major Allied offensives. During the debate over the Rhine plans, Eisenhower was taken aside by the US Army Chief of Staff, George C Marshall, and assured that the Combined Chiefs of Staff would accept his plans regardless of the complaints by the British Chief of Staff.

Eisenhower’s plan specifically ignored any possibility for a Rhine crossing in the sector of the US First Army east of the Ardennes, the site of the future Remagen operation. The reason was the terrain and not politics. Moving east out of the Ardennes into Germany, the hilly and forested terrain blended into the rugged and forested Eifel region. Even beyond the Eifel and on to the Cologne plains, the Rhine in this area was unattractive for river-crossing operations as the east bank was edged with high cliffs and backed by more hills and forests. Allied planners remembered the hellish battles in the neighboring Hürtgen Forest the previous autumn and wanted to avoid a recurrence of this bloody nightmare. As a result, Eisenhower’s plan anticipated that the US Army would continue its assault on German forces in the Eifel in order to close on the Rhine, but once the river was reached, the focus of operations would be on either side of the US First Army.

A pair of M4 medium tanks from Combat Command B, 2nd Armored Division, cross a treadway bridge over the Roer into the battered town of Julich on February 26 following several days of fighting during Operation Grenade. (NARA)

The first phase of the Anglo-American offensive began on February 8 with two operations aimed at closing on the Rhine in the northern sector.1 Operation Veritable was Montgomery’s effort to push the 21st Army Group through the Reichswald and into position on the west bank of the Rhine for a major river-crossing operation. Operation Grenade was a supporting effort by the US Ninth Army to finally clear the Roer River and especially its dams as a prelude to future operations along the Rhine. In late February, Eisenhower approved a First Army plan to assist Operation Grenade with a simultaneous crossing of the Roer on February 23 to protect the advance’s southern flank.

Operation Veritable proved more difficult than anticipated on account of the flooded terrain and stubborn German resistance. With the heaviest concentration of German forces opposing the Canadian and British forces, Operation Grenade made far better progress and on March 2, the US Ninth Army reached the Rhine at Neuss. General Simpson, the Ninth Army commander, pointed out to Eisenhower that nine of his 12 divisions were free to conduct a surprise crossing of the Rhine. Eisenhower deferred to “The Plan,” waiting for a crossing in Montgomery’s sector between Rheinberg and Emmerich. The First Canadian Army finally linked up with the US Ninth Army and cleared the area between the Maas and Rhine rivers by early March.

With the first phase of the Allied offensive complete, the US 12th Army Group commander, Gen. Omar Bradley received Eisenhower’s permission for the First Army to close on the Rhine. Operation Lumberjack began on March 1, 1945, with the aim of clearing the west bank of the Rhine from the Cologne area south, linking up with Patton’s Third Army on the Ahr River near Coblenz.