29

My old friend Ved: this week a large number of carvings were unearthed in the biscuit-colored beach off Half Moon Reef. All those elements one has come to recognize as central to the aborigine cosmos are here: the lost lôplôp, the horned lizard, the laughing parrot so needlessly decimated by Fogginius. Vulture and bee (both princes of the air) are here, as are the spirit of wind, water, and weather. Coral and quartz are represented as beautiful women, as is fire. Touch, moonbeam, and starlight are children; decay, ashes, sight, and foresight are all fanciful beings, part man, part beast.

In the center of an orbit warped by telluric upheaval, the Master and Mistress of Cosmic Things were found deeply buried and tenderly entwined. With the fingers of his right hand, he, even now, gently presses his beloved’s nipple; spurting milk, it will create the Caribbean Sea. Throbbing and thrashing in her fist, his sex is about to inseminate the waters.

Because of the significance of the find, the island is making ready to receive prominent cosmologists from the world over. I sincerely hope—despite the dubious intelligence that you are, as you say, “getting quite old, too old, my wife insists, for fantasy”—that you, beloved teacher and friend, will be among them.

The Clean Sweepers, torn asunder by patriotism and their hatred of the sensual world and its sexual determinisms, are hotly debating among themselves. There has been a renewed interest in the museum and its collections.

Today, when I returned, it thundered and squalled with schoolchildren. I had not seen it so animated in years. Protected by the newly installed electronic eye, the island Venus stood in all her luminous beauty—the light streaming through the rotunda’s glass dome was especially bright. I turned left into the west wing and, clearing a sweeping run of marble steps, passed through the hall that bristles with the gigantic skeleton of a whale. (It is said that at the time of the conquest, they swam the environs of the island in such numbers it was difficult for lesser vessels to navigate safely.)

There is a curiously tenacious story—perhaps you have heard it?—that the island was once peopled by a race of giants who fed upon whales just as you and I feed upon whiting. As if, with time, the whimsical pygmies of the conquest—living in baskets and chewing cigars—had become as big as their own cosmology, as gigantic as the harm done to them. A preposterously somber oil painting of the Old Fantasma, wearing a blood-splattered cloak and a ruff of sea silk, lords over this ordered boneyard.

A passing comment on the tyrant’s collar: the aborigine harvested the byssal filaments of a narrow shell genus Pinna, which once proliferated in the region. These threads were woven into a sumptuous cloth they used for bedding. The secret of Birdland’s own golden fleece, was lost when the last native weaver died refusing to reveal the sacred place where the Pinna were harvested. The supremely rare collar illumines a bitter face, umbrageous and cruel.

Of the silk, not a fragment remains. The collar—for a time displayed beneath a glass bell—succumbed, despite precautions, to the larva of a moth coincidentally named Argonautae by the island’s own celebrated lepidopterist (I believe you have met him): Professor Capricornes (now ninety!).

Back to the récit of my morning. Referring to a map hastily sketched in an acutely feminine hand in sepia ink on the back of a used envelope, I entered into a maze of rooms previously unknown to me, passed the laboratory of fossil vertebrates (a surprising amount of sawing and hammering came from within and the hallway was hazy with dust, so assiduously were the remains of extinct species being coaxed from their prisons of limestone and shell). Taking the stairs and turning left, I passed through the storage of mammals—a queer room of oiled shelvings and cabinets crowned with rows of skulls. Then down a corridor of specimens kept in alcohol—the soft shell-less bodies of volutes, conches, and cones for the most part—or so I was informed by their labels.

Finally, circuiting the dome of the amphitheater and ascending a stairwell that leads to a tower, I entered the room of marine invertebrates, a charming room painted an uncharacteristic butter yellow, and illumined by one graceful arched window overlooking the kindly trees of the botanical gardens. Here is a room packed like a cornucopia with wonderfully named shells: tulips and spindles, nanunculi and lilliputs, lyrias and music volutes, torrids and lion’s paws, combs of Venus, mice, ladders, turbans, olives, and apples! And here I found the rarest lion’s paw of all—Polly with her tangled hair, hazel eyes, and little round spectacles.

Polly had spent the morning painting a series of unique moon shells (she and Professor Cocles—Rojo, yes! He is still full of vim and vinegar!—are compiling a definitive work on the subject). She had rendered them in full color in relief with such conviction that I attempted to pick one up!

“You smell of ambergris,” I said to her, touching her neck with my lips and quoting Nuño Alfa y Omega’s poem: “my love, you smell of almonds.” We kissed for one long moment and Polly, who knows the poem now as well as I (in fact one cannot go anywhere on the island these days without hearing its verses, which have all been put to music), replied:

“Your fragrance is the fragrance of morning.”

Indeed, Phosphor’s poem, transmuted into the stuff of twentieth-century romance by the rhythms of a Birdlandstyle bolero, filtered up to us from the street below:

… of those mornings when

searching for shells I find treasure

a book of water written in an ink of salt.

And your taste is the taste of tempest

of those stormy hours when the wind, unbound,

tastes of foam; when the stars, unfixed,

taste of sleep; when the visible sea tastes of love.

You are all the seasons, all the hours

every kind of weather

all the minutes of fleeting time.

My protean dancer, my fish, my panther

You taste of water

and your taste is the taste of a dream

from which I awaken transformed.

Polly had acquired for me the key to the museum’s darkest collection—those objects used by the Inquisition to break the bones and the spirits of its enemies. I wanted to see the funnel that had served to pour quicklime down the poet’s throat. I wanted to hold it in my hand so that I could never forget such a thing had happened: that a poet had been silenced simply because he had been passionately in love. And I wanted to confront the obscene funnel armed with the knowledge that the poet had not been silenced after all; that his poem (discovered just a few steps from Polly’s laboratory) had not only survived—it was flourishing.

In fact, the funnel was forgotten. For as she proffered the key, Polly had, with a glance and an affectionate gesture, expressed her longing for me. And so within that room of scattered sunlight and sumptuous shells, we set about to participate in the ancient dance—I might say the one dance and the only dance that matters and that is so beautifully represented by both Phosphor’s poem and those aboriginal carvings of couplings so recently brought to light.

Ved, I know you will ask further precisions concerning the stone figures. My first impulse will be to say: Come! Come at once and see them for yourself! And while you are at it, come feast your eyes upon my beloved too; come witness our affection and be embraced by its festive warmth! We shall celebrate our amorous encounter next month. Come for the feast! Twelve sorts of oysters (Polly and I will have known one another twelve weeks), twelve sorts of scallops and clams, twelve sorts of mussels, champagne, and lime pie!

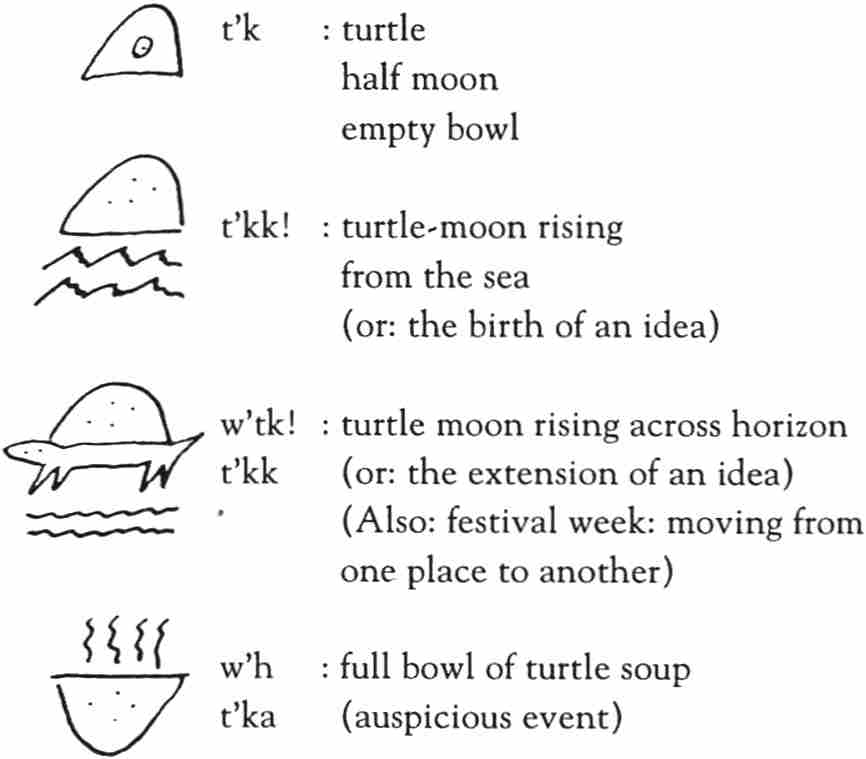

I have just viewed the figures myself—all mossy and caked with deposits of clay and sand (and the little egg-sacks of spiders and rootlets of ferns and the small bones of lizards … ). I cannot contain my excitement. For these are clearly elemental powers, those potent inventions that informed the aboriginal universe with a poetic intention. What is more, each has a text inscribed at its base: the aborigines, despite the historians’ insistence to the contrary, had a written language and a sumptuous alphabet that the prominent scholar Gertrude Hubble regards as a syllabary containing forty consonants (many of these are clicks), the vowel sounds implied, perhaps, by the number of hairs or horns or spots or stripes or teeth or eyes or petals or tongues appearing on letters for the most part in the shapes of creatures: snake, snail, starfish, etc. The text at the base of the spine of one great basaltic torso looks a little like this (I never was an artist!) and is read, according to Hubble, from top to bottom, left to right:

Rumor has it that Hubble has cracked the code, and we await her revelations breathlessly. (All the more reason for you to come!) Thus far she has, in private, divulged only this to me:

Dear friend! This morning I awoke laughing. I had been dreaming of days past and a thing you once said surfaced in my dream. You recall, I am certain, those conversations that so engaged us in the late seventies when, far away in Colorado, a brilliant (and heretical!) natural historian suggested (or rather, revealed) that the dinosaurs were fleet, smart, and colorful. “And not,” you said, “grey—as we had been taught—as though the great lizards were nothing more than the discarded plumbing of the Industrial Revolution!”

Last night, alone with my beloved on the black sands of Point Comfort Beds, I gazed upon the zodiacs peculiar to my island’s particular neck of the woods. And it seemed to me that forming distinctly above my head was the outline of a female figure, full-bodied and on her hands and knees. And that pulsing behind her, close upon the twin orbs of her bountiful posterior, kneeled a great beaked figure—an enigmatic lôplôp.…