9

Yahoo Clay’s banishment was postponed until the instant he would be fit to travel—although it would not be certain for some weeks that he would even survive. He was tended by Fantasma’s personal doctor, who was, as you know, no other than Phosphor’s hated stepfather, Fogginius.

Now so old as to be bent in two and nearly blind, Fogginius used his nose both for navigation and as a probe, rudely prodding people in the buttocks and at table ruining the perfect geometry of a rice pilaf or a gelatin pudding. When he peered into his stepson’s face for the first time in two decades, he thought he saw the cook and asked at once for milk soup. Informed of his mistake, and introduced to Nuño the inventor, Fogginius, his nose poking Phosphor’s navel, apologized to Nulo the impersonator.

Fogginius tended to Clay with a soup of slimes boiled twelve times in honey; with tincture of marshmallow and fumigations of texts written on veritable Egyptian papyrus in invisible ink; he blew air into Clay’s festering lungs through the windpipe of a whooping crane.

These were the sanest elements of the cure; Clay was also given a purse of wet sheep dung to wear on his stomach, and as he could barely move—so labored his breathing (and the man wept each time he had to swallow)—he complied with Fogginius’ demands and lay immobile and wheezing, the purse of dung burning like an infernal castigation.

Meanwhile, Señor Fantasma prepared for the necromantic voyage by ordering all the equipment required and outfitting the mules to Fogginius’ specifications. He had the cook prepare a compact and inedible bread made of popcorn and mud.

Phosphor concerned himself with the task of producing travelers’ spectacles for everyone, including his stepfather, who—as he could not tell the difference between a bird cage and a breadbox—was about to be totally incapacitated. Although they would spend many months together side by side, Fogginius would never recognize the stepson he had once so liberally thrashed.

Phosphor also saw to it that each traveler owned a sunshade for those instances when they would be continuing along the exposed coast or across the island’s notorious badlands. He also provided sandals, for many points of interest could not be reached by mule. (The paved and cobbled roads that now net the island, to the felicity of the curious tourist, date from the early part of the twentieth century.) Little Pulco proved to be a serious apprentice cobbler, and the task of sandal-making was left to him.

Because Clay’s recovery was tedious and protracted, Phosphor and little Pulco had plenty of time to accommodate themselves to their new environment. Pulco slept in the kitchen on a little pallet of fresh straw; for the first time in his life, Phosphor slept in a bed between clean sheets. They took their breakfast—of eggs and fruit and sugared rolls and fresh coffee and jams: of rose petals, of quinces, of peaches, of limes—in the great kitchen, which opened out on a sunny veranda smelling of freshly washed shirts and the hot bodies of roosting hens. However, despite the luxury of their surroundings, Clay’s battle with death permeated the entire house. Even the weather appeared to be affected.

During all the weeks of Clay’s convalescence, the sky was like lead. Once after urinating, Fogginius declared he had produced lava. Gazing in a mirror, little Pulco was surprised to see his face had not melted in the heat. The cook declared she felt as heavy as a plum boiled twelve times in sugar. Even when freshly bathed, they all attracted flies.

“We are creatures of lead,” Fogginius repeated more often than necessary, “and drunk on it.” And he held with both hands the hard, hollow bone that barely contained his reeling thoughts, and shuddered.

A few weeks after his mishap, Clay’s fever worsened. His breathing was so bad one could hear his lungs rattle throughout the Big House. That evening the cook dug up a mandrake in the kitchen garden. Headless, sexed like a man, it had two strange little arms and hairy legs. Although it squirmed in her hand, she brought it into the kitchen and with a sharp knife she severed the mandrake from its leaves. Although it continued to kick, she washed it well in water and vinegar and put it in a deep bottle with plenty of good pear brandy. For an hour it floated at the top, but then it dropped and hung thereafter suspended in the middle, immobile and silent. (When the museum put up various miscellanea for auction last spring, I was tempted to purchase it, but didn’t.)

For weeks, only the mandrake and the moon floated; everything else was weighted down. Phosphor’s clubfoot pained him and he began to look upon the imminent voyage with trepidation. However, Clay, taking bouillon daily and even a poached egg, was still too ill to travel.

One afternoon, as little Pulco sat in the kitchen poking holes into leather, a dragonfly sailed in through the open door to lay her eggs in a dish of water. She was immense, gorgeous, green and yellow to the tip of her tail, which was a metallic blue. This tail was pronged, a claw or hook, and so bowed in sexual tension that Pulco feared it would snap in two. As her eggs tumbled into the dish, Pulco clasped his hands and his heart hammered.

Sometimes in the early evening, as Phosphor ground the lenses of the travelers’ spectacles (and he had already perfected a folding tripod that could be screwed to the base of his black box), Pulco sat in the garden shed. It smelled of baking, of the wings and bodies of all the things which, trapped there, were gradually reduced to dust.

In the shed, Pulco played with the tubers and bulbs—many imported from Holland or Brazil, or even the Orient in pine crates stuffed with straw. Or he wandered Fantasma’s overgrown gardens, which were always empty. Sometimes he sat among the ripening pineapples and listened to the gardener pumping water from the deepest well—the only well not dry—to soak the roots of the alligator pears, the mangos, zopotillas, and the blazing pepper plants. The sand paths, stiff with salt, glistened.

When the paths were damp from waterings, and as the water evaporated, butterflies settled. In those days in Birdland, there were so many butterflies entire trees were often hidden by their tremulous wings. The coastal hills blazed scarlet, bronze, or blue during their seasons of copulation.

Once, still as a stone, Pulco watched as an Adonis sat in the path and collected the cool air under its wings. When the Adonis settles, it closes its wings and vanishes. Only when it flies, zigzagging in the air, do its bright violet wings catch the eye. In this way it is very like Pulco; crouching in the shadows he melts away, but when he moves he is highly visible. Lurching first this way, then that, he too zigs and zags.

Often in the late morning when Pulco had completed his tasks, he explored the Big House, its tiled corridors with windows opening onto fragrant, if seedy, courtyards. Or he played in the kitchen with toys once belonging to the cook’s daughter, little Tina, who died extravagantly as she played Hide and Seek among the bananas—beheaded, accidentally, by a harvester’s machete. The games Pulco played were circumscribed by his own imperfect infancy: he imagined things too precisely, he felt things too acutely, and his mind had a tendency to move in ruts. If the game veered into the unexpected, or took up a dark course, Pulco became frightened and sometimes he shrieked.

It was Pulco’s conviction that the world was ruled by Six Persons who had once climbed out of a hole. In his games he found this hole, more nidus than abyss, and the Six rewarded him with freedom from tasks and a family. Pulco described the Six so precisely that the cook, overhearing his childish prattle, would see them too—huddled together in the deep shadows, forming a sinister circle—Africans and Eskimos and Indians—like the ones on Señor Fantasma’s faience dishes. She can see the Choctaw warrior dressed in nothing but a garland of clotted scalps, the Chinaman just as Marco Polo described him—sword in hand—and suddenly little Pulco is shrieking, his shrieks tear the air like a flock of startled crows.

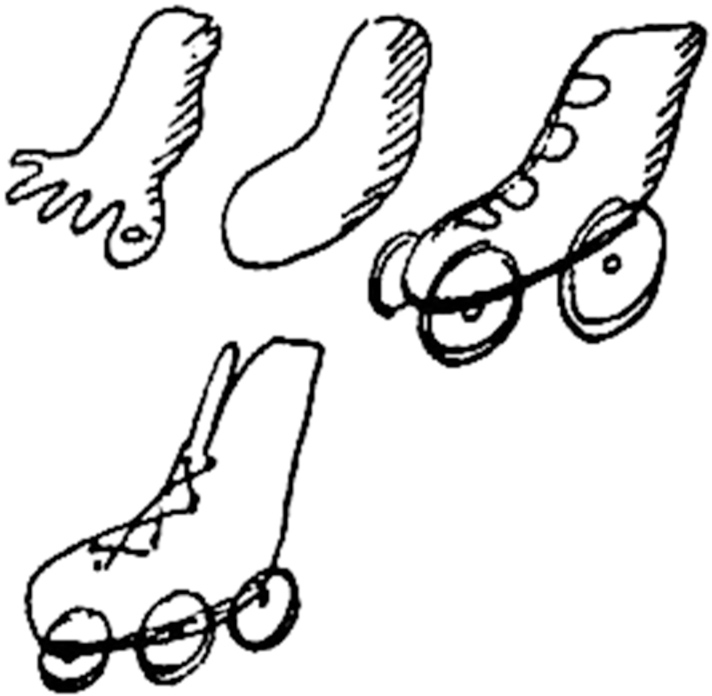

Whenever little Pulco begins to shriek, the cook sinks to her knees and holds him until, feeling better, he can tell her another secret dream: one day to make for his master, Nuño Alfa y Omega, a shoe with wheels.

Pulco draws a picture so that the cook can see just how these shoes should be. He next draws his master’s feet—one perfect, the other shaped like a hammer. Pulco explains that it cannot be cut off; it is as much a part of his master as the eyes burning in his skull, his beating heart, his thinking brain:

Near the end of August, Yahoo Clay rose from his bed. It was Phosphor’s conviction that it was not, as Fogginius insisted, the action of the waning moon, nor the dung upon his heart, nor the soup of slimes he had ingested every day for sixty days, but rather that Clay could no longer stomach Fogginius.

As he had tottered above the pit of death, Clay had endured the circuitous legend of Saint Sousmyos, had, against his will, considered the progressive and retrograde motions of the stars, the nature of the souls of animals, the divinity of the number six. He had heard named and counted all the bones of the body. He had considered the fact—gruesome to Fogginius—that all the magical paraphernalia of Simon Magus lies rotting at the bottom of the sea; Fogginius could not recall which sea. When one late afternoon Fogginius proposed readings from the Latin glossary of Ansileubus “to entertain and occupy his patient’s mind,” Clay, bleating the sound a sheep makes just as its throat is slit, heaved himself up and away. Thereafter, he could not speak—for weeks, that is—but only bleat. This did not interfere with his function; Señor Fantasma needed the thug for a shield from dangers less real than imaginary. Shield and shadow, Clay’s voice had always been superfluous.

Ved—the compilation of all this material has, thus far, taken up the better part of the winter. Profoundly, inconsolably alone, a man without a love (and so, as you once said, without a home), I decided to re-create a world that is—save for threads and tatters, “feathers and fables”—forever lost. My passion for the island’s early history decided me to devote myself to one extraordinary moment (and person: Nuño Alfa y Omega)—and this, dear Ved, for you.

If at the outset I was, in particular, intrigued by Phosphor’s extreme precocity and the beauty of his images on metal and glass, the plight of four lonely men (and one innocent child) on a pilgrimage of sorts could not help but fire my imagination. Sometime during the winter—that glorious season of intense verdure and daily rains—it came to me that love offers the only intimation of eternity. That it is the loveless men, those incapable of profoundly feeling, who scrabble after fame and power. Because their life is, in fact, the other face of death.

These reflections bring me back to Swift’s curiously loveless life; after all, he kept his Stella in a box as though she too were far too curious or monstrous to be “let loose”! I have been rereading what Alicia Ombos calls his spy-glass poems: those poems in which the suitor explores his absent lady’s chambers, putting his nose into the very things that cause his virility to recoil in horror. It is clear that for Swift, femaleness is the lie that conceals the bitter bones of truth. He cannot forgive the flesh because it dies; he cannot forgive woman the transitory physicality that defines, determines (and damns) him, too. In these poems, the distinctions between the real and the false, corruption and health, sex and death are abandoned and the rifts between them, in Ombos’s words, lizard in all directions until the landscapes of these burgled rooms swell and crack as though in the throes of intense seismic upheaval.

Returning at midnight, Ombos continues, that exemplary hour of revelation, Corinna pulls off her hair and plucks out her eye. Her macabre striptease reveals that she is nothing more than a species of upholstered coffin: tacks, tassels, and padding removed, all that remains is an eager abyss (eager because once abed the hag lies tormented by dreams of love!).

For Swift, Time is female and it is female flesh that, above all things, epitomizes Swift’s own terror of dissolution. Perhaps the cyclical cacophony that tortured him throughout his life (he was a victim of Ménière’s disease) translated into an acute perception of the particulating world. Was Swift’s wounded inner ear particularly sensitive to the sound of Her minuscule but incessant teeth? In any case, the passage of Time, above all in Swift’s poems, is accelerated to a vertiginous degree; like particles in an atomic cannon, matter fractures and dissolves before our eyes:

… And this is fair Diana’s Case;

For, all Astrologers maintain

Each Night a Bit drops off her Face,

while Mortals say she’s in her Wain.

—“The Progress of Beauty”

Writes Ombos: I would suggest that Swift distrusts both voids—fore and aft (mouth and anus)—as acutely as he distrusts the “visions” (or “humors,” or the guts) in between; that his imagination pierces to deflate; that the eye of Swift’s needle is as sharp as its tip; that the vision is a species of sprawling body that will not be contained: the body as landscape, quicksand, as bog; the world an ogress riddled with orifices, littered with dung (in which Gulliver/Swift so often finds himself “in the middle up to my knees”).

But I fear these reflections have little place here in this history that reads more like a fable! I can hear your stern criticism: Don’t burden your book with IDEAS!!!

Back to the tale.…